Abstract

Aims: Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a slowly progressive disease, often transmitted among people who inject drugs (PWID). Mortality in PWID is high, with an overrepresentation of drug-related causes. This study investigated the risk of death in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection with or without illicit substance use disorder (ISUD).

Methods: Patients with HCV were identified using the Swedish National Patient Registry according to the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) code B18.2, with ≤5 matched comparators from the general population. Patients with ≥2 physician visits with ICD-10 codes F11, F12, F14, F15, F16, or F19 were considered to have ISUD. The underlying cause of death was analyzed for alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic liver disease, liver cancer, drug-related and external causes, non-liver cancers, or other causes. Mortality risks were assessed using the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) with 95% CIs and Cox regression analyses for cause-specific hazard ratios.

Results: In total, 38,186 patients with HCV were included, with 31% meeting the ISUD definition. Non-alcoholic liver disease SMRs in patients with and without ISUD were 123.2 (95% CI, 103.7–145.2) and 69.4 (95% CI, 63.8–75.3), respectively. The significant independent factors associated with non-alcoholic liver disease mortality were older age, being unmarried, male sex, and having ISUD.

Conclusions: The relative risks for non-alcoholic liver disease mortality were elevated for patients with ISUD. Having ISUD was a significant independent factor for non-alcoholic liver disease. Thus, patients with HCV with ISUD should be given HCV treatment to reduce the risk for liver disease.

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major health issue, with an estimated 69 million patients chronically infected in the world [Citation1]. In recent years, HCV treatment paradigms have changed from interferon-based treatment to oral interferon-free direct-acting antivirals. Today, most patients receive 8 to 12 weeks of treatment, with cure rates >95% [Citation2]. The main route for HCV transmission in Europe and North America is use of non-sterile drug paraphernalia [Citation3]. Thus, to eliminate HCV, it is crucial to control the epidemic among people who inject drugs (PWID). Several studies have shown that patients in opioid agonist therapy (OAT) have similar HCV cure rates as those without injection drug use (IDU). Studies have shown successful treatment outcomes in primary healthcare settings and community-based programs, with access to needle syringe programs (NSP) [Citation4]. Reinfection after virologic cure is a major risk in PWID with continuous risk behavior [Citation5]. Harm reduction interventions, such as OAT and NSP, are thus needed to reduce HCV transmission and the risk of reinfection in PWID [Citation6].

The mortality among PWID is high due to an increased risk of death from external causes (e.g. accidents, assaults, drug overdoses, suicides), mental and behavioral disorders, and HIV infection and liver-related complications [Citation7–9]. Since HCV-related liver disease has a slow progression, liver cirrhosis will develop in approximately 20% to 30% of the patients but only after 20 to 30 years [Citation10]. The lack of disease symptoms and barriers to treatment access among both patient and healthcare providers have resulted in limited HCV treatment uptake in PWID [Citation11,Citation12]. The treatment complexity of the interferon-era, and limited access to NSP and other low-threshold platforms where PWID could be reached have been further obstacles [Citation11,Citation12]. Swedish patients with chronic HCV infection have an elevated risk of death from psychiatric and external causes, mainly at younger age, and with age an increased risk for liver-related mortality [Citation13]. In the present study, we examined the risk of death in patients with chronic HCV with or without illicit substance use disorder (ISUD).

Materials and methods

Setting

Access to healthcare in Sweden is universal through a tax-funded system. Historically, HCV care in Sweden is provided by specialists in infectious diseases, or in gastroenterology or hepatology at hospital-based inpatient and outpatient clinics rather than in primary care [Citation14]. Although OAT gradually has become more widely available in Sweden during the last two decades, access to NSP is still limited [Citation15].

Data sources and study populations

The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare maintain the Swedish National Patient Register (NPR) [Citation16], which contains all inpatient (from 1987) and outpatient care visits (from 2001) except primary care visits. Patients were defined to have chronic HCV and identified in the NPR using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) code B18.2 (introduced in 1997), if they had 2 positive HCV RNA tests over >6 months. The Total Population Register that covers the Swedish population was used to retrieve information regarding age, sex, and place of residence, as well as dates of birth and emigration status (until 31 December 2013) [Citation17]. The Cause of Death Registry was used to retrieve information on deaths [Citation16]. The Longitudinal Integrated Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies was used to obtain the highest attained education level [Citation17]. Before anonymization, the linking between the registers was performed using the unique Swedish personal identity number (i.e. social security number). Patients were included in the study at the first HCV visit starting 1 January 2001 (the index date). For each patient with HCV, up to 5 comparators from the general population were matched by age, sex, and county of residence at the index date. The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Stockholm, Sweden.

