Abstract

Background: Thioguanine is associated with liver toxicity, especially nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH). We assessed if liver histology alters during long-term maintenance treatment with thioguanine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Methods: Liver specimens of thioguanine treated IBD patients with at least two liver biopsies were revised by two independent liver pathologists, blinded to clinical characteristics. Alterations in histopathological findings between first and sequential liver specimen were evaluated and associated clinical data, including laboratory parameters and abdominal imaging reports, were collected.

Results: Twenty-five IBD patients underwent sequential liver biopsies prior to, at time of, or after cessation of thioguanine treatment. The median time between the first and second biopsy was 25 months (range: 14–54). Except for one normal liver specimen, any degree of irregularities including inflammation, steatosis, fibrosis and some vascular disturbances were observed in the biopsies. The rates of perisinusoidal fibrosis (91%), sinusoidal dilatation (68%) and nodularity (18%) were the same in the first and second liver biopsies. A trend towards statistical significance was observed for phlebosclerosis (36% of the first vs. 68% of the second biopsies, p = .092). Presence of histopathological liver abnormalities was not associated with clinical outcomes. Furthermore, two patients in this cohort had portal hypertension in presence of phlebosclerosis. In another two patients, nodularity of the liver resolved upon thioguanine withdrawal.

Conclusion: Vascular abnormalities of the liver were commonly observed in thioguanine treated IBD patients, although these were not progressive and remained of limited clinical relevance over time.

Introduction

Azathioprine and mercaptopurine, both as monotherapy or in combination with biologicals, are well established immunosuppressive drugs for the maintenance treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [Citation1–3]. Up to 50% of the azathioprine or mercaptopurine using patients discontinue treatment with these drugs, mainly due to adverse events [Citation4]. Thioguanine (TG), an equally effective but better-tolerated thiopurine-derivative, has been proposed as an alternative treatment option for patients who failed previous traditional therapies [Citation5–7].

Despite potential therapeutic benefit, TG treatment has largely been discarded due to its association with liver toxicity, mainly nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH), a cause of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension [Citation8]. In recent studies, drug-induced liver injury appeared to be dose-dependent and substantially lower during the currently advocated TG dosages (0.2–0.3 mg/kg, not exceeding 25 mg/day) [Citation9,Citation10]. Furthermore, it had been observed that histopathological vascular abnormalities such as NRH rarely led to symptoms of portal hypertension or liver transplantation, and were clinically insignificant in most patients [Citation10–12].

The disease course of TG associated liver toxicity, both at time of exposure and after withdrawal, remains poorly understood. In a recent study on the long-term prognosis of NRH in IBD patients who had been treated with thiopurines including TG, liver chemistry and blood count normalized in the majority, and symptoms of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension resolved in one-third of patients [Citation13]. In contrast, in a small study comprising ten children who had been treated with high dose TG for acute lymphatic leukemia, thrombocytopenia and esophageal varices did not improve upon drug withdrawal [Citation14]. It is possible that clinical outcomes reflect alterations in liver histopathology, but this remains unsubstantiated. The aim of the present study was to assess histopathological findings in sequential liver biopsies from TG treated IBD patients to evaluate if alterations in histopathology progress with time. Subsequently, we evaluated if alterations in liver histopathology coexisted with clinical signs or symptoms.

Material and methods

Study design and patient selection

Between 2002 and 2014, clinicians from seven different hospitals in the Netherlands (merged in a collaborative network on optimization of thiopurines in IBD) included TG treated patients who underwent a liver biopsy in a cohort database. These were patients who received TG for gastrointestinal diseases such as refractory celiac disease, microscopic colitis, ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Thioguanine was prescribed off-label according to the expert-based guidelines provided by the European TG working party [Citation5] (0.2–0.3 mg/kg, not exceeding 25 mg/day) to patients who failed previous conventional thiopurines due to toxicity or therapeutic refractoriness.

