Abstract

Objective: Randomized controlled trials have shown the effectiveness of Adalimumab in ulcerative colitis. However, real-life data is scarce. We aimed to assess the effectiveness and predictive factors of effectiveness in a large Swedish cohort.

Methods: Retrospective capture of data from local registries at five Swedish IBD centers. Clinical response and remission rates were assessed at three months after starting adalimumab treatment and patients were followed until colectomy or need for another biological. Bio-naive patients were compared to bio experienced patients. Factors associated with short term responses were assessed using logistic regression model. Failure on drug was assessed using a Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Results: 118 patients (59 males, 59 females) with median age 34.4 years (IQR 27.0–51.4) were included. Median disease duration was 4.3 years (IQR 2.0–9.0) and follow-up 1.27 years (IQR 0.33–4.1). A clinical corticosteroid-free remission was achieved by 38/118 (32.2%) and response by 91/118 (77%) after three months. CRP >3 mg/l at baseline was predictive of short-term failure to reach corticosteroid-free remission. Factors associated with survival on the drug were male gender, CRP <3 mg/l and absence of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Patients >42 years of age at diagnosis were more likely to respond to adalimumab and remain on treatment compared to patients <20 years.

Conclusions: An elevated CRP-level, primary sclerosing cholangitis and female gender were predictors of treatment failure. In contrast older age at diagnosis was a predictor of short-term clinical response and drug survival. Prior infliximab failure, regardless of cause, did not influence the outcome of adalimumab treatment.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis is a chronic, idiopathic disease-causing inflammation restricted to the colonic mucosa [Citation1]. The pathogenesis is not fully elucidated, but there is evidence of an inappropriate immune response in the gut mucosa targeted at commensal organisms in the gut in predisposed individuals [Citation1]. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) seems to be an important proinflammatory cytokine involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease [Citation2]. Infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody to TNF, has been shown to be effective in patients with ulcerative colitis for induction and maintenance of clinical remission, as well as endoscopic healing [Citation3]. Due to infliximab’s immunogenicity, combination therapy with azathioprine has proven to be more effective compared to either drug alone [Citation4,Citation5]. There are concerns regarding the risk of developing malignancies due to long-term treatment with azathioprine [Citation6–8]. Treatment with azathioprine and especially the combination with an anti-TNF α drug, has also been associated with the rare, fatal disease of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma [Citation9,Citation10]. Adalimumab, a fully humanized recombinant monoclonal antibody against TNF α has demonstrated superior efficacy compared to placebo in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Clinical remission in the ULTRA 1 trial was achieved by 18.5% versus 9.2% in the placebo group [Citation11]. The optimal induction dose of adalimumab has been debated as well as the potential benefit of combination therapy with immunomodulators. Real-life studies on adalimumab in ulcerative colitis are scarce and comprise mostly small numbers of patients. The results diverge in regard to initial remission and response rates as well as predictors of outcome. In the present study, we evaluated the short (three months) and long-term effectiveness and safety of adalimumab. Secondly, we assessed the outcome of adalimumab treatment in relation to previous infliximab experience. Thirdly, we compared the outcome in relation to reason for failure in the infliximab experienced group, and finally, we examined potential predictors of failure both short and long-term.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective study, conducted at three academic and two district hospitals. Patients included, started adalimumab treatment between 2007 and 2015. Patients were identified through local registers. All patients of at least 18 years of age with a confirmed diagnosis of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, and with adalimumab therapy, were included. Patients with Crohn’s disease or prior surgery involving the colon were excluded. Data regarding age, gender, disease duration, extent and laboratory values (hemoglobin, albumin, C-reactive protein (CRP), and fecal Calprotectin), were collected at baseline using a study-specific case record form. Data regarding concomitant medication were collected, including 5-aminosalicylic acid, corticosteroids and immunomodulators. The induction dose of adalimumab as well as need for dose-escalation was recorded. The diagnosis of ulcerative colitis was based on established conventional diagnostic criteria [Citation12]. All patients had a documented colonoscopy and gastrointestinal infections had been ruled out. Extent of disease was defined according to the Montreal classification [Citation13]. Safety data regarding severe adverse events (SAE) were documented. All patients were followed until failure on drug or time for observation.

