ABSTRACT

Transparency is core to the principles of electoral oversight. The disclosure of information is designed to allow voters, the media, academics, and civil society to hold political actors to account. However, in the context of evolving campaign practice occasioned by the rise of digital technologies, the effectiveness of transparency mechanisms needs to be consistently scrutinized (Electoral Commission. (2018). Digital campaigning: increasing transparency for voters. Electoral Commission.). In this paper we examine a lauded system of electoral transparency – the UK's electoral finance regime (Power, S. (2020). Party funding and corruption. Palgrave MacMillan) – and evaluate its effectiveness. Analysing a unique dataset of 22,720 separate items of expenditure and 5,770 invoices recording campaign spending at the 2019 UK general election, we review the sufficiency of the process and content of existing transparency disclosures. Our findings show significant deficits in the system of electoral transparency. We find that UK parties are not reporting data consistently, meaning that invoices are regularly uninformative, and that existing reporting categories are unable to capture the full spectrum of electoral activity. These findings are significant for understanding the requirements of an effective disclosure regime, but also for questioning the utility of the disclosures available to voters.

Introduction

The practice of election campaigning is in a constant state of flux due to many contextual issues including the availability of technologies. As detailed by a rich academic literature, political parties and other campaigning organisations have historically adapted to the emergence of new technologies (Karlsen, Citation2013; Magin et al., Citation2017) and campaigning ideas (Dommett & Temple, Citation2018; Gibson, Citation2013). These evolutions can serve as an important means of offering democratic linkage between citizens and the state (Lawson, Citation1980), and yet they can also disrupt prevailing democratic norms. Whilst often loosely specified, it is common to encounter the idea that election campaigns should be open and transparent, that citizens should be informed and able to understand attempts to influence their vote, and that elections should be conducted in a free and fair manner (Dahl, Citation1989; Gauja, 2020; Johnston, Citation1997). The advent of digital technology, and in particular the rise of campaigning on social media, has been seen to pose a threat to these ideals (Forestal, Citation2022; Norris, Citation2012; Tucker et al., Citation2017), making it more challenging to understand what campaigning activity is occurring, and whether these practices are democratically acceptable. Whilst many scholars have cast empirical light on the conduct of modern election campaigning (Gibson, Citation2020; Kefford, Citation2021; Nielsen, Citation2012), within this paper we instead consider the sufficiency of existing information disclosure systems, asking what information they provide for voters.

To interrogate this question, we scrutinize long-established state-systems of electoral transparency. Forms of electoral finance transparency are implemented in jurisdictions around the world, and capture information about the conduct of campaigns. The broad aim is to enable independent scrutiny and oversight, but it is unclear whether existing transparency disclosures are all that informative. In particular, there are unanswered questions about the degree to which the process (i.e. how information is disclosed) and the content (i.e. what information is disclosed) of disclosure aids the understanding of modern elections. Accordingly, we pose the research question: ‘How informative is the UK's system of electoral finance disclosure as it relates to party spending at general elections?’ Considering this question, we discuss the consequences of current disclosure practices for ordinary citizens, and ask whether existing transparency measures are applied, complied with, and enforced effectively.

Our analysis finds that, when it comes to process, UK parties do not report data consistently and frequently present information in an opaque way. Furthermore, we find that the content of disclosures is unclear, with existing activity classifications failing to capture the full spectrum of electoral activity. We also argue that the rules could be enforced more clearly in terms of the guidance the Electoral Commission provides when adjudicating on wrongdoing and/or sanctions. These findings are significant for understanding the requirements of an effective disclosure regime, but also suggest that even an apparently world-leading transparency system may not be providing effective information for voters or other election observers. Our analysis accordingly points to the need to revisit existing regulation to ensure that disclosures are able to cast light on the business of election campaigns.

The Appeal of Transparency: Accountability, Corruption and Trust

The idea of rendering information visible either directly to citizens, or indirectly through academia, civil society or the media, is a common response to uncover and/or prevent corrupt behaviour and more generally probe concerning practices in political systems (Berliner, Citation2014; Etzioni, Citation2010; Hood & Heald, Citation2006a; Stiglitz, Citation2002). In the context of elections, transparency has been cited as ‘the most important requirement’ of a ‘magic quadrangle’ (transparency, professional accounting, administrative practicality and the possibility of sanctions) that ensures the effective regulation of money in politics (Nassmacher, Citation2003, p. 139).

Reliable, informative, and systematic investigations rely on transparency. This overarching logic can be captured via the truism: ‘sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants’. This is the oft-quoted judgment by Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, in a 1913 Harper's Weekly article titled ‘What Publicity Can Do’. And yet, whilst these systems are widely established, our understanding of their effectiveness is somewhat underdeveloped. Whilst it is common to highlight countries exhibiting strong or weak practice (Mendilow & Phélippeau, Citation2018; Norris, Citation2017; Norris & Abel van Es, Citation2016), relatively little attention has been paid to examining the degree to which the strongest transparency regimes deliver meaningful insights. It can therefore often be unclear whether ‘good’ transparency systems are delivering information in line with democratic norms, and whether transparency regimes remain robust in the face of wider societal change. Such questions are vital for ensuring that disclosure continually delivers the stated desires of promoting accountability, reducing corruption, and increasing trust.

