?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Tolerance of others on grounds of race, ethnicity, nationality, religion and sexuality is an important component of social capital but has received scant attention in the social capital well-being literature. We examine the components of social capital and their relationship with life satisfaction using data from the Life in Transition Survey in European Union transition countries. A principal component factor analysis identifies three distinct and independent social capital components: tolerance, ties, and trust. Using a multilevel modelling approach, we estimate the relation between these components and life satisfaction, whilst controlling for individual and area effects. Tolerance, ties (networks) and trust are positively associated with life satisfaction.

1. Introduction

Intolerance of others on grounds of race, ethnicity, nationality, religion and sexuality is widely perceived as being on the rise over the past decade and some dimensions of intolerance have manifested into recent political instability, nationalism and populism across Europe (Wilson, Citation2016). The European integration project was developed largely as a reaction to the nationalistic excesses that led to World War II (Licata & Klein, Citation2002). However, the 2016 Brexit vote has highlighted the vulnerabilities of EU integration and the possibility that European citizenship breeds xenophobia or a cultural backlash (Abreu & Öner, Citation2020; Licata & Klein, Citation2002; Poutvaara & Steinhardt, Citation2018). Recent evidence suggests that the most important drivers of the Brexit leave vote were contextual cultural factors (Abreu & Öner, Citation2020), but others argue that rising populism in America has economic roots driven by stagnating wages, downward social mobility and rising hopelessness (Setterfield, Citation2020). As European societies continue to become more heterogeneous a greater understanding of intolerance is warranted. Moreover, questions remain as to whether intolerance manifests itself into individual general unhappiness thus exacerbating the aforementioned issues in EU countries.

Social capital is described as the value of social norms, networks and mutual trust to individuals and society (Coleman, Citation1988; Portes, Citation1998; Putnam, Citation2000). The relationship between social capital and well-being (happiness/life satisfaction) is well documented in the literature (Helliwell & Putnam, Citation2004) but less so the impact of tolerance on well-being. Tolerance is an important indicator of social cohesion and according to Inglehart (Citation1997, p. 188) flourishing societies require ‘a culture of trust and tolerance, in which extensive networks of voluntary associations emerge’. Putnam (Citation2000) has highlighted that due to the obvious links with trust and engagement in networks, from a theoretical standpoint tolerance is likely to be part of the bigger social capital picture. Existing literature examining the importance of tolerance for economic growth suggests that tolerance and an open attitude towards minorities have played a role in a country’s ability to flourish economically (Berggren & Elinder, Citation2012; Florida et al., Citation2008).

In this paper, we focus our attention on examining the relationship between tolerance (and social capital more generally) and life satisfaction in European Union transition countries. Almost three decades have passed since Europe’s former communist countries began their transition to full market economies. The dramatic transformations of these economies over that time have brought considerable change in governance, labour markets, privatisation and other institutional reforms (Roaf et al., Citation2014). Moreover, and despite the global financial recession, transition countries now appear to be catching up economically with their Western European counterparts (Guriev & Melnikov, Citation2018), and living standards for most have improved (Roaf et al., Citation2014). However, a consistent finding in the literature is evidence of a ‘happiness gap’ where individuals in transition countries report significantly lower levels of well-being than their counterparts in Western Europe, even when adjusting for similar individual income levels (Blanchflower, Citation2001; Blanchflower & Freeman, Citation1997; Easterlin, Citation2009; Guriev & Zhuravskaya, Citation2009; Rodríguez-Pose & Maslauskaite, Citation2012; Sanfey & Teksoz, Citation2007). However, results from a recent study indicate that the ‘happiness gap’ has closed on average, but remains for some groups in transition societies (Guriev & Melnikov, Citation2018; Obrizan, Citation2020). At the same time, the European Commission (Balázs et al., Citation2015) have expressed concerns around tolerance and cultural diversity in transition countries, despite three decades of democracy and over a decade of EU membership. In particular, social trust and trust in political institutions are low in transition countries and the Commission have identified concerns that these areas are not showing signs of improvement. They highlight that citizens of East Central Europe place a greater emphasis on economic development, respect for security and authority, but apathy to the freedom of expression and pluralism (Balázs et al., Citation2015). The OECD (Citation2011) and PEW (Citation2018) also identified Western and Eastern Europeans to differ on the importance of tolerance, religion, views of minorities and other key social issues. Others argue that the rapid transition undertaken by transition economies can lead to negative outcomes in the short run resulting in lower levels of social capital (Bennett et al., Citation2016). Against this backdrop, and the fact there is a dearth of research on the social capital well-being nexus for transition countries (Djankov et al., Citation2016; Guriev & Melnikov, Citation2018; Nikolova, Citation2016; Nikolova & Sanfey, Citation2016; Rodríguez-Pose & Maslauskaite, Citation2012), we believe this paper makes a timely contribution.

Existing research linking social capital and life satisfaction have used single countries to tell a subnational story and/or tend to focus on a particular aspect of social capital. For example, Awaworyi Churchill and Mishra (Citation2017) and Yip et al. (Citation2007) explore the relationship between elements of social capital and subjective well-being in China. Bjørnskov (Citation2008) empirically test the link between social capital and happiness in the US. Chang (Citation2009) find that levels of happiness increase with the accumulation of social capital in Taiwan. Papers that have explored the link between trust and well-being include (Bartolini et al., Citation2017; Glatz & Eder, Citation2020; Helliwell et al., Citation2018; Helliwell & Wang, Citation2011; Hudson, Citation2006; Kuroki, Citation2011). The importance of friendship ties to well-being is examined by Awaworyi Churchill and Smyth (Citation2020) using UK data, by van der Horst and Coffé (Citation2012) with data from Canada and by Requena (Citation1995) using Spanish and US data. In the context of these studies, we are motivated to examine the association between tolerance and life satisfaction using multi-country data from transition countries.

Some have argued for a greater understanding around the role of groupings, dynamics and configurations of local and national spatial environments in influencing a person’s overall well-being (Ballas & Tranmer, Citation2012; Bonnefond & Mabrouk, Citation2019; Lenzi & Perucca, Citation2016; Switek, Citation2012). This paper adds to that discussion by focusing on attributes of ‘place’ by including and controlling for country and regional random effects. In all, this enables the paper to explore the importance of social capital across space whilst also controlling for unique individual and place characteristics that may contribute to the well-being discourse on transition countries. We employ a multilevel ordered probit regression technique using almost 15,000 observations from 10 Central and Eastern European Union countries from the third Life in Transition Survey (LiTS).

