Abstract

Background

There is a need for easy-to-use patient-reported outcome measures (PROMS) in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) practice. The ‘IBD-control’ is a short IBD-specific questionnaire capturing disease control from the patient’s perspective. The International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) recommends the use of the IBD-control even though it has only been validated in the United Kingdom. We aimed to cross-culturally translate and validate the IBD-control in the Netherlands using IBDREAM, a prospective multicentre IBD registry.

Methods

Lack of ambiguity and acceptability were verified in a pilot patient group (n = 5) after forward-backward translation of the IBD-control. Prospective validation involved completion of the IBD-control, Short Form-36, short IBDQ and disease activity measurement by Physician Global Assessment (PGA) and Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index or Harvey-Bradshaw Index. Test–retest (2-week repeat) was used for measuring reliability.

Results

Questionnaires were completed by 998 IBD patients (674 Crohn’s disease, 324 ulcerative colitis). Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.82 for the sub-group of 8 questions (IBD-control-8-sub-score). Mean completion time was 105 s. Construct validity analyses demonstrated moderate-to-strong correlations of the IBD-control-8-subscore and the other instruments (0.49-0.81). Test–retest reliability for stable patients was high (intraclass correlation coefficient 0.95). The IBD-control-8-subscore showed good discriminant ability between the PGA categories (ANOVA, p<.001). Sensitivity to change analyses showed large effect sizes of 0.81-1.87 for the IBD-control-8 subscore.

Conclusions

These results support the IBD-control as a rapid, reliable, valid and sensitive instrument for measuring disease control from an IBD patient’s perspective in the Netherlands.

Introduction

An important goal of treatment in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is to achieve and maintain disease control. The optimal strategy to identify patients with good disease control in clinical practice is still under debate, and there is need for easy-to-use screening instruments to reliably capture disease control [Citation1]. Nowadays, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are used to measure the impact of chronic diseases on quality of life from the patients’ perspective. Although different PROMs are validated, translated and used in clinical trials, none is commonly applied in daily clinical practice. This might be explained in part due to the fact that all these instruments do not accurately capture the patients’ view on disease control. In contrast, these PROMs focus mainly on complaints, sometimes in combination with quality of life, like the lengthy SF-36 [Citation2], the IBDQ and its shorter version, the short IBDQ [Citation3,Citation4]. More recently, several new PROMs have been developed [Citation1,Citation5,Citation6]. A promising instrument to capture the patient’s perspective on disease control is the IBD-control questionnaire, which was recently developed and validated in the United Kingdom in collaboration with patients [Citation1]. The authors previously showed that the IBD-control is a rapid measurement tool with the ability to identify patients with good disease control.

The use of the IBD-control is recommended by the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM). However, before using a questionnaire like the IBD-control in other countries, several steps have to be taken. As it has been developed and validated in an English-speaking culture, it first requires forward-backward translation. However, it is known that patients’ responses to such instruments are dependent on underlying cultural trends, so that the sole translation into another language is not sufficient for its use. Re-establishing the validity, reliability and responsiveness within the new national context is required. Therefore, the aim of our study was to cross-culturally translate and adapt the IBD-control for use in Dutch patients, and assess its reliability, validity and responsiveness.

Materials and methods

Translation and back translation of IBD-control

Cross-cultural adaptation was performed in two sequences, following established guidelines [Citation7]. The first step involved the translation into Dutch by a panel of an expert IBD physician (M.R.) and a health psychologist (E.T.) until a consensus translation was reached. Next, back-translation was performed by two bilingual translators and compared with the original IBD-control. Subsequently, the prefinal version was tested for lack of ambiguity in 5 IBD patients (1 male, 4 female; age range 23-67 years; disease duration 1-12 years) using the Three-Step Test Interview method [Citation8]. Based on these interviews, no alterations of the prefinal version were needed. The final version of the Dutch translation of the IBD-control is included in Supplementary File A.