In the context of elections, transparency (or publicity) performs two functions. First, it is suggested that transparency promotes accountability and ensures that politicians are less likely to engage in unethical behaviour. By rendering information publicly available for scrutiny (either by voters themselves, or by actors working on their behalf), transparency offers an oversight mechanism, increasing the risk of engaging in malfeasance by increasing observations of their actions (Gerring & Thacker, Citation2004; Kunicová & Rose-Ackerman, Citation2005; Rose-Ackerman & Palifka, Citation2016). Given the rapidly evolving nature of campaigning practice, transparency in this context helps citizens to understand what campaign actions politicians are investing in. In turn this can help to disincentive expenditure on duplicitous activities and promote the idea of free and fair elections.

The second potential function of transparency is to increase trust in politics. Citizens, so the argument goes, gain a better knowledge of how politics works, and as such gain confidence in democratic institutions and the general functioning of democracy (Cain et al., Citation2001; Department for International Development, Citation2015; Ferraz & Finan, Citation2008; Pinto, Citation2009). For transparency to serve this function, however, it needs to be applied in such a way that information is brought to the citizenry – that ‘increasing transparency perceptions is more than just a website’ (Alessandro et al., Citation2021). However, some have cited the potential for a drip-feed of scandal to increase citizen distrust, apathy, and lead to a decline in participation in the form of, for example, lower turnout (Fisman & Golden, Citation2017, p. 209; Hough, Citation2013, p. 101). Others have suggested that transparency can simply confuse the public, and that reforms have a very limited overall effect on perceptions of government performance and, by association, trust (Grimmelikhuijsen, Citation2012; Grimmelikhuijsen et al., Citation2013; Licht, Citation2011) Despite these concerns, transparency is often seen to foster an informed citizenry who, through this increased understanding of the functions of government, trust the system to a greater degree (Cook et al., Citation2010; Hood & Heald, Citation2006b).

In this paper, we take the view that increased transparency (with caveats) is important despite the potential for a lack of trust in the system. Discussions about the effects of transparency often treat the concept as vague and capacious. Indeed, Dommett (Citation2020) has shown that there is imprecision in calls for transparency (i.e. it is often unclear what is actually desired, and how any stated impacts can be secured). Noting this tendency, we contend that it is not enough to simply say that a regime is transparent, or indeed, ‘effectively world leading’ (Power, Citation2020). Nor is it all that useful to suggest that transparency – in and of itself – is a remedy against corrupt practice. Instead, we should assess the process and content of existing disclosures, to better understand what information is being made transparent, and whether said disclosures perform their functions. In short, for transparency to be a successful legislative response, it needs to be applied, complied with, and enforced effectively. Only then can we begin to broach the question of how any desired impacts can be secured.

Case Study: The UK Political Finance Regime

Within this paper, we examine the system of financial transparency that surrounds the UK general election. This focus departs from a tendency to examine ‘bad’ cases (see for example Agbaje & Adejumobi, Citation2006; Daniels et al., Citation2020), and instead seeks to interrogate a system seen to be ‘world-leading’ (Power, Citation2020; see also GRECO, 2008; 2013) (in the tradition of, for example, Coglianese, Citation2009; Green, Citation2014).

The current regime, set out in the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (PPERA), is largely overseen by the Electoral Commission, whose website hosts a public archive and publishes spending returns. Whilst PPERA forms the legislative backbone of the political finance regime, legal principles – such as a cap on constituency spending – have actually been in place since the late nineteenth century, when they were laid out in the Corrupt and Illegal Practices (Prevention) Act 1883. PPERA also interacts with the Representation of the People Act 1983 (RPA). In sweeping terms party (i.e. national) spending is regulated under PPERA, and candidate (i.e. local/constituency) spending falls under the RPA. This leads to an electoral law that – according to the Law Commission (2016) – is out of date, complicated and fragmented. Interpreting the law, has been described as akin to ‘a Jane Austen-style intricate dance, where all sorts of daring and dicey moves are permissible, provided you know where to step when, and how not to upset the crowds’ (Ball, Citation2020). Nevertheless, this regime works to operationalise transparency from a normative ideal into a tangible reality (see Power, Citation2020).

The disclosure regime specifically provides information about resources and spending, and gathers data on any donations to a political party, non-party campaign or candidate. Information is also available about spending at elections by both parties and non-party (i.e. third parties) campaigners, with invoices or receipts for payments above £200 available for download from the public archive. Importantly for our purposes, unlike other equivalent spending regimes (such as the USA), the UK Electoral Commission make the invoices publicly available in an online database.Footnote1

Political parties, candidates, and non-party campaigners must all report any spend during election periods (up to 365 days before the election), and include invoices for anything over £200.Footnote2 These invoices are made available as pdfs on the public system – accessible through the UK Electoral Commission's website. As such it is possible to open each invoice and identify the service declared. At present, the information provided by parties about their electoral spending is classified under one of nine descriptive headings.Footnote3 These are: Advertising, Campaign broadcasts, Manifesto or referendum material, Market research/canvassing, Media, Overheads and general administration, Rallies and other events, Unsolicited material to electors and Transport. These headings provide a broad overview of the different kinds of activity that money is spent on. In addition, disclosures list the supplier who provided those services.

To address our research question, we consider three elements of the transparency regime. First, we explore the process through which disclosures are made, concentrating on the degree to which those providing information do so in a way that advances as opposed to frustrates understanding. Our analysis determines the degree to which transparency disclosures allow observers to understand the activity being paid for. Specifically, we find evidence of a range of barriers to insight, including a large number of unclear invoices which, for different reasons, inhibit transparency goals. Second, and building on this analysis, we consider the degree to which the activity classifications used within the existing Electoral Commission disclosure regime accurately capture the precise activity being paid for. Building on this analysis we make a further point relating to process. By comparing the categorisation of activity parties provide to the Electoral Commission (selecting from a predefined list of 10) with the description of activity within each invoice, we reveal inconsistencies in how the same activity is being declared. Collectively, these findings raise questions about the utility of the current disclosure regime. Third, we focus on the Electoral Commission itself, and consider potential issues with the way that the rules are enforced. In particular, we note a lack of clarity surrounding the mechanisms by which investigations are undertaken, and in the logic as to whether or not to engage sanctions.

