Abstract

Aim: To investigate inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) register-based subtype classifications over a patient’s disease course and over time.

Methods: We examined International Classification of Diseases coding in patients with ≥2 IBD diagnostic listings in the National Patient Register 2002–2014 (n = 44,302).

Results: 18% of the patients changed diagnosis (17% of adults, 29% of children) during a median follow-up of 3.8 years. Of visits with diagnoses of Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC), 97% were followed by the same diagnosis, whereas 67% of visits with diagnosis IBD-unclassified (IBD-U) were followed by another IBD-U diagnosis. Patients with any diagnostic change changed mostly once (47%) or twice (31%), 39% from UC to CD, 33% from CD to UC and 30% to or from IBD-U. Using a classification algorithm based on the first two diagnoses (‘incident classification’), suited for prospective cohort studies, the proportion adult patients with CD, UC, and IBD-U 2002–2014 were 29%, 62%, and 10% (43%, 45%, and 12% in children). A classification model incorporating additional information from surgeries and giving weight to the last 5 years of visits (‘prevalent classification’), suited for description of a study population at end of follow-up, classified 31% of adult cases as CD, 58% as UC and 11% as IBD-U (44%, 38%, and 18% in children).

Conclusions: IBD subtype changed in 18% during follow-up. The proportion with CD increased and UC decreased from definition at start to end of follow-up. IBD-U was more common in children.

Introduction

Guidelines underline the importance of a complete diagnostic workup to classify patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) into Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC) in order for patients to receive the best management [Citation1–5]. However, in some patients with colonic disease, the diagnosis of CD or UC cannot be clearly ascertained. For such cases, it is recommended to use the term IBD unclassified (IBD-U) [Citation1]. The term indeterminate colitis is restricted to cases without a definitive diagnosis after complete histologic analysis of surgical specimens [Citation1,Citation4,Citation5].

The frequency of IBD-U is usually reported to be higher among pediatric patients compared to that of the adult population: 13 versus 6% in a meta-analysis [Citation6], and to be decreasing over disease course [Citation7]. In well characterized IBD cohorts, the proportion of IBD-U has been reported to range from 1 to 20% in adults [Citation8–20] and from 4 to 22% in pediatric patients [Citation21–33]) ().

Table 1. Proportion inflammatory bowel disease unclassified (IBD-U) in well-characterized cohorts with at least 400 participants.

In register-based studies, the proportion of CD, UC and IBD-U varies according to the definition of IBD subtypes [Citation34–41] (). Some researchers have chosen only to report CD and UC [Citation42–45]. Some classification schemes have been based on the first diagnosis code assigned [Citation43,Citation44], while others have been based on the most frequent coding [Citation34,Citation38,Citation39]. In epidemiologic studies, use of longitudinal follow up data to retrospectively classify incident cases may introduce bias. Therefore, in prospective cohort studies of the association between IBD subtype and future outcomes, the definition should be based on available data at start of follow-up. However, there is also a need for a classification of a study population during, or at end of, follow-up, based on all available information. Different IBD diagnoses might be documented during a patient’s medical history; either due to a colitis that is hard to distinguish between UC or CD, or simply because of occasional incorrect coding in the records [Citation46]. We therefore sought to examine changes in IBD diagnoses over time in the Swedish Patient Register and to demonstrate how alternative definitions based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes affect the proportions of CD, UC and IBD-U.

Table 2. Register-based definition and proportion of inflammatory bowel disease unclassified (IBD-U) in different studies.

Methods

Setting

The Swedish health care system is tax funded and offers universal access. Prescription drugs are provided free of charge above a threshold of 2200 SEK annually (approximately 200€). Patients with IBD are typically diagnosed and treated by gastroenterologists in hospital-based outpatient facilities.

Data sources

The National Patient Register holds dates on hospital admissions since 1964, with national coverage since 1987. From 1997 and onward surgical day care procedures, and since 2001, nonprimary outpatient physician visits have been reported to the register. Visits to general practitioners (i.e., primary care in Sweden) are not included. Main and contributory diagnoses are coded according to the International Classification of Disease (Tenth Revision since 1997, ICD-10) codes and assigned by the treating physician [Citation47]. Surgical procedures are coded according to an adapted version of the NOMESCO Classification of Surgical Procedures [Citation48,Citation49]. The Total Population Register records dates of emigration and death of all residents in Sweden and is continuously updated [Citation50]. Linkage was possible through the unique personal identity number, issued to all Swedish residents [Citation51].

