Abstract

Objectives

Self-monitoring of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) with the assistant of telemedicine and home-based fecal calprotectin (FC) tests is evolving in the management of IBD. We performed a randomized controlled trial to investigate the compliance and effects of the model IBD-Home in patients with IBD.

Materials and methods

Patients were randomized to IBD-Home + standard care (n = 84) or standard care alone (n = 74). Intervention with IBD-Home included IBDoc® FC test kits and a digital application used for answering symptom questionnaires (Abbvie/Telia). They were instructed to use these on demand during a 12-month period. Data was collected retrospectively from medical records. Patients who completed the intervention were phoned and asked to answer a survey about the experience of IBD-Home.

Results

The compliance to IBD-Home was low (29%). Women were more compliant compared with men (43% vs 17%, p < .001). A significantly higher proportion of patients in the IBD-Home group increased their medical treatment during the study period in comparison to control subjects (33% vs 15% p = .007) and there was an association between an increase in treatment and compliance to IBD home (multivariate odds ratio 3.22; 95th confidence interval 1.04 − 9.95). Overall patients reported a positive experience with slight technical difficulties.

Conclusion

Self-monitoring with home based fecal calprotectin and a digital application was found feasible and appreciated by compliers. Compliance to the IBD-Home model was more common in women and associated with an increased treatment for IBD.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are chronic inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract which primarily affect young individuals. The principal forms of IBD are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [Citation1]. IBDs are characterized by disabling flares with increased inflammatory activity and symptomatic burden and periods of remission [Citation2,Citation3]. As IBD display heterogeneity between patients and over time, individual monitoring is important to provide effective care. Traditionally the monitoring of IBD has focused on scheduled outpatient visits, endoscopies, symptom questionnaires and laboratory tests. The main laboratory test used for monitoring disease activity is fecal calprotectin (FC) [Citation4]. FC is a non-invasive surrogate marker for intestinal inflammation which has a high negative predictive value for IBD [Citation5–7].

Increased incidence [Citation8,Citation9], prevalence [Citation10] and associated costs of IBD [Citation11–13] has led to the development of new monitoring strategies such as telemedicine and self-monitoring [Citation14,Citation15]. Telemedicine is healthcare via technologies such as telecommunication or the internet without the patient and healthcare provider being physically present together [Citation4].

Previous studies have concluded that monitoring of IBD via telemedicine is safe [Citation16,Citation17] and not associated with increased disease activity [Citation18,Citation19] or morbidity [Citation20]. It has been found to be cost-effective [Citation17,Citation21–23] to reduce hospitalizations [Citation24,Citation25] and to improve quality of life [Citation26]. Self-monitoring is a method where patients are provided education and resources that allow them to monitor their condition themselves and contact healthcare in case of increased disease activity [Citation4]. Self-monitoring has been found to be safe, lead to fewer hospital admissions [Citation27] and improve quality of life [Citation28].

A recent development combining these two methods is self-monitoring via Home Based Fecal Calprotectin Tests (HBFCT) [Citation29]. HBFCT are FC tests that can be used by patients at home [Citation30] and which several studies have found correlate with the traditional laboratory FC tests [Citation29,Citation31,Citation32]. Wei et al examined HBFCT combined with digital phone application as a self-monitoring. They found that most patients were satisfied and preferred the set up over traditional monitoring [Citation32]. Puolanne et al evaluated self-monitoring via HBFCT in a recent randomized controlled trial (RCT). While most of patients felt that they could recommend HBFCT to other patients their intervention had low compliance.

Few studies have been conducted on self-monitoring with HBFCT that have compared intervention with a control group. Furthermore, there is no consensus on optimal implementation and the effects of its implementation [Citation29,Citation32–34]. The concept of IBD-Home was developed by Abbvie, Telia, Bühlmann, the Swedish Register of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SWIBREG), patients with IBD and representatives of the Swedish health system (https://www.abbvie.se/om-abbvie/innovation-och-samarbeten/ibd-home.html). Thus in 2018 Region Västerbotten in collaboration with the companies Abbvie and Telia implicated a local HBFCT project using IBD-Home. To test IBD-Home in clinical practice we constructed a randomized controlled trial.

The primary aim of the study was to study acceptance and adherence to the introduction of IBD-Home and factors associated with compliance to the model when introduced in clinical practice. A secondary aim was to compare health care interactions and changes made in medical treatment between patients randomized to the IBD-Home intervention and control persons.

