ABSTRACT

This article investigates how paired electoral quotas re-distribute parliamentary seats between majority and minority groups. Focusing on gender and youth quotas, we use the concept of Hierarchies of Representation to analyse the political inclusion of intersectional groups. We use a dataset of 146 countries and two case studies to explore quotas’ effects on HoR under different quota constellations. We find that paired quotas tend to re-distribute power among women and youth rather than challenge middle-aged men’s parliamentary dominance.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The under-representation of youth in formal politics is nearly as striking as the lack of women: people between the ages of 20 and 39Footnote1 make up over 40% of the world’s voting age population, but only 17% of members of parliament (MPs) (Inter-Parliamentary Union, Citation2018, p. 8). Young women appear to be doubly disadvantaged, providing only about 2.3% of the world’s MPs (Inter-Parliamentary Union, Citation2018, p. 19). Several states, mostly in the Global South, as well as political parties have recently introduced electoral quotas to increase the political representation of young citizens (Belschner, Citation2018). To date, youth quotas exclusively occur in tandem with gender quotas: All parties with youth quotas also apply gender quotas and all states with legislated youth quotas simultaneously or previously adopted quotas for women. Is this institutional configuration a remedy against young women’s underrepresentation?

Research has shown the significant impact of gender quotas on the share of women MPs (Dahlerup, Citation2008; Hughes, Paxton, Clayton, & Zetterberg, Citation2019; Schwindt-Bayer, Citation2009; Tripp & Kang, Citation2008) and their intersectional effects, mostly with a focus on gender and ethnicity (Bird, Citation2014, Citation2016; Htun, Citation2016; Hughes, Citation2011, Citation2016). Especially when dealing with multiple quotas for different groups, the question of quotas’ re-distributive power arises. If minority groups gain parliamentary seats, where do those come from? Or, put differently: ‘If women win, who loses?’ (Childs & Hughes, Citation2018, p. 284).

This article suggests a conceptual framework to systematically measure and compare descriptive group representation at the intersection of identities that we term ‘hierarchies of representation’ (HoR). Theoretically, the concept relies on intersectionality approaches to political representation, claiming that hierarchies within groups are as influential for representational outcomes as hierarchies between groups (Hancock, Citation2007; Htun & Ossa, Citation2013; Mügge, Montoya, Emejulu, & Weldon, Citation2018; Mügge & Erzeel, Citation2016).

HoR are conceptualised as minority and majority groups’ odds for representation, i.e. a specific group’s chances to be elected to parliament relative to another group. It contributes to intersectional analyses of group representation by offering a consistent way to measure and thus compare the extent and direction of under- and overrepresentation of any identifiable societal groupFootnote2 across space and time, because it includes a variable for groups’ actual share in populations. While the share of women in populations tends to be at a stable 50%, this is not the case for most other groups. For example, (specific) ethnic groups’ or also youth’s share in populations will differ both over time and across states and regions. HoR accommodates for this fact and is thus particularly applicable for the comparative study of intersectional groups’ representation.

Empirically, we analyse how paired quotas for women and youth are connected to gender and age groups’ odds for representation and thus the HoR between and within groups. First, we use an original dataset based on survey data from 146 parliaments worldwide to explore the HoR between gender and age groups across space, i.e. under different combinations of institutional settings and quotas. We find that, while youth quotas do not significantly increase young peoples’ nor young women’s absolute share in parliaments, they do affect the seat distribution among minority groups.

In order to investigate how the pairing of differently designed quotas moderates those findings, we complement the analysis with a comparative case study of gender and youth quotas’ intersectional effects in Tunisia and Morocco. The cases each represent a specific combination of paired quotas (legislated candidate quotas in Tunisia and reserved seats in Morocco)Footnote3 and allow us to compare quotas’ effects in in varying contexts. Both countries employ PR-list electoral systems, have first introduced single gender quotas, and later added youth quotas. Both did so in the aftermath of the Arab Uprisings in 2011 (Belschner, Citation2018). While the countries are comparable in terms of geographical location, sharing regional and cultural proximity, they differ in the degree of democracy and societal gender equality.

Using electoral data over time, we compare how the HoR between young and middle-aged to old women and men changed after the introduction of a youth quota additional to an existing gender quota. The findings suggest that paired gender and youth quotas tended to re-distribute power between minorities, but did not challenge middle-aged to old men’s overrepresentation. While both paired quotas increased young women’s odds for representation considerably, they did so mostly at the expense of young men rather than middle-aged men.

The article complements accounts about ‘what kinds’ of – male and female – candidates benefit from electoral quotas (Franceschet, Krook, & Piscopo, Citation2012, p. 10; Freidenvall, Citation2016) and sheds light on the dynamic nature of quotas’ impact on intersectional patterns of representation.

Several studies have demonstrated that the institutional conditions under which candidate selection processes take place influence parties’ logics of acting (Bird, Citation2016; Childs & Hughes, Citation2018; Htun & Ossa, Citation2013; Randall, Citation2016). At times this means privileging minority men over women (Black, Citation2000; Hughes, Citation2016), supporting the ‘double jeopardy’ hypothesis (Mügge & Erzeel, Citation2016), and at others privileging minority women, exemplifying the ‘multiple advantages’ hypothesis (Celis & Erzeel, Citation2017; Freidenvall, Citation2016). This article aims to reconcile those two hypotheses by offering a concept that encompasses the ‘it depends’ component and that tries to accommodate for dynamic rather than static hierarchical relations between and within groups (Bird, Citation2014; Htun & Ossa, Citation2013). By focusing on age as a structuring element of (dis)advantage in politics, the article also adds to the emerging literature on youth’s political representation (Belschner, Citation2018; Erikson & Josefsson, Citation2019; Joshi, Citation2015; Stockemer & Sundström, Citation2018, Citation2019).

Hierarchies of Representation: Measuring and Comparing Descriptive Representation

A considerable body of literature deals with the specific conditions for the political representation of minority groups. While analyses initially focused on the separate study of groups like women, ethnic minorities, and youth, a growing literature rooted in Black Feminism investigates structural inequalities of groups located at the intersection of several (group) identities (Cho, Crenshaw, & McCall, Citation2013; Collins & Bilge, Citation2016; Hancock, Citation2007). Intersectionality upholds that the experiences of structural group belonging can be marginalising and privileging at the same time and that ‘social groups and individuals are fundamentally hybrid’ (Htun & Ossa, Citation2013, p. 6; Weldon, Citation2008).