Adult patients (18 years and older) with IBD and at least two available biopsy specimens, obtained either prior to, at time of, or after TG withdrawal, were included in this retrospective analysis. In this manner, at least one liver biopsy was always conducted during TG treatment. Thioguanine treated patients with celiac disease and microscopic colitis were excluded from the analysis to decrease study heterogeneity.

Liver histopathology

All liver specimens were obtained using percutaneous needle biopsies. Biopsy specimens with the following staining were included in the analyses; hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and/or periodic acid-Schiff diastase (PAS-D) staining, Sirius red or Masson’s trichrome, collagen staining such as Elastic van Gieson (EvG) and reticulin silver staining. Additionally, only biopsy specimens with six or more portal tracts were included as these were considered adequate for histopathological evaluation [Citation15]. Because severe steatosis or steatohepatitis could change the architect of the cytoskeleton and hamper proper histopathological assessment, these biopsy specimens were excluded from the analysis [Citation16].

Liver biopsy specimens were revised by two independent liver pathologists (JV and EB) specialized in vascular abnormalities of the liver. They were both blinded, i.e., liver biopsies were revised without information about the clinical characteristics. In case of discrepancy between the pathologists, biopsies were jointly revised and the score was decided by consensus. Evaluation of the liver specimens included presence of histopathological and vascular irregularities such as sinusoidal dilatation, nodularity, perisinusoidal fibrosis, phlebosclerosis and perivenular fibrosis and were scored in an ordinal manner (). Together with these characteristics also portal-, interface-, and lobular inflammation, fibrosis and steatosis (Brunt’s score) [Citation17] were scored. In accordance with the definition as proposed by Wanless [Citation11] and Jharap et al. [Citation15], NRH was defined as grade 3 nodularity (visible on both hematoxylin-eosin and reticuline staining) in the absence of bridging fibrosis.

Table 1. Grading of histopathological characteristics.

Laboratory tests and medical imaging

Laboratory tests including hemoglobin, platelet count, white blood cell count, mean cellular volume, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl-transferase and, when available, 6-thioguanine nucleotides were collected around the time of the liver biopsies. Thrombocytopenia was defined as platelet count of <150 × 109/L and leukocytopenia as white blood cell count of <3.0 × 109/L. Liver test abnormalities were defined as any available liver enzyme test above the upper limit of the normal range, i.e., aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase or gamma-glutamyl-transferase >40 U/L or alkaline phosphatase >120 U/L. Reports of abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed within 3 months from the biopsy were also collected.

Statistical analysis

Clinical and histopathological characteristics were descriptively presented as numbers with percentages, means with standard deviations (SD) or medians with ranges, according to their distribution. To compare continuous variables between groups independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used where appropriate. Paired variables such as laboratory values were compared using the paired T-test or Wilcoxon signed rank test was used. Histopathological characteristics were dichotomized to reduce the amount of cells with very few cases. Crosstables with McNemar’s test were used to compare these dichotomous paired variables. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 20.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Two-tailed probability (p) values below .05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval (reference number 2012/8; 4 April 2012) was granted by the research medical ethics committee of the VU university medical center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a prior approval by the institution’s human research committee. Whereas data were provided anonymously, written informed consent was waived by the research medical ethics committee.

Results

Patient population

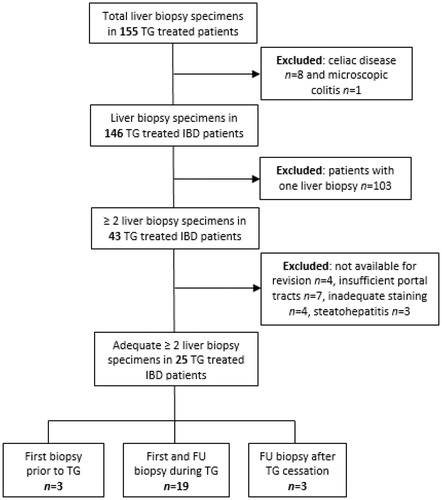

At time of analysis, the cohort consisted of 155 patients who underwent a liver biopsy including nine patients without IBD. These were excluded. Another 103 patients with only one biopsy were excluded as well. The remaining 43 IBD patients underwent at least two sequential liver biopsies prior to, at time of, or after cessation of TG therapy and were eligible for revision. In eleven patients, a third biopsy and in two patients, a fourth biopsy was available.

