With global incidence of 34 per 100,000 [Citation1,Citation2], acute pancreatitis is one of the most frequent gastrointestinal diseases but clinical research on gastrointestinal motility in its setting remained, until very recently, nescient. While gastrointestinal barrier function in acute pancreatitis has been investigated in dozens of prospective clinical studies since 1980s [Citation3], very little is known about changes in gastrointestinal motility associated with this disease. Striking knowledge gap for the twenty-first century medical science! At least in part, this is because traditional (e.g., manometry, scintigraphy) and emerging (e.g., high-resolution electrical mapping of the gastrointestinal tract, computational modelling of gastrointestinal fluid dynamics) instrumental techniques employed in gastrointestinal motility research are impractical to use in the setting of clinical acute pancreatitis.

The past two years have seen the nascence of clinical motility research in acute pancreatitis, triggered by validation of a simple, non-invasive and inexpensive instrument assessing patient-reported symptoms, called the Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (GCSI) daily diary, in a randomized controlled trial of enteral feeding versus nil-per-os [Citation4]. The study revealed a high prevalence of dysmotility-related symptoms in patients with acute pancreatitis. Moreover, the GCSI responded well to clinical change, as evidenced by strong total score reduction over the study period in the entire cohort and by significantly better appetite in those patients who received enteral feeding. A subsequent pilot clinical study by COSMOS group found that the GCSI can be used as an early predictor of feeding intolerance as well as non-mild course of acute pancreatitis [Citation5]. This was followed by a prospective cohort study of 217 patients with acute pancreatitis (also conducted by COSMOS group), which confirmed clinical usefulness of the GCSI in prediction of feeding intolerance [Citation6]. Specifically, it showed that the risk of feeding intolerance was raised by 45% for every one point increase in GCSI on day 2 of admission, even after adjustment for covariates such as age, sex, aetiology of acute pancreatitis, severity of acute pancreatitis, time from symptom onset, and diabetes status. Furthermore, a nomogram was devised to determine the predicted probability of feeding intolerance during hospitalization [Citation6].

The study by Hongyin et al. [Citation7] in April issue of the Journal is a welcome addition to the nascent literature on gastrointestinal motility in acute pancreatitis. The authors used the GCSI to study changes in tolerance of enteral feeding in 161 patients with acute pancreatitis. The study showed that a third of participants (n = 53) developed feeding intolerance, confirming that it is the most common complication in modern-day patients with acute pancreatitis irrespective of disease severity [Citation8–10]. Also, it is reassuring that the GCSI was able to detect gastrointestinal symptom reductions over seven days, thus demonstrating its responsiveness to various clinical changes in different clinical settings.

Unfortunately, several aspects of the study by Hongyin et al. suggest that it is a methodologically nescient study. First, neither power calculation nor description of dropouts and withdrawals was reported. And the phrase ‘the allocation ratio of trial participants is about 1:1 within the blocks’ indicates misunderstanding of the concept of block randomization, let alone substandard English writing skills. Second, feeding protocol was not standardised, in particular in relation to the key questions informing the nutritional management of acute pancreatitis: what to feed, when to feed and who governs these feeding decisions [Citation11]. Third, iatrogenic factors such as opiate analgesics and liberal fluids may lead to (or exacerbate) gut dysmotility [Citation12] but the authors provided a woeful description of pain management and fluid resuscitation in study participants. Furthermore, the opportunity to investigate the effect of opiate analgesics and liberal fluids on the GCSI has been overlooked. Last, the amount of ascites was not quantified and the dynamics of its accumulation was not specified. These are important because a limited amount of peritoneal ascitic fluid during the early course of first episode of acute pancreatitis usually represents just a reactive phenomenon: leaky capillaries induced by the inflammatory process in the pancreas and the body’s defence mechanism to dilute and flush away proinflammatory cytokines as well as other inflammatory mediators. Fluid that arises from disrupted duct syndrome or rupture of pseudocyst is the other theoretically possible cause of ascites but it is very uncommon to observe it in the early course of first episode of acute pancreatitis.