With regards to the political representation of intersectional groups, there tend to be two opposing hypotheses about how individuals belonging to two marginalised groups at a time are structurally affected (Mügge & Erzeel, Citation2016). One the one hand, they may be ‘doubly jeopardised’ meaning that representational disadvantages may be cumulative. On the other hand, there may also be ‘complementarity advantages’ available to these individuals (Celis & Erzeel, Citation2017).

While there is empirical evidence for both of these hypotheses, we suggest that outcomes of political representation for groups at the intersection of inequalities are dependent on context and, crucially, on the answer to the question of ‘who should be compared to whom?’ (Freidenvall, Citation2016, p. 359). Therefore, we introduce the concept of HoR that allows measuring and comparing the varying hierarchies between and within groups’ descriptive representation across space and over time.

Inspired by Hughes (Citation2011), we define HoR as the odds for representationFootnote4 of different, mutually exclusive groups, accounting for their share in population or among candidates. In general, the odds are the ratio of the probability that an event occurs to the probability that it does not, or, in our case, the likelihood to be represented in parliament for a reference group vs. a comparison group (Bland & Altman, Citation2000). Methodologically speaking, the odds ratio is a conditional probability and calculated as a*d / b*c. For our purposes, a is the number of MPs in the reference group, b is the number of the reference group in population (or candidates), c is the number of MPs in the comparison group, and d is the number of the comparison group in population (or candidates). This way, we are able to calculate a relative chance of an individual belonging to a specific (intersectional) group to be elected to parliament compared to another individual – and to see how the odds for each group change under different institutional settings. Whereas an odds ratio of 1 signifies equal chances for both groups to be represented, a value smaller/greater than 1 means worse/better chances for the reference group, respectively. For example, an odds ratio of 0.5 would translate into a 1:2 chance for the reference group to be represented relative to the comparison group.

While the idea of hierarchies between and within groups is well established in the literature on intersectionality (Htun & Ossa, Citation2013; Hughes, Citation2016; Mügge & Erzeel, Citation2016; Weldon, Citation2008), our concept of HoR formalises the dynamic structure of those hierarchies by including variables of reference and comparison of group’s shares in populations/candidates connected to their political representation. In contrast to for example QCA-based approaches (Lilliefeldt, Citation2012), the odds ratio is variable-centred and can thus potentially be applied to analyse representational dynamics in any country or party case.Footnote5

HoR thus has two specific offers: First, it allows comparing different intersectional groups’ representation across space. Whereas women constitute more or less 50% of all populations worldwide, other marginalised groups’ share in populations considerably varies between cases and regions. For example, youth’s share in populations in the Global South tends to be higher than in countries of the Global North – thus, equal representation of groups would require higher shares of young parliamentarians in the former countries. Second, HoR allow examining change in intersectional representation over time within cases.

While the under-representation of women in politics is the subject of a large body of literature and some studies have focused on elder women politicians (Randall, Citation2016), research on youth in formal politics is only emerging (Joshi, Citation2013, Citation2015; Stockemer & Sundström, Citation2018). A good share of this literature indeed takes an intersectional approach to the study of youth, recognising the specific conditions for young women’s representation (Erikson & Josefsson, Citation2019; Evans, Citation2016; Joshi & Och, Citation2014; Stockemer & Sundström, Citation2019).

Since 2014, the Inter-Parliamentarian Union conducts biannual surveys on the share of gender and age groups in parliaments worldwide (Inter-Parliamentary Union, Citation2014, Citation2016, Citation2018). While the conceptualisation of age groups is less straightforward than when talking about gender or ethnic minority/majority status, a common definition of ‘youth’ in political representation spans from 20 to 39 years of age. This allows taking into account that some parliaments have relatively high minimum age requirements and that, in general, young people rarely gain office before the age of 35 (Inter-Parliamentary Union, Citation2016, p. 5). Accordingly, in this study, we use 40 as the main cut-off age between young and middle-aged. While this definition seems broad, it is preferable over a too narrow definition – if 40-year olds are underrepresented, this will arguably also be true for 30- and 35-year olds, but not vice-versa. Furthermore, 40 is the maximum cut-off age employed in the design of youth quotas.

For the purpose of this article, we have conceptualised gender and age groups as middle-aged to old men (≥ 40 years of age), middle-aged to old women, young men (20–39 years of age), and young women. One limitation of our approach to measure hierarchies of representation as an odds ratio is that it works best with dichotomous groups that are cross compared to each other. While we concede that a more fine-grained conceptualisation of age groups, differentiating for example further between the middle-aged and the elderly, would offer further insights into the representational dynamics at play, it would also complicate the analysis to an important degree.Footnote6 Therefore, the results presented in the following should be read as being focused on youth and gender, rather than providing a complete picture of age dynamics in political representation.

The Intersectional Effects of Gender and Youth Quotas

Gender quotas have become one of the most popular electoral reforms worldwide: In more than 130 countries, some kind of gender quota is in effect (Hughes et al., Citation2019). There is also a growing consensus about the importance to include youth in institutionalised politics, that is, in parties and parliaments (Inter-Parliamentary Union, Citation2018; UNDP, Citation2013). By 2018, eight states have adopted legislated youth quotas; and so did (at least) 16 individual parties in different countries (see overview in ).

Table 1. Youth and gender quotas after quota type.

As stated, youth quotas so far always occur together with gender quotas (Belschner, Citation2018). displays the distribution of youth and gender quotas according to the respective quota types. Youth quotas, like gender quotas, take the form of legislated candidate quotas (LCQ), reserved seats (RS), or Party quotas (PQ) (Krook, Citation2014). LCQ and RS are both legislated and thus apply to all parties in a political system, whereas party quotas are adopted internally. Legislated gender and youth quotas are so far always designed similarly. Except for Rwanda, where there exists a double gender quota, states either adopt candidate quotas for both women and youth (LCQLCQ) or reserve parliamentary seats for both groups (RSRS). This is an important difference to paired quotas for women and ethnic minorities that tend to be more heterogeneous in their designs, even if they both occur in one country (Bird, Citation2014, Citation2016; Htun, Citation2004). The composition of gender/youth quotas on the party level is more mixed: A number of European countries, as well as Mozambique and Viet Nam, have at least one party that uses both gender and youth quotas (PQPQ). On the other hand, some Latin American and African countries as well as Croatia and Montenegro employ legislated gender quotas and one or several parties additionally adopted internal youth quotas (LCQPQ).

