?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The theorised reorganisation of global value chains (GVCs) during crises periods and the European Union advocating for a relaunch of manufacturing activities in favour of jobs creation bring about the crucial question whether a relaunch of manufacturing employment via backshoring in Europe takes place with an intensity large enough to be captured by aggregate statistics. Defining backshoring as a process according to which production of a region uses again a greater share of domestic relative to foreign inputs, the paper operationalises the definition using suitable indicators at the NUTS-2 level and tests the relationship between backshoring and regional manufacturing employment dynamics.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the early 1990s, global value chains (GVCs) drove dramatic expansions in trade, productivity and economic growth, advantaging countries from the international division of labour, whereby activities that used to be undertaken in a single location were dispersed among many countries (e.g., Gereffi et al., Citation2001). The gains were a clear increase in efficiency and economies of scale in the execution of single tasks. For more than a decade, international trade in intermediate goods increasingly became the norm for advanced countries, European countries being not an exception in this respect (Brenton et al., Citation2022).

With the 2008 crisis, some doubts on the efficiency of this international mode of production process started to emerge (Accetturo & Giunta, Citation2016 Baldwin, Citation2009a;). The ‘Great Trade Collapse’ was interpreted as the result of an integrated, interdependent and specialised world, where the decrease in the final goods in the US propagated very quickly, in a domino effect, via a decrease in all intermediate goods produced all over the world (Altomonte et al., Citation2012; Cattaneo & Staritz, Citation2010). As Baldwin claimed, ‘the collapse was caused by the sudden, recession-induced postponement of purchases, especially of durable consumer and investment goods (and their parts and components)’ (Baldwin, Citation2009b, p. 1).

World trade in manufacturing fell by about 30% between the first half of 2008 and the first half of 2009 (World Trade Organization (WTO), 2009). The fall in trade during the crisis was also quite homogeneous across all countries: more than 90% of the OECD countries simultaneously exhibited a decline in exports and imports exceeding 10% (Araujo & Oliveira Martins, Citation2009). European Union (EU) countries were severely affected, with marked declines in both industrial production and merchandise trade.

Since the global downturn in 2008, possible reshoring of production from emerging countries started to be a valuable option for advanced countries, and a reduced dependence on foreign production was considered a way out of productivity and employment stagnation in the manufacturing industry. In fact, this process came at a time when the debate on the risks of an international ‘trade in task’ production method was associated to the unpleasant consequences of the deindustrialisation trends in developed countries. The decrease of employment in Europe was attributed to the loss of manufacturing, a situation that pushed the EU to call for ‘a strong, competitive and diversified industrial manufacturing value chain for the EU’s competitiveness and job-creation potential’ (EC, Citation2010, p. 3). The famous EU ‘Manufacturing Imperative’ was launched by the EU in those years to avoid the loss of long-term productivity growth and living standards (Capello & Cerisola, Citation2023b; Ciffolilli & Muscio, Citation2018; European Commission, Citation2014). In the same period, a debate emerged in the US claiming that the production in the US, with an increasingly flexible workforce and a resilient corporate sector, was becoming more attractive as a place to manufacture many goods consumed on that continent. The Boston Consulting Group calculated that around the 2015 manufacturing in some parts of the US would have become just as economical as manufacturing in China, where wage increases scaled back the US–China wage differences (Sirkin et al., Citation2011). A ‘US manufacturing renaissance’ was advocated mainly as a lever for US job creations (Sirkin et al., Citation2012).

The COVID-19 pandemic relaunched both the backshoring and the reindustrialisation debates (Barbieri et al., Citation2020). On the one hand, the health crisis highlighted the fragility and vulnerability of the international organisation of production. Severe supply security issues have emerged, due to various key production centres that entered lockdown (e.g., China), generating a shortage of supplies of intermediate and final products throughout the world. This was especially clear in relation to the supply of health-related goods, like personal protection equipment (e.g., face masks) and such as-saving mechanical ventilators (Gereffi, Citation2020). Such risks called again for backshoring processes.

On the other hand, the EU officially claimed ‘the need to reverse the declining role of industry for the twenty-first century, so to relaunch productivity’ (European Commission, Citation2012, p. 1). In fact, the low GVA growth capacity, the productivity gap of Europe and the drawbacks mentioned above pushed policymakers towards the idea that Europe needs to reverse the declining role of industry within its boundaries, avoiding competing on low-price and low-quality products, but strengthening instead an industrial competitiveness based on a high technological level to enable the transition to a low-carbon and resource-efficient economy (European Commission, Citation2012, Citation2014, Citation2021, Citation2022; Capello & Cerisola, Citation2023a).

Reshoring in both its forms of nearshoring (from developing to European countries) and of backshoring (bringing back to the area that was previously producing the goods) seems to be a strategy envisaged by the EU to put in place its reindustrialisation process (De Backer et al., Citation2016; European Commission Citation2021). Despite reshoring being widely assumed to be performance-enhancing for the firm and beneficial for the country (Karatzas et al., Citation2022), the empirical investigation of the phenomenon and of its real effects is still quite limited.

Case studies exist at the firm level indicating the motivations for large multinationals to relocate their plants in the home countries (Boffelli & Johansson, Citation2020; Di Mauro et al., Citation2018; Johansson et al., Citation2019; Johansson & Olhager, Citation2018; Karatzas et al., Citation2022; Savi, Citation2019), and surveys have also been launched, measuring the phenomenon and its effects at firm level (Kinkel & Maloca, Citation2009). What is instead still largely missing is an aggregate macroeconomic approach, able to grasp the overall entity of the phenomenon, and of its effects, with some exceptions at the theoretical level (Krenz et al., Citation2021). In order to reason at the macroeconomic level, backshoring has to be interpreted as a process according to which production of a country (or region) uses again a greater share of domestic relative to foreign inputs. This phenomenon can be the result of two effects. In fact, it can be either the outcome of multinationals bringing back to their home countries their production functions (what is called in the business international literature a backshoring) or of firms located in the home country producing intermediate goods that were previously imported. At the aggregate level, the effect is the one of stimulating local production in the same industries and/or in related ones, via input–output relationships. In order to be sure that under these conditions a reshoring process takes place, this process has to take place in areas that have gone through a period of de-industrialisation and are now re-industrialising.

