Abstract

Objectives: Anti-TNF agents are effective to treat perianal Crohn’s disease (CD). Evidence suggests that Crohn’s disease patients with perianal fistulas need higher infliximab (IFX) serum concentrations compared to patients without perianal CD to achieve complete disease control. Our aim was to compare anti-TNF serum concentrations between patients with actively draining and closed perianal fistulas.

Methods: A retrospective survey was performed in CD patients with perianal disease treated with IFX or adalimumab (ADL). Fistula closure was defined as absence of active drainage at gentle finger compression and/or fistula healing on magnetic resonance imaging.

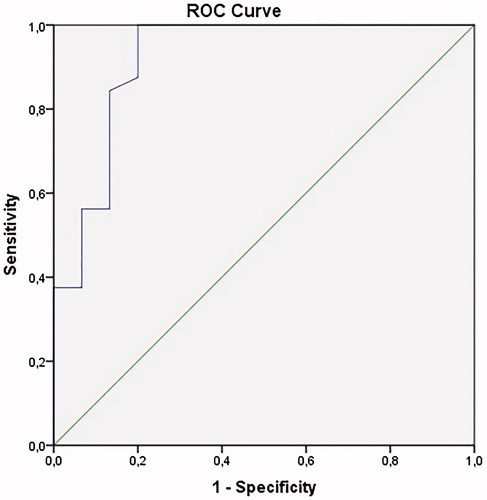

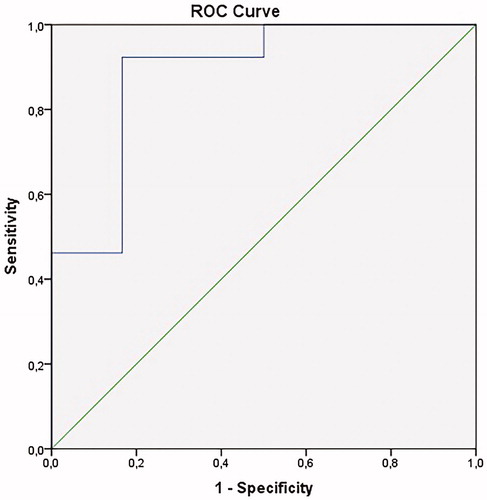

Results: We identified 66 CD patients with a history of perianal fistulas treated with IFX (n = 47) and ADL (n = 19). Median IFX serum trough concentrations ([interquartile range]) were higher in patients with closed fistulas (n = 32) compared to patients with actively draining fistulas (n = 15): 6.0 µg/ml [5.4–6.9] versus 2.3 µg/ml [1.1–4.0], respectively (p < .001)). A similar difference was seen in patients treated with ADL: median serum concentrations were 7.4 µg/ml [6.5–10.8] in 13 patients with closed fistulas versus 4.8 µg/ml [1.7–6.2] in 6 patients with producing fistulas (p = .003). Serum concentrations of ≥5.0 µg/ml for IFX (area under the curve of 0.92; 95% CI: 0.82–1.00)) and 5.9 µg/ml for ADL (area under the curve of 0.89; 95% CI 0.71–1.00) were associated with fistula closure.

Conclusion: Cut-off serum concentrations ≥5.0 µg/ml for IFX and ≥5.9 µg/ml for ADL were associated with perianal fistula closure. Hence, patients with producing perianal fistulas may benefit from anti-TNF dose intensification to achieve fistula closure.

Introduction

Perianal manifestations of Crohn’s disease (CD), such as fissures, fistulas and abscesses are invalidating complications, that are associated with a reduced quality of life [Citation1,Citation2]. Tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are not only effective for the treatment of luminal inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but also for perianal fistulas [Citation3–5]. Before the introduction of anti-TNF agents, the management of perianal fistulas in CD patients was mainly surgical. Surgical options include chronic seton drainage, fistulotomy, ligation of the intersfincteric fistula tract (LIFT) or mucosal advancement flaps. Many patients also undergo (temporary) seton placement to facilitate drainage and to prevent abscess recurrence. The therapeutic efficacy of infliximab (IFX) in CD patients with perianal fistulizing disease was demonstrated in the ACCENT-2 trial [Citation4]. IFX was effective in closing fistulas and during maintenance, the median duration of fistula closure was more than 3 months longer in responders receiving IFX compared to placebo.