Previous research on the intersectional effects of electoral quotas has so far mainly studied gender and ethnic quotas. Focusing on the re-distributive effects of quotas, Hughes finds that, as standalone policies, both gender and ethnic minority quotas tend to benefit primarily majority women and minority men, respectively (Hughes, Citation2011, p. 616). The explanation Hughes provides is that a gender quota forces the political parties to nominate more women. They will choose ‘majority women’, i.e. those with the highest political capital who have the greatest chance to win elections. This refers back to the ‘double jeopardy’ hypothesis and may as well translate to a preference for middle-aged women when speaking about the effect of single gender quotas on age groups’ odds for election.

H1 (double jeopardy): Single gender quotas privilege the representation of middle-aged women over young women.

In the same vein, single youth quotas (that empirically do not exist to date) would be expected to benefit young men.

In contrast, Hughes finds that when quotas are paired, minority women’s parliamentary representation increases over-proportionally. She argues that parties will strive to fulfil both quotas by nominating one candidate – a minority woman – to unseat fewer incumbents. This would resonate with the ‘complementary advantages’ hypothesis (Celis & Erzeel, Citation2017).

As Bird (Citation2016) points out, the intersectional effects of paired quotas may however be influenced by the type and design of the quotas under question. She differentiates between ‘dual’ and ‘nested’ paired quotas for women and ethnic minorities. Dual quotas co-exist and operate independently from each other,Footnote7 whereas nested quotas mutually apply to each other (Bird, Citation2016, p. 289). Only nested quotas should in this perspective be expected to produce favourable outcomes for minority women, i.e. complementarity advantages, whereas dual quotas must analytically be treated as doubled single quotas, continuing to favour majority women and minority men, respectively. In the case of gender and youth quotas, the differentiation of dual/nested quotas mostly corresponds to reserved seats/legislated candidate quotas. Whereas reserved seats for women and youth exist independent from each other – meaning that there are commonly no reserved seats for youth among the women’s seats, nor reserved seats for women among the youth seatsFootnote8 – legislated candidate quotas usually apply to the same party lists and can thus be regarded as nested. Accordingly, we expect the following:

H2 (complementary advantages): Nested candidate quotas for women and youth (LCQLCQ) privilege young women’s representation relative to middle-aged women and young men.

H3 (double jeopardy): Dual reserved seats for women and youth (RSRS) privilege the representation of middle-aged women and young men over young women, respectively.

Thus, we hypothesise that paired quotas’ effects on the HoR between and within groups – conceptualised as double jeopardy or complementary advantages for young women – vary depending on the specific quota system in place.

In the following, we will first provide information about the methods and data used in this article, before we empirically explore the variation of gender and age groups’ representation in parliaments worldwide. We then continue with our case studies to trace the working of gender and youth quotas over time.

Methods, Data, and Case Selection

This article combines the exploration of an original dataset on youth representation with two case studies, where we compare the intersectional effects of differently designed gender and youth quotas over time.

The dataset is composed of survey data collected by the Inter-Parliamentarian Union (IPU) from 2015 to 2017. It provides the (aggregated) number of members of parliaments (MPs), divided after gender and age groups, in 146 parliaments worldwide. This data is so far unpublished and has been provided to the authors by the IPU. We then supplemented data on youth’s share in the populationFootnote9, electoral systems, and the different electoral quotas in use. Population data was collected from the UN Statistics division. We always recorded the newest available data and aggregated population figures for the following groups: Middle-aged to old men, middle-aged to old women, young men, and young women. Information about the electoral system in place, coded as Proportional Representation (PR), Majority-Plurality (MP), or mixed, was obtained from the International IDEA Electoral Systems database (Electoral System Design Database | International IDEA). We also included a variable on if a country has an effective gender quota in place, taken from the recent QAROT dataset (Hughes et al., Citation2019),Footnote10 as well as information on the types of gender and youth quotas employed. The quantitative analyses rely on that dataset compiled in spring 2019.

The dataset is useful to explore general dynamics of representation regarding age and gender but reaches its limits when analysing the specific impact of paired gender and youth quotas. Since only eight countries so far have introduced national youth quotas and since those are differently designed, the number of cases becomes too small for cross-country regressions. Therefore, we continue with two case studies to trace how different forms of legislated paired quotas affect HoR within cases over time. Tunisia and Morocco are selected as representative cases for the two above-mentioned legislated quota configurations (LCQLCQ and RSRS).Footnote11 Since LCQLCQ and RSRS are legislated quotas, we analyse them on the country level and include groups’ share in populations in the calculation of the resulting HoR.Footnote12

The cases of Tunisia and Morocco allow us to compare HoR before and after the introduction of a youth quota additional to an existing gender quota and thus to test the hypotheses formulated above. Both countries employ a PR list electoral system and introduced electoral youth quotas additional to existing gender quotas after the Arab Uprisings in 2011. While the quotas take the form of legislated candidate quotas (LCQLCQ) in Tunisia, they occur as reserved seats for both groups (RSRS) in Morocco.

The Political Representation of Gender and Age Groups Worldwide

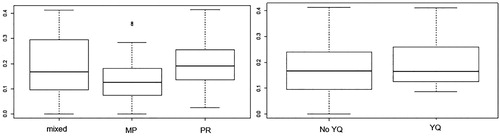

This section explores gender and age groups’ representation in parliaments worldwide. provides an overview of the share of young parliamentarians worldwide.

The plots visualise variation in different electoral systems and in countries with or without youth quotas. Similar to what we know about women’s representation, proportional representation and mixed electoral systems seem to be slightly more favourable for higher shares of young parliamentarians.Footnote13 The second plot in reveals that countries where a youth quota is in place do not have higher shares of youth in parliament, on average.