While attempts to measure a reshoring (or backshoring) process at aggregate level exist (e.g., Fuster et al., Citation2023; Gao et al., Citation2022; Krenz et al., Citation2021), little is known about the aggregate effects that it generates. Can we already speak about a relaunch of manufacturing employment by looking at aggregate data via a backshoring, or has this phenomenon still to be treated in an anecdotal way, with macroeconomic effects on home countries still to come? As per our knowledge, evidence of the aggregate backshoring effects does not exist. The importance of such an analysis lies in different aspects. Backshoring does not take place with the same intensity all over the country. Instead, a higher intensity would expect to be present in traditional manufacturing regions, where an industrial vocation existed, and therefore where the relaunch of manufacturing activities could more easily occur. Moreover, a backshoring measure would allow to highlight the territorial outcome arising from such a trend in trade. In particular, at the local level one would hope for a reinforcement of traditional industrial knowledge that could reverse the impoverishment of the knowledge flow on the territory, or even the erosion of territorial know-how (Martinez-Mora & Merino, Citation2014) and avoid a catastrophic displacement of entire economic filières caused by GVCs (Camagni, Citation2016). In this paper, we adopt the term ‘backshoring’ to indicate a process according to which the production of a country (or region) uses again a greater share of domestic relative to foreign inputs.

The territorial trends and impacts of backshoring in Europe are largely unknown. This paper aims to fill such a gap. It looks at two main issues that are particularly interesting in this respect, namely the capacity of backshoring to relaunch manufacturing employment and, in particular, the ability to restart industrial vocations in traditionally manufacturing regions.

The paper reports what the literature claims so far on GVCs’ restructuring’s intensity, motivations, and effects (section 2), presents the conceptual measure of a regional (subnational, aggregate) backshoring (section 3), the model specification for the impact of backshoring on manufacturing employment dynamics (section 4), the results obtained for European NUTS-2 regions (section 5), and some concluding remarks (section 6).

2. RESHORING: DEFINITION, EFFECTS AND MEASUREMENT ISSUES

The 2008 crisis and the ‘Great Trade Collapse’ that followed opened a vast debate on the restructuring of GVCs. Forms of restructuring are rather diverse, from reshoring, in its form of near and back-shoring, to geographical, productive (Álvareza et al., Citation2023; Thi Thu Huong & Park, Citation2021) and functional (Coveri et al., Citation2022) diversification of GVCs. In this study, the interest lies on reshoring, being the crucial aim of the study to investigate whether a relaunch of manufacturing employment via backshoring in Europe takes place with an intensity large enough to be captured by aggregate statistics.

A vast debate took place especially on the reshoring phenomenon, defined by the international business literature as ‘moving manufacturing back to the country of its parent company’ (Ellram, Citation2013, p. 3), or even in a more generic way as a change of location with respect to previous offshore countries (Fratocchi et al., Citation2014). The first definition refers to backshoring, defined in the literature as the ‘re-concentration of parts of production from own foreign locations as well as from foreign suppliers to the domestic production site of the company’ (Kinkel & Maloca, Citation2009, p. 155), or the relocation of parts of production back to the home domestic country of the company (Holz, Citation2009). The second definition, instead, deals with near-shoring, defined as the decision to relocate previously offshored activities not necessarily back to the home country of the company, but rather to a neighbouring country of the home country (De Backer et al., Citation2016).

Reshoring is the outcome of several ‘megatrends’ reshaping international production and trade (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Citation2020). At the firm’s level, the relocation comes out both as a deliberate strategy, and/or as a reaction to the offshoring failure (Foerstl et al., Citation2016). When learning opportunities, efficiency and flexibility are deteriorating, firms generally start evaluating the option of bringing back operations to their home country or region in order for instance to increase control (Pedroletti & Ciabuschi, Citation2023). Miscalculation and/or underestimation of full costs of offshoring, making the choice of offshoring unprofitable, quality and brand image, country factor costs, reconfiguration and restructured costs, production automation, responsiveness and resource efficiency, risk management, and dependability and institutional-driven agenda to backshore manufacturing have been identified as the main causes for firms’ decision to reshore (Srai & Ane, Citation2016).

At the aggregate level, reasons for reshoring have been identified in national governments increasingly engaged with industrial GVC policies at the national level (Pegoraro et al., Citation2022), protectionist initiatives or actions in trade and investment undertaken by countries (UNCTAD, Citation2020; Pedroletti & Ciabuschi, Citation2023).Footnote1 But also changing cost structure in emerging countries, growing digitalisation and robotisation of manufacturing countries, efficiency in co-location of research and development (R&D) and production activities, a balance between cost savings and risk dispersion, and potential threats to intellectual property are by far the most important reasons for reshoring as a deliberate strategy (De Backer et al., Citation2016). The effects of pro-reshoring policies are today visible in most developed countries (Elia et al., Citation2021). Moreover, despite the constant increase in Chinese labour productivity, this is not enough to compensate for the increase in wages in that country, a trend that erodes over time the competitive advantage of the large exporting country of intermediate goods towards the US (Sirkin et al., Citation2011).

While the debate on reshoring, in all its forms, is at least a decade old (Dachs et al., Citation2019; Pedroletti & Ciabuschi, Citation2023), evidence of its existence is still rather mixed, making it very difficult to assess its real presence, its magnitude, and its effects. There is therefore a need to carefully investigate the intensity of the phenomenon so to move to the measurement of consequences of reshoring on firms’, regions’ and countries’ performance.

Different approaches to the measurement of reshoring exist in the literature. The most diffused one is at the firm level, through case studies or firms’ surveys. The case study approach deals with single multinationals’ locational behaviours, through the interpretation of their relocation strategies. Famous case studies are Apple and Samsung that decided to move production out of China and expand in Vietnam and, most recently, India, to diversify supply chains away from China (Kearney, Citation2023). Firm-level surveys refer to large questionnaires collecting reshoring initiatives, and building databases on the intensity and reasons for reshoring. Intriguing results have emerged in this last approach to backshoring. In the period between 2010 and 2012, about 2% of all German companies have backshored their activities, while the number of German companies that offshore activities is constantly declining (Kinkel, Citation2014). In addition, a survey at the European level has shown that around 4% of firms in the sample have moved back their activities (De Backer et al., Citation2016). The US Reshoring Initiative (Citation2020) organisation found that jobs created through reshoring in 2020 totalled over 109,000. Further, the report noted a record number of companies (more than 1400) reporting reshoring in the US (Dikler, Citation2021).

If the firm’s approach has the advantage of analysing the phenomenon from its source, it necessarily lies on limited survey analyses and anecdotal evidence, lacking the capacity to give a sense of generalisability of the phenomenon. Two complementary ways of observing reshoring exist at the aggregate level: the production approach and the macroeconomic approach. The production approach refers to an analysis of all registered multinationals and their location over time. Such information comes from individual firm data from ORBIS, a database which contains detailed balance-sheet information on millions of companies, combined with information on the ownership and group structure. Once used within an econometric analysis, such information provides the effects of relocation of multinationals in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) and employment growth of the host and home countries/regions (Amador et al., Citation2015; Ascani et al., Citation2020; Bettarelli & Resmini, Citation2022). De Backer et al. (Citation2016) find evidence that fixed assets and employment in multinational enterprises headquarters and affiliates located in the home country grow relatively faster than that of other multinational enterprises affiliates and interprets such result as an indication of reshoring.

