?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This article examines the relationship between age and four types of political participation. Previous research has examined the age-participation nexus in the context of established democracies. In contrast, few studies have been devoted to assessing age differences in other contexts, particularly those of Africa, where the meaning of age and age groups could be different than in industrialised democracies. We argued in Africa that age's effect on political participation would vary depending on the country and across different forms of political participation. Analysing Afrobarometer survey data for 34 African countries, we find that the relationship between age and three forms of participation (voting, contacting and collective action) is curvilinear, with younger and older people less likely to participate. While for protest participation, the relationship between age and participation is linear, with protest decreasing with age. Next, we uncover that the countries’ policy formulation, implementation and electoral integrity affect the relationship between age and political participation. In contrast, breaking down the analysis into regional subsamples (West, Central, East, Southern, and North Africa), we observe no patterns of regional differences concerning political participation.

Introduction

Scholarly investigations into the relationship between age and political participation more than 50 years ago confirmed that age is an important predictor of participation (Campbell, Converse, Miller, & Stokes, Citation1960; Glenn & Grimes, Citation1968; Milbrath, Citation1965). Thanks to these studies, we know that the relationship between age and voting is curvilinear. Young people are less likely to vote, and voting increases from early adulthood to the senior years and then decreases (Franklin, Citation2004; Bhatti et al., Citation2012; Melo and Stockemer, Citation2014). Despite age being an important topic in political behaviour literature, studies analysing age differences in political participation are predominately Western-centric.Footnote1 It refers mainly to the experience of established democracies, which is often taken to be a universal trend for other geopolitical regions.

However, we argue that examining the relationship between age and political participation in other contexts, particularly those of Africa, could be beneficial from both a normative and theoretical point of view. First, the median age in Africa differs enormously from the rest of the world. For example, Africa's median age is 19.7 years, while Europe and North America are 42.5 and 38.8 years, respectively. However, we note there exist country-by-country variations across the continent. For instance, the median age in Niger, Mali, Chad, Somalia, Uganda, and Angola ranges between 15–16.7 years. In contrast, in Egypt, South Africa, Cape Verde, Algeria, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia and Seychelles, the median age ranges from 25 to 34 years.Footnote2

Second, the concept of age in Africa is not without controversy. For example, the United Nations consider young people to fall within the age brackets of 15–25 and those aged between 25–65 as the working age. Yet, the African Union strongly contests this age classification, considering young people between the age brackets of 15–35 (African youth charter, Citation2019). Third, young people in Africa are often celebrated as the driver of crucial political transformation that unfolded across the continent – notably during the period of decolonisation in 1960 and the period of pro-democracy movements that eventually led to democratic transition in the early 1990s (Branch and Mampilly, Citation2015, pp 67–69).Footnote3

So, with over 25 years since most African countries began having regular multiparty elections, it remains to be seen if the effect of age varies across countries and different forms of political participation. In this article, we compare the political participation of all age groups in institutionalised and non-institutionalised forms of participation. To our knowledge, only one study analysed the association between age and political participation (Resnick and Casale, Citation2014). Moreover, this study focused only on institutionalised participation (e.g. voting). On the other hand, some empirical studies included age as a mere control variable in their vote choice model (Bratton et al., Citation2005; Kuenzi & Lambright, Citation2011; Isaksson, Citation2014; Tambe, Citation2017; Citation2021). While these studies are relevant for our purpose of the age-participation nexus in Africa, there are still many caveats with these prior works.

First, prior studies focus extensively on voting and ignore how age might vary across different forms of political participation. Relatedly, they assume the relationship between age and turnout is linear. Although, for instance, in western democracies, we know that the relationship between age and voting is curvilinear, it is still essential to ask whether the same patterns are observed in Africa for institutionalised and non-institutionalised participation. And whether the decline arrives at about the same age as what holds for established democracies. Second, most studies treat Africa as a homogenous region without considering the continent's distinct political and cultural context (Englebert & Dunn, Citation2013; Reichenberg & Tambe, Citation2022).

This article argues that the relationship between age and political participation will vary across countries and different forms of political participation in Africa. In the recent decade, there has been an upsurge in non-institutionalised participation, mainly protest action across many African countries organised mainly by young people (Branch and Mampilly, Citation2015, pp 67 - 69). Furthermore, the African countries we analysed include a lot of variation in terms of political systems, ranging from democracies (Cape Verde, South Africa, Ghana, etc.) to fully authoritarian regimes (e.g. Sudan), ‘electoral authoritarian regimes’ and much variation in between flawed democracies and hybrid regimes. Thus, relying on the Afrobarometer data (round 7) conducted in 2019, consisting of 34 African countries and employing descriptive and multilevel modelling, our article makes a contribution to the literature in a context that only receives scant attention in offering a better understanding of how the effect of age on participation might be context-dependent and vary by form of political participation.

Age and Political Participation

Age and political participation are key themes in political science research, with the comparative literature providing varying expectations of this relationship. In this article, we adopt a classical approach that sees political participation as a multidimensional concept based on prior studies that examined modes of democratic participation (Verba et al., Citation1978). Thus, we include direct contact, collective/communal activityFootnote4, and demonstrations beyond voting. Furthermore, these forms of political participation are grouped into two dimensions – institutionalised and non-institutionalised for ease of theoretical discussion. We contend protest and collective/communal activityFootnote5 tap into contentious politics. As such, we consider both non-institutionalised participation. In contrast, voting and direct contact are more conventional or institutionalised forms of political participation (Verba and Nie, Citation1972; Verba et al., Citation1978).

