Abstract

Background: Geographical variations in the incidence and tumour stage distribution of oesophageal cancer in Sweden are not well characterised.

Methods: Using data from the Swedish Cancer Registry over 45 years (1972–2016), we compared the age-standardised incidence rates of oesophageal cancer by histological type across all seven national areas (in five-year periods) and 21 counties (in 15-year periods) in Sweden, and assessed the geographical distribution of tumour stage at diagnosis since 2004.

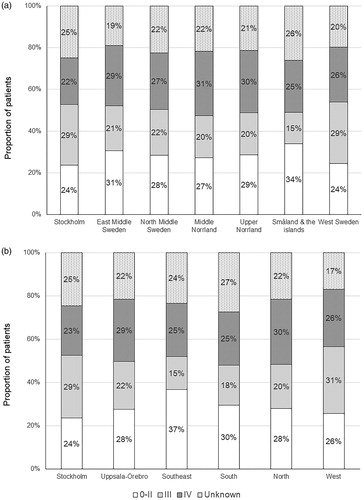

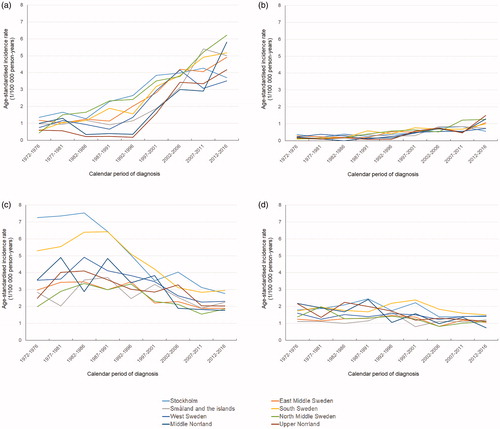

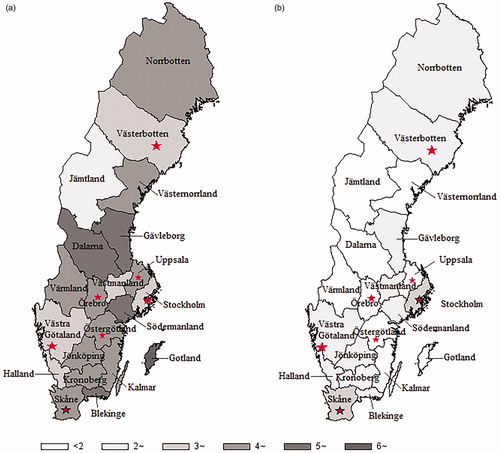

Results: The incidence rate of oesophageal adenocarcinoma increased in all national areas and counties and in both sexes over time, while the rate of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma decreased from the 1980s onwards. In the latest period (2012– 2016), the incidence rate of adenocarcinoma in men ranged from 3.5/100,000 person-years in West Sweden to 6.2/100,000 person-years in North Middle Sweden. At the county level, the rate of adenocarcinoma in men was lowest in Jämtland (2.7/100,000 person-years) and highest in Gotland (6.2/100 000 person-years) in 2002–2016. The incidence rates of both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in women were below 2/100,000 person-years in all national areas and counties in the latest calendar periods, i.e., 2012–2016 and 2002–2016, respectively. The proportion of patents with tumour stage IV ranged from 22% in Stockholm area to 31% in Middle Norrland, while at the healthcare region level it was lowest in Stockholm healthcare region (23%) and highest in North (30%) and Uppsala-Örebro (29%) healthcare regions.

Conclusion: There are considerable geographical variations in the incidence and tumour stage distribution of oesophageal cancer in Sweden.

Introduction

Oesophageal cancer is an aggressive malignancy with an overall five-year survival below 15% and lower in patients diagnosed at advanced tumour stages [Citation1]. Oesophageal cancer has two main histological types, i.e., adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. In Sweden, the incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma has rapidly increased during the past four decades, while the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma has steadily decreased over time [Citation2]. Substantial geographical variations in the incidence of oesophageal cancer have been noted in some countries [Citation3–Citation5], but any such variations in Sweden have not been well characterised. An earlier nationwide analysis of all deaths from oesophageal cancer in 1990–2007 in Sweden reported higher mortality rates of oesophageal cancer in more densely populated regions [Citation6]. Such observed geographical disparity remains to be explained, but could be due to differences in incidence, timing of diagnosis, treatment or other prognostic factors.