2. Relevant literature and theoretical foundations

In this section, we introduce the concept of social capital and its most recognised components from the literature. After this, we argue that tolerance is a key component missing from the social capital paradigm in many studies and should be included when examining the social capital well-being nexus.

2.1. Defining social capital

The concept of social capital originated in the 1980s mainly through the work of Bourdieu (Citation1986) and Coleman (Citation1988). Bourdieu (Citation1986) conceptualised social capital as a resource that is connected with group membership and social networks, whereas Coleman (Citation1988) and Putnam (Citation1995) view social capital as the value of social norms of reciprocity, social networks and mutual trust and recognition. Social capital has been added to the categories of capital (physical, natural and human) in economic analysis (Sequeira & Ferreira-Lopes, Citation2011; Serageldin & Bank, Citation1996) and just like other forms of capital, it can be viewed as an accumulation of assets (social, psychological, cultural, cognitive, institutional and related assets) that yield benefit (Uphoff, Citation1999) or give people the capability to be and to act (Bebbington, Citation1999). It has individual benefits (Uphoff, Citation1999) and wider societal benefits which Coleman (Citation1988) likened to a public good that benefits society as a whole. It is suggested that regions that have well-functioning economic systems and high levels of political integration are more likely to be the result of the region’s accumulation of social capital (Putnam et al., Citation1993).

Since these earlier works, several similar definitions have been put forth to explain the concept of social capital, but no consensus definition has been agreed. This seems to be because social capital is a multi-dimensional concept that spans a multidisciplinary body of literature (Grootaert & Van Bastelaer, Citation2001). The parts that constitute social capital also remain unclear (Elgar et al., Citation2011; Nooteboom, Citation2007). However, a distinction is frequently made in the literature between networks (also commonly referred to as ties) and trust (Elgar et al., Citation2011; Inaba et al., Citation2015). We elaborate on this distinction next.

2.1.1. Personal ties

Personal ties and networks are considered to be structural social capital which relates to systems of social relations between people (Granovetter, Citation1973). It can include established networks and social groups, and their associated roles, rules, precedents and procedures that provide benefits to the individual as well as create positive externalities for communities. Structural social capital has been measured by the degree of participation in both formal networks (for example; business relations, community groups) and informal networks (friends/family) (Uphoff, Citation1999).

Granovetter (Citation1973) refers to two categories of structural social capital; namely strong and weak ties (also referred to as bonding and bridging social capital). The strength, whether considered strong or weak, of the relationship depends on how often contact was made with a tie. Strong ties (bonding social capital) are considered to be networks of family and close friends who interact frequently. Weak ties (bridging social capital) refer to the formation of links with acquaintances, colleagues or associates, for example (Granovetter, Citation1973; Putnam, Citation2000). These ties are weaker than bonding social capital but, according to Putnam (Citation2000), are more important for ‘getting ahead’. Moreover, weak ties can be considered to be connections between individuals and institutions or groups, for example, voluntary organisations. Sabatini (Citation2008) found weak ties may act as bridges across different communities allowing knowledge sharing and diffusion of trust. The OECD note that social connections are perhaps even more important for people in countries where formal organisations and institutions may be weaker (Boarini et al., Citation2014).

2.1.2. Trust

Trust is central to the concept of social capital and an extensive body of literature exists on the concept and measurement of trust as a component of social capital (Dasgupta, Citation2000; Glaeser et al., Citation2002; Mendoza-Botelho, Citation2013; Paldam, Citation2000; Uslaner, Citation1999). Also referred to as cognitive social capital, trust is associated with shared norms, values, attitudes, and beliefs that contribute to cooperation (Uphoff, Citation1999). In a measurable sense though, cognitive social capital has been proxied by the degree to which people trust others and the institutions around them (Pargal et al., Citation1999; Reid & Salmen, Citation2000). According to Fukuyama (Citation1995) trust is the expectation that arises within a community of honest and cooperative behaviour, as a result of commonly shared norms in that community.

Putnam et al. (Citation1993) and Putnam (Citation2000) propose that trust and reciprocity lead to more efficient societies. Knack and Keefer (Citation1997) find a significant relationship between aggregate trust and economic growth but that levels of trust and trustworthiness vary significantly across countries. Helliwell and Putnam (Citation2004) highlight that high levels of trust, where social networks are present, is often the mechanism through which social capital affects economic outcomes.

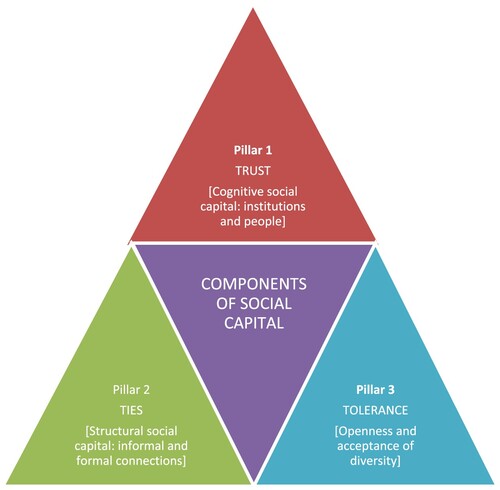

Next, we explore tolerance as a concept within the social capital nexus. We argue that this largely forgotten dimension be included as a distinctive component of social capital (see ), and hence we include it in our framework and empirical analysis that follows.

2.1.3. Tolerance

Tolerance is defined as respect for diversity or the ability to accept diversity (Cerqueti et al., Citation2013; Corneo & Jeanne, Citation2009). It can also mean ‘openness, inclusiveness and diversity to all ethnicities, races and walks of life’ (Florida, Citation2002, p. 10). Tolerant people exhibit diversified values and the capacity to respect differences in others (Corneo & Jeanne, Citation2009). It is seen as an important feature of modern society (Corneo & Jeanne, Citation2009), a distinguishing feature of Western culture (Berggren & Nilsson, Citation2016) and an important indicator of social cohesion (OECD, Citation2011). Higher levels of tolerance have potentially important outcomes for societies in terms of: economic growth (Jacobs, Citation1961); regional productivity (Ottaviano & Peri, Citation2005); technological and economic performance (Florida, Citation2002); entrepreneurial resilience (Huggins & Thompson, Citation2015) housing values, income (Florida & Mellander, Citation2010); and human capital and occupational skills (Florida et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, more open and diverse regions can lead to increased levels of innovation because they are likely to attract greater numbers of talented and creative people (Florida, Citation2002).