During the revision of the 43 liver biopsies, four specimens were not available for revision, another four were not stained adequately and three specimens revealed steatohepatitis. These 18 liver specimens were excluded from the final analysis. Out of 25 patients with at least two sequential liver biopsies with sufficient quality, four patients had three, and one patient had four liver biopsies available (). In 19 patients (out of 25, 76%), both first and follow-up liver biopsies were performed at time of TG treatment. In three patients (12%), the first liver specimen was obtained prior to TG, and the follow-up specimen during TG treatment. Another three patients underwent a first biopsy at time of TG treatment and a following biopsy after TG withdrawal.

Clinical characteristics

Among the 25 patients, ten (40%) were male and 15 (60%) had Crohn’s disease (). The mean age was 44 years (SD: 13). Indications for a second liver biopsy was part of routine toxicity screening protocol in 17 (68%), existence or worsening of liver test abnormalities in five (20%) and to evaluate histopathology after cessation of TG in three other patients (12%).

Table 2. Patient and disease characteristics.

Thioguanine and co-treatments

Thioguanine was prescribed in a mean daily dose of 20 mg (SD: 3.5) corresponding with 0.28 mg/kg (range: 0.10–0.38). Median treatment duration between start of TG therapy and the first liver biopsy was 16 months (range: 12–39) and between start of TG and the second liver biopsy was 41 months (13–72). The median time between first and sequential liver biopsy was 25 months (14–54). Adverse events were reported in five out of 25 patients (20%) including hepatotoxicity in three (12%), melanoma in one (4%) and myalgia in another patient (4%). All three patients with hepatotoxicity ceased treatment, whereas the patients with melanoma and the patient with myalgia continued TG. Co-treatments included infliximab in three (12%), budesonide in five (20%) and prednisolone in seven patients (28%) (≤10 mg/d in five and >10 mg/d in two patients).

Histopathological findings during thioguanine treatment

In 22 patients, the follow-up biopsy was obtained at time of TG treatment. The first liver specimens of these patients contained a median of 9 portal tracts (range: 6–20) and had a mean length of 14.0 mm (SD: 6.2). The second liver specimens contained a median of 15 portal tracts (range: 8–32) and had a mean length of 15.4 mm (SD: 6.7).

