ABSTRACT

This article examines the use of a Citizens’ Jury as a source of voter information in the context of a government-initiated (top-down) referendum. Several studies show the capacity of the Citizens’ Initiative Review (CIR) to enhance voters’ knowledge and capacity of judgement in ballot initiative processes. However, similar procedures have not been tested outside the U.S.A. or in the context of government-initiated referendums. Our case is a Citizens’ Jury on Referendum Options organised in the municipality of Korsholm (Finland) in 2019. Even though the referendum concerned a contested municipal merger, we find that jury's participants were nonetheless satisfied with the deliberative process and found it impartial. A large majority of voters in Korsholm had read the statement by the jury and thought it was a useful and trustworthy source of information. Based on a field experiment, we find that reading the statement increased trust in the jury, factual knowledge, issue efficacy and perspective-taking.

Introduction

Most modern democracies include elements of direct democracy, usually in the form of referendums. While referendums aim to capture the collective will of the people by giving each voter an equal say on an issue (Tierney, Citation2012, p. 19), the problems of referendums are rather obvious, as highlighted by the UK Brexit referendum. Referendums are prone to manipulation by the elite (Lijphart, Citation1984; see also Qvortrup, Citation2017), and to the use of partisan cues and shortcuts (LeDuc, Citation2002; Suiter & Reidy, Citation2013). Consequently, referendum campaigns are often devoid of meaningful deliberation (Chambers, Citation2001; LeDuc, Citation2015).

In order to address such problems, there have been calls for measures enhancing public deliberation in conjunction with referendums and other direct democratic procedures. For example, Barber (Citation1984) suggested that initiatives and referendums should always be combined with procedures such as town hall meetings that enhance citizen deliberation and reflection on the issue at hand. Ackerman and Fishkin (Citation2002) have recommended that there should be a specific public holiday, a so-called ‘deliberation day’, before every national referendum.

In this article, we study a particular mechanism of linking public deliberation with popular votes (Gastil & Richards, Citation2013). Institutionalised in Oregon, the Citizens’ Initiative Review (CIR) entails a Citizens’ Jury in which a group of randomly selected citizens deliberate and assess information concerning an initiative before it is put to the ballot. The aim of the jury is to provide reliable and relevant information in order to help voters make decisions on ballot initiatives. Previous studies (see, e.g., Már & Gastil, Citation2020; Knobloch, Barthel, & Gastil, Citation2019) have shown that a CIR offers some remedies to problems of popular votes by enhancing voters’ knowledge and capacity of judgement.

The CIR was designed to address problems of ballot initiatives in the U.S.A. In this article, we examine whether the CIR model can help voters to make informed and reflected judgements in a very different institutional, political and cultural context. The Citizens’ Jury on Referendum Options in Korsholm, Finland, followed the CIR model by convening a jury to deliberate the pros and cons of the issue at hand, that is, a municipal merger. The jury came up with a written statement that was sent to all voters in Korsholm before the referendum.

The Citizens’ Jury in Korsholm differs from the CIR process at least in three important respects. First, the referendum in Korsholm was an advisory referendum initiated by the municipal council. In this respect, it belongs to the category of ‘top-down’, that is, government-initiated referendums, which are used at various levels of governance in several European democracies (e.g., Morel, Citation2001). Second, unlike in the U.S.A., Finland does not have a tradition of randomly selected court juries, which means that citizens are not accustomed to jury work nor the institution of Citizens’ Juries. Third, the referendum pertained to a complex and polarising proposal for a municipal merger, whereas CIRs in the U.S.A. have usually involved more mundane policy issues that are less likely to create lasting divisions in society.

All this entails that the Citizens’ Jury on Referendum Options in Korsholm provides a hard test for the CIR model. We are particularly interested in the quality of the deliberative process, public awareness of the Citizens’ Jury and its statement, as well as the impact of the statement on the public in Korsholm. By testing the CIR procedure on this critical case, we can assess whether the model can be used to address the problems of referendums more generally. In this way, our study also contributes to the discussion on the prospects of democratic deliberation in the context of mass participation (Chambers, Citation2009).

Our study uses three different sources of data, that is, a survey among the participants of jury, a post-referendum survey among a representative sample of voters in Korsholm, and a field experiment examining the effects of reading the statement. Our results indicate that the Citizens’ Jury on Referendum Options constituted a deliberative complement to the referendum campaign. The jury and its statement received a great deal of public attention. The results also suggest that reading the jury's statement increased voters’ trust in the jury. Even more importantly, reading the statement helped voters make their decisions in the referendum by increasing their factual knowledge, their issue efficacy and perspective-taking.

The CIR as a Potential Remedy to the Problems of Direct Democracy

The Problem of Voter Choice in Different Forms of Direct Democracy

One of the key problems of all referendums or popular votes seems to be a low level of voter knowledge. Following Downs’ argument of ‘rational ignorance’ (Citation1957), because an individual vote is unlikely to affect the outcome of a referendum, people are rarely motivated to delve deep into the issue at hand. Therefore, voters do not necessarily learn much during referendum campaigns, and their understanding of the likely consequences of the proposed measures remains limited (Tierney, Citation2012, pp. 27–28).

The main point of referendum campaigns is to win votes by mobilising as many voters as possible, rather than engaging in serious deliberation on the pros and cons of the different alternatives (Chambers, Citation2001). Just as in elections, voters in referendums also encounter public discourse through various media sources. This stream of information is, however, often characterised by strategic campaigning, filled with manipulation and scaremongering. For this reason, referendums have been seen to exacerbate intergroup tension, polarise the public opinion and even divide societies (Ford & Goodwin, Citation2017; Stojanovic, Citation2006). In this respect, it seems appropriate to ask whether the use of referendums can be compatible with the idea of deliberative democracy in the first place (LeDuc, Citation2015).