In a meta-analysis of adalimumab (ADL) treatment for fistula closure in CD, complete fistula closure was observed in 36% of patients (95% CI: 0.31–0.41) and partial response in 31% (95% CI: 0.031–0.61) [Citation6]. The combination of anti-TNF treatment with temporary seton drainage is the preferred strategy to achieve fistula closure, since this approach leads to faster fistula healing and a higher likelihood to maintain fistula closure compared to surgical intervention alone [Citation7,Citation8]. However, reaching permanent fistula closure remains a challenge for both surgeons and gastroenterologists. The importance of adequate anti-TNF serum levels in order to achieve endoscopic remission in IBD patients has been investigated by several studies [Citation9–12]. However, increasing evidence suggests that CD patients with perianal fistulas might need higher anti-TNF serum levels compared to patients without fistulas [Citation13–15]. Up to now, the latter observation has only been reported for IFX. The aim of this study was to compare IFX and ADL steady-state serum levels in CD patients with actively producing versus closed perianal fistulas.

Methods

Study design

In this retrospective study, all patients with perianal fistulizing CD receiving IFX or ADL maintenance treatment at the Academic Medical Centre in Amsterdam between January 2016 and January 2017 with available serum concentrations were included. After identification, patients were divided into two groups based on the status of perianal fistulizing disease and based on the time point at which the serum drug concentrations were measured: actively draining or not actively draining perianal fistulas. Serum IFX and ADL concentrations were measured with enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA) and anti-drug antibody levels were determined using a radioimmunoassay antigen-binding test, which only detects anti-drug antibodies in the absence of drug (drug sensitive assay) at Sanquin Diagnostic Services, Biologics Lab (Amsterdam, the Netherlands) [Citation16,Citation17]. Fistula closure was defined as absence of purulent discharge upon gentle finger compression by the physician and/or fistula closure on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Fistulas on MRI were defined as closed if the fistula tract was described as fibrotic. For a patient to be eligible for analysis, physical examination of the fistula had to be well documented in the medical chart. Time between physical fistula examination/imaging and serum drug level measurement could not exceed four weeks. Patients who underwent surgical interventions (i.e., ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract surgery or faecal diversion procedure) during this timeframe and patients with internal fistulas were excluded. For IFX, only trough levels (TLs) were used. For ADL, all serum drug measurements between two injections were eligible for inclusion, since all patients were on maintenance treatment and reached steady state [Citation18]. Information about demographics, disease and treatment duration, fistula characteristics, dosing regimens, smoking status, immunogenicity and concomitant immunomodulator use was collected.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were used in order to describe baseline patient characteristics. The Mann–Whitney U Test was used for comparison of non-normally distributed variables. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was conducted to evaluate the accuracy of prediction of fistula closure by IFX an ADL levels and to determine cut-off values for serum drug levels and fistula closure. All reported p values were 2-sided, and p values <.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 24 statistical software [Armonk, New York, USA].

Results

Patient demographics

Sixty-six CD patients with perianal CD were identified. Forty-seven were treated with IFX and 19 with ADL. Patient characteristics are shown in and .

Table 1. Patient characteristics IFX treated group.

Table 2. Patient characteristics ADL treated group.

IFX treatment group

Median [interquartile range (IQR)] disease duration was 17 years (IQR: 6.0–24.0) in patients who received treatment with IFX (n = 47). Thirty-two out of 47 patients (68%) had closed perianal fistulas and the remaining 15 patients (32%) had actively producing fistulas. A significant difference was seen between median serum IFX TLs in patients with closed perianal fistulas compared to patients with actively producing fistulas (6.0 µg/ml [IQR: 5.4–6.9] versus 2.3 µg/ml [IQR: 1.1–4.0], p < .001) (). There were no patients with detectable anti-drug antibodies to IFX. An IFX TL ≥5 µg/ml was significantly associated with perianal fistula closure, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.82–1.00), p < .001) (). Moreover, higher fistula closure rates were seen in anti-TNF naïve patients and patients receiving combination therapy with an immunomodulator (p < .05). A longer disease duration and prior endoscopically proven proctitis were both associated with persistently active perianal fistulas (p = .01 and p = .001, respectively). IFX dosing regimens per treatment group are listed in .

