Abstract

Background

Infliximab (IFX) is used in active Crohn’s disease for induction and maintenance of remission. There are scanty data on weight gain in IBD-patients under anti-TNF treatment. We investigated changes in weight and blood chemistry in anti-TNF-naïve Crohn’s disease patients during their first course of IFX.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of 110 patients (77 men, 33 women) aged 34 years (range 14–73), 54 with luminal and 56 with fistulising disease, given at least 3 infusions of IFX (range 3–11). Data regarding body weight, height, C-reactive protein (CRP), haemoglobin and S-albumin at baseline, before the third infusion, at three months and at 12 months were collected.

Results

At 6 weeks, 65 (59%) increased in weight, 73% and 76% at three and 12 months, respectively. There was an increase in median weight (1.7 kg, IQR = 3.1 kg) and BMI (0.5 kg/m2, IQR = 1.2 kg/m2) at 6 weeks, which persisted at three and 12 months (all p < .001). There was no difference between men and women. Young patients, patients with underweight or fistulising disease increased most in weight. Disease activity assessed by PGA and SES-CD decreased at all time points (p < .05). Increases in weight and BMI correlated with an increase in serum albumin and a decrease in CRP.

Conclusion

Approximately 60% of Crohn’s disease patients experience weight gain within the first six weeks of infliximab treatment. The weight increment correlates with improvements in inflammatory markers and disease activity. The causes of weight gain may be related to treatment induced metabolic changes and reduced inflammatory burden.

Introduction

With the introduction in 1999 of anti-TNFα-antibodies for the treatment of various immunological and inflammatory disorders, this drug class has renewed treatment approaches to patients with gastrointestinal, rheumatological and skin disorders [Citation1–6]. It is widely accepted that TNFα plays a strategic role in several inflammatory pathways involved in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [Citation7] and Infliximab (IFX) has become widely used for induction and maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis [Citation8–13]. Approximately one third of patients with IBD will not respond to initial treatment (primary non-responders) with IFX, and in patients on maintenance therapy the annual risk for loss of response is 10–13% per patient-year [Citation9,Citation11,Citation12]. Adequate serum IFX levels are associated with improved clinical outcome in IBD; however, the formation of antidrug antibodies increase clearance and decrease anti-TNF levels [Citation14,Citation15].

Significant weight loss is often observed in patients with active IBD [Citation16]. General malaise and nausea, e.g., caused by thiopurines, may play a role. Weight gain induced by appetite stimulation by corticosteroids is often present and has further been associated with anti-TNF treatment, as seen in rheumatological disorders such as psoriatic arthritis, spondylarthropathy and rheumatoid arthritis [Citation17–19]. Little is known about the cause of the observed weight gain. Some studies have identified correlation with the inflammatory syndrome [Citation20], or between baseline body weight and weight gain [Citation21–24]. Overall, there are scanty systematic data on weight gain and metabolic changes in IBD-patients under anti-TNF treatment.

We noticed early, when introducing infliximab into the clinic, that some, but not all, patients increased their body weight during treatment. Therefore, the aim of this study was to, (i) investigate changes in weight and blood chemistry in anti-TNF-naïve patients during their first course of IFX, and, (ii) to investigate a possible correlation between weight gain and change in disease activity.

Patients and methods

Study population

A retrospective review of medical records was conducted. Patients were treated with infliximab between the years 2000 and 2014 at the Karolinska University Hospital or at Linköping University Hospital in Sweden. Disease location and behavior characteristics were classified according to the Montreal classification [Citation25].

All CD-patients treated at the two centers were considered for inclusion in the study. The eligibility criteria were; (i) being naïve for anti-TNF treatment, (ii) been given at least three doses (range 3–11) of infliximab, and, (iii) having complete baseline data on height and weight. Patients could previously have received other treatments for IBD, such as thiopurines and glucocorticosteroids but neither anti-TNF nor other biological drugs.

Anti TNF administration

Infliximab was administered as three intravenous infusions (5 mg/kg BW) at week 0, 2 and 6. Patients who responded or obtained remission were then given maintenance treatment every 8 weeks; these patients were evaluated at 12 months.