Materials and methods

Inclusion and recruitment of patients with IBD

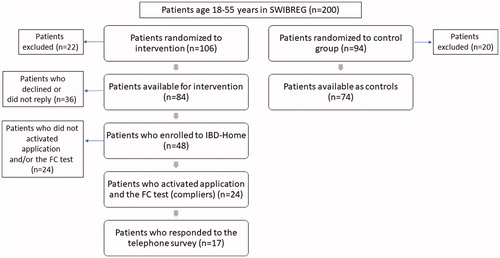

The inclusion criteria for the study was age 18–55 years, living in the catchment area of Umeå University Hospital, Västerbotten county, Sweden and having a verified IBD diagnosis. The exclusion criteria were having moved from the Umeå area or being colectomized due to UC. Two-hundred patients who met the inclusion criteria were randomly selected from the Swedish Inflammatory Bowel Disease Register (SWIBREG) [Citation35] for the study and were randomized by the day in the month they were born (even/uneven) to IBD-Home intervention (even) or to a control group (uneven). Of the 200 patients included in the study 106 were randomized to IBD-Home and 94 patients were included in the control group. Twenty-two patients from the IBD-Home group and 20 patients from the control group were removed due to exclusion criteria, leaving 84 patients in the IBD-Home group and 74 patients in the control group eligible for the study.

The patients randomized to intervention with IBD-Home received a letter explaining the study and offering enrollment by sending an e-mail to the local study coordinator. Those who did not reply to were contacted by phone. Patients who failed to answer or had not seen the letter prior to the call received a second letter. The control group received a letter notifying that they had been included as controls. shows how the patients were recruited for the study.

IBD-Home model

In addition to receiving standard treatment the IBD-Home patients who were enrolled were given written instruction and video instruction how to download and activate a digital phone applicationand how to perform the HBFCT. When properly activated the application was connected to their personal patient ID in SWIBREG. Using the application, the patients could answer the standard SWIBREG symptom questionnaires [Citation35], which includes Short Health Scale-IBD, Harvey Bradshaw Index (CD) and Simple Colitis Clinical Activity Index (UC). In addition, the patients who accepted to participate in the IBD-Home intervention received four Bühlmann HBFCT IBDoc® test kits with instruction manual. They were encouraged to perform FC tests and then insert the FC value in the digital application. The patients were informed that he or she could perform HBFCT and answer questionnaires at any time (both during a suspected flare or to confirm remission) with immediately transformation of information to the hospital clinic. All results from questionnaires and FC tests were automatically uploaded to SWIBREG. Feedback to the patients were given if the patients was showing sign of inflammatory activity by the IBD nurse or the patients doctor. The study period when the patients were eligible to answer questionnaires and perform FC tests was between December 2018 to December 2019. Patients who used the digital application to answer SWIBREG symptom questionnaires at least once and conducted at least one HBFCT were defined as ‘compliers’. ‘Non-compliers’ were defined as all patients who were randomized to IBD-Home without exclusion criteria and who not completed the intervention (patients who were non-adherent, who declined or not responding).

Bühlmann HBFCT IBDoc® test kits

The patient was given both a written and a video instruction manual to perform the HBFCT test. The patient was first asked to download the digital application to their telephone. The test kit includes an extraction device (test pin and tube) and a test cassette. The patient was instructed how to collect stool, using a fecal collection paper sheet and to dip the sampling pin into the stool sample a few times with a twisting motion. The test pin is then placed back into the tube through the upper funnel and then inserted into the test cassette. Using the camera in the smartphone which automatically focus and takes a picture, the image is analyzed through a sophisticated image processor and a quantitative result is calculated by the digital application. The patient receives the result as ‘normal’, ‘moderate’ or ‘high’. The result was also automatically and immediately transferred to the SWIBREG platform where the IBD-home coordinator could read the FC level and contact the patient or the patients doctor when necessary.

Medical records and SWIBREG

Data was collected retrospectively from SWIBREG and medical records of medicine and surgery at Umeå University Hospital. Baseline data collected was IBD type according to the Montreal classification [Citation36], years since diagnosis, medical treatment at inclusion and median FC values (CALPRO®), C-reactive protein and B-Hemoglobin three years prior to inclusion.