There are some differences with different types of popular votes, however. Originally, the Citizens’ Initiative Review was developed to facilitate voters’ knowledge and judgement in the context of the ballot initiative processes in Oregon. In the U.S.A., ballot initiatives were originally introduced by the Progressive Movement in order to decrease the powers of special interest groups and allow grass-roots civic activity (Smith, Citation2002, pp. 892–893). Although citizens’ initiatives provide channels of influence for otherwise underrepresented groups (Boehmke, Citation2005), money and special interests are crucial for initiatives to gather enough signatures and to be passed in popular votes (Reilly & Yonk, Citation2012, p. 5).

While the CIR was designed to address these types of problems, we are interested in the use of CIR-type procedures in the context of government-initiated or ‘top-down’ referendums. In many European democracies, including Finland, elected representatives control the use of referendums (Setälä, Citation2006). The problem with these types of referendums is that they are often used strategically by political elites rather than out of genuine interest in improving the quality of democracy. Political elites’ motivations to use these types of referendums may have to do with electoral calculations or divisions within governing parties (Morel, Citation2001).

Empirical literature on voter choice shows that voters often rely on partisan cues and other shortcuts that shape information-processing and opinion-formation (Lupia & McCubbins, Citation1998; Gastil, Citation2014; Leeper & Slothuus, Citation2014). Especially in the case of ‘top-down’ referendums, public debate is likely to be dominated by partisan political actors, and voters are likely to follow cues from those partisan actors that they can identify with. However, in case of ‘top-down’ referendums, divisions within parties may complicate voters’ choices. (LeDuc, Citation2002). All of this suggests that it can be difficult for voters to find trustworthy sources on information to learn more about referendum topics, which means it is hard for them to cast an informed vote.

The CIR as a Trusted Source of Information

There are various practices of providing voters with reliable information before referendums and popular votes. Ireland has an independent Referendum Commission that is expected to inform voters about the referendum proposals (e.g., Suiter & Reidy Citation2013). Based on a parliamentary debate, the Swiss national government issues voter recommendations on each issue submitted to a popular vote (Lutz, Citation2006). While a governmental voter recommendation may appear to be a reliable source of information in Switzerland where all major parties are included in a government, it would probably not work in most representative democracies with a government-opposition divide.

The idea of the Citizens’ Initiative Review (CIR) is to address the problems of ballot initiatives such as adversarial campaigning, voter ignorance and the influence of moneyed interest groups (Gastil & Knobloch, Citation2020, p. 6). Since 2010, the CIR has been regulated in the Oregon State Law. The CIR is organised by the non-governmental organisation Healthy Democracy under the direction of the Oregon CIR Commission. Similar CIR processes have recently been piloted in other US states, such as in Arizona, Colorado and Massachusetts (Healthy Democracy Citation2020).

The CIR Citizens’ Jury consists of a group of 18–24 registered Oregon voters, selected through a stratified random sample. Convening on four consecutive days, the jury is tasked to evaluate information regarding a ballot initiative with the aim of helping citizens make an informed and reflected decision (Warren & Gastil, Citation2015, p. 569). The Citizens’ Jury hears advocates from both sides of the issue as well as independent experts as witnesses. Based on its deliberations and information gathered, the jury evaluates and develops factual arguments related to the ballot measure as well as arguments for and against it. The most important arguments are summarised in a one-page statement consisting of a description of the jury, its key findings, and the three most important arguments for and against the initiative. The statement is included as a part of official Oregon State Voter's Pamphlet, which is delivered to all registered voters (Warren & Gastil, Citation2015, p. 570).

Previous studies on the CIR show that it is well-designed deliberative process allowing a thorough and even-handed examination of the pros and cons of a ballot initiative. Participants of the jury process have been generally speaking highly satisfied with the deliberative quality, facilitation and analytic rigour of the process (Gastil & Knobloch, Citation2010; Gastil, Broghammer, Rountree, & Burkhalter, Citation2019). An analysis by Knobloch, Gastil, Reedy, and Walsh (Citation2013; see also Gastil & Knobloch, Citation2010) shows that the jury process enables building of a solid information base and that participants of the jury learn a great deal about the subject at hand. Participants also become more confident about their ability to make an informed decision about the issue. These studies also found notable shifts in participants’ opinions during the CIR, which is not an intrinsic goal of deliberation, but still shows that non-coercive opinion change can take place.

However, the primary purpose of the CIR is to provide relevant and reliable information for other voters. A precondition for this is that the statement of the Citizens’ Jury is distributed to all voters, who read it and find it a trustworthy source of information. The fact that the CIR statement is formulated by fellow citizens, not by politicians or experts, seems to be an important factor when it comes to how it is received in the electorate. As Gastil (Citation2014, p. 157) argues, the evidence on the CIR shows that ‘[…] voters appreciate hearing concise issue summaries from their peers’.

One could argue that CIR statements are just another cue or shortcut for voters. For example, Ingham and Levin (Citation2018) have examined the signalling effects of mini-publics in the presence of partisan cues. Their study shows that the signal from a mini-public predominantly influences independents who are less likely to follow partisan cues. However, their study assumes that mini-publics signal opinions on the proposed ballot measure. While the CIR reports used to include a majority opinion on the ballot measure, this is no longer the case. In this respect, CIR-type mini-publics are clearly different from partisan cues.

Moreover, Warren and Gastil (Citation2015) argue that voters’ trust in mini-publics is different from trust in elected representatives based on party identifications. Trust in mini-publics is ‘facilitative’ in the sense that it helps learning and deliberation among voters. In other words, reading a statement by a CIR jury helps lower voters’ cognitive costs of making political judgements, while not reducing their capacity of critical judgement. Facilitative trust is based on voters’ perception that a mini-public succeeds to deliver reliable and balanced information on the issue at stake (Warren & Gastil, Citation2015).