There are clear links between the concepts of tolerance, ties and trust. A culture of trust and tolerance, in which extensive networks of voluntary associations emerge are vital for flourishing societies (Conzo et al., Citation2017; Inglehart, Citation1997). At the individual level, the capacity to have high tolerance to diversity would act as a bridge (or the glue) for most people to trust, engage and network with others and with institutions. Tolerance of different beliefs and cultures stem from shared norms, values and attitudes. According to Florida (Citation2019) tolerance has been measured by incorporating key variables such as; the share of immigrants or foreign-born residents, gay and lesbian Index, and the Integration Index which tracks the level of segregation between ethnic and racial groups (Florida, Citation2019; Mellander et al., Citation2012).

2.2. Subjective well-being and social capital

The understanding of well-being is underpinned by a diverse body of existing literature across a range of disciplines including economics, psychology and sociology (Diener et al., Citation1999; Dolan et al., Citation2008; Kroll, Citation2011). The WHO (Citation2012) defines it as comprising of an individual’s experience of their life as well as a comparison of life circumstances with social norms and values. Subjective well-being refers to all of the various types of evaluations, both positive and negative, that people make of their own lives and can include evaluations of life satisfaction, good psychological functioning, and emotions such as; happiness, joy and sadness (Diener, Citation2006; OECD, Citation2013). Although various measures of subjective well-being exist, this paper uses self-reported life satisfaction which is taken to mean enduring satisfaction with one’s life-as-a-whole (Veenhoven, Citation2015).

Much of the existing literature suggests that individuals’ well-being is positively affected by high levels of trust. Bjørnskov (Citation2006) found that of the components of social capital, as measured by generalised trust, social norms and volunteering associations, the effects of social capital on well-being seem to be mainly driven by social trust. As well as individuals’ levels of trust, trust in governments have been found to be positively related to life satisfaction (Bjørnskov et al., Citation2010; Helliwell, Citation2006; Helliwell & Huang, Citation2008; Helliwell & Putnam, Citation2004). Taking data on transition countries, Bartolini et al. (Citation2017) find that social trust is correlated with well-being in the medium-term but not in the short-term. Helliwell et al. (Citation2014) examine 10 transition and 20 non-transition economies between 2006 and 2010 and suggest that social trust has a significant impact on life satisfaction in transition countries but not in non-transition countries. Mikucka et al. (Citation2017) use a single measure of social trust and find that that in the long-run social capital is a major predictor of life satisfaction in transition countries. Veenhoven (Citation2015) suggest that social relations (both primary ties in an individual’s private life and their secondary relations in public life) explain differences in life satisfaction. Inaba et al. (Citation2015) find support for a positive effect of both structural and cognitive social capital on life satisfaction. Helliwell (Citation2006) finds that the intensity of social links in the form of higher contact with family and friends leads to higher levels of life satisfaction.

The link between well-being and levels of tolerance has been less explored in the existing literature, although Inglehart et al. (Citation2008) find that more tolerant societies reported higher levels of aggregate well-being and Inglehart et al. (Citation2013) argue that research has underscored the important links between tolerance and well-being. Freedom of choice, gender equality, and increased tolerance is linked to a considerable rise in overall world happiness (Inglehart et al., Citation2008).

A large body of existing work confirms that individual and socio-economic determinants such as; personality, income, age, gender, employment, marital status, and education are also important in explaining life satisfaction levels (see Dolan et al. Citation2008). Vast differences in life satisfaction across European regions exist and both national and regional level variations in well-being have been investigated in the existing literature. Frey and Stutzer (Citation2000), Helliwell (Citation2006), Bjørnskov (Citation2008) for example find significant differences between regions within countries. Research has also investigated the impact of community characteristics on well-being (Farrell et al., Citation2004). However, some have highlighted that there has been a lack of research on individual well-being from a regional science or spatial perspective (Ballas & Tranmer, Citation2012; Lenzi & Perucca, Citation2016; Switek, Citation2012).

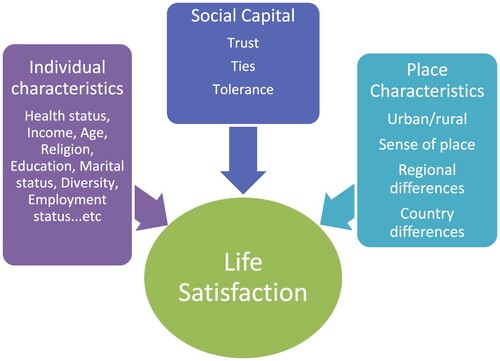

Consequently, our framework incorporates the need to account for social capital indicators, individual characteristics and place-specific characteristics in estimating the determinants of life satisfaction, as outlined in .

Figure 2. Framework linking social capital, individual characteristics and place characteristics to life satisfaction.

By investigating the components of social capital (), we contribute to the empirical literature by identifying if tolerance is a component of social capital and secondly, by exploring a more comprehensive framework of life satisfaction that incorporates both individual and place effects (). We now proceed to the empirical contribution of the paper, where the data and methods used to examine the facets of our framework are outlined.

3. Data and methodology

The data used in this study stems from the Life in Transition Survey (LiTS) III. The LiTS III asks respondents their views on issues such as democracy, the role of the state and their prospects for the future. It also contains detailed data on the household and individual characteristics of respondents. The data used in this analysis are from the primary respondent in each of the LIT survey household responses. The data was collected in 2016 and it polled 51,000 households in over 34 countries. It consists of data from advanced and transition economies and has been utilised previously in life satisfaction studies (Nikolova & Sanfey, Citation2016). To reduce country and institutional heterogeneity, we only include the European Union countries that were previously command led economies: Slovenia, Slovakia, Romania, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Hungary, Estonia, Czech Republic and Croatia. The sample of households from each country was approximately 1,500, collected by stratified random sampling techniques, representing a combined sample size of 14,897 for the analysis.