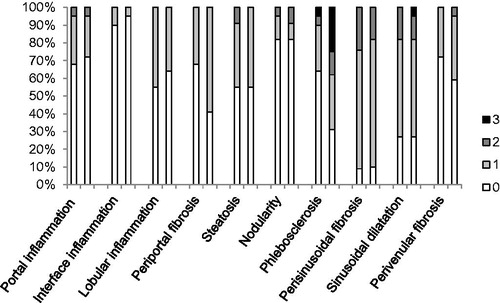

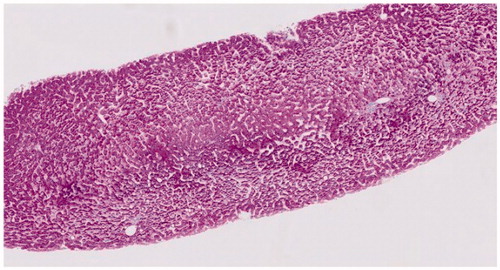

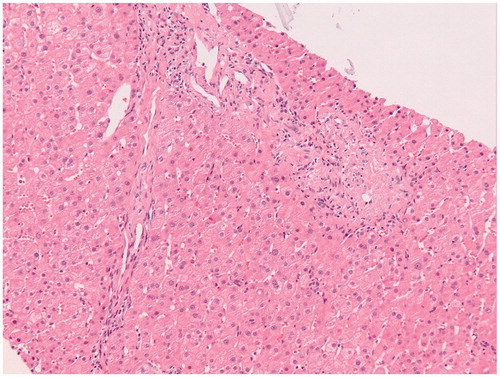

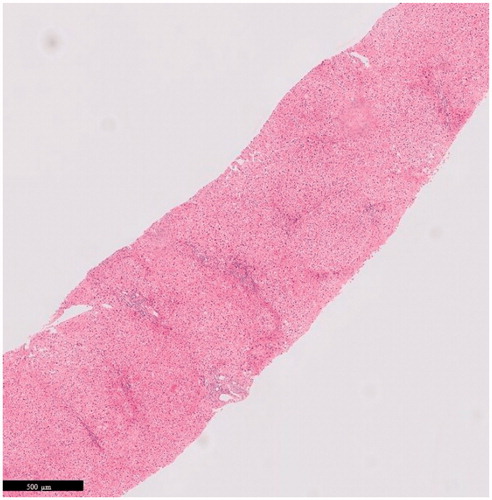

Except for one normal liver biopsy specimen, irregularities such as vascular disturbances, inflammation, steatosis and fibrosis, were present in any degree in the revised liver biopsy specimens. The observed histopathological abnormalities in the first and second biopsy are depicted in using a bar chart. No statistical significant differences in vascular abnormalities were found between the first and second biopsy specimens: hepatic sinusoidal dilatation was found in 68% in both biopsies, nodularity in 18% and perisinusoidal fibrosis in 91% in both biopsies. A trend towards statistical significance was observed for phlebosclerosis (36% of the first vs. 68% of the second biopsies, p = .092). Microscopic examination of a liver biopsy with hepatic sinusoidal dilatation is shown in and of phlebosclerosis in .

Figure 2. Histopathological findings as observed in sequential liver biopsies obtained during thioguanine treatment. Histopathological abnormalities were graded from 0 to 3 according to the characteristics depicted in . The first and second bars represent the observed histopathological abnormalities in the first and second biopsy, respectively. No statistical significant differences between the first and second biopsy specimens were found although a trend towards statistical significance was observed for phlebosclerosis.

Figure 3. Microscopic examination of a liver biopsy with hepatic sinusoidal dilatation. Histopathology of a liver biopsy with hepatic sinusoidal dilatation characterized by widening of hepatic sinusoids in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease during thioguanine treatment (Hematoxylin-Eosin stained).

Figure 4. Microscopic examination of a liver biopsy with phlebosclerosis. Histopathology of a liver biopsy with phlebosclerosis characterized by sclerosis of the portal tract with diminished caliber of the portal vein caliber and extraportal shunt vessels in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease treated with thioguanine (Hematoxylin-Eosin stained).

Minor histopathological alterations between first and second biopsy evolved in both directions: some irregularities were observed more frequent whereas others were less frequently seen in the second biopsy (). This also considered patients who had a third and fourth biopsy (Supplemental Table 1). None of the liver biopsy specimens of the 22 patients fulfilled the criteria of grade 3 NRH although grade 1 or 2 NRH was observed in six patients (27%). In two patients, nodularity was observed in both biopsies, in two patients nodularity was present in the first biopsy but not in the second and in another two patients there was no nodularity in the first biopsy but it was present in the second biopsy. Microscopic examination of a liver biopsy with NRH is shown in .

Figure 5. Microscopic examination of a liver biopsy with nodular regenerative hyperplasia (NRH). Histopathology of a liver biopsy with NRH characterized by nodules of hypertrophic hepatocytes surrounded by a rim of atrophic liver plates with compression of sinusoids in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease treated with thioguanine without signs of (non-cirrhotic) portal hypertension (Hematoxylin-Eosin stained).

Table 3. Histopathological irregularities of the liver and their progression during time of TG treated IBD patients (n = 22).