The second approach is the macroeconomic, aggregate one, applied also in this study. In this case, the focus is on macroeconomic variables. A ‘reshoring index’ is proposed by Kearney (Citation2020). It is calculated as the ratio of US manufacturing gross output to import from 14 Asian countries. In fact, it has increased constantly over time since 2016, suggesting, according to the author, that US companies chose to source more goods domestically. While being the first attempt, it represents a very simple way of measuring the phenomenon, paying no attention to other sources rather than reshoring that could change the ratio, like an increase of the US economy, increasing the numerator and signalling a false reshoring situation.

A similar reasoning is applied in Fuster et al. (Citation2023). In this study reshoring is identified as the (negative) change in the ratio between the value of imported inputs and a country’s overall value added (VA). This index suffers of a similar limitation with respect to Kearney’s (Citation2020) one, since the variation in the index can be associated to a change in the country’s overall VA, keeping the value of imported inputs constant, a situation that has little to do with reshoring.

Another attempt to measure reshoring at aggregate level is proposed by Marin (Citation2018), who uses the ratio of imported intermediates from low-wage countries to total intermediates. When the ratio of a country (or a region) decreases over time, it is interpreted as evidence of reshoring, with the obvious limit that the decrease can be the result of a general crisis of the national (or local) economy, rather than of reshoring.

More recently, Krenz and Strulik (Citation2021) propose a more sophisticated index of reshoring intensity. They measure reshoring as the increase over time of the ratio between domestic value added (DVA) and foreign value added (FVA) content of exports in a country c, namely:

(1)

(1) This index states the intensity by which domestic inputs increased in the period relative to foreign inputs, putting to zero situations when foreign and domestic inputs simultaneously increase or decline, and controlling for production declines and increases over time, all situations that could wrongly be attributed to reshoring. This index has the advantage of measuring a shift in the share of domestic relative to foreign inputs, lacking however the condition that this shift takes place in the country that previously offshored production.

Another useful proposal of an aggregate measurement of GVCs’ restructuring comes from Gao et al. (Citation2022) who identify offshoring (production relocated from the home economy to the host one), reshoring (production relocated from the host economy back to the home economy), and re-offshoring (production relocated from the home economy to a third economy). For each, they identify an index for each of the phenomena, using inter-country input–output tables, as in Krenz and Strulik (Citation2021). Interestingly, Gao et al. (Citation2022) separate out two distinct situations for which foreign inputs may decrease in a local economy. The first situation is due to a substitution between different inputs in the local production; and the second is the spatial change of the suppliers of a specific input, which is the true reshoring phenomenon when the choice is in favour of an input producer that previously offshored.

For this second phenomenon, a specific index, called reshoring index , is defined as ‘the production of an industry relocated out from the host economy (where the offshoring relocates in during the benchmark period) exceeds the production relocated into the home country’ (Gao et al., Citation2022, p. 192), and calculated as the relocated intermediate production of industry i (in economy r) that is caused by the changes of spatial supply-shares in the intermediates used by industry j (in economy s) over time, namely:

(2)

(2) where

is the foreign value added produced in industry i for region r used by industry j (in economy s) at time t or t – 1, while

represents the global (total) foreign value added produced. If this index is positive (negative) it implies that changes in intermediates used by industry j (in economy s) relocate the intermediate production of industry i into (out from) economy r. This index interestingly interprets reshoring as the changes of spatial supply-shares in intermediate goods over time.

If literature exists on how to measure backshoring at aggregate level and its trend, little is known about the macroeconomic consequences of such phenomenon, especially at the regional (subnational) level.

This is not a trivial issue. It is linked to the reindustrialisation strategy that the EU advocates in order to relaunch jobs and productivity in Europe. The regional dimension is rather a rich addition to the analysis, in that it highlights how regions with different histories and traditions in manufacturing can pro - or re-act to a backshoring process. If this is the case, the spatial heterogeneity of backshoring can also lead to suggest that ‘one size fits all’ backshoring strategy to relaunch manufacturing employment in all regions may not be the most suitable to achieve the envisaged targets. To this end, the paper investigates the backshoring effects on employment, distinguishing between historically manufacturing regions, emerging manufacturing regions, and non-manufacturing areas in Europe.

Moreover, the analysis goes in depth into the exploration of the effects of backshoring in different local labour markets, distinguished according to different functional vocations. A region characterised by a low-skilled labour market will easily register increases in blue collars with respect to regions with a high-skilled labour market, where high-skilled jobs will be more easily created.

One of the main steps of the paper is to identify the way to measure regional backshoring (section 3), so as to estimate its impact on manufacturing employment growth in traditionally manufacturing regions compared with emerging manufacturing ones (section 4).

3. BACKSHORING: AN OPERATIONAL DEFINITION AND ITS MEASUREMENT

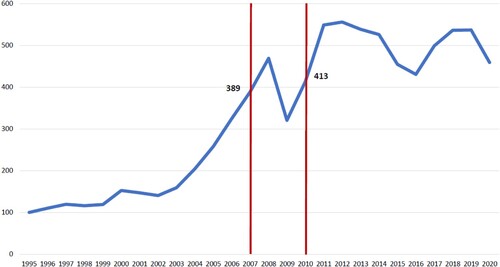

In this study, backshoring is intended as a process according to which production in a region uses again a greater share of internal inputs. In order to identify a situation like this one, we first identify regions that register a decrease in their dependence on GVCs, through a decrease in manufacturing FVA of intermediate inputs over time. Over the period of crisis (2007–10), in the EU28 FVA in exports clearly shows a contraction in 2009 (), signalling the existence of the Great Trade Collapse. After that, there was a gradual recovery, although past growth rates were never achieved again.

Figure 1. Trends in manufacturing foreign value added (FVA) in exports in the EU28 (1995 = 100).

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the trade in value added (VA) matrices provided by the EUREGIO database (Thissen et al., Citation2018).

Reduced dependence is in this work operationalised at regional level by building a dummy variable as follows:

(3)

(3) where FVA is the value added of imported intermediate goods used for exports of a generic region r, and 07 and 10 indicate, respectively, 2007 and 2010. FVA is obtained from the trade in value added matrices following Timmer et al.’s (2013, 2014) method explained in Appendix 1 in the supplemental data online.