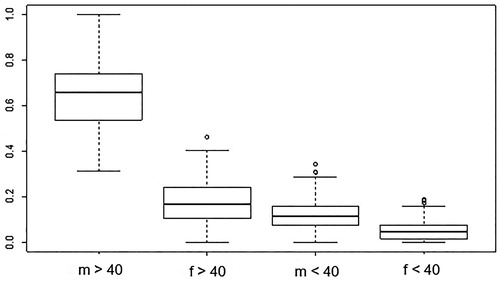

further differentiates the age groups (young and middle-aged to old) after gender. Visualising the shares of intersectional gender and age groups in parliaments, it shows that middle-aged to old men form the great majority of MPs in almost all cases, followed by middle-aged to old women, young men, and young women. Thus, although the gender imbalance is more pronounced among the middle-aged to old MPs than among the young MPs, the combined gender and age imbalances clearly show that young women are least represented.Footnote14

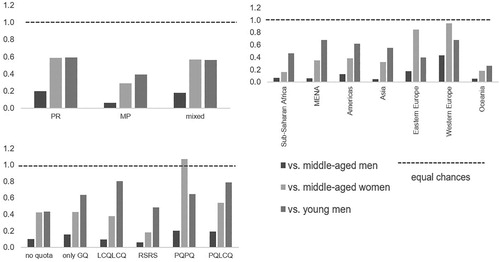

then focuses on young women’s odds of representation relative to the other groups in varying regions and under different institutional conditions. The dotted line delimits an odds-ratio of 1, i.e., equal chances. As shown for youth in general, PR and mixed electoral systems are also comparatively more favourable for young women’s chances to be represented than majoritarian systems. Across world regions, young women’s odds for representation are steadily lowest when compared to middle-aged men. However, their odds compared to other groups vary. Interestingly, they have comparatively better chances relative to middle-aged to old women than relative to young men in Europe. Put differently, in Europe, the gender disadvantage seems to be more pronounced than the age disadvantage. In the other world regions, in contrast, the age disadvantage seems to weigh more heavily. Here, young women’s chances for election are higher relative to young men than relative to middle-aged women.

Besides demography – the fact that young peoples’ share in population is much lower in Europe than in Africa and Asia – this could be an effect of the high prevalence of electoral gender quotas in the latter regions. Indeed, as shown by the third plot in , effective gender quotas (only GQ) slightly reduce young women’s chances to be represented relative to middle-aged women but increase them relative to young men.

The plot also confirms that HoR vary under different combinations of gender and youth quotas. Nested legislated candidate quotas (LCQLCQ) seem to increase young women’s chances for representation relative to young men, while their chances relative to middle-aged women and men slightly decrease. In contrast, in countries employing reserved seats for both women and youth (RSRS), young women’s chances are lowest. Party quotas, that usually are candidate quotas and can thus also be conceptualised as nested (PQPQ), are the only institutional configuration where young women’s odds for representation are increased relative to all other groups, and where they have about equal chances as middle-aged to old women. However, since the case numbers in all of those categories are low, multivariate regression analyses to assess the significance and strength of those institutional effects are unfortunately little robust at this point in time.

Case Studies: Gender and Youth Quotas Over Time

To take the analysis one step further, we suggest zooming in on two case studies. We compare the working of legislated candidate quotas in Tunisia and reserved seats in Morocco over time in order to explore when and how HoR changed under different combinations of electoral quotas in both countries. As the dynamics on the party level, especially in the case of voluntarily adopted quotas, may considerably differ, we do not include a case of paired party quotas here.

Legislated Candidate Quotas in Tunisia

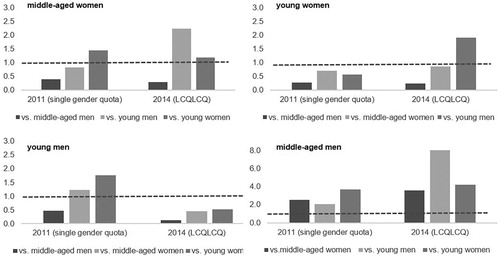

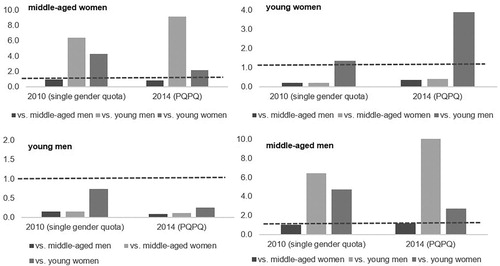

The Tunisian electoral system is based on proportional representation, with closed electoral lists to be voted on in each of the thirty-three constituencies. The first post-revolution election took place in 2011, when the Tunisians elected the Constituent Assembly (CA). A gender quota was already in place, requiring a 50% share and alternating placement for both genders on electoral lists (Charrad & Zarrugh, Citation2014; Debuysere, Citation2016; Gana, Citation2013). The youth quota was introduced in 2014 and applied for the first time in the election of the newly created parliament (Belschner, Citation2018). It requires that at least one person younger than 35 years must be placed in one of the first four list positions. In cases of noncompliance, parties lose 50% of their state funding (République Tunisienne, Citation2014). In terms of mechanisms linking the institution of LCQ to its effects on youth’s descriptive representation, we therefore distinguish between the 2011 election, where a single LCQ for women and no youth quota was in place, and 2014, when two nested quotas regulated the composition of candidate lists. It is striking to compare groups’ odds for representation in 2011 and 2014 ().

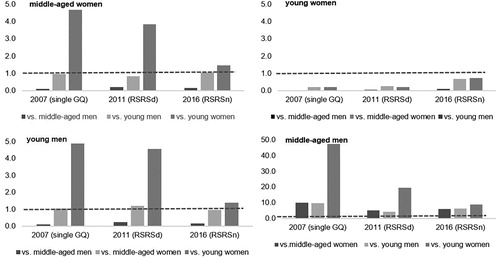

The first plot focuses on middle-aged to old women: In 2011, they had the best chances to be represented compared to young women but fared worse compared to middle-aged to old and young men. In 2014, under a system of paired candidate quotas for women and youth, their chances relative to middle-aged men decreased, while those relative to young men nearly doubled. The next plot shows young women’s odds for representation: While these were very low compared to all other groups in 2011, the introduction of the paired quota boosted them in particular relative to young men, and slightly compared to middle-aged women. Like for middle-aged women, their chances relative to middle-aged men decreased. Finally, the third plot confirms the tendencies of the first two, namely that young men were the group at the expense of which the paired candidate quotas worked. While young men had a 1:2 chance to be represented relative to middle-aged men, and even better chances than middle-aged women and young women in 2011, their odds dramatically decreased with the introduction of the paired gender and youth quotas. Finally, the fourth plot depicts middle-aged to old men’s odds for election. While their chances to be represented are consistently highest compared to all other groups, the change from a single gender quota to a nested candidate quota has not levelled the playing field but in contrast considerably increased the odds for the already majoritarian group. The most significant increase is relative to young men but also relative to middle-aged women.

The introduction of the youth quota additional to a gender quota in Tunisia had thus three main effects: First, it increased the odds for representation of middle-aged men relative to all other groups. Second, it increased young women’s odds slightly compared to middle-aged women and considerably relative to young men. Third, it dramatically decreased young men’s odds for representation.