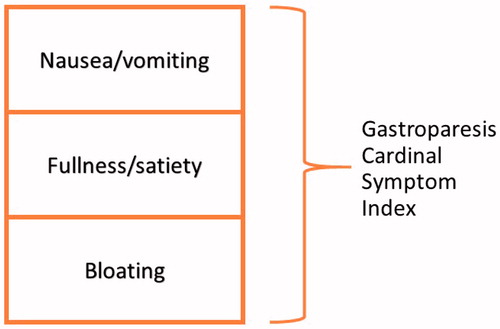

Whether or not to use classical peritoneal drainage in patients with acute pancreatitis is a dead issue [Citation13] and none of practice guidelines in the Western world makes a positive recommendation for its use. However, the study by Hongyin et al. should not be marginalized. It clearly showed that the GCSI can be used as an outcome measure in acute pancreatitis research. While the GCSI was originally developed as a symptom-based endpoint for clinical trials in chronically-ill gastroparesis patients, the emerging literature demonstrates that specific symptoms registered () are highly compatible with those experienced by acute pancreatitis patients with dysmotility. This is not unexpected because the gastrointestinal symptoms are limited and similar in character, whether in acute or chronic states of dysmotility. Further, given that two out five patients with acute pancreatitis develop new onset diabetes after pancreatitis (NODAP) and taking into account that three out five cases of diabetes associated with diseases of the exocrine pancreas develop after acute pancreatitis [Citation14], there is a potential to use the GCSI in ‘chronic-on-acute’ state of dysmotility – namely in clinical studies on NODAP. This may help to unearth intricate signalling pathways in this disease, involving the pancreas, the gastrointestinal tract and the brain [Citation15].

The GCSI is now an established standardised dysmotility endpoint with evidence supporting reliability and responsiveness suitable for use in clinical pancreatology. The first studies using the GCSI have contributed to the nascence of gastrointestinal motility research in acute pancreatitis and opened up new challenging opportunities to understand diseases of the exocrine and endocrine pancreas better. It will be worth it in the end.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Petrov is Principal Investigator of the COSMOS (Clinical and epidemiOlogical inveStigations in Metabolism, nutritiOn, and pancreatic diseaseS) group.

Disclosure statement

The author has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Xiao AY, Tan ML, Wu LM, et al. Global incidence and mortality of pancreatic diseases: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of population-based cohort studies. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:45–55.

- Sankaran SJ, Xiao AY, Wu LM, et al. Frequency of progression from acute to chronic pancreatitis and risk factors: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1490–1500.

- Wu LM, Sankaran SJ, Plank LD, et al. Meta-analysis of gut barrier dysfunction in patients with acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2014;100:1644–1656.

- Ma J, Pendharkar SA, O’Grady G, et al. Effect of nasogastric tube feeding vs nil per os on dysmotility in acute pancreatitis: results of a randomized controlled trial. Nutr Clin Pract. 2016;31:99–104.

- Wu LM, Premkumar R, Phillips AR, et al. Ghrelin and gastroparesis as early predictors of clinical outcomes in acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2016;16:181–188.

- Bevan MG, Asrani VM, Pendharkar SA, et al. Nomogram for predicting oral feeding intolerance in patients with acute pancreatitis. Nutrition. 2017;36:41–45

- Hongyin L, Zhu H, Tao W, et al. Abdominal paracentesis drainage improves tolerance of enteral nutrition in acute pancreatitis: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:389–395.

- Bevan MG, Asrani VM, Bharmal S, et al. Incidence and predictors of oral feeding intolerance in acute pancreatitis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Clin Nutr. 2016 [Epub ahead of print].

- Pendharkar SA, Asrani VM, Das SL, et al. Association between oral feeding intolerance and quality of life in acute pancreatitis: a prospective cohort study. Nutrition. 2015;31:1379–1384.

- Yang CJ, Chen J, Phillips AR, et al. Predictors of severe and critical acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:446–451.

- Bevan MG, Asrani VM, Petrov MS. The oral refeeding trilemma of acute pancreatitis: what, when and who? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:1305–1312.

- Petrov MS. Gastric feeding and “gut rousing” in acute pancreatitis. Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;29:287–290.

- Dong Z, Petrov MS, Xu J, et al. Peritoneal lavage for severe acute pancreatitis: a systematic review of randomised trials. World J Surg. 2010;34:2103–2108.

- Pendharkar SA, Mathew J, Petrov MS. Age- and sex-specific prevalence of diabetes associated with diseases of the exocrine pancreas: a population-based study. Dig Liver Dis. 2016 [Epub ahead of print].

- Pendharkar SA, Asrani VM, Murphy R, et al. The role of gut-brain axis in regulating glucose metabolism after acute pancreatitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017;8:e210.