Identification of patients

We identified a cohort of individuals based on IBD-related ICD codes from the Swedish National Patient Register from 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2014. The definition of IBD (list of ICD codes used in Supplementary Table S1) required two or more inpatient or nonprimary outpatient care visits for either CD, UC or K52.3 (IBD-U) [Citation40,Citation41,Citation52], which has a positive predictive value (PPV) of 93% (95% confidence interval, CI, 87–97) [Citation46]. Follow-up started on the date of the first IBD diagnosis, and ended on the date of death, emigration from Sweden, or 31 December 2014, whichever came first. We restricted our analyses to patients with IBD onset on or after 1 January 2002, to allow for at least one year of wash out, during which prevalent IBD cases were captured by the outpatient register (Supplementary Figure S1).

Codes specific for Crohn’s disease

Some ICD-codes are considered typical for CD, e.g., perianal disease and small bowel disease, and some surgeries are consequently performed in CD patients and not UC patients, e.g., perianal surgery and small bowel surgery. Earlier studies have shown that a large proportion of patients with CD later undergo surgery [Citation53]. We investigated the occurrence of such ICD and surgical procedure codes in patients with CD, UC, and K523 (Supplementary Table S2).

Statistics

We compared the ICD codes at initial diagnosis in relation to the diagnosis codes assigned at the follow up visits, and we determined the frequency and timing of each type of change in IBD subtype, as well as the number of changes per patient. We determined the number and percentage of visits where the diagnosis was the same as the starting diagnosis (the patient may have had different ICD-codes on the first two visits but both should represent CD, UC, or K52.3, respectively). We calculated the mean percentage of follow-up time, and the mean percentage of number of visits, at which the patient had the same diagnosis during the subsequent visit as at initial diagnosis. We also determined the longest sequence of visits where the diagnosis was the same as the initial diagnosis. We calculated the proportion of patients with ICD codes typical of CD according to Supplementary Table S2. We then developed a classification model based on all information available at end of follow-up, and calculated the proportions of CD, UC and IBD-U at different time points during the follow-up. R (version 3.3.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for statistical calculations.

Ethical approval

This project was approved by the Stockholm Ethics Review Board (2007/785-31/5; 2011/1509-32; 2014/1288-31/4; 2015/0004-31; 2015/615-32).

Results

Between 2002 and 2014, 4663 children (<18 years) and 39,639 adults had ≥2 IBD diagnoses in the Patient Register. Median time between first and last ICD code for IBD was 3.9 (min-max: 0–13) years.

Changes in IBD subtype during follow-up: descriptive analyses of type, timing and frequency

Patients with index date after 1 January 2002 (n = 44,302) had in total 484,049 in- or outpatient visits with an IBD diagnosis, and 7930 (18%) of patients changed subtype diagnosis coding at some point during follow up (17% of adult-onset and 29% of childhood-onset IBD patients). There were 407 (0.08%) visits with multiple diagnoses on the same date (referred to as ‘mixed’ diagnosis).

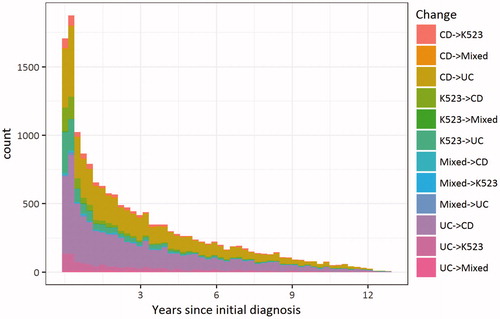

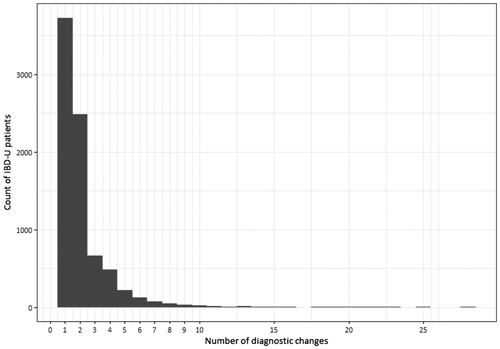

Out of all visits where the diagnosis assigned was different from the previous one, 39% of changes were from UC to CD, 33% from CD to UC, and all other changes were to or from K52.3/mixed diagnoses (). Among the patients who had a change in subtype diagnosis coding, 47% changed diagnosis only once, 31% changed diagnosis twice. Some had 3 (8%), 4 (6%), 5 (3%), or 6 (2%) changes, and a few patients (less than 1%) had more changes, up to a maximum of 28 changes ().