By using data from the nationwide complete Swedish Cancer Registry, we aimed to clarify potential geographical variations in the incidence of oesophageal cancer by histological type and calendar period in Sweden. We also aimed to assess possible differences in tumour stage at diagnosis (reflecting early or delayed diagnosis) across geographical regions in the country.

Materials and methods

Data sources

We extracted age- and sex-specific data on all incident cases of oesophageal cancer (International Classification of Diseases, 7th edition [ICD-7] code 150) in 1972–2016 in Sweden from the Swedish Cancer Registry by year of diagnosis, county of residence, and tumour histology. The Swedish Cancer Registry has a 98% nationwide coverage of oesophageal cancer [Citation7]. The well-established histology codes (WHO/HS/CANC/24.1) defined adenocarcinoma (code 096) and squamous cell carcinoma (code 146). Data on age-, sex- and county-specific population sizes were from the Swedish Registry of the Total Population, which is 100% complete.

Classification of geographical regions

The following three levels of geographical classification were used in this study: (1) the 21 counties (län in Swedish); (2) the seven Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) national areas, according to the standard by the European Union [Citation8] and (3) the six Swedish healthcare regions for cooperation in advanced or specialised medical care [Citation9]. The detailed grouping of counties into different NUTS national areas and healthcare regions is presented in . Because Halland county is part of both the West and South healthcare regions, this county was excluded from the analysis by healthcare region.

Table 1. Classification of geographical regions in Sweden.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the crude and age-standardised incidence rates of oesophageal cancer by sex and histological type for each NUTS national area in nine consecutive five-year calendar periods during the study period and for each county in three 15-year calendar periods (1972–1986, 1987–2001 and 2002–2016). The calculation of incidence rates by 15-year periods only, instead of five-year periods, at the county level was because of the limited number of cases in most individual counties. The age-standardised rates were calculated using the direct method with the Swedish population in the year 2000 as the reference.

We compared the distribution of tumour stage at diagnosis across the seven NUTS national areas and the six healthcare regions in patients diagnosed with oesophageal cancer from 2004 onwards, when tumour stage data were introduced in the Swedish Cancer Registry. The completeness and accuracy of tumour staging in the Swedish Cancer Registry have been estimated to be >98% [Citation10]. We calculated the number of cases and the corresponding percentage out of all cases by tumour stage for each NUTS national area and healthcare region. Tumour stage was categorised into stage 0–II, III, IV, or unknown, according to the seventh version of TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours by the Union for International Cancer Control [Citation11]. Chi square tests were used to compare the number of cases diagnosed at different tumour stages across geographical and healthcare regions.

All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Carry, NC). A two-sided p value below.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

During the 45-year study period, 5546 new cases of oesophageal adenocarcinoma (4513 [81%] males and 1033 [19%] females) and 9329 new cases of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (6157 [66%] males and 3172 [34%] females) were identified.

Geographical variation in incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma

The age-standardised incidence rate of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in men increased from <2 per 10,000 person-years in all NUTS national areas in 1972–1976 to a range between 3.5 (West Sweden) and 6.2 (North Middle Sweden) per 100,000 person-years in 2012–2016 (). At the county level, the rate of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in men ranged from 0.3–2.8 per 100,000 person-years in 1972–1986 (), while in 2002–2016 it was highest (6.2 per 100,000 person-years) in Gotland and lowest (2.7 per 100,000 person-years) in Jämtland ( and ). The rate of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in women also increased over time but remained <2 per 100,000 person-years in all NUTS national areas and all counties during the entire study period ( and ).

Figure 1. Age-standardised incidence rate of oesophageal cancer by sex and histological type for each national area in Sweden in 1972–2016. (a) adenocarcinoma in men; (b) adenocarcinoma in women; (c) squamous cell carcinoma in men; (d) squamous cell carcinoma in women.

Figure 2. County-specific age-standardised incidence rate (per 100,000 person-years) of (a) oesophageal adenocarcinoma and (b) oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in men in Sweden in 2002–2016. The stars indicate the locations of the specialised upper gastrointestinal oncology units.

Table 2. Crude and age-standardised incidence rates of oesophageal adenocarcinoma by sex and calendar period for each county in Sweden, 1/100,000 person-years.