To analyze health care interactions during the study, we noted all telephone contacts, health care visits and medical treatment from the medical records. Telephone data included the number of calls with nurses and doctors. Health care visits included the number of outpatient visits, visits to emergency wards or hospitalization and endoscopy visits. To analyze changes in medical treatment during study data on increased treatment and/or reduction of treatment was collected. Increased treatment was defined as prescribing a new drug or increasing dosage of an already prescribed and used drug. Reduction in treatment was defined as stopping or reducing the dosage of a prescribed and used drug.

Telephone survey

In order to evaluate the patient experience of the IBD-Home model we conducted a phone survey. The compliers of IBD-Home model were phoned during working hours and after a brief introduction were asked to answer the IBD-Home phone survey including 7 questions of their experience of IBD-Home (). If willing to participate summarizations of their answers were noted during interviews.

Table 1. Questions at a telephone survey to compliers of IBD-Home.

Statistics

All statistics were calculated in IBM SPSS statistics 26. Differences in scale variables were analyzed with Sharpio-Wilk test for normality and if found normally distributed analyzed with an independent T-test. If found non-normally distributed the scale variable was analyzed with Mann–Whitney U-test. Differences in nominal and ordinal variables were analyzed with Pearson’s χ2-test and Fishers exact test when appropriate. Furthermore, variables for compliance to IBD-Home and increased treatment during study was analyzed with univariate and multivariate binary logistic regression.

Ethics

The study had ethical approval for clinical research from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority and the diary number was 2018/275/31.

Results

Baseline characteristics

There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the patient randomized to IBD-Home and the control group ().

Table 2. Baseline demographics and characteristics of patients at inclusion.

Compliers versus non-compliers to IBD home

Of the 84 patients in the IBD-Home group 47 (56%) accepted to participate and 37 (44.0%) denied participation or failed to respond. Only half (24 out of 47) of the patients who accepted to participate in IBD-Home were adherent to the study intervention and defined as ‘compliers’ in the study. A significant higher proportion of women than men were compliers to the IBD-Home intervention. In a multivariate analysis after adjustment for age at inclusion, years since diagnosis, type of IBD and FC levels prior to inclusion, femal gender still was associated with adherence to the IBD home intervention ().

Table 3. Factors associated with adherence to the IBD-Home model in the patients randomized to IBD-Home. Logistic regression.

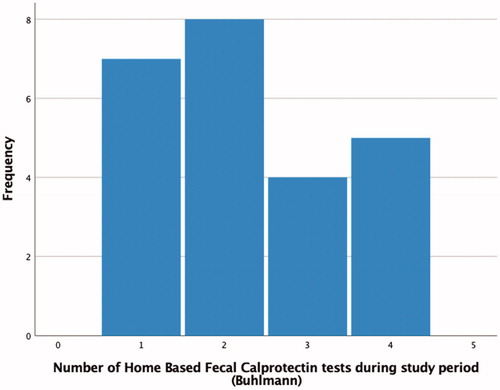

All patients who accepted to participate in the IBD-Home intervention was given 4 HBFCT for the study. Among the 24 compliers only 40 out of 96 (42%) HBFCT was used. The overall amount of FC test performed (HBFCT + FC in standard care) was significantly higher among the compliers in comparison to non-compliers (median number of test 3 (25th–75th percentile 2–5) vs 1 (0–1); p < .001). shows the total number of Bühlmann HBFCT IBDoc® per patient in the intervention group who was compliant to the IBD-Home model.

Health care interactions and medical intervention during the study

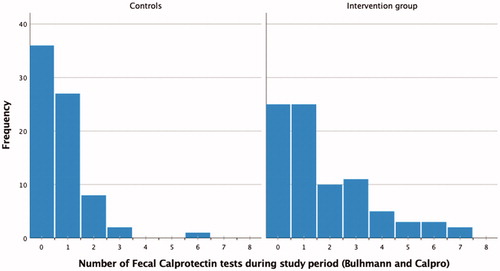

The overall amount of FC test performed (HBFCT + FC in standard care) was significantly higher among the patients randomized to IBD-Home in comparison to the control group during the study period (median number of test 1 (25th–75th percentile 0–3) vs 1 (0–1); p < .001). shows the total number of tests (both Bühlmann HBFCT IBDoc® and CALPRO®) per patient in the intervention and the control group.

