Abstract

Objective: There is little information on cost-of-illness among patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) in Denmark. The objective of this study was to estimate the average 5-year societal costs attributable to CD or UC patients in Denmark with incidence in 2003–2015, including costs related to health care, prescription medicine, home care and production loss.

Materials and methods: A national register-based, cost-of-illness study was conducted using an incidence-based approach to estimate societal costs. Incident patients with CD or UC were identified in the National Patient Registry and matched with a non-IBD control from the general population on age and sex. Attributable costs were estimated applying a difference-in-difference approach, where the total costs among individuals in the control group were subtracted from the total costs among patients.

Results: CD and UC incidence fluctuated but was approximately 14 and 31 per 100,000 person years, respectively. The average attributable costs were highest the first year after diagnosis, with costs equalling €12,919 per CD patient and €6,501 per UC patient. Hospital admission accounted for 36% in the CD population and 31% in the UC population, the first year after diagnosis. Production loss exceeded all other costs the third-year after diagnosis (CD population: 52%; UC population: 83%).

Conclusions: We found that the societal costs attributable to incident CD and UC patients are substantial compared with the general population, primarily consisting of hospital admission costs and production loss. Appropriate treatment at the right time may be beneficial from a societal perspective.

Introduction

The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), encompassing both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), has continued to rise throughout the world, affecting 0.2–0.5% of the general population [Citation1]. Disease onset typically occurs between the ages of 15–35 years for CD and 30–40 for UC, with no gender-specific distribution [Citation2,Citation3]. As IBD prevalence continues to increase, understanding the cost-of-illness from a societal perspective becomes important for decision makers to ensure patients receive the right treatments.

A study in 2008 estimated that the total economic burden of CD was between €2.1 and €16.7 billion in Europe, and $10.9–$15.5 billion in the United States [Citation4]. Another systematic literature review, conducted in 2010, revealed that the annual economic burden of UC was estimated to be between €12.5 and €29.1 billion in Europe and between $8.1 and $14.9 billion in the United States [Citation5]. A European epidemiology trial including 1,367 IBD patients from 31 centres also showed the total expenditure for the cohort equalled €5,408,174 (investigations: €2,042,990 (38%), surgery: €1,427,648 (26%), biologicals: €781,089 (14%), standard treatment: €1,156,520 (22%)) the first year after diagnosis [Citation6].

The objective of this study was to estimate the average 5-year societal costs attributable to incident CD or UC patients in Denmark. The study explored costs related to primary and secondary health care, prescription medicine, municipality provided home care services, and production loss.

Materials and methods

A cost-of-illness study applying a societal perspective was conducted using the national registers in Denmark. An incidence-based approach was applied to estimate the costs attributable to incident CD and UC patients diagnosed between years 2003 and 2015.

Register data sources

Data from years 2002–2016 on costs for the population incident in 2003–2015 was retrieved from several national registries that include the entire population. Using the Danish National Patient Registry (NPR), information on all admissions and outpatient visits to hospitals, and diagnosis codes according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) were retrieved [Citation7]. Information on primary health care services were obtained from the National Health Insurance Service Registry (NHSR) [Citation8]. Both registries are considered to be exhaustive because they are linked to the reimbursement and payment systems. Data on all prescription drugs sold in community pharmacies applying the international therapeutic chemical classification system (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical) was retrieved from the Registry of Medical Product Statistics [Citation9]. Using the Danish Longitudinal Database on Employment (the DREAM database), information on weekly labour market related public transfer payments for all citizens was obtained. Lastly, data on home care was extracted from Statistics Denmark, between the years of 2008–2016 due to data availability. The Danish Civil Registration System (CRS) which includes all citizens and residents with a civil personal registration number was used for an identity-secure linkage between the national registries at an individual level [Citation7]. As the private healthcare system constitutes for less than 1% of all the healthcare provided in Denmark, only residents treated within the public healthcare system were included.