On the other hand, we consider age to represent a life-cycle transition or development by which one moves through different periods. For example, young, middle-aged and old, from education to employment, dependence to autonomy and different periods of cognitive development, experiences and responsibilities (Roberts, Citation2009; Lloyd, Citation2005).Footnote6 These different life courses or experiences should influence how different age groups sees and thinks about politics.

In forming our theoretical expectation on how the effect of age might vary by form of political participation and across the country of residence, we build on literature that has theorised the role of individual traits and institutional factors in shaping political participation. Specifically, focusing on individual traits, we rely on the civic voluntarism model (Verba et al., Citation1995). The authors suggest three crucial factors, capacity, motivation, and network of recruitment, as essential for understanding the participatory process. At the same time, studies also argue the need to consider the institutional contexts. This perspective contends people's decisions to participate depend not only on individual factors but also on the context in which individuals find themselves (Franklin, Citation2004). Hence, institutional features such as economic development and democratic governance are relevant for understanding how countries’ contexts might influence political participation. However, in examining the age-participation nexus, we find the aspect of democratic governance (political system and government effectiveness etc.) more salient in the African context than economic development.Footnote7 However, rather than considering the institutional context in insolation, we argue they interact with different life-cycle to help determine age differences in political participation across countries. In the proceeding section, we develop two hypotheses on how the relationship between age and political participation in Africa will vary across different forms of political participation and across countries that tap into the individual and institutional perspectives.

HYPOTHESIS 1: We expect a significant positive association between institutionalised participation and age. In contrast, we expect a significant negative association between non-institutionalised participation and age.

However, non-institutionalised participation (e.g. protest and collective actions) are forms of activity used for voicing grievances and drawing attention to issues often ignored by the political elites (Melo and Stockemer, Citation2014) and are particularly common among young people. For instance, relying on the grievance theories, Mueller (Citation2018) highlights in Africa anger, economic deprivation, unemployment, and the desire to change the status quo as conducive to protest participation, particularly among young people.

Second, we contend that political knowledge and information should influence participation differences across different age groups. For example, Rubenson, Blais, Fournier, Gidengil, and Nevitte (Citation2004) argue that young adults’ reluctance to engage in electoral politics could be due to their lack of knowledge and interest in politics. Likewise, Torney-Purta’s (Citation2002); Pacheco's (Citation2008) studies on socialisation theories suggest that socialisation and political discussion within the family help harness political engagement among young adults. Yet, as Blanc et al. (Citation2013) revealed within Europe, which we expect to be true in Africa, the family as the most crucial socialisation mechanism plays less of a significant role today than a generation ago, thus breaking the traditional channels through which young people will tend to access political knowledge/information necessary for participation.

Although the lack of political knowledge, information and interest tends to lower the participation of young people in more formal modes of engagement compared to older people, in the recent decade, there has been an increase in alternative sources of information in the form of media access. However, the relationship between media exposure and participatory pattern in Africa is mixed. Kuenzi and Lambright (Citation2011) show individuals who listen to the radio are more likely to vote, while Mattes and Mughogho (Citation2009) find a positive association between media exposure and contact and protest in Africa. However, the authors show that media exposure is associated with decreased formal participation, notably voting. Relatedly, other studies have attempted to provide a causal link between media exposure and political participation in Africa (for an overview, see, Conroy-Krutz, Citation2018). Moehler and Conroy-Krutz (Citation2016) contend media exposure tends to increase cognitive political engagement, while Mattes and Mughogho (Citation2009) posit media exposure does affect individuals’ sense of efficacy and political knowledge, which therefore increase participation (or the lack of it).

At the same time, these studies describe the link between political knowledge, media exposure and participation. Still, for our purposes, the question is how citizens’ access to alternative forms of information, particularly the internet, phones, WhatsApp, and Facebook, impacts age differences in other types of participation. In Africa, young people tend to have greater exposure than older people to social media, compensating for the loss of information via traditional sources (socialisation via family and friends). However, we ask about the implications of these differences for their participation are? Is the information available through alternative sources of similar quality as what can be found in traditional media, and is it as effective for political participation? Bleck and van De Walle (Citation2018) reveal that social media have created an opportunity for young people to share their grievances by voicing them online and on social networks. And, of course, the implication is that it has acted as a cognitive catalyst that pushes them to engage more in protest and collective/community actions.

HYPOTHESIS 2: We expect the relationship between age and political participation to be moderated by the country's political characteristics – notably democratic governance.

First, we begin with political freedom. Given that there are so many variations in the regime type operating across the continent, ranging from democracies to non-democracies, age differences in participation might vary according to the political system. Regarding voting, Kuenzi and Lambright (Citation2011); Resnick and Casale (Citation2011) show the context of political freedom across African countries does not influence overall participation. Still, we deem older people, compared to younger people, would be more drawn to participate in institutionalised activities in countries with better democratic quality and freedom since they already possess the resource and skills that permit them to participate at a higher rate. In contrast, younger people should be more likely to engage in contentious politics in countries where democratic quality is undermined and restricted. Our argument seem justified given that participation in a context with limited freedom comes at a high cost or risk, which young people could bear, given they tend to be more dissatisfied with government performance and resentful about the state of affairs. Antecedent evidence shows young people in Africa were more involved in protest and collective action during the pro-democracy movement against the one-party rule (Bratton et al., Citation1994; Brown, Citation2004).