Observation time

The starting point for the study was 1 January 2001, corresponding to the date from which outpatient care data was included in the NPR. The observation time started at the index date and ended at time of death, emigration, or 31 December 2013, whichever came first.

Assessments

ISUD was defined using the ICD-10 diagnosis according to the “Selection B” criteria defined by the European Monitor Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction [Citation18] that includes mental and behavioral disorders related to the use of opioids (F11), use of cannabinoids (F12), use of cocaine (F14), use of other stimulants (F15), use of hallucinogens (F16), or multiple drug use and use of other psychoactive substances (F19). To reduce the risk of incorrect entry of diagnosis data in the registry, ≥2 non-primary care ISUD visits were required as inclusion criteria. Thus, patients with only 1 non-primary care visit with ISUD diagnosis during the study period were excluded from the analysis. To reduce the risk of surveillance bias, a lag-period was introduced to exclude patients who died within 6 months of chronic HCV diagnosis (). Disease-specific causes of death were analyzed by the following sub-groups: liver cancer, alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic liver disease, drug-related causes, external causes, external and drug-related causes, non-liver cancers, and other causes (Table S1) [Citation19], as well as an aggregated all liver disease group including alcohol liver disease, non-alcoholic liver disease, and liver cancer. The ICD-10 codes B18.0 and B18.1 were used for chronic HBV infection and B20–B24 were used for HIV.

Analyses

Crude mortality rate was used to describe the number of deaths per 1,000 person-years (PY) without considering differences in demographics. Standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated by dividing the observed number of deaths (all-cause or by cause-specific) with the expected number of deaths based on the mortality rate per 1,000 PY in the matched comparator cohort. The mortality risk was analyzed using hazard ratio (HR) Cox regression analysis. Cause-specific HR (csHR) was used to evaluate the risk of death from specific causes by considering other deaths as competing risks [Citation20]. Both univariate and forward multivariate stepwise Cox regression models were used to analyze HRs and csHRs. The analysis has not been pre-registered, and the results should thus be considered exploratory. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for data handling, and the data were analyzed using SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patient selection, demographics and baseline disease characteristics

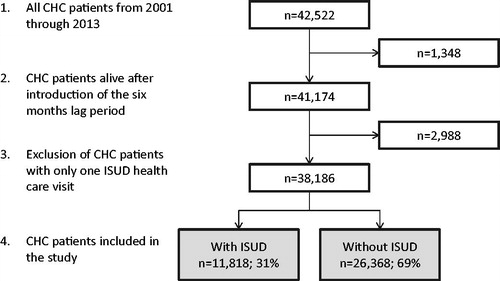

In total, 42,522 individuals were diagnosed with HCV from 2001 through 2013. After the introduction of the 6-month lag-period, 41,174 patients remained. Individuals with only one ISUD visit were excluded, leaving 38,186 patients with HCV included in the final analyses. Nearly one-third (n = 11,818; 31%) of these also fulfill the ISUD criteria (). Patients with HCV with or without ISUD were followed for 83,701 PY and 177,659 PY, respectively. The corresponding number of individuals in the matched cohorts were 57,084 (patients with ISUD) and 126,751 (patients without ISUD) followed for 434,604 PY and 944,867 PY, respectively.

Patients with ISUD were, in comparison to patients without ISUD, more likely to be men (72% vs. 62%), of Swedish origin (86% vs. 76%), chronically infected with HBV (12% vs. 9%), infected with HIV (3% vs. 2%), unmarried (92% vs. 72%), and to have a lower educational level (<9 years: 49% vs. 31%). In addition, patients with ISUD were younger at inclusion (mean age of 37.7 vs. 46.9 years) ().

Table 1. Baseline demographics for patients with or without ISUD.

