Abstract

Objectives

Although cirrhosisis a major cause of liver-related mortality globally, validation studies of the administrative coding for diagnoses associated with cirrhosis are scarce. We aimed to determine the validity of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) codes corresponding to cirrhosis and its complications in the Swedish National Patient Register (NPR).

Methods

We randomly selected 750 patients with ICD codes for either alcohol-related cirrhosis (K70.3), unspecified cirrhosis (K74.6) oesophageal varices (I85.0/I85.9), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, C22.0) or ascites (R18.9) registered in the NPR from 72 healthcare centres in 2000–2016. Hospitalisation events and outpatient visits in specialised care were included. Positive predictive values (PPVs) were calculated using the information in the patient charts as the gold standard.

Results

Complete data were obtained for 630 (of 750) patients (84%). For alcohol-related cirrhosis, 126/136 cases were correctly coded, corresponding to a PPV of 93% (95% confidence interval, 95%CI: 87–96). The PPV for cirrhosis with unspecified aetiology was 91% (121/133, 95%CI: 85–95) and 96% for oesophageal varices (118/123, 95%CI: 91–99). The PPV was lower for HCC, 84% (91/109, 95%CI: 75–90). The PPV for liver-related ascites was low, 43% (56/129, 95%CI: 35–52), as this category often consisted of non-hepatic ascites. When combining the ascites code with a code for chronic liver disease, the PPV for liver-related ascites increased to 93% (50/54, 95%CI: 82–98).

Conclusions

The validity of ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis, oesophageal varices and HCC is high. However, coding for ascites should be combined with a code of chronic liver disease to have an acceptable validity.

Introduction

Cirrhosis, which is increasing in incidence worldwide, is a major cause of liver-related mortality and morbidity [Citation1]. A correct estimation of the disease burden is necessary to assess the epidemiology of liver disease, study disease trends and provide an accurate inference of research findings. Administrative data from Swedish national registers is useful to identify and delineate liver-related events across different healthcare systems. Several coding systems are used, with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes being one of the most common [Citation2]. Such data play an important role in ascertaining exposures and outcomes for a large number of scientific studies, including when estimating the global burden of cancer incidence or the risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis [Citation3,Citation4]. However, the high accuracy of any coding system is vital to reduce the risk of false positives.

Most validation studies for liver-related administrative health data [Citation5–8] originate from the USA, where ICD-9 codes were used until 2015, unlike the Nordic countries where ICD-10 was introduced already in the 1990s [Citation9,Citation10]. The healthcare system and the financing of care in the USA are also different from that in most European countries where publicly funded health care is more common. Because of reimbursement issues, ICD coding might differ depending on the healthcare system [Citation11]. Establishing the validity of ICD codes is therefore needed. Another issue is that previous research has mainly validated ICD codes in small cohorts or cohorts derived from tertiary liver units [Citation12,Citation13], which is likely to suffer from selection bias and has implications on generalisability. Based on these issues, our study aimed to validate and calculate positive predictive values (PPVs) of ICD-10 codes for liver-related events in a nationwide setting.

Material and methods

Swedish registers and the personal identity number

In Sweden, all patient visits for specialised care are registered in the Swedish National Patient Register (NPR). The NPR was established in 1964 with data from inpatient visits, with nationwide coverage not occurring until 1987. In 2001, registration of specialised outpatient care was introduced [Citation14]. The responsible physician determines the ICD codes for the main and contributing diagnoses at the time of the health care contact. These codes are preserved locally and regularly transferred to the national registers. The registers are continuously updated. Since 1997, ICD-10 codes have been used in Sweden [Citation14]. The Swedish personal identity number (PIN) is a unique12-digit code given to all Swedish residents. The PIN can be used in research for linkages between registers, and data collected by the researcher [Citation15].

Data collection

We sought to validate a random selection of the following diagnoses registered in the NPR from 2000–2016: cirrhosis without aetiology (K74.6), alcohol-related cirrhosis (K70.3), oesophageal varices with or without bleeding (I85.0 and I85.9), ascites (R18.9) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, C22.0). These codes were selected given that they are clinically significant liver-related outcomes in hepatology research and unlikely to be missed, that is, occurrence of the medical condition is likely to be captured by the reporting physician. Patients with ICD codes registered at hospitalisation events and outpatient visits in specialised care were randomly selected from healthcare institutions throughout Sweden by the National Board of Health and Welfare. The date of the coding event was also random concerning the patient’s journey through the healthcare system, that is, we did not select, for example, the first or most recently recorded event. For each case, we received from the NPR (1) the patients’ PIN, (2) the date of the healthcare contact when the code was registered and (3) the name of the healthcare provider where the registration of the code took place. To achieve a positive predictive value of at least 80%, a power calculation estimated that 120 patients with each diagnosis would be needed. As obtaining charts in all patients was not expected, 150 patient charts for each diagnosis to be validated were requested.