Follow-up

Data regarding weight, height, CRP, serum albumin and haemoglobin at baseline, 6 weeks, 3 months and 12 months were extracted from medical records. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m) × height (m) and was classified according to the standard definition of BMI; Underweight was defined as BMI ≤18.49 kg/m2, normal weight as BMI 18.5–24.99 kg/m2, overweight as BMI 25–29.99 kg/m2 and obesity as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 [Citation26].

Overall disease activity was graded on a 4-grade scale as a ‘physician global assessment’, PGA, by one experienced gastroenterologist without access to endoscopy or laboratory results. Presence of diarrhoea, stool frequency, abdominal pain, fatigue, presence of fever and weight loss were taken into account and a composite score reached. Grade 0, was clinical remission, grade 1, mild disease activity, grade 2, moderate disease activity, and, grade 3, severe disease activity. Patients were during follow-up classified as Responders, i.e., a decrease in PGA, or as Non-responders, i.e., no change or an increase in PGA.

The endoscopic severity was assessed by the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease (SES-CD) [Citation27].

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, descriptive statistics, independent samples T-test and non-parametrical two-group comparisons were used. Correlation models (Pearson’s) were used to analyze association between weight or BMI and inflammatory markers or response at 6 weeks, 3 and 12 months of treatment. Continuous variables are presented as mean and SD or as median and interquartile range (IQR) with a 95% confidence interval and categorical variables as frequencies. A probability of less than 5% (p < .05) was accepted as statistically significant. All statistical evaluations were performed with IBM SPSS statistics software 22.0 and 25.0.

Ethics

The study was approved by the committee of research ethics at Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden (Dnr 2007/4:10).

Results

Demographics

One hundred and ten CD-patients met the eligibility criteria. Their baseline characteristics are listed in . There were 77 (70%) males and 33 females. At inclusion, smoking status was available in 97 patients; there were 92 non-smokers (95%), three x-smokers and two smokers. The mean age at start of IFX-treatment was 34 years (range 14–73 years); 74% of all patients were below the age of 40. 84 patients (76%) had concomitant treatment with azathioprine and/or glucocorticosteroids.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 110 Crohn’s disease patients starting infliximab treatment.

106 patients (96%) continued treatment for 3 months and 85 patients (77%) for at least 12 months. The remaining 25 patients (23%) did not continue treatment beyond six weeks for various reasons; primary non-response (20), being in remission (4), or change to other medication (1). There were no baseline differences between these 25 patients compared to the 85 patients treated for at least 12 months when it comes to gender, weight, BMI, disease location, co-medication, previous surgeries, disease type and laboratory findings (data not shown).

Of 34 patients (31%) having endoscopy performed within 3 months before start of infliximab, 26 (76%) had a follow-up endoscopy during maintenance treatment.

Weight changes over 12 months

Complete data on height and weight at 6 weeks was available for all patients, for 96% at 3 months and for 77% at 12 months. At 6 weeks, 65 (59%) patients increased in weight, 21 decreased and 24 had no change. Of the 106 patients continuing treatment after the induction phase, at 3 months 77 (73%) had increased in weight, 16 decreased and 13 had no change. At 12 months, 65 of 85 patients (76%) under maintenance treatment increased in weight, 18 patients decreased in weight and 2 had no change compared to baseline. None of the underweight patients lost weight. Even if a small number of normal weight patients lost weight, the proportion of overweight plus obese patients that lost weight was at all time points higher (at 6 weeks, 50%; 3 months 32%; 12 months 52%) compared to normal weight patients (at 6 weeks, 15%; 3 months 10%; 12 months 11%; all p < .02).

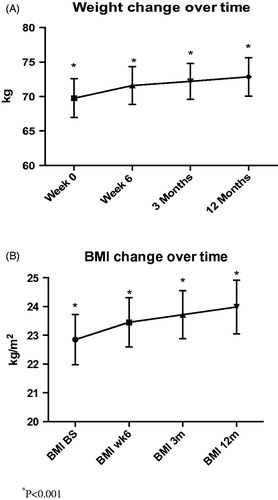

Overall, there was a significant increase in weight (median 1.7 kg, IQR = 3.1 kg) and BMI (median 0.5, IQR = 1.2 kg/m2), at 6 weeks of treatment (both p < .001), which persisted at 3 and 12 months, (3 months; 2.4 kg, IQR = 4.7 kg and BMI; 0.7 kg/m2, IQR = 1.5 kg/m2, both p < .001; 12 months; 3.0 kg, IQR = 6.4 kg and BMI; 1.0 kg/m2, IQR = 2.2 kg/m2, both p < .001) (). There was no difference in weight change between men and women at any time point.