Figure 3. The total number of tests (both Bühlmann HBFCT IBDoc® and CALPRO®) per patient in the intervention group (IBD-home model) and in the control group.

There were no significant differences in overall healthcare interactions for IBD (telephone contacts and health-care visits) between the patients randomized to the IBD-Home group and the control group (). However, the compliers had significant more total number of overall health care visits for IBD as well as telephone contacts in comparison to the non-compliers. There were no differences between any subgroup in the number of hospital admission, outpatient visits or endoscopy visits.

Table 4. Healthcare interactions and change in medical treatment during study.

p<0.05 is statistically significant and is marked in bold.

The proportions of patients who during the study period had increased medical treatment was significantly higher in patients randomized to IBD-Home in comparison to controls and significant higher among the compliers in comparison to non-compliers of IBD-Home (). In a multivariate logistic regression of the patients randomized to IBD-Home, adjusted for gender, age at inclusion and FC values prior to inclusion, being adherent to IBD-Home was still associated with increased medical treatment (). There was no difference in the proportions of patients who had reduction in medical treatment during the study period between the IBD-Home group and the control group, and between compliers and non-compliers to IBD-Home.

Table 5. Factors associated with increased medical treatment in the IBD-Home group.

Telephone survey of the patients who were compliers to IBD-Home

Of the 24 compliers, 17 patients (71%) accepted to participated in the phone survey. The most stated reason for participation in IBD-Homewas a positive attitude towards telemedicine (N = 8) and a possibility for more regular monitoring (N = 7). Fifteen of the 17 patients reported a positive experience of IBD-Home however two patients suggested that a more thorough initial training would had been preferable. The digital application and the HBFCT were reported easy to use by most patients (N = 14) and only 3 patients reported minor difficulties in performing the HBFCT. The compliers stated several positive effects of participating in IBD-Home. These included not having to travel to a health care facility for testing (N = 8), having more monitoring of (N = 6), receiving direct feedback of disease activity (N = 4), easier timing of testing with disease activity (N = 3) and better knowledge of their disease (N = 3). Two patients reported that HBFCT was time consuming, but all patients except one had an interest in continuing with IBD-Home. To improve IBD-Home in clinical practice four patients suggested more initial training and two patients suggested more feedback of their reporting and test results.

Discussion

In recent years new self-monitoring strategies for IBD have been implicated to standard care for IBD [Citation4]. The aim of this study was to examine factors associated with compliance to the IBD-Home, a self-monitoring model which included home based FC testing and self-reporting of symptoms via a digital application. In total, only 29% of patients randomized to IBD-Home were compliant to the model. This is far lower than the 12-month compliance found in other IBD telemedicine studies [Citation19,Citation20,Citation24,Citation25,Citation34] showing an adherence rate of 70–90%. However, the compliance rate in our study is comparable with a Finnish study that showed that only 27% had a 12-month compliance of a HBFCT [Citation33]. While there is heterogeneity in study design between these studies, this still indicates that long term patient compliance is lower in HBFCT models than in non-HBFCT models. Like other HBFCT studies we did not find a significant association between FC levels and compliance. The compliers had shorter time from diagnosis than non-compliers but the different was not significant. Perhaps an early introduction of HBFCT models at the time of diagnosis might had improve adherence in our study with an increased number of subjects who become complaint. Perhaps the most importance is the timing when introducing the IBD-Home model. A patient with active disease is probably more motivated than a patient in long term remission. Also, a more thoroughly introduction with direct personal interaction could perhaps had improved the compliance in our study.

Another factor for the low compliance of HBFCT in our study could be that the intervention group also received standard care. For example, most of the patients had scheduled contacts at least once a year and therefor some patients in remission felt that IBD-Home was redundant.

Interestingly, the only factor that was significantly associated with compliance to IBD-Home in our study was female gender. While gender differences in IBD telemedicine compliance has not been reported, there are studies which have found women to be more likely to be engaged in general telemedicine practices compared to men [Citation37,Citation38]. However, there are also studies that have found men with chronic medical conditions [Citation39] or hypertension [Citation40] to be more compliant to self-monitoring telemedicine models than women. As these studies found contradictory results indicate that there is currently no consensus about gender difference in telemedicine compliance.

