Professor Brian Robert Allanson, the doyen of South African zoology professors, died in Cape Town on 10 July 2022 at the age of 94 years. He is survived by his wife, Sue, five children, 12 grandchildren and three great grandchildren. Brian was born in Colombo, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) on New Year’s Day in 1928 where his father, Arthur, was a marine engineer. The Allanson family moved to the United Kingdom when Brian was an infant and then to Port Elizabeth in 1938. Brian’s passionate interest in biology manifested early in life as he enjoyed dissecting rabbits, rats and all manner of other creatures.

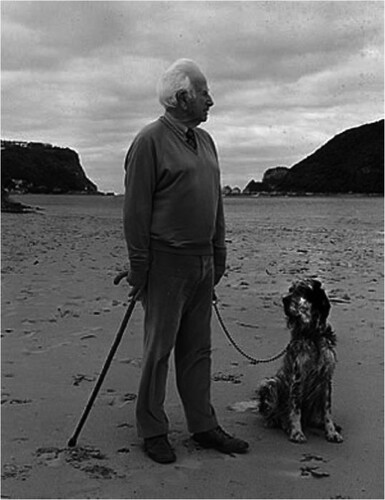

Figure 1. Professor Allanson on the beach staring out over his beloved Knysna Lagoon. Photo: Knysna Basin project.

He was schooled at Grey High School and studied zoology and chemistry at the University of Natal in Pietermaritzburg, graduating in 1948. Whilst a student at the University of Natal in 1948 Brian took part in a research expedition organised by Dr George Campbell to Maputaland (including Lake Sibaya, an unexplored lake at the time). This trip whetted his appetite for doing research in the area, which eventually came to fruition 20 years later. This episode emphasises the importance of early student involvement in field research. After three years as Assistant Science Master at Hilton College, he earned his master’s degree in marine biology at the University of Cape Town (UCT) and taught there as a junior lecturer in zoology for a year while commencing his studies for a PhD. In 1955 he joined the Zoology Department at UCT as a junior lecturer under Professor John Day. Later that year he married Sue Nicholson, who was studying librarianship at the university.

When Brian received a four-year research fellowship from the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) and the Transvaal Provincial Administration, he and Sue moved to Pretoria where he was tasked with monitoring the health of the rivers that supply water to the province. During this period he was sent to England for a year as a visiting researcher at the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR) Water Pollution Laboratories in Stevenage, Hertfordshire, where he completed the write-up for his PhD from UCT. On his return he was appointed Head of the Division of Hydrobiology at the CSIR’s National Institute for Water Research, where he continued his work on rivers and reservoirs.

In 1963, at the age of only 35 years, Brian Allanson was appointed Professor of Zoology and Entomology at Rhodes University, a position he held with distinction for the next 25 years. The dashing young professor apparently caused quite a stir in the quiet “City of Saints” and became the university’s first Dean of Research and one of the scholarly giants on the campus. His advice to struggling students was always, “Be strong and of good courage” (Joshua, 1, v 9), or “Go sit quietly and think.” It is no accident that the Department of Zoology and Entomology remains one of the top-performing research departments on the Rhodes University campus.

In 1965 Professor Allanson established the Institute for Fresh Water Studies (IFWS) at Rhodes University and became its first Director. In 1968 he established a research station on the shores of South Africa’s largest natural freshwater lake, Lake Sibaya, which became an active hub for research in Maputaland, a poorly studied part of northern Zululand. The Lake Sibaya research programme was funded by the International Biological Programme (IBP) and attracted wide participation. At its peak the research station hosted scientists from Rhodes University as well as from 31 other institutions in South Africa and abroad. As a result, the coastal lakes and estuaries of Maputaland were intensively studied and documented and numerous recommendations for the conservation, management and sustainable utilisation of its natural resources were submitted to the local and regional authorities.

