Abstract

Objectives

Surgically altered anatomy complicates endoscopical procedures of pancreatobiliary tree. Biliary or hepaticojejunal anastomosis strictures have been managed using percutaneous transhepatic or double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) techniques with multiple plastic stents, or fully covered self-expandable metal stents. We report the first seven cases with surgically altered anatomy treated with biodegradable stents with DBE.

Materials and methods

Seven cases with altered anatomy, all with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (HJ), were treated for HJ anastomosis strictures (3 cases) and intrahepatic biliary stricture (4 cases). Fujifilm DB enteroscope with a 200 cm long and 3.2 mm wide working channel was used. Balloon dilatations were first performed and then 1–3 biodegradable stents were deployed with a pusher over a guidewire.

Results

Two patients had HJ due to liver resections, one due to biliary injury in cholecystectomy and four due to liver transplantation because of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Median duration of the procedures was 56 min. Deployment of the stents took less than 20 min per patient. There were no stent or cholangiography related adverse events, but one patient required endotracheal intubation for nose bleeding caused by the placement of nasopharyngeal tube. Two PSC patients had recurrent cholangitis in the follow up. There was one stent migration in 90 day follow up. With all the HJ anastomotic strictures resolution of strictures seemed to be achieved.

Conclusions

Treatment of biliary or anastomosis strictures in altered anatomy is complex and time consuming. The biodegradable stent, which can be passed through working channel of a long enteroscope, seems promising in the treatment of these strictures. The benefit is that no stent removal is needed.

Introduction

Endoscopic management of pancreaticobiliary duct problems is technically demanding and time consuming in patients with surgically altered anatomy. The length of duodenoscope is usually insufficient for the traditional endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures. Therefore, biliary or hepaticojejunostomy (HJ) anastomotic strictures have been managed by using percutaneous transhepatic (PT) or double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) techniques, or surgery. In recent years, DBE-assisted endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) has shown to be efficient and safe treatment method, and is gaining popularity [Citation1,Citation2]. However, there are still limitations with the use of DBE: the length of the bowel passage and adhesions can cause inability to reach the papilla or pancreaticobiliary anastomosis, and cannulation is challenging with the lack of appropriate tools for DBE. In bariatric surgery patients with roux-en-Y gastric bypass laparoscopy-assisted ERCP has been successfully used to overcome these challenges. With this technique a standard duodenoscope is advanced through a gastrostomy into the excluded stomach and duodenum to access the papilla allowing the use of standard accessories [Citation3].

In conventional ERC, benign biliary strictures (BBS) have been successfully treated with multiple plastic stents or fully covered self-expandable metallic stents (fcSEMS) [Citation4–6]. In few studies, also biodegradable biliary stents have reported to be feasible and safe in the treatment of BBSs [Citation7–9]. In DBE-ERC single or multiple plastic stents have been used [Citation2,Citation10] and we have used fcSEMS [Citation11], in the treatment of BBSs and anastomotic strictures. Currently, there are no case reports about using biodegradable stents in DBE-ERC.

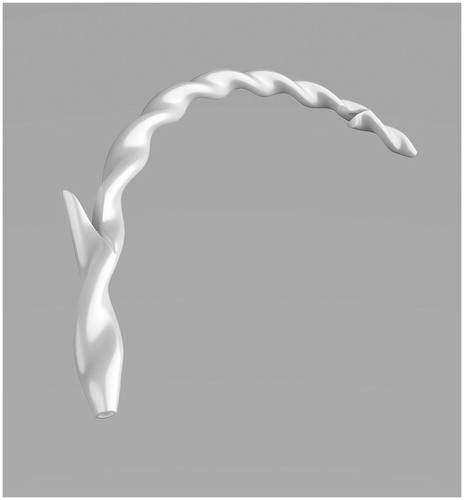

Archimedes stent (amg International GmbH, Winsen, Germany) is a commercially available biodegradable biliary and pancreatic stent, which has a helical structure allowing the bile flow on the outer extremity of the stent while supporting the opening of the lumen (). The stent has anatomical shape, tapered tip, and proximal and distal flaps. There are three types of stents varying from the degradation profile: fast (12 days), medium (25 days) and slow (12 weeks) degrading stent, and there are several diameter and length options available.

Figure 1. Archimedes stent (amg International GmbH, Winsen, Germany) has a helical structure allowing the bile flow on the outer extremity of the stent while supporting the opening of the lumen. The stent has anatomical shape, tapered tip, and proximal and distal flaps.

