Abstract

Objectives

Reports on quality-of-life (QoL) after bile duct injury (BDI) show conflicting results. The aim of this cohort study was to evaluate QoL stratified according to type of treatment.

Methods

QoL assessment using the SF-36 (36-item short form health survey) questionnaire. Patients with post-cholecystectomy BDI needing hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) were compared to all other treatments (BDI repair) and to patients without BDI at cholecystectomy (controls).

Results

Patients needing a HJ after BDI reported reduced long-term QoL irrespective of time for diagnosis and repair in both the physical (PCS; p < .001) and mental (MCS; p < .001) domain compared to both controls and patients with less severe BDI. QoL was comparable for BDI repair (n = 86) and controls (n = 192) in both PCS (p = .171) and MCS (p = .654). As a group, patients with BDI (n = 155) reported worse QoL than controls, in both the PCS (p < .001) and MCS (p = .012). Patients with a BDI detected intraoperatively (n = 124) reported better QoL than patients with a postoperative diagnosis. Patients with an immediate intraoperative repair (n = 99), including HJ, reported a better long-term QoL compared to patients subjected to a later procedure (n = 54).

Conclusions

Patients with postoperative diagnosis and patients with BDIs needing biliary reconstruction with HJ both reported reduced long-term QoL.

Introduction

Outcome after bile duct injury (BDI) repair in specialised referral centres is often reported as excellent in terms of postoperative complications and need for re-intervention [Citation1–7]. Early identification and referral to a hepatobiliary centre are advocated [Citation8]. Outcome in terms of quality-of-life (QoL) after BDI is less frequently reported in the literature, and the results in previous studies have been conflicting [Citation9–18].

A previous national cohort study from Sweden showed that patients suffering a minor BDI, defined as a lesion less than 5 mm, detected and repaired in conjunction with the cholecystectomy reported QoL comparable to uneventful cholecystectomy [Citation9]. Sarmiento and Hogan also reported no difference in long-term QoL after BDI when compared to uncomplicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy [Citation12,Citation16]. However, most QoL studies are from tertiary referral centres with an overrepresentation of severe injuries and failures after primary repair. Although the functional outcome is often reported as excellent, both mental and physical QoL may be impaired several years after repair [Citation10,Citation11,Citation13–15]. A meta-analysis from Landman et al. in 2013 stated that ‘there is a long-term detrimental effect of BDI on mental health-related QoL’ [Citation19]. A recent meta-analysis by Halle-Smith et al suggested ‘that HRQOL may potentially be related to the severity of the injury and whether patients undergo surgical repair’ [Citation18].

The aim of this national study was to evaluate QoL in patients after BDI needing biliary reconstruction with hepaticojejunostomy (HJ), compared to patients with less severe injuries and to a matched control group of patients subject to cholecystectomy without suffering from an iatrogenic BDI.

Methods

A Swedish QoL case–control cohort study reporting on 107 patients with BDI sustained during cholecystectomy from 2007 to 2011 has previously been published [Citation9]. That study included 17 HJs, excluded leakage from the cystic duct and liver bed, and the majority of BDIs (n = 63) were a lesion less than 5 mm. The study also included data on a control group subject to cholecystectomy without BDI (1:2) frequency-matched for, age, gender, ASA score, date of treatment (± 2 years), indication for cholecystectomy (uncomplicated gallstone disease versus complicated by cholecystitis, pancreatitis or biliary obstruction), planned or emergency procedure, and surgical technique (laparoscopic/converted/open procedure) [Citation9].

In a multicentre study by the European-African HepatoPancreatoBiliary Association (E-AHPBA), all consecutive patients operated with a HJ after BDI from January 2000 to June 2016 in Sweden were identified and outcome in terms of post-operative complications and patency was reported [Citation20].

By including all patients from Sweden in the E-AHPBA study [Citation20], a larger cohort of patients subject to HJ, from an extended time period, was achieved, and could be compared to previously published QoL data for all other forms of BDI repair, except HJ, and cholecystectomy without BDI (Controls) [Citation9].