Outcome measures

The following outcome measures were studied: (i) clinical corticosteroid-free remission and (ii) clinical response at three months. (iii) failure on adalimumab. Clinical corticosteroid-free remission was defined as the absence of corticosteroids, diarrhea and blood in stools as judged by the physician’s global assessment. Clinical response was defined as at least marked clinical improvement of symptoms (less diarrhea, abdominal pain and bloody stools). Adalimumab failure was defined as discontinuation of adalimumab due to non-response, loss of response or intolerance as well as other side effects.

Statistics

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies and differences between groups were compared using the chi-square test or Mann–Whitney’s test when appropriate. Continuous variables are presented as median with interquartile range (IQR). Kaplan–Meier plots were used to illustrate time remaining on adalimumab. All demographic and clinical variables were analyzed as categorical. The following covariates were included in the analysis and processed as follows: Age at diagnosis, as well as age at adalimumab start and disease duration were divided into quartiles when analyzed. Disease extension was divided into proctitis, left sided and extensive colitis according to the Montreal classification. Hemoglobin, CRP and F-calprotectin were divided by the median. Concomitant medication with corticosteroids, azathioprine/purinethol, aminosalicylates and induction dose of adalimumab were assessed as dichotomous variables. All variables were tested one by one in a univariate model, and then analyzed in a logistic regression model in regard to clinical response and corticosteroid-free remission at three months. A Cox regression model was used to evaluate the same variables in regard to failure on drug. Kaplan-Maier plots were constructed to compare bio-naïve versus infliximab experienced patients; non-responders to infliximab versus patients with loss of response; and patients having undergone dose escalation versus no dose escalation on adalimumab. Differences between groups were calculated using Log-rank test. A statistical significance was set at 95% CI (p < .05). Statistical calculations were performed using SAS, version 9,4 (Cary, NC, USA). Kaplan-Meier plots were made using SPSS software (version 24, released 2016; IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Research Committee, Lund. Data were collected individually and all patients were anonymized before entering the analysis of data.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are presented in . Data were collected retrospectively from 118 ulcerative colitis patients treated with adalimumab. Median age at first adalimumab injection was 34.4 years (IQR 27.0–51.4). Of the 118 patients, 40/118 (33.9%) were bio-naïve. The remaining 78 (66.1%) patients had previously been treated with infliximab. All but 5/78 (6.4%) patients had failed infliximab treatment. The remaining five patients were switched to adalimumab for reasons of patient convenience. The reasons for failure on infliximab were loss of response in 28/73 (38.4%) patients, intolerance in 20/73 (27.4%) and non-response in 12/73 (16.4%), the remaining 13/73 (17.8%) were stopped for various other reasons. At start of adalimumab treatment, 34/118 (28.8%) patients were on concomitant thiopurine treatment and 65/118 (55.1%) patients were on oral corticosteroids. Demographic data and clinical characteristics of the bio-naïve and the infliximab-exposed groups are presented in . There were no significant differences between the two groups except for concomitant corticosteroid treatment, which was more common in the bio-naïve group (30/40 (75%) versus 35/78 (44.9%) p = .002). The median disease duration at inclusion was 5.1 years (IQR 3.0–9.2) for the previously infliximab treated patients compared to 2.0 years (IQR 1.3–7.5) in the bio-naïve patients but this was not statistically significant. Seven patients had concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics in 118 patients receiving adalimumab due to ulcerative colitis (at inclusion).

Clinical response and corticosteroid-free remission rate at three months

Corticosteroid-free clinical remission after three months was achieved by 38/118 (32.2%). Remission rates comparing bio-naïve patients 14/40 (35%) and infliximab-experienced patients 24/78 (31%) did not differ (p = .67). A clinical response at three months was noted in 91/118 (77%) of the patients. Although a numerically higher response was seen in bio-naïve patients 34/40 (85%) than in infliximab-exposed patients 57/78 (73%), this was not statistically significant (p = .14).