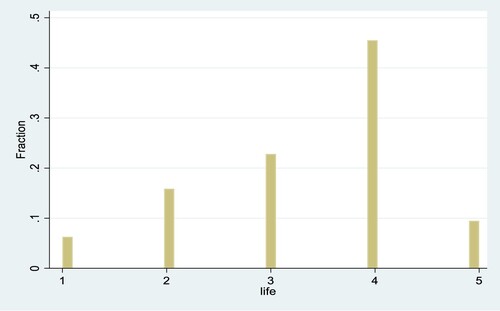

Self-reported levels of life satisfaction are widely used in the well-being discourse as indicators to measure subjective well-being (Kahneman & Krueger, Citation2006) and have been found to be valid and reliable measures (Helliwell & Putnam, Citation2004; Stiglitz et al., Citation2009). Our dependent variable is measured by the principal household respondent’s judgement of their life satisfaction. Specifically, the question asked, ‘All things considered, I am satisfied with my life now’. The distribution of this variable is visually presented in . The variable is on a Likert scale ranging in values from 1 to 5 (strongly disagree – strongly agree). The average life satisfaction across the sample countries was 3.36.

Figure 3. Distribution of life satisfaction ‘All things considered I am satisfied with my life now’.

To examine any possible association between social capital and life satisfaction, we need to configure appropriate measurements of social capital and its components. Clarity on the definition, measurement and different classifications of social capital is far from complete (Saukani & Ismail, Citation2019). Like human capital, social capital is difficult to measure directly, and proxy indicators are employed when examining its influence on economic phenomena. The data employed to configure measures of social capital are generally qualitative and in nominal or ordinal form (Saukani & Ismail, Citation2019). In the theoretical section, we argued that there are three independent components of social capital: personal ties, trust and tolerance. We employ the use of a combination of factor and principal component analysis (PCA) to investigate which social capital indicators load highly on a specific factor and also to identify if latent dimensions represented in the variables exist which helps us explore our a-priori expectations.

Our approach blends the two procedures of factor analysis and principal component analysis (which we refer to as PCA from here)Footnote1 (Mooi et al., Citation2018). The PCA method estimates linear combinations of underlying variables (), which in this case are indices of identified social capital indicators () that explain the highest possible fraction of the remaining variance in the dataset (Bourke & Crowley, Citation2015; Laursen & Foss, Citation2003). The principal components are estimated in steps, where the first component explains the highest possible fraction of total variance, the second explains the highest possible fraction of total variance unexplained by the first and each following component is estimated by this procedure until the explained residual variance is maximised. Finally, the components are rotated which allows for interpretation of the factors estimated (Mooi et al., Citation2018). The social capital indicators (in ) have discrete outcomes. The PCA method is based on a matrix of Pearson’s correlations which assumes the variables to be continuous and have a multivariate normal distribution. Consequently, we employ a polychoric correlation matrixFootnote2 to overcome this problem to ensure the variables are ‘smooth’ (see Bourke and Crowley (Citation2015) for more details on this approach) and are suitable for PCA analysis.

Table 1. Variable descriptions and summary statistics of indicators used in social capital factor analysis.

Table 2. Factor loadings for social capital indicators: trust, ties and tolerance.

Initially, a measure of sampling adequacy (MSA) was conducted on the data to ascertain the inclusion of the chosen variables in a PCA method. The meeting friends and family variable and the trust variable related to ‘friends’ had MSA values well below the acceptable threshold of 0.50 (Kaiser, Citation1974). These variables were subsequently removed from the analysis. We consider for theoretical reasons the meeting friends and family variable to be an important indicator of structural social capital (informal ties) and hence include it in the overall regression as a standalone and separate measure from the PCA analysis. We rerun the PCA after removing these two variables and estimate a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy on the remaining 32 indicators to identify if we can interpret our PCA results with confidence. The KMO value is 0.77. A value less than 0.50 is considered unacceptable (Kaiser, Citation1974; Mooi et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, a Bartlett test of sphericity indicates that the variables are significantly intercorrelated. We determine the number of factors to retain using the scree plot method (Cattell, Citation1966) and from the scree plot in Figure A1 (Appendix) it can be determined that there is a distinct break in the data at four factors. From this, we conclude that three factors are appropriate to retain as it is generally recommended that all factors should be retained above this break (Mooi et al., Citation2018) which explain 57 per cent of the overall variance.Footnote3

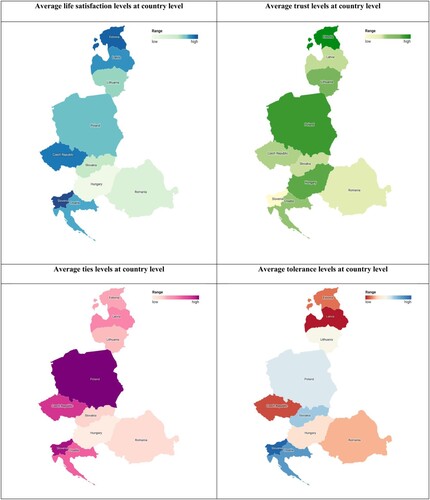

It is clear from the measures taken and factor loading analysis presented in that our theoretical argument that trust, ties and tolerance are three distinct social capital components holds. Interestingly, when the average values for the social capital indicators and for life satisfaction are mapped across countries (), there is a lack of a correlation between the measures across the sampled countries. For example, Slovenia has the highest average life satisfaction levels but the lowest trust capital levels. Similarly, Hungary does not score highly on life satisfaction at the aggregate level, but the respondents in Hungary did report high aggregate average levels on ties and tolerance.

Existing studies find significant differences with respect to life satisfaction between regions within a country (Bjørnskov, Citation2008; Frey & Stutzer, Citation2000, Citation2002; Rampichini & Schifini d'Andrea, Citation1998). Our dataset comprises three levels of observations, where households are nested within regions and regions are nested within countries. Multilevel modelling can account for the interdependence of life satisfaction observations at different nested levels by partitioning the total variance into different components of variation at the household, region and country level (Ballas & Tranmer, Citation2012; Goldstein, Citation2011).

The multilevel ordered probit model to be specified in this paper is outlined in Equation (1).

(1)

(1)

In this specification, notation

refers to the respondent in the household,

refers to the region and

refers to the country, the respondent is located.

are the observed ordinal responses and are generated from the latent continuous responses. Trust, Ties and Tol refer to the factor component measures of trust, ties and tolerance, respectively.

represents the individual level fixed effects.Footnote4

represents the random effects at the levels of country (10 countries) and region (101 regions where regions are the local administrative region for the respondent). Definitions and descriptive statistics of all control variables are presented in . As explained earlier, the dependent variable accounts for the extent of agreement with a view. It is thus measured on a Likert scale of five possible options, from 1 to 5 (low to high life satisfaction).