This single indicator is not enough to capture backshoring. A process of reduced dependence after an offshoring period could in fact also be the result of a decline in production, without a move of production activities back home. In order to exclude such situation, we add an additional indicator that measures a reindustrialisation process, that is, a process in which the share of manufacturing of the region has declined before the decrease in FVA and then has increased again, in line with the literature that claims ‘decreasing offshoring can be a misleading indicator of reshoring since it takes not into account that foreign input shares in VA could decline due to a decline in production without a move of production activities back home’ (Krenz et al., Citation2021, p. 10). This aspect also controls for the fact that the decrease in foreign intermediate goods is not associated to a process of crisis in manufacturing.

Operationally, reindustrialisation is measured as an increase in the share of local manufacturing VA in the post-crisis period with respect to a decreasing manufacturing share in the pre-crisis period. For this purpose, a reindustrialisation index is built as a dummy variable equal to 1 if the change in the share of manufacturing VA over total in the (post-crisis, 2013–17) period is positive and the change in the share of manufacturing VA over total in the (pre-crisis, 2000–07) period is negative, that is:Footnote2

(4)

(4) where VA represents the value added, m is the manufacturing industry, r is the generic region, and the numbers represent the years. In particular, reindustrialisation occurs when there is an increase in the second (post-crisis) period with respect to a decreasing first (pre-crisis) period.Footnote3 For this index, the share, rather than the absolute value, guarantees that the price effects are controlled for, while the choice of the VA at current prices allows to take quality increases into account, which are instead mostly eliminated by a deflating process (Aghion et al., Citation2019; Camagni et al., Citation2022; Camagni, Citation2024). It would be in fact highly debatable to exclude from the measurement of a ‘reindustrialisation’ process regions that are able to sell their products at increasing prices, acquiring market shares.Footnote4

With these reflections in mind, backshoring is defined as a dummy variable assuming a value of 1 when both reduced dependence and reindustrialisation variables assume a value of 1, that is, when:

(5)

(5)

shows how the different periods concur to such operational definition.

This situation occurs when the imports of foreign intermediate goods decrease and are substituted with local production. The latter is guaranteed by an increase in the share of manufacturing VA. Being the index built at aggregate industrial level (manufacturing), the increase in the share of manufacturing can take place in an industry which is not the one where FVA of intermediate inputs decreases. This is not a limit since at the aggregate level it is relevant to consider all the effects of a reduced dependence on GVCs, even those ones involving input–output interdependencies within the manufacturing sector.

Given the short term in which reduced dependence and reindustrialisation are measured, it is likely that some input substitution takes place in sectors related to the one that reduced dependency, since this is where manufacturing knowledge exists, in line with the related variety concept (Boschma et al., Citation2012).

A crucial aspect is whether backshoring takes place especially in dynamic manufacturing areas, that is, areas characterised by an increase in manufacturing specialisation, as the phenomenon can be expected to be more effective in generating an impact on the local labour market. Within such regions, an additional important distinction is between those that were originally specialised in manufacturing and those that were not. The former are, theoretically, those where industrial vocations existed and can be labelled ‘traditionally manufacturing backshoring regions’. The latter are ‘emerging manufacturing backshoring regions’.

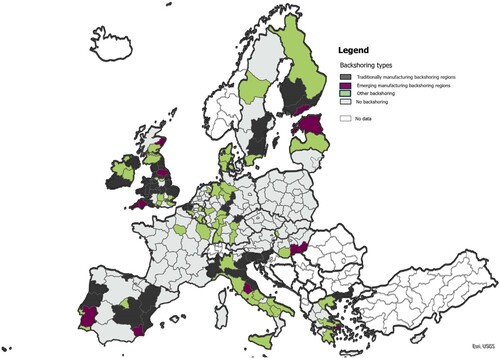

presents the backshoring regions, identified on the basis of equation (5) applied to NUTS-2 regions in Europe, distinguished among the different regional typologies.Footnote5 The traditionally manufacturing backshoring regions are a phenomenon of Western countries, spread around, clearly reflecting the highly specialised small and medium sized manufacturing firms’ regions in Italy (the North-Eastern and Central regions along the Adriatic coast), the Eastern part of Spain, part of the UK and Ireland. The ‘emerging manufacturing backshoring regions’ are scattered around with no particular national pattern, in both Western and Eastern countries.

Finally, we are also interested in understanding whether jobs’ reinstatement takes place in particular types of labour markets, that is, in generating specific occupational jobs. This aspect is grasped through the identification of different effects of backshoring on employment in different local labour markets, distinguished according to their functional specialisation.

Our research question is therefore whether backshoring regions have gained advantage in terms of manufacturing employment growth. In particular:

Does backshoring favour manufacturing employment growth in the European regions?

Does backshoring relaunch employment in dynamic manufacturing areas, so to revitalise industrial vocations?

Does backshoring relaunch employment in local labour markets characterised by specific functional specialisations?

4. BACKSHORING AND MANUFACTURING EMPLOYMENT DYNAMICS: MODEL AND DATA

4.1. The model specification

In order to explore the role of backshoring in the dynamics of manufacturing employment in Europe, we take advantage of a two-period pooled ordinary least squares (OLS) model, run on the European NUTS-2 regions, which are our units of analysis, as follows:

(6)

(6)

where emp man growthr(t,t+3) is the dependent variable and is computed as the regional (r) compound growth rate of the employment in manufacturing in two periods: 2013–16 and 2016–19.Footnote6 Backsh represents the backshoring variable built as in equation (5). Given that the construction of this variable requires comparing different periods (), the variable is time invariant. Since with the backshoring phenomenon we want to capture a structural (long-term) trend, this time invariant aspect does not invalidate our analysis. Time is a dummy variable equal to 1 in the first period; it is included to control for time fixed effects, and it is interacted with backshoring to be able to interpret its marginal effects in the two different periods considered. X represents a set of control variables, that enter the model in their value at the beginning of the growth period (t). In particular, the manufacturing employment dynamics depends on:

the level of education of the labour force, which influences quantity and quality of new jobs, captured via the share of tertiary educated population (Mackay, Citation2006);

the stage of development of the region, which explains the creation of jobs opportunities, measured through GDP per capita (Zanin & Calabrese, Citation2017);

the level of specialisation in manufacturing, influencing labour market through localisation economies, calculated as the share of manufacturing VA over total VA (Eriksson et al., Citation2008);

the settlement structure of the region, influencing through agglomeration economies the dynamics of the labour market, and measured through a dummy variable equal to 1 if the region includes at least one metropolitan region, as identified by the European Commission (Capello & Lenzi, Citation2013);Footnote7 and

the functional structure of the region, measured as either high-level functions, calculated as the share of International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO)-1 employees in the region, or low-level functions represented by the share of ISCO8 employees, and meant as a measure of production-level functional specialisation (Piva & Vivarelli, Citation2005; Quatraro, Citation2010).

