Abstract

Objectives

Patients with ulcerative colitis are at increased risk for colorectal cancer, especially at younger ages. Our aim was to determine, in our patient cohort, the clinicopathological features, incidence, and prognosis of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer.

Materials and methods

A single-center, population-based study including all 1241 patients with ulcerative colitis who underwent surgery in Helsinki University Hospital, 1991–2018. All data were from medical records, collected retrospectively.

Results

In total, 71 patients with ulcerative colitis-associated cancer were operated on in Helsinki University Hospital during 1991–2018; 108 patients undergoing surgery during 2002–2018 showed dysplasia in the surgical specimen. Cancer was diagnosed preoperatively in 47 patients (66.2%). Ten patients (14.1%) had synchronous colorectal cancer, and 24 (33.8%) had synchronous dysplasia. The incidence of colorectal cancer has not changed during the study period (p = .113). Overall survival was 71.8%, and the 5-year colorectal cancer-specific survival was 81.5%.

Conclusion

The incidence of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer remained constant in our study population over three decades. The prognosis of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer and the prognosis of sporadic colorectal cancer were comparable. One-third of the cancers were not diagnosed in preoperative colonoscopy, and the indication for surgery in such cases was dysplasia. We therefore do not recommend the endoscopic management of ulcerative colitis-associated dysplasia.

Introduction

The association between ulcerative colitis (UC) and colorectal cancer (CRC) is well known. The first ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer was described by Crohn and Rosenberg in 1925 [Citation1]. The risk factors identified for CRC in UC patients are pancolitis, young age, long disease duration, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and family history of colorectal cancer [Citation2]. A meta-analysis in 2014 reported a risk for CRC in UC patients that has decreased over recent decades. They found an overall risk for CRC of 1.69%, and the cumulative risk was 0.91% at 10 years after diagnosis, 4.07% at 20 years, and 4.55% at 30 years [Citation3]. Speculation is that new treatment modalities and colectomies earlier after diagnosis of dysplasia may explain this decline in incidence. In addition, the development of endoscopic equipment enabling earlier detection of dysplastic lesions might also play part in declining incidence. Biological medication suppresses the inflammation, possibly reducing risk for dysplasia; moreover, 5-ASA may exert a chemo-preventive effect [Citation4,Citation5].

Patients with UC-associated CRC are often younger, with more multifocal, mucinous, and signet-ring cell carcinomas—findings related to poorer prognosis—than are patients with sporadic CRC. Earlier data seems to show that UC-associated CRC has a 2-fold higher mortality than that of sporadic colorectal cancers [Citation6].

This study presents the results of a high-volume tertiary referral center performing UC surgery. Our aim was to clarify the clinicopathological features, incidence and prognosis of UC-associated colorectal cancer in our patient cohort.

Materials and methods

In this retrospective, population-based, single-center study, we included all patients who underwent surgery during the years 1991–2018 in Helsinki University Hospital for ulcerative colitis or indeterminate colitis and had colorectal cancer in their surgical specimen. Moreover, we analyzed patients with dysplasia of their surgical specimens during 2002–2018. We did not have data available on patients with dysplasia before year 2002. Preoperatively, two independent and experienced gastropathologists always made the diagnosis of UC-associated dysplasia from biopsies performed during the colonoscopy. If the diagnosis was dysplasia, indications for surgery were multifocal low- or high-grade dysplasia, low-grade dysplasia in consecutive colonoscopies, or high-grade dysplasia or a DALM lesion in a single colonoscopy.

We collected all data from medical records including gender, age, disease duration, surveillance colonoscopy details, primary sclerosing cholangitis, indication for and type of surgery, tumor site (rectum or colon), histological type, the presence of lymph node or distant metastasis, cancer recurrence, survival, and causes of death. If there was any suspicion of cancer preoperatively, the indication for surgery was reported as cancer despite the findings in preoperative biopsy specimens. Grading and staging are expressed according to the 7th UICC TNM Classification. During the study period multiple different staging systems were used, including Dukes classification, and therefore substaging was not possible to be reported in our study. For multifocal tumors, we presented histopathological results for the one tumor which was most advanced.