Figure 1. Median IFX TLs of 47 patients with productive versus closed fistulas: 2.3 µg/ml versus 6.0 µg/ml. IFX: infliximab; TL: trough level; [IFX]: infliximab serum concentration; N: number of patients.

![Figure 1. Median IFX TLs of 47 patients with productive versus closed fistulas: 2.3 µg/ml versus 6.0 µg/ml. IFX: infliximab; TL: trough level; [IFX]: infliximab serum concentration; N: number of patients.](/cms/asset/e8948473-188d-40c2-974a-862d21933b03/igas_a_1600014_f0001_b.jpg)

Figure 2. Correlation between serum IFX trough levels and fistula closure. AUC: 0.92 (95% CI: 0.82–1.00), p < .001. IFX: infliximab; AUC: area under the curve; CI: confidence interval; ROC: receiver operating characteristic.

Table 3. Dosing regimen of 47 patients treated with infliximab (IFX).

ADL treatment group

Patients treated with ADL (n = 19) had a median disease duration of 10 years (IQR: 5.0–22.0). Thirteen patients (68%) had closed perianal fistulas compared to 6 patients (32%) with actively producing fistulas. Median serum ADL steady state levels were significantly higher in patients with closed fistulas compared to patients with actively producing fistulas (7.4 µg/ml [IQR: 6.5–10.8] versus 4.8 µg/ml [IQR: 1.7–6.2], p = .003) (). Similar to the IFX treatment group, none of the patients had detectable antibodies directed against ADL. For ADL, a cut off serum concentration of 5.9 µg/ml was associated with perianal fistula closure (AUC 0.89; 95% CI 0.71–1.00, p < .01) (). Initiation of ADL treatment combined with seton drainage and treatment duration were associated with fistula closure (p < .05). None of the patients with closed perianal fistulas had prior proctitis, compared to 33% of patients with actively producing fistulas. ADL dosing regimens per treatment group are listed in .

Figure 3. Median ADL serum levels of 19 patients with productive versus closed fistulas: 4.8 µg/ml versus 7.4 µg/ml. [IFX]: infliximab serum concentration; N: number of patients.

![Figure 3. Median ADL serum levels of 19 patients with productive versus closed fistulas: 4.8 µg/ml versus 7.4 µg/ml. [IFX]: infliximab serum concentration; N: number of patients.](/cms/asset/0afb78fc-780b-4975-98b5-d99a35dfd97d/igas_a_1600014_f0003_b.jpg)

Figure 4. Correlation between serum ADL levels and fistula closure. AUC: 0.89 (95% CI: 0.71–1.00), p < .01. ADL: adalimumab; AUC: area under the curve; ROC: receiver operating characteristic.

Table 4. Dosing regimen of 19 patients treated with adalimumab (ADL).

Discussion

In this study, we observed higher IFX and ADL serum levels in patients with closed perianal fistulas (confirmed by physical examination and/or MRI) compared to patients with actively producing fistulas.

The importance of seton drainage in combination with an anti-TNF agent in the treatment of perianal fistulas in CD patients is well known, although recurrence rates after initial closure remain high [Citation7,Citation8,Citation17]. The importance of adequate serum concentrations to achieve clinical, biochemical and endoscopic remission in IBD patients receiving treatment with anti-TNF agents is well established. For IFX, a TL cut-off >5 µg/ml is considered therapeutic during maintenance thrapy [Citation19,Citation20]. For ADL, steady-state serum levels >5 µg/ml are associated with mucosal healing [Citation18–21]. Interestingly, it seems that optimal cut-off points for anti-TNF serum levels may depend on the desired treatment goal (i.e., clinical remission, mucosal or fistula healing, etc.). It remains unclear if there is a maximum to therapeutic ranges of anti-TNF serum concentrations. Most evidence suggests that higher IFX doses are not associated with major side effects, such as an increased infection risk but an association between high IFX and ADL serum concentrations (i.e., >5.5 and 6.6 μg/ml, respectively) and impaired disease-specific quality of life in IBD patients has been found [Citation21–24]. Although treatment de-escalation seems attractive, also from an economic point of view, this approach should be applied with caution because individual patients may need higher serum levels than considered ‘therapeutic’ in the average population, presumably depending on the TNF load and regeneration.