Clinical findings during thioguanine treatment

Overall, an increase in hemoglobin concentrations was observed during TG treatment (). Thrombocytopenia was observed in three patients (12%). In patient #1, thrombocytopenia was preexisting as asymptomatic, and liver histopathology showed grade 1 nodularity in the first and grade 2 in the second liver biopsy. Patient #2 and #3 had preexisting splenomegaly and liver test abnormalities and developed in addition to this thrombocytopenia during TG treatment. Both patients had some nodularity and phlebosclerosis in the sequential liver biopsy specimens. The degree of nodularity increased in patient #2 (from grade 0 in the first to grade 2 in the second biopsy) and decreased in patient #3 (from grade 2 in the first to grade 1 in the second biopsy). The degree of phlebosclerosis was grade 2 in both liver biopsies of patient #2 and increased from grade 1 to grade 2 in patient #3. There were no other cases of splenomegaly or other symptoms of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension observed in this cohort.

Table 5. Histopathological and clinical alterations in 3 patients who ceased thioguanine due to hepatotoxicity.

At time of first liver and second liver biopsy, nine (26%) and five (20%) patients had liver test abnormalities, respectively. Three patients had liver test abnormalities at both time points, including aforementioned patients #2 and #3 with preexisting splenomegaly and histopathological liver abnormalities. The other patient with persisting liver abnormalities had moderate steatosis in both biopsies. Two patients developed liver test abnormalities whilst on TG treatment including a patient who developed mild steatosis and a gamma-glutamyl-transferase concentration of 43 U/L. The other patient had developed grade 1 nodularity, grade 2 perisinusoidal fibrosis and grade 3 phlebosclerosis together with an isolated increase of gamma-glutamyl-transferase level of 92 U/L at time of second biopsy. These abnormalities were not present at the first liver biopsy. Abdominal imaging was not available in both patients.

Histopathology and clinical findings after thioguanine withdrawal

Three patients, all female with Crohn’s disease, had a first liver biopsy at time of TG and a second biopsy after cessation of treatment due to hepatotoxicity. The clinical and histopathological characteristics of these patients are depicted in . Time between start of TG therapy and first biopsy was 18, 21 and 25 months, respectively. Time between TG withdrawal and the second biopsy was 21, 8 and 17 months, respectively. Histopathology of the first biopsy revealed mild steatosis in one and NRH in two patients. At time of the biopsies, they all displayed liver test abnormalities and one NRH patient had thrombocytopenia as well. In the two patients with characteristics of NRH at the first biopsy, the second biopsies showed less phlebosclerosis, perisinusoidal fibrosis and nodularity. These two patients also had an improvement of liver test abnormalities. The third patient with a second biopsy after TG withdrawal had the same degree of (mild) steatosis in his follow-up biopsy. There were no other clinical or histopathological abnormalities in this patient, hence the persisting liver test abnormalities were related to the fatty liver disease.

Discussion

In this study, we observed that histopathological characteristics such as mild inflammation, steatosis, fibrosis and vascular irregularities of the liver were commonly observed in TG treated IBD patients, but were mainly asymptomatic and non-progressive over time whilst continuing treatment. We observed the same rates of perisinusoidal fibrosis (91%), sinusoidal dilatation (68%) and nodularity (18%) in the first and sequential liver biopsies and a trend towards statistical significance for phlebosclerosis (36% of the first vs. 68% of the second biopsies, p = .092). Nodularity, in any degree, was present in six patients (27%) and worsened or diminished in an equal number of patients. Furthermore, two patients in this cohort had portal hypertension in the presence of phlebosclerosis. In another two patients, nodularity of the liver resolved upon thioguanine withdrawal.

The pathogenesis of NRH and comparable vascular liver disorders which may cause non-cirrhotic portal hypertension is incompletely elucidated, but seems to be related to circulatory disruption in the hepatic blood flow due to obliterative vasculopathy or secondary to damage of sinusoidal endothelial cells [Citation18]. The clinical and the histological course of NRH is poorly described, however, these data may be of value to establish an optimal approach to patients with NRH and comparable vascular liver disorders. With these sequential liver biopsies, we aimed to evaluate the course of vascular histopathological liver irregularities in TG treated patients, and relate these findings to clinical characteristics. The median time between first and follow-up biopsy was about two years which seems long enough to assess evolution or progression of therapy-associated toxicity, when relating to literature reports on TG induced liver toxicity [Citation8].