Statistical analysis utilized IBM SPSS Statistics software version 24 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). To determine whether cancer incidence in patients undergoing surgery for UC has changed over the years, we split the data into two equally long periods and compared those groups with the Chi-square test. Survival was analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method, with cancer-specific death as the outcome and was compared by log rank test. Patients who died from other causes or who were still alive at the end of follow-up were censored. p values less than .05 we considered significant. See tables for missing data. The institutional review board approved the study.

Results

Patient characteristics

In total, 71 patients with UC-associated cancer underwent surgery in Helsinki University Hospital during 1991 to 2018 (). During that same period, 1170 patients with ulcerative colitis underwent proctocolectomy for other indications. The median disease duration was 19.0 years (0–50 years); 13 (18.3%) patients had primary sclerosing cholangitis. Surgical procedures were proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (PC + IPAA, 55, 77.5%), proctocolectomy with ileostomy (5, 7.0%), and colectomy with or without an anastomosis (10, 14.1%). In addition, one patient had a prior proctocolectomy with a stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis and developed cancer of the rectal remnant. She was treated with excision of the pouch and a permanent ileostomy.

Table 1. Characteristics of colorectal cancer patients (n = 71).

The cancer was diagnosed preoperatively in most patients (47, 66.2%). It is noteworthy that in one-third of the CRC patients the indication for surgery was dysplasia and there was no endoscopic suspicion of cancer. However, these patients had cancer in their surgical specimen (22 patients, 31.0%).

In 20 patients (28.2%), the cancer was situated in the rectum, and in 51 (71.8%), in the colon. Ten patients (14.1%) had synchronous colorectal cancer, and 24 (33.8%) had synchronous dysplasia. In the pathological examination, almost one-third of the cancers (22 patients, 31.0%) were mucinous adenocarcinomas, and in 14 (19.7%), the cancers were poorly differentiated. The cancer had spread to the nearby lymph nodes in 20 patients (28.2%, TNM stage III), and 7 (9.9%, TNM stage IV) had metastatic disease at surgery.

In addition, of UC patients who underwent proctocolectomy with or without ileal pouch-anal anastomosis during 2002-2018, 108 had dysplasia but no cancer in the surgical specimen (). Of these, 36 (33.3%) had high-grade dysplasia.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients with dysplasia in the surgical specimen (n = 108).

Cancer incidence

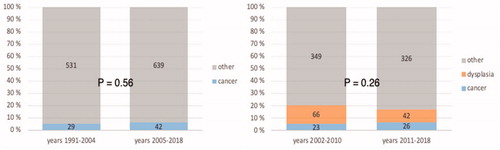

Among all patients operated on for ulcerative colitis in Helsinki University Hospital during 1991 to 2018, the incidence of colorectal cancer had not increased (p = .56) (). If those patients undergoing surgery for dysplasia were added, the results remained the same (years 2002–2018, p = .260).

Survival

The median follow-up time was 8.2 years (0.6–26.8). Cancer recurrence occurred in 17 patients (23.9%). In total, 20 patients (28.2%) died during follow-up, of whom 14 (19.7%) died of the colorectal cancer. Other causes of death were primary sclerosing cholangitis, cholangiocarcinoma, lung cancer, neuroendocrine carcinoma, cerebral hemorrhage, and Alzheimer disease. The mean age of death was 55.7 ± 13.5 years.

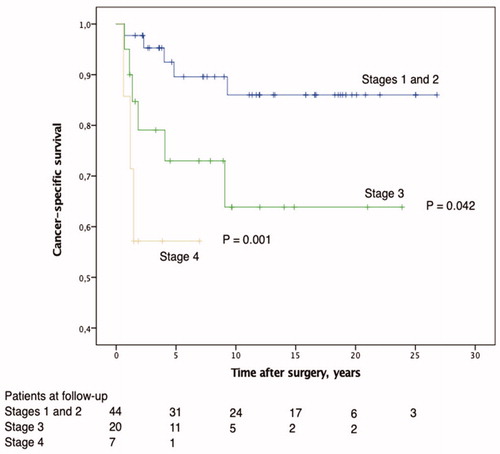

At the end of follow-up, overall survival was 71.8%. CRC-specific survival was 76.5%; 89.6% at stages I and II, 73.0% at stage III, and 57.1% at stage IV. The survival rate was significantly higher for those with tumors at stages I and II than with stage III (p = .042) and stage IV tumors (p < .001) (). The 5-year CRC-specific survival rate was 81.5%: 77.3% for men and 87.8% for women.