The results of the present study demonstrate that higher anti-TNF levels are associated with higher rates of perianal fistula closure, which is in line with previous studies [Citation13,Citation14]. Davidov and colleagues found a positive association between IFX serum levels during induction therapy and perianal fistula closure in 36 patients [Citation14]. Patients with a positive effect on fistula closure after IFX initiation had higher IFX serum induction levels compared to patients without fistula closure. This finding was recently confirmed in a larger cohort of patients described by Yarur et al. in which higher IFX serum drug levels during maintenance treatment were found in patients with closed perianal fistulas compared to patients with actively producing fistulas (15.8 versus 4.4 µg/ml, respectively, p < .0001) [Citation13]. Moreover, they reported that patients with anti-drug antibodies, a phenomenon that is often associated with low serum drug levels, had a lower chance of achieving fistula healing (OR: 0.04 [95% CI: 0.005–0.3], p < .001). High local production of TNF in the fistula tract and in the surrounding tissue might explain the need for higher anti-TNF serum concentrations, but further research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

It has to be underlined that fistula closure was mainly based on physical examinations in this study, hence it was not known whether the entire fistula tract was really healed. Although MRI is frequently used to investigate fistula tracts and to confirm closure, there are still no universal criteria for describing fistula healing and closure on MRI. In a study performed by Tozer et al., a trend toward association between stopping IFX maintenance treatment and fistula recurrence was seen in patients with healed fistulas confirmed by MRI [Citation25]. The observation that inadequate drug-exposure can lead to re-opening of ‘closed’ fistula tracts suggests that these fistulas were perhaps not completely healed.

Our study has several limitations. The retrospective design is one of the major limitations of this study. All information about physical examination was extracted from medical charts. Fibrotic fistula tracts on MRI or fistula tracts with closed external openings described by the radiologist were considered as ‘closed fistulas on MRI’. No differentiation was made between complex and simple fistula tracts, because this was only described in the MRI report in a small proportion of patients. Although we could not differentiate between simple and complex fistulas, the main message of this paper is that patients with perianal CD need higher anti-TNF serum levels compared to patients without perianal disease, which has important clinical implications. Future studies should investigate whether the complexity of fistulas is of impact on how much drug is needed. Lastly, biochemical or endoscopic data were not included in the analysis, since there was a considerable amount of missing data or in case they were performed out of the specified time-frame.

In conclusion, cut-off serum concentrations of 5.0 µg/ml and 5.9 µg/ml for IFX and ADL respectively were associated with fistula closure. Our results confirm the findings from Yarur and colleagues who found an association between higher IFX trough levels and fistula healing in CD patients [Citation13]. To our knowledge, we are the first to report the same association for ADL. Hence, patients with actively producing perianal fistulas might benefit from anti-TNF treatment intensification to increase serum drug levels resulting in fistula closure but further prospective studies are needed to confirm these data.

| Abbreviations | ||

| ADL | = | Adalimumab |

| Anti-TNF | = | Anti-tumour necrosis factor |

| CRP | = | C-reactive protein |

| CD | = | Crohn’s disease |

| IBD | = | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| IFX | = | Infliximab |

| IQR | = | Interquartile range |

| LIFT | = | Ligation of the intersfincteric fistula tract |

| MRI | = | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| ROC | = | Receiver operating characteristic |

| SD | = | Standard deviation |

| TL | = | Trough level |

Disclosure statement

AS has no conflicts of interest.

ML has served as speaker and/or principal investigator for: Abbvie, Celgene, Covidien, Dr. Falk, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Protagonist Therapeutics, Receptos, Takeda, Tillotts, Tramedico. He has received research grants from AbbVie, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Achmea healthcare and ZonMW.

CB has no conflicts of interest.

KG has served as speaker and/or advisor for Amgen, AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ferring, Hospira, MSD, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Takeda and Tigenix.

CP has received grant support from Takeda, Dr Falk Pharma, speaker’s fee from Abbvie, Takeda, Ferring and Dr Falk Pharma, consultancy from Abbvie and Takeda

WB has no conflicts of interest.