Previous studies from Oregon show that 42–55 per cent of likely voters reported to have been aware of the CIR, and 29–44 per cent claimed that they had read the Citizens’ Statements (Gastil, Johnson, Han, & Rountree, Citation2017). Surveys conducted in Oregon further indicate that a majority of those who have read CIR statements finds them informative (Gastil & Knobloch, Citation2010; Knobloch, Gastil, Richards, & Feller, Citation2014). Moreover, surveys show that Oregon voters put more trust in the quality of judgements of CIRs than the state legislature, and as much as in impartial bodies such as courts (Warren & Gastil, Citation2015, pp. 570–571).

Reading the CIR statement seems to help voters make better informed and reflected decisions on ballot initiatives. A recent study by Knobloch et al. (Citation2019) finds that reading the CIR statement increases voters’ political self-confidence, especially initiative-related efficacy. Moreover, the CIR seems actually facilitate critical judgement. Reading CIR statements has led voters to think that they would need to investigate and reflect on the issue more carefully (Warren & Gastil, Citation2015, p. 570). Studies also indicate reading the CIR statement can increase factual knowledge (Gastil, Knobloch, Reedy, Henkels, & Cramer, Citation2018; Gastil & Knobloch, Citation2010) and even counteract effects of motivated reasoning (Már & Gastil, Citation2020). CIR-type processes also have a capacity to trigger reflection on facts as well as pros and cons of policy options, including arguments that seem to be supportive of ‘the other side’ (cf. Suiter, Muradova, Gastil, & Farrell, Citation2020).

Citizens’ Jury on Referendum Options in Korsholm

The Context: Referendum on Municipal Merger in Korsholm

Referendums are rare events in Finnish politics at the national level as there have only been two advisory referendums initiated by the Finnish Parliament. More referendums have been held at the municipal level. These referendums are also formally advisory and ‘top-down’, meaning that the decision to hold a referendum is made by elected representatives, who also make the final decision on the issue. There is also an opportunity for the residents of the municipality to make a motion for the municipal council to organise an advisory referendum on a particular issue, but, even in this case, the municipal council decides whether a referendum is to be held or not. Most municipal referendums have dealt with plans for a merger with another municipality, although it is not mandatory to organise a referendum on a municipal merger (Jäske, Citation2017)

Korsholm is a municipality on the west coast of Finland with a population of around 19,000 inhabitants. A majority of residents are Swedish speaking (around 70% of the population compared to about 5% in the general population), while around 30 per cent are native Finnish speakers. The prospect of a merger between Korsholm and the neighbouring city of Vaasa has been debated for decades. In 2017, the municipal authorities of Korsholm and Vaasa began negotiations on a merger agreement, which were completed in January 2019. The municipal council of Korsholm decided to organise a consultative referendum on the merger agreement in March of the same year. The merger issue was not equally salient in Vaasa, and there was never any intention to organise a referendum on the merger in the city.

The Korsholm referendum provided an opportunity to test whether the CIR model could facilitate voter knowledge and judgement in the context of a ‘top-down’ referendum on the contested and complex issue of a municipal merger. A bilingual team of researchers from the University of Turku and Åbo Akademi University were responsible for designing the Citizens’ Jury process and implementing it, from the recruitment of participants to the mailing of jury's statement to all voters. The authorities of Korsholm and Vaasa were not involved in the organisation of the jury, except for providing the town hall facilities in Korsholm for jury meetings. This approach was chosen in order to ensure the impartiality of the process. At the same time, it also meant that the jury did not have an official status in the referendum process.

In addition to potential impacts on people's everyday lives, municipal mergers often become issues of identity (see Zimmerbauer & Paasi, Citation2013). This was also the case in Korsholm, where the debate on the referendum became polarised over several issues. A rural/urban divide became a focal point in the debate since there were concerns over the effects on the rural identity of Korsholm as opposed to the urban way of living in the city of Vaasa. Language was also important since the Swedish-speaking majority in Korsholm would become a minority in a merged municipality. The Finnish-speaking minority in Korsholm and those living near Vaasa were more positive towards the merger (see Strandberg & Lindell, Citation2020). In addition to these issues, concerns about local democracy, municipal service provision and the long-term viability of the local economy were also raised in public debate. Public debate on the merger was hot-tempered and even led to harassment and threats (Yle News Citation2019).

As pointed out earlier, the case of Korsholm was thus a hard test for the CIR method. While previous CIR juries have discussed controversial topics such as GMO farming, casinos, criminal sentences and marijuana (Healthy Democracy, Citation2020), the CIR has not up to date been used for identity politics where the results may create long-lasting divisions in society. As the experience of EU referendums shows, identity questions can lead to high levels of affective polarisation where people define their political identity based on their issue position (Hobolt et al., Citation2020).

Compared to CIR processes in the US, the Citizens’ Jury in Korsholm had some distinctive organisational characteristics. First, while all CIR processes in the US have been held in English only, the Citizens’ Jury in Korsholm was bilingual. In order not to exclude either of the language groups, the jury was prepared so that each participant could use their own mother tongue. Materials were prepared in Swedish and in Finnish, and all moderators were bilingual. Participants could use either language and interpretation was provided when needed. The jury's final statement was also written in both languages.

Second, while the CIR juries have been open to the public and the media, the Citizens’ Jury in Korsholm was conducted mostly behind closed doors. This was because of the risk of social pressures on jury members, given the small size of the community and the high polarisation of the merger issue. The organisers ensured the transparency of the processes of participant recruitment and jury deliberation, but the public and the media could follow only the advocate and expert hearings. Third, in order to help people working on weekdays to participate in the jury, the Korsholm jury convened over two consecutive weekends and not four consecutive days like the CIR.

Recruitment and the Composition of the Citizens’ Jury

The project began with a recruitment survey mailed to a random sample of 1400 adult residents in Korsholm. In this survey, respondents could indicate whether they were willing to participate in the Citizens’ Jury. The respondents were also informed about the compensation of €500 for participants. The response rate to the survey was 23 per cent (n = 320), and 23 per cent of those who answered (n = 73) volunteered to take part in the jury. From this group of volunteers, a demographically diverse jury was formed. The aim was to compose a jury that would represent the population of Korsholm in terms of language, place of residence, gender, and age. In addition, the jury should be balanced in terms of merger attitudes (there was a slight overrepresentation of people in favour of the merger in the final jury). Of the 24 volunteers selected to take part, 21 showed up, and these individuals constituted the Citizens’ Jury on Referendum Options. Basic information regarding the composition of the jury is presented in .