A secondary aim of our study was to evaluate how IBD-Home model effected the number of health care contacts and the medical treatment for IBD. In the conclusions of previous studies it has been argued that the use of telemedicine reduces health care contacts [Citation17,Citation20,Citation24] and heath care costs [Citation19,Citation23]. Paradoxically, our study showed that the compliers to IBD home had a higher number of health care interactions when compared to both control persons and non-compliers. Interestingly the proportion of patients who received increased medical treatment was significantly higher for IBD-Home compliers than any other group. In comparison previous IBD studies have found no differences in medical treatment [Citation19] or corticosteroid treatment [Citation24] between telemedicine compliers and control. One possible factor for the increased number of health care contacts and increased medical treatment among the compliers of IBD-Home could be that IBD-Home was offered as an additional option to standard care. Also, median FC levels the years before inclusion was higher in the intervention group (although non-significant), reflecting that this group might had higher disease activity at onset. However, there was still an association between complying to the IBD-Home model andincreased medical treatment in the after for controlling for age, gender and FC.

We utilized a phone survey to evaluate the patient experience of IBD-Home model. Overall, the patients reported that IBD-Home was easy to use, had several advantages and wished to continue using IBD-Home which is consistent with results of previous studies [Citation20,Citation24,Citation32,Citation41,Citation42]. Some patients suggested thar more initial training would have been feasible.

We acknowledge that this study had several limitations that could have been improved upon.

Firstly, most patients had an established care for IBD and if only patients at onset had been include the compliance rate and effect of the intervention could had been different. In addition, the IBD-Home group only received an instruction manual (written and video information) for the test kits and no initial training at our clinic. This could have had a negative effect on compliance to the model. However, at the IBD-Home web site there is clear written and video instruction how to use the fecal test and the digital application and most of the compliers reported that the digital application and HBFCT test were easy to use. The duration of the study was only one twelve months long and this could also have had effect on compliance. Perhaps, using a longer study period more patients might had started and had become more used to the IBD-Home model. Lastly, apart from changes in medical treatment we were not able to compare disease activity between the groups. A reason for this was that there was too much missing data on disease activity for the control persons and non-compliers.

In conclusion, as IBD increases worldwide new monitoring strategies are of great importance. Telemedicine and self-monitoring for IBD have proven themselves safe and feasible with several positive effects. Unlike other studies, our study shows that compliance to the IBD-Home model was associated with increased medical treatment and on the short basis with more contacts with health services. The overall low compliance, especially among men, highlights the importance of having optimal strategies when introducing new self-monitoring models. As there is currently limited knowledge about IBD self-monitoring with home-based FC tests more studies are needed to properly determine the optimal implementation of the technology in IBD care, as well as cost effectiveness.

Acknowledgements

We thank the IBD nurses Vivan Brännström and Miriam Westerlund at the Department of Medicine, Umeå University for their meticulous work in conducting the recruitment patients for the IBD home project. We also thank Telia for the cooperation and Marlene Almqvist at Abbvie for providing us manuals for IBD-Home.

Disclosure statement

The implication of the IBD-Home project in Region Västerbotten, Sweden was done in cooperation with the companies Abbvie and Telia. The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Wehkamp J, Gotz M, Herrlinger K, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113(5):72–82.

- Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, et al. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(1):3–11.

- Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, et al. Changes in extent of ulcerative colitis: a study on the course and prognostic factors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(3):260–266.

- Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, IBD guidelines eDelphi consensus group, et al. British society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68(Suppl 3):s1–s106.

- Burri E, Beglinger C. Faecal calprotectin - a useful tool in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13557

- Ikhtaire S, Shajib MS, Reinisch W, et al. Fecal calprotectin: its scope and utility in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(5):434–446.

- Ayling RM, Kok K. Fecal calprotectin. Adv Clin Chem. 2018;87:161–190.

- Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, ECCO -EpiCom, et al. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in europe. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(4):322–337.

- Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769–2778.

- Burisch J, Munkholm P. Inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29(4):357–362.

- Rocchi A, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: a canadian burden of illness review. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(11):811–817.

- Vadstrup K, Alulis S, Borsi A, et al. Cost burden of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in the 10-year period before diagnosis-a danish register-based study from 2003-2015. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;26:1377–1382.

- Vadstrup K, Alulis S, Borsi A, et al. Societal costs attributable to Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis within the first 5 years after diagnosis: a Danish nationwide cost-of-illness study 2002-2016. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:41–46.

- Burisch J, Munkholm P. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(8):942–951.