Figure 1. (A) Weight increment in Crohn’s disease patients during induction and maintenance treatment with infliximab. There was a significant increase in weight at all time points compared to baseline (p < .001). The median increase in weight was 1.7 kg (IQR = 3.1 kg) at 6 weeks of treatment, which persisted at 3 and 12 months, 2.4 kg (IQR = 4.7 kg) and 3.0 kg (IQR = 6.4 kg), respectively. (B) BMI increment in Crohn’s disease patients during induction and maintenance treatment with infliximab. There was a significant increase in BMI at all time points (p < .001). The median increase in BMI was 0.5 kg/m2 (IQR = 1.2 kg/m2) at 6 weeks of treatment, which persisted at 3 and 12 months, BMI; 0.7 kg/m2 (IQR = 1.5 kg/m2) and 1.0 kg/m2, (IQR = 2.2 kg/m2), respectively.

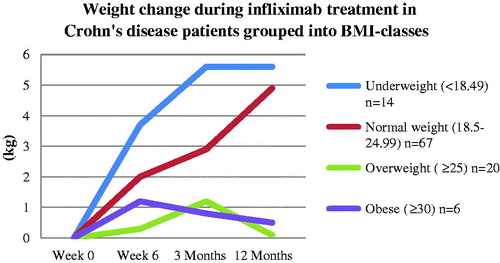

Underweight patients increased significantly more in weight and BMI than overweight patients at 6 weeks and 3 months (both p < .01) (). Normal weight patients increased significantly more in weight and BMI compared with overweight patients at 12 months of treatment (p < .05). Patients with a normal BMI at baseline tended to increase more in weight and BMI compared with overweight and obese patients at all time points (P = NS, data not shown).

Figure 2. Underweight Crohn’s disease patients at baseline increased more in weight than normal, overweight and obese patients at 6 weeks of treatment (p < .05). Patients with a normal BMI at baseline increased more in weight at 12 months compared to overweight patients (p < .01).

In respect of disease location, L1, L2, or L3, uniform changes in weight and BMI was seen (data not shown). Patients with fistulising disease increased more in weight and BMI at 12 months of treatment than patients with luminal disease (both p < .05); the same tendency was already seen at 6 weeks and 3 months (P = NS) (). There was no significant difference in weight and BMI changes between patients that had undergone bowel resection or not (data not shown). Patients with infliximab monotherapy increased at 12 months more in weight (5.5 vs. 0.5 kg, p < .01) and BMI (1.9 vs. 0.2 kg/m2, p < .01) compared with patients receiving glucocorticosteroids without azathioprine at baseline. Disease activity did not differ between these two groups at baseline.

Table 2. Weight and BMI increases during infliximab-treatment stratified for disease type in 110 Crohn’s disease patients.

Patients below the median age of 32 years had a larger increase in weight at 6 weeks (2.8 kg vs. 0.8 kg) and BMI (0.9 kg/m2 vs. 0.3 kg/m2,both p < .001), compared to older patients; increases which persisted at 3 and 12 months (p < .001 and p < .01, respectively).

Patients with a baseline CRP >3 increased more in weight at 6 weeks and 3 months compared with patients with CRP <3 (2.2 vs. 1.1 kg, and, 3.2 vs. 1.7 kg, both p < .05). Patients with CRP >10 increased significantly more in weight at 3 months compared with patients with CRP <10 (3.7 vs. 2.0 kg, p < .05).

Changes in disease activity

Disease activity as reflected in PGA decreased at 6 weeks of treatment (PGA −1,1, 95% CI: −1.2 to (–1.0) p < .001), and persisted at 3 and 12 months (3 months; −1.3, 95% CI: −1.5 to (–1.1), p < .001, 12 months; −1.5, 95% CI: −1.7 to (–1.3) p < .001). There was no difference in change of disease activity over time between men and women.

There were no significant differences in changes in weight and BMI between responders and non-responders to IFX at any time point (data not shown). At 6 weeks, responders (n = 82) decreased significantly more in CRP (–15.7 vs. −0.9, p < .01) and had a larger increase in serum albumin (3.7 vs. 0.85, p < .05) compared with non-responders (n = 23). At 12 months, responders (n = 68) had a larger increase in serum albumin compared with non-responders (n = 9) (4.5 vs. −0.9 p < .01).