Discussion

The 5-year CRC-specific survival in all Finnish CRC patients at the end of 2017 was 64.2% for men and 66.7% for women, according to the Finnish nationwide cancer registry (1, website). Our figures for UC-associated CRC were no lower than those. The comparison is a bit unfair, however, because our patient cohort comprised only those patients who underwent surgery. As expected, cancer-specific survival rate correlated well with UICC stage. Unfortunately, the Finnish nationwide cancer registry provides no stage-specific survival data for comparison.

Few studies compare overall cancer-specific survival between UC-associated CRC and sporadic CRC, and their results have been conflicting. In one Japanese population, Watanabe et al. found no difference in 5-year overall survival rates between UC-associated CRC patients and sporadic CRC patients (64.2% vs 68.7%) [Citation7]. When the groups were compared according to stage, UC-associated CRC patients had significantly lower 5-year overall survival rate in stage III, but cancer-specific survival rates did not differ at any stage. In a large retrospective study from the Mayo Clinic, the 5-year overall survival rate of UC-associated CRC patients was 55%, which did not differ from rates for sporadic CRC patients. In one subgroup analysis, however, UC patients with stage-II tumors had poorer outcome, no cancer-specific survival was provided in their analysis [Citation8]. A recent matched-pair analysis from Germany also found a significant difference in patients with stage-II cancer regarding recurrence-free survival in favor of sporadic cancers, but no difference appeared in overall- and cancer-specific survival rates [Citation9]. In Norway, a study reported worse overall survival rates in UC patients; moreover, synchronous dysplasia or cancer seemed to be related to poorer prognosis [Citation10]. A large registry-based Danish study also showed poorer outcome for UC-associated CRC patients when adjusted for sex, age, year of diagnosis, stage, and comorbidities. Conspicuously, 41% of the patients were diagnosed with CRC within one year of UC diagnosis [Citation11].

The European evidence-based consensus on surgery (ECCO Guidelines) recommends performing the first surveillance colonoscopy on patients with ulcerative colitis eight years after the diagnosis and scheduling the next one for one to five years thereafter, depending on the patient’s risk factors [Citation4]. Patients with PSC should be monitored annually. Most of the patients in our study were under routine surveillance, but nine patients (12.7%) developed cancer within the first eight years after UC diagnosis. This finding makes us wonder if the first surveillance colonoscopy should be scheduled earlier than eight years after the diagnosis.

In our patient cohort, a great proportion of dysplastic lesions were not identified before surgery. More importantly, 17% of the patients who underwent surgery because of the dysplasia only, showed cancer in the specimen. It is already clear that dysplasia detection in standard colonoscopy with random biopsies is very poor [Citation12]. More advanced techniques including dye-based chromoendoscopy and virtual chromoendoscopy such as narrow-band imaging have proven more efficient in detecting dysplasia and are recommended by the ECCO Guidelines [Citation4,Citation13]. In our endoscopy unit, the use of dye-based chromoendoscopy is increasing, but the majority of surveillance colonoscopies are still standard colonoscopies. The significance of dysplasia in UC has been under debate, with suggestions recently provided concerning the endoscopic management of lesions. However, the fact that the endoscopic recognition of dysplasia and even of cancer in UC is still far from optimal means that indications for surgery should perhaps not be altered.