Factors predicting clinical corticosteroid-free remission and response at three months

Factors predicting corticosteroid-free clinical remission after three months of adalimumab treatment were analyzed in a logistic regression model. A CRP >3 mg/L turned out to be the only statistically significant factor in the univariate analysis and a negative predictor of clinical steroid free remission at three months (OR 0.19, 95% CI = 0.07–0.50, p = .0008). In the multivariate analysis, CRP >3 mg/L remained as a significant negative predictor for short-term steroid free remission (OR 0.06, 95% CI = 0.01–0.28, p = .0005), together with a hemoglobin level >130 g/L (OR 0.22, 95% CI = 0.05–0.88, p = .032) and concomitant aminosalicylate medication (OR 0.30, 95% CI = 0.10–0.96, p = .043) . A logistic regression model concerning response at three months revealed no significant variables in the univariate analysis. However, in the multivariate analysis, older age at diagnosis (>42 years) was a predictor of achieving response compared to age less than 20 years (OR 14.17, 95% CI = 2.96–>999.9, p = .0085). In addition, a CRP >3 mg/L was a negative predictor of achieving response (OR 0.247, 95% CI = 0.06–0.95, p = .0425) .

Table 2. Predictors of steroid free remission at 3 months after initiation of adalimumab in a cohort of 118 patients with ulcerative colitis.

Table 3. Predictors of response at 3 months after initiation of adalimumab in a cohort of 118 patients with ulcerative colitis.

Clinical corticosteroid-free remission and response in infliximab exposed patients in relation to reason for failure on infliximab

Of non-responders to infliximab, 8/12 (67%) achieved response and the corresponding figure for patients with loss of response was 19/28 (68%). Adding patients with intolerance to infliximab (n = 20) to the group with loss of response, resulted in a response rate of 35/48 (73%).

The corresponding figures for clinical corticosteroid free remission were 4/12 (33%) for non-responders to infliximab, 8/28 (29%) for those with loss of response and 13/48 (27%) for the group of loss of response and intolerance. No significant differences concerning response or corticosteroid-free remission were found.

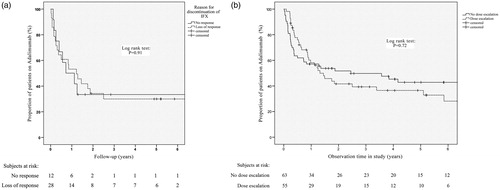

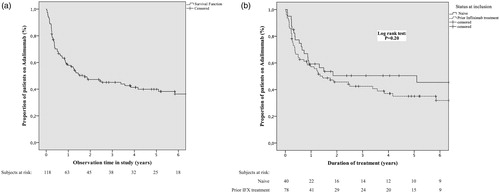

Factors predicting failure on drug

Overall, 67/118 (57%) failed on adalimumab after a median observation time of 1.27 years (IQR 0.33–4.09), bio-naïve 20/40 (50%) median 1.41 years (IQR 0.42–4.93) and infliximab experienced 47/78 (60.3%), median 1.24 years (IQR 0.27–4.05) respectively. A non-significant difference was noted between the groups in the multivariate analysis . shows a Kaplan-Meier survival curve for remaining on adalimumab. A Cox proportional hazard model was applied to determine factors predictive of failure. In the univariate analysis only, comorbidity with PSC was found to be a significant predictor of failure on adalimumab (HR 2.35, 95% CI = 1.07–5.18, p = .034). In the subsequent multivariate analysis, three factors were significant predictors of drug failure: Female gender (HR 2.50, 95% CI = 1.38–6.27, p = .0051), concomitant PSC (HR 5.91, 95% CI = 1.78–19.65, p = .0037) and a CRP >3 mg/L (HR 3.23, 95% CI = 1.55–6.74, p = .0018). In contrast older age (>42 years) at diagnosis was associated with a higher chance of remaining on drug (HR 0.165, 95% CI = 0.30–0.92, p = .0394) .

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier survival curve for remaining on adalimumab without failure (a) in the whole cohort of 118 patients and (b) in bio-naïve compared to infliximab experienced patients. p-value obtained from log-rank test.

Table 4. Predictors of failure on adalimumab in a cohort of 118 patients with ulcerative colitis (at inclusion).

Drug survival on adalimumab in relation to previous infliximab exposure and reason for failure

A Kaplan–Meier survival plot was generated, comparing failure on drug among bio-naïve and infliximab-experienced patients. No significant difference could be demonstrated (log-rank: p = .20) . The reason for failure on infliximab in relation to adalimumab treatment outcome was separately studied by using Kaplan–Meyer survival plots comparing patients with primary non-response to infliximab (12 patients) to those with a secondary loss of response (28 patients). No significant differences were found between the groups (log-rank test: p = .91) . A further analysis was done comparing the 12 non-responders to patients with loss of response combined with those who failed infliximab due to intolerance (48 patients). Again, no significant difference could be demonstrated (log-rank test: p = .75).