Table 3. Summary statistics of variables.

The problems of endogeneity and reverse causality have also been identified as possible methodological concerns in the empirical literature examining the link between social capital and well-being and particularly with cross-sectional data (Bonnefond & Mabrouk, Citation2019; Helliwell & Putnam, Citation2004). Consequently, we focus on the associations between social capital and life satisfaction in our analysis ().

Table 4. Multilevel ordered probit model of life satisfaction.

4. Results

The fixed effects results of the multilevel ordered probit model are displayed in and the marginal effects of this model are presented in Table A2 of the Appendix.Footnote5 Given the cross-sectional nature of the data we focus on the association between life satisfaction and social capital and other explanatory variables, rather than ascertaining any causal relationships.

We argued in the theoretical section that tolerance is an important social capital component that has not received the attention it should in the social capital well-being literature. We identify that more tolerant people are associated with higher levels of life satisfaction. The results further show evidence of a positive, significant association between trust and life satisfaction.

The results also show a positive association between life satisfaction and regular meetings with family and friends (informal ties). This significant association would appear to suggest that indicators on strong ties or bonds and life satisfaction are positively related. This is not surprising as friends and family can provide companionship, intimacy, support and reciprocity (Amati et al., Citation2018; Demır & Weitekamp, Citation2007). Similarly, the strength of weak ties (formal ties) is also found to be significant, where individuals with higher levels of weak ties are associated with higher levels of well-being.

Additionally, the importance of weak ties may be important for business and entrepreneurial capacity and hence the importance of weak ties may also enter the equation of well-being in an indirect way through income and/or job-type. The results also indicate that income and being an employer are positively associated with life satisfaction. However, being an employee is associated with lower levels of life satisfaction relative to a ‘not working’ status. Unemployment is also negatively associated with life satisfaction. In line with much of the literature to date we find that an individual’s health status, their gender, their marital status and their education are associated with life satisfaction. Interestingly, being a non-ethnic minority is negatively associated with life satisfaction. The relationship between age and well-being also exhibits evidence of a polynomial type U-shaped relationship which is a finding strongly supported by existing literature (Blanchflower, Citation2010; Blanchflower, Citation2021; Blanchflower & Oswald, Citation2008; Clark & Oswald, Citation1994; Steptoe et al., Citation2015).

Overall, there is a small (9 per cent) but significant proportion of the variation of life satisfaction attributable to country and regional levels (see ). Consequently, a larger variation in life satisfaction is associated with individual characteristics and spatial effects. However, it is important to note that some of the individual effects also involve place interactions, for example, our main social capital variables of interest, namely tolerance, ties and trust, arguably would heighten the overall contribution of place to influencing an individual’s overall life satisfaction assessment.

Table 5. Residual intraclass correlation.

We now return to our main variables of interest. Considering the social capital indicators are latent variables of a host of underlying components, it is not possible to determine the unit change. Consequently, the marginal relationships between them and an individual’s life satisfaction are unknown. To get an indicative sense of the size correlations, we estimate auxiliary models with the original components, instead of the factor variables. For the auxiliary models, a multilevel ordered probit model and multilevel linear regression are estimated. For interested readers, the marginal effects of these models are reported in Table A4 in the Appendix. It is important to take a couple of factors into consideration when reflecting on the size of the social capital component correlations. Firstly, the binary nature of the individual components means the underlying structure, spectrum and culminating nature of the latent factor variable are lost. Secondly, the individual components of the auxiliary model are intercorrelated with one another and so the correlation coefficients are likely to be biased. Finally, it is notable that broadly, in all models, the marginal correlations associated with many of the variables are small, but at the same time, the number of different factors related to life satisfaction is large. This pattern reinforces the multidimensional nature of well-being and its complex relationship with many individual, community, and regional indicators.

5. Conclusion

Our main objective in this paper was to identify if tolerance was an important component to consider in the social capital well-being relationship. We argued that tolerance should be identified as an independent component in the social capital paradigm as it is distinct from other social capital measures. The results from our principal factor component analysis indicated that this is a valid proposition as it identified three separate, distinct and lowly correlated factor components of trust, ties and tolerance. Further, we concluded from our multilevel analysis that being a tolerant individual is associated with higher levels of life satisfaction. We are not surprised by this finding as we expect increased personal tolerance to enable more social diverse interaction, a greater sense of openness and inclusivity, and consequently should be related to higher overall general well-being. The evidence presented here suggests that the component of tolerance should be considered in future social capital studies and in surveys aiming to collect data on social capital indicators.

The well-being literature on transition countries has identified a ‘happiness gap’ between older and younger (i.e. transition) European Union members. The European Commission have identified a further social capital gap between these two bodies of members in the European Union. The association between social capital and life satisfaction as evidenced in this paper may help to explain why the ‘happiness gap’ exists. The findings build a strong rationale for why the European Union should invest in building social capital focusing on trust, tolerance and informal ties because the link with well-being is clear. Individuals that engage with others, are open, tolerant and trusting of one another and the institutions that shape their environment, tend to display higher levels of satisfaction with life, in transition countries. The call for government intervention in social capital investment is certainly not new, for instance, Glaeser (Citation2001) argued that the rationale for government intervention is strong considering ‘the combination of positive externalities and complementarity leads to strong gains from co-ordinating investment’ (p. 37). Further, our results indicate that the distribution of social capital across individuals varies considerably from one person to another and between and within countries. This indicates that there may be some societal barriers to accessing social capital or at least it is poorly distributed across society.

The conundrum remains in a world of scarce resources whether it would be wise to offset government interventions that target ‘harder’ determinants like individual income and employment benefits vis-à-vis interventions that target ‘softer’ determinants like social capital. This is a difficult question to answer as it relies on knowing an unknown counterfactual. But do governments want to take the risk of not investing in social capital? Since societal capital plays a significant role in shaping institutional change, policymakers need to remain vigilant to the potential effects it may have in influencing long-run well-being levels. Societies that make weak investments in social capital may be more politically unstable or more susceptible to intolerant, distrusting and discontented societies leading to a rise in populist movements that could further erode trust, tolerance and ties in societies. Recent global events such as Brexit, the American elections and the yellow vest protests suggest we live in a politically unstable, potentially intolerant and bitter world (Poutvaara & Steinhardt, Citation2018). Our findings indicate that this could be particularly true for European Union transition countries.