Table 1. Jury composition.

The program of the Korsholm Citizens’ Jury followed the CIR model rather closely, but minor adjustments were made due to the bilingual nature of the jury. During the first day, the jury familiarised with local referendums and municipal mergers as well as with the working principles of the jury. Participants learned about the rules and norms of deliberation, and exercised evaluation of information by its reliability and relevance. The day ended with opening addresses by advocates from both sides, that is, local politicians supporting and opposing the merger. During the second day, participants gathered evidence by questioning advocates and several neutral experts. Based on the information they had received, participants started to draft potential claims to be included in the statement.

During the third day, participants developed and assessed various merger-related claims in order to provide relevant and reliable information to other voters. During the last day, the most reliable and relevant claims were selected and assigned into different sections of the statement, that is, the key facts and the most important claims for and against the merger. Specific language committees corrected the different language versions and ensured that both languages versions of the statement were identical. Finally, the jury approved the statement unanimously. Following the most recent version of the CIR process, the final statement did not report the jury members’ position on the merger issue. After a research period of one week, the statement was sent to all voters in Korsholm and published online. The English translation of the statement can be found in Appendix 2.

While the Korsholm Jury followed the CIR manual, the multidimensionality of the merger issue proved to be challenging during the jury process. The participants spent much of the time discussing the potential consequences of the merger on the status of the region in Finland, local democracy, municipal service provisions, local economy, linguistic rights and identity. Despite participants having strong and polarised views on these issues, the CIR process ensured that the discussions were respectful and constructive. Furthermore, largely thanks to the participants’ skills and motivation to work in two languages, it was possible carry out the deliberations and write the statement in two languages simultaneously.

The jury process gained quite a lot of attention in the media. It was covered about 30 times in the news media, most often in local newspapers. The media coverage largely focused on the issues brought up in the press releases by the organisers, such as the procedures applied in recruitment and in jury deliberations. The statement by the jury was published in a press conference where four volunteers from the jury read the statement in both Swedish and Finnish. The statement was also covered in the local media, and the locally dominant Swedish-speaking newspaper published the whole statement. While the media attention mostly followed the organisers’ press releases, there were also some critical reports on the process. There were doubts whether it was possible for Finnish-speaking participants to fully participate in the jury dominated by Swedish-speakers (Pohjalainen, Citation2019). Moreover, questions were raised about some participants’ close ties with the pro campaign (Vasabladet, Citation2019).

The consultative referendum concerning the merger plan was held on March 17. The result was that a clear majority of the voters, 61.3 per cent, rejected the merger. The turnout in the referendum was 76.4 per cent. After the referendum (April 2), the municipal council decided to reject the merger. summarises the timeline of the key events and the collection of data.

Table 2. Procedure and timeline: Citizens’ Jury on referendum options in Korsholm.

Research Questions and Empirical Study Design

In this article, we are interested in three aspects of the Citizens’ Jury process. First, we assess the deliberative quality of the Citizens’ Jury by examining whether the participants perceived that jury process was successful in dealing with the merger issue in a thoroughly and even-handedly. Second, we examine the public reach of the jury's statement by analysing the extent to which voters had heard about the jury and actually read the statement. Third, we examine the effects of reading the statement, most importantly, whether reading the statement helped voters make more informed and reflected decisions on how to vote.

To assess the first aspect, we rely on 4 surveys that the 21 participants filled in the end of each of the 4 days of the jury. These surveys were conducted to get feedback from the participants regarding the jury procedure and to monitor learning, opinion shifts and evolution of perspective-taking, among others. All 21 participants answered all the surveys. While the CIR process is a result of years of research and development, this data provides information on participants’ experiences in the case of Korsholm. We examine the evaluations of certain key aspects of the deliberative process: daily assessments of moderators’ work, opportunities to express opinions, and respectfulness of deliberation. We also explore participants’ final evaluations of inclusiveness, impartiality, and the overall quality of jury process.

For the second aspect, we examine whether voters in Korsholm were aware of the jury's existence and had read its statement. We here rely on a post-referendum survey administered to the voting-age population in Korsholm following the referendum (n = 244, response rate 24.4%).Footnote1 We explore the following aspects: whether voters were aware of the jury process, whether they had read the statement, and whether those who had read the statement found that it contained useful information.

In order to examine the third aspect, namely the impact of the jury's statement, we examine whether reading the statement helped increase knowledge, trust, efficacy and perspective-taking among voters. To this end, we make use of a field experiment conducted right after the Citizens’ Jury had concluded its work, but before the statement had been made public. We sent a survey with the statement to a randomly selected treatment group, while a control group only received a survey. Both groups initially included 500 randomly selected respondents. The treatment group was asked to read the statement before answering the questions. The questions in the survey pertained to knowledge about and attitudes toward the merger, views about local politics, views of the jury and the usefulness of the statement. The survey received by the control group included the same questions apart from those concerning the statement. This approach makes it possible to compare differences in responses caused by reading the statement.