Regional (NUTS-1) fixed effects are also included, and robust standard errors are clustered by NUTS-1 region.

The basic model of equation (6) is then adjusted to assess if there is in fact a relaunching of traditional industrial know-how and vocations in manufacturing regions in Europe. This objective is pursued by estimating the effects of backshoring on manufacturing employment for regions with different initial degree of manufacturing specialisation, increasing over time. Two groups of regions are highlighted in this respect. Traditionally manufacturing backshoring regions are identified as those specialised in manufacturing in 2000 and further increasing their specialisation over the 2000–17 period, while emerging manufacturing backshoring regions are devised as those non-specialised in manufacturing in 2000, but increasing their specialisation over the 2000–17 period.Footnote8

The analyses are carried out through a pooled OLS, since a panel fixed effects is not feasible, due to the time invariant nature of our variable of interest.Footnote9 The regional fixed effects enter the model at the NUTS-1 level to avoid perfect collinearity between the variable of interest (time invariant and identified at the NUTS-2 level) and NUTS-2-level fixed effects.

Finally, in the last step of the analysis, the specifications above are altered to accommodate the interactions between (different types of) backshoring regions and high-level/production functions, to shed some light on the type of occupations that are favoured by backshoring of high - or low-level activities.Footnote10 This is indirectly understood by speculating on the fact that a region characterised by a low-skilled labour market will easily be more inclined to generate new blue collars with respect to regions with a high-skilled labour market, where high-skilled jobs will be more easily created.Footnote11

A thorough description of the data and their sources is now reported.

4.2. The data

NUTS-2 level data used for the operational identification of the different types of backshoring regions and for the dependent and control variables explained above, are presented in , together with their sources and the related reference periods. Related descriptive statistics are reported in Appendix 2 in the supplemental data online.

Table 1. Data description.

The output obtained using the data described above to run the models presented above is displayed and discussed in the next section.

5. THE RESULTS

5.1. Backshoring and employment growth in different manufacturing regions

The output of the first step of the empirical analysis, that is, testing if backshoring can affect the employment growth in the manufacturing sector, is displayed in .Footnote12 First, the results reveal that backshoring per se does not show any significant contribution to manufacturing employment growth (, column 1). At the aggregate level, the effects of job reinstatement through backshoring do not show up. This result may have different explanations. It can be that reindustrialisation is not associated with a decrease in FVA. But it can also be that local VA generated by the production of previously imported intermediate goods is generated by intensive production processes, through new automation and digital technologies (Añón Higón & Bonvin, Citation2022; Cassetta et al., Citation2020; Gopalan et al., Citation2022), so that the expansionary effects are registered on VA and not on employment. Or, lastly, it can be the average result of spatial heterogeneity in the impacts of backshoring on GVCs and employment dynamics.

Table 2. Backshoring and manufacturing employment growth.

In order to take the heterogeneity of regions into account, the empirical analysis estimates the effects of backshoring on regional manufacturing employment for traditional manufacturing and emerging manufacturing regions. Results show that the two groups of regions behave in an opposite way. Traditionally manufacturing backshoring regions register a higher employment growth than the others (, column 2), while employment performance performs worse than elsewhere in emerging manufacturing backshoring regions (, column 3).

This means that traditionally manufacturing backshoring regions are associated to expansionary production processes, relaunching the industrial vocation of Europe, and proving that we can still take advantage of the traditional know-how. A different story emerges for the other group of regions. In particular, emerging manufacturing regions seem to associate their launch of manufacturing activities to intensive production processes, obtained through efficiency gains via automation and digitalisation processes.

All these processes are, however, associated with the long term. In fact, looking at the marginal effects of our variables of interest (different types of backshoring) by period, it appears quite clearly that the overall results are evidently driven by the second period ().

Table 3. Backshoring marginal effects on manufacturing employment growth by period.

5.2. Backshoring and employment growth in different local labour markets

The final step of the empirical analysis is to capture the effects that backshoring generates in local labour markets when these are characterised by a different specialisation in high - or low-level manufacturing activities. This implies adding to the models presented above the interaction terms between high - and low-level regional functional specialisation and backshoring in different types of regions.

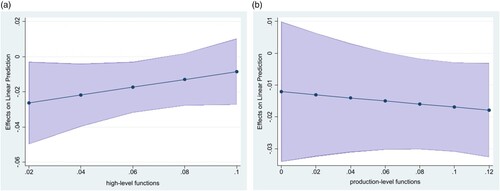

For clarity, full output tables are reported in Appendix 4 in the supplemental data online, while the main results in terms of marginal effects are graphically displayed in what follows, to facilitate the interpretation of the coefficients.

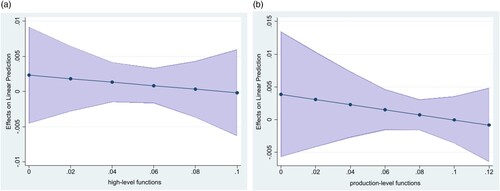

The overall marginal effects of backshoring on employment dynamics are not significant for increasing shares of high - (a) or low-level functions (b). This implies that backshoring is not associated with manufacturing job creation, and this is true independently of the type of functional specialisation of the local labour market in which it takes place. Confidence intervals are in fact at the 90% level and, as can be clearly seen, the marginal effects are never significant. Moreover, this is not a matter of short or long run, since the results are the same for the two periods analysed (see Figure A1 in Appendix 4 in the supplemental data online).Footnote13

Figure 4. Marginal effects of backshoring by increasing values of high-/low-level functions (90% confidence intervals – CIs).

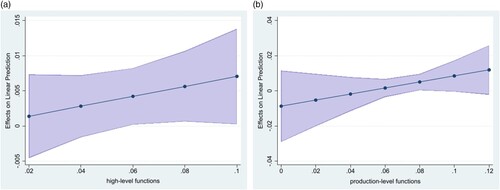

The case of traditionally manufacturing backshoring regions seems to be more interesting and to provide more thought-provoking results (). Not only the marginal effects of backshoring on employment dynamics in this category are overall positive and significant, but, particularly, they are statistically significant (and therefore even more effective) when measured in local labour markets with increasing intensity of decision-making (high-level) functions, suggesting that backshoring creates jobs also in areas highly characterised by the presence of decision making functions. a shows in fact a statistically significant marginal effect when the specialisation of the labour market in high-level functions is above the mean. The results are expanded to the labour markets with any level of high-level functions in the second period (see Figure A2 in Appendix 4 in the supplemental data online).