Crude mortality rate

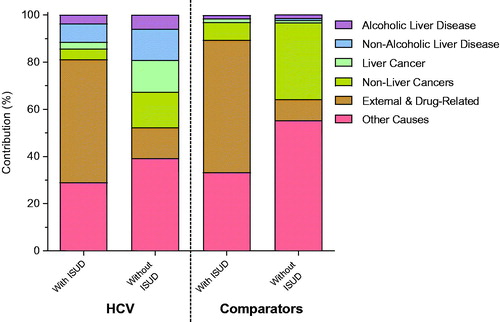

There were 1,815 deaths (15%; 21.7 per 1,000 PY) among patients with ISUD and 4,272 deaths (16%; 24.0 per 1,000 PY) among patients without ISUD (). shows the absolute contribution for causes of death in patients with and without ISUD, respectively; for alcoholic liver disease (4% vs. 6%), non-alcoholic liver disease (8% vs. 13%), liver cancer (3% vs. 13%), non-liver cancers (4% vs. 15%), external and drug-related causes (52% vs. 13%), and other causes (29% vs. 39%). There were 66 deaths (8%; 10.1 per 1,000 PY) among comparator with ISUD (defined as ≥2 non-primary care ISUD visits during the observation time) and 6,347 deaths (4%; 4.7 per 1,000 PY) among comparators without ISUD (defined as 0 non-primary care ISUD visits during the observation time). The absolute contribution for causes of death in comparators with and without ISUD, respectively; for alcoholic liver disease (2% vs. 1%), non-alcoholic liver disease (0% vs. 1%), liver cancer (2% vs. 1%), non-liver cancers (8% vs. 33%), external and drug-related causes (56% vs. 9%), and other causes (33% vs. 55%) ().

Figure 2. Absolute contribution of cause of death per disease inclusion for patients with HCV with or without ISUD and comparators with or without ISUD. HCV: chronic hepatitis C; ISUD: illicit substance use disorder.

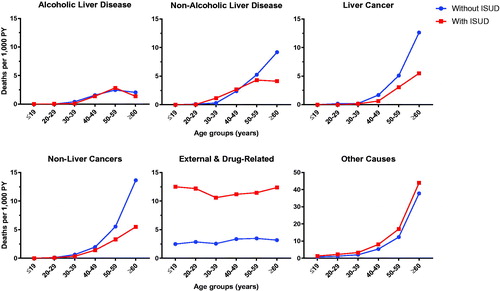

Patients with ISUD were younger than those without ISUD, thus the overall crude mortality rate was expected to be lower in patients with ISUD. As a result, we analyzed the crude mortality rates according to age at inclusion and according to cause of death. The crude mortality rates due to external and drug-related causes were higher for patients with ISUD in all age groups compared to patients without ISUD. The crude mortality rates for both liver and non-liver cancers were higher in patients without ISUD in the older age groups, whereas the crude mortality rate from other causes was higher in patients with ISUD. For alcoholic liver disease, the crude mortality rate was similar between the two groups. For non-alcoholic liver disease, the crude mortality rate was higher in patients with ISUD in persons aged 30–39 years, but lower in those aged ≥50 years ().

All-cause and cause-specific relative risk for patients with and without illicit substance use disorder – standardized mortality ratios

The all-cause SMRs were 10.5 (95% CI, 10.0–11.0) and 4.1 (95% CI, 3.9–4.2) for patients with and without ISUD, respectively (). The relative risk was elevated for all investigated cause-specific diseases in both patient cohorts. Non-alcoholic liver disease had the highest SMRs in patients with ISUD (123.2 [95% CI, 103.7–145.2] and in patients without ISUD (69.4 [95% CI, 63.8–75.3]) ().

Table 2. All-cause and cause-specific standardized mortality ratios for patients with or without ISUD.

The elevated relative risk of death from non-alcoholic liver disease was mainly driven by age, in patients aged <50 years at inclusion with and without ISUD (SMRs, 522.8 [95% CI, 425.8–635.2] and 89.8 [95% CI, 76.3–105.0], respectively) and in men with and without ISUD (SMRs, 199.5 [95% CI, 164.6–239.7] and 77.2 [95% CI, 69.6–85.5], respectively). However, the relative risk was also elevated in patients aged >50 years with and without ISUD at inclusion (SMRs, 44.5 [95% CI, 31.9–60.4] and 66.9 [95% CI, 60.6–73.8], respectively) and in women with and without ISUD (SMRs, 47.6 [95% CI, 31.6–68.7] and 57.8 [95% CI, 49.8–66.6]).

Univariate and multivariate analyses of independent risk factors for overall mortality and cause-specific mortality – Cox regression analyses

The univariate Cox regression analysis for all-cause mortality showed elevated mortality for the following risk factors: older age, lower level of education, being unmarried, chronic HBV infection, male sex, and having ISUD (). These elevated risk factors remained in the stepwise multivariate Cox regression analysis (). The significant independent risk factors for death due to non-alcoholic liver disease in patients with HCV were older age, being unmarried, male sex, and having ISUD (). As presented in Table S2, the independent risk factors for: 1) alcoholic liver disease mortality were older age, chronic HBV infection, and male sex; 2) all liver disease were older age, male sex, and chronic HBV infection; 3) liver cancer mortality were older age, male sex, and having no ISUD; 4) non-liver cancers mortality were older age and HIV infection; 5) external and drug-related causes mortality were being unmarried, male sex, and having ISUD; and 6) other causes mortality were older age, lower educational level, being unmarried, chronic HBV infection, and having ISUD.