Figure 1. Frequency and timing of each type of change in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) subtype since first IBD diagnosis in patients with incident IBD 2002–2014 who changed diagnosis at some point during follow-up (n = 7930 out of 44,302). A patient can contribute several types of diagnostic changes and the same type of diagnostic change several times.

Figure 2. Number of changes in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) subtypes in patients with incident IBD 2002–2014, who changed diagnosis at some point during follow-up (n = 7930 out of 44,302).

For patients who had a diagnostic change at some stage or any diagnosis of K52.3 (in total n = 8618), diagnoses of CD and UC were fairly stable from one visit to the next, while K52.3 or mixed diagnoses changed more frequently (Supplementary Table S3, Supplementary Table S4). Among all patients, 97% of visits with CD diagnosis were followed by another visit with CD diagnosis, and the same was true for UC. For K52.3, 67% of visits with an initial diagnosis of K52.3 were followed by K52.3.

Occurrence of ICD-codes specific for CD

Occurrence of ICD codes considered specific for CD (perianal and small bowel disease and surgery) was first investigated in patients who never changed diagnosis. In patients with only diagnostic listings of UC during follow-up around 2% had small bowel resection, 4.3% of adults and 4.6% of children had perianal surgery, and in total 6.6% of adults and 6.1% of children had any code considered typical of CD according to Supplementary Table S2. In contrast, 28% of adults and 22% of children with only diagnostic listings of CD during follow-up had small bowel resection, 13% of adults and 17% of children had perianal surgery, and 60% of adults and 59% of children had at least one of the codes considered typical of CD. Among patients with only K52.3 listings during the study period, 11% of adults and 10% of children had small bowel resection at some time point, 13% of adults and 16% of children had perianal surgery, and 34% of adults and 36% of children had at least one code typical of CD (Supplementary Table S5).

Rationale for the ‘prevalent’ classification

The majority of visits (67%) with a diagnosis of K52.3 were diagnosed as K52.3 the next visit. Among patients with a change of IBD subtype, most changed only once or twice, and the most common change was from UC to CD and occurred during the first 5 years of follow-up. ICD-codes considered typical of CD occurred frequently (60%) in patients with only listings of CD, rarely in patients with only listings of UC (7%), and in 34% of patients with only listings of K52.3.

Based on these findings, we developed a ‘prevalent’ classification, defined at end of follow-up. The steps were:

Patients with only listings of CD were classified as CD and patients with only UC were classified as UC.

Patients with any listing of K52.3 were classified as IBD-U.

Patients who had a diagnostic shift between UC and CD (or vice versa), but only one of the diagnoses during the past 5 years were classified according to the diagnosis that occurred during the last 5 years of follow-up (the 5 years preceding last IBD diagnosis).

Patients with both CD and UC diagnoses during the past 5 years of follow-up were classified as CD if they had any of the ICD-codes typical of CD listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Patients with both UC and CD diagnoses during the past 5 years of follow-up, who did not have any of the ICD-codes typical of CD, were classified as IBD-U.

When applying the different steps of the definition we observed the following:

Patients with only diagnosis of CD or UC remained CD (n = 11,974, 27%) or UC (n = 23,669, 53%).

Patients with any diagnosis of K52.3 were classified as IBD-U (n = 2317, 5%).

Patients who had a mix of UC and CD and no diagnosis of K52.3 (n = 6312, 14%) were classified according to the diagnosis that occurred during the last 5 years of available follow-up, which classified 965 (2%) as CD, and 887 (2%) as UC.

The remaining 4460 (10%) of patients with changes between UC and CD, and who had both diagnoses in the past 5 years, were then classified as CD if they had any of the ICD codes related to CD. This step classified another 1227 (3%) patients as CD.

The 3233 (7%) patients with both UC and CD diagnoses in the past 5 years and no ICD-codes typical of CD were classified as IBD-U.

Impact of different definitions on the proportion of IBD subtypes

We then calculated the proportion of patients with CD, UC and IBD-U, using definitions defined at start or at end of follow-up:

The classification based on only the first two diagnostic codes, ‘incident definition’ (IBD subtype at diagnosis).