Selection criteria

The following selection criteria was applied: (1) Individuals above age 18, with at least two hospital contacts (admission, outpatient or emergency room visit) collected from the NPR, in the period 2003–2015, with a primary or secondary diagnosis of CD or UC using the ICD-10 codes K50 and K51 and at least one of the registrations defined as the primary diagnosis; (2) Patients with no hospital contacts related to CD or UC during years 1994–2002 (wash-out period); (3) Incidence date was defined as the first hospital contact—admission, outpatient or emergency room visit—with CD or UC during years 2003–2015; (4) Patients diagnosed with UC followed by a CD diagnosis were categorized as diagnosed with CD.

For each identified case, one control was randomly selected from the population registry and matched at January 1st in the year of IBD diagnosis on age and gender. To be considered a matched control, the control had to be alive at day of disease diagnosis. Patients and controls were censored (e.g., excluded) at death and the end of follow-up (end of 2016). In the year of death or end of follow-up, the individual was included with a weight corresponding to the fraction of the year data were available for them.

Costs

Direct costs related to health care services, prescription medication, and home care services were included. Indirect costs of production loss were also included. Additionally, telephone consultations and any tests ordered and their resulting costs have also been included, whenever registered in the patient file.

Health care service costs were comprised of both primary and secondary services. Primary sector costs included private practice health care professionals, prescription medicine and those related to municipality provided home care services. Regarding prescription medicine, the market price including both patient co-payment and public reimbursement were analysed (pharmacy selling prices, incl. VAT). Home care costs were estimated as the allocated hours of nursing and practical services multiplied by hourly wages for social and health care workers in private homes [Citation10]. Data on the estimated home care costs is only available from 2008 and onwards. Costs of admissions, outpatient and emergency visits [applying the Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) and the Danish ambulatory grouping systems (DAGS) charges] were included as secondary health care services.

Using the DREAM database, yearly employment rates were estimated. Production values were then estimated by multiplying the yearly employment rate, with gender specific gross average yearly wages, adjusted for the number of effective weekly working hours among men and women [Citation11,Citation12]. Only cases and controls between 18 and 65 in a given year were included in the estimation of production values, as they are considered to constitute the Danish work force.

Primary sector healthcare costs, which include the gross fee healthcare professionals receive at each contact, were collected from the NHSR. Secondary healthcare costs, which includes hospital admission and outpatient costs (DRG/DAGS charges), were collected from the NPR. Costs of prescription medicine (e.g., the pharmacy selling price) were collected from the Register of Medicinal Product Statistics.

All costs were adjusted to the 2016 price level. The charges in the NHSR, DAGS and DRG were estimated using the combined price and wage index for healthcare services by the Danish Regions [Citation13]. Prescription medicine prices were not inflated as they fluctuate, making price indices difficult to interpret. In 2016, the annual average labour productivity value for men was €72,411 and €54,778 for women. In the present study all costs are reported in Euros with the exchange rate: €1 = DKK 7.5.

Statistical analyses

The annual incidence rates for UC and CD are presented as the incidence rates per 100,000 person years. Information on the size of the population for each year was obtained from Statistics Denmark.

The 5-year societal costs of CD and UC were estimated on the individual-level as both total and attributable costs. All costs were reported separately: primary sector, outpatient, hospital admission, prescription medicine, production loss, and home care costs. Total costs were estimated as the costs in year t after diagnosis, minus the costs in the baseline year (e.g., the year before the incidence date). A Student’s t-test was then applied to determine whether the total costs for cases are significantly different from those for controls. Attributable costs were estimated by applying a difference-in-difference approach, where the total costs among individuals in both control groups were subtracted from the total costs among patients with CD and UC, respectively.

To explore the consequence of diagnostic delay of IBD, a sensitivity analysis was performed. The fourth year prior to diagnosis was set as the baseline for this, thus including only patients with incidence between 2006 and 2015 in the analyses. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) on Statistics Denmark’s research computers via a remote server.

Ethical considerations

The study was register-based and complied with the regulations set up by the Danish Data Protection Agency (J. nr. 2014-54-0664). Only anonymized data in aggregated form was presented with no active participation/contact with the research subjects. Results including less than five individuals are reported as <5 to ensure anonymity of the individuals.