Method

To achieve this, we examined spending returns for the 2019 general election. Specifically, we looked at national spend (as opposed to candidate spend), made by political parties (as opposed to non-party campaign groups). Adopting this focus, we identified 22,720 separate items of expenditure – inclusive of 6,396 invoices. In an initial sift we included only suppliers on which over £1,000 had been spent. This reduced the numbers of invoices we had to hand-code to 5,770, whilst still allowing us to analyse £49.9 m out of an overall £50 m (party) spend at the election.Footnote4

Opening each invoice in turn, we sought to inductively interpret the items of spending listed within each invoice. Where the information presented on an invoice was insufficient to identify the exact services which were being provided, we coded that invoice as ‘completely unclear’. Where a description was provided, we assigned an inductively generated code that captured the listed activity. Simple rules for coding were established, such as conducting exhaustive coding (i.e. coding each separate item mentioned in an invoice – meaning multiple codes could be assigned for one invoice) and non-duplicative coding (i.e. not assigning the same activity within an invoice more than one code).

To generate a consistent and encompassing list of codes, we worked as a team of four coders to formulate a new framework. Initially taking a sub-sample of our overall dataset, we each independently coded 200 items of expenditure to develop a list of codes. By comparing and contrasting the descriptors applied to the same invoices, we generated an initial list of categories. These were then applied to a second sample of 200 new invoices, and the consistency of coding was compared, with any disagreements discussed and reconciled in a 4-way conversation, and any new codes added as required. This process led us to identify a standard set of 50 categories (9 main codes, and 41 sub codes nested under these). This list was then used to classify the entire database (see Appendix 1). Each invoice was opened and coded by two coders. To check inter-coder reliability, we allocated approximately 20% of each coder's invoices to another team member to measure consistency. The Cohen's Kappa score for each pair of coders was at no point below К = 0.709, indicating a high degree of internal reliability.Footnote5

Findings

The Process of Electoral Campaigning Disclosure

In a world-leading transparency regime, the invoices provided to the Electoral Commission should contain sufficient information to allow classification of the type of activity money is being spent on. Only with such information can a transparency regime be enforced effectively. Within our dataset, however, we found that 755/5,770 (13.08%) of our invoices could not be coded. These invoices account for £6,628,924 (or 13.7 per cent) of total spend, making it unclear what over 1 pound in every 10 was spent on.

Looking in more detail at why invoices could not be coded, we identified a number of different reasons. In some instances, a code could not be assigned because it contained little information about the activity supplied. At times the description was incredibly vague, with an invoice for £60,000 listing simply ‘Provision of services’.Footnote6 Other invoices lacked a description,Footnote7 or exhibited formatting issues. Indeed, in one invoice the description of the service was obscured by a post-it note,Footnote8 and in others the scanned invoice was blurry or distorted.Footnote9 Other invoices could not be coded because of human error. For example, an item of spending may be listed in the Electoral Commission database but an invoice not uploaded (where required) and hence could not be categorized. Sometimes, a document linked to a blank page, and in some cases the wrong invoice had been submitted.

A final problem we encountered was with the system itself. Our process allowed us to delineate between types of spending from the same supplier. So, if a company provided multiple services (e.g. consultancy, campaign material printing and advertising) we could assign spend to each category. However, at present, a party submitting invoices can only select one of the pre-existing categories (e.g. overheads and general administration or advertising). In the case where a supplier provided multiple services, but where some of the spend was under £200, it was not possible for us to assess what service was provided.Footnote10 In these cases, spending could only be categorised as ‘unclear’. This was not an issue for those companies that provided only one service, as we could be reasonably confident that the services provided that were under £200, were the same as those invoiced for over £200.

The primary reason for a lack of clarity, was 219 invoices that were not uploaded by the Conservative Party regarding spending on Conservative Party Constituency Associations (all over £200). This apparently internal transfer of cash was not formally documented by the party, making it unclear what exact services they were paying Conservative Constituency Associations to perform (see also Bychawski, Citation2022).

We can unpick these trends further, by looking at the levels of spend by party, and the percentage of that spend which was classified as unclear. shows that the worst performer, by some distance was Plaid Cymru. All but two of the invoices they submitted were blank, such that no information could be gleaned about the service provided. Whilst total Plaid Cymru spend at the general election is dwarfed by the other parties, this shows exceedingly poor transparency compliance. Of the ‘big spenders’ (i.e. those parties that spent over £1 m), the Brexit/Reform Party and the Conservatives were the two that submitted the highest proportion of unclear invoices. To appreciate the impact of this behaviour it is useful to rely on levels of spend, as opposed to number of invoices/suppliers. As shown in , this meant that £1,291,487 (25.8%) of Brexit/Reform party spend and £3,683,578 (22.5%) of Conservative Party spend could not be accounted for. The Liberal Democrats had 138/374 (36.8%) suppliers where some form of spend could not be categorised, yet the total unclear spend was £404,110 (or 2.8% of total spend). On the other hand, Labour had just 42/263 (15.9%), where the total unclear spend was £1,159,863 (or 9.5% of total spend).