The ‘prevalent’ definition (IBD subtype during follow-up), giving weight to the last 5 years of follow-up, and incorporating codes specific for CD.

‘Incident’ definition of IBD subtype

When the IBD subtype definition was based on the first two diagnostic listings alone, the proportion CD in adults was 29%, UC 62% and IBD-U 10%. In children, the proportion CD was 43%, UC 45%, and IBD-U 12% (Supplementary Table S6). When stratifying for year of onset, the proportion IBD-U increased over time, from 6% 2002–2005 to 11% in 2006–2014 in adults, and from 9% to 14% in children, comparing the same time periods.

‘Prevalent’ definition of IBD subtype

Using the ‘prevalent’ definition, 31% of the adult patients were classified as CD, 58% as UC and 11% as IBD-U, and in children the proportion CD was 44%, UC 38% and IBD-U 18% (Supplementary Table S7). The proportion IBD-U increased over time in both adults and children.

The proportion of CD in adult-onset IBD thus increased from 28% to 31% from definition at start of follow-up (‘incident definition’) to definition at end of follow-up (‘prevalent’ definition). The proportion adult-onset UC decreased from 62% to 58% from start to end of follow up, and the proportion IBD-U increased from 10 to 11%. In childhood-onset IBD the pattern was similar with an increase in CD from 43% to 44%, a decrease in UC from 45% to 38%, and an increase in IBD-U from 12% to 18%.

Sensitivity analyses

As a sensitivity analysis, we investigated the proportion of patients defined as CD, UC or IBD-U by the ‘prevalent’ definition of IBD subtype, defined at end of follow-up, but used different lengths of look back time (1, 2, 3, 10 and 15 years, as alternative to the 5 year look back) (Supplementary Table S8). We also investigated different lengths of follow-up stratified for year of onset (Supplementary Table S9). When increasing the length of time, on which the classification was based, the proportion adults classified as CD decreased slightly from 33% after 1 year of look back to 31% after 15 years of look back. The proportion adults with UC decreased from 60% using a 1 year look back period to 56% using 15 years look back, and the proportion IBD-U increased from 8% using 1 year look back to 13% using a 15-year look back. In childhood-onset IBD the proportion CD decreased from 47% to 43%, UC from 42% to 34%, and IBD-U increased from 12% to 23% when increasing the look back period from 1 to 15 years.

We also investigated a classification based on all diagnostic codes, where patients with a change between CD and UC diagnoses or K52.3 at any point were classified as IBD-U, ‘any mix classification’ (used in previous Swedish studies) [Citation40,Citation41]. When patients with any diagnostic shift, or occurrence of K 52.3 during follow-up, were classified as IBD-U, the proportion CD in adults was 26%, UC 56% and IBD-U 18%, and in children the proportion CD was 36%, UC 34%, and IBD-U 30% (Supplementary Table S10).

Discussion

In this study, we found that 18% of patients with IBD changed diagnosis at some point. Of visits with a diagnostic listing of CD or UC, 97% had the same diagnosis at the next visit, and 67% of visits with IBD-U-diagnosis were followed by another IBD-U diagnosis. Among those who changed ICD-coding, 37% changed from UC to CD, 33% from CD to UC, and 30% to or from IBD-U, and most patients changed only once or twice.

For the sub-classification of CD, UC, and IBD-U in register-based studies, we propose two algorithms. In prospective cohort studies, where we would be interested in examining the impact of IBD on the risk of some future event, we propose that the ‘incident’ register-based classification should be based solely on the 2 first diagnostic listings (since definition of exposure in any prospective analysis should of course not ‘look into the future’). We also propose a ‘prevalent’ definition for the classification of IBD subtype at end of follow-up, giving weight to diagnostic codes during the latest 5 years, while also incorporating codes specific for CD.

It is well known that some patients change IBD subtype over time. In a cohort of 739 closely followed IBD patients, Henriksen et al. [Citation12] found a change in diagnosis in 9% of CD and UC cases after 5 years of follow-up. In the latest follow-up of the EpiCom cohort of 488 patients diagnosed at Western and Eastern European centers in 2010, 18 patients with initial diagnosis of UC or IBD-U had their diagnoses changed to CD within 24 months, and 6 patients initially diagnosed with CD received a new diagnosis of UC, i.e., 5% changed diagnosis within 2 years [Citation54]. In our study the proportion of adult patients who changed diagnosis was similar: 59% were initially diagnosed as UC (using the ‘incident classification’) in 2006–2014, which decreased to 55% based on the latest 5 years of follow-up (‘prevalent definition). For CD the proportion was 29% based on initial diagnosis, and 31% based on the last 5 years of follow-up during the same time period.