Although the surveys conducted among voters suffer from low response rates, the respondents on most accounts resembled the general population, as shown in Appendix 1.Footnote2

The field experiment makes it possible to explore the actual effects of reading the statement compared to deciding with the otherwise available sources of information. Since the treatment and control groups were randomly selected, in principle any difference can be attributed to reading the statement. Here we focus on four central aspects of how reading the jury's statement may plausibly improve the possibilities for the voters to make a considered judgement:

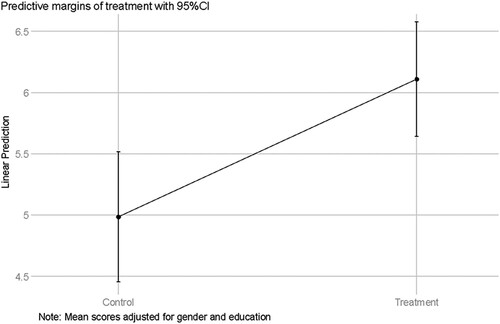

Trust in the Citizens’ Jury: If the Citizens’ Jury managed to issue a statement including reliable and relevant information, reading the statement should make voters more trusting of the jury. To measure this aspect, we use a single item where respondents indicate their level of trust in the Citizens’ Jury on a scale 0–10 (mean = 5.5, SD = 2.4).Footnote3

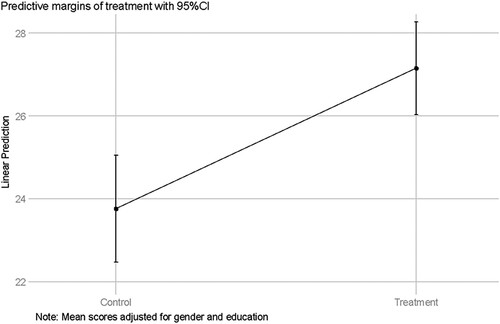

Factual knowledge: Reading the statement should improve voters’ factual knowledge. Our measure of factual knowledge is based on 10 factual questions (Five true and five false, all shown in Appendix 3), where all respondents for each question indicated whether they thought it was ‘definitely not true’, ‘probably not true’, ‘Don't know’, ‘probably true’ or ‘definitely true’. Each question was coded 0 = 'Very certain and wrong’, 1 = 'Somewhat certain and wrong’, 2 = 'Don't know’, 3 = 'Somewhat certain and correct’ and 4 = 'Very certain and correct’. Hence the index simultaneously captures knowledge and certainty, since this is also an important criterion for being able to make judgements based on solid evidence. The combined index varies between 0 and 40 with higher scores indicating truer and more certain knowledge (mean = 25.0, SD = 5.5).Footnote4

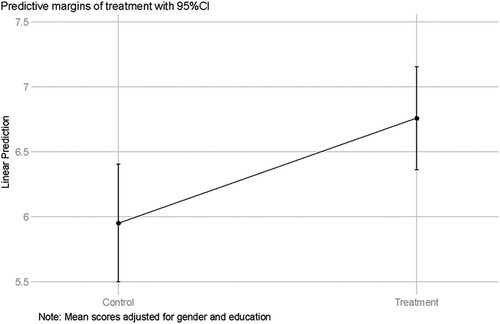

Issue efficacy (the extent which respondents feel capable to comprehend the merger and the issues involved): The statement should give voters a feeling that they are competent to make decision. The measure for this is based on answers to two questions where respondents on 5-point Likert scales indicated (Strongly disagree–Strongly Agree) indicated the extent to which they agreed with a statement on their perceived competence (I think I am competent enough to make a decision regarding the merger between Korsholm and Vaasa) and their perceived understanding of the issues (I have sufficient understanding of all things related to the merger between Korsholm and Vaasa). The index varies between 0 and 8 with 8 indicating stronger efficacy (Mean = 6.3, SD = 1.9).

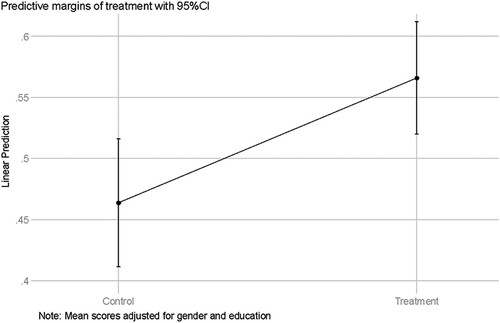

Thinking about others’ perspectives: The statement should make voters think about the issue from different perspectives. To measure this aspect, we use an index constructed based on three questions measuring time spend thinking about other people's perspective when deciding how to vote: 1. How much time did you spend evaluating proposals, values and worries among people who OPPOSE the merger before deciding how to vote? (five categories 0–1, 0 = no time at all, 1 = very much time); 2. How much time did you spend evaluating proposals, values and worries among people who SUPPORT the merger before deciding how to vote? (five categories coded 0–1, 0 = no time at all, 1 = very much time), and 3. How sympathetic were you towards people whose life situation is completely different from yours? (five categories coded 0–1, 0 = not at all, 1 = very much). The index was recoded to vary between 0 and 1 with 1 indicating a higher degree of perspective-taking (Cronbach's alpha = 0.76, mean = 0.50, SD = 0.23).

The methods of analyses depend on the aim. For the first two aspects, we rely on descriptive percentages of experiences and evaluations. For the final aspect of the impact of the statement, we use linear regression analyses to determine differences between the treatment and control group.Footnote5 The results are shown in figures to ease interpretation, but all results are available in Appendix 4.

Results

We start our presentation of the results by an examination of participants’ evaluations of the Citizens’ Jury. provides information on how the participants experienced and evaluated the jury proceedings.

Table 3. Evaluations of the Citizens’ Jury by participants (n = 21).

According to the daily evaluations, the participants generally felt that they had chances to express their views and their views were respected during the jury process. Moderators were also found impartial. There were only few occasions where participants had felt pressures to agree. Open responses by the participants show that the pressures were due to the tight schedule of the jury process; peer pressure was mentioned only once. In addition, final evaluations show that participants felt that they had learned during the process, that diversity of opinions were heard in the jury, and that different views were treated in an impartial manner. In this respect, and despite the challenges described earlier, the deliberative process in the Korsholm jury seemed to have worked well.

The next aspect to be examined is the public awareness of jury process and the extent to which voters had read the statement and found it useful. shows sheds light to the public at large perceived the jury and its statement.

Table 4. Public awareness of Citizens’ Jury and the readership of the statement.