Even more appealing is the situation of local labour markets specialised in low-level functions (b). The positive effects of traditionally manufacturing backshoring regions are emphasised for increasing values of the share of low-level activities, witnessing that blue-collar jobs are created in these areas, relaunching their typical occupational vocations. This is again a relatively long-term process, as witnessed by the stronger results obtained in the second period (see Figure A2 in Appendix 4 in the supplemental data online).Footnote14

Figure 5. Marginal effects of backshoring by increasing values of high-/low-level functions in traditionally manufacturing regions (90% confidence intervals – CIs).

Also interesting is what can be observed for emerging manufacturing backshoring regions (). In this case, the results are totally different. The less expansionary job effects obtained on average become worse by decreasing the specialisation in high-level functions (a) or, inversely, by increasing the specialisation of low-level functions (b), witnessing that the increase of the share of manufacturing VA on which these regions are defined is the result of an intensive production process, obtained through efficiency gains from automation and digitalisation.Footnote15

Figure 6. Marginal effects of backshoring by increasing values of high-/low-level functions in emerging manufacturing regions (90% confidence intervals – CIs).

Summing up, these results clearly show how traditionally dynamic manufacturing regions can in fact effectively revitalise their historical vocation through backshoring, generating a manufacturing employment growth which is higher with respect to the other regions and that involves both low - and high-level occupations.

In emerging dynamic manufacturing regions, instead, backshoring does not produce the same effects. In this case, the process favours manufacturing employment growth much less than in the other regions and could be, instead, more related to a valuable performance, possibly characterised by automation, innovation, VA, and specific skills, detrimental to an overall employment growth.

These outcomes reveal quite clearly how a backshoring strategy aimed at revitalising the dynamic of employment in manufacturing at the European level cannot neglect the important differences existing among regions in terms of the different possible ways in which they reduce dependence, depending on their endogenous characteristics.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Drawing its motivation on the European institutional calling for the protection of industrial vocation, the relaunch of manufacturing employment and reindustrialisation, this study is a first attempt to understand the effects of backshoring on local manufacturing employment dynamics. It does so with an original perspective on the topic, starting from a conceptual and operational definition of backshoring at the aggregate regional level and developing an analysis for NUTS-2 areas in Europe taking into consideration different manufacturing regions and different types of local labour markets.

Backshoring regions were identified as those concurrently reducing their import of foreign intermediate goods contained in their exports and reindustrialising, taking advantage from the EUREGIO input–output regional database. The results signalled the linkage between backshoring and the dynamics of employment in manufacturing is not straightforward, and in fact it differs depending on the characteristics of the areas. While backshoring per se does not affect significantly manufacturing employment growth, in areas increasing their specialisation in manufacturing and characterised by a historical manufacturing vocation, a positive effect emerges, especially in terms of relaunch of both high-level and production functions, signalling an extensive production pattern.

In emerging manufacturing areas, the opposite is true: in these areas backshoring creates less jobs than in the others and this is true especially in local labour markets specialised in low-level activities. This witnesses that the increase in the share of manufacturing VA occurs through increments in productivity according to an intensive production pattern.

This is notably interesting, since the EU seems to pursue two concurrent objectives in terms of modern reindustrialisation and relaunch of manufacturing employment. Although they are both widely acceptable, it is particularly important to consider that they are potentially in conflict within the same region (Resmini et al., Citation2024). Our analysis suggests that the two strategies have to be applied wisely. Modern reindustrialisation strategies can be pursued in some emerging manufacturing areas, while a relaunch of manufacturing employment strategy seems to be more effective in traditionally manufacturing regions. Once again, this calls for industrial policies specific for groups of regions.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (369.7 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. For a comprehensive literature review on reshoring, see Pedroletti and Ciabuschi (Citation2023).

2. The values are compared based on the compound growth rates in the two periods. In order to be sure that a post-crisis period was captured, we avoided 2011 and 2012 when some EU countries were still suffering from the crisis.

3. This definition is even stricter with respect to that applied by Capello and Cerisola (Citation2023a, Citation2023b), where reindustrialisation includes situations of increasing shares of manufacturing value added in the first period.

4. See Capello and Cerisola (Citation2023a) for additional reflections on this indicator.

5. The analysis involves NUTS-2 regions in the EU28 countries (EU27 + UK), except Romania and Bulgaria (for which regional data on GVCs are not available) and Croatia (for which data on GVCs are not available at all). Regional trade in value added data for Slovenia and Lithuania are also not available, but, given their small size, they are included in the analysis at NUTS-0 level.

6. The years 2020 and 2021 were avoided to catch a general and generalisable result, instead of the buzz generated by the pandemic.

7. See https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/metropolitan-regions/background (accessed on 11 July 2023).

8. Specialisation in manufacturing is measured through a location quotient based on VA in manufacturing, with country as the reference unit.

9. A random fixed effect model with the same structure here proposed provides exactly the same results.

10. In practical terms, we generate a dummy variable representing backshoring in different types of regions. We prefer this strategy instead of interacting the backshoring variable with the regional typologies since in the base regression we use an interaction with time, which becomes a triple interaction when we also include the role of functions. Different specifications would imply a four-variables interaction, which would be very likely to be unstable and hard to interpret. In any case, as a robustness check, the version with interaction between the backshoring variable with the regional typologies was run. The results remain consistent and are available from the authors upon requests.

11. A more sophisticated analysis could be carried out with tasks, rather than functions, as suggested by Acemoglu and Autor (Citation2011). Regional data of tasks are, however, not officially available.

12. As a robustness check, the regressions were also run adding one control variable at a time. The results are fully robust and are reported in Appendix 3 in the supplemental data online.

13. The coefficients on which is based are fully reported in Table A5 in Appendix 4 in the supplemental data online.

14. The coefficients on which is based are fully reported in Table A6 in Appendix 4 in the supplemental data online.

15. The coefficients on which is based are fully reported in Table A7 in Appendix 4 in the supplemental data online.

REFERENCES

- Accetturo, A., & Giunta, A. (2016). Value chains and the great recession: Evidence from Italian and German firms (Occasional Papers No. 304). Banca d’Italia, Questioni di Economia e Finanza.

- Acemoglu, D., & Autor, D. (2011). Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. In D. Card, & O. Ashenfelter (Eds.), Handbook of labour economics (Vol. 4B (4), pp. 1043–1171). Elsevier.