Geographical variation in incidence of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma

The age-standardised incidence rate of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma decreased during the study period in both sexes and in all NUTS national areas and counties. The rate of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in men ranged from 2 (North Middle Sweden) to 7.3 (Stockholm area) per 100,000 person-years in 1972–1976, while it was <3 per 100,000 person-years in all NUTS national areas in 2012–2016 (). At the county level, the rate of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in men was highest in Stockholm county (7.4 per 100,000 person-years) and lowest in Värmland in 1972–1986 (1.9 per100,000 person-years; ), while it ranged from 1.6 (Jämtland) to 3.3 (Stockholm) per 100,000 person-years in 2002–2016 ( and ). The rate of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in women was <2 per 100,000 person-years in all NUTS national areas and counties during the latest periods, i.e., 2012–2016 and 2002–2016, respectively ( and ).

Table 3. Crude and age-standardised incidence rates of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma by sex and calendar period for each county in Sweden, 1/100,000 person-years.

Tumour stage

Variations in tumour stage at diagnosis were found across NUTS national areas and healthcare regions in 2004–2016 in Sweden (p < .05 for both). The proportion of patents diagnosed at stage IV was lowest in the Stockholm area (22%) and highest in Middle Norrland (31%) and Upper Norrland (30%; ). At the healthcare region level, the proportion was lowest in the Stockholm healthcare region (23%) and highest in North (30%) and Uppsala-Örebro (29%) healthcare regions ().

Discussion

This nationwide analysis of updated data through 2016 indicated distinct patterns of geographical variation in the incidence and tumour stage of oesophageal cancer by histological type in Sweden. The rate of oesophageal adenocarcinoma, particularly in men, varied substantially across geographical regions in recent years, while such disparities in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma decreased over time. Patients in certain geographical and healthcare regions were diagnosed at a more advanced stage than those in other regions.

Strengths of this study include the updated, complete and nationwide coverage of the Swedish Cancer Registry and the measurement of geographical variations at multiple levels. However, this study also has several limitations. First, we had no data on risk factors for oesophageal cancer from the patients, and thus, were unable to investigate how the observed disparities could be explained by known risk factors. Second, due to the limited incidence of oesophageal cancer and the population sizes by geographical region, particularly in individual counties, some estimates of incidence rates had relatively low precision. Third, we evaluated only geographical variations according to the patients place of residence at the time of cancer diagnosis and were not able to consider previous relocations, which might be limited.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and obesity are the two main established risk factors for oesophageal adenocarcinoma, while Helicobacter pylori infection decreases the risk [Citation1,Citation12]. The increasing incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in Sweden parallels the increasing prevalence of the two risk factors and the decreasing prevalence of H. pylori infection in the Scandinavian populations [Citation13–Citation15]. The higher incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in North Middle Sweden and Gotland county in recent years are consistent with the historically higher prevalence of overweight and obesity in these regions relative to other regions (Supplementary Figure 1) [Citation16]. However, there are no data available on the prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease by geographical region in Sweden.

Tobacco smoking and excess alcohol use are the two main risk factors for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Western populations. The observed decreasing incidence of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma reflects the historically decreasing prevalence of tobacco smoking in Sweden [Citation17], while the prevalence of alcohol use has been stable across successive birth cohorts (generations) in Sweden [Citation18]. The historically higher incidence of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in South Sweden and Stockholm may be partially explained a higher prevalence of tobacco smoking or alcohol consumption in these regions compared to other regions, although the disparities in the incidence of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma and smoking prevalence across regions did not correlate well [Citation16]. The higher prevalence of alcohol consumption in the south of Sweden that was noted previously [Citation19], might also explain the higher incidence of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma in these regions.