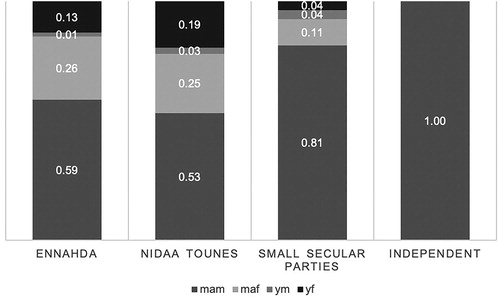

Interestingly, the Tunisian parties seem to have followed a similar logic when implementing the paired quotas. As seen in , small parties have sent considerably less young deputies to the 2014 Tunisian Assembly than the then government parties, the Islamist Ennahda and the secular Nidaa Tounes.

As Belschner (Citation2020) argues in a recent study, this may be due to the fact that all parties alike selected a middle-aged male top candidate for the majority of their lists. Only the parties winning several seats per constituency – mainly Ennahda and Nidaa – would then get candidates further down on their lists, on positions 2, 3, and 4, elected. In contrast, the smaller parties would mostly only get elected one or two candidates per constituency – most often a middle-aged to old men on the first, and a middle-aged woman on the second position.

Reserved Seats in Morocco

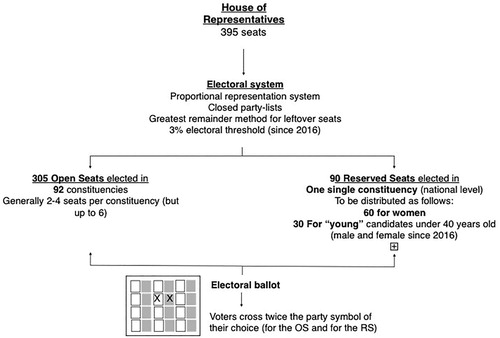

Morocco introduced gender quotas for the first time in 2002, when the political parties agreed to introduce 30 RS for women (of 325 seats) in the lower house of parliament. In 2011, in the context of the Arab Spring, 30 additional RS were adopted for women as well as 30 RS for male youth under 40 years of age. In addition to those 60 additional seats, the total number of seats in the lower house increased to 395. Although Morocco holds multiparty elections with a varying degree of freedom and regularity, ‘the autonomy of the government and the parliament remain subordinated to an executive and legislative monarchy that enables a limited political competition’ (Feliu & Parejo, Citation2013, p. 94). As in Tunisia and Sweden, elections are hold under PR with closed and blocked party-lists.

Since 2011 (see ), the electorate vote for the party of their choice in two different lists: one for the open seats (OS) constituencies (305 seats distributed over 92 constituencies), and the other one for the reserved seats (90 seats in total under one single, national constituency). The results obtained in the RS constituency are then distributed proportionally between the allocated seats for the women and the youth. Since 2016, youth RS are open to women and every party must at least nominate one female candidate in the electoral list. Technically, this transforms the dual quota into a nested one.

How then did the HoR change under the different quota arrangements? So far, research on group representation in Morocco has focused on gender quotas (Darhour & Dahlerup, Citation2013; Sater, Citation2007), largely overlooking the intersectionality between age and gender.

The first plot in focuses on middle-aged to old women. In 2007, with a single gender quota in place, they have the highest odds to be represented. This advantage is slightly reduced by the introduction of an additional RS quota for young men in 2011 (RSRSd), but most considerably with the transformation of the dual quota to a nested RS quota (RSRSn) in 2016. The second plot focusing on young women confirms this tendency. While young women clearly are the most disadvantaged group under all quota systems, their odds have considerably risen by 2016 – especially in comparison to the other underrepresented groups (middle-aged women and young men). The third plot focusing on young men shows that they have, in total, the second-best chances to be represented, although we observe that differences are most pronounced compared to young women. In particular, young men benefited from the dual RS quota in 2011, but this benefit was reduced significantly in 2016. Finally, the fourth plot in the figure confirms that the most privileged group in all legislatures are middle-aged to old men. While they had the highest odds for representation under single gender quotas (2007), the introduction of RS for youth did indeed lower their chances for representation compared to both young men and women, although in 2016 they are still about 8 times more likely to be represented than the latter.

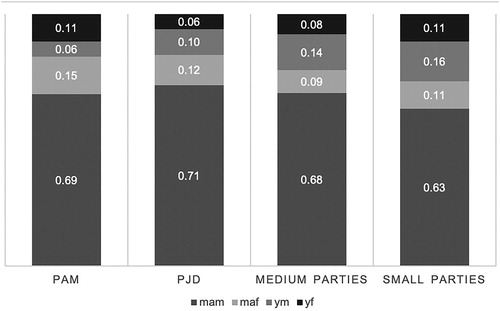

However, it should be noted that the increase of young women’s share in the 2016 parliament is mostly due to the electoral strategy of one party, the Party of Authenticity and Modernity (PAM). This party obtained the second position in the 2016 elections and fulfilled the youth quota with a majority of female candidates, placing the only young male candidate at the bottom of the list. As it is, 7 out of 11 young women MPs were elected on the PAM list.

In general, we do not observe major differences in the gender and age composition between the different parties. This is due to the characteristics of the electoral system and the party system which, due to the small size of the constituencies and the high number of parties, results in the majority of parties only obtaining one or two deputies per constituency, being in their majority men of medium or advanced age. However, some of the variations observed are fundamentally due to the ideological positioning of some parties. On the one hand, small partiesFootnote15 and the secular PAMFootnote16 have a higher proportion of young people and women, while at the opposite pole the moderate Islamist PJDFootnote17 and the ideologically centre-right medium sized partiesFootnote18 are characterised by a higher representation of middle-aged to old men. .

In summary, young women were less likely to be represented compared to middle-aged to old women and young men under the Moroccan single gender quota (RS before 2011) as well as under the dual gender and youth quotas (RSRSd before 2016). The double jeopardy hypothesis is thus confirmed. However, after the establishment of nested gender and youth quotas in 2016 (RSRSn), we observe that young women profit from multiple advantages and increase their odds for representation compared to middle-aged to old women and young men. Throughout all situations, the dominance of middle-aged to old men in parliament is however maintained.

Discussion and Conclusion

In a worldwide perspective, both youth and women are considerably underrepresented in politics. In order to study systematically how paired electoral quotas re-distribute seats between intersectional groups, we suggested the concept of hierarchies of representation, HoR. Recognising that group representation is a relative rather than absolute as well as a dynamic concept and building on Hughes (Citation2011), we defined HoR as one group’s odds for representation in relation to other groups. This allowed us to compare gender and age groups’ changing chances for representation both across space, i.e., under different contexts and institutional settings, and over time.