Table 1. Unclear spending as a percentage of total election expenditure.

This suggests that the existing system of disclosure does not always provide informative insights, and that parties are responsible (albeit to different degrees) for this lack of information. Given the apparent need for citizens and other observers to be able to gather information about the conduct of elections and electoral activity, our findings suggest that better enforcement action to compel informative disclosure needs to be taken against some actors to ensure more accurate information is available.

The Content of Disclosures

To consider our second aspect of the disclosure system, we focused on the degree to which provided invoices offer details about the kind of activity parties are paying for. This revealed important insights about content, but also further deficiencies in the process of disclosure. To gain this understanding we inductively coded the type of activity described in each invoice. Presenting our findings we, first, discuss the degree to which the existing disclosure regime is able to capture the activities we identified. We then compare our categories to disclosures made to the Electoral Commission to assess the consistency with which the Commission's present labels are being applied.

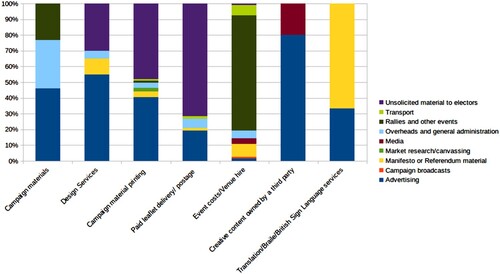

The Electoral Commission's invoice classification system makes it possible to gain a broad appreciation of the kind of activity that political parties spent money on at the 2019 general election (). This reveals the dominance of spending on unsolicited material to electors, advertising and market research. Indeed, 40.9 m (82%) of total campaign spend was classified under these three headings. Beyond this, however, these labels offer little information about the precise type of activity being conducted. It is unclear, for example, what form of unsolicited material or advertising is being paid for. In light of concerns about spending on, for example, potentially problematic forms of social media advertising, these data are relatively uninformative as it is not possible to determine the amount being spent on such advertising forms.

Table 2. Spend declared under each of the Electoral Commission's categories.

Whilst one can search the Electoral Commission database for specific providers – something the Electoral Commission itself did to determine social media advertising spend on Facebook, Google and other social media companies (Electoral Commission, Citation2018) – this information is limited as it does not capture social media advertising via third parties (Dommett & Power, Citation2019, Citation2022). For this reason we inductively coded the activity described within each invoice, producing 50 codes: 9 overarching categories and 41 subcategories (see Appendix 1 for a full table of categories and sub-categories). To gain an initial impression of the alignment of our categories with those proscribed in legislation to the Electoral Commission, we ranked each category by total spend classified under each heading ().

Table 3. Spend as categorized through our coding process.

Despite a difference in approach, there are some similarities between our inductive coding and parties’ own categorisation under the pre-existing categories. In particular the top two for both approaches are unsolicited material to electors and advertising (current approach) and campaign materials and advertising and press (our coding), which are broadly analogous. This suggests that the political finance database is (somewhat) adequately capturing the predominant form of spending at UK general elections. However, it is presently unclear what precise activities are being declared under these headings. This kind of insight can be gathered through our coding framework, and specifically through the sub-categories we identify.

A More Granular Insight

Underneath the 9 codes we identify, we outline 41 subcodes that provide significantly more insight into the kinds of activity parties spent money on at the 2019 election. presents the ten most commonly assigned sub-categories (not including unclear invoices) and offers more detail into what activities were conducted. Mirroring above findings, it shows that ‘traditional’ campaigning techniques dominate spending. Moving beyond this, however, it reveals that unsolicited material to electors, or what we term campaign materials involves expenditure on paid leaflet delivery and campaign material printing – with these two activities forming the bulk of spending (and therefore spending at the 2019 general election). Our analysis also advances understanding of what is being declared as advertising, revealing that social media advertising and online advertising were the dominant forms (featuring as the third and fifth within our top 10 spending categories), whilst newspaper and magazine advertising featured as the seventh most prominent spending subcategory. We also gain more insight into dominant forms of research, with polling featuring as the fourth largest spending category in our subcodes, whilst more generic research services were the eighth largest type of spending.

Table 4. Ten biggest areas of spend (not including unclear invoices) using our coding model.

Our data offers a better understanding of the types of activity being conducted as well as the relative prominence of each in terms of spend. Although this does not capture everything (as much campaigning can be done without incurring spend), it provides a useful indicator of the type of activity being conducted by parties in an attempt to win votes. We also suggest that our coding categories highlight a further issue with regards to the process of disclosure under the current regime. In essence, we suggest that by comparing our more detailed categorisation of supplier activity with the category chosen when an invoice is declared to the Electoral Commission, we can determine whether the current categories are being consistently applied. To these ends we consider the classification of invoices under our two top-spending categories (campaign materials and advertising and press), comparing each approach.

Consistency of Campaign Spending Disclosure Categorisation

As we have previously suggested, our campaign materials category is closely aligned to the category of unsolicited material to electors. However, what is presently unclear is whether these activities are declared consistently. To put it another way, are invoices relating to activities such as campaign material printing or design services always declared under the same category (which we would expect to be unsolicited material to electors)? To consider this question we examine the classification of each of our subcodes under this heading () against the Electoral Commission's classification ().

Table 5. Subcategories for the ‘campaign materials’ category.