To increase reproducibility of this study, revision of the specimens was done independently by two experienced liver pathologists blinded to clinical characteristics. However, due to high probability of introduced selection bias, our results should be interpreted with caution. The indication for a follow-up biopsy depends strongly on the clinical well-being of a patient. Therefore, patients with a normal first biopsy might have been less eligible to undergo a second biopsy. Contrarily, a first biopsy with signs of relevant liver injury might have led to cessation of TG treatment without performing a second biopsy. Furthermore, we did not have comparison groups to evaluate possible risk factors of vascular liver irregularities and draw firm conclusions about causality. Especially, since all patients were previously exposed to azathioprine or mercaptopurine, and these drugs as well as IBD itself, have been associated with the development of NRH-like liver abnormalities [Citation19–21]. Last, sampling errors could not be ruled out given the nature of needle biopsy specimens.

In this present study, as our previous histopathological study, mild histopathological abnormalities such as vascular irregularities were frequently observed in TG treated IBD patients [Citation10]. In another study, we demonstrated that histopathological abnormalities were also common among thiopurine-naïve IBD patients, reflecting the high background prevalence of these abnormalities in selected series [Citation19]. In all studies, the association between histopathological findings and clinical characteristics was poor. This also concerned the degree of nodularity of the liver and NRH in particular. We also showed that clinical relevant liver injury during TG treatment is not always the result of NRH, but may be caused by other (vascular) histopathological abnormalities such as phlebosclerosis as observed in two patients with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension in our cohort. Before, Wanless and Aggarwal et al. already described that nodularity often coexisted with phlebosclerosis, the main histopathological characteristic of obliterative portal venopathy, which has been associated with non-cirrhotic portal hypertension as well [Citation11,Citation22].

Furthermore, we observed that histopathological changes of the liver, together with liver tests and platelet counts, might improve upon TG withdrawal. The reversibility of NRH-like abnormalities has been acknowledged before. In an Austrian study, liver biopsies together with hepatic venous pressure gradient measurements were systematically performed in 24 TG treated IBD patients [Citation23]. Six of these patients (25%) had histopathological findings of NRH, of whom three patients had concomitant elevated hepatic venous pressure gradient values. One year after discontinuation of TG therapy, hepatic venous pressure gradient values improved in all three patients. In a study on the long-term prognosis of NRH in IBD patients who had been treated with thiopurines, liver tests and blood counts normalized in the majority, and symptoms of non-cirrhotic portal hypertension resolved in one-third of patients during a median time of 5.5 years [Citation13].

In conclusion, we demonstrated that vascular liver abnormalities of any degree were commonly observed in long-term TG treated IBD patients, but these were rarely progressive and of limited clinical relevance.

Author contributions

Guarantor of the article: AAvB.

DpvA, NKHdB, BJ and AavB conceived the study. DpvA and BJ collected the data. EB and JV revised all biopsy specimens. NKHdB, GH, DW, MB, MGR, CMvN, CJJM and AvB included patients in the study. DpvA and MS drafted the manuscript. DpvA and BILW analyzed the data. KHNdB, BJ, EB, GH, DW, MB, MGR, CMvN, CJJM, JV and AvB critically revised the manuscript. All authors commented on drafts of the paper. All authors have approved the final draft of the article.

Table 4. Laboratory findings at time of first and second liver biopsy.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (55.4 KB)Disclosure statement

DP van Asseldonk has served as a consultant for Takeda, received speakers fee from Dr. Falk and received unrestricted research Grants from Dr. Falk and Janssen. He performed as a principal investigator in a study sponsored by Gilead.

M Simsek has received an unrestricted research Grant from TEVA Pharma B.V.

NKH de Boer has served as a speaker for AbbVie, Takeda and MSD. He has served as a consultant and principal investigator for Takeda and TEVA Pharma B.V. He has received an unrestricted research Grant from Dr. Falk and Takeda.

B Jharap, G den Hartog, D Westerveld, M Becx, MG Russel, BI Lissenberg-Witte, CM van Nieuwkerk, J Verheij have nothing to declare.