When the subclassification in our study was based on all available follow-up time, the proportion of adult patients with only UC listings 2002–2014 was 56%, compared to 62% UC based on the first two diagnostic listings (i.e., 6/62 = 9.7% of patients initially diagnosed as UC had a diagnosis of CD or IBD-U at some point during follow-up). The proportion of patients with only CD listings was 26%, and 29% were determined as CD based on the first two diagnostic listings (i.e., 3/29 = 10% of patients initially diagnosed as CD had a subsequent diagnosis of UC or IBD-U). In children the proportion with only UC listings over the entire follow-up period was lower than in adults: 34% (45% based on the first two diagnostic listings) and 36% had only CD listings (43% based on the first two diagnostic listings).

In other studies, 23–84% of patients with an initial diagnosis of IBD-U were later classified as UC or CD [Citation9,Citation12,Citation24,Citation31–33,Citation55]. In pediatric patients, a systematic review found an increase in diagnosis of CD over time, and a decrease in IBD-U [Citation7]. In our material, the patients with listings of K52.3 most commonly had subsequent listings of K52.3. However, they changed diagnosis more frequently than patients with UC and CD, which is a reason to classify patients with any diagnosis of K52.3 as IBD-U.

In this study, IBD-U increased over calendar period irrespective of definition (start or end of follow-up). When investigating diagnoses in older cohorts, the most obvious explanation is the lack of ICD-code for IBD-U before 1997, however, the increase continued also after 1997. Other possible explanations include increasing register coverage and continuous improvements in routines around diagnostic coding, which increases the number of diagnoses, and thus the risk of having at least one discrepant diagnosis (e.g., to have one discrepant diagnosis out of four diagnoses is less likely than to have 1 discrepant diagnosis out of 20). The diagnosis of UC or CD is based on a combination of endoscopic and histological findings, radiology and clinical assessment. It has long been known that the drugs used in IBD can change the macroscopic appearance so that UC actually looks like CD [Citation56]. About 20% of patients with CD only have colitis [Citation57], and classic CD manifestations such as strictures and transmural inflammation are less common in the colon [Citation58]. The fact that the same patient may be registered with the ICD code for UC, CD and IBD-U reflects the difficulties seen in the clinic when deciding the most probable diagnosis, as noted also in previous studies ( and ). It is also possible that the disease panorama actually has changed, potentially due to a change in risk factors.

According to the definition of IBD-U used in previous Swedish register-based studies, all IBD-patients would be defined as IBD-U, if there had ever been, at any point in time during the patients’ history of IBD, any ambiguity regarding the most appropriate choice of diagnosis. The resulting proportion of IBD-U was consequently larger (16% in adults patients [Citation40]) than reported from other studies based on ICD-codes (∼4% [Citation37,Citation39]) or chart reviews (2 [Citation18,Citation20] to 4% [Citation13]). For pediatric patients, the prevalence of IBD-U in Sweden was reported to be 21% [Citation41], compared to a 10% proportion IBD-U in incident pediatric patients in Canada [Citation36] and only 2% in the relatively small but well characterized and long-term followed cohort from northern Stockholm [Citation59]. When defining all patients with diagnostic changes or K52.3 as IBD-U in our study, the proportion was 18% in adults and 30% in children during 2002–2014.

By our new ‘prevalent’ IBD subtype definition, the prevalence of pediatric IBD-U was 18%, which is still higher than in adults, and higher than reported in a large European cohort study at end of follow-up: 5.6% [Citation32]. The distinction between CD and UC can at times be more challenging in pediatric populations since colonic CD is a more common [Citation60]. In adults, UC is more common than CD, and cases of UC more often present as left-sided UC or proctitis.