QoL assessment

Original SF-36 scales have a range from 0 to 100 with varying means and standard deviations for the different subscales, which makes comparison difficult between subscales and different patient cohorts. It is recommended to use a norm-based score (NBS) in order to compare results more easily between studies [Citation21]. NBS transforms all the subscales to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10. The SF-36 NBS was calculated using Quality Metrics software, which compares with US norms based on randomly selected adults matched for age. US norms are widely used enabling comparison between studies and countries and are recommended and validated for international publications [Citation21].

SF-36v2 was licensed from Quality Metric, OPTUM Insight: SF36v2 License QUOTE QM047766 – OPTUM #CT154140 OP074018 OGS200.

The survey was performed by sending SF-36 forms to all patients subject to HJ after BDI 2000–2016 including patients that had not previously answered in the survey in 2013 (BDI 2007-2011). The questionnaires were distributed by mail to the participants in January 2019. Written reminders were sent by mail after approximately 4 weeks.

Ethics

Approval for the study was obtained from the Lund Regional Ethics Committee, Sweden (Dnr 2017/279) and all participants returned a signed approval form before inclusion.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. Initial group comparisons were made using the Mann–Whitney test, Fisher’s exact test and Chi2 test when appropriate. Student t-test or Mann–Whitney U were used for comparison of SF-36 data, and the latter test was used when n < 20. Since SF-36 data are ordinal, non-parametric analyses were performed primarily. The QoL data for bile duct injuries were further stratified for analysis according to the time of diagnosis/repair and type of repair. For pair-wise comparison between groups ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests were applied. A p < .05 was considered significant.

Results

In Sweden, a total of 122 HJs after BDI were performed from 2000 to 2016 [Citation20] and were compared to 144 BDIs from 2007 to 2011 [Citation9] subject to all other forms of repair (BDI repair) including drainage, suture (with or without T-tube) and/or endoscopic treatment. Demographic data for these two groups compared to the control group with uneventful cholecystectomy [Citation9] are displayed in . There was no difference in age or sex between groups, at the time of cholecystectomy. The injuries subsequently needing a HJ for reconstruction were to a lesser extent detected intraoperatively as compared to less severe injuries, . Patients with a BDI needing a HJ had a longer follow-up at the time of the survey, but there was no difference in age between responders in the different groups. For patients receiving a HJ, 12 patients were reconstructed at the index operation, and median time for all biliary reconstructions was 5 (1–90) days after cholecystectomy.

Table 1. Patients subject to; cholecystectomy without bile duct injury (Controls), with a BDI subject to drainage, suture with or without T-tube and/or endoscopic treatment (BDI repair) and a BDI needing biliary reconstruction with hepaticojejunostomy (HJ).

Table 2. Responders to the quality of life document SF-36.

Baseline characteristics for the responders to the survey are displayed in . Median age of all patients responding to the survey was 61 (50–72) years and the follow-up was longer for patients with a HJ, median 8 (5–13) years after the injury. A majority of patients (63/86) subjected to BDI repair and responding to the QoL survey had a lesion less than 5 mm of the bile duct (Strasberg type D or Hannover grade C1), and none had a complete transection of the bile duct. The severity of injury in the group subjected to HJ was not specifically graded, in part due to the difficulty to determine exact injury grade retrospectively, especially in patients with postoperative diagnosis.

Overall the QoL reported was good with physical and mental component scores (PCS: 49.4, SD 9.95; MCS 50.0, SD 10.9), and mean SF-36 summary scores for the three groups, stratified for intra- or postoperative diagnosis, are displayed in .

Table 3. Mean SF-36 summary scores for patients stratified into the following groups; subject to cholecystectomy without bile duct injury (controls), all bile duct injuries (BDI), patients with a BDI subject to drainage, suture with or without T-tube and/or endoscopic treatment (BDI repair), patients with a BDI needing biliary reconstruction with hepaticojejunostomy (HJ); all BDIs stratified according to time of detection of the injury (intraoperative or postoperative diagnosis).