A majority of respondents (59.2 per cent) were somewhat or very aware of the existence of the Citizens’ Jury, which indicates that many had followed the process, e.g., via local media. While 23.1 per cent of respondent claimed they were not very aware of the jury, only 17.6 per cent of respondents were not at all aware of it. Notably, as many as 76.4 per cent of respondents said they had read the statement. Although this result may be somewhat biased because those who had read the statement may have been more likely to respond to the survey, it seems safe to conclude that the jury's statement gained the attention of most voters in Korsholm. Furthermore, we can observe that a clear majority (63%) of those who had read the statement found it useful, and a majority (56%) also felt that they had got new information by reading the statement. 72% of all readers considered the statement to be a trustworthy source of information.

All this shows that the statement of the jury succeeded by most accounts in gaining public attention and providing information that most thought was credible. This is also supported by a mean trust in the Citizens’ Jury score of 5.5 on a scale from 0 to 10. While this score may seem unimpressive in absolute terms, it is only behind trust in independent experts (mean 6.2) and ahead of politicians supporting merger (4.7), civil servants in Korsholm (4.9), local media (5.1) and politicians opposing merger (5.2). This is remarkable considering that the Citizens’ Jury did not have an official status in the process and that this kind of a Citizens’ Jury process had never been used in the Finnish context before.

This still leaves unanswered the third question of whether the Citizens’ Jury had the desired impact, that is, enhancing knowledge and judgement among voters. In what follows, we report how reading the statement affected the public's trust in Citizens’ Jury, knowledge, efficacy and perspective-taking based on the treatment and control survey. The extent to which the Citizens’ Jury has succeeded in its task to provide reliable and relevant information should be reflected in voters’ evaluations of the jury. First, we compare levels of trust in the jury in the treatment and in the control group. shows these results.

The treatment group reports a higher score compared to the control group, the difference being about 1.1 on the 0–10 index (B = 1.13, SE = 0.36, p = 0.002). This suggests that reading the statement increased trust in the Citizens’ Jury, compared to the control group, where respondents did not read the statement. Reading the statement produced a perception of the jury as a trustworthy source of information. Hence, reading the statement may have defused some of the doubts about the Citizens’ Jury process that were raised in the media during the process.

Next, we examine whether reading the statement improved voters’ levels of knowledge about the merger. displays the results.

The results show that respondents on average reported a 3.4 points higher score in the treatment group (B = 3.39, SE = 0.87, p = 0.000), meaning that reading the statement clearly increased factual knowledge about merger-related issues and knowledge certainty among voters.Footnote6

However, increased factual knowledge is not necessarily reflected as an increase in the sense of internal efficacy, understood as confidence of being capable of making an informed choice in the referendum. shows the differences in this regard.

Reading the statement also improved issue efficacy, since people in the treatment group on average report a 0.81 higher score on the 0–8 index (B = 0.81, SE = 0.31, p = 0.010). Hence reading the statement also made people feel more competent to make an informed decision concerning the merger.

According to the theory of deliberative democracy, it is important that voters consider the issue, not just from their own, but also from the perspective of others affected by the decision. This kind of judgement is particularly challenging in case of polarising and divisive issues such as the municipal merger of Korsholm. shows the extent to which reading the statement helped voters to consider the perspectives of those who have different views on the merger.

Again, reading the statement before answering the survey made it more likely that people reported thinking about the issues from the perspectives of those with opposed views. On average, people reading the statement reported a score on the 0–1 index about 0.10 higher than those in the control group (B = 0.10, SE = 0.04, p = 0.005). This shows that reading the statement, including the key facts and arguments from both sides, helped people think more about the perspectives of those with different views before deciding how to vote.

Discussion

The aim of this article was to examine whether the CIR model could also work outside of the U.S.A., in an institutional and political context that differs in several respects from where the process was initially conceived. In addition to assessing whether the CIR can help voters make informed and reflected choices in ‘top-down’ referendums, our case of Korsholm constituted a hard test of the viability of the CIR procedure in a polarised and deeply divided context.

Our results have a number of important implications concerning the viability of the CIR procedure. Based on the day-by-day evaluations and the final feedback given by the 21 participants, the Citizens’ Jury on Referendum Options succeeded in dealing with the various aspects of the merger issue in a thorough and respectful manner. Almost all participants reported that they were satisfied with the impartiality of the process and the diversity of opinions voiced during the four-day deliberations. These findings resemble participant evaluations of the deliberative quality of previous CIRs in the U.S.A. Despite the lack of meaningful discourse, distrust and even hostility between different sides of the issue, the Citizens’ Jury was able to offer a venue where participants were exposed to the arguments of the other side and had a chance to rigorously weigh information and viewpoints. In addition to these important findings, the fact that the Citizens’ Jury was carried out bilingually shows that the process can be adapted without sacrificing the deliberative quality.

The Citizens’ Jury was also warmly welcomed by the general public. Although some reservations regarding the jury were expressed, e.g., in the media, our results generally suggest that there was high awareness of the jury, most voters had read its statement, and a majority of the readers found its information useful. Public awareness in the Korsholm case was actually very high compared to the CIRs conducted in Oregon (Gastil et al., Citation2017). These differences may be due to several reasons, such as the high salience of the merger issue and the extensive coverage of the jury in the media.

Finally, our results also show that reading the statement increased trust in the jury and, most importantly, increased voters’ factual knowledge, their sense of issue efficacy, and made them consider the merger issue from different perspectives. These effects are in line with the findings from CIR processes in the U.S.A. This is remarkable because Korsholm was deeply divided regarding the merger, and opinions were both polarised and segregated.

Our results show CIR-type processes can help provide trustworthy information that help voters make informed and reflected choices in polarised top-down referendums. In addition, CIR-type processes can work even in a context where there is no prior familiarity with a jury system, as is the case in Finland. We can therefore conclude that the CIR model seems to ‘travel’ quite well, and it could be used to address problems of referendums on various issues and in different institutional, political and cultural contexts.