Outcome after dose-escalation

Survival analysis was performed comparing the group with dose-escalation to those who were not. Overall 55/118 (46.6%) patients were dose escalated. No significant difference was found between the two groups in regard to drug survival (log-rank test: p = .72) . A second analysis was performed on the 55 dose-escalated patients, comparing failure on drug among bio-naïve 14/22 (63.6%) and infliximab experienced 20/33 (60.6%) patients. Again, no statistically significant difference was found (log-rank test: p = .82).

Safety

Overall, adverse events leading to discontinuation of adalimumab treatment, were recorded in 17/118 (14.4%) patients. Two patients were diagnosed with malignancies (one gastric intestinal stromal cancer and one lung cancer). Five patients experienced various infections (single cases of Listeria sepsis, meningoencephalitis, osteitis, CMV-colitis and local infection at the injection site). Four patients experienced skin rash, three patients myalgia, one pancreatitis, one psoriasis and one patient had an unclear pulmonary lesion. Of the eleven patients with prior infliximab treatment and an adverse event on adalimumab, six discontinued infliximab due to hypersensitivity reactions and five experienced loss of response. The median time until an adverse event on adalimumab was 0.62 years (IQR 0.25–2.16). The overall one-year rate of adverse events one year was 8.5%.

Discussion

There is a lack of large real-life studies on the outcome and predictors of outcome of adalimumab treatment in ulcerative colitis. Except for a Spanish study by Iborra et al. on 263 patients [Citation14], there is no previous study with more than 90 patients [Citation15–18] and most studies comprise fewer than 50 patients [Citation19–24]. We here report a Swedish multicenter real-life cohort study of 118 patients. Approximately one third 40/118, were naïve to biologics and two-thirds were previously treated with infliximab. An overall high short-term clinical response rate of 91/118 (77%) was noted. The bio-naïve group had an even higher response rate of 34/40 (85%) compared to the previously infliximab exposed group 57/78 (73%), although not statistically significant. Moreover, a steroid-free clinical remission was achieved by almost a third of the patients (32.2%). In other real-life studies, clinical response rates have varied from 29% to 80% and clinical remission rates from 26 to 50% [Citation14–17,Citation20,Citation21,Citation23,Citation24]. It is difficult to compare the results from individual studies due to differences in design, selection of patients and study endpoints. We did not analyze colectomy as an endpoint in this study because in the time period studied primary adalimumab failures generally received another biologic while previously infliximab experienced patients were more likely to be colectomized after adalimumab failure.

We did not find higher clinical response rates or longer drug survival in the bio-naïve group. This is in line with other real-life studies comparing outcome of adalimumab treatment in bio-naive vs infliximab experienced patients [Citation14,Citation17,Citation19,Citation20,Citation25,Citation26]. In contrast, the randomized ULTRA 2 clinical trial, demonstrated that significantly more anti-TNF naive patients achieved clinical remission at week 8 (21.3 versus 11%; p = .017) and at week 52 (22.0% vs. 12,4%; p = .029) [Citation26].

There is limited data on the outcome of a second anti-TNF treatment in relation to the reason for failure of the first anti-TNF agent. We did not find any difference concerning short-term response or remission rates between infliximab non-responders and those who lost response over time, nor did we see any differences in drug survival. The lack of difference in drug survival may be confounded by the fact that secondary adalimumab users remained longer on the drug because colectomy often being the only option when failing, while primary adalimumab users could be switched to infliximab. Vedolizumab, introduced in 2014, was not available for most of the patients in the study as data was collected 2007–2015. The short term data are in contrast to Baert et al. who found short term response to be 36% in infliximab non-responders, compared to 83% in patients discontinuing infliximab for other reasons than non-response. The difference remained after one year (27 versus 58%) [Citation16]. In a study by Garcia-Bosch et al. 33.3% of the non-responders to infliximab responded to adalimumab, while 90% of the patients with previous remission on infliximab achieved response at 12 weeks [Citation20]. However, our result indicates that adalimumab may be tried irrespective of the reason for failure of the first anti-TNF.