In total, 72 health care providers (listed in Supplementary Table 1), including all university hospitals and representing every health care region in Sweden, were contacted by the principal author (BB). For every case, we requested patient charts 2 years before and 2 years after the registration date of the target ICD code. Charts included physician notes, radiology and pathology reports and endoscopy notation. We excluded cases in which there were insufficient data in the medical charts to ascertain the investigated diagnosis. The ICD code from the NPR was then compared with medical records from 2 years before the date of the diagnosis up to 2 years after the diagnosis. This comparison was used as the gold standard.

Variables

A strict list of criteria was applied to define the presence or absence of the investigated diagnoses. Cirrhosis (K70.3 and K74.6) was defined as present if one or more of the following criteria were present: (1) liver biopsy with features of cirrhosis reported as fibrosis stage 4; (2) radiological evidence of cirrhosis (nodular and shrunken liver or signs of portal hypertension without a competing cause); (3) ascites or oesophageal varices together with a physician’s annotation documenting cirrhosis.

We did not confirm whether alcohol was indeed the aetiology of cirrhosis in alcohol-related cirrhosis (K70.3), but only if cirrhosis were present or not. Oesophageal varices were defined as present if there were an upper endoscopy showing oesophageal varices (bleeding or not bleeding, I85.0/I85.9). When records from endoscopy were missing, varices were considered present if a physician’s entry stated oesophageal varices treated with band ligation.

In ICD-10 the code for ascites (R18.9) is used for ascites from all causes. In this study, we validated to what extent the ICD code was used for ascites caused by chronic liver disease and thus here PPVs represent cirrhotic ascites. The definition of ascites was based on clinical examination by a physician or by radiology, and the cause of ascites was defined as liver-related or not. For instance, a patient with gynaecological cancer upon chart review and no indication of cirrhosis was defined as not having cirrhosis-related ascites.

The diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma was either biopsy-proven or based on radiological reports of typical findings for HCC as described in the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines [Citation16].

If the patient had any other ICD codes corresponding to chronic liver disease (not necessarily cirrhosis and defined in ) within 2 years from the date of the validated ICD-10 code, these codes were recorded. For instance, an ascites event was recorded if a patient had a code for ascites with no additional coding for cirrhosis at the time of the event, but a code for hepatitis C 1 year before the ascites event.

Table 1. ICD codes defining chronic liver disease.

For the validated ICD-10 codes with a PPV of <90% when used in isolation, we calculated whether the requirement of an additional code for chronic liver disease increased the PPV (e.g., a patient with ascites was considered to have chronic liver disease if a code of hepatitis C was found in the patient chart a year before the date of the ascites event). We also investigated whether the PPVs were higher across pre-specified subgroups that included codes registered at university hospitals in contrary to other hospitals; ICD codes registered from hospitalisation events in opposite to ICD codes from outpatient visits; and ICD codes registered at a gastroenterology, internal medicine or transplant clinic vs. all other clinics.

Statistical analysis

Data management was performed using Microsoft Excel and StataSE software v15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). PPVs were calculated and presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI) using the diagtpackage in StataSE.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the regional ethical committee in Stockholm (reg no 2017/1019‐31/1). Because of the retrospective nature of the data collection process and because there was no direct contact with any of the patients, informed consent was waived by the ethical committee [Citation17].