Our choice to primarily classify patients who only had a mix of UC and CD according to the diagnostic listings among the visits/hospitalizations that occurred during the most recent 5 years is a modification on what has been done before [Citation42], however, our classification is stricter, as patients were only allowed to have CD or UC only in the past 5 years. One of the most widely used algorithms, developed by Benchimol et al. [Citation61] was also used for comparison. This IBD definition requires at least five diagnostic codes for IBD within 4 years in adult patients, and it bases the subclassification on the majority of last nine diagnoses. Using the Benchimol classification, only 38% of the Swedish IBD population could accurately be classified (data on request). The most likely reason why the Canadian definition cannot be used in Swedish data is that our registers do not include primary care, and that there is not full coverage of endoscopies in the National Patient Register, a fact that illustrates the difficulty in defining international generic classification schemes for IBD.

Health care utilization varies between countries and different classification algorithms need to be developed and investigated for each health care system. Different registers have their strengths and weaknesses and can be used for different research questions [Citation62]. In patients who change diagnosis the ‘true’ subtype varies over time. The time point at which follow-up should start in prospective studies (when IBD subtype is exposure) is most logically date of first diagnosis, but – in patients who change diagnosis – an alternative is to start follow-up at the date of diagnostic change and to calculate time at risk for each IBD subtype within the patient’s follow-up time.

In most case-control-studies we would use the ‘incident’ definition, but in a study where the ‘true’ IBD subtype is the essential outcome, it would be possible to use the ‘prevalent’ IBD classification, defined at the end of follow-up. In such a study, the choice of length of look back period will depend on which exposure you want to study, and cases and controls need to have the same length of look back period. The risk of being reclassified with regard to IBD subtype will be heavily dependent on duration of follow up, as shown in Supplementary Table S8 and S9.

CD-specific codes, such as CD of the small bowel, and perianal disease, have not been used before in a classification system of IBD. In other studies almost half, 47%, of patients with CD have been reported to undergo intestinal resection within 10 years of diagnosis [Citation63], and 33% to develop perianal disease [Citation64], whereas in UC, surgery rates are lower (16% after 10 years) [Citation63]. Among the participants in this study, 60% of the adult patients and 59% of pediatric patients with CD who never changed diagnosis had one or more of the CD-specific diagnostic codes, in comparison to only 6–7% of the patients with UC. We therefore believe that CD-specific codes can be used to distinguish patients with probable CD.

A major strength of this study was the access to routinely collected nationwide data with virtually complete coverage, including surgeries. A limitation is the lack of data from primary care. However, patients with IBD in Sweden are usually handled by gastroenterologists in hospital-based outpatient clinics, and therefore it is unlikely that the addition of primary care would change our results in any major way. A Swedish study showed that only 3% of prevalent IBD patients in Stockholm had a primary care visit in 2013 with IBD as a main diagnosis [Citation65]. The CD-specific codes used in our study do not exclude UC or IBD-U, nor do they exclude other causes for surgery than IBD. There can be reasons other than IBD for which a patient is subject to a surgical procedure, and the use of surgical codes is a source of potential misclassification. We did not validate the IBD diagnoses against other sources of information, however, the Swedish National Patient Register has a high validity with PPV’s of 85–95% for most diagnoses [Citation47]. The use of two diagnostic listings in the National Patient Register has been validated against patient charts with a PPV of 93% (95%CI: 87–97) for IBD [Citation46].

Conclusions

Most patients with IBD in Sweden had the same subtype over time, but 18% changed diagnoses at some point. Among those who changed, 37% changed from UC to CD, 33% from CD to UC and 30% to or from IBD-U. The proportion of patients with IBD-U was larger in children than in adults and increased over calendar years in all age groups.

| Abbreviations | ||

| IBD | = | inflammatory bowel disease |

| CD | = | Crohns’s disease |

| UC | = | ulcerative colitis |

| IBD-U | = | inflammatory bowel disease unclassified |

| ICD | = | International Classification of Diseases |

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (65.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Regional Ethics Committee, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Magro F, Langner C, Driessen A, et al. European consensus on the histopathology of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn's Colitis. 2013;7:827–851.

- Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohn's Colitis. 2017;11:649–670.

- Gomollon F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. Eccojc. 2017;11:3–25.

- Bousvaros A, Antonioli DA, Colletti RB, et al. Differentiating ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease in children and young adults: report of a working group of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:653–674.

- IBD Working Group of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: recommendations for diagnosis – the Porto criteria. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:1–7.

- Prenzel F, Uhlig HH. Frequency of indeterminate colitis in children and adults with IBD – a metaanalysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:277–281.

- Abraham BP, Mehta S, El-Serag HB. Natural history of pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:581–589.

- Burisch J, Pedersen N, Čuković-Čavka S, et al. East-West gradient in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: the ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Gut. 2014;63:588–597.