Second, we approach government effectiveness, which refers to the government's capacity to develop and implement policies effectively (Worldwide governance indicators, Citation2020). Data from the World Bank suggest that government effectiveness tends to be low across most sub-Saharan African countries compared to OECD countries. However, this low level of government effectiveness should not mask the slight variations among sub-Saharan African countries. For instance, government effectiveness is slightly higher in a few countries such as Namibia, Mauritius, and South Africa (Worldwide governance indicators, Citation2020). Although government effectiveness is relatively low across the African continent amidst a few variations yet, for our purposes, we are more interested in how government effectiveness would affect age differences in political participation. Thus, the central idea here is that if the government can get things done, this will create a sense among individuals that the states will be willing to consider their demands, thus boosting the possibility that actions will lead to substantive change. Whiteley's (Citation2009) analyses of government effectiveness and political participation confirm a high level of political engagement tends to go with a high level of government effectiveness. In Africa, Azarya and Chazan (Citation1987) show the state tends to consider a means of fulfilling citizens’ social and economic aspirations. Thus, poor state performance tends to be associated with disengagement from the state (Englebert Citation2002). Still, for our concern, we ask how government effectiveness impacts different age groups. Unfortunately, scholarly research is completely void on the effect of government effectiveness on the participatory pattern of the different age cohorts. However, the general expectation is that individuals with a higher perception of government effectiveness are more likely to participate because they have the confidence doing so will lead to the desired outcome (van Zomeren et al., Citation2008). Given the lack of scholarship on the effect of government effectiveness on the participatory pattern of different age groups, we still expect countries with higher government effectiveness to boost participation from all ages. Still, we expect the participation of younger people more than older people in non-institutional activity to be more substantial in countries with poor government effectiveness.

Third, regarding corruption, Lodge (Citation2019) and as exemplified by Transparency International Corruption Index (2020), corruption is more prevalent in Africa than in any other global region. Yet, it tends to vary a great deal between countries. For instance, while Mauritius, Botswana, and Cape Verde are considered the least corrupt countries in Africa, others, such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, have the highest rates of corruption (Corruption perception index, Citation2020). Moreover, evidence reveals corruption is a significant barrier to economic growth, good governance, and democratic freedoms across the continent (Corruption perception index, Citation2020). Warren (Citation2004) posits that corruption can corrode or threaten political institutions and the very foundation of democracy itself.

So, the question that can be posed is how does corruption shape age differences in political participation? The Global Corruption Barometer index (Citation2020) suggests that corruption disproportionately affects Africa's most vulnerable (poor or less affluent). Most importantly, young Africans tend to pay more bribes than those over 55. However, since corruption tends to vary across African countries, we contend it might affect the participation pattern of different age groups almost the same way. This implies that corruption could dampen a voter/activist spirit in a high corrupt setting and reinforce a sense that participation will not be sufficient to bring change. Specifically, in countries where people feel corruption is pervasive, the participation rate of all age groups will be lower in such a context. While in settings or countries where individuals perceive corruption to be relatively low, in such countries, an increase in the perception of corruption would foster participation from at least younger age groups to kick the rascal out (Johnson & Kaye, Citation2003; Dahlberg & Solevid, Citation2016).

Fourth, we examine the impact of electoral integrity in explaining age differences in political engagement in Africa. Even though elections are now well-thought-out as the primary source for choosing national leaders/local representatives across most African countries, the integrity of these elections tends to vary, ranging from free and fair elections with genuine contestation to those considered fraudulent, manipulated, and marred by irregularities. Survey evidence from the Afrobarometer suggests that elections in Africa tend to suffer from two major irregularities: whether votes are counted fairly and issues about the opposition being prevented from running. Regarding whether elections are free and fair, a list of suspicious results includes those of the Cameroonian election in 1992 and 2018, Zimbabwean elections of 2008, Togolese elections of 2005, Kenyan elections of 2007, and Nigerian elections of 2001, where it was thought the incumbents received fewer votes than their challengers. However, Arriola (Citation2013) shows that African incumbents’ average margin of victory was 40 per cent higher than that in other regions. Resnick and Casale (Citation2011) find the perception of electoral integrity, i.e. whether an election was free and fair, tends to increase the likelihood of all age groups to vote, which we expect to come true with other forms of participation.

Data and Methods

Data

To examine whether the relationship between age and political participation in Africa will vary across countries and different forms of political participation, we rely on the Afrobarometer survey data. Specifically, we rely on Afrobarometer round 7 data that covers a total of 34 African countries (i.e. which are considered the major multiparty regimes in the region) with a representative sample size of 1200 in each country, except for Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, where the sample is twice the size (i.e. 2400).