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis of various risk factors for all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality.

Discussion

Most new HCV infections in the developed world occur in PWID. Earlier studies have shown that PWID have a higher risk to die from violent and drug-related causes [Citation7–9]. In the present study, we analyzed the cause of death in patients with chronic HCV using drugs and identified nearly one-third of the patients with HCV as having current ISUD during the observation period. It has previously been shown that most Swedish patients with HCV have IDU as the main route of transmission [Citation21].

Among the patients with ISUD, a higher proportion were men, unmarried, younger at inclusion, had a lower educational level, had chronic HBV or HIV infection, and were of Swedish origin. In line with earlier studies, ISUD patients with HCV had an elevated relative mortality risk and died at a younger age [Citation7–9]. The crude mortality rates for most death causes increased with age at inclusion, except for external and drug-related causes for which the rates were similar across all age groups. Thus, direct unadjusted comparisons between patients with and without ISUD may be biased due to the younger age in patients with ISUD. As a result, we found it more relevant to analyze the relative mortality risk in both groups by standardizing the all-cause and cause-specific mortality risk to matched comparators. The relative risk for non-alcoholic liver disease mortality was substantially elevated in patients both with and without ISUD. However, the relative risk will only provide information on the risks within each group and should not be used for a direct comparison of the relative risks between the two cohorts. In order to better determine the independent impact of risk factors on all-cause and cause-specific mortalities were multivariate analyses done. Interestingly, the multivariate analysis indicated that having ISUD was associated with a 71% higher independent risk to die from non-alcoholic liver disease (). On the other hand, ISUD was significantly associated with a lower risk to die from liver cancer (Table S2). The risk to die from all liver disease, however, was independent of having ISUD or not.

Several recreational drugs, such as ecstasy/MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine), cocaine, and cannabis, have been associated with liver disease [Citation22–24]. Also, an association between IDU and excessive alcohol consumption has previously been shown [Citation25,Citation26]. Even though ISUD was not associated with an elevated mortality risk due to alcoholic liver disease, alcohol cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor for progression to non-alcoholic liver disease in patients with ISUD, as episodes with heavy drinking are associated with fibrosis progression [Citation27]. A study in Swedish PWID participating in NSP showed a significant increase in some specific types of cancer (including primary liver, laryngeal, lung, oropharyngeal and non-melanoma skin cancer), suggesting that IDU is somehow associated with an elevated risk for several malignancies [Citation28].

From a public health perspective, there are two main reasons to treat and cure patients with HCV. By reducing the number of patients with viremic disease, the risk of transmission decreases. In Iceland, the comprehensive HCV elimination efforts and increased treatment rates have resulted in a drop in HCV incidence among PWID during the first year of IDU from 13% in 2013–2016 to 0% in 2017–2018 [Citation29]. Furthermore, curing HCV will reduce or minimize liver disease progression, and with time prevent end-stage liver disease and liver cancer [Citation30,Citation31].

The HCV epidemic in Europe and North America is mainly driven by PWID. Previously, and still present in some regions, a scale-up of HCV treatment among PWID has been controversial, largely because of the fear of compliance issues and the risk of reinfections [Citation32]. In a recent Australian study including PWID with a high proportion of individuals with continued risk behavior after treatment, a reinfection rate of 12.4 per 100 PY was noted [Citation33]. Nevertheless, several recdent studies in PWID have shown promising results, with high adherence rates and relatively low reinfections rates (2–6 per 100 PY) [Citation32,Citation34,Citation35]. HCV treatment scale-up without concomitant harm reduction measures, such as OAT and NSP, will make HCV elimination infeasible. A recent Cochrane review concluded that the greatest risk reduction of new HCV infection was observed with the combined use of OAT and NSP [Citation6]. On a national level, implementation of NSP in Sweden has been slow, although some regions have had good access to NSP since the late 1980s. Longitudinal studies among NSP participants from such regions, however, have noticed that a high prevalence and incidence of HCV infection remains, despite efficient prevention of HIV and HBV infection [Citation36], indicating the need to implement HCV treatment to combat the epidemic.