Comparing our classifications, shows that parties are not coding the same activity (or rather activities described in invoices in similar terms) in a consistent way under the headings in the Electoral Commission's political finance database. Taking the generic heading first, we see activity we classify as campaign materials being recorded by parties as advertising, overheads and general administration and rallies and other events, with only a fraction being coded as unsolicited material to electors. In a similar manner, what we see to be invoices relating to design services are currently being declared as advertising, manifesto or referendum material, overheads and general administration and unsolicited material to electors. Although some categories are being more consistently coded – like paid leaflet delivery – where 71.46% (48/67 of entries) is coded as unsolicited material to electors, other categories are being assigned to invoices which we judge to be doing the same service.

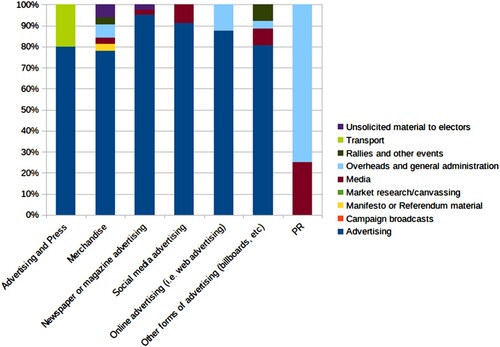

A similar finding emerges when we look in detail at spending declarations under the heading advertising and press, which is closely related to the category advertising in the political finance database. Our coding process identified 7 distinct activities under this heading ().

Table 6. Subcategories for the ‘advertising and press’ category.

Comparing the classification of these activities to the categories assigned to invoices in the Electoral Commission's political finance database (), we see less variance. This is especially in terms of the top three categories of social media advertising, online advertising and newspaper or magazine advertising. None of these dip below 85% in terms of level of agreement with the ‘advertising’ label in the political finance database. PR, on the other hand, is entirely captured by other labels, with advertising and press and merchandise falling at around 80% agreement.

These two categories are illustrative of broader trends we find within the entire dataset – political parties are not consistently declaring the same (or, rather, what our coding suggests to be the same) activity under one heading. It is therefore the case that payments are being classified inconsistently in disclosures to the Commission. Moreover, the current system of disclosure in the political finance database does not provide much granular detail about areas of concern. Returning to our central focus on transparency, a lack of consistent classification and important detail about what spending actually entails creates significant challenges for any attempt to identify any examples of campaign behaviour (problematic or otherwise), advance accountability and promote trust.

Investigating Enforcement

In the above we have assessed whether transparency measures are applied and complied with by parties, and have found significant deficiencies. However, this only provides a partial picture (on the supply side). The final question we ask is whether this transparency regime is enforced effectively by the Electoral Commission (on the demand side)? To do this we analysed the Electoral Commission's stated investigations into whether political parties properly disclosed their financial arrangements. In terms of campaign spending, the Electoral Commission may investigate a political party if they have failed to provide a complete and accurate account of spending. In other words, the Commission can enforce sanctions when political parties have been deemed to not apply and comply with transparency measures effectively.

The results of all investigations are published on the Electoral Commission’s website, inclusive of those related to campaign spending violations. After the 2019 general election 17 investigations were concluded between April 2020 and January 2023 relating to the reporting of campaign spending (see Appendix 3 for a detailed summary of investigations). Of these 17 investigations, the Electoral Commission was satisfied an offence had occurred in 12 (for 5 investigations there was either no offence committed, or no determination of an offence committed). In only 5 cases were sanctions applied (the largest being a £2,800 fine to Renew), and all 5 cases related to relatively minor political parties (Renew, Scottish Green Party, Gwlad, Mebyon Kernow, and the British National Party).

Moreover, as we have argued elsewhere (see Dommett et al., Citation2022, pp. 30–34) questions are outstanding with regards to how the compliance process works. Despite publishing guidance on its enforcement policy, it is unclear how judgements are arrived at. This is particularly as it relates to the threshold for investigation and when an offence is so serious that sanctions are applied. Indeed, in a wide-ranging review of electoral regulation, the Committee on Standards in Public Life (CSPL) suggested that the recipients of sanctions (whether parties or non-party campaigners) did not always understand why they had been subject to enforcement actions (The Committee on Standards in Public Life [CSPL], Citation2021, p. 126). And, as such, recommended that the Electoral Commission include much clearer explanations around enforcement and sanctioning of individual cases. We therefore find deficiencies in both the supply and demand side in terms of the UK transparency regime. On the supply side, parties do not always apply and comply with the current transparency measures. On the demand side, these rules are not always enforced effectively (or transparently), by the Electoral Commission.

Discussion

In light of the above findings, our analysis suggests that the UK's system of electoral finance disclosure as it relates to party spending at general elections displays a number of deficiencies. In ideal terms the information declared to the Electoral Commission should be applied and complied with properly, and enforced effectively. When this is the case, transparency is more likely to achieve its lofty aims of identifying and preventing corruption, advancing accountability and enhancing public trust. Our analysis has shown available data are not informative, and specifically we have highlighted two types of limitations within the returns that we describe as process and content issues.

First, in regards to process concerns, our analysis of the disclosure system has shown recurring issues with the way information is (or is not) provided. Specifically, our analysis found that £6.6 m of the spend reported to the Commission could not be scrutinized. We found instances of missing invoices, incorrect invoices, blurred invoices and many other practices which made it impossible to examine in detail what money was spent on (beyond using the current categories or making inferences based on supplier name). Whatever the cause of these unclear returns, they pose significant issues for attempts to understand and study elections. In addition, our own coding of available invoices revealed an inconsistency of how the same activity described in invoices was being declared under different headings by political parties. We therefore found that invoices relating to campaign material printing were classified as, for example, advertising or unsolicited material to electors. There accordingly appeared to be little coherence in the way that information is being provided, making it difficult to draw comprehensive or reliable insights from data in the public realm.