Theorising Political Participation in Africa – Dependent Variables

In this study, as mentioned above, we see political participation as a multidimensional concept and rely on survey data to help theorise different political activities in Africa. Particularly, the Afrobarometer (AB) survey data provides a more context-specific and meaningful conceptualisation of political activities in the African context, with citizens being asked a battery of questions, which forms the basis for our analyses of participation patterns. Round seven data asked respondents in national representative samples to describe their past participation in various political activities. According to the data, many citizens participate in at least one form of political participation. Thus, the respondents participate in 10 forms of political activities. Based on the previous suggestions of the political participation research scholars, we combine/reduce these 10 distinct types of political activities to four dimensions of political participation across the continent, which are grouped into.

voting (in Afrobarometer (Citation2019): ‘voted in the most recent national election’);

communal or collective action (in Afrobarometer (Citation2019): ‘joined others to raise an issue’, ‘attended a community meeting’, and ‘joined others to request government action’);

contacting (in Afrobarometer (Citation2019): contacted a local government councillor/member of parliament/official of a government agency/political party official/traditional ruler or chief about some important problem or to give them your views) and

protest participation (in Afrobarometer (Citation2019): ‘participated in a demonstration or protest march’).

Since all of the mentioned variables have a categorical and, in almost all cases (except for the voting that is measured on a ‘nominal’ scale), ordinal scale, we used multiple correspondence analysis for categorical data (Husson, Lê, & Pagès, Citation2017) to reduce the number of dimensions to the needed four. Therefore, the four main dependent variables are measured in the following ways. First, voting and protesting are collapsed into dichotomous (i.e. participated - did not participate) variables. Second, because some respondents were prevented from voting, an additional control variable regarding participation in voting was created. This variable was coded as a dichotomous variable as well. Finally, the remaining two dependent variables: contacting and collective/communal actions - were measured as continuous interval variables after performing multiple correspondence analyses on ordinal variables. Lower values were associated with low participation and higher values with high/frequent participation (see Table 2 of the Supplementary information to know more about the levels of measurement).

Independent and Control Variables

The primary independent variable of interest in this study is age. Interpreting the results, we regard age as values falling into two categories: young people (18-35 years) and non-youth. When conducting the analysis, we use age as a continuous variable and control for both linear and curvilinear effects of age (Kern et al., Citation2015) on participation in different forms of political activities.

We now turn to explain how other independent variables that capture the theories of political participation are measured. First, beginning with the resource theories, we examine respondents’ level of education and material wealth (i.e. a proxy for income). Education was, therefore, measured on a 0–9 index ranging from no formal schooling to postgraduate education. Material wealth is measured by the Afrobarometer lived poverty index, which averages an index of the 6 poverty items. Once again, multiple correspondence analysis was applied to the 6 variables operationalising access to the poverty items, which reduced the number of dimensions to the needed one.

Second, we include a news access variable to appraise the political knowledge/information approach. The question asks, how often do you watch/listen/read radio/TV/newspaper/Internet/social media news? After conducting multiple correspondence analyses, we received one variable, i.e. ‘access to news’. Next, we include a variable discussing politics and associational membership (i.e. belonging to a religious group, belonging to a community group), which taps into the socialisation within family, friends, and other informal networks. Finally, as Verba, Schlozman, & Brady (Citation1995) suggested, we also control party identification.

Third, we control for other individual-level variables, notably residency area, ethnic identity, being employed and being the head of the household. Those variables are shown to significantly impact patterns of political participation in general (as suggested by Verba, Schlozman, & Brady, Citation1995) and, in particular, in Africa (see Tambe, Citation2017, Citation2021; Resnick & Casale, Citation2014; Kuenzi & Lambright, Citation2011).

Four, moving to the institutional characteristics, we measure democratic governance by including four institutional-level variables, i.e. the Freedom House index (Freedom in the world, Citation2020), World Bank governance index (Citation2020), Transparency International corruption perception index (CPI)(2020) and the Perception of Electoral Integrity (PEI) index (Citation2019). Four variables are highly correlated with one another (see the Supplementary R script). Thus, after applying confirmatory factor analysis (Revelle, Citation2020), we reduced them to one variable titled ‘democratic governance’ (DG).

Method

We analyse the data applying multilevel multiple regression analysis with interaction effects.Footnote10 Due to the fact that after conducting multiple correspondence analysis, two out of four dependent variables are measured on an interval scale, in the case of participation in contacting and in collective actions, multilevel linear regression analysis was applied. While, in the case of participation in voting and protesting, logistic regression models were fitted.

To access the country differences in relation to the effect of age on political participation, we compared the fits of two model designs: the model with a random intercept design (Model 1) and the model with a random slope design (Model 2). The second model allows the age to affect participation differently depending on the country of residence. In all of the cases, the second model had a better fit. The finding is in line with the previous suggestions of Jan Paul Heisig and Merlin Schaeffer. They proposed that random slopes for the lower-level variables (in our case, age and age2) involved in cross-level interactions should always be included in the multilevel multiple regression models (Heisig & Schaeffer, Citation2019). Moreover, the model design corresponds with our expectations about country differences regarding the relationship between age – political participation. Thus, in the Results section, we will only report the estimates received by fitting this model. The model was defined as follows.

Results

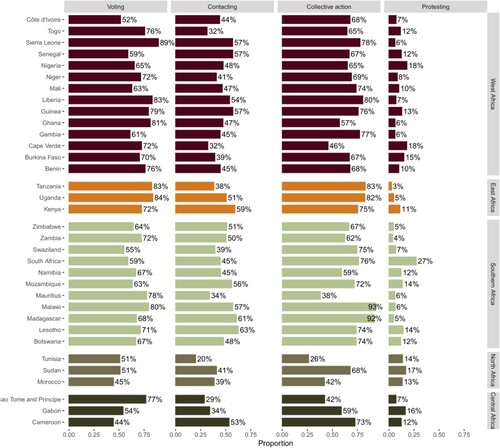

In regard to political participation, the majority of the examined population, i.e. 68% of people (see ), voted in the latest national election. This is considering that at least 10% of respondents (4450 out of 45534 people) stated they were prevented from voting. Moreover, 8% of the respondents disclosed that they were not registered to vote.