- Riaz MS, Atreja A. Personalized technologies in chronic gastrointestinal disorders: self-monitoring and remote sensor technologies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(12):1697–1705.

- Aguas M, Del Hoyo J, Faubel R, et al. Telemedicine in the treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40(9):641–647.

- Heida A, Dijkstra A, Muller Kobold A, et al. Efficacy of home telemonitoring versus conventional follow-up: a randomized controlled trial among teenagers with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(4):432–441.

- Cross RK, Cheevers N, Rustgi A, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of home telemanagement in patients with ulcerative colitis (uc HAT). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(6):1018–1025.

- Carlsen K, Jakobsen C, Houen G, et al. Self-managed ehealth disease monitoring in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: a randomized controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:357–365.

- Elkjaer M, Shuhaibar M, Burisch J, et al. E-health empowers patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomised controlled trial of the web-guided 'constant-care' approach. Gut. 2010;59(12):1652–1661.

- Li SX, Thompson KD, Peterson T, et al. Delivering high value inflammatory bowel disease care through telemedicine visits. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(10):1678–1681.

- Jackson BD, Gray K, Knowles SR, et al. Ehealth technologies in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. ECCOJC. 2016;10(9):1103–1121.

- Del Hoyo J, Nos P, Bastida G, et al. Telemonitoring of crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis (teccu): cost-effectiveness analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(9):e15505

- de Jong MJ, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Romberg-Camps MJ, et al. Telemedicine for management of inflammatory bowel disease (myibdcoach): a pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10098):959–968.

- Cross RK, Langenberg P, Regueiro M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of telemedicine for patients with inflammatory bowel disease (tele-ibd). Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:472–482.

- Aguas Peris M, Del Hoyo J, Bebia P, et al. Telemedicine in inflammatory bowel disease: opportunities and approaches. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(2):392–399.

- Robinson A, Thompson DG, Wilkin D, et al. Guided self-management and patient-directed follow-up of ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358(9286):976–981.

- Tu W, Xu G, Du S. Structure and content components of self-management interventions that improve health-related quality of life in people with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(19-20):2695–2709.

- Vinding KK, Elsberg H, Thorkilgaard T, et al. Fecal calprotectin measured by patients at home using smartphones - a new clinical tool in monitoring patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(2):336–344.

- Elkjaer M, Burisch J, Voxen Hansen V, et al. A new rapid home test for faecal calprotectin in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:323–330.

- Heida A, Knol M, Kobold AM, et al. Agreement between home-based measurement of stool calprotectin and ELISA results for monitoring inflammatory bowel disease activity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(11):1742–1749.e2.

- Wei SC, Tung CC, Weng MT, et al. Experience of patients with inflammatory bowel disease in using a home fecal calprotectin test as an objective reported outcome for self-monitoring. Intest Res. 2018;16(4):546–553.

- Puolanne AM, Kolho KL, Alfthan H, et al. Is home monitoring of inflammatory bowel disease feasible? A randomized controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(7):849–854.

- Ankersen DV, Weimers P, Marker D, et al. Individualized home-monitoring of disease activity in adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease can be recommended in clinical practice: a randomized-clinical trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(40):6158–6171.

- Ludvigsson JF, Andersson M, Bengtsson J, et al. Swedish inflammatory bowel disease register (swibreg) - a nationwide quality register. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(9):1089–1101.

- Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, et al. The montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55(6):749–753.

- Baumann E, Czerwinski F, Reifegerste D. Gender-specific determinants and patterns of online health information seeking: results from a representative German Health Survey. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(4):e92

- Escoffery C. Gender similarities and differences for e-health behaviors among U.S. Adults. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24(5):335–343.

- Celler B, Argha A, Varnfield M, et al. Patient adherence to scheduled vital sign measurements during home telemonitoring: Analysis of the intervention arm in a before and after trial. JMIR Med Inform. 2018;6(2):e15.

- Kerby TJ, Asche SE, Maciosek MV, et al. Adherence to blood pressure telemonitoring in a cluster-randomized clinical trial. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich)). 2012;14(10):668–674.

- Cross RK, Arora M, Finkelstein J. Acceptance of telemanagement is high in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(3):200–208.

- Cross RK, Finkelstein J. Feasibility and acceptance of a home telemanagement system in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a 6-month pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(2):357–364.