Results

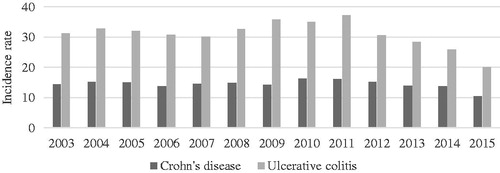

A total of 10,302 incident patients with CD and 22,144 with UC were identified during the period 2003–2015. The incidence rate of CD is approximately 14 per 100,000 person years, while the incidence rate of UC is more than twice as high, approximately 31 per 100,000 person years (). However, the incidence rates of both CD and UC fluctuate during the study period, appearing to decrease in the later years.

Figure 1. Annual incidence rates of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Denmark per 100,000 person years, 2003–2015.

The study population consisted of 9,019 incident CD patients and 20,913 incident UC patients, and an equal number of controls.

The average total costs, per patient, the first 5 years after diagnosis are presented in . In general, the average total costs are highest the first year after diagnosis and then decrease to approximately half in the following 4 years. This applies to both CD and UC patients. In the first year after diagnosis, the average total costs were €12,855 per CD patient and €6,728 per UC patient. In both patient populations, hospital admission costs and production loss were the main cost drivers the first year after diagnosis (CD: 37 and 31%; UC: 31 and 37%, respectively). In the CD population, total costs of hospital admissions were only significantly different the first two years after diagnosis.

Table 1. Average total costs per patient the first 5 years after diagnosis among incident patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis from 2003 to 2015, Euros 2016-prices.

The average attributable costs per CD patient were €12,919 the first year after diagnosis, and subsequently decreased to €5,276, €4,551, €4,191, and €4,671 the following 4 years after diagnosis, respectively (). Hospital admission costs accounted for 36% of the attributable costs the first year after diagnosis, whereas outpatient costs accounted for 29%, and production loss accounted for 34%. The attributable costs related to prescription medicine and home care were low, while those related to the primary sector were negative. This implied that the demand for primary sector health care services are lower after diagnosis for CD patients, compared to their controls.

Table 2. Average attributable costs per patient the first 5 years after diagnosis among incident patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis from 2003 to 2015, Euros 2016-prices.

The average attributable costs per UC patient were €6,501 the first year after diagnosis, decreasing every year after to €2,097, €1,746, €1,356, and €789 the following 4 years after diagnosis, respectively (). Costs of prescription medicine, home care, and primary sector only accounted for a small amount of the total attributable costs the first year after diagnosis. Outpatient costs accounted for 25% the first year after diagnosis, while hospital admission costs accounted for 31% and production loss 38%. In the following years, production loss accounted for up to 89% of the costs attributable to UC. For the CD population, production loss did also exceed all other costs in the third year after diagnosis.

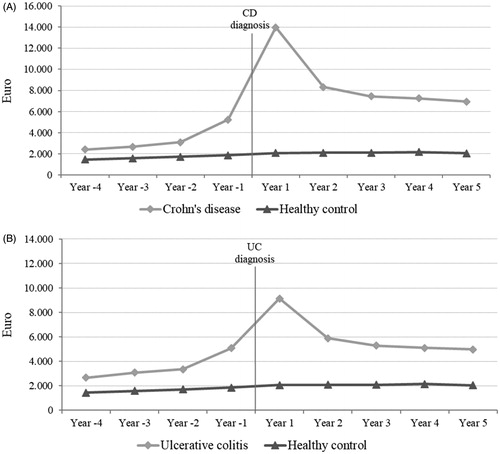

In , the average actual health care costs, per patient, from 4 years before diagnosis to 5 years after diagnosis are presented for both CD and UC patients. In the years before diagnosis, the average actual health care costs increase in both populations more than their corresponding controls. The sensitivity analysis showed that the total attributable costs were higher than the average attributable costs, and .