In our empirical analyses, we first set out to explore groups’ odds for representation in different electoral systems worldwide, before studying to what extent paired quotas for women and youth could be a remedy against young women’s political underrepresentation. The findings show that young women are indeed doubly disadvantaged when it comes to their descriptive representation in parliaments. Although their odds for representation relative to other groups vary dependent on electoral systems, world regions, and quota systems, they are mostly still far from competing on equal terms with middle-aged to old men, middle-aged to old women, and young men.

In the comparative case study of Tunisia and Morocco, we then attempted to trace the re-distributive effects of different combinations of electoral quotas. Based on the existing literature on intersectionality in political representation, we first hypothesised that single gender quotas would privilege the election of middle-aged women over young women (H1), leaving the latter doubly jeopardised. This hypothesis was confirmed in both case studies, with middle-aged women’s odds for election being 5 (Morocco) to 1,5 (Tunisia) times higher than the ones of young women under single gender quotas.

Additional to existing gender quotas, both countries had introduced youth quotas in the wake of the Arab Uprisings in 2011. While the age limits and the concrete share of the quotas differed, we here focused on the differentiation of nested vs. dual paired quotas to determine how the quotas would influence the resulting parliamentarian hierarchies. We hypothesised that nested candidate quotas for women and youth (LCQLCQ) would raise young women’s odds for representation relative to those of middle-aged women and young men (H2), thus providing complementarity advantages to those individuals belonging to two marginalised groups at a time. This hypothesis could be partly confirmed in the cases we studied. Indeed, in Tunisia, young women’s chances over middle-aged women slightly increased under the paired quotas compared to elections under single gender quotas. However, they are still less than equal. In contrast, young women’s odds for election increased considerably relative to young men. In Tunisia, young women have had 2 times better chances to be elected than their young male counterparts.

Our third hypothesis assumed that reserved seats for women and youth (RSRS) existed besides each other (dual quotas) and would thus privilege the election of middle-aged women and young men over young women, respectively (H3). This hypothesis was confirmed for the case of Morocco in 2011, where middle-aged women and young men both trumped young women’s chances for election by 4:1. In 2016, the dual reserved seats were transformed to a nested quota, since it is now regulated that parties’ youth lists must include (at least one) candidate from each gender. Now, although young women continue to have the lowest odds for election of all groups, their chances relative to young men and middle-aged women have tripled compared to 2011. Interestingly, and different than in Tunisia, the nested reserved seats quotas for women and youth have even considerably lowered middle-aged men’s odds for representation.

In sum, however, the paired quotas in both cases tended to re-distribute seats among minorities rather than challenge the overrepresented group of middle-aged to old men.Footnote19

The empirical findings in this study thus confirmed hypotheses derived from studies on the intersection of gender and ethnic identity, showing that individuals at the intersection of inequalities can be doubly jeopardised at times, or profit from complementary advantages at others – dependent on context and institutional setting and contingent over time (Htun & Ossa, Citation2013).

The findings have three main implications regarding the effectiveness of electoral quotas in tackling parliamentarian inequalities between majority and minority groups. First, paired quotas are indeed most useful to support doubly underrepresented groups if they are nested – either as paired candidate quotas or in the form of nested reserved seats. Second, policy makers should be aware that parties tend to enact quotas in a manner that will protect majoritarian groups in parliament. Thus, if young women win, young men and, potentially, middle-aged women might lose. Third, the findings should encourage further enquiries into the effect of paired quotas on the substantive and symbolic representation of intersectional groups and the extent to which an increased presence of young women actually leads to their political empowerment.

Data Deposition

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, J.B., upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Download MS Word (22.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their critical, but always constructive and encouraging feedback. Special thanks go to our doctoral supervisors Ragnhild Louise Muriaas and Thierry Desrues, as well to our discussants at the 2019 ECPG conference in Amsterdam.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jana Belschner

Jana Belschner is a PhD candidate at the Institute of Comparative Politics. Her research interests cover political representation, elections, local politics, and political parties. Her PhD dissertation “The Political Inclusion of Youth. Quotas, Parties, and Elections in Democratic and Democratizing States” investigates how quotas, candidate selection, and electoral processes impact on young men and women’s descriptive representation.

Marta Garcia de Paredes

Marta Garcia de Paredes is a pre-doctoral researcher at IESA CSIC, where she is at the end of her doctoral thesis on the political representation of young people in Morocco. She is also participating in a research project on the crisis of representation in North Africa. Through her field work in the Moroccan parliament, her doctoral thesis seeks to explore the relationship between parliamentary elites and political representation in non-democratic contexts, as well as the growing role of young people as political actors on the African continent.

Notes

1 We use 40 as the main cut-off age between young and middle-aged and thus follow the suggestion of the Inter-Parliamentary Union (Citation2018) and the recent literature on youth representation (Joshi, Citation2013; Stockemer & Sundström, Citation2018). The lower threshold of 20 years is intended to separate young adults with voting rights from children and youth without voting rights. Please also refer to section two for a detailed discussion of age cut-offs.

2 Although it is arguably best suited for the intersectional analysis of dichotomous groups.

3 We also provide an additional case study of paired party quotas in Sweden in the appendix to this article.

4 Hughes speaks of odds for election. We differentiate between the odds for representation when referring to the whole population, i.e., the state level, and of odds for election when referring to electoral candidates, i.e., the party level.

5 The downside is that the odds ratio – in contrast to a QCA based method – cannot explain any representational dynamics, but simply describe it. This is however exactly the purpose of this article.

6 If one wants to compare all group combinations to each other, a three-level age variable would result in 15 instead of 6 comparisons.

7 Which means that the gender quota is not applied to the reserved ethnic seats, nor is the ethnic quota applied to the reserved women seats.

8 With the exception of the Moroccan youth quota since 2016, when 1 seat (out of 30) of the youth quota was reserved for young women.

9 Youth in population is defined within the same age span, 20 to 39, as youth in parliaments.

10 The QAROT (Quota Adoption and Reform Over Time) dataset provides detailed information about quota designs and their development over time worldwide. In particular, it includes a variable (0/1) if a country has an “effective” gender quota, thus setting a higher bar than the simple existence of a law. A gender quota is coded as effective if it includes strong placement mandates and/or strong sanctions (for LCQ), or a strong reserved seat quota (one that specifies some mechanism to fill the reserved seats and that reserves at least 10% of seats for the targeted group) (Hughes et al., Citation2019, p. 11).