Table 1. Number of people participating in different forms of political participation. Source: Afrobarometer (Citation2019).

shows that the second most popular type of political participation in Africa is participation in collective action. More than half of the respondents (i.e. 68%) stated that they ‘attended a community meeting’, joined the others to ‘raise an issue’ or ‘to request government action’. Contacting is another institutionalised political activity in which almost half of the respondents (i.e. 46%) participated. In the meanwhile, in protesting, only 11% of the respondents participated during the past year.

shows the country's differences in regard to the number of respondents in different types of political activities. supports the assumption that country units, rather than region units, must be considered when analysing the predictors of political participation. Thus, no patterns of regional differences in regard to political participation can be seen in .

Figure 1. Participation in different types of political activities by country. Source: Afrobarometer (Citation2019). Notes: N = 44,885-45,762 individuals in 34 countries. Entities are the proportions of respondents who answered the survey’s question in regard to the specific type of political participation.

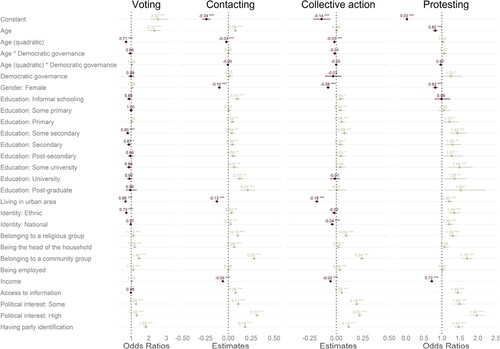

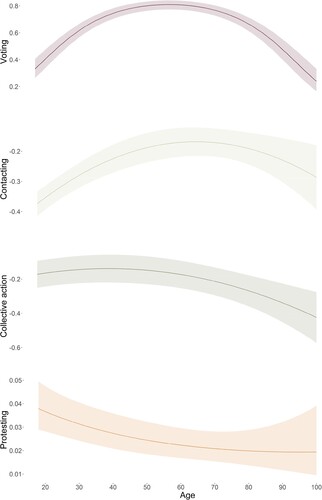

Estimating the random slope model in regard to participation in different forms of political activities, we can see that the effect between age and participation is often curvilinear (see and ). Still, the curve is more visible in the cases of institutionalised participation, i.e. voting and contacting. shows that older people (i.e. over 35 y.o.) are more likely to participate in institutionalised activities. Yet, the elderly (over 80 y.o.) do not participate as much. Because the interquartile range of age in African countries lays roughly between the 25th percentile of the early 20s to the 75th percentile of the late 50s (see of the Supplementary material), we can conclude that older people are more likely to participate in institutionalised activities.

Figure 2. Model 2 estimates and odds ratios for different forms of political participation. Notes: N = 30,176-30,599 individuals in 25 countries. Mixed-effect logistic and linear regressions were applied to analyse the data. Entities are the estimates and odds ratios, and corresponding confidence intervals (CI). Sign.: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. Age is an individual-level variable. Prior to the analysis, the age variable was centred and scaled to 10:1.

Figure 3. The relationship between age and participation in different forms of political activities. Entities are the regression plots showing the relationship between age (X-axis shows the values of age) and participation in voting, contacting, collective action and protesting (Y-axis shows the predicted values of participation).

Comparing all of the curves showing the association between age and participation (), we can see that the voting curve, – if compared to others – is much flatter on top. That signifies that while only a few age groups participate in contacting, collective actions and protesting, many generations participate in voting. Examining the association between age and non-institutionalised participation, we can see that the relationship is linear in the case of protesting and next to linear in the case of ‘Collective action’ participation (see and ). Still, the groups that are most likely to participate in collective actions are people in their mid-30s-mid-40s, which is outside the youth brackets. Thus, H1 is only partly supported by the data.

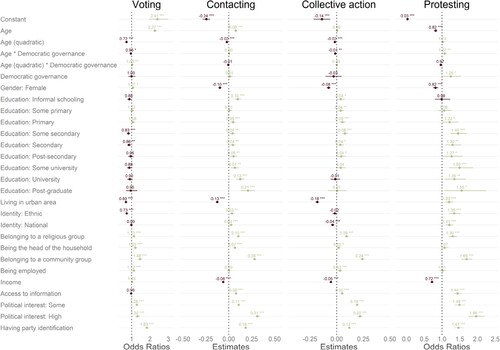

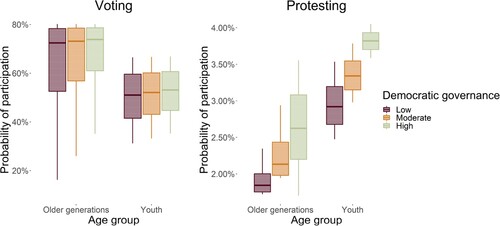

When measuring the effects of the country-level variable democratic governance on the relationship between age and different forms of political participation, we found the moderating effect of DG to be insignificant. Thus, H2 is not supported by the data. This means that the relationship between age and participation varies between countries and is affected by more than one country's characteristics. We can compare this result to the significance of the estimates when fitting Model 1. shows DG to have a significant moderating effect on the relationship between age and participation in voting, collective actions and protesting. Yet, the effect is the most pronounced in the case of voting and protesting. Despite our expectations, participation in voting – a classical example of institutionalised activity – and protesting (i.e. a classic example of non-institutionalised activity) increases when DG is high. Thus, in particular, youth protests more in countries with higher DG (see ).