Changes in inflammatory markers

CRP decreased at 6 weeks of treatment, which persisted at 3 and 12 months (both p < .001). Serum albumin increased at 6 weeks of treatment, and persisted at 3 and 12 months (all p < .001) (). Haemoglobin levels increased at 3 and 12 months of treatment (both p < .001) and was significant in both men and women (p < .01) (). When comparing men and women, there was no difference between men and women at any time point regarding changes in CRP, albumin and haemoglobin levels.

Table 3 Changes in inflammatory markers in 110 Crohn’s disease patients under infliximab treatment (77 men, 33 women).

Patients with ileocolonic disease location (L3) increased more in serum albumin at 3 months compared to patients with colonic disease (L2) (5.5 vs. 3.1, p < .05). CRP decreased more in patients with colonic or ileocolonic disease compared to patients with ileal disease at 3 months (–12.2 vs. −1.3, p < .05, and, −21.0 vs. −1.3, p < .01), which persisted at 12 months of treatment (–12.7 vs. 2.7 and −20.1 vs. 2.7, both p < .01).

Endoscopy

The endoscopic grading according to SES-CD was reduced in patients at 6 months (n = 19; SES −10.1, 95% CI: −16.1 to (–4.1), p < .01) and at 9 months (n = 26; SES −9.1, 95% CI: −14.2 to (–4.0), p < .01) compared to findings at baseline. Patients with baseline CRP > 3 improved significantly more in endoscopic grading at 6 months compared with patients with CRP < 3 (–15.0 vs. −4.0, p < .01).

Correlations

Weight

The weight gain was at all time points negatively correlated with the decrease in CRP (6 weeks; r = –0.35, p < .001, 3 months; r = –0.39, p < .001, 12 months; r = –0.26, p < .05) and correlated positively with the increase in serum albumin (6 weeks; r = 0.47, p < .001, 3 months; r = 0.36, p < .001, 12 months; r = 0.34, p < .01). The increase in weight was positively correlated with increase in haemoglobin at 6 weeks and at 12 months of treatment (6 weeks; r = 0.28 p < .01; 12 months; r = 0.29, p < .01). Also, weight changes at all time points correlated with baseline CRP (6 weeks; r = 0.3, p < .01, 3 months; r = 0.3, p < .001, 12 months; r = 0.2, p < .05).

Disease activity

The weight gain parallelled the decrease in PGA at all time points (6 weeks; r = –0.26, p < .01, 3 months; r = –0.26, p < .001, 12 months; r = –0.22, p < .05) as did a decrease in PGA with a rise in serum albumin (6 weeks; r = –0.45, p < .001, 3 months; r = –0.29, p < .01, 12 months; r = –0.51, p = .001) and with a decrease in CRP (6 weeks; r = 0.29, p < .01, 3 months; r = 0.31, p < .01, 12 months; r = –0.38, p = .001). There was no obvious relation between weight gain and haemoglobin levels (data not shown).

Discussion

This study shows that treatment with infliximab in anti-TNF naïve Crohn’s disease patients is associated with an early weight gain and increased BMI, both which are sustained over time. The increase in weight occurred as early as after the second infusion with a two-week interval in-between, and continued during the 12 months of treatment. Overall, weight gain was most apparent through week 6; thereafter the patients weight continued to rise at a lower rate. The increase in weight correlated with increases in serum albumin and haemoglobin and with decreased clinical disease activity, as reflected by CRP, PGA and endoscopy findings.

Our results confirm reports in other usually smaller patient cohorts, that anti-TNF use in IBD-patients often leads to weight gain. [Citation24,Citation28–33]. Weight gain was more pronounced in patients with fistulising disease and in younger patients. The weight increment occurred early and was more pronounced in underweight and normal weight patients than in overweigh/obese patients, which is in agreement with previous observations in patients with plaque psoriasis or CD [Citation23,Citation29,Citation31]. Still, overweight and obese patients increased in weight at all time points. We did not observe any difference in weight gain between men and women, contrary to the study by Christian et al. [Citation34], where women gained less weight than men.