Second, in relation to the content of disclosure, our new coding model showed that it is possible to gain more detailed insight into the current activities parties are spending money on at elections. We can therefore use invoices to identify the specific types of activity being conducted and the relative prominence of each technique. Although helping to build up a picture of the dynamics of modern campaigns there are many questions which remain unanswered. An analysis of invoices can, for example, reveal social media advertising spend, but invoices do not reveal exactly which adverts were being bought, how these were targeted and what content they contained. Similarly, whilst we can identify consultants working for parties, invoices contain often at best limited information about the services they perform and the strategies they promote. When it comes to understanding the dynamics of modern election campaigning it is clear that there are many things we do not know, even in a world-leading disclosure regime.

These deficiencies are particularly problematic given the apparent goals of political finance transparency. As outlined at the outset of this article, transparency is seen to be a key tool for promoting democratic governance and is particularly seen to be a means by which to promote accountability, prevent corruption and enhance public trust. Our analysis has shown that the current disclosure system contains only limited information about political parties’ conduct at election campaigns. This means that it is difficult to envisage using this data to identify evidence of corruption and hold those responsible for problematic practices to account. Furthermore, it is not clear how this information would affect public trust as many questions remain about what exactly it is that parties are spending money on.

And yet, even these outcomes are uncertain. As our analysis has shown, the process of extracting insight from the political finance database is a time consuming and onerous affair. The prospect of individual citizens engaging in this kind of research is remote. This makes investigation by academics and journalists vitally important. That said, even if such efforts occur, the likelihood of findings cutting-through to inform public debate is slim as in a crowded media landscape, it is often challenging for all but the most sensationalized stories to gain coverage. Our analysis therefore raises fundamental questions about the degree to which the UK's system of electoral finance disclosure is not only informative, but also about its value within a democratic society. In essence, it is unclear who these transparency mechanisms are for, what they are trying to achieve, and whether the data can be used effectively to deliver desired goals?

In particular, it is unclear how this information is consumed by or likely to effect citizen attitudes, suggesting a need for further research to explore these themes (along the lines of, for example, vanHeerde-Hudson, Citation2011; vanHeerde-Hudson & Fisher, Citation2013). This might not simply be an issue for the UK, but raises wider questions about the conditions under which descriptive transparency – such as that we have outlined above – can increase trust in political processes. Indeed, prior research has pointed to the paradox that PPERA's transparency reforms may well have reduced corruption/increased accountability in UK politics – though this is hard to measure empirically – but had an inverse effect on public confidence (Fisher, Citation2002; Power, Citation2020). Sunlight may well be the best disinfectant, but is also illuminates what was once in the shade.

These slightly more existential reservations aside, we do suggest that there are a number of ways in which the current system of financial disclosure in the UK could be improved. In the first instance, these issues suggest a need for greater standardisation of practice in invoice disclosure. This recommendation mirrors existing calls for ‘standardized disclosure forms’ in the US (Heerwig & Shaw, Citation2014) or ‘common accounting practices’ in the UK (Power, Citation2020), that aim to reduce variation in the information released. While at present in the UK, the Electoral Commission (Citation2019, p. 27) states that invoices need to record ‘what the spending was for – for example, leaflets or advertising’, this research has shown that this is not followed and that there is not clear guidance for newer digital methods.

A standardized disclosure practice would also allow for the potential of adopting machine learning techniques for the analysis of invoices. At present invoices can come in almost any form, from broad (uninformative) handwritten receipts to forensically detailed breakdowns of precise spend. This makes it very hard to develop a successful machine learning model that can interpret these invoices. Other process-focused interventions could also be made. The Electoral Commission could provide increased guidance on the scope of disclosure categories – explicitly listing how invoices pertaining to particular activities should be classified. When it comes to content, more detailed descriptions could be required that allow observers to appreciate the precise activity money is being spent on. Whilst our recommendations focus on improving the current disclosure system, there is also potential to revisit the scope and timing of disclosures, with possible reforms such as an extended disclosure period and more instantaneous reporting additional considerations that regulators may wish to consider, but such steps should, we argue, only be taken once the deficiencies with the existing system have been addressed. Whilst not addressing the more fundamental questions about the impact and purpose of disclosure, we suggest that these changes could deliver valuable information.

Conclusion

In this paper we posed the question: ‘How informative is the UK's system of electoral finance disclosure as it relates to party spending at general elections?’. To answer this, we considered whether transparency measures are applied, complied with and enforced effectively. Analysing returns from political parties following the 2019 general election, we have argued that the current system of financial disclosure does not adequately meet the requirements of an effective transparency regime in terms of both process (i.e. how information is disclosed) and content (i.e. what information is disclosed). We have demonstrated this via an innovative coding model of the 5,770 invoices that political parties uploaded to the Electoral Commission's political finance database.

As it currently stands, voters can only reasonably expect to discover a limited amount of information – leaving it to journalists, academics and interested observers to fill in the gaps. Even then, there is a significant black box in terms of what we know about election spending. This is particularly as it relates to the process of disclosure. It is unclear how £6.6m at the 2019 general election was spent. Reform should focus on a review of the existing categories (which do not provide a full picture of election activity, particularly as it relates to data-driven campaigning) and advocating for a standardisation of invoicing to implement common accounting practices (for both political parties and non-party campaigns).Footnote11 This will allow for more immediate detail in terms of what services companies and suppliers are performing, and provide a genuine opportunity for machine learning and near real-time analysis of election spending returns. Beyond these changes, however, we suggest there is also a need for a more far-ranging re-examination of the goals and impact of transparency disclosure that considers when, how and in what form transparency informs citizens’ experience of modern elections.