Figure 2. Average actual health care costs per person among (A) incident patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) from 2003 to 2015 and matched controls and (B) incident patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) from 2003 to 2015 and matched controls, Euros 2016-prices. All year’s show significant total cost differences between disease and healthy control (p < .05).

Table 3. Sensitivity analysis of average attributable costs per patient the first 5 years after diagnosis applying the fourth year before diagnosis as the baseline year, among incident patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis from 2006 to 2015, Euros 2016-prices.

Discussion

This study provides estimates of the average 5-year societal costs attributable to incident CD and UC patients in Denmark. The average attributable costs were highest the first year after diagnosis (€12,919 per CD patient and €6,501 per UC patient). Hospital admission costs and production loss were found to be the main cost drivers, while production loss exceeded all other costs in the third year after diagnosis in both populations. A sensitivity analysis applying the fourth year before diagnosis as the baseline year suggests that the attributable cost estimates presented in this study are conservative. Analyses on costs before the diagnosis with CD or UC are also investigated by our group and published in a separate article [Citation14].

Two recently published studies present estimates of incidence rates for both CD and UC in Denmark [Citation15,Citation16]. Lophaven et al. [Citation15] reported an incidence rate for CD of 9.1 per 100,000 person years between 2010 and 2013 and an incidence rate of 18.6 per 100,000 person years for UC during the same period. Nørgård et al. [Citation16] found a CD incidence rate of 9.5 and 8.8 per 100,000 person years for men and women, respectively, in 2012. Additionally, they report a UC incidence rate of 23.5 and 22.4 per 100,000 person years for men and women, respectively, in 2011. Thus, the incidence rates estimated in this study are slightly higher than the estimates from previous studies [Citation15,Citation16]. This is due to differences in selection criteria to identify incident CD and UC patients.

Due to differences in methodology, study design, population characteristics, time horizon, included costs and thereby the chosen perspective of the analyses, it is somewhat difficult to synthesize and compare the results of the present study with cost estimates identified in the literature. In the review by Yu et al. [Citation4], the direct medical costs per CD patient in western countries (excl. the United States) ranged from €2,898 to €6,960 (2006-prices) per year. For comparison, the average attributable health care costs (excl. production loss) in this study were estimated to be €8,587 in the first year after diagnosis, decreasing to below €2,000 in the fifth year after diagnosis for CD patients. In a review by Cohen et al. [Citation5], the direct medical costs per UC patient in western countries (excl. the United States) ranged from €8,949 to €10,395 (2006-prices) per year. In our study, the average attributable health care costs (excl. production loss) were estimated to be €4,056 in the first year after diagnosis, decreasing to below €500 in the fifth year after diagnosis for UC patients. Thus, the health care cost estimates in the present study are overall in line with cost estimates from the identified literature, however in the low end for UC patients. Similar to other studies, our results show that hospital admission and indirect costs dominant cost components [Citation4,Citation5]. Further, we found that production loss exceeded all other cost components in the third year after diagnosis in both the CD and UC populations.

A recent study of >13,000 Danish psoriasis patients, highlights the impact of health inequity from a patient perspective and the significant socioeconomic impact of psoriasis to the society, in agreement with this study. For psoriasis, the healthcare costs are approximately double compared to healthy controls in the years after diagnosis, comparable to the UC cohort, while the costs for the CD cohort are at least three times as high [Citation17].

This study has several strengths. First, using national registers helped prevent selection and information bias, as all Danish residents are included, the data is prospectively collected, and the quality of data is generally considered to be high. This also means that the generalizability of the results is high, as the study covers all incident cases of CD and UC in Denmark between years 2003 and 2015. A second strength is the large study population, that reduces the risk of random variation in the cost estimates of this study. Another strength is the application of a broad societal perspective in which home care, loss of production and health care costs were included.