With the use of plastic stents and fcSEMSs there is requirement for repeat conventional or DBE-ERC for stent removal. The benefit of biodegradable stents is that stent removal can be avoided. Here we report the first seven cases with surgically altered anatomy treated with biodegradable Archimedes stents with DBE-ERC in Helsinki University Hospital.

Materials and methods

The research was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Helsinki University. The patient characteristics are shown in and the procedural characteristics in . Seven nonconsecutive patients with surgically altered anatomy were treated with slow degrading Archimedes stents between September 2018 and May 2019. All the patients had Roux-en-Y HJ. There were three cases with anastomotic strictures and four cases with intrahepatic strictures. The median length of procedures was 56 min, range 28–119 min.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Table 2. Procedural characteristics.

Fujifilm DB enteroscope, EN-580T, with a 200 cm long and 3.2 mm wide working channel (Fujifilm Corp. Tokyo, Japan) was used. In all cases, there was a 145 cm long and 13.2 mm wide TS-13140 overtube with a transparent hood attached to the tip of the scope. All procedures were performed using CO2-insufflation, with the patient in prone position, under conscious sedation controlled by an anesthesiologist and a nurse. Five patients received antibiotic prophylaxis and two patients (numbers 1 and 7) had ongoing antibiotic therapy during the procedures.

All stents were placed by experienced endoscopists. The largest possible diameter of slow degrading stent to be used with DB enteroscope is 2.6 mm which equals to 8 Fr. The length of the stent was determined according to the length and location of the stricture, and the number of the stents according to the diameter of the stricture. For HJ anastomoses strictures 8–12 mm balloon dilations (Boston scientific CRE TM Wireguided Dilatation catheter 290 cm, Natick, MA, USA) were first performed, and then 2–3 biodegradable stents (Archimedes, slow degrading, diameter 2.6 mm, length 6–8 cm) were deployed with a 7 Fr pusher (Cook Medical) over a guidewire (FTE Wildcat, 0.035 inch, length 650 cm; pk endoskopie GmbH, Hannover, Germany). For intrahepatic strictures 6–8 mm balloon dilations were performed and one Archimedes stent (slow degrading, diameter 2.6 mm, length 6–8 cm) placed with the pusher.

Technical success was defined as ability to reach the HJ anastomosis, and accurate deployment and positioning the Archimedes stent. Clinical success was defined as absence of cholangitis and/or no need to other interventions or procedures because of recurrent stricture or stent migration.

Patients

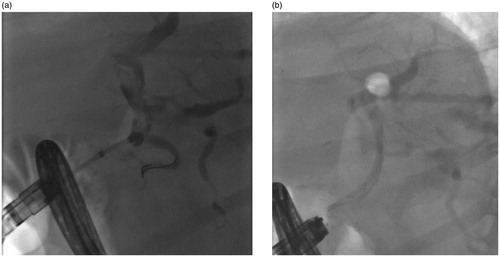

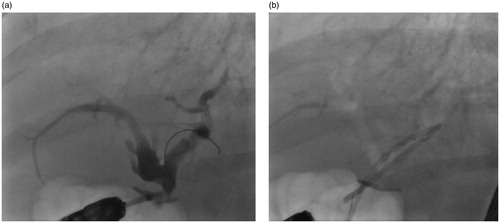

The first patient, 56-year-old male with acute lymphocyte leukemia, had a liver resection of segments 5–8 and HJ with segments 2–3 due to echinococcal cysts and strictures in April 2004. In the beginning of 2018 he suffered from recurrent cholangitis and in magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) anastomotic stricture and proximal stone were suspected. In September 2018, first a conventional ERC via the normal route was done with normal findings, and then 10 days after a DBE-ERC via the HJ route with findings of ongoing cholangitis, stones and an anastomotic stricture (). A 12 mm balloon dilation and stone removal were performed and two Archimedes stents (diameter 2.6 mm and lengths 6 cm) deployed ().

Figure 2. The fluoroscopy views of patient (number 1) with hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic stricture (a) before and (b) after stenting with Archimedes stents.