We stratified for concomitant therapy and observed less weight increment in groups using concomitant glucocorticosteroids at baseline. Children, using IFX and azathioprine in a top-down strategy had larger increase at two months in Z-scores for weight compared with an azathioprine-group and with a step-up group (glucocorticosteroids as induction treatment) [Citation28]. Children using glucocorticosteroids as their main treatment had a larger increase in Z-score than those using azathioprine and step-up therapy [Citation28]. When compiling data from several clinical trials of IFX, no weight gain was observed in the ‘placebo’ group in the SONIC study treated with azathioprine as mono therapy compared to the groups that received IFX [Citation34]. Similarly, we have not seen any obvious weight change in CD patients treated with 6-thioguanine or mycophenolate mofetil (unpublished observations). Taken together these observations underline that it is infliximab per se which is the most important driver for the weight gain in IBD.

Franchimont and colleagues [Citation24] observed a significant increase in weight as early as after 4 weeks of treatment. Kim with colleagues [Citation28] evaluated different TNF treatment strategies; they observed that top-down strategy (rapid start with infliximab) was associated with a significant increase in weight compared to azathioprine and step-up group. In another study, the weight gain was significantly more elevated in patients with low-BMI than patients with normal BMI [Citation29]. The mean increase in BMI was higher in patients who responded to IFX as compared with non-responders [Citation31], which was not seen in our study. Weise and coworkers [Citation32] observed a significant increase in BMI of 2.2 kg/m2 at 6 months but could not see any improvement in disease activity. In contrast to our study, Nakahigashi et al. [Citation31] found that CD-patients with small bowel involvement achieved a higher increase in weight as compared with patients without such disease location, and that responders had a higher increase than non-responders to IFX. Since neither we nor others observed any difference in weight gain when patients were stratified for disease location and previous bowel resections, most probably a systemic metabolic effect is in play [Citation35].

Nevertheless, anti-TNFα agent use in patients with other inflammatory diseases, such as psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis is associated with weight gain and reduced disease activity [Citation36–40]. The baseline weight of our patients and the weight gained at one year were comparable with previous studies in rheumatological patients [Citation23,Citation41,Citation42]. Engvall and colleagues [Citation40], however, did not see any significant difference in patients with rheumatoid arthritis between IFX and methotrexate in regard to increased BMI. Three retrospective studies assessing IFX in psoriasis patients found a significant increase in weight between 2.2 and 3.2 kg at 24 weeks of treatment [Citation18,Citation19,Citation37]. Tan and colleagues [Citation37] examined the effect of IFX on body weight compared with agents that do not target TNF. The most marked increase in body weight was observed at week 24 (IFX: 3.2 kg; adalimumab: 2.2 kg), while the authors did not observed any significant increment with other treatments. Saraceno and co-workers [Citation19] observed a significant increase in body weight and BMI for adalimumab and IFX compared with other treatments such as methotrexate at week 12, 24 and 48. Again in that study the most marked increase was seen at week 24 (IFX: 1.1 kg, adalimumab: 2.2 kg.) No difference was seen between men and women, which are in agreement with our study. The relatively risk of gaining more or equal to 5 kg body weight among patients exposed to anti-TNFα treatment was 4.3 times higher than patients exposed to methotrexate [Citation18].

Little attention has been paid to the metabolic and/or anabolic effects of TNFα-antibodies in humans. Patients report increased appetite and improved tolerance to foods, which lead to better quality of food ingested. However, resting energy expenditure was not affected in children and adolescents treated with IFX [Citation29,Citation30]. Weight gain after initiating anti-TNF is likely due to restoring the TNF-α–associated anorexia establishing a positive energy balance, potentially mediated by leptin [Citation24]. Some authors have noted an increase in fat mass without any change in lean body mass or muscle mass whereas others have noted an increase in muscle mass or lean body mass without changes in fat mass [Citation17,Citation21,Citation22,Citation32].

Although being retrospective in nature, one advantage of our study is the long study duration; we were able to observe weight changes during 12 months of maintenance treatment in a ‘real-life situation’, which to our knowledge has not previously been studied in IBD patients. Patients were treated at two university hospitals with common guidelines applied, and, only patients with the same dosing regime, i.e., IFX 5 mg/kg BW induction at 0−2−6 weeks followed by the same dose every eight weeks, were included. Thus minimizing the risk of divergent treatment strategies together with a rather large cohort of CD patients, support that our overall results are reliable and generalizable.