GD has served as advisor for Abbvie, Ablynx, Allergan, Amakem, Amgen, AM Pharma, Arena Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, Avaxia, Biogen, Bristol Meiers Squibb, Boerhinger Ingelheim, Celgene/Receptos, Celltrion, Cosmo, Covidien/Medtronics, Ferring, DrFALK Pharma, Eli Lilly, Engene, Galapagos, Genentech/Roche, Gilead, Glaxo Smith Kline, Hospira/Pfizer, Immunic, Johnson and Johnson, Lycera, Medimetrics, Millenium/Takeda, Mitsubishi Pharma, Merck Sharp Dome, Mundipharma, Nextbiotics, Novonordisk, Otsuka, Pfizer/Hospira, Photopill, Prometheus laboratories/Nestle, Progenity, Protagonist, Robarts Clinical Trials, Salix, Samsung Bioepis, Sandoz, Seres/Nestle, Setpoint, Shire, Teva, Tigenix, Tillotts, Topivert, Versant and Vifor; received speaker fees from Abbvie, Biogen, Ferring, Johnson and Johnson, Merck Sharp Dome, Mundipharma, Norgine, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Shire, Millenium/Takeda, Tillotts and Vifor.

References

- Makowiec F, Jehle EC, Starlinger M. Clinical course of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1995;37:696–701.

- Schwartz DA, Loftus EV Jr. Tremaine WJ, et al. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:875–880.

- Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(18):1398–405.

- Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876–885.

- Tozer PJ, Burling D, Gupta A, et al. Review article: medical, surgical and radiological management of perianal Crohn’s fistulas. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:5–22.

- Fu YM, Chen M, Liao AJ. A Meta-Analysis of Adalimumab for Fistula in Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterol Res. 2017;2017:1745692.

- Sciaudone G, Di Stazio C, Limongelli P, et al. Treatment of complex perianal fistulas in Crohn disease: infliximab, surgery or combined approach. Can J Surg. 2010;53:299–304.

- Regueiro M, Mardini H. Treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease with infliximab alone or as an adjunct to exam under anesthesia with seton placement. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:98–103.

- Yarur AJ, Kubiliun MJ, Czul F, et al. Concentrations of 6-thioguanine nucleotide correlate with trough levels of infliximab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease on combination therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(6):1118–24.e3.

- Maser EA, Villela R, Silverberg MS, et al. Association of trough serum infliximab to clinical outcome after scheduled maintenance treatment for Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1248–1254.

- Chaparro M, Guerra I, Munoz-Linares P, et al. Systematic review: antibodies and anti-TNF-alpha levels in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:971–986.

- Ungar B, Levy I, Yavne Y, et al. Optimizing Anti-TNF-alpha therapy: serum levels of infliximab and adalimumab are associated with mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:550–557.e2.

- Yarur AJ, Kanagala V, Stein DJ, et al. Higher infliximab trough levels are associated with perianal fistula healing in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:933–940.

- Davidov Y, Ungar B, Bar-Yoseph H, et al. Association of induction infliximab levels with clinical response in perianal crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:549–555.

- El-Matary W, Walters TD, Huynh HQ, et al. Higher Postinduction Infliximab Serum Trough Levels Are Associated With Healing of Fistulizing Perianal Crohn’s Disease in Children. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(1):150–155.

- Wolbink GJ, Vis M, Lems W, et al. Development of antiinfliximab antibodies and relationship to clinical response in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:711–715.

- Aalberse RC, Dieges PH, Knul-Bretlova V, et al. IgG4 as a blocking antibody. Clin Rev Allergy. 1983;1:289–302.

- Ungar B, Engel T, Yablecovitch D, et al. Prospective observational evaluation of time-dependency of adalimumab immunogenicity and drug concentrations: the poetic study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(6):890–898.

- Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, Kupfer SS, et al. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:827–834.

- Vande Casteele N, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, et al. Trough concentrations of infliximab guide dosing for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(7):1320–9.e3.

- Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infection and mortality in patients with crohn’s disease: more than 5 years of follow-up in the TREATTM registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1409–1422.

- Hendler SA, Cohen BL, Colombel J-F, et al. High-dose infliximab therapy in crohn’s disease: clinical experience, safety, and efficacy. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2015;9(3):266–275.

- Brandse JF, Vos LMC, Jansen J, et al. Serum concentration of anti-TNF antibodies, adverse effects and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission on maintenance treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9(11):973–981.

- Adedokun OJ, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Association between serum concentration of infliximab and efficacy in adult patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(6):1296–1307.

- Tozer P, Ng SC, Siddiqui MR, et al. Long-term MRI-guided combined anti-TNF-α and thiopurine therapy for crohn’s perianal fistulas. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(10):1825–1834.