- Aghion, P., Bergeaud, A., Boppart, T., Klenow, P. J., & Li, H. (2019). Missing growth from creative destruction. American Economic Review, 109(8), 2795–2822. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20171745

- Altomonte, C., Di Mauro, F., Ottaviano, G., & Vicard, V. (2012). Global value chains during the great trade collapse: A bullwhip effect? (ECB Working Paper No. 1412).

- Álvareza, I., Biurruna, A., & Martín, V. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 on European global value chains: Some concerns about diversification and resilience. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 14(7), 1745–1760. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2021.1983928

- Amador, J., Cappariello, R., & Stehrer, R. (2015). Global value chains: A view from the euro area (ECB Working Paper No. 1761, March).

- Añón Higón, D. & Bonvin, D. (2022). Information and communication technologies and firms’ export performance. Industrial and Corporate Change, 31(4), 955–979. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtac017

- Araujo, S., & Oliveira Martins, J. (2009). The great synchronisation: Tracking the trade collapse with high frequency data. Open access publications from Université Paris-Dauphine 8088.

- Ascani, A., Bettarelli, L., Resmini, L., & Balland, P. (2020). Global networks, local specialisation and regional patterns of innovation. Research Policy, 49(8), 104031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104031

- Baldwin, R. (2009a). The great trade collapse: Causes, consequences and prospects. VoxEU.org. https://cepr.org/system/files/publication-files/68568-the_great_trade_collapse_causes_consequences_and_prospects.pdf

- Baldwin, R. (2009b). The great trade collapse: What caused it and what does it mean? In R. Baldwin (Ed.), The great trade collapse: Causes, consequences and prospects, VoxEU.org (pp. 1–16). https://cepr.org/system/files/publication-files/68568-the_great_trade_collapse_causes_consequences_and_prospects.pdf

- Barbieri, P., Boffelli, A., Elia, S., Fratocchi, L., Kalchschmidt, M., & Samson, D. (2020). What we can learn about reshoring after COVID-19? Operations Management Research, 13(3–4), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-020-00160-1

- Bettarelli, L., & Resmini, L. (2022). The determinants of FDI: A new network-based approach. Applied Economics, 54, 5257–5272. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2022.2041184

- Boffelli, A., & Johansson, M. (2020). What do we want to know about reshoring? Towards a comprehensive framework based on a meta-synthesis. Operations Management Research, 13(1–2), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-020-00155-y

- Boschma, R., Minondo, A., & Navarro, M. (2012). Related variety and regional growth in Spain. Papers in Regional Science, 91(2), 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1435-5957.2011.00387.x

- Brenton, P., Ferrantino, M., & Maliszewska, M. (2022). Reshaping global value chains in light of COBIV-19. World Bank.

- Camagni, R. (2016). Territorial capital and regional development: Theoretical insights and appropriate policies. In R. Capello, & P. Nijkamp (Eds.), Handbook of regional growth and development theories (pp. 124–148). Edward Elgar.

- Camagni, R. (2024). Adam Smith (1723-1790): Uncovering his legacy for regional science. Scienze Regionali, Italian Journal of Regional Science, 1/2024, 3-64. doi:10.14650/112422

- Camagni, R., Capello, R., & Perucca, G. (2022). Beyond productivity slowdown: Quality, pricing and resource reallocation in regional competitiveness. Papers in Regional Science, 101(6), 1307–1330. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12696

- Capello, R., & Cerisola, S. (2023a). Regional reindustrialization patterns and productivity growth in Europe. Regional Studies, 57(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2050894

- Capello, R., & Cerisola, S. (2023b). Regional transformations processes: Reindustrialization and technological upgrading as drivers of productivity gains. In R. Capello, & A. Conte (Eds.), Cities and regions in transition (pp. 19–38). Franco Angeli.

- Capello, R., & Lenzi, C. (2013). Innovation and employment dynamics in European regions. International Regional Science Review, 36(3), 322–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160017612462874

- Cassetta, E., Monarca, U., Dileo, I., Di Berardino, C., & Pini, M. (2020). The relationship between digital technologies and internationalisation. Evidence from Italian SMEs. Industry and Innovation, 27(4), 311–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2019.1696182

- Cattaneo, O., Gereffi, G., & Staritz, C. (Eds.). (2010). Global value chains in a postcrisis world – A development perspective. World Bank.

- Ciffolilli, A., & Muscio, A. (2018). Industry 4.0: National and regional comparative advantages in key enabling technologies. European Planning Studies, 26(12), 2323–2343. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1529145

- Coveri, A., Paglialunga, E., & Zanfei, A. (2022). Global value chains, functional diversification and within-country inequality: An empirical assessment. https://ssrn.com/abstract=4603958; http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4603958; https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4603958

- Dachs, B., Kinkel, S., Jäger, A., & Palčič, I. (2019). Backshoring of production activities in European manufacturing. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 25(3), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2019.02.003

- De Backer, K., Menon, C., Desnoyers-James, I., & Moussiegt, L. (2016). Reshoring: Myth or reality? (OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers No. 27). OECD Publ. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5jm56frbm38s-en.pdf?expires=1695384968&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=F5EC87BB9216ADD1ED22601CD4F28344

- Di Mauro, C., Fratocchi, L., Orzes, G., & Sartor, M. (2018). Offshoring and backshoring: A multiple case study analysis. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 24(2), 108–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2017.07.003

- Dikler, J. (2021). Reshoring: An overview, recent trends, and predictions for the future. World Economy Brief, 11(35), 1–10.

- Elia, S., Fratocchi, L., Barbieri, P., Boffelli, A., & Kalchschmidt, M. (2021). Post-pandemic reconfiguration from global to domestic and regional value chains: The role of industrial policies. Transnational Corporations, 28(2), 67–96. https://doi.org/10.18356/2076099x-28-2-3

- Ellram, L. M. (2013). Offshoring, reshoring and the manufacturing location decision. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 49(2), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12023

- Eriksson, R., Lindgren, U., & Malmberg, G. (2008). Agglomeration mobility: Effects of localisation, urbanisation, and scale on job changes. Environment and Planning A, 40(10), 2419–2434. https://doi.org/10.1068/a39312

- European Commission. (2010). An integrated industrial policy for the globalisation era putting competitiveness and sustainability at centre stage. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM(2010) 614 final.

- European Commission. (2012). A stronger European industry for growth and economic recovery. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM(2012) 582 final.

- European Commission. (2014). For a European industrial renaissance. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM(2014) 14 final.