Results

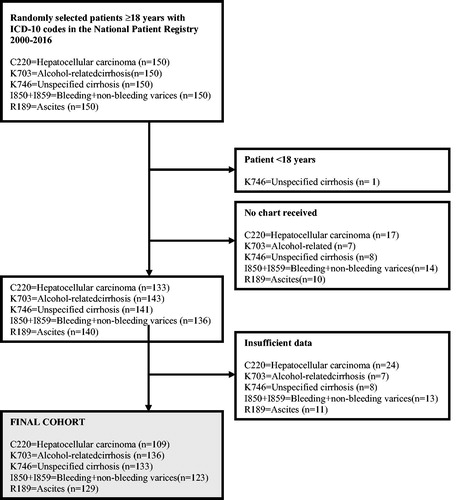

We received 694 of the requested 750 medical charts (92%) from healthcare providers. We excluded one patient that was <18 years of age at the time of diagnosis. Of the 693 remaining charts, 63 (9%) had insufficient information to allow any validation. The final validation cohort therefore comprised 630 patients (84% of the full cohort) with an ICD-10 code for either alcohol-related or unspecified cirrhosis (available data in n = 269/300, 90%), oesophageal varices (n = 123/150, 82%), HCC (n = 109/150, 73%) or ascites (n = 129/150, 86%). A flowchart for patient inclusion is presented in . We compared excluded (n = 120) and included (n = 630) patients and found that excluded patients were older (median age 68 years vs. 64 years, p < .001) and less likely to have the ICD-10 code registered at a university hospital (25/120, 21% vs. 247/630, 39%, p <.001). No difference in sex was found between included and excluded patients.

The median age of the final cohort was 64 years (range 22–97) and 61% (n = 382/630) were men. A majority (62%) had been diagnosed as inpatients and most (71%) had the defining ICD-10 code registered at a non-university hospital. For alcohol-related cirrhosis 11/136 cases (8%) were biopsy-proven and for unspecified cirrhosis, 25/133 cases (19%) were biopsy-proven.

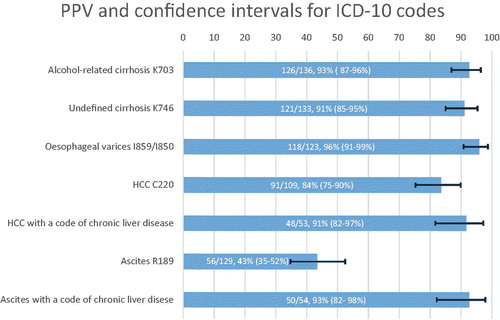

We found PPVs above 90% for codes corresponding to alcohol-related cirrhosis 126/136 (PPV = 93%, 95%CI: 87–96), cirrhosis with unspecified aetiology 121/133 (PPV = 91%, 95%CI: 85–95) and oesophageal varices 118/123 (PPV = 96%, 95%CI: 91–99). In cases where our criteria for cirrhosis were not fulfilled, the diagnosis in the patient chart was typically based on minor radiological findings or abnormalities in liver blood tests, implicating that the case did not fulfil our criteria for cirrhosis. Portal vein thrombosis was present but no cirrhosis in two cases. For oesophageal varices, wrongly coded patient charts (n = 5) included two cases of gastric ulcers with bleeding, one Mallory Weiss bleeding and one case of varices in the lower limb.

The PPV was somewhat lower for HCC, where 91/109 patient charts fulfilled criteria for HCC (PPV = 84%, 95%CI:75–90). In 53/109 (49%) patients with an ICD code for HCC, an added code for chronic liver disease within 2 years was found. In 48 of these 53 patients, the HCC diagnosis was true, corresponding to a PPV of 91% (95%CI:79–97). However, using this strategy resulted in not capturing 43 patients with a true HCC but without a code for chronic liver disease within 2 years, leading to missed cases. Some HCC cases (n = 24) were diagnosed late in a palliative stage when ascertaining the diagnosis was not prioritised. These cases had insufficient data to meet the international recommendation for a diagnosis of HCC. These cases were therefore excluded from the main analysis, although they were highly suspected of having HCC. When these cases were included in a sensitivity analysis, the PPV for HCC was slightly higher: 87% (115/133, 95%CI: 80–92).

The ICD code for ascites was, as defined above, validated for ascites due to liver disease and not the presence of ascites in general. Of the 129 cases, ascites was present in 128 (99%). Of noteworthy is that only 56/129 (PPV = 43%, 95%CI: 35–52) of the cases had ascites related to liver disease. Typically, in cases not considered caused by liver disease, gynaecologic cancers (27/129) and GI tumours (20/129) were the causes of ascites. Other non-liver causes included heart failure, nephrotic syndrome and other cancers. Some 54/129 patients had coding for a chronic liver disease within 2 years of the date of ascites (defined in ). When the ICD-10 code for ascites was combined with a code for chronic liver disease, the diagnosis was correct in 50/54 cases (PPV = 93%, 95%CI: 82–98). PPVs for validated ICD-codes are also presented in .