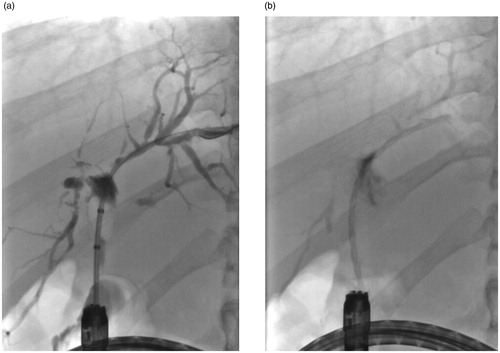

The second patient, 49-year-old female with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), had a liver transplantation with HJ in 2002 and retransplantation in January 2012. She had recurrent cholangitis, and in March 2018 a DBE-ERC with dilation of the right site intrahepatic stricture was performed. Afterwards, a percutaneous transhepatic (PT) drain was put due to a left site stricture. In May 2018, second DBE-ERC with dilation and stenting (8.5 Fr plastic stent) of the left site intrahepatic stricture and removing of the PT drain was done. In October 2018, a planned DBE-ERC for retrieval the plastic stent was performed. There was still a stricture in the left site intrahepatic bile ducts () and a 6 mm balloon dilation was done, and one Archimedes stent (diameter 2.6 mm and length 8 cm) deployed ().

Figure 3. The fluoroscopy views of patient (number 2) with left site intrahepatic stricture (a) before and (b) after stenting with Archimedes stent.

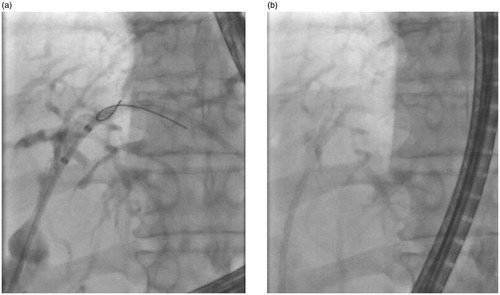

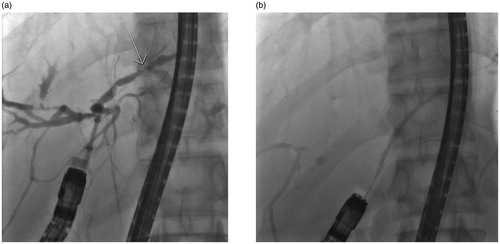

The third patient, 55-year-old female with biliary stones, had laparoscopic cholecystectomy and a biliary injury in 2008. First, a choledochojejunostomy was performed, but because of anastomotic stricture a HJ was done in January 2010. In the beginning of 2018, she had cholangitis and in MRCP a biliary stone and anastomotic stricture were seen. In April 2018, a DBE-ERC with dilation of anastomosis and stone removal was performed. There was still recurrent cholangitis and in October 2018s DBE-ERC was done. An anastomotic stricture was found (), and a 10 mm dilation and stenting with three Archimedes stents (diameter 2.6 mm and lengths 2 × 8 cm, 6 cm) were performed ( and ).

Figure 4. The fluoroscopy view of patient with hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic stricture (number 3).

Figure 5. The fluoroscopy view of Archimedes stents of patient with hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic stricture (number 3) showing good visibility of the stents.

Figure 6. The endoscopy view of Archimedes stents of patient with hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic stricture (number 3).

The fourth patient, 72-year-old female with cholangiocarcinoma, had a liver resection with HJ in June 2013. In May 2014, a DBE-ERC with anastomotic dilation was performed. After one year, she started to suffer from recurrent cholangitis and in MRCP a new anastomotic stricture was suspected. In October 2018, a DBE-ERC with 8 mm dilation of the stricture was done, and two Archimedes stents (diameter 2.6 mm and lengths 6 cm) deployed ().

Figure 7. The fluoroscopy views of patient (number 4) with hepaticojejunostomy anastomotic stricture (a) before and (b) after stenting with Archimedes stents.

The fifth patient, a 26-year-old female with ulcerative colitis (UC) and PSC – autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) overlap syndrome, had a liver transplantation with HJ in December 2011. In the beginning of 2018, liver enzymes were found elevated and patient suffered from itching. A DBE-ERC with dilation of a left site intrahepatic stricture was performed in March 2018. A right site stricture was also suspected in MRCP, but that could not be reached or dilated. In December 2018, a new rise in liver enzymes was noted and a DBE-ERC with 8 mm dilation of the left site intrahepatic stricture was performed, and one Archimedes stent (diameter 2.6 mm, length 8 cm) deployed ().