CJJ Mulder has served as consultant and principal investigator for TEVA Pharma B.V.

AA van Bodegraven has served as consultant or speaker for AbbVie, Ferring, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer, Takeda, TEVA, Tramedico, VIFOR, and Dutch Ministry of Health (ZonMW). He has received unrestricted research Grants from Aventis and Ferring, and the Dutch Ministry of Health. He performed as principal investigator in studies sponsored by Schering-Plough, Roche, Teva, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer and Centocor.

References

- Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571–607.

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–1395.

- Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Middleton S, et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:392–400.e3.

- Jharap B, Seinen ML, de Boer NK, et al. Thiopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease patients: analyses of two 8-year intercept cohorts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1541–1549.

- de Boer NK, Reinisch W, Teml A, et al. 6-Thioguanine treatment in inflammatory bowel disease: a critical appraisal by a European 6-TG working party. Digestion. 2006;73:25–31.

- NKH d. B, Thiopurine Working Group, Ahuja V, et al. Thiopurine therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases: making new friends should not mean losing old ones. Gastroenterology. 2018;156:11–14.

- Simsek M, Deben DS, Horjus CS, et al. Sustained effectiveness, safety and therapeutic drug monitoring of tioguanine in a cohort of 274 IBD patients intolerant for conventional therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019.

- Dubinsky MC, Vasiliauskas EA, Singh H, et al. 6-thioguanine can cause serious liver injury in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:298–303.

- Oancea I, Png CW, Das I, et al. A novel mouse model of veno-occlusive disease provides strategies to prevent thioguanine-induced hepatic toxicity. Gut. 2013;62:594–605.

- van Asseldonk DP, Jharap B, Verheij J, et al. The prevalence of nodular regenerative hyperplasia in inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with thioguanine is not associated with clinically significant liver disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2112–2120.

- Wanless IR. Micronodular transformation (nodular regenerative hyperplasia) of the liver: a report of 64 cases among 2,500 autopsies and a new classification of benign hepatocellular nodules. Hepatology. 1990;11:787–797.

- Meijer B, Simsek M, Blokzijl H, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia rarely leads to liver transplantation: a 20-year cohort study in all Dutch liver transplant units. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2017;5:658–667.

- Simsek M, Meijer B, Ramsoekh D, et al. Clinical course of nodular regenerative hyperplasia in thiopurine treated inflammatory bowel disease patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;17:568–570.

- Rawat D, Gillett PM, Devadason D, et al. Long-term follow-up of children with 6-thioguanine-related chronic hepatoxicity following treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53:478–479.

- Jharap B, van Asseldonk DP, de Boer NK, et al. Diagnosing nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the liver is thwarted by low interobserver agreement. PloS One. 2015;10:e0120299.

- Caldwell S, Lackner C. Perspectives on NASH Histology: cellular ballooning. Ann Hepatol. 2017;16:182–184.

- Brunt EM, Janney CG, Bisceglie AM, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterology. 1999;94:2467–2474.

- Hartleb M, Gutkowski K, Milkiewicz P. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia: evolving concepts on underdiagnosed cause of portal hypertension. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1400–1409.

- De Boer NK, Tuynman H, Bloemena E, et al. Histopathology of liver biopsies from a thiopurine-naive inflammatory bowel disease cohort: prevalence of nodular regenerative hyperplasia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:604–608.

- Daniel F, Cadranel JF, Seksik P, et al. Azathioprine induced nodular regenerative hyperplasia in IBD patients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005;29:600–603.

- Vernier-Massouille G, Cosnes J, Lemann M, et al. Nodular regenerative hyperplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with azathioprine. Gut. 2007;56:1404–1409.

- Aggarwal S, Fiel MI, Schiano TD. Obliterative portal venopathy: a clinical and histopathological review. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2767–2776.

- Ferlitsch A, Teml A, Reinisch W, et al. 6-thioguanine associated nodular regenerative hyperplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease may induce portal hypertension. Am J Gastroenterology. 2007;102:2495–2503.