Figure 4. Model 1 estimates and odds ratios for different forms of political participation. Entities are the estimates and odds ratios, and corresponding confidence intervals (CI). Sign.: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Figure 5. Effect of DG on the relationship between age and voting and protesting. The boxes represent the interquartile range of the participation probability values. The whiskers cover the upper and lower quartiles. The vertical line inside each box is the median of the values.

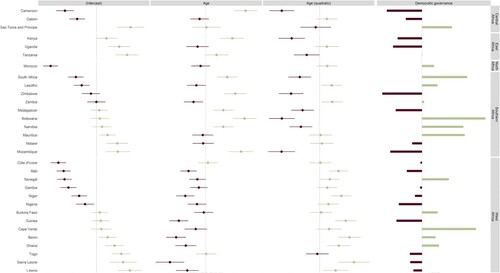

We see the most country variation in respect to the relationship between age and voting. shows no regional trends: e.g. in the East African region, the relationship between age and voting, while being U-shaped in Uganda, is inverted-U-shaped in Kenya and Tanzania. confirms that there is some correspondence of the county-level variation of the estimates with the values of DG. Still, the effect of the country-level variable alone cannot explain this variation.

Figure 6. County-level variation of the estimates and their corresponding confidence intervals in relation to participation in voting.

In regard to the association with the control variables, in the African context, income once again showed to be a significant predictor of political participation in all forms of political activities, except for voting (see ). Thus, lower-income people are more likely to participate in contacting, protesting and collective actions. The level of education, political interest, political knowledge, and party identification showed a significant positive association with almost all forms of political participation except voting, which is neither increasing nor decreasing with the growth in political knowledge. Concerning the influence of gender, it is evident that women are less likely to participate in contacting, protesting, and collective actions. Meanwhile, those living in urban areas participate in protesting more than those in rural areas. In contrast, the last ones are more likely to participate in voting, contacting, and collective actions. National identity is another significant predictor of political participation. Thus, those characterising their identity as ethnic are less likely to participate in voting, while those with national identity are less involved in collective actions. Being employed and the head of the household increases participation in all forms of activities except protesting. Meanwhile, membership in a community or religious group is positively associated with all forms of participation.

Discussion

This paper's core objective was to demonstrate two related ideas: First, to show that the relationship between age and political participation varies across countries. Second, to show that the effect of age varies across different forms of political participation. Having concluded the analysis, our results show different age effects for different forms of participation. First, we confirm the hypothesis that age is associated with increased participation in various political activities, which varies by age. For instance, regarding participation in institutionalised political activities, i.e. voting, contacting, and collective actions, we find the curvilinear effect of age is significant and negative (see ). These results suggest that younger and older people, in comparison to middle-aged residents, are less likely to participate in the specified forms of political activities. In particular, and relating to voting, we find that those between 45 and 68 are the most active participants across the African continent.

While pertaining to contacting those between 18–35 years participate less, while people of 65–70 age group participate the most. Regarding collective action, the groups most likely to participate are those in their mid-30s-mid-40s (i.e. older people, according to our discussion of age cohorts in Africa). Alternatively, younger cohorts are more likely to participate in elite challenging activities (protest). Overall, the bigger picture concerning age and political participation in Africa mirrors those of established democracies (i.e. age is associated with increased participation in various political activities, and this varies by age).

Second, we contend there are important regional differences between North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa and even between Southern, Central and East Africa. To evaluate the extent of these regional differences, we reject a sense of geography and location specificity by comparing the different sub-regions as units of analysis. Evidence shows no patterns of regional differences in political participation when exploring the heterogeneity in the age-political participation nexus across different African regions.

Third, we examine how the effect of age on participation might be context-dependent and vary by a country's political freedom, corruption level, government effectiveness, and electoral integrity. Specifically, we examine how these factors may moderate the relationship between age and different types of participation in Africa. For example, we found that the quality of policy formulation and implementation significantly affects the relationship between age and contacting and protesting. At the same time, the perception of electoral integrity affects the associations of age voting and age-protesting. In particular, with the decrease in the quality of policy formulation and implementation, older people (i.e. people of 35+) are much more likely to participate in contact than if the quality of policy formulation and implementation was high. In addition, we can see that participation in protesting is linear when political freedom levels are moderate (with youth more likely to engage). Relatedly, for electoral integrity, we show that people residing in countries with low levels of electoral integrity participate in protesting less. Also, our data suggest participation in voting slightly increases with the growth of electoral integrity in the country.

These findings also leave some interesting theoretical and practical implications that deserve attention for future scholarships. For example, young people were less likely to engage in voting, collective actions, and contact. Since young people are generally regarded as future democrats, this is quite a worrying finding for the prospect of democratic consolidation and political stability across the African continent, especially as the current youth bulge and the possibilities of this increasing in the next 20–30 years. Moreover, their lack of participation might undermine their representation in politics and national assemblies and lessens their ability to influence the policies that directly affect their lives (Stockemer and Sundström Citation2018). Consequently, much of the reluctance among youth to engage in more formal modes of participation has to do with their limited access to resources. It might be that one of the apparent remedies would be for policymakers/politicians to aim at reducing inequalities, particularly those that tend to deprive or hinder young people from socioeconomic institutions. Finally, this study highlights the need for panel data that would permit future studies to consider changes over time in the effect of age on political participation in Africa. Relatedly, another line of inquiry would be to explore how political participation among young people might have changed over time in the face of higher youth unemployment.