Open Access

For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2024.2363526)

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sam Power

Sam Power is Senior Lecturer in Politics at the University of Sussex. His research focuses on political financing, electoral regulation and corruption.

Katharine Dommett

Katharine Dommett is Professor of Digital Politics at the University of Sheffield. Her research focuses on digital technology and democratic politics, with a particular focus on data use, election campaigns and regulation.

Amber MacIntyre

Amber MacIntyre is Project Lead in Data and Politics at Tactical Tech. She obtained her PhD at Royal Holloway, University of London and researches how data is used in political processes around the world.

Andrew Barclay

Andrew Barclay is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Oxford. His research focuses on elections and political engagement.

Notes

1 The Electoral Commission database can be found at http://search.electoralcommission.org.uk/Search/Spending?currentPage=1&rows=10&sort=DateIncurred&order=desc&tab=1&open=filter&et=pp&includeOutsideSection75=true&evt=ukparliament&ev=3696&optCols=CampaigningName&optCols=ExpenseCategoryName&optCols=FullAddress&optCols=AmountInEngland&optCols=AmountInScotland&optCols=AmountInWales&optCols=AmountInNorthernIreland&optCols=DateOfClaimForPayment&optCols=DatePaid

2 The rules at referendums are different and spending limits depend on the nature of the referendum itself, and whether the regulated entity is the lead or registered campaigner (though invoices must also be provided for spend above £200).

3 The category which is assigned to a given case of expenditure is the responsibility of the party when declaring their spending. This means that different parties procuring the same service (even from the same supplier) may be categorised differently on the Electoral Commission database.

4 We analysed £49,904,074.11, as compared with £50,057,203.83 – a deficit of £153,129.72

5 The full breakdown of the Cohen's Kappa scores can be found in Appendix 2.

6 For example see: http://search.electoralcommission.org.uk/Api/Spending/Invoices/65307.

7 For example see: http://search.electoralcommission.org.uk/Api/Spending/Invoices/67188; http://search.electoralcommission.org.uk/Api/Spending/Invoices/68473.

9 For examples see: http://search.electoralcommission.org.uk/Api/Spending/Invoices/64590; http://search.electoralcommission.org.uk/Api/Spending/Invoices/68079; http://search.electoralcommission.org.uk/Api/Spending/Invoices/71362.

10 Invoices are not provided for spend under £200.

11 The categories are set by PPERA so any reform would have to occur through further legislation.

References

- Agbaje, A., & Adejumobi, S. (2006). Do votes count? The works of electoral politics in Nigeria. African Development, 31(3), 25–44.

- Alessandro, M., Lagomarsino, B. C., Scartascini, C., Streb, J., & Torrealday, J. (2021). Transparency and trust in government. Evidence from a survey experiment. World Development, 138, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105223

- Ball, J. (2020, October 11). The re story of Cambridge Analytica. The Spectator. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/were-there-any-links-between-cambridge-analytica-russia-and-brexit-/ 01/07/2024.

- Berliner, D. (2014). The political origins of transparency. The Journal of Politics, 76(2), 479–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381613001412

- Bychawski, A. (2022). ‘Tory Party faces questions over £3.6 m unaccounted for in 2019 election’. Retrieved September 28, 2022, from https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/conservative-party-electoral-commission-2019-general-election/.

- Cain, P., Doig, A., Flanary, R., & Barata, K. (2001). ‘Filing for corruption: Transparency, openness and record-keeping’. Crime, Law and Social Change, 36(4), 409–25. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012242810420

- Coglianese, C. (2009)., ‘The transparency president? The Obama Administration and Open Government. Governance, 22(4), 529–44.

- Cook, F. L., Jacobs, L. R., & Kim, D. (2010). Trusting what you know: Information, knowledge, and confidence in social security. The Journal of Politics, 72(2), 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381610000034

- Dahl, R. (1989). Democracy and its critics. Yale University Press.

- Daniels, B., Buntaine, M., & Bangerter, T. (2020). Testing transparency. Northwestern University Law Review, 114(5), 1263–334.

- Department for International Development. (2015). ‘Why corruption matters: understanding causes and effects and how to address them. Retrieved September 28, 2022, from https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/why-corruption-matters-understanding-causes-effects-and-how-to-address-them

- Dommett, K. (2020). Regulating digital campaigning: The need for precision in calls for transparency. Policy & Internet, 12(4), 432–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.234

- Dommett, K., & Power, S. (2019). The political economy of Facebook advertising: Election spending, regulation and targeting online. The Political Quarterly, 90(2), 257–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12687

- Dommett, K., & Power, S. (2022). The business of elections: Transparency and UK election spending. Political Insight, 13(3), 12–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/20419058221127465

- Dommett, K., Power, S., MacIntyre, A., & Barclay, A. (2022). Regulating the business of election campaigns: Financial transparency in the influence ecosystem in the United Kingdom. International IDEA. Retrieved July 01, 2024, from https://www.idea.int/publications/catalogue/regulating-business-election-campaigns.

- Dommett, K., & Temple, L. (2018). Digital campaigning: The rise of Facebook and satellite campaigns. Parliamentary Affairs, 71(S1), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsx056

- Electoral Commission. (2018). Digital campaigning: Increasing transparency for voters.

- Electoral Commission. (2019). UK Parliamentary General Election 2019: Political Parties (GB & NI). Retrieved September 28, 2022, from https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/sites/default/files/2019-10/Political%20parties%202019%20UKPGE.pdf.