Supplementary Material.docx

Download MS Word (25.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Prof. John Gastil for his assistance in designing the surveys, Healthy Democracy Oregon, especially Mr. Linn Davis, for help in organising the Citizens' Jury, and Ms. Katariina Kulha for superb research assistance.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maija Setälä

Maija Setälä is a Professor in Political Science at the University of Turku, Finland. Setälä specializes in democratic theory, especially theories of deliberative democracy, direct democracy and democratic innovations. Currently, she is on a research leave and leads a project entitled “Participation in Long-Term Decision-Making”, funded by the Strategic Research Council of the Academy of Finland.

Henrik Serup Christensen

Henrik Serup Christensen is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at Åbo Akademi University in Turku, Finland. His research interests include political behaviour broadly defined and the implications for democracy.

Mikko Leino

Mikko Leino works as a project researcher at the University of Turku. His research interests include deliberative democracy, democratic innovations and attitudes toward minorities. He has been involved in a number of projects experimenting with deliberative mini-publics.

Kim Strandberg

Kim Strandberg is Professor in political science, especially political communication at Åbo Akademi University. His research areas concern online campaign communication, civic participation and deliberative democracy. Strandberg has also conducted several experiments in both online and offline deliberation. He has published his research in journals such New Media & Society, Information Technology and Politics, and Party Politics.

Maria Bäck

Maria Bäck is PhD in political science. Currently she works as Senior Lecturer at the University of Helsinki. She is specialized in research on social and political trust, political attitudes and electoral behaviour. Her most recent projects revolve around research on citizen-elite opinion congruence and political participation in Finland and in Europe.

Maija Jäske

Maija Jäske is Postdoctoral Researcher in Political Science at Åbo Akademi University. She received her PhD at the University of Turku in 2019. Her research focuses on democratic innovations. Currently she is working on the questions of scaling up the effects of deliberative mini-publics and intergenerational attitudes. She has published in journals such as European Journal of Political Science and Swiss Political Science Review.

Notes

1 Appendix 1 contains a comparison of socio-demographic characteristics for Korsholm and all surveys. Despite the low response rate, the respondents resemble the general population when it comes to gender, language and place of living. Since the deadline for returning the survey related to the field experiment was rather short, the response rates were lower than the other surveys (77 respondents or 15.4% returned the survey in the control group, and 97 respondents (19.4% in the treatment group). This could cause systematic differences between the treatment and control groups, which could invalidate the experimental design and observed outcomes. Comparing mean scores between treatment and control group suggest that they are similar when it comes to age, language and place of living, but small differences existed when it comes to gender (treatment group mean = .54, SD = .05, control group mean = .41, SD = .06; t(171) = –1.68, p = .0475). We also found differences between the treatment and control group for level of education (treatment group mean = 2.02, SD = 0.14, control group mean = 1.64, SD = 0.15; t(160) = –1.86, p = 0.0324). To take these differences into account in the analyses, we in the reported results adjust for gender and education, although further analyses show similar substantial results when not doing so, meaning we are confident that these differences do not affect our conclusions. Since the differences compared to the general population are negligible, we do not weight the data when reporting the results.

2 A total of 130 responses were received in the control group, but 53 were returned after the release of the statement and since we cannot be certain that the respondents did not read the statement, these were excluded from the analyses. Additionally, we received 30 more responses in the treatment group after 1 March 2019, but since a considerable time elapsed since the release of the statement and there were rapid developments in the public opinions during this time, we excluded these to be certain that opinions and attitudes were not affected by factors other than the statement. Preliminary analyses suggest similar differences for other specifications of the groups.

3 We also measured trust in politicians opposing and supporting the merger, local media, experts and public servants in Korsholm. However, an exploratory factor analysis indicated that the trust items should not be combined to a single dimension and we therefore chose to focus on a single item with a clear-cut interpretation.

4 We obtain similar results when recoding the questions to focus only on factual knowledge and disregard the degree of certainty.

5 This is identical to an ANCOVA approach where group means are compared while controlling for covariates.

6 When instead examining only factual knowledge by coding the answer to each answer as leaning either true or false and combining them to an index ranging 0–10, the treatment group scores 1.1 higher on average. Analysis of the individual questions also shows that as might be expected, knowledge tend to improve on the items where the correct answer can be found in the statement.

References

- Ackerman, B., & Fishkin, J. S. (2002). Deliberation day. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 10, 129–152.

- Barber, B. 1984. Strong democracy: Participatory politics for a new age. University of California Press

- Boehmke, F. J. (2005). Sources of variation in the frequency of statewide initiatives: The role of interest group populations. Political Research Quarterly, 58, 565–575.

- Chambers, S. (2001). Constitutional referendums and democratic deliberation. In M. Mendelsohn & A. Parkin (Eds.), Referendum democracy. Citizens, elites and deliberation in referendum campaigns (pp. 231–255). New York: Palgrave.

- Chambers, S. (2009). Rhetoric and the public sphere: Has deliberative democracy Abandoned mass democracy? Political Theory, 37(3), 323–350. doi:10.1177/0090591709332336

- Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: HarperCollins.

- Ford, R., & Goodwin, M. (2017). Britain after Brexit: A nation divided. Journal of Democracy, 1, 17–30.

- Gastil, J. (2014). Giving voters viable alternatives to unreliable cognitive shortcuts. The Good Society, 23(2), 145–59.

- Gastil, J., Broghammer, M., Rountree, J., & Burkhalter, S. (2019). Assessment of three 2018 citizens’ initiative review pilot projects. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University. http://sites.psu.edu/citizensinitiativereview.

- Gastil, J., Johnson, G. F., Han, S., & Rountree, J. (2017). Assessment of the 2016 Oregon citizens’ initiative review on measure 97. State College, PA: Pennsylvania State University. http://sites.psu.edu/citizensinitiativereview.