Brian Allanson later established field research stations in Port Alfred, on the Wilderness lakes at Sedgefield and in Knysna, all of which had a positive impact on research, conservation and management in their regions. Under his leadership the IFWS played a pivotal role in harnessing the contributions of many universities and research institutions to produce knowledge and understanding on the physiology, chemistry and biology of coastal lakes and estuaries throughout southern Africa. The IFWS later merged with the Hydrological Research Unit to form the Institute for Water Research at Rhodes University.

My first brush with Professor Allanson was during my first year as a zoology student, in 1966, when I experienced the authoritarian side of his character. I arrived at a Zoology 1 practical in a Rolling Stones t-shirt and, without uttering a word, he pointedly gestured to the door, making it quite clear that I should go back to my room and get dressed properly! My first face-to-face encounter with him was at the beginning of my second year in 1967 when he asked me a single, blunt question: “Did you pass Chemistry 1?” (most Zoology I students didn’t). I replied in the affirmative and, from that day onwards, we built up a friendship – from teacher to mentor, employer and colleague – that lasted for 56 years. In April 2012, at an honorary graduand’s lunch at Rhodes University, I mentioned that my lifelong friendship with Professor Allanson epitomised the collegiate spirit of this small but close-knit university, whose motto is “Where leaders learn.” It did, however, take me about 30 years before I plucked up the courage to call the formidable professor “Brian.” He addressed me as “Dear fellow.”

We went on expeditions to remote parts of southern Africa together and flew from Grahamstown (Makhanda) to the Orange River and back in his Piper Cherokee 180 (call sign “Echo Oscar Delta”) that he piloted himself with great skill. We scuba dived together in the crocodile-infested waters of Lake Sibaya and enjoyed many a fireside chat about things zoological. Brian was not a natural scuba diver. I remember him once tossing an article entitled “Man is not a sea-going animal” (on which he had scrawled “Divers, please note”) onto the library table in the old Zoology Department during teatime. I was with him on his last scuba dive in Lake Sibaya. He was clearly uncomfortable and, when we surfaced, he said, “That’s it, no more underwater work for me.” But he did appreciate the value of looking a fish in the eye in its natural habitat when one is trying to understand its life history, and encouraged further diving.

While he was employed full-time at Rhodes University, Brian suffered what can only be called a “midlife crisis” when he bought two farms and became a gentleman farmer. Although he learned agricultural skills from the somewhat-bewildered local Salem farmers, in truth Sue did most of the farming and this episode did not last long. Brian was also heavily involved in charity work and was a long-serving member of the Rotary Clubs in Grahamstown and Knysna.

During his time at Rhodes University Professor Allanson enjoyed spells at Indiana University, Oxford University and the Ferry House, Windermere, as a visiting professor and researcher, and collaborated with the water research centre at the University of Western Australia. In 1983 he established the Southern Ocean Research Group with projects on Marion Island and in Antarctica. There he developed a multi-disciplinary approach to the study of complex ecosystems, and his programme was one of the first to advance our understanding of global climate change. Amongst his research highlights at this time he served as Chief Scientist on two voyages of the South African Antarctic research vessel, SA Agulhas, to the Antarctic. In terms of research needs the Chief Scientist has authority over the captain, provided that his orders do not conflict with the safety of the ship and its crew. Brian typically got on well with Captain Leith and, when the ship reached the ice shelf and the arduous task of offloading began, the scientists were responsive to Brian’s “encouragement” to assist with the offloading, which was greatly appreciated by the captain and crew.

Despite his onerous administrative responsibilities, Professor Allanson was a prodigious publisher of scientific papers, reports and books and made seminal contributions (a favourite phrase of his) to physico-chemical limnology, freshwater ecology, oceanography, polar science, zoology and other fields. Most significantly, he opened doors of opportunity for generations of students and young researchers – this author included – that set them on their life paths. That is the most important contribution that a research leader can make. His ex-students now populate freshwater, marine and biological science programmes throughout the world. To honour his contributions, his students and colleagues at Rhodes University established the Professor B.R. Allanson Scholarship for post-doctoral study.