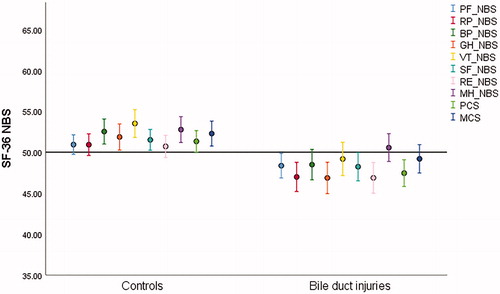

When comparing the whole cohort of patients with a BDI (n = 155) to patients with cholecystectomy without BDI (n = 192), the patients with a BDI reported worse QoL in both the physical and mental domain than the controls (PCS; p < .001 and MCS; p = .012) ().

Figure 1. SF-36 norm-based scores (SF-36 NBS). Controls (cholecystectomy without bile duct injury) (n = 192); BDI (bile duct injury) (n = 155). Mean 50, SD 10, error bars with 95% CI. Subscales presented in the following order: PF (physical function); RP (role physical); BP (bodily pain); GH (general health); VT (vitality); SF (social function); RE (role emotional); MH (mental health); PCS (physical composite score); MCS (mental composite score).

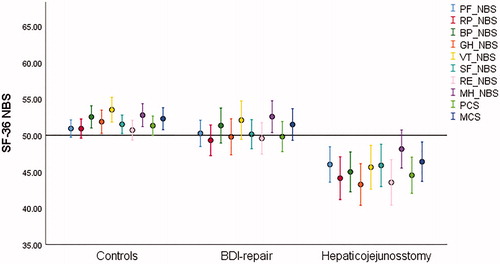

QoL was comparable for controls (n = 192) and patients with less severe BDIs (BDI repair; n = 86), that is patients with a BDI subject to drainage, suture with or without T-tube and/or endoscopic treatment not needing a biliary reconstruction (PCS; p = .171 and MCS; p = .654). Long-term QoL in patients needing a bilioenteric anastomosis (HJ) (n = 69) was worse than in patients subject to all other forms of repair (BDI repair) (n = 86) (PCS; p = .002 and MCS; p = .003) ().

Figure 2. SF-36 norm-based scores (SF-36 NBS). Controls (cholecystectomy without bile duct injury) (n = 192); BDI repair (BDI subject to drainage, suture with or without t-tube and endoscopy) (n = 86); Hepaticojejunostomy (n = 69). Mean 50, SD 10, error bars with 95% CI. Subscales presented in the following order: PF (physical function); RP (role physical); BP (bodily pain); GH (general health); VT (vitality); SF (social function); RE (role emotional); MH (mental health); PCS (Physical Composite Score); MCS (Mental Composite Score).

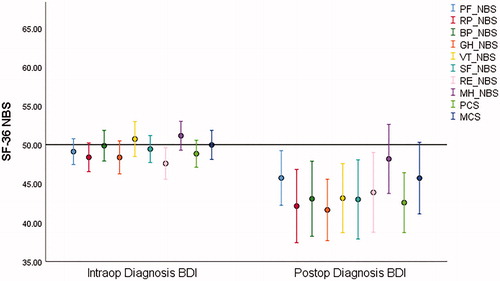

Patients who had their BDI detected intraoperatively (n = 124) reported better QoL than patients with a postoperative diagnosis but reported a lower physical QoL than controls (n = 192), (PCS; p = .018 and MCS; p = .072), . When comparing patients with intra- and postoperative diagnosis of BDI, there was a difference in physical component score (PCS; p = .003 and MCS; p = .068), . Notably 24 out of 30 patients with postoperative diagnosis had a BDI that needed a biliary reconstruction with a HJ. For patients with HJ (n = 69), there was no difference in long-term QoL for timing of diagnosis (intra- or postoperative diagnosis) of BDI (PCS: p = .375; MCS: p = .414).

Figure 3. SF-36 norm-based scores (SF-36 NBS). Intraoperative diagnosis (n = 124), Postoperative diagnosis (n = 30). Mean 50, SD 10, error bars with 95% CI. Subscales presented in the following order: PF (physical function); RP (role physical); BP (bodily pain); GH (general health); VT (vitality); SF (Social Function); RE (role emotional); MH (mental health); PCS (Physical Composite Score); MCS (Mental Composite Score).