- European Commission. (2021). Cohesion in Europe Towards 2050 – Eighth report on economic, social, and territorial cohesion. European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/reports/cohesion8/8cr.pdf

- European Commission. (2022). EU strategic autonomy 2013–2023. From concept to capacity. European Union. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2022/733589/EPRS_BRI(2022)733589_EN.pdf

- Foerstl, K., Kirchoff, J. F., & Bals, L. (2016). Reshoring and insourcing: Drivers and future research directions. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 46(5), 492–515. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-02-2015-0045

- Fratocchi, L., Di Mauro, C., Barbieri, P., & Nassimbeni, G. (2014). When manufacturing moves back: Concepts and questions. Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, 20(1), 54–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2014.01.004

- Fuster, B., Martínez-Mora, C., & Lillo-Bañuls, A. (2023). Does reshoring generate employment? A study on services reshoring and Its intra- and inter-sectoral components. SAGE Open, 13(3), 21582440231202319. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231202319

- Gao, X., Hewings, G. J., & Yang, C. (2022). Offshore, re-shore, re-offshore: What happened to global manufacturing location between 2007 and 2014? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15(2), 183–206.

- Gereffi, G. (2020). What does the COVID-19 pandemic teach us about global value chains? The case of medical supplies. Journal of International Business Policy, 3(3), 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00062-w

- Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J., Kaplinsky, R., & Sturgeon, T. J. (2001). Introduction: Globalisation, value chains and development. IDS Bulletin, 32(3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2001.mp32003001.x

- Gopalan, S., Reddy, K., & Sasidharan, S. (2022). Does digitalization spur global value chain participation? Firm-level evidence from emerging markets. Information Economics and Policy, 59, 100972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoecopol.2022.100972

- Holz, R. (2009). An investigation into offshoring and backshoring in the German automotive industry [PhD Thesis]. University of Wales, Swansea.

- Johansson, M., & Olhager, J. (2018). Manufacturing relocation through offshoring and backshoring: The case of Sweden. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 29(4), 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-01-2017-0006

- Johansson, M., Olhagera, J., Heikkiläb, J., & Stentoftc, J. (2019). Offshoring versus backshoring: Empirically derived bundles of relocation drivers, and their relationship. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 25(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2018.07.003

- Karatzas, A., Ancarani, A., Fratocchi, L., Di Stefano, C., & Godsell, J. (2022). When does the manufacturing reshoring strategy create value? Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 28(3), 100771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2022.100771

- Kearney. (2020). Trade war spurs sharp reversal in 2019 reshoring index, foreshadowing COVID-19 test of supply chain resilience. https://www.kearney.com/documents/291362523/291368730/2020+Reshoring+Index.pdf/ba38cd1e-c2a8-08ed-5095-2e3e8c93e142?t=1608449589000

- Kearney. (2023). America is ready for reshoring. Are you? https://www.kearney.com/service/operations-performance/us-reshoring-index

- Kinkel, S. (2014). Future and impact of backshoring – Some conclusions from 15years of research on German practices. Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management, 20(1), 63–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2014.01.005

- Kinkel, S., & Maloca, S. (2009). Drivers and antecedents of manufacturing offshoring and backshoring – A German perspective. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 15(3), 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2009.05.007

- Krenz, A., Prettner, K., & Strulik, H. (2021). Robots, reshoring, and the lot of low-skilled workers. European Economic Review, 136, 103744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2021.103744

- Krenz, A., & Strulik, H. (2021). Quantifying reshoring at the macro-level. Measurement and applications. Growth and Change, 52(3), 1200–1229. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12513

- Mackay, R. R. (2006). Local labour markets, regional development and human capital. Regional Studies, 27(8), 783–795. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409312331347975

- Marin, D. (2018). Global value chains, the rise of the robots and human capital”. Wirtshaftsdienst, 98(S1), 46–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10273-018-2276-9

- Martinez-Mora, C., & Merino, F. (2014). Offshoring in the Spanish footwear industry: A return journey? Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 20(4), 225–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2014.07.001

- Pedroletti, D., & Ciabuschi, F. (2023). Reshoring: A review and research agenda, Journal of Business Research, 164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114005

- Pegoraro, D., De Propris, L., & Chidlow, A. (2022). Regional factors enabling manufacturing reshoring strategies: A case study perspective. Journal of International Business Policies, 5(1), 112–133. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-021-00112-x

- Piva, M., & Vivarelli, M. (2005). Innovation and employment: Evidence from Italian microdata. Journal of Economics, 86(1), 65–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00712-005-0140-z

- Quatraro, F. (2010). ‘Knowledge coherence, variety and economic growth. Manufacturing evidence from Italian regions’. Research Policy, 39(10), 1289–1302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2010.09.005

- Resmini, L., Bettarelli, L., Calogero, V., Comi, S., & Grasseni, M. (2024). One does not fit all: The heteregenous impact of BITs on regions participating in GPNs. Papers in Regional Science, 103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pirs.2024.100013.

- Savi, P. (2019). Trasformazioni recenti della geografia della produzione: Il backshoring e la sua diffusione nel contesto italiano. Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana Serie, 14, 2(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.13128/bsgi.v2i1.801

- Sirkin, H. L., Zinser, M., & Hohner, D. (2011). Made in America, again – Why manufacturing will return to the U.S. BCG. https://www.nist.gov/system/files/documents/2017/05/09/file84471.pdf

- Sirkin, H. L., Zinser, M., Hohner, D., & Rose, J. (2012). U.S. manufacturing nears the tipping point – Which industries? Why? And how much? BCG. https://web-assets.bcg.com/img-src/BCG_US_Manufacturing_Nears_the_Tipping_Point_Mar_2012_tcm9-106751.pdf

- Srai, J. S., & Ane, C. (2016). Institutional and strategic operations perspectives on manufacturing reshoring. International Journal of Production Resources, 54(23), 7193–7211. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2016.1193247

- Thi Thu Huong, N., & Park, D. (2021). Does global value chain participation enhance export diversification? Korea and the World Economy, 22(3), 159–191. https://doi.org/10.46665/kwe.2021.12.22.3.159

- Thissen, M., Lankhuizen, M., van Oort, F., Los, B., & Diodato, D. (2018). EUREGIO: The construction of a global IO DATABASE with regional detail for Europe for 2000–2010 (No. 18-084/VI; Tinbergen Discussion Paper).

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2020). World investment report. United Nations. https://unctad.org/publication/world-investment-report-2020

- US Reshoring Initiative. (2020). Two milestones: Reshoring surges to record high. Cumulative jobs announced surpasses 1 million jobs. https://reshorenow.org/content/pdf/RI_2020_Data_Report.pdf

- Zanin, L., & Calabrese, R. (2017). Interaction effects of region-level GDP per capita and age on labour market transition rates in Italy. IZA Journal of Labor Economics, 6(1), 1–29. https://econpapers.repec.org/article/sprizalbr/