Eradication of HCV is an important factor in reducing the level of liver-related mortality [Citation37]. A strength in our study is the large number of individuals included from the Swedish patient registry. The registries used in our study, however, do not capture HCV treatment outcomes. Hence, the impact of sustained virological response on mortality could not be evaluated. All the same, since treatment uptake has been very low in PWID in Sweden so far, one possible explanation for the higher risk of non-alcoholic liver disease in patients with ISUD is that only a small portion of patients with HCV and ISUD have been treated. Further studies to assess the impact of viral eradication on causes of death in patients with HCV and ISUD in conjunction with HCV eliminations projects are warranted. A further limitation of our study is that primary care data is missing. In Sweden, however, in-hospital specialists exclusively cared for patients with HCV at the time of the study. Another limitation is that the registries contain no information on important lifestyle factors, such as smoking habits, daily alcohol consumption that can cause liver-related mortality. Hence, these factors could not be evaluated [Citation37]. Also, there is a potential for bias to put unspecific liver diseases as the cause of death for individuals with known HCV although it in part could be caused by excessive alcohol use.

In conclusion, the major cause of death in patients with ISUD was external and drug-related causes. Nevertheless, we showed that ISUD is a significant risk factor for non-alcoholic liver disease mortality. These data highlight the importance of HCV treatment among people with ISUD.

Author contributions

The concept of the study was designed by MK and JS. JS managed the database and performed the analyses. MK, OW, and JS interpreted the data with support from SBL, AJ, AN, ASD, JK, MY, SA, KB, and MAB. MK, OW, and JS wrote the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version that was submitted.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (104.3 KB)Disclosure statement

SBL has nothing to disclose. AJ has received research support from AbbVie. AN has received honoraria for advisory boards/lectures from Abbvie, MSD, and Gilead and has received research support from AbbVie. ASD has received honoraria for lectures/consultancies from AbbVie, BMS, Gilead, and MSD. MY has received honoraria for lectures from AbbVie, Gilead, and MSD. SA has received honoraria for lectures/advisory boards from AbbVie, BMS, Gilead, and MSD and received research grants from AbbVie and Gilead. MAB has received honoraria for advisory boards/lectures from Abbvie, MSD, and Gilead and has received research support from AbbVie. OW has consultancies with AbbVie, BMS, Gilead, and MSD/Merck and has worked on speakers bureaus for AbbVie, BMS, Gilead, and MSD/Merck. MK has received honoraria for lectures from AbbVie, Gilead, and MSD and received research grants from Gilead. JS and JK are employees of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stocks or stock options. KB is a former employee of AbbVie and may hold AbbVie stocks or stock options.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Heffernan A, Cooke GS, Nayagam S, et al. Scaling up prevention and treatment towards the elimination of hepatitis C: a global mathematical model. Lancet. 2019;393(10178):1319–1329.

- Spengler U. Direct antiviral agents (DAAs) – a new age in the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;183:118–126.

- Thursz M, Fontanet A. HCV transmission in industrialized countries and resource-constrained areas. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11(1):28–35.

- Grebely J, Hajarizadeh B, Dore GJ. Direct-acting antiviral agents for HCV infection affecting people who inject drugs. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(11):641–651.

- Falade-Nwulia O, Sulkowski MS, Merkow A, et al. Understanding and addressing hepatitis C reinfection in the oral direct acting antiviral era. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(3):220–227.

- Platt L, Minozzi S, Reed J, et al. Needle and syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing HCV transmission among people who inject drugs: findings from a Cochrane Review and meta‐analysis. Addict Abingdon Engl. 2018;113(3):545–563.

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Bucello C, et al. Mortality among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(2):102–123.

- Jerkeman A, Håkansson A, Rylance R, et al. Death from liver disease in a cohort of injecting opioid users in a Swedish city in relation to registration for opioid substitution therapy: liver mortality in opiate substitution therapy. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2017;36(3):424–431.

- Åhman A, Jerkeman A, Blomé MA, et al. Mortality and causes of death among people who inject amphetamine: a long-term follow-up cohort study from a needle exchange program in Sweden. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;188:274–280.

- Thein H-H, Yi Q, Dore GJ, et al. Estimation of stage-specific fibrosis progression rates in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Hepatology. 2008;48(2):418–431.

- Grebely J, Genoway KA, Raffa JD, et al. Barriers associated with the treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among illicit drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93(1-2):141–147.