Some weaknesses are obvious. Being retrospective in nature, full data sets were not available for all patients. Disease activity was possible to assess in approximately half of the patients, and it would have been preferable to have applied an established activity index, such as Harvey-Bradshaw index, together with the PGA-grading used. At the time of study, measurement of faecal calprotectin, as an ‘objective’ marker of disease activity, and serum-IFX levels had not been incorporated in routine care. We did not investigate body composition, diet, physical activity or made comparison with a control group using other treatments (e.g., azathioprine and glucocorticosteroids). Hence, change in the patients lifestyle during treatment, could have accounted for some of the observed weight change.

Even if previous reports in patients with various chronic inflammatory conditions, have provided conflicting results on the influence of anti-TNF therapy on metabolic parameters, probably due to small sample sizes and short duration of follow-up (4–30 weeks) [Citation24,Citation29–31], it is conceivable to consider that patients increase in weight due to a combination of diminished inflammatory burden and increased well-being at the same time as they can engage in more physical activities and therefore eat more.

Leptin levels are significantly increased in CD patients at 4 weeks of treatment and occurred as early as at week 1 when no significant weight gain and fat changes could be observed, which support that the weight gain seen in IFX treated patients is caused by metabolic changes [Citation24]. Thus, weight gain with TNF inhibitors could be due to an increase in muscle or fat-free mass [Citation30], which is a positive effect, however, other studies have shown an increase in fat mass in patients with CD and other inflammatory diseases [Citation17,Citation32,Citation40], which could increase cardiovascular risk and risk of developing the metabolic syndrome. Body fat percentage estimated by Bioimpedance increases with 3.15% after 6 months compared to baseline values in CD [Citation32]. On the other hand, weight gain has been seen in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and CD without any changes in body composition in response to treatment, suggesting a complex physiological mechanism behind the increase. The weight increase could be explained by the improvements in disease activity and metabolic parameters such as an increase in leptin and therefore a correction of energy imbalance leading to increased physical activity and increased appetite [Citation21,Citation24].

Conclusion

Approximately 60% of infliximab treated Crohn’s disease patients experience weight gain within the first 6 weeks. The weight increment correlates with improvements in inflammatory markers at all time points. The causes of the weight gain need to be further explored, and is probably caused by a combination of reduced inflammatory burden and treatment induced metabolic changes. Further studies on the cause of weight gain are required to better understand the role of TNF-alpha in the observed weight changes.

Authorship statement

Guarantor of article: SA.

Specific author contributions: JL performed the research, undertook the statistical calculations and wrote the paper, CH, ML collected and analyzed the data, AF, UF collected the data, SA designed the research study, collected data and wrote the paper.

All authors approved the final version of the article, including the authorship list.

Acknowledgements

Mirjam Majster, DDS, was helpful with additional statistical computing. Parts of the results have been presented at the ECCO meeting in February 2015, in Barcelona, Spain.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Reich K, Nestle FO, Papp K, et al. Infliximab induction and maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe psoriasis: a phase III, multicentre, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9494):1367–1374.

- Saad AA, Symmons DP, Noyce PR, et al. Risks and benefits of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors in the management of psoriatic arthritis: systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:883–890.

- Scott DL, Kingsley GH. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:704–712.

- Gorman JD, Sack KE, Davis JC. Jr. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis by inhibition of tumor necrosis factor alpha. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(18):1349–1356.

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Deltenre P, de Suray N, et al. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn’s disease: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(6):644–653.

- Yang HZ, Wang K, Jin HZ, et al. Infliximab monotheraphy for Chinese patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo- controlled multicenter trial. Chin Med J. 2012;125:1845–1851.

- Altwegg R, Vincent T. TNF blocking therapies and immunomonitoring in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Mediators Inflammation. 2014;2014:172821.

- Hyams J, Crandall W, Kugathasan S, et al. Induction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to- severe Crohn’s disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(3):863–873.

- Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, et al. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s disease cA2 study group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(15):1029–1035.

- Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398–1405.

- Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. ACCENT I study group. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9317):1541–1549.

- Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):876–885.

- Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2462–2476.

- Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(7):601–608.

- Karmiris K, Paintaud G, Noman M, et al. Influence of trough serum levels and immunogenicity on long-term outcome of adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1628–1640.