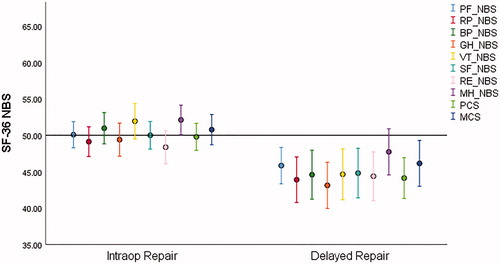

Patients with an immediate intraoperative repair (n = 99), including HJ, reported a better long-term QoL compared to patients subjected to a later procedure (n = 54), either due to postoperative diagnosis (n = 30) or delayed surgery and/or referral (n = 24), (PCS; p = .002 and MCS; p = .011), . Immediate intraoperative repair (n = 99) included 12 HJs, 51 suture(s) over T-tube, 33 suture repairs, 2 endoscopic procedures, and one laparotomy with drain.

Figure 4. SF-36 norm-based scores (SF-36 NBS). Immediate intraoperative repair (n = 99), Delayed/later repair (n = 54). Mean 50, SD 10, error bars with 95% CI. Sub-scales presented in the following order: PF (physical function); RP (role physical); BP (bodily pain); GH (general health); VT (vitality); SF (social function); RE (role emotional); MH (mental health); PCS (physical composite Score); MCS (Mental Composite Score).

Sensitivity analyses

Since SF-36 data are ordinal, non-parametric analyses were performed primarily and presented in Results. When treating PCS and MCS as continuous variables, and performing Students t-test, the same p-values were calculated as when Mann–Whitney U was used and histograms confirmed sufficiently normally distributed variables.

Multivariable linear regression analysis

When adjusting for age, sex and follow-up there was still a significant difference between BDI repair and HJ in QoL, PCS estimate −4.7, p = .010 (OR −2.605; 95% CI −1.140 to −8.307) and MCS estimate −5.5, p = .004 (OR −2.907; 95% CI −1.758 to −9.223). Scatterplots on regression standardised residuals and predicted values were acceptable.

Discussion

This nationwide study shows that BDI resulted in reduced long-term QoL, evaluated with SF-36, for patients reconstructed with a HJ compared to patients treated with cholecystectomy without BDI. In addition, HJ resulted in a reduction in QoL compared to patients with BDI treated with drainage, sutures and/or endoscopy. A similar reduction in physical QoL (PCS) as in the present study, but without difference in the mental domain (MCS), was found in the study by Booij et al. including not only HJ but a majority of injuries referred to a tertiary hepatobiliary centre treated by endoscopic and/or percutaneous means [Citation17]. Most previous studies have focused on classification of the BDI and its impact on the outcome. The impact on QoL by type of repair, and HJ alone, has previously been investigated to a little extent. A recent study by Otto et al. included 236 patients reconstructed with HJ, but the comparison is difficult since a majority of the included patients had their primary repair at a local hospital and 59 patients were referred first after developing an anastomotic stricture [Citation22]. In a recent multicentre study on HJ after BDI, the long-term re-intervention rate was 11% [Citation20]. Interventions after HJ have been shown to further decrease QoL [Citation23]. In addition, the duration of treatment is of importance and long treatment periods have been described to be associated with reduced QoL [Citation10].

The clinical relevance of the reduction in QoL found in the present study is somewhat difficult to assess. The concept of minimally clinically important difference (MCID) of the SF-36 PCS score has been elaborated for, e g. hip and knee replacement, with a MCID of 3–21 [Citation24], rheumatoid arthritis (MCID = 7) [Citation25], asthma and heart disease (MCID = 10) [Citation26], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (MCID = 8) [Citation26]. For MCS, a MCID of 5 was found for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and comorbid anxiety [Citation27]. The changes in PCS and MCS between patients reconstructed with HJ compared to control patients were 6.6 and 5.8, respectively, is therefore in the lower range of what is considered MCID.