- Wright C, Cogger S, Hsieh K, et al. I’m obviously not dying so it’s not something I need to sort out today”: considering hepatitis C treatment in the era of direct acting antivirals. Infect Dis Health. 2019;24(2):58–66.

- Duberg A-S, Törner A, Daviðsdóttir L, et al. Cause of death in individuals with chronic HBV and/or HCV infection, a nationwide community-based register study. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15(7):538–550.

- Büsch K, Waldenström J, Lagging M, et al. Prevalence and comorbidities of chronic hepatitis C: a nationwide population-based register study in Sweden. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(1):61–68.

- Kåberg M, Hammarberg A, Lidman C, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C and pre-testing awareness of hepatitis C status in 1500 consecutive PWID participants at the Stockholm needle exchange program. Infect Dis. 2017;49(10):728–736.

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. [cited 2018 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/register.

- Statistics Sweden. Statistiska Centralbyrån. [cited 2018 Sep 7]. Available from: http://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/

- EMCDDA. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. [cited 2019 Mar 29]. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/stats07/DRD/methods

- Innes H, McDonald S, Hayes P, et al. Mortality in hepatitis C patients who achieve a sustained viral response compared to the general population. J Hepatol. 2017;66(1):19–27.

- Donoghoe MW, Gebski V. The importance of censoring in competing risks analysis of the subdistribution hazard. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2017;17(1):52.

- Duberg A, Janzon R, Bäck E, et al. The epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection in Sweden. Eurosurveillance. 2008;13(21):18882.

- Hézode C, Zafrani ES, Roudot–Thoraval F, et al. Daily cannabis use: a novel risk factor of steatosis severity in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(2):432–439.

- Mallat A, Dhumeaux D. Cocaine and the liver. J Hepatol. 1991;12(3):275–278.

- Andreu V, Mas A, Bruguera M, et al. Ecstasy: a common cause of severe acute hepatotoxicity. J Hepatol. 1998;29(3):394–397.

- Irvin R, Chander G, Falade-Nwulia O, et al. Overlapping epidemics of alcohol and illicit drug use among HCV-infected persons who inject drugs. Addict Behav. 2019;96:56–61.

- Kåberg M, Edgren E, Hammarberg A, et al. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) related liver fibrosis in people who inject drugs (PWID) at the Stockholm Needle Exchange – evaluated with liver elasticity. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(3):319–327.

- Ekstedt M, Franzén LE, Holmqvist M, et al. Alcohol consumption is associated with progression of hepatic fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(3):366–374.

- Reepalu A, Blomé MA, Björk J, et al. The risk of cancer among persons with a history of injecting drug use in Sweden – a cohort study based on participants in a needle exchange program. Acta Oncol. 2012;51(1):51–56.

- Tyrfingsson T, Runarsdottir V, Hansdottir I, et al. Treatment as prevention approach results in early and marked prevalence reduction of hepatitis C viremia among people who recently injected drugs. Results from Iceland: Treatment as Prevention (TraP HepC). In: Vol 2018. [cited 2019 Feb 4]. Available from: https://az659834.vo.msecnd.net/eventsairaueprod/production-ashm-public/a968ad26f85943de9eb56faf83bbbcdf

- Cacoub P, Gragnani L, Comarmond C, et al. Extrahepatic manifestations of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:S165–S173.

- Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G. Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1):S58–S68.

- Rossi C, Butt ZA, Wong S, et al. Hepatitis C virus reinfection after successful treatment with direct-acting antiviral therapy in a large population-based cohort. J Hepatol. 2018;69(5):1007–1014.

- Aitken CK, Agius PA, Higgs PG, et al. The effects of needle-sharing and opioid substitution therapy on incidence of hepatitis C virus infection and reinfection in people who inject drugs. Epidemiol Infect. 2017;145(4):796–801.

- Midgard H, Weir A, Palmateer N, et al. HCV epidemiology in high-risk groups and the risk of reinfection. J Hepatol. 2016;65(1):S33–S45.

- Cunningham EB, Amin J, Feld JJ, et al. Adherence to sofosbuvir and velpatasvir among people with chronic HCV infection and recent injection drug use: the SIMPLIFY study. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;62:14–23.

- Blomé MA, Björkman P, Flamholc L, et al. Minimal transmission of HIV despite persistently high transmission of hepatitis C virus in a Swedish needle exchange program. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18(12):831–839.

- Vandenbulcke H, Moreno C, Colle I, et al. Alcohol intake increases the risk of HCC in hepatitis C virus-related compensated cirrhosis: a prospective study. J Hepatol. 2016;65(3):543–551.