Whilst we found that much of life satisfaction is associated with individual characteristics, it is also clear that regional and country effects matter for individual life satisfaction. Our analysis indicates the importance of employing an individual level-based analysis, whilst controlling for spatial concerns. Future studies need to ensure they account for both individual and place effects.

A limitation of the study is the cross-sectional nature of the data meaning that we can only determine associations between life satisfaction and the explanatory variables employed in our model and not causal links. Future research needs to focus on unlocking this long-term concern in the social capital well-being literature (Helliwell & Putnam, Citation2004; Portela et al., Citation2013).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (48.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The replication data developed from the Life in Transition Survey (LiTS) III described in the paper, is available online at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SOTRDJ, Harvard Dataverse.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Frank Crowley

Frank Crowley is a lecturer in Economics and Director of the Spatial and Regional Economics Research Centre at Cork University Business School, University College Cork. His primary research interests are in innovation, enterprise development and regional and urban development.

Edel Walsh

Edel Walsh is a lecturer in the Department of Economics, Cork University Business School, University College Cork. Her research area is health economics, specifically well-being determinants, health inequalities and ageing populations.

Notes

1 STATA’s factor, pcf command is used.

2 We use the user-written command polychoric in STATA 15.

3 Alternatively, if we apply the Kaiser criterion and retain all factors with eigenvalue over 1, seven factors will be retained explaining 74 per cent of the overall variance. The factor loading breakdown for these is provided in Appendix Table A1. Here, it can be identified that factor 1 relates to measures of formal ties, factor 2 relates to measures of trust particularly for political and economic institutions, factor 3 relates to measures of tolerance and factors 4–7 relate to other various combinations of trust indicators. If these factor scores are generated instead, the general results that are presented later in the paper are robust to these alternative factors, i.e. the factors exhibiting all these measures are significant and positive (except for factor 7). These results are presented in the supplemental documentation Table A5 in Appendix. In summary, the number of factors either three or seven does not matter for the overall general conclusions. It should also be noted that the Kaiser criterion is known for over specifying the number of factors (Mooi et al., Citation2018) and this is why we rely on both the screeplot and theoretical reasoning for deciding to constrain the factor analysis to three factors as factors 1, 2 and 3 are loaded heavily by all the components included and in the order of ties, trust and tolerance indicators respectively.

4 A sensitivity analysis was completed with a different continuous Log of income indicator. It is not reported as there were missing values with this variable. The results of income were robust. A correlation matrix of our variables indicates that there are no multicollinearity concerns present in our data. This table is not reported but can be obtained from the authors.

5 Previous literature have also estimated linear versions of ordinal dependent variables (Ferrer-I-Carbonell & Frijters, Citation2004). We also report the multilevel linear version of this estimation which can be viewed by interested readers in Appendix A3.

References

- Abreu, M., & Öner, Ö. (2020). Disentangling the Brexit vote: The role of economic, social and cultural contexts in explaining the UK’s EU referendum vote. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(7), 1434–1456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20910752

- Amati, V., Meggiolaro, S., Rivellini, G., & Zaccarin, S. (2018). Social relations and life satisfaction: The role of friends. Genus, 74(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-018-0032-z

- Awaworyi Churchill, S., & Mishra, V. (2017). Trust, social networks and subjective wellbeing in China. Social Indicators Research, 132(1), 313–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1220-2

- Awaworyi Churchill, S., & Smyth, R. (2020). Friendship network composition and subjective well-being. Oxford Economic Papers, 72(1), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpz019

- Balázs, P., Bozóki, A., Catrina, Ş., Gotseva, A., Horvath, J., Limani, D., Radu, B., Simon, Á., Szele, Á., Tófalvi, Z., & Perlaky-Tóth, K. (2015). 25 years after the fall of the iron curtain: The state of integration of East and West in the European Union. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Ballas, D., & Tranmer, M. (2012). Happy people or happy places? A multilevel modeling approach to the analysis of happiness and well-being. International Regional Science Review, 35(1), 70–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160017611403737

- Bartolini, S., Mikucka, M., & Sarracino, F. (2017). Money, trust and happiness in transition countries: Evidence from time series. Social Indicators Research, 130(1), 87–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1130-3

- Bebbington, A. (1999). Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Development, 27(12), 2021–2044. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00104-7

- Bennett, D. L., Nikolaev, B., & Aidt, T. S. (2016). Institutions and well-being. European Journal of Political Economy, 45(Suppl), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2016.10.001

- Berggren, N., & Elinder, M. (2012). Is tolerance good or bad for growth? Public Choice, 150(1), 283–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-010-9702-x

- Berggren, N., & Nilsson, T. (2016). Tolerance in the United States: Does economic freedom transform racial, religious, political and sexual attitudes? European Journal of Political Economy, 45(Suppl), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2016.06.001

- Bjørnskov, C. (2006). The multiple facets of social capital. European Journal of Political Economy, 22(1), 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2005.05.006

- Bjørnskov, C. (2008). Social capital and happiness in the United States. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 3(8), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-008-9046-6

- Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. V. (2010). Formal institutions and subjective well-being: Revisiting the cross-country evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 26(4), 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2010.03.001

- Blanchflower, D. (2010). International evidence of well-being. In A. Krueger (Ed.), Measuring the subjective well-being of nations (pp. 155–226). University of Chicago Press.

- Blanchflower, D. G. (2001). Unemployment, well-being, and Wage curves in Eastern and Central Europe. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 15(4), 364–402. https://doi.org/10.1006/jjie.2001.0485

- Blanchflower, D. G. (2021). Is happiness U-shaped everywhere? Age and subjective well-being in 145 countries. Journal of Population Economics, 34(2), 575–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00797-z

- Blanchflower, D. G., & Freeman, R. B. (1997). The attitudinal legacy of communist labor relations. ILR Review, 50(3), 438–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979399705000304

- Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2008). Is well-being U-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science & Medicine, 66(8), 1733–1749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.030

- Boarini, R., Kolev, A., & Mcgregor, A. (2014). Measuring well-being and progress in countries at different stages of development: Towards a more universal conceptual framework. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

- Bonnefond, C., & Mabrouk, F. (2019). Subjective well-being in China: Direct and indirect effects of rural-to-urban migrant status. Review of Social Economy, 77(4), 442–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2019.1602278

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). Forms of capital. Greenwood Press.