- Meucci G, Bortoli A, Riccioli FA, et al. Frequency and clinical evolution of indeterminate colitis: a retrospective multi-centre study in northern Italy. GSMII (Gruppo di Studio per le Malattie Infiammatorie Intestinali). Europ J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:909–913.

- Vind I, Riis L, Jess T, et al. Increasing incidences of inflammatory bowel disease and decreasing surgery rates in Copenhagen City and County, 2003–2005: a population-based study from the Danish Crohn colitis database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1274–1282.

- Gearry RB, Richardson A, Frampton CM, et al. High incidence of Crohn's disease in Canterbury, New Zealand: results of an epidemiologic study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:936–943.

- Henriksen M, Jahnsen J, Lygren I, et al. Change of diagnosis during the first five years after onset of inflammatory bowel disease: results of a prospective follow-up study (the IBSEN Study). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1037–1043.

- Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Lewis JD, et al. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in a Northern California managed care organization, 1996-2002. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1998–2006.

- Romberg-Camps MJ, Hesselink-van de Kruijs MA, Schouten LJ, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Disease in South Limburg (the Netherlands) 1991–2002: incidence, diagnostic delay, and seasonal variations in onset of symptoms. J Crohn's Colitis. 2009;3:115–124.

- Ng SC, Tang W, Ching JY, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn's and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:158–165.e2.

- Nuij VJ, Zelinkova Z, Rijk MC, et al. Phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease at diagnosis in the Netherlands: a population-based inception cohort study (the Delta Cohort). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2215–2222.

- Bjornsson S, Tryggvason F, Jonasson JG, et al. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Iceland 1995–2009. A nationwide population-based study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1368–1375.

- Studd C, Cameron G, Beswick L, et al. Never underestimate inflammatory bowel disease: high prevalence rates and confirmation of high incidence rates in Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:81–86.

- Hammer T, Nielsen KR, Munkholm P, et al. The Faroese IBD Study: incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases across 54 years of population-based data. Eccojc. 2016;10:934–942.

- Ng SC, Leung WK, Shi HY, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease from 1981 to 2014: results from a territory-wide population-based registry in Hong Kong. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1954–1960.

- Sawczenko A, Sandhu BK, Logan RF, et al. Prospective survey of childhood inflammatory bowel disease in the British Isles. Lancet. 2001;357:1093–1094.

- Auvin S, Molinie F, Gower-Rousseau C, et al. Incidence, clinical presentation and location at diagnosis of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective population-based study in northern France (1988-1999). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:49–55.

- Turunen P, Kolho KL, Auvinen A, et al. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Finnish children, 1987-2003. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:677–683.

- Pozler O, Maly J, Bonova O, et al. Incidence of Crohn disease in the Czech Republic in the years 1990 to 2001 and assessment of pediatric population with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:186–189.

- Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Drummond HE, et al. Definition of phenotypic characteristics of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1114–1122.

- Hope B, Shahdadpuri R, Dunne C, et al. Rapid rise in incidence of Irish paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:590–594.

- Henderson P, Hansen R, Cameron FL, et al. Rising incidence of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Scotland. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:999–1005.

- Adamiak T, Walkiewicz-Jedrzejczak D, Fish D, et al. Incidence, clinical characteristics, and natural history of pediatric IBD in Wisconsin: a population-based epidemiological study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1218–1223.

- Martin-de-Carpi J, Rodriguez A, Ramos E, et al. Increasing incidence of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Spain (1996-2009): the SPIRIT Registry. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:73–80.

- Muller KE, Lakatos PL, Arato A, et al. Incidence, Paris classification, and follow-up in a nationwide incident cohort of pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:576–582.

- Malaty HM, Mehta S, Abraham B, et al. The natural course of inflammatory bowel disease-indeterminate from childhood to adulthood: within a 25 year period. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2013;6:115–121.

- Winter DA, Karolewska-Bochenek K, Lazowska-Przeorek I, et al. Pediatric IBD-unclassified is less common than previously reported; results of an 8-year audit of the EUROKIDS registry. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2145–2153.

- Rinawi F, Assa A, Eliakim R, et al. The natural history of pediatric-onset IBD-unclassified and prediction of Crohn's disease reclassification: a 27-year study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(5):558–563.