Data collection

We used IBDREAM, a large multicentre prospective IBD registry in the Netherlands, to collect all outcomes of our study. Since 2016, IBDREAM systematically collects medical data from IBD patients in four non-academic and one academic hospital, as previously described [Citation9]. All patients with an established diagnosis of Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) or IBD unclassified (IBD-U) were included. Patients with IBD-U were included in the analyses of UC. Non-Dutch speaking subjects and patients with cognitive impairment or serious psychiatric diseases were excluded. All patients were recruited prior to their routine outpatient visits or during other treatment-related visits (e.g., infusion visit for biologics). They were asked to complete the questionnaires online in IBDREAM prior to their visit. During the study period, physicians were blinded for the results of the questionnaires at the moment of assessing the other health scores. Baseline and follow-up results were collected from moment of inclusion in IBDREAM until June 2018. In order to assess test–retest reliability, a subset of patients (n = 46) were asked to complete the questionnaires a second time after 2 weeks.

Measures

Clinical measures included the assessment of disease activity (Harvey Bradshaw Index (HBI) for CD [Citation10] or Short Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) [Citation11] for UC and IBD-U and the Physician Global Assessment (PGA) of disease activity (remission, mild, moderate or severe activity). Patients completed the IBD-control [Citation1], the short IBDQ [Citation4] and the Short Form-36 version 2 [Citation2].

IBD-control

The IBD-control is a short disease-specific questionnaire for patients with IBD [Citation1]. It measures the overall disease control during the last two weeks and consists of five sections, including 13 categorical items and a visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (worst possible disease control) to 100 (best possible disease control). Sections 1 and 3 are related to disease control during the past 2 weeks and consist of eight questions: the IBD-control-8. Section 2 addresses changes of bowel symptoms and section 4 evaluates additional treatment-related questions, such as side effects or difficulties using medication. A three-point scale is provided for each item (‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘not sure’ or regarding to changes of bowel symptoms: ‘better’, ‘no change’ or ‘worse’). The items of the IBD-control-8 are scored as follows: least advantageous answer: 0 points, intermediate answer: 1 point, and most advantageous answer: 2 points, adding up to a total IBD-control-8 subscore ranging from 0 points (worst control) to 16 points (best control).

Short IBDQ

The short IBDQ [Citation4] is a short form of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ) [Citation3,Citation12] to measure disease-specific quality of life with 10 items answered on a seven-point scale. Total quality of life scores was calculated ranging from 7 (poorest quality of life) to 70 (most optimal quality of life).

SF-36 v2

The SF-36 version 2 measures generic health-related quality of life with 36 items [Citation13,Citation14]. For this study, we used two higher-order summary scores, the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental summary score (MCS). These summary scores are standardized with normative data from the general population of the United States in 1998 with a mean score of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10.

Psychometric evaluation of the IBD-control

The internal consistency of the IBD-control-8 subscore was assessed using Cronbach’s α [Citation15]. A score higher than 0.70 was considered as a desirable threshold, values higher than 0.90 are suggestive of excessive overlap or redundancy between the categorical items. The item-total correlation was calculated to test whether the individual items correlated with the total. A score >0.3 is considered desirable [Citation16].

In patients with a stable disease status, we analysed test–retest reliability with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). A subset of patients was asked to complete the set of questionnaires two weeks apart. We identified patients with no change in disease status (transition question (question 2) of the IBD-control answered as ‘no change’ and ≤10 point change on the short-IBDQ total score, following the original study of Bodger et al. [Citation1]).

The construct validity of the IBD-control was assessed by determining Spearman’s correlation coefficients of the scores of the IBD-control-8 with quality of life scores (derived from the SF-36 and the short-IBDQ) and with clinical disease activity (the PGA and rating scores from the HBI/SCCAI). We anticipated moderate (>.30) to strong (>.50) correlations with quality of life and with clinical disease activity. Furthermore, we expected correlations with disease-specific quality of life (short-IBDQ) to be stronger than with generic quality of life (SF-36 MCS and PCS). Results of questionnaires and clinical measures were excluded if they were not measured within the same week. We performed subgroup analyses with inclusion of exclusively the questionnaires completed within one day.