After his formal retirement in 1988, Professor Allanson continued to serve Rhodes University as a researcher and mentor of distinction. He and Sue, who faithfully supported him for 67 years throughout his long scientific career, moved to Leisure Isle in Knysna where he started a practice as a consulting aquatic ecologist. In 1995 he established the Knysna Basin Project, in collaboration with the Outeniqualand Trust, which continues to serve the local and international community to this day, safeguarding the health of one of our most important estuarine systems, with special emphasis on the plight of the endangered Knysna seahorse. At the age of 90 he published a journal article and graduated a PhD candidate, an extraordinary example of inspired and determined scholarship.

Brian Allanson was a devoted family man who called his extended family the “A Team” and often shared their accomplishments with others. He was a keen yachtsman who built and sailed two dinghies, an “Enterprise” and a “Mirror,” and sailed a yacht on Knysna Lagoon as well as on Lake Windermere and the Broads in Norfolk during sabbatical leaves. He was a brilliant orator, an avid devotee of classical music (especially Bach, Mozart and Beethoven) and a keen pianist. In Pretoria he and a friend, Henry Walsh (clarinet) played together, and, in Grahamstown, he was accompanied by fellow zoologists Bob van Hille on the cello and Robin Boltt on the clarinet.

Brian’s son, Peter Allanson, recalled at his memorial service that his grand piano was also a good mood indicator. If he had had a good day at the office in the Zoology Department he would caress the keys to the chords of Bach upon returning home, but Beethoven would get a good working over if he had had a bad day! At legendary student parties at his and Sue’s home, “The Little Hermitage,” he even deigned to accompany our raucous singing! After he retired to Knysna, Brian played the organ in the Anglican Church on Sundays until his increasing deafness made it impossible for him to do so.

In addition to being an accomplished scientist Brian Allanson was a knowledgeable naturalist who enjoyed sharing his knowledge of wildlife with family and friends. At his memorial service one of his granddaughters, Rosanne, remembered a hike they had gone on together through marshlands in Knysna, during which “He spoke through the bird species that we saw. Little did I know that there would be a quiz afterwards!” He was an avid gardener who delighted in presenting bouquets of homegrown flowers to guests. Brian also had a wicked sense of humour, with a particular fondness for the Goon Show and Mr Bean. He was a great lover of dogs and would go on long rambles with them around Knysna Lagoon (), wearing a tartan tie and worn corduroys, his shock of white hair blowing in the wind. He always wielded an authoritative walking stick which he waved around while discussing ecological phenomena or conservation issues with whomever he encountered.

Professor Allanson received many honours and awards including the Fellowship of the Royal Society of South Africa, the Gold Medal of the Zoological Society of Southern Africa, South Africa’s Order for Meritorious Service – Silver, the Sanlam Lifetime Achievement Award, Doctor of Science Honoris causa, Distinguished Research Fellow from Rhodes University, and the Naumann-Thienemann Medal, the highest honour bestowed internationally for scientific contributions to limnology. In 2016 he jointly won the Rhodes University Environmental Award with one of his postgraduate students, Dr Louw Claassens, who took over the Knysna Basin Project from him; this project is now managed by Emeritus Professor Charles Breen.

One of my favourite photographs of Brian, taken by my wife, Carolynn, shows him in his bright red shorts collecting neuston along the shores of Lake Sibaya with a hand net. We called the photo, “The Great White Shark filter feeding” (although great whites are not filter feeders). Towards the end of his life, when we visited Brian and Sue in their retirement home in Noordhoek, he had lost his hearing and we communicated by writing notes to one another, but he nevertheless retained a keen interest in everything we were doing.

Brian Allanson was a larger-than-life character, the professor’s professor, but behind the haughty exterior lay a great intellect, a gifted researcher and administrator, and a very personable human being who was renowned for his integrity and generosity. He was a towering intellect and a father figure for many, whose legacy will live on for generations.