Figure 2. PPV (%) with 95% confidence intervals for validated ICD-10 codes. ICD-10 codes to define chronic liver disease are presented in . These codes were registered if found in the patient chart within 2 years from the date of the validated ICD code.The PPV for K70.3 refers to the presence of cirrhosis in these patients. We did not evaluate the aetiology (alcohol or not) of these patients. PPV: positive predictive value; ICD: International Classification of Diseases; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma.

In a subgroup analysis in which only ICD codes registered from hospitalisations were included, PPVs were similar to the primary analysis. An exception was HCC in which the PPV increased from 84% (91/109) to 93% (75/81). When including ICD-10 codes registered at gastroenterology, internal medicine or transplant clinics only, PPV for oesophageal varices increased to 100% (69/69) and ascites to 70% (40/57), whereas no major changes were seen in ICD-10 codes corresponding to cirrhosis and HCC. However, this strategy resulted in the algorithm of not capturing49 cases of varices (42%) and 16 ascites cases (29%). ICD codes registered at a university hospital yielded a higher PPV for all ICD codes, except for HCC. PPVs, together with 95% CIs for all diagnoses and sub-analyses, are presented in and .

Table 2. Positive predictive values with 95% confidence intervals for ICD-10 codes in the Swedish National Patient Register for liver-related events when compared to patient charts.

Table 3. Positive predictive values with 95% confidence intervals for subgroup analysis of ICD-10 codes in the Swedish National Patient Register for liver-related events when compared to patient charts.

Discussion

Our main finding was the high validity of ICD-10 codes for cirrhosis and oesophageal varices in the Swedish NPR. However, the ICD-10 code for ascites alone had an unsatisfactory low PPV because many patients had ascites caused by other pathologies than liver diseases. When combined with a code for chronic liver disease within 2 years of the ascites event, there was a significant increase in the PPV. This finding suggests that when ascertaining ascites as an outcome for patients with known chronic liver diseases using the ICD code for ascites seems satisfactory. However, when examining the incidence of ascites due to cirrhosis in patients without known chronic liver disease, coding representative of chronic liver disease must also be added; otherwise, false-positive events are likely to be included to an unacceptable extent.

The PPV for HCC was slightly lower (84%) than that of cirrhosis, which could be an effect of the strict HCC definition used in our study. When an additional ICD code for chronic liver disease was required, PPV increased to 91% but with the serious ramification that nearly half (47%) of the accurately coded HCC cases were excluded. One part of the explanation could be that 10–20% of HCC cases occur in patients with no chronic liver disease [Citation16]. These results are relevant when performing register-based research on chronic liver disease and, in particular, in Sweden. However, we suspect that similar results would also be found in health care registers of other countries.

Our results should be compared to previous studies. A Danish study from 1997 validated ICD-8 codes for cirrhosis in 198 patients and estimated the PPV to 85% [Citation18]. In a validation study of liver-related diagnoses in the Veteran Affairs system in the USA, the PPV for cirrhosis using ICD-9 codes was 90% [Citation8], which is consistent with our results. In another study from the USA, ICD-9 codes from both inpatient and outpatient visits were validated for the presence of cirrhosis. The authors found that most individual ICD-9 codes, except that of ascites, had high PPVs for identifying cirrhosis (range 78–94%). Only 63% of patients with an ICD code for ascites had cirrhosis in that study [Citation5].

The main strength of this study is the nationwide and random identification of patients from different medical facilities throughout Sweden, increasing external validity. We received a high degree of the requested medical charts (94%) from health care providers. When excluding charts with insufficient information, we were still able to review 84% of our original sample. Gender distribution and median age in our cohort are consistent with previous publications from our geographical area [Citation19,Citation20].

The study has several limitations. One concerns the difference in the quality and amount of data sent from different health care providers, which might have had an impact on how often a diagnosis of chronic liver disease could be found or not. Another drawback is that we could not estimate other test characteristics than the PPV. Finally, we did not consistently validate the first registered cirrhosis diagnosis (or related diagnoses) in each patient. Hence, we were unable to decide the diagnostic correctness of codes assigned by the time of the first diagnosis. Of note, we also evaluated the PPV for the presence of cirrhosis when examining patient charts of individuals with alcohol-related cirrhosis and not the exact aetiology (alcohol or not) of the cirrhosis.