Supplementary_Material.doc

Download MS Word (361 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elvis Bisong Tambe

Elvis Bisong Tambe is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at Linnaeus University, Sweden. His research interests lie in the field of political behaviour, political participation, public opinion, voting and electoral processes, with a focus on new and emerging democracies. He is the author of Electoral Participation in Newly Consolidated Democracies: Turnout in Africa, Latin America, East Asia and Post-Communist Europe (Routledge, 2021).

Elizaveta Kopacheva

Elizaveta Kopacheva is a doctoral student in Political Science at Linnaeus University, Sweden. Her interest focuses on political behaviour, notably explaining factors that influence people to participate in online activism and other online political activities, e.g., petition signing or contacting.

Notes

1 This is obvious as Western democracies had by far the most extensive history with democracy and competitive elections.

2 https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/median-age (Accessed, 2022-05-12).

3 For instance, university students initiated a nationwide protest in Malawi that ended one-party rule in 1992. In Zambia, student protests ultimately culminated with Kenneth Kaunda's holding multiparty elections in 1991. In Ghana, young people were instrumental in fighting for independence by mobilising support around Kwame Nkrumah's Convention People's Party (CPP). Relatedly, secondary school students were at the forefront of the Soweto uprising against the apartheid policies in South Africa.

4 In this article, we use the terms collective and communal activity interchangeable as it involves citizens working with a group in a community for a particular course or purpose.

5 Communal activities are those activities that allow citizens to work together on a common interest. In most instances, they are used as tools for voicing grievances and drawing attention to issues often ignored by the political elites

6 We thank a reviewer for helping us make more clear what age means.

7 For one, we contend that the country's economic development is often contingent on democratic governance. For instance, corruption which is very widespread in Africa, can be a significant barrier to economic growth and development. But even so, there seems to be little or no variation in key economic indicators such as income inequality and per capita GDP across the African countries that form the focus of this study, at least for the period we cover. In addition, Bratton (Citation1999) argues that institutional context seems more important than economic or cultural aspects.

8 Dawson (Citation2014) described this waithood period as the widening gap between aspirations and lived realities, which is emphasised by the sense that some people get richer at the expense of those at the bottom of society. The implication is that waiting represents the lived reality of being unable to attain markers of adulthood and respectability at the individual level, therefore prolonging 'youthhood'.

9 In our results section, we report our findings based on the quality of policy formulation and implementation.

10 All of the individual-level variables are weighted.

References

- Abbink, J. (2005). Being young in Africa: The politics of despair and renewal. In J. Abbink, & I. van Kessel (Eds.), Vanguard or vandals: Youth, politics and conflict in Africa (pp. 1–33). Brill.

- African youth charter. (2019). African Union. https://au.int/en/treaties/african-youth-charter.

- Afrobarometer: Merged data. (2019). Afrobarometer. https://afrobarometer.org/data/merged-data.

- Arriola, L. (2013). Protesting and policing in a multiethnic authoritarian state: Evidence from Ethiopia. Comparative Politics, 45(2), 147–168. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041513804634271

- Azarya, V., & Chazan, N. (1987). Disengagement from the state in Africa: Reflections on the experience of Ghana and Guinea. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 29(1), 106–131. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500014377

- Bhatti, Y., Hansen, K. M., & Wass, H. (2012). The relationship between age and turnout: A roller-coaster ride. Electoral Studies, 31(3), 588–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.05.007

- Blanc, A., Cavazza, N., Corbetta, P., Fournier, B., Galais, C., Garcìa-Albacete, G., Haug, L., Paul, R., Quintelier, E., Schwarzer, S., & Tuorto, D. (2013). Growing into politics: Contexts and timing of political socialisation. Ecpr Press.

- Bleck, J., & van de Walle, N. (2018). Electoral politics in Africa since 1990: Continuity in change. Cambridge University Press.

- Branch, A., & Mampilly, M. (2015). Africa uprising: Popular protest and political change. Zed Books.

- Bratton, M. (1994). Civil society and political transition in Africa. Institute for Development Research (IDR).

- Bratton, M. (1999). Political participation in a new democracy. Comparative Political Studies, 32(5), 549–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414099032005002

- Bratton, M., Mattes, R., & Gyimah-Boadi, E. (2005). Public opinion, democracy and market recovery in Africa. Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, S. (2004). “Born-again politicians hijacked our revolution!”: Reassessing Malawi’s transition to democracy. Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne des études Africaines, 38, 705–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/00083968.2004.10751305

- Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Conroy-Krutz, J. (2018). Media exposure and political participation in a transitional African context. World Development, 110, 224–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.002

- Corruption perception index. (2020). Transparency International. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020/index/nzl.

- Dahlberg, S., & Solevid, M. (2016). Does corruption suppress voter turnout? Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 26(9), 489–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2016.1223677

- Dalton, R. J. (2017). The participation gap: Social status and political inequality. Oxford University Press.