- Bourke, J., & Crowley, F. (2015). The role of HRM and ICT complementarities in firm innovation: Evidence from transition economies. International Journal of Innovation Management, 19(05), 1550054. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919615500541

- Cattell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1(2), 245–276. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10

- Cerqueti, R., Correani, L., & Garofalo, G. (2013). Economic interactions and social tolerance: A dynamic perspective. Economics Letters, 120(3), 458–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.05.032

- Chang, W. (2009). Social capital and subjective happiness in Taiwan. International Journal of Social Economics, 36(8), 844–868. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290910967118

- Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1994). Unhappiness and unemployment. The Economic Journal, 104(424), 648–659. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234639

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94(Suppl), S95–S120. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2780243

- Conzo, P., Aassve, A., Fuochi, G., & Mencarini, L. (2017). The cultural foundations of happiness. Journal of Economic Psychology, 62, 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2017.08.001

- Corneo, G., & Jeanne, O. (2009). A theory of tolerance. Journal of Public Economics, 93(5-6), 691–702. Retrieved from https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:pubeco:v:93:y:2009:i:5-6:p:691-702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.02.005

- Dasgupta, P. (2000). Economic progress and the idea of social capital. The World Bank.

- Demır, M., & Weitekamp, L. A. (2007). I am so happy ’cause today I found my friend: Friendship and personality as predictors of happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(2), 181–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9012-7

- Diener, E. (2006). Guidelines for national indicators of subjective well-being and ill-being. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 7(4), 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9000-y

- Diener, E., Suh, E., Lucas, R., & Smith, H. (1999). Subjective wellbeing: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276

- Djankov, S., Nikolova, E., & Zilinsky, J. (2016). The happiness gap in Eastern Europe. Journal of Comparative Economics, 44(1), 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2015.10.006

- Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(1), 94–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2007.09.001

- Easterlin, R. A. (2009). Lost in transition: Life satisfaction on the road to capitalism. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 71(2), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2009.04.003

- Elgar, F. J., Davis, C. G., Wohl, M. J., Trites, S. J., Zelenski, J. M., & Martin, M. S. (2011). Social capital, health and life satisfaction in 50 countries. Health & Place, 17(5), 1044–1053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.06.010

- Farrell, S. J., Aubry, T., & Coulombe, D. (2004). Neighborhoods and neighbors: Do they contribute to personal wellbeing? Journal of Community Psychology, 32(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10082

- Ferrer-I-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00235.x

- Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class. The Washington Monthly, 34(005), 15–25. https://washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/may-2002/the-rise-of-the-creative-class/

- Florida, R. (2019). The rise of the creative class revisited. Basic Books.

- Florida, R., & Mellander, C. (2010). There goes the metro: How and why bohemians, artists and gays affect regional housing values. Journal of Economic Geography, 10(2), 167–188. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:oup:jecgeo:v:10:y:2010:i:2:p:167-188. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbp022

- Florida, R., Mellander, C., & Stolarick, K. (2008). Inside the black box of regional development--human capital, the creative class and tolerance. Journal of Economic Geography, 8(5), 615–649. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn023

- Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2000). Happiness, economy and institutions. The Economic Journal, 110(466), 918–938. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00570

- Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics: How the economy and institutions affect human wellbeing. Princeton University Press.

- Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. Free Press.

- Glaeser, E. L. (2001). The formation of social capital. ISUMA, Canadian Journal of Policy Research, 2, 34–40.

- Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D., & Sacerdote, B. (2002). An economic approach to social capital*. The Economic Journal, 112(483), F437–F458. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00078

- Glatz, C., & Eder, A. (2020). Patterns of trust and subjective well-being across Europe: New insights from repeated cross-sectional analyses based on the European social Survey 2002–2016. Social Indicators Research, 148(2), 417–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02212-x

- Goldstein, H. (2011). Multilevel statistical models (Vol. 922). Wiley.

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2776392. https://doi.org/10.1086/225469

- Grootaert, C., & Van Bastelaer, T. (2001). Understanding and measuring social capital: A synthesis of findings and recommendations from the social capital initiative.

- Guriev, S., & Melnikov, N. (2018). Happiness convergence in transition countries. Journal of Comparative Economics, 46(3), 683–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2018.07.003

- Guriev, S., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2009). (Un)happiness in transition. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(2), 143–168. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.23.2.143

- Helliwell, J. F. (2006). Well-being, social capital and public policy: What's new?. The Economic Journal, 116(510), C34–C45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01074.x

- Helliwell, J. F., & Huang, H. (2008). How's your government? International evidence linking good government and well-being. British Journal of Political Science, 38(4), 595–619. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000306

- Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2014). Social capital and well-being in times of crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(1), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9441-z

- Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2018). In E. M. Uslaner (Ed.), New evidence on trust and well-being. Oxford Handbooks Online.

- Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1435–1446. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1522

- Helliwell, J. F., & Wang, S. (2011). Trust and wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 1(1), 42–78. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v1i1.22

- Hudson, J. (2006). Institutional trust and subjective well-being across the EU. Kyklos, 59(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2006.00319.x

- Huggins, R., & Thompson, P. (2015). Local entrepreneurial resilience and culture: The role of social values in fostering economic recovery. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 8(2), 313–330. J Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsu035

- Inaba, Y., Wada, Y., Ichida, Y., & Nishikawa, M. (2015). Which part of community social capital is related to life satisfaction and self-rated health? A multilevel analysis based on a nationwide mail survey in Japan. Social Science & Medicine, 142, 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.007

- Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic and political change in 41 societies. Princeton University Press.

- Inglehart, R. F., Borinskaya, S., Cotter, A., Harro, J., Inglehart, R., Ponarin, E., & Welzel, C. (2013). Genes, security, tolerance and happiness. Higher School of Economics Research Paper No. WP BRP 31/SOC/2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2373161

- Inglehart, R., Foa, R., Peterson, C., & Welzel, C. (2008). Development, freedom, and rising happiness: A global perspective (1981–2007). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(4), 264–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00078.x

- Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. Random House.

- Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533006776526030

- Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291575

- Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251–1288. Retrieved from https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:oup:qjecon:v:112:y:1997:i:4:p:1251-1288. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300555475

- Kroll, C. (2011). Different things make different people happy: Examining social capital and subjective well-being by gender and parental status. Social Indicators Research, 104(1), 157–177. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41476546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9733-1

- Kuroki, M. (2011). Does social trust increase individual happiness in Japan? Japanese Economic Review, 62(4), 444–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5876.2011.00533.x

- Laursen, K., & Foss, N. (2003). New human resource management practices, complementarities and the impact on innovation performance. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 27(2), 243–263. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23601801

- Lenzi, C., & Perucca, G. (2016). Life satisfaction across cities: Evidence from Romania. The Journal of Development Studies, 52(7), 1062–1077. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2015.1113265

- Licata, L., & Klein, O. (2002). Does European citizenship breed xenophobia? European identification as a predictor of intolerance towards immigrants. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 12(5), 323–337. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.684

- Mellander, C., Florida, R., & Rentfrow, J. (2012). The creative class, post-industrialism and the happiness of nations. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 5(1), 31–43. J Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsr006

- Mendoza-Botelho, M. (2013). Social capital and institutional trust: Evidence from Bolivia's popular participation decentralisation reforms. Journal of Development Studies, 49(9), 1219–1237. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2013.786961

- Mikucka, M., Sarracino, F., & Dubrow, J. K. (2017). When does economic growth improve life satisfaction? Multilevel analysis of the roles of social trust and income inequality in 46 countries, 1981–2012. World Development, 93, 447–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.01.002

- Mooi, E., Sarstedt, M., & Mooi-Reci, I. (2018). Principal component and factor analysis. In Market research: The process, data, and methods using stata (pp. 265–311). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5218-7

- Nikolova, E., & Sanfey, P. (2016). How much should we trust life satisfaction data? Evidence from the life in transition survey. Journal of Comparative Economics, 44(3), 720–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2015.11.003

- Nikolova, M. (2016). Minding the happiness gap: Political institutions and perceived quality of life in transition. European Journal of Political Economy, 45(Suppl), 129–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2016.07.008

- Nooteboom, B. (2007). Social capital, institutions and trust. Review of Social Economy, 65(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346760601132154

- Obrizan, M. (2020). Transition welfare gaps: One closed, another to follow? Economics of Transition and Institutional Change, 28(4), 621–635. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecot.12252

- OECD. (2011). Society at a glance 2011: OECD social indicators. OECD Publishing Paris.

- OECD. (2013). OECD guidelines on measuring subjective well-being. OECD Publishing Paris.

- Ottaviano, G., & Peri, G. (2005). Cities and cultures. Journal of Urban Economics, 58(2), 304–337. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:juecon:v:58:y:2005:i:2:p:304-337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2005.06.004

- Paldam, M. (2000). Social capital: One or many? Definition and measurement. Journal of Economic Surveys, 14(5), 629–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6419.00127

- Pargal, S., Huq, M., & Gilligan, D. (1999). Social capital in solid waste management. Evidence form Dhaka Bangladesh. The World Bank.

- PEW. (2018). Eastern and Western Europeans differ on importance of religion, views of minorities, and Key social issues. PEW Research Center. Retrieved from: https://www.pewforum.org/2018/10/29/eastern-and-western-europeans-differ-on-importance-of-religion-views-of-minorities-and-key-social-issues/

- Portela, M., Neira, I., & del Mar Salinas-Jiménez, M. (2013). Social capital and subjective wellbeing in Europe: A new approach on social capital. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 493–511. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24720260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0158-x

- Portes, A. (1998). Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

- Poutvaara, P., & Steinhardt, M. F. (2018). Bitterness in life and attitudes towards immigration. European Journal of Political Economy, 55, 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2018.04.007

- Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1995.0002

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: the collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster.

- Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., & Nanetti, R. Y. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic tradition in modern Italy. Princton University Press.

- Rampichini, C., & Schifini d'Andrea, S. (1998). A hierarchical ordinal probit model for the analysis of life satisfaction in Italy. Social Indicators Research, 44(1), 41–69. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006888613727

- Reid, C., & Salmen, L. (2000). Understanding social capital. Agricultural extension in Mali: Trust and social cohesion. The World Bank.

- Requena, F. (1995). Friendship and subjective well-being in Spain: A cross-national comparison with the United States. Social Indicators Research, 35(3), 271–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01079161

- Roaf, J., Atoyan, R., Joshi, B., & Krogulski, K. (2014). 25 years of transition. Post-communist Europe and the IMF. International Monetary Fund.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Maslauskaite, K. (2012). Can policy make us happier? Individual characteristics, socio-economic factors and life satisfaction in Central and Eastern Europe. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 5(1), 77–96. J Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsr038

- Sabatini, F. (2008). Social capital and the quality of economic development. Kyklos, 61(3), 466–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2008.00413.x

- Sanfey, P., & Teksoz, U. (2007). Does transition make you happy? The Economics of Transition, 15(4), 707–731. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0351.2007.00309.x

- Saukani, N., & Ismail, N. A. (2019). Identifying the components of social capital by categorical principal component analysis (CATPCA). Social Indicators Research, 141(2), 631–655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1842-2

- Sequeira, T. N., & Ferreira-Lopes, A. (2011). An endogenous growth model with human and social capital interactions. Review of Social Economy, 69(4), 465–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2011.592330

- Serageldin, I., & Bank, W. (1996). Sustainability and the wealth of nations: First steps in an ongoing journey. World Bank.

- Setterfield, M. (2020). Managing the discontent of the losers. Review of Social Economy, 78(1), 77–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346764.2019.1623908

- Steptoe, A., Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2015). Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. The Lancet, 385(9968), 640–648. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61489-0

- Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. (2009). Report of the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress (CMEPSP). Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (France).

- Switek, M. (2012). Life satisfaction in Latin America: A size-of-place analysis. The Journal of Development Studies, 48(7), 983–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2012.658374

- Uphoff, N. (1999). Understanding social capital: Learning from the analysis and experience of participation. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank.

- Uslaner, E. M. (1999). Democracy and social capital. Cambridge University Press.

- van der Horst, M., & Coffé, H. (2012). How friendship network characteristics influence subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 107(3), 509–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9861-2

- Veenhoven, R. (2015). Social conditions for human happiness: A review of research. International Journal of Psychology, 50(5), 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12161

- WHO. (2012). Measurement of and target-setting for wellbeing: An initiative by the WHO regional office for Europe. WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Wilson, H. F. (2016). ‘Brexit: On the rise of ‘(in)tolerance’. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.32932.27521

- Yip, W., Subramanian, S. V., Mitchell, A. D., Lee, D. T., Wang, J., & Kawachi, I. (2007). Does social capital enhance health and well-being? Evidence from rural China. Social Science & Medicine, 64(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.027