- Etzioni, A. (2010). Is transparency the best disinfectant? Journal of Political Philosophy, 18(4), 389–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9760.2010.00366.x

- Ferraz, C., & Finan, F. (2008). ‘Exposing corrupt politicians: The effects of Brazil’s publicly released audits on electoral outcomes’. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 703–45. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.2.703

- Fisher, J. (2002). Next step: State funding for the parties? The Political Quarterly, 73(4), 392–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.00493

- Fisman, R., & Golden, M. A. (2017). Corruption: What everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press.

- Forestal, J. (2022). Designing for democracy: How to build community in digital environments. Oxford University Press.

- Gerring, J., & Thacker, S. C. (2004). Political institutions and corruption: The role of unitarism and parliamentarism. British Journal of Political Science, 34(4), 295–330. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123404000067

- Gibson, R. (2015). Party change, social media and the rise of ‘citizen-initiated’ campaigning. Party Politics, 21(2), 183–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068812472575

- Gibson, R. (2020). When the nerds Go marching In: How digital technology moved from the margins to the mainstream of political campaigns. Oxford University Press.

- Green, R. (2014). Rethinking transparency in U.S. Elections. Ohio State Law Journal, 75(4), 779–828.

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S. (2012). A good man but a bad wizard. About the limits and future of transparency of democratic governments. Information Polity, 17(3–4), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-2012-000288

- Grimmelikhuijsen, S., Porumbescu, G., Hong, B., & Im, T. (2013). The effect of transparency on trust in government: A cross-national comparative experiment. Public Administration Review, 73(4), 575–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12047

- Heerwig, J. A., & Shaw, K. (2014). Through glass, darkly: The rhetoric and reality of campaign finance disclosure. Georgetown Law Journal, 102(5), 1443–1500.

- Hood, C., & Heald, D. (2006a). Transparency: The Key to better governance? Oxford University Press.

- Hood, C., & Heald, D. (2006b). Beyond exchanging first principles? Some closing comments. In C. Hood & D. Heald (Eds.), Transparency: The key to better governance? (pp. 211–226). Oxford University Press.

- Hough, D. (2013). Corruption, anti-corruption and governance. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Johnston, M. (1997). ‘Public officials, private interests and sustainable democracy: When politics and corruption meet’. In K. A. Elliot (Ed.), Corruption and the global economy (pp. 61–82). Institute for International Economics.

- Karlsen, R. (2013). ‘Obama’s online success and European party organizations: Adoption and adaptation of US online practices in the Norwegian labor party’. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 10(1), 158–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2012.749822

- Kefford, G. (2021). Political parties and campaigning in Australia. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kunicová, J., & Rose-Ackerman, S. (2005). Electoral rules and constitutional structures as constraints on corruption. British Journal of Political Science, 35(4), 573–606. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123405000311

- Lawson, K. (1980). Political parties and linkage: A comparative perspective. Yale University Press.

- Licht, J. (2011). Do we really want to know? The potentially negative effect of transparency in decision making on perceived legitimacy. Scandinavian Political Studies, 34(3), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2011.00268.x

- Magin, M., Podschuwejdt, N., Haßler, J., & Russmann, U. (2017). ‘Campaigning in the fourth age of political communication. A multi-method study on the use of Facebook by German and Austrian parties in the 2013 national election campaigns’. Information, Communication & Society, 20(11), 1698–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2016.1254269

- Mendilow, J., & Phélippeau, E. (2018). Handbook of political party funding. Edward Elgar.

- Nassmacher, K.-H. (2003). ‘Monitoring, control and enforcement of political finance regulation’. In R. Austin & M. Tjernstrom (Eds.), Funding of political parties and election campaigns: Handbook series (pp. 139–156). International IDEA.

- Nielsen, R. K. (2012). Ground wars: Personalized communication in political campaigns. Princeton University Press.

- Norris, P. (2012). Digital divide: Civic engagement, information poverty, and the internet worldwide. Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, P. (2017). Strengthening electoral integrity. Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, P., & Abel van Es, A. (2016). Checkbook elections? Political finance in comparative perspective. Oxford University Press.

- Pinto, J. (2009). ‘Transparency policy initiatives in Latin America: Understanding policy outcomes from an institutional perspective’. Communication Law and Policy, 14(1), 41–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10811680802577665

- Power, S. (2020). Party funding and corruption. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Rose-Ackerman, S., & Palifka, B. J. (2016). Corruption and government: Cause, consequences and reform. Oxford University Press.

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2002). On liberty, the right to know and public discourse: The role of transparency in public life. Global Law Review, 24(4), 263–73.

- The Committee on Standards in Public Life. (2021). Regulating election finance: A review by the committee on standards in public life. Retrieved July 01, 2024, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/60e460b1d3bf7f56801f3bf6/CSPL_Regulating_Election_Finance_Review_Final_Web.pdf.

- Tucker, J. A., Theocharis, Y., Roberts, M. E., & Barberá, P. (2017). From liberation to turmoil: Social media and democracy. Journal of Democracy, 28(4), 46–59. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0064

- vanHeerde-Hudson, J. (2011). Newspaper reporting and public perceptions of party finance in Britain: Knows little, learns something? Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties, 21(4), 473–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2011.609296

- vanHeerde-Hudson, J., & Fisher, J. (2013). Parties heed (With caution): public knowledge of and attitudes towards party finance in Britain. Party Politics, 19(1), 41–60. doi:10.1177/1354068810393268