- Gastil, J., & Knobloch, K. R. (2010). Evaluation report to the Oregon State legislature on the 2010 Oregon Citizens’ initiative review. Seattle, WA: University of Washington.

- Gastil, J., & Knobloch, K. R. (2020). Hope for democracy. How citizens can bring reason back into politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gastil, J., Knobloch, K. R., Reedy, J., Henkels, M., & Cramer, K. (2018). Assessing the electoral impact of the 2010 Oregon citizens’ initiative review. American Politics Research, 46(3), 534–563.

- Gastil, J., & Richards, R. (2013). Making direct democracy more deliberative through random assemblies. Politics & Society, 41, 253–281.

- Healthy Democracy (2020). Citizens’ initiative review. https://healthydemocracy.org/cir/, [accessed June 23, 2020]

- Hobolt, S., Leeper, T. J., & Tilley, J. (2020). Divided by the vote: Affective polarization in the wake of the Brexit referendum. British Journal of Political Science, doi:10.1017/S0007123420000125

- Ingham, S., & Levin, I. (2018). Can deliberative minipublics influence public opinion? Theory and experimental evidence. Political Research Quarterly, 71(3), 654–667.

- Jäske, M. (2017). ‘Soft’ forms of direct democracy: Explaining the occurrence of referendum motions and advisory referendums in Finnish local government. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(1), 50–76. doi:10.1111/spsr.12238

- Knobloch, K. R., Barthel, M., & Gastil, J. (2019). Emanating effects: The impact of the Oregon citizens’ initiative review on voters’ political efficacy, political studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321719852254

- Knobloch, K. R., Gastil, J., Reedy, J., & Walsh, K. C. (2013). Did they deliberate? Applying an evaluative model of democratic deliberation to the Oregon citizens’ initiative review. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 41(2), 105–125.

- Knobloch, K. R., Gastil, J., Richards R., & Feller, T. (2014). Empowering citizen deliberation in direct democratic elections: A field study of the 2012 Oregon citizens’ initiative review. https://journals.openedition.org/factsreports/3448

- LeDuc, L. (2002). Opinion change and voting behaviour in referendums. European Journal of Political Research, 41, 711–732.

- LeDuc, L. (2015). Referendums and deliberative democracy. Electoral Studies, 38, 139–148.

- Leeper, T. J., & Slothuus, R. (2014). Political parties, motivated reasoning, and public opinion formation. Advances in Political Psychology, 35, 129–156.

- Lijphart, A. (1984). Democracies: Patterns of majoritarian and consensus government in twenty-one countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Lupia, A., & McCubbins, M. (1998). The democratic dilemma: Can citizens learn what they need to know? New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Lutz, G. (2006). The interaction between direct and representative democracy in Switzerland. Representation, 42, 45–57.

- Már, K., & Gastil, J. (2020). Tracing the boundaries of motivated reasoning: How deliberative minipublics can improve voter knowledge. Political Psychology, 41, 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12591

- Morel, L. (2001). The rise of government-initiated referendums in consolidated democracies. In M. Mendelson & A. Parkin (Eds.), Referendum democracy: Citizens, elites and deliberation in referendum campaigns (pp. 47–64). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Pohjalainen (2019). Mustasaaren kansalaisraati grillasi poliitikkoja: Mihin perustuu väite, että Vaasasta ei saa palvelua ruotsin kielellä? Pohjalainen Newspaper (February 10). https://www.pohjalainen.fi/tilaajalle/maakunta/tilaajalle-7.3187110?aId=1.2873435 [accessed March 27, 2019]

- Qvortrup, M. (2017). The rise of referendums: Demystifying direct democracy. Journal of Democracy, 28, 141–152.

- Reilly, S., & Yonk, R. M. (2012). Direct democracy in the United States: Petitioners as a reflection of society. London and New York: Routledge.

- Setälä, M. (2006). On the problems of responsibility and accountability in referendums. European Journal of Political Research, 45, 701–723.

- Smith, M. A. (2002). Ballot initiatives and the democratic citizen. The Journal of Politics, 64(3), 892–903.

- Stojanovic, N. (2006). Direct democracy: A risk or an opportunity for multicultural societies? The experience of the four Swiss multilingual cantons. International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 8, 183–202.

- Strandberg, K., & Lindell, M. (2020). Citizens’ attitudes toward municipal mergers – individual-level explanations. Scandinavian Political Studies. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1467-9477.12170

- Suiter, J., Muradova, L., Gastil, J., & Farrell, D. (2020). Scaling up deliberation: Testing the potential of minipublics to enhance the deliberative capacity of citizens. Swiss Political Science Review. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/spsr.12405

- Suiter, J., & Reidy, T. (2013). It's the campaign learning stupid: An examination of a volatile Irish referendum. Parliamentary Affairs, 68, 182–202. doi:10.1093/pa/gst014

- Tierney, S. (2012). Constitutional referendums: The theory and practice of republican deliberation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Vasabladet. (2019). Medborgarrådet i Korsholm: Medlemmars bindningar väcker diskussion. Vasabladet Newspaper (February 12). https://www.vasabladet.fi/Artikel/Visa/267200 [accessed June 19, 2020]

- Warren, M. E., & Gastil, J. (2015). Can deliberative minipublics address the cognitive challenges of democratic citizenship? The Journal of Politics, 77, 562–574.

- Yle News (2019). Vårddirektör i Korsholm hotades på arbetsplatsen: “Fusionsfrågan har blivit oproportionerlig”. Finnish Broadcasting Company Yle (January 30). https://svenska.yle.fi/artikel/2019/01/30/varddirektor-i-korsholm-hotades-pa-arbetsplatsen-fusionsfragan-har-blivit [accessed June 19, 2020].

- Zimmerbauer, K., & Paasi, A. (2013). When Old and New Regionalism Collide: Deinstitutionalization of Regions and Resistance identity in municipality Amalgamations. Journal of Rural Studies, 30, 31–40.