This study also has some limitations. The study relies on registry collected costs, meaning that e.g., the cost of short-term sick leave, transportation time related to consultations, non-prescription drugs and costs of informal care provided by friends and family were not included, as this data is not available in the registries. Moreover, it is important to be aware that cost data rarely are normally distributed. Furthermore, there is a risk of misclassification, to identify CD and UC patients, as we relied on the accuracy of the ICD-10 coding in the NPR. The reliability and validity of the diagnosis registration in the NPR has been assessed to be good, however there have not been any studies that explicitly validate the registration of CD and UC diagnosis codes [Citation18–20]. The study aimed to prevent the potential of confounding by direct matching on age and gender, however as in all observational studies without random allocation to the exposure groups, e.g., individuals with and without IBD in this study, unmeasured confounding may still affect the validity.

In this study, a decreasing incidence of CD and UC was observed in the later years. This may be related to the selection criteria of two or more contacts regarding the disease. Comparing patients diagnosed earlier to patients with their first contact at the end of the study period, those diagnosed later have a smaller chance of fulfilling this criterion. Thus, the incidence in the later years is probably underestimated, contrasting with the increase found by Lophaven et al. [Citation15].

In this study, we were not able to include information on emigrations, which would also have been the end of follow up for a case or control.

In this study, we found that the societal costs attributable to CD and UC are substantial, especially in the first year after diagnosis. Hospital admission costs and production loss were found to be the main cost drivers. In conclusion, receiving a diagnosis of CD or UC significantly impacts the healthcare costs in Denmark. These patients do not only suffer from a poor quality of life and disease symptoms, but also production loss with societal impact, regarding their ability to secure employment and income. The findings of this study suggest future studies should focus on early diagnosis and appropriate treatment to reduce the socioeconomic impact of IBD in the society.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Disclosure statement

Data collection was carried out by Incentive, with financial support from the funder. The funder provided support in the form of salaries for authors KV, SA, AB and CW. TRJ is a former employee of Janssen Pharmaceuticals. SS and AN are paid employees of Incentive. NQ and PM have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:720–727.

- Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, et al. Crohn’s disease. Lancet Lond Engl. 2017;389:1741–1755.

- Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2017;389:1756–1770.

- Yu AP, Cabanilla LA, Wu EQ, et al. The costs of Crohn’s disease in the United States and other Western countries: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:319–328.

- Cohen RD, Yu AP, Wu EQ, et al. Systematic review: the costs of ulcerative colitis in Western countries. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:693–707.

- Burisch J, Vardi H, Pedersen N, et al. Costs and resource utilization for diagnosis and treatment during the initial year in a European inflammatory bowel disease inception cohort: an ECCO-EpiCom Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:121–131.

- Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:30–33.

- Andersen JS, Olivarius NDF, Krasnik A. The Danish National Health Service Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:34–37.

- Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:38–41.

- Statistics Denmark. Statistics database, Table LONS20, work function 5322. Available from: http://www.statistikbanken.dk/10328

- Statistics Denmark. Statistics database, Table SAO01. Available from: http://www.statistikbanken.dk/sao01

- Statistics Denmark. Statistics database, Table AKU502. Available from: http://www.statistikbanken.dk/aku502

- Danish Regions. Financial guide; 2017. Available from: https://www.regioner.dk/aftaler-og-oekonomi/oekonomisk-vejledning/oekonomisk-vejledning-2017

- Vadstrup K, et al. Cost burden of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the 10-year period before diagnosis-A Danish Register-Based Study from 2003-2015. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019. DOI:10.1093/ibd/izz265

- Lophaven SN, Lynge E, Burisch J. The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Denmark 1980-2013: a nationwide cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:961–972.

- Nørgård BM, Nielsen J, Fonager K, et al. The incidence of ulcerative colitis (1995-2011) and Crohn’s disease (1995-2012) - based on nationwide Danish registry data. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1274–1280.

- Thomsen SF, Skov L, Dodge R, et al. Socioeconomic costs and health inequalities from psoriasis: a cohort study. Dermatology. 2019;235:372–379.

- Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, et al. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449–490.

- Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, et al. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:12–16.

- Kruse M, Christiansen T. Register-based studies of healthcare costs. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:206–209.