Concomitant medication with immunomodulators did not influence the short-term outcome or drug survival in our cohort. The impact or need for combination therapy with adalimumab and immunomodulators has been debated and the results are diverging. Zhang et al. presented a meta-analysis including three randomized clinical trials indicating combination therapy to be superior to adalimumab monotherapy [Citation27]. However, exploratory post hoc analyses of the ULTRA 1 and ULTRA 2 studies by Colombel et al. did not show any advantage with combination therapy [Citation28]. Hence, this issue needs further investigation.

Patients with concomitant aminosalicylate treatment at adalimumab start had a significantly lower rate of clinical steroid-free remission at three months. Only 64,4% of the patients in our cohort were on concomitant aminosalicylate treatment, although it is an established baseline treatment in mild to moderate ulcerative colitis [Citation29]. A similar finding was observed in the ULTRA 1 study [Citation11]. As in our cohort, the number of patients with concomitant aminosalicylate was low, around 80%. Some of the larger real-life studies examining the clinical outcome of adalimumab treatment in patients with ulcerative colitis did not include aminosalicylates as a predictor of outcome [Citation14,Citation25]. Thus, this is also an issue that needs further investigation.

We found the presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis to be a significant independent predictor of failure on drug. This finding is not previously described in the literature. However, due to the small number of patients, the finding should be interpreted with precaution. Female gender was also found to be associated with failure on drug. This is supported by Gonczi et al. [Citation30] who found loss of response to be more common in females, both in ulcerative colitis and in Crohn´s disease.

An elevated CRP (>3 mg/L) was an independent predictor of failure on drug as well as of failure to achieve clinical response or clinical corticosteroid free remission. This observation is shared by others [Citation11,Citation14]. A higher CRP may imply a heavier inflammatory burden which in turn may require higher doses of adalimumab to induce remission. We did not include F-calprotectin in the multivariate analysis due to the small sample size.

Finally, a higher age at diagnosis (>42 years) was associated with a favorable short-term response and drug survival. Previous results on this subject are diverging. Ferrante et al. found a positive correlation between younger age and response to infliximab [Citation31]. In contrast, Jakobovits et al. showed that younger age correlated to an increased risk of surgery in refractory ulcerative colitis [Citation32].

Our study has several limitations. The retrospective design may limit the validity of data due to potential selection bias. For example, the heterogenous use of concomitant medication may influence outcome. In addition, the assessment of therapeutic efficacy short-term was based on clinician’s assessment without disease activity indices, biomarkers or endoscopy. Drug monitoring was not routinely applied in the time period of data collection.

In spite of these shortcomings, the data presented may provide the clinician important information on the outcome of adalimumab treatment in patients with ulcerative colitis. In conclusion, short-term response and clinical remission rates were found to be high both in bio-naive and infliximab experienced patients. Higher age at diagnosis and a low CRP-level were predictive of a favorable course both short and long-term. In contrast, female gender and primary sclerosing cholangitis were predictors of failure. Finally, adalimumab may be considered as a treatment option in ulcerative colitis irrespective of the reason for prior failure on infliximab.

Disclosure statement

LA has received lecturing fees from Takeda, SA received Adv.board + lecture fee Takeda, Jansen, consultancy Hospira and AbbVie, EH has served as a speaker, a consultant, and/or an advisory board member for Abbvie, Merck, Sharp & Dohme (MSD), and Takeda. JM has served as a speaker, a consultant, and/or an advisory board member for AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, EuroDiagnostica, Ferring, Hospira, Janssen-Cilag, Merck, Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Otsuka, Pfizer, Sandoz, Takeda, Tillotts, and UCB Pharma. JM has received investigator-initiated study funding from AbbVie, Ferring, and Pfizer. SL has received fees as lecturer and advisory board member from AbbVie, as lecturer from Takeda and as principal investigator from MSD. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017;389(10080):1756–1770.

- Van Deventer SJ. Tumour necrosis factor and Crohn's disease. Gut. 1997;40(4):443–448.

- Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2462–2476.

- Armuzzi A, Pugliese D, Danese S, et al. Long-term combination therapy with infliximab plus azathioprine predicts sustained steroid-free clinical benefit in steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(8):1368–1374.

- Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Middleton S, et al. Combination therapy with infliximab and azathioprine is superior to monotherapy with either agent in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(2):392–400 e3.

- Kotlyar DS, Lewis JD, Beaugerie L, et al. Risk of lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(5):847–858.

- Long MD, Herfarth HH, Pipkin CA, et al. Increased risk for non-melanoma skin cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(3):268–274.

- Pasternak B, Svanstrom H, Schmiegelow K, et al. Use of azathioprine and the risk of cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;177(11):1296–1305.

- Parakkal D, Sifuentes H, Semer R, et al. Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in patients receiving TNF-a inhibitor therapy: expanding the groups at risk. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:1150–1156.

- Scott FI, Vajravelu RK, Bewtra M, et al. Original article: the benefit-to-risk balance of combining infliximab with azathioprine varies with age: a markov model. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(2):302–309.e11.

- Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Hommes DW, et al. Adalimumab for induction of clinical remission in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results of a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2011;60(6):780–787.

- Dignass A, Eliakim R, Magro F, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis Part 1: definitions and diagnosis. J Crohn's Colitis. 2012;6(10):965–990.

- Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 (Suppl A):5a–36a.

- Iborra M, Perez-Gisbert J, Bosca-Watts MM, Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU), et al. Effectiveness of adalimumab for the treatment of ulcerative colitis in clinical practice: comparison between anti-tumour necrosis factor-naive and non-naive patients. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(7):788–799.

- Armuzzi A, Biancone L, Daperno M, et al. Alimentary tract: adalimumab in active ulcerative colitis: a “real-life” observational study. Dige Liver Dis. 2013;45(9):738–743.

- Baert F, Vande Casteele N, Tops S, et al. Prior response to infliximab and early serum drug concentrations predict effects of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40(11–12):1324–1332.

- Balint A, Farkas K, Palatka K, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in ulcerative colitis refractory to conventional therapy in routine clinical practice. Eccojc. 2016;10:26–30.

- Hussey M, Mc Garrigle R, Kennedy U, et al. Long-term assessment of clinical response to adalimumab therapy in refractory ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(2):217–221.

- Afif W, Leighton JA, Hanauer SB, et al. Open-label study of adalimumab in patients with ulcerative colitis including those with prior loss of response or intolerance to infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(9):1302–1307.

- Garcia-Bosch O, Gisbert JP, Canas-Ventura A, et al. Observational study on the efficacy of adalimumab for the treatment of ulcerative colitis and predictors of outcome. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:717–722.

- Gies N, Kroeker KI, Wong K, et al. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with adalimumab or infliximab: long-term follow-up of a single-centre cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(4):522–528.

- McDermott E, Murphy S, Keegan D, et al. Efficacy of Adalimumab as a long term maintenance therapy in ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(2):150–153.

- Taxonera C, Estelles J, Fernandez-Blanco I, et al. Adalimumab induction and maintenance therapy for patients with ulcerative colitis previously treated with infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(3):340–348.

- Tursi A, Elisei W, Picchio M, et al. Effectiveness of adalimumab for ambulatory ulcerative colitis patients after failure of infliximab treatment: a first “real-life” experience in primary gastroenterology centers in Italy. Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27(4):369–373.

- Armuzzi A, Pugliese D, Nardone OM, et al. Management of difficult-to-treat patients with ulcerative colitis: focus on adalimumab. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:289–296.

- Sandborn WJ, van Assche G, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(2):257–265.e3.

- Zhang ZM, Li W, Jiang XL. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab in moderately to severely active cases of ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis of published placebo-controlled trials. Gut Liver. 2016;10(2):262–274.

- Colombel JF, Jharap B, Sandborn WJ, et al. Effects of concomitant immunomodulators on the pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety of adalimumab in patients with Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis who had failed conventional therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:50–62.

- Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(10):991–1030.

- Gonczi L, Kurti Z, Rutka M, et al. Drug persistence and need for dose intensification to adalimumab therapy; the importance of therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel diseases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17(1):97–97.

- Ferrante M, Vermeire S, Katsanos KH, et al. Predictors of early response to infliximab in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(2):123–128.

- Jakobovits SL, Jewell DP, Travis SP. Infliximab for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: outcomes in Oxford from 2000 to 2006. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25(9):1055–1060.