- Loftus EV. Jr. Clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: incidence, prevalence, and environmental influences. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1504–1517.

- Renzo LD, Saraceno R, Schipani C, et al. Prospective assessment of body weight and body composition changes in patients with psoriasis receiving anti-TNF-a treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:446–451.

- Gisondi P, Cotena C, Tessari G, et al. Anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha therapy increases body weight in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis: a retrospective cohort study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venerol. 2008;22(3):341–344.

- Saraceno R, Schipani C, Mazzotta A, et al. Effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapies on body mass index in patients with psoriasis. Pharmacol Res. 2008;57:290–295.

- Argiles JM, Lopez-Soriano J, Busquets S, et al. Journey from cachexia to obesity by TNF. Faseb J. 1997;11:743–751.

- Briot K, Garnero P, Le Henanff A, et al. Body weight, body composition, and bone turnover changes in patients with spondyloarthropathy receiving anti-tumour necrosis factor α treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1137–1140.

- Briot K, Gossec L, Kolta S, et al. Prospective assessment of body weight, body composition, and bone density changes in patients with spondyloarthropathy receiving anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha treatment. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:855–861.

- Florin V, Cottencin AC, Delaporte E, et al. Body weight increment in patients treated with infliximab for plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:e186–e190.

- Franchimont D, Roland S, Gustot T, et al. Impact of infliximab on serum leptin level in patients with Crohn’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(6):3510–3516.

- Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, et al. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749–753.

- World Health Organisation Europe: Health topics; BMI. Copenhagen: WHO. 2020 [cited 2020 May 8]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/nutrition/a-healthy-lifestyle/body-mass-index-bmi

- Daperno M, D'Haens G, Van Assche G, et al. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn’s disease: the SES-CD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:505–512.

- Kim MJ, Lee WY, Choi KE, et al. Effect of Infliximab ‘Top-down’ Therapy on weight gain in Pediatric Crohn’s Disease. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:979–982.

- Vadan R, Gheorghe LS, Constantinescu A, et al. The prevalence of malnutrition and the evolution of nutritional status in patients with moderate to severe forms of Crohn’s disease treated with infliximab. Clin Nutr. 2011;30:86–91.

- Diamanti A, Basso MS, Gambarara M, et al. Positive impact of blocking tumor necrosis factor alfa on the nutritional status in pediatric crohn’s disease patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24(1):19–25.

- Nakahigashi M, Yamamoto T. Increases in body mass index during infliximab therapy in patients with Crohn’s disease: an open label prospective study. Cytokine. 2011;56(2):531–535.

- Weise D, Lashner B, Seidner D. Measurment of nutrition status in Crohn’s disease patients receiving infliximab therapy. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23:551–556.

- Haas L, Chevalier R, Major BT, et al. Biologic agents are associated with excessive weight gain in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(11):3110–3116.

- Christian KE, Russman KM, Rajan DP, et al. Gender differences and other factors associated with weight gain following initiation of infliximab: a post hoc analysis of clinical trials. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(1):125–131.

- Koutroubakis IE, Oustamanolakis P, Malliaraki N, et al. Effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition with infliximab on lipid levels and insulin resistance in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:283–288.

- Mahe E, Reguiai Z, Barthelemy H, et al. Evaluation of risk factors for body weight increment in psoriatic patients on infliximab: a multicentre, cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:151–159.

- Tan E, Baker C, Foley P. Weight gain and tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors in patients with psoriasis. Aust J Dermatol. 2013;54:259–263.

- Metsios GS, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Douglas KM, et al. Blockade of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in rheumatoid arthritis: effects on components of Rheumatoid cachexia. Rheumatology. 2007;46(12):1824–1827.

- Marcora SM, Chester KR, Mittal G, et al. Randomized phase 2 trial of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for cachexia in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(6):1463–1472.

- Engvall IL, Tengstrand B, Brismar K, et al. Infliximab therapy increases body fat mass in early Rheumatoid arthritis independently of changes in disease activity and levels of leptin and adiponectin: a randomized study over 21 months. Arhritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R197.

- Brown RA, Spina D, Butt S, et al. Long-term effects of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy on weight in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:455–461.

- Sfriso P, Caso F, Filardo GS, et al. Impact of 24 months of anti-TNF therapy versus methotrexate on body weight in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective observational study. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1615–1618.