The observed disparities in tumour stage at diagnosis should be interpreted with caution, because the completeness and accuracy of the staging may not be entirely comparable across regions. The recorded tumour stage is dependent on the timing of the reporting to the registry by clinicians, whether the patients received surgical treatment (which allows pathological examination and provides more accurate staging) and use of neo-adjuvant therapy (which may have reduced the tumour size). Nevertheless, the comparison of the proportion of patients diagnosed at stage IV would be valid, as these patients generally do not undergo surgery and the tumour staging would have relied on clinical tumour stage only. Patients residing in Middle Norrland and Upper Norrland areas, and in North and Uppsala-Örebro healthcare regions, were more likely to be diagnosed at an advanced stage, and the underlying reasons warrant further investigation. Possible explanations may include patient delay due to less accessibility to healthcare or personal reasons, primary care delay in the referral of patients to specialised care or health system delay or limited resources in these regions. Patients residing in the Stockholm area had higher chance of being diagnosed at an early stage compared with those in other counties. This may be explained by the easier accessibility to the specialised upper gastrointestinal oncology and surgery units, that are located in the metropolitan area of Stockholm county. However, this early diagnosis did not extend to the Gotland county (16 [37%] out 43 cases diagnosed at tumour stage IV), although Gotland county is also included in the Stockholm healthcare region but located far away from these specialised units. Therefore, accessibility to specialised medical care may be an important factor explaining the geographical variation in tumour stage distribution of oesophageal cancer in Sweden.

In summary, this nationwide analysis of data from a complete cancer registry highlighted considerable geographical variations in the incidence of oesophageal cancer in Sweden, particularly for oesophageal adenocarcinoma in men in recent years. Additionally, patients residing in certain geographical and healthcare regions tend to be diagnosed with oesophageal cancer at a more advanced stage compared with those in other regions, and future research is needed to identify the underlying reasons for improved outcomes in patients throughout the country.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (169.1 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lagergren J, Smyth E, Cunningham D, et al. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet. 2017;390(10110):2383–2396.

- Xie SH, Mattsson F, Lagergren J. Incidence trends in oesophageal cancer by histological type: an updated analysis in Sweden. Cancer Epidemiol. 2017;47:114–117.

- Xie SH, Lagergren J. Social group disparities in the incidence and prognosis of oesophageal cancer. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(3):343–348.

- Pan R, Zhu M, Yu C, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality: a cohort study in China, 2008–2013. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(7):1315–1323.

- Wang Z, Goodman M, Saba N, et al. Incidence and prognosis of gastroesophageal cancer in rural, urban, and metropolitan areas of the United States. Cancer. 2013;119(22):4020–4027.

- Ljung R, Drefahl S, Andersson G, et al. Socio-demographic and geographical factors in esophageal and gastric cancer mortality in Sweden. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62067.

- Lindblad M, Ye W, Lindgren A, et al. Disparities in the classification of esophageal and cardia adenocarcinomas and their influence on reported incidence rates. Ann Surg. 2006;243(4):479–485.

- Statistics Sweden. EU:s regioner – NUTS [internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/internationell-statistik/eu-statistik/eus-regioner—nuts/.

- Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting. Representanter sjukvårdsregionerna [internet]. [cited 2019 Jul 31]. Available from: https://skl.se/halsasjukvard/kunskapsstodvardochbehandling/systemforkunskapsstyrning/nationellaprogramomraden/samverkanforkunskapsstyrning/representantersjukvardsregionerna.9687.html.

- Brusselaers N, Vall A, Mattsson F, et al. Tumour staging of oesophageal cancer in the Swedish Cancer Registry: a nationwide validation study. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(6):903–908.

- Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz M, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th ed. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009.

- Coleman HG, Xie SH, Lagergren J. The epidemiology of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(2):390–405.

- Ness-Jensen E, Lindam A, Lagergren J, et al. Changes in prevalence, incidence and spontaneous loss of gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a prospective population-based cohort study, the HUNT study. Gut. 2012;61(10):1390–1397.

- Neovius M, Janson A, Rossner S. Prevalence of obesity in Sweden. Obes Rev. 2006;7(1):1–3.

- Agreus L, Hellstrom PM, Talley NJ, et al. Towards a healthy stomach? Helicobacter pylori prevalence has dramatically decreased over 23 years in adults in a Swedish community. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:686–696.

- The Public Health Agency of Sweden (Folkhälsomyndigheten). FolkhälsoStudio. [cited 2019 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/datavisualisering.

- Patja K, Hakala SM, Bostrom G, et al. Trends of tobacco use in Sweden and Finland: do differences in tobacco policy relate to tobacco use? Scand J Public Health. 2009;37(2):153–160.

- Kraus L, Tinghog ME, Lindell A, et al. Age, period and cohort effects on time trends in alcohol consumption in the Swedish adult population 1979-2011. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50(3):319–327.

- Branstrom R, Andreasson S. Regional differences in alcohol consumption, alcohol addiction and drug use among Swedish adults. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36:493–503.