- Dawson, H. (2014). Youth politics: Waiting and envy in a South African informal settlement. Journal of Southern African Studies, 40(4), 861–882. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2014.932981.

- Englebert, P. (2002). State legitimacy and development in Africa. Lynne Rienner.

- Englebert, P., & Dunn, K. C. (2013). Inside African politics. Lynne Rienner Publisher.

- Franklin, M. (2004). Voter turnout and the dynamics of electoral competition in established democracies. Cambridge University Press.

- Freedom in the world. (2020). Freedom House. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world.

- Glenn, N. D., & Grimes, M. (1968). Aging, voting, and political interest. American Sociological Review, 33(4), 563–575. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092441

- Global corruption barometer. (2020). Transparency International. https://www.transparency.org/en/gcb.

- Heisig, J. P., & Schaeffer, M. (2019). Why you should always include a random slope for the lower-level variable involved in a cross-level interaction. European Sociological Review, 35(2), 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcy053

- Honwana, A. (2012). The time of youth: Work, social change and politics in Africa. Lynne Rienner Publisher.

- Hunter, M. (2007). The changing political economy of sex in South Africa: The significance of unemployment and inequalities to the scale of the AIDS pandemic. Social Science & Medicine, 64(3), 689–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.015

- Husson, F., Lê, S., & Pagès, J. (2017). Exploratory multivariate analysis by example using R. CRC Press.

- Isaksson, A.-S. (2014). Political participation in Africa: The role of individual resources. Electoral Studies, 34(2014), 244–260.

- Jeffrey, C. (2010). Timepass: Youth, class, and the politics of waiting in India. Stanford University Press. http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id = 17650.

- Johnson, T. J., & Kaye, B. (2003). A boost or bust for democracy? Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 8(3), 9–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1081180X03008003002

- Kern, A., Marien, S., & Hooghe, M. (2015). Economic crisis and levels of political participation in Europe (2002–2010): The role of resources and grievances. West European Politics, 38(3), 465–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.993152

- Kuenzi, M., & Lambright, G. M. (2011). Who votes in Africa? An examination of electoral participation in 10 African countries. Party Politics, 17(6), 767–799. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810376779

- Lloyd, C. B. (2005). Growing up global: The changing transitions to adulthood in developing countries. The National Academies Press.

- Lodge, T. (2019). Corruption in African politics. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics.

- Mattes, R., & Mughogho, D. (2009). The limited impacts of formal education on democratic citizenship in Africa. Afrobarometer Working Paper, 109. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan

- Melo, D., & Stockemer, D. (2014). Age and political participation in Germany, France and the UK: A comparative analysis. Comparative European Politics, 12(1), 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.31

- Milbrath, L. W. (1965). Political participation: How and why do people get involved in politics? Rand McNally & Company.

- Moehler, C.-K. (2016). Partisan media and engagement: A field experiment in a newly liberalized system. Political Communication, 33(3), 414–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1069768

- Mueller, L. (2018). Political protest in contemporary Africa. Cambridge University Press.

- Pacheco, J. S. (2008). Political socialization in context: The effect of political competition on youth voter turnout. Political Behavior, 30(4), 415–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-008-9057-x

- Perceptions of electoral integrity dataverse. (2019). Harvard Dataverse. https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/PEI.

- Reichenberg, O., & Tambe, E. B. (2022). The political sociology of voting participation in Southern Africa: A multilevel study of regional and social class predictors in 11 countries. International Journal of Sociology 52(2), 156–177.

- Resnick, D., & Casale, D. (2011). The political participation of Africa’s youth: Turnout, partisanship, and protest. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/54172.

- Resnick, D., & Casale, D. (2014). Young populations in young democracies: Generational voting behaviour in sub-saharan Africa. Democratization, 21(6), 1172–1194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2013.793673

- Revelle, W. (2020). Psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research. Evanston. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package = psych.

- Roberts, K. (2009). Youth in transition: Eastern Europe and the west. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rubenson, D., Blais, A., Fournier, P., Gidengil, E., & Nevitte, N. (2004). Accounting for the age gap in turnout. Acta Politica, 39(4), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500079

- Stockemer, D., & Sundström, A. (2018). Age representation in parliaments: Can institutions pave the way for the young? European Political Science Review, 10(3), 467–490. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773918000048

- Tambe, E. B. (2017). Electoral participation in African democracies: The impact of individual and contextual factors. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 55(2): 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/14662043.2017.1274868.

- Tambe, E. B. (2021). Electoral participation in newly consolidated democracies: Turnout in Africa, Latin America, East Asia and Post-Communist Europe . Routledge.

- Torney-Purta, J. (2002). The school’s role in developing civic engagement: A study of adolescents in twenty-eight countries. Applied Developmental Science, 6(4), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0604_7

- Van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychological Bulletin, 134(8), 504–35. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.4.504

- Verba, S., & Nie, N. (1972). Participation in America: Political democracy and social equality. Harper and Row.

- Verba, S., Nie, N., & Kim, J. O. 1978. Participation and political equality: A seven nation comparison. Cambridge University Press.

- Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press.

- Warren, M. (2004). What does corruption mean in a democracy? American Journal of Political Science, 48(3), 328–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00073.x

- Whiteley, P. (2009). Government effectiveness and political participation in britain. Representation, 45(3), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344890903129459

- Worldwide governance indicators. (2020). The World Bank. Retrieved from https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worldwide-governance-indicators.