11 We also provide an analysis over time of paired party quotas (PQPQ) in Sweden in the appendix of this article. We here modify our method and define the reference group as the share of groups among candidates. The results corroborate our findings about the working of paired legislated candidate quotas in Tunisia.

12 We did not include a case of the LCQPQ form (legislated gender quota and party youth quota), since that would involve different levels of analysis.

13 Only the difference between PR and MP system is statistically significant to p < 0.01.

14 Differences of means statistically significant to p < 0.01.

15 The small parties (less than 15 deputies) come mainly from the secular left (PPS, PGV, PSU). They represent only 5% of the total number of seats.

16 This party was created by personalities close to the palace to counteract the electoral advance of the PJD - moderate Islamist - through a feminist and secular discourse. The PAM concentrates 26% of the seats in the current legislature.

17 With 31.6% of the total seats, it is the first party in the lower house.

18 With between 15 and 40 representatives, these parties are mainly centre-right (PI, RNI, MP) and represent 37% of the total number of seats.

19 Interestingly, we found this effect in our case study of paired candidate quotas in the Swedish Social Democratic Party as well (see appendix).

References

- Belschner, J. (2018). The adoption of youth quotas after the Arab Uprisings. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 1–19. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/21565503.2018.1528163.

- Belschner, J. (2020). Empowering young women? Gender and youth quotas in Tunisia. In H. Darhour & D. Dahlerup (Eds.), Double-edged politics on women’s rights in the MENA region (pp. 257–278). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bird, K. (2014). Ethnic quotas and ethnic representation worldwide. International Political Science Review, 35(1), 12–26. doi: 10.1177/0192512113507798

- Bird, K. (2016). Intersections of exclusion: The institutional dynamics of combined gender and ethnic quota systems. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 4(2), 284–306. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2015.1053399

- Black, J. H. (2000). Entering the political elite in Canada: The case of minority women as parliamentary candidates and MPs*. Canadian Review of Sociology, 37(2), 143–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-618X.2000.tb01262.x

- Bland, J. M., & Altman, D. G. (2000). Statistics Notes: The odds ratio. BMJ, 320(7247), 1468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7247.1468

- Celis, K., & Erzeel, S. (2017). The complementarity advantage: Parties, representativeness and newcomers’ Access to power. Parliamentary Affairs, 70(1), 43–61. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsv043

- Charrad, M., & Zarrugh, A. (2014). Equal or complementary? Women in the New Tunisian constitution after the Arab spring. The Journal of North African Studies, 19(2), 230–243. doi: 10.1080/13629387.2013.857276

- Childs, S., & Hughes, M. M. (2018). ‘Which Men?’ How an intersectional perspective on men and masculinities helps explain women’s political underrepresentation. Politics & Gender, 14(2), 282–287. doi: 10.1017/S1743923X1800017X

- Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785–810. doi: 10.1086/669608

- Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality: Key concepts. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Dahlerup, D. (2008). Gender quotas – Controversial but trendy. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 10(3), 322–328. doi: 10.1080/14616740802185643

- Darhour, H., & Dahlerup, D. (2013). Sustainable representation of women through gender quotas: A decade’s experience in Morocco. Women’s Studies International Forum, 41(2), 132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2013.04.008

- Debuysere, L. (2016). Tunisian women at the crossroads: Antagonism and agonism between secular and Islamist women’s rights movements in Tunisia. Mediterranean Politics, 21(2), 226–245. doi: 10.1080/13629395.2015.1092292

- Erikson, J., & Josefsson, C. (2019). Equal playing field? On the intersection between gender and being young in the Swedish parliament. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 1–20. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/21565503.2018.1564055.

- Evans, E. (2016). Diversity matters: Intersectionality and women’s representation in the USA and UK. Parliamentary Affairs, 69(3), 569–585. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsv063

- Feliu, L., & Parejo, A. (2013). Morocco: The Reinvention of an authoritarian system. In F. I. Brichs (Ed.), Political regimes in the Arab world: society and the exercise of power (pp. 70–99). London: Routledge.

- Franceschet, S., Krook, M. L., & Piscopo, J. M. (2012). Conceptualizing the impact of gender quotas. In S. Franceschet, M. L. Krook, & J. M. Piscopo (Eds.), The impact of gender quotas (pp. 3–26). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Freidenvall, L. (2016). Intersectionality and candidate selection in Sweden. Politics, 36(4), 355–363. doi: 10.1177/0263395715621931

- Gana, N. (2013). Making of the Tunisian revolution: Contexts, architects, prospects. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Hancock, A.-M. (2007). When multiplication doesn’t equal quick addition: Examining intersectionality as a research paradigm. Perspectives on Politics, 5(01), 63–79. doi: 10.1017/S1537592707070065

- Htun, M. (2004). Is gender like ethnicity? The political representation of identity groups. Perspectives on Politics, 2(03), 439–458. doi: 10.1017/S1537592704040241

- Htun, M. (2016). Inclusion without representation in Latin America: Gender quotas and ethnic reservations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Htun, M., & Ossa, J. P. (2013). Political inclusion of marginalized groups: Indigenous reservations and gender parity in Bolivia. politics. Groups and Identities, 1(1), 4–25. doi: 10.1080/21565503.2012.757443

- Hughes, M. M. (2011). Intersectionality, quotas, and minority women’s political representation worldwide. American Political Science Review, 105(03), 604–620. doi: 10.1017/S0003055411000293

- Hughes, M. M. (2016). Electoral systems and the legislative representation of Muslim ethnic minority women in the West, 2000–2010. Parliamentary Affairs, 69(3), 548–568. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsv062

- Hughes, M. M., Paxton, P., Clayton, A. P., & Zetterberg, P. (2019). Global gender quota adoption, implementation, and reform. Comparative Politics, 51(2), 219–238. doi: 10.5129/001041519X15647434969795

- International IDEA. Electoral System Design Database. https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/electoral-system-design.

- Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2014). Youth participation in national parliaments 2014. Geneva: Inter-Parliamentary Union.

- Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2016). Youth participation in national parliaments 2016. Geneva: Inter-Parliamentary Union.

- Inter-Parliamentary Union. (2018). Youth participation in national parliaments: 2018. Geneva: Inter-Parliamentary Union.