The first meta-analysis estimating overall risk for CRC in UC patients was in 2001, from Eaden et al. [Citation14]. They reported the cumulative risk after UC diagnosis to be as high as 2% at 10 years, 8% at 20 years, and 18% at 30 years. They also stated that the incidence rate is higher in children than in adults. Later studies have shown lower CRC incidence rates. In 2014, Castaño-Milla et al. concluded in their meta-analysis that the overall risk has decreased steadily over the last six decades [Citation3], finding the overall CRC incidence rate to be only 1.58/1000py, and the cumulative risk to be 0.91% at 10 years, 4.07% at 20 years, and 4.55% at 30 years. This is still far higher than the incidence of sporadic CRC, which was approximately 0.6/1000py in 2017 in Finland. In a Finnish nationwide register study, Jussila et al. found an increased rate of colon cancers (SIR 1.81; 95% CI 1.46–2.21) and rectal cancers (SIR 1.76; 95% CI 1.35–2.25) in patients with ulcerative colitis, and the risk was highest among patients under age 45 [Citation15]. Naturally, there was an increased risk of CRC-related death, but the overall malignancy mortality rate was no higher than in the general population [Citation16]. In our study, the incidence of CRC among patients who underwent surgery for UC had remained unchanged over the last three decades.

Our study has several limitations. First, it is retrospective. Second, it includes surgical patients only, and for that reason, it may not represent well the stage IV cancers. Third, there has been multiple staging systems during the study period and diagnostic accuracy has developed during time. This might have caused stage migration but if so, the migration has most probably been downwards because of underdiagnosed lymph node and organ metastases. Finally, we had no control group of sporadic CRC patients.

The strengths are that the study is population-based and provides data extending for more than 28 years. Furthermore, Finland has free public healthcare services for everyone, and all surgery for ulcerative colitis in southern Finland is performed in our unit. We therefore assume that our data correlates well with reality regarding patients without metastatic disease (UICC stages I, II, and III).

Conclusions

The need for operative treatment of UC-associated colorectal cancer has remained stable over three decades in southern Finland. The 5-year CRC-specific survival in our patients with UC-associated CRC was 81.5%, no worse than was the 5-year CRC-specific survival of sporadic CRC. Synchronous dysplastic or even cancerous lesions were common, with a substantial proportion being evident only in examination of the surgical specimen. For this reason, we highly recommend surgical treatment over endoscopic management of high-grade dysplastic lesions and multifocal dysplasia.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Crohn B, Rosenberg H. The sigmoidoscopic picture of chronic ulcerative colitis (non-specific). Am J Med Sci. 1925;170:220–228.

- Yashiro M. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(44):16389–16397.

- Castaño-Milla C, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the declining risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(7):645–659.

- Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, et al.; European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(6):649–670.

- Qiu X, Ma J, Wang K, et al. Chemopreventive effects of 5-aminosalicylic acid on inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer and dysplasia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(1):1031–1045.

- Sebastian S, Hernández V, Myrelid P, et al. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: Results of the 3rd ECCO pathogenesis scientific workshop (I). J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(1):5–18.

- Watanabe T, Konishi T, Kishimoto J, et al. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer shows a poorer survival than sporadic colorectal cancer: a Nationwide Japanese Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:802–808.

- Delaunoit T, Limburg PJ, Goldberg RM, et al. Colorectal cancer prognosis among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(3):335–342.

- Leowardi C, Schneider M-L, Hinz U, et al. Prognosis of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal carcinoma compared to sporadic colorectal carcinoma: a matched pair analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(3):870–876.

- Brackmann S, Aamodt G, Andersen SN, et al. Widespread but not localized neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease worsens the prognosis of colorectal cancer. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16(3):474–481.

- Ording AG, Horváth-Puhó E, Erichsen R, et al. Five-year mortality in colorectal cancer patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(4):800–805.

- van den Broek FJC, Stokkers PCF, Reitsma JB, et al. Random biopsies taken during colonoscopic surveillance of patients with longstanding ulcerative colitis: low yield and absence of clinical consequences. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(5):715–722.

- Bessissow T, Dulai PS, Restellini S, et al. Comparison of endoscopic dysplasia detection techniques in patients with ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(12):2518–2526.

- Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48(4):526–535.

- Jussila A, Virta LJ, Pukkala E, et al. Malignancies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide register study in Finland. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(12):1405–1413.

- Jussila A, Virta LJ, Pukkala E, et al. Mortality and causes of death in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide register study in Finland. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(9):1088–1096.

References to a website

- Finnish cancer registry. https://cancerregistry.fi/statistics/cancer-statistics/. (accessed 11 July 2020).