Figure 8. The fluoroscopy views of patient (number 5) with left site intrahepatic stricture (a) before and (b) after stenting with Archimedes stent.

The sixth patient, 30-year-old male with UC and PSC, had a liver transplantation with HJ in August 2014. In 2018, elevated liver enzymes were found and in MRCP a left site intrahepatic stricture was suspected. In October 2018, a DBE-ERC with dilation of the left site intrahepatic stricture was performed. There was a new elevation in liver enzymes and in March 2019s DBE-ERC with 7 mm dilation of the left site intrahepatic stricture was done, and one Archimedes stent (diameter 2.6 mm and length 6 cm) deployed ().

Figure 9. The fluoroscopy views of patient (number 6) with left site intrahepatic stricture (a) before and (b) after stenting with Archimedes stent.

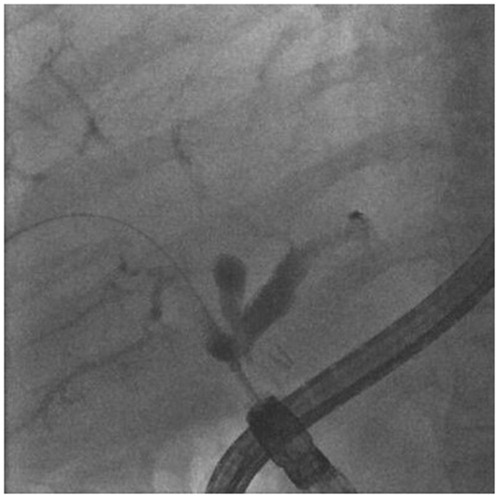

The seventh patient, 34-year-old female with UC and PSC, had a liver transplantation with HJ in September 2015. She suffered from recurrent strictures and cholangitis, and three DBE-ERCs were performed between July 2017 and February 2019. In the first one, a right site intrahepatic stricture was dilated, in the second one a left site intrahepatic stricture and anastomosis were dilated, and in the third one a right site intrahepatic stricture and anastomosis were dilated. After the last DBE-ERC a PT drain was put in the right site bile ducts, and a retransplatation was planned. Patient had discomfort with the PT drain and in May 2019 a new DBE-ERC with 6 mm dilation of the right site intrahepatic stricture () and stenting with one Archimedes stent (diameter 2.6 mm and length 6 cm) was done. The PT drain was also removed.

Results

All the DBE-ERCs succeeded; the HJ anastomoses were reached and the Archimedes stents were easily deployed. One patient (number 6) had a laryngeal spasm during the procedure, and a nasopharyngeal tube was placed to help the breathing. That caused nose bleeding and desaturation, and the patient had to be intubated. Six patients were discharged within 48 h of the procedure, but one patient with ongoing cholangitis (number 1) needed to stay 5 days in hospital receiving antibiotics. There were no stent or cholangiography related adverse events. The median preprocedural bilirubin level was 23 umol/l, range 5–42 umol/l and alkaline phosphatase level 192 U/l, range 118–335 U/l; and the postprocedural (after 1 week) 21 umol/l, range 7–31 umol/l and 196 U/l, range 131–340 U/l, respectively. The follow up data are shown in .

Table 3. Follow up data.

30 Day follow up

The patient (number 5) with PSC-AIH overlap syndrome and liver transplantation had mild rise in liver enzymes after 1 week of discharge. An ultrasound was done with normal findings, and the liver enzymes decreased spontaneously in few days.

The patient (number 7) with recurrent strictures and cholangitis did well 2 weeks after discharge. After that, she suffered from recurrent cholangitis again and needed treatment with antibiotics. However, no other procedures were needed, but the liver retransplantation was planned.

All the other patients had no adverse events after discharging during the 30 days follow up.

90 Day follow up

The patient (number 2) with PSC and liver retransplantation had cholangitis and a new DBE-ERC was performed in January 2019. In that procedure, the Archimedes stent was found migrated in the bowel beside the HJ anastomosis. Interestingly, the stent had not degraded. There was still an intrahepatic stricture in the left site, and a plastic stent (8.5 Fr pigtail) was deployed. The Archimedes stent was retrieved from the bowel.

The patient (number 3) with biliary injury because of laparoscopic cholecystectomy had upper abdominal pain attacks after 2.5 months of discharging. MRCP was done with normal findings and a new DBE-ERC in April 2019 with normal findings. The etiology of pain stayed unsolved.