Algorithms of several ICD codes to identify cirrhosis and decompensation events have been used in many studies [Citation7,Citation13,Citation21,Citation22]. One disadvantage of an algorithm is that patients are only seen once in hospital or who die after receiving only one ICD code might not be identified. Therefore, an important finding in our study is that when using the NPR, it is sufficient to use a single ICD code for cirrhosis, varices and HCC. However, our results suggest that it is not advisable to use an ICD-10 code for ascites alone in some studies (e.g., general population studies) when examining liver-related outcomes in cohorts without known liver disease. However, adding anICD-10 code for chronic liver disease can solve this issue.

Conclusions

The validity of administrative ICD-10 coding associated with cirrhosis was high in the Swedish NPR, suggesting that for most diagnoses there is no need to construct algorithms when defining outcomes. The PPV for ascites due to liver disease was lower and adding a code for chronic liver disease to this condition is recommended.

Author contributions

Study conception and design: HH, JFL; Acquisition of the data: BB; Statistical analysis: HH; Analysis and interpretation of the data: HH, BB; Drafting of the manuscript: BB, HH; Critical revision: All; Guarantor of article: HH; All authors approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list.

| Abbreviations | ||

| CI | = | confidence interval |

| EASL | = | European Association for the Study of the Liver |

| HCC | = | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| ICD | = | International Classification of Diseases |

| NPR | = | National Patient Register |

| PPV | = | positive predictive value |

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Asrani SK, Devarbhavi H, Eaton J, et al. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019;70(1):151–171.

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Information Sheet [internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2020 May 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/factsheet/en/

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424.

- Olen O, Erichsen R, Sachs MC, et al. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10218):123–131.

- Nehra MS, Ma Y, Clark C, et al. Use of administrative claims data for identifying patients with cirrhosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47(5):e50–e54.

- Goldberg D, Lewis J, Halpern S, et al. Validation of three coding algorithms to identify patients with end-stage liver disease in an administrative database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(7):765–769.

- Niu B, Forde KA, Goldberg DS. Coding algorithms for identifying patients with cirrhosis and hepatitis B or C virus using administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(1):107–111.

- Kramer JR, Davila JA, Miller ED, et al. The validity of viral hepatitis and chronic liver disease diagnoses in Veterans Affairs Administrative Databases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(3):274–282.

- Schiøler G, Smedby B. Health Classifications in the Nordic Countries-Historic development in a National and International perspective. In: Nordisk medicinalstatistisk kommitté. 1st ed. Copenhagen: Schultz Information; 2006.

- Hirsch JA, Nicola G, McGinty G, et al. ICD-10: history and context. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37(4):596–599.

- McNeely CA, Brown DL. Gaming, upcoding, fraud, and the stubborn persistence of unstable angina. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(2):261–263.

- Lo Re V, Lim JK, Goetz MB, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes and liver-related laboratory abnormalities to identify hepatic decompensation events in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(7):689–699.

- Lapointe-Shaw L, Georgie F, Carlone D, et al. Identifying cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in health administrative data: a validation study. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201120.

- Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450.

- Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, et al. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol. 2009;24(11):659–667.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address eee, European Association for the Study of the L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236.

- Ludvigsson JF, Haberg SE, Knudsen GP, et al. Ethical aspects of registry-based research in the Nordic countries. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:491–508.

- Vestberg K, Thulstrup AM, Sorensen HT, et al. Data quality of administratively collected hospital discharge data for liver cirrhosis epidemiology. J Med Syst. 1997;21(1):11–20.

- Nilsson E, Anderson H, Sargenti K, et al. Incidence, clinical presentation and mortality of liver cirrhosis in Southern Sweden: a 10-year population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(12):1330–1339.

- Gunnarsdottir SA, Olsson R, Olafsson S, et al. Liver cirrhosis in Iceland and Sweden: incidence, aetiology and outcomes. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(8):984–993.

- Sada Y, Hou J, Richardson P, et al. Validation of case finding algorithms for hepatocellular cancer from administrative data and electronic health records using natural language processing. Med Care. 2016;54(2):e9.

- Philip G, Djerboua M, Carlone D, et al. Validation of a hierarchical algorithm to define chronic liver disease and cirrhosis etiology in administrative healthcare data. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0229218.