The length of follow-up between groups differed in this study, being significantly longer for patients with HJ, but the age of the responders to the survey did not differ between groups. Age has importance for patient QoL, primarily displayed as a decreasing PCS with increasing age [Citation22,Citation28,Citation29]. The age of patients at the time of the QoL survey in the present study was 61 (50-72) years, which can be compared to 50 years in the study by Booij et al. [Citation17]. Accordingly, comparing the PCS for the control groups in these studies, a lower PCS was found in the present study (51 versus 54). However, the control group reported higher QoL than, for example, the reference values for the Norwegian population, (PCS 47.01, SD 10.24; MCS 50.48, SD 9.61) [Citation29].

Comparable long-term QoL was found between controls and patients with less complex repairs (BDI repair; drainage, sutures and/or endoscopy). If the BDI was diagnosed and treated immediately at the index cholecystectomy patients reported QoL better than if the injury was treated at later stage, either because of later diagnosis and/or referral to a tertiary hepatobiliary centre. A recent meta-analysis concluded that published studies on QoL after BDI are still conflicting with half showing worse QoL and half showing similar QoL [Citation18]. Two factors potentially related to reduced QoL were identified: major BDI and nonsurgical treatment. The former is in line with the present study showing the need for HJ being associated with worse long-term QoL. Otto et al. reported satisfactory QoL after definitive biliary reconstruction in 199 patients, but that patients diagnosed with post-cholecystectomy inflammatory complications had worse outcome [Citation22].

Post-operative detection is correlated to more severe BDI, most likely due to confirmation bias during cholecystectomy (the surgeon is convinced of operating on the cystic duct during the whole procedure until proven wrong post-operatively). The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of biliary reconstruction for post-cholecystectomy BDI, not to evaluate QoL by classification of severity of the BDI. QoL after HJ is probably influenced by long-term complications. The biliary stricture rate, defined as the need for biliary re-intervention more than 90 days after reconstruction with HJ, was 20% in the Swedish cohort presented in Rystedt et al. [Citation20]. However, no data on long-term complications for patients with BDI repair (less severe injuries than those repaired with HJ) was included in the present study, making it difficult to assess the importance of long-term complications on QoL.

The strengths of this study are that it is nationwide and includes a large number of severe BDIs needing biliary reconstruction and the long follow-up time. The response rate is acceptable and comparable to previous publications [Citation11,Citation13,Citation15]. A weakness of the study is that QoL was measured only at one occasion and several years after the cholecystectomy and the BDI. Neither was cystic duct leakage included in the analysis though previous studies have shown poor QoL during and after treatment for this type of injury [Citation10].

In conclusion, this nationwide cohort study showed a reduction in both physical QoL and mental QoL for patients suffering a severe BDI during cholecystectomy, which required a biliary reconstruction with a HJ, as compared to patients without BDI as well as to patients with less severe BDI.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Sicklick JK, Camp MS, Lillemoe KD, et al. Surgical management of bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: perioperative results in 200 patients. Ann Surg. 2005;241(5):786–792.

- de Reuver PR, Grossmann I, Busch OR, et al. Referral pattern and timing of repair are risk factors for complications after reconstructive surgery for bile duct injury. Ann Surg. 2007;245:763–770.

- Dominguez-Rosado I, Sanford DE, Liu J, et al. Timing of surgical repair after bile duct injury impacts postoperative complications but not anastomotic patency. Ann Surg. 2016;264:544–553.

- Perera MT, Silva MA, Hegab B, et al. Specialist early and immediate repair of post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy bile duct injuries is associated with an improved long-term outcome. Ann Surg. 2011;253:553–560.

- Thomson BN, Parks RW, Madhavan KK, et al. Early specialist repair of biliary injury. Br J Surg. 2006;93(2):216–220.

- Connor S, Garden OJ. Bile duct injury in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93(2):158–168.

- Bektas H, Schrem H, Winny M, et al. Surgical treatment and outcome of iatrogenic bile duct lesions after cholecystectomy and the impact of different clinical classification systems. Br J Surg. 2007;94(9):1119–1127.