The patient (number 7) with recurrent strictures and cholangitis was treated with antibiotics and a liver retransplantation was done in the beginning of July 2019.

All the other patients did well during the 90 days follow up.

Overall, the technical success was 100% and the clinical success 71% (5/7 cases) in the 90 day follow up.

Total follow up (until end of June 2020)

The median total follow up was 599 days, range 418–648 days. The patient (number 2) with PSC and liver retransplantation had recurrent cholangitis, and a second DBE-ERC after discharging was done in April 2019. The plastic stent was found migrated beside the HJ anastomosis and no other stent was placed. A thought of third liver transplantation was woken up. However, the patient had a gastric bypass operation because of morbid obesity in May 2019, and did well after that, the liver transplantation thought has been postponed.

All the other patients have been well afterwards.

Discussion

Here we report the first seven patients with surgically altered anatomy treated successfully with biodegradable Archimedes stents with DBE-ERC. The stents were easily and fast deployed (less than 20 min), and the median procedural length was decent (56 min). All the patients had Roux-en-Y HJ, and there were three cases with anastomotic strictures and four with intrahepatic strictures. Resolution of the stricture was achieved with all anastomotic strictures (follow up 599–648 days). One patient with anastomotic stricture had a DBE-ERC in 90 day follow up, but this was due to abdominal pain attacks, and no recurrent stricture was found. The liver transplantation patients with intrahepatic strictures were more difficult to treat, and two (one patient had only elevated liver enzymes for a short period) of these patients suffered from recurrent cholangitis and needed more procedures: repeated DBE-ERC because of stent migration and liver retransplantation. However, the liver retransplantation was planned even before the DBE-ERC due to recurrent PSC, and the patient could wait that procedure without uncomfortable PT drain because of the Archimedes stent.

There were no stent or cholangiography related adverse events e.g., perforations or bleedings, but one patient required endotracheal intubation for nose bleeding caused by the placement of nasopharyngeal tube. The Archimedes stents were easily deployed through the long working channel (200 cm) of the DBE, and the visibility in fluoroscopy was good (). There are three types of stents varying from the degradation profile (fast, medium and slow degrading) available, which enables the use for different indications. There are also wide selection of diameters and lengths of these stents. The only deficiency seems to be quite short expiration time. In a pilot study of 53 patients with conventional ERCP these stents have found to be safe and efficacious in the treatment of biliary and pancreatic duct obstructions [Citation9].

In our cases, one patient had stent migration in 90 day follow up and needed second DBE-ERC with stenting (8.5 Fr plastic pigtail stent). However, this plastic stent migrated also in the follow up, so the migration problem could be more a biliary duct related than stent related. Interestingly, the migrated Archimedes stent had not degraded, and was found intact in the bowel after 12 weeks. With biodegradable stents some concern has been expressed about the stent degradation and potential foreign body reaction causing adverse hyperplasia, stone formation or restricturing of the duct, but the small human studies with polydioxanone stents have shown promising results about the safety [Citation8]. Anderloni et al. has published a pilot study of Archimedes stents and their degradation times. In that study, the degradation time of slow degrading stents was controlled by abdominal radiograph in two time points, at 3 and 6 months, respectively. At 3 months, 32 of 35 (91.4%) slow degrading stents were found partially degraded, and at 6 months a complete degradation of the stents was found. Migration occurred in 3 of 35 (14.3%) of the stents placed for cholangitis. It was concluded that stent degradation time is reliable and consistent with expected times according to the manufacturer’s information [Citation12]. We did not follow up the patients with MRCP or abdominal radiographs after discharging, so we can only assume that there were no other stent degrading related problems because no other procedures were needed.

The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) clinical guideline recommends for the treatment of BBSs temporary insertion of multiple plastic stents with the maximum number of stents possible every 3–4 months for a total duration of 12 months, or of a fcSEMS insertion of an 8-10 mm diameter stent for a dwell stenting period of 6 months. For the treatment of benign anastomotic biliary strictures following orthotopic liver transplantation ESGE suggests temporary insertion of multiple plastic stents pending further evidence about fcSEMSs [Citation5]. For the treatment of HJ anastomotic strictures and BBSs in patients with surgically altered anatomy the published data of different stent types and stenting times are scarce. In one Japanese retrospective study of 91 patients with HJ anastomotic stricture a balloon dilatation was performed as a first-line treatment and plastic stents were placed for refractory cases. The resolution of an anastomotic stricture was achieved overall in 70 patients (76.9%) with a median follow up time of 30.9 months, and in stented patients with the median duration of stent placement of 5.6 months [Citation10].