- Joshi, D. (2013). The representation of younger age cohorts in Asian parliaments: Do electoral systems make a difference? Representation, 49(1), 1–16. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2013.775960

- Joshi, D. (2015). The inclusion of excluded Majorities in South Asian parliaments: Women, youth, and the working class. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 50(2), 223–238. doi: 10.1177/0021909614521414

- Joshi, D., & Och, M. (2014). Talking about my generation and class? Unpacking the descriptive representation of women in Asian parliaments. Women’s Studies International Forum, 47(November), 168–179. doi: 10.1016/j.wsif.2014.06.004

- Krook, M. L. (2014). Electoral gender quotas: A conceptual analysis. Comparative Political Studies, 47(9), 1268–1293. doi: 10.1177/0010414013495359

- Lilliefeldt, E. (2012). Party and gender in Western Europe revisited: A fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis of gender-balanced parliamentary parties. Party Politics, 18(2), 193–214. doi: 10.1177/1354068810380094

- Mügge, L., & Erzeel, S. (2016). Double jeopardy or multiple advantage? Intersectionality and political representation. Parliamentary Affairs, 69(3), 499–511. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsv059

- Mügge, L., Montoya, C., Emejulu, A., & Weldon, S. L. (2018). Intersectionality and the politics of knowledge production. European Journal of Politics and Gender, 1(1), 17–36. doi: 10.1332/251510818X15272520831166

- Randall, V. (2016). Intersecting identities: Old age and gender in local party politics. Parliamentary Affairs, 69(3), 531–547. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsv061

- République Tunisienne. (2014). Loi Électorale de La Tunisie [Electoral Law of Tunisia].

- Sater, J. N. (2007). Changing politics from below? Women parliamentarians in Morocco. Democratization, 14(4), 723–742. doi: 10.1080/13510340701398352

- Schwindt-Bayer, L. (2009). Making quotas work: The effect of gender quota laws on the election of women. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 34(1), 5–28. doi: 10.3162/036298009787500330

- Stockemer, D., & Sundström, A. (2018). Age representation in parliaments: Can institutions pave the way for the young? European Political Science Review, March, 1–24.

- Stockemer, D., & Sundström, A. (2019). Do young female candidates face double barriers or an outgroup advantage? The case of the European parliament. European Journal of Political Research, 58(1), 373–384. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12280

- Tripp, A. M., & Kang, A. (2008). The global impact of quotas: On the fast track to increased female legislative representation. Comparative Political Studies, 41(3), 338–361. doi: 10.1177/0010414006297342

- UNDP. (2013). Enhancing Youth Political Participation throughout the Electoral Cycle. A Good Practice Guide.

- Weldon, L. S. (2008). Intersectionality. In G. Goertz, & A. Mazur (Eds.), Politics, gender, and Concepts: Theory and Methodology (pp. 193–218). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Appendix

This appendix provides an additional case study over the working of gender and youth quotas on the party level. As the Swedish context does however considerably differ from Tunisia and Morocco in terms of context and since comparability of party and legislated quotas is contested, we did not include this case into the main text.

In general, the results confirm the results found in the main analysis, with paired candidate quotas for women and youth having privileged the selection and election of young women over young men in the Swedish Social Democratic Party.

Party Quotas in the Swedish Social Democratic Party

Sweden employs a PR electoral system with closed party lists elected in 29 constituencies. Unlike Tunisia and Morocco, Sweden does not employ any legislated electoral quotas. However, the share of both women and youth in parliament is among the highest worldwide. Women today make up 43% of all MPs, and an impressive share of 34% are younger than 40 years old.

The Social Democrats (Socialdemokraterna) are historically the dominant party in Sweden and hold a relative majority of 100 seats (out of 349) in the current parliament (elected from 2018 to 2022). The party has employed an internal 50% gender candidate quota since 1993. In 2012, as a run-up to the elections in 2014, the party additionally introduced an internal 25% youth quota for their candidate lists.Footnote20 While it was initially thought to apply to those under 35 years of age, the party constitution does not set a formal cut-off age, and party selectors even speak of a 50% quota for those aged under 40 (Freidenvall, Citation2016, p. 362).

To assess the impact of the youth quota on candidate selection, we therefore suggest calculating groups’ odds for election in the Social Democratic Party for candidates younger than 30 years. Lowering the cut-off age makes sure that those young candidates are truly ‘quota candidates’, and also takes into consideration the lower age average among the Swedish MPs. Furthermore, since we analyse quotas’ impact on the party level, we suggest calculating the odds ratio not based on groups’ shares in population but on their shares among candidates. This allows for a more specific analysis, since it focuses on those aspiring to be elected to parliament.

Figure A.1 thus compares groups’ odds for election, accounting for their share among candidates in the Social Democratic Party for the elections in 2010 and 2014. While the first were still held under a single gender candidate quota, the latter were hold under nested gender and youth quotas.

The first plot in the figure focuses on middle-aged women. Their odds for election were comfortable under the single gender quota, with nearly equal chances relative to middle-aged men. The introduction of the youth quota further increased their chances relative to young men but decreased them slightly relative to middle-aged men and considerably relative to young women. Young women’s odds for election, as visualised in the second plot, were increased relative to all other groups with the introduction of a youth quota. In 2014, the chances of a young female candidate to be elected to parliament were 4 times higher than those of young male candidates; while both groups had had about equal chances in the 2010 elections. This could be a hint that parties strategically placed young women on better list positions than young men, since they fulfilled both the gender and the youth quota at the same time (therefore, the youth quota also reduced the chances of middle-aged women relative to young women). Those results are in line with the findings of previous studies on candidate selection processes in Sweden. While most parties in Freidenvall’s study agreed that gender and age are very important or important criteria for candidate selection, the Social Democratic selectors stressed the double quota regulations as guiding principles (Freidenvall, Citation2016, pp. 360–62). The third plot confirms the tendency of the first second, with young male Social Democratic candidates having the worst chances to be elected relative to the other groups. Unlike as in the other cases, though, some of young women’s higher chances for success were taken from middle-aged male candidates. In the 2014 elections, young women’s chances relative to middle-aged men slightly increased. However, so did middle-aged men’s relative to middle-aged women and young men.

In summary, middle-aged women candidates were most privileged in the 2010 elections, under a single gender quota. Young women candidates were the biggest profiteers of the double quotas in 2014. The increase in their odds for election was for the most part due to a reduction of young men’s chances, as well as middle-aged women’s. As in Tunisia, paired candidate quotas most considerably decreased young men’s chances to be elected relative to all other groups. In contrast, and counter-intuitively, paired quotas for women and youth did not substantially decrease middle-aged male candidates’ odds for election.