- Khadra H, Johnson H, Crowther J, et al. Bile duct injury repairs: progressive outcomes in a tertiary referral center. Surgery. 2019;166(4):698–702.

- Rystedt JM, Montgomery AK. Quality-of-life after bile duct injury: intraoperative detection is crucial. A national case-control study. HPB (Oxford). 2016;18(12):1010–1016.

- Boerma D, Rauws EA, Keulemans YC, et al. Impaired quality of life 5 years after bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective analysis. Ann Surg. 2001;234(6):750–757.

- Melton GB, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, et al. Major bile duct injuries associated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy: effect of surgical repair on quality of life. Ann Surg. 2002;235(6):888–895.

- Sarmiento JM, Farnell MB, Nagorney DM, et al. Quality-of-life assessment of surgical reconstruction after laparoscopic cholecystectomy-induced bile duct injuries: what happens at 5 years and beyond? Arch Surg. 2004;139(5):483–488.

- Moore DE, Feurer ID, Holzman MD, et al. Long-term detrimental effect of bile duct injury on health-related quality of life. Arch Surg. 2004;139(5):476–481.

- de Reuver PR, Sprangers MA, Gouma DJ. Quality of life in bile duct injury patients. Ann Surg. 2007;246(1):161–163.

- de Reuver PR, Sprangers MA, Rauws EA, et al. Impact of bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy on quality of life: a longitudinal study after multidisciplinary treatment. Endoscopy. 2008;40(08):637–643.

- Hogan AM, Hoti E, Winter DC, et al. Quality of life after iatrogenic bile duct injury: a case control study. Ann Surg. 2009;249(2):292–295.

- Booij KAC, de Reuver PR, van Dieren S, et al. Long-term impact of bile duct injury on morbidity, mortality, quality of life, and work related limitations. Ann Surg. 2018;268(1):143–150.

- Halle-Smith JM, Hodson J, Stevens L, et al. Does non-operative management of iatrogenic bile duct injury result in impaired quality of life? A systematic review. Surgeon. 2020;18(2):113–121.

- Landman MP, Feurer ID, Moore DE, et al. The long-term effect of bile duct injuries on health-related quality of life: a meta-analysis. HPB (Oxford). 2013;15(4):252–259.

- An E-AHPBA Collaborative Research Study. Post cholecystectomy bile duct injury: early, intermediate or late repair with hepaticojejunostomy - an E-AHPBA multi-center study. HPB (Oxford). 2019;21:1641–1647.

- Ware JE, Jr., Gandek B, Kosinski M, et al. The equivalence of SF-36 summary health scores estimated using standard and country-specific algorithms in 10 countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):1167–1170.

- Otto W, Sierdzinski J, Smaga J, et al. Long-term effects and quality of life following definitive bile duct reconstruction. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12684.

- AbdelRafee A, El-Shobari M, Askar W, et al. Long-term follow-up of 120 patients after hepaticojejunostomy for treatment of post-cholecystectomy bile duct injuries: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;18:205–210.

- Keurentjes JC, Van Tol FR, Fiocco M, et al. Minimal clinically important differences in health-related quality of life after total hip or knee replacement: a systematic review. Bone Joint Res. 2012;1(5):71–77.

- Ward MM, Guthrie LC, Alba MI. Clinically important changes in short form 36 health survey scales for use in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials: the impact of low responsiveness. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66(12):1783–1789.

- Wyrwich KW, Tierney WM, Babu AN, et al. A comparison of clinically important differences in health-related quality of life for patients with chronic lung disease, asthma, or heart disease. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(2):577–591.

- Kroenke K, Baye F, Lourens SG. Comparative responsiveness and minimally important difference of common anxiety measures. Med Care. 2019;57(11):890–897.

- Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Wright L. Short form 36 (SF36) health survey questionnaire: normative data for adults of working age. BMJ. 1993;306(6890):1437–1440.

- Garratt AM, Stavem K. Measurement properties and normative data for the Norwegian SF-36: results from a general population survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):51.