In our patients with HJ anastomotic strictures (n = 3), resolution of the stricture seemed to be achieved in all cases treated with the Archimedes stents. With the slow degrading stents the stated degradation time is 11–12 weeks which equals to 3 months. In our HJ anastomotic stricture cases, all patients but one (number 1) had gone through balloon dilatation (numbers 3 and 4) before the procedure with balloon dilatation and Archimedes stent placement. So, the overall treatment method was similar to that used in the Japanese study [Citation10] and the treatment period longer than 3 months. Our group has previously reported the first three cases with HJ anastomotic strictures treated successfully with fcSEMSs with stenting period varying between 3 and 12 months [Citation11]. However, therapy with plastic stents or fcSEMSs requires second DBE-ERC for stent removal. The main benefit with biodegradable stents is that there is no need for stent removal, which saves the patient from repeated procedures, saves time and costs, and decreases potential procedure related adverse events.

The Archimedes stents were easily deployed through the long working channel (200 cm) of DBE. However, use of currently available ERCP devices is limited because of the long working channel. To overcome this, a short DBE with working channel length of 152 cm has successfully been used in DBE-ERC procedures [Citation2]. This short DBE enables the use of conventional ERCP tools making the procedure much easier. Biodegradable stents seem promising supplement in the treatment of pancreaticobiliary strictures with DBE-ERC. However, this is the first report of seven cases with these stents. In the future, more controlled studies with adequate number of patients are needed.

Conclusion

The new biodegradable Archimedes stent, which can be passed through working channel of a long enteroscope, seems a promising supplement in the treatment of biliary or hepaticojejunal anastomosis strictures in altered anatomy. The benefit is that no stent removal is needed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Maaser C, Lenze F, Bokemeyer M, et al. Double balloon enteroscopy: a useful tool for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in the pancreaticobiliary system. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(4):894–900.

- Siddiqui AA, Chaaya A, Shelton C, et al. Utility of the short double-balloon enteroscope to perform pancreaticobiliary interventions in patients with surgically altered anatomy in a US multicenter study. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(3):858–864.

- Machado da Ponte-Neto A, Bernardo WM, de A, Coutinho LM, et al. Comparison between enteroscopy-based and laparoscopy-assisted ERCP for accessing the biliary tree in patients with roux-en-y gastric bypass: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2018;28(12):4064–4076.

- Haapamäki C, Kylänpää L, Udd M, et al. Randomized multicenter study of multiple plastic stents vs. covered self-expandable metallic stent in the treatment of biliary stricture in chronic pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2015;47(7):605–610.

- Dumonceau JM, Tringali A, Papanikolaou IS, et al. Endoscopic biliary stenting: indications, choice of stents, and results: European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) clinical guideline - Updated October 2017. Endoscopy. 2018;50(9):910–930.

- Visconti Thiago A, de C, Bernardo WM, Moura DTH, et al. Metallic vs plastic stents to treat biliary stricture after liver transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on randomized trials. Endosc Int Open. 2018;06(08):E914–E923.

- Siiki A, Rinta-Kiikka I, Sand J, et al. Endoscopic biodegradable biliary stents in the treatment of benign biliary strictures: first report of clinical use in patients. Dig Endosc. 2017;29(1):118–121.

- Siiki A, Sand J, Laukkarinen J. A systematic review of biodegradable biliary stents: promising biocompatibility without stent removal. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30(8):813–818.

- Lakhtakia S, Yaacob NY, Jarmin R, et al. Novel Bio-degradable stent in patients with biliary or pancreatic obstruction: a pilot study to assess clinical efficacy and safety. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87(6):AB71–AB72.

- Sato T, Kogure H, Nakai Y, et al. Double-balloon endoscopy-assisted treatment of hepticojejunostomy anastomotic strictures and predictive factors for treatment success. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(4):1612–1620. [epub ahead of print]

- Haapamäki C, Udd M, Kylänpää L. Benign biliary strictures treated with fully covered metallic stents in patients with surgically altered anatomy using double balloon enteroscopy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2015;25(12):1029–1032.

- Anderloni A, Fugazza A, Maroni L, et al. New biliary and pancreatic biodegradable stent placement: a single-center, prospective, pilot study (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(2):405–411.