- Benchimol EI, Guttmann A, Griffiths AM, et al. Increasing incidence of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: evidence from health administrative data. Gut. 2009;58:1490–1497.

- Lehtinen P, Ashorn M, Iltanen S, et al. Incidence trends of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Finland, 1987-2003, a nationwide study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1778–1783.

- Benchimol EI, Mack DR, Nguyen GC, et al. Incidence, outcomes, and health services burden of very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:803–813.e7.

- Benchimol EI, Manuel DG, Guttmann A, et al. Changing age demographics of inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: a population-based cohort study of epidemiology trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1761–1769.

- Leddin D, Tamim H, Levy AR. Decreasing incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in eastern Canada: a population database study. BMC Gastroenterology. 2014;14:140.

- Bitton A, Vutcovici M, Patenaude V, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Quebec: recent trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1770–1776.

- Busch K, Ludvigsson JF, Ekstrom-Smedby K, et al. Nationwide prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Sweden: a population-based register study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:57–68.

- Ludvigsson JF, Busch K, Olen O, et al. Prevalence of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Sweden: a nationwide population-based register study. BMC Gastroenterology 2017;17:23.

- Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Svenson LW, et al. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1559–1568.

- Norgard BM, Nielsen J, Fonager K, et al. The incidence of ulcerative colitis (1995-2011) and Crohn's disease (1995-2012) – based on nationwide Danish registry data. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1274–1280.

- Larsen MD, Baldal ME, Nielsen RG, et al. The incidence of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis since 1995 in Danish children and adolescents <17 years - based on nationwide registry data. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:1100–1105.

- Ishige T, Tomomasa T, Hatori R, et al. Temporal trend of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: analysis of national registry data 2004–2013 in Japan. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65(4):e80–e82.

- Jakobsson GL, Sternegard E, Olen O, et al. Validating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the Swedish National Patient Register and the Swedish Quality Register for IBD (SWIBREG). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(2):216–221.

- Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450.

- Smedby B, Schiøler G. Health Classifications in the Nordic Countries. Historic development in a national and international perspective 2006. Copenhagen: Nordisk Medicinalstatistisk Komite; 2006.

- Socialstyrelsen. Klassifikation av Vårdåtga¨rder [KVÅ-2015] [cited 2016 November 21]. Available from: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/klassificeringochkoder/atgardskoderkva

- Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy AK, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:125–136.

- Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, et al. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24:659–667.

- Lophaven SN, Lynge E, Burisch J. The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Denmark 1980–2013: a nationwide cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:961–972.

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV, Jr., Colombel JF, et al. The natural history of adult Crohn's disease in population-based cohorts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:289–297.

- Burisch J, Kiudelis G, Kupcinskas L, et al. Natural disease course of Crohn's disease during the first 5 years after diagnosis in a European population-based inception cohort: an Epi-IBD study. Gut. 2018. pii: gutjnl-2017-315568. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315568.

- Carvalho RS, Abadom V, Dilworth HP, et al. Indeterminate colitis: a significant subgroup of pediatric IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:258–262.

- Bernstein CN, Shanahan F, Anton PA, et al. Patchiness of mucosal inflammation in treated ulcerative colitis: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:232–237.

- Morpurgo E, Petras R, Kimberling J, et al. Characterization and clinical behavior of Crohn's disease initially presenting predominantly as colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:918–924.

- Yantiss RK, Odze RD. Diagnostic difficulties in inflammatory bowel disease pathology. Histopathology. 2006;48:116–132.

- Malmborg P, Grahnquist L, Idestrom M, et al. Presentation and progression of childhood-onset inflammatory bowel disease in Northern Stockholm County. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1098–1108.

- Malmborg P, Hildebrand H. The emerging global epidemic of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease–causes and consequences. J Intern Med. 2016;279:241–258.

- Benchimol EI, Guttmann A, Mack DR, et al. Validation of international algorithms to identify adults with inflammatory bowel disease in health administrative data from Ontario, Canada. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:887–896.

- Bernstein CN. Large Registry Epidemiology in IBD. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1941–1949.

- Frolkis AD, Dykeman J, Negron ME, et al. Risk of surgery for inflammatory bowel diseases has decreased over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:996–1006.

- Schwartz DA, Loftus EV, Jr., Tremaine WJ, et al. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn's disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:875–880.

- Cars T, Wettermark B, Lofberg R, et al. Healthcare utilisation and drug treatment in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eccojc. 2016;10:556–565.