We tested the discriminant ability to assess whether the IBD-control differentiates between groups of patients with different disease activity. Therefore, we compared patients with well-controlled disease and patients with insufficient or poor disease control, defined as a PGA of ‘remission’ versus ‘mild’ or versus a combined ‘moderate’/‘severe’ disease activity. Differences between the three disease states were tested with ANOVA analysis of variance with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple testing.

The responsiveness was tested by measuring change scores between two visits in IBD-control-8 subscore compared with change scores of short IBDQ and PGA. Next, we calculated the effect size (size of change scores/SD of baseline score) and the standardized response mean (size of change scores/SD of change scores). An effect size <0.2 was considered small, 0.5 as medium and ≥0.8 as large.

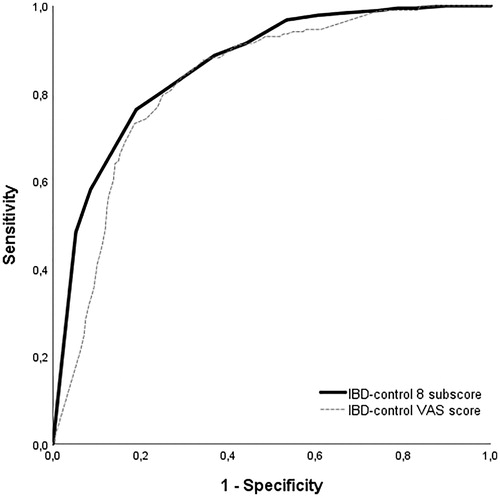

Ability to identify patients with good disease control

To assess the ability of the IBD-control to identify patients with good disease control, receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis was used. We defined a state of ‘quiescent’ disease using a combination of the following parameters: PGA of ‘remission’, HBI score < 5 for CD or a SCCAI score < 4 for UC, no escalation of IBD medication, no hospital admission, not receiving oral corticosteroid therapy, not awaiting surgical treatment, short IBDQ score >53 [Citation17] and no reporting of bowel symptoms getting worse in the past two weeks (IBD-control Q2). We decided that the optimum cut-off score of the IBD-control-8 should have a high specificity (≥80%) to reduce the risk of false positive individuals (assessing a non-quiescent patient as quiescent). Next, the cut-off value with the highest specificity × sensitivity was selected. To analyse discriminative accuracy, the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. An AUC of 0.7–0.9 indicates moderate accuracy, and an AUC >0.9 indicates high accuracy [Citation18].

Statistics

Continuous outcomes are presented as means including SD if normally distributed and as medians with interquartile range (IQR) if non-normally distributed. Data analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical software (version 22, IBM, Chicago, IL).

Ethical considerations

The IBDREAM registry was approved by the medical ethical committee (2015-2245) and the study protocol by the ethical committee of the faculty Behavioural, Management and Social Sciences of the University of Twente (16378). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Results

Patient characteristics

summarizes the baseline characteristics of the patients who completed the IBD-control at baseline. A total of 998 patients completed the questionnaires, 674 patients with CD, 324 with UC. Median time of completion was 105 (74–152) seconds, and the completion rate of patients who started the questionnaire was 99.7% (998/1001).

Table 1. Characteristics of the 998 inflammatory bowel disease patients with completed questionnaires.

Internal consistency

We used Cronbach’s alpha statistics to assess internal consistency of the IBD-control-8. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82 for the IBD-control-8 questions in both CD and UC. Item total correlations of individual items ranged from 0.38 to 0.66 (). If the question with the correlation of 0.38 (Q3e) would be dropped, Cronbach’s alpha of the IBD-control would remain 0.82. Mean time between completion of questionnaires and clinical assessment by the physician was 0.8 (±5.6) days.

Table 2. Item-total correlation of each individual question in de IBD-control-8.

Test–retest reliability

We assessed the reliability by a test–retest approach in a set of 46 patients who completed the questionnaires 2 weeks apart. Of the 46 patients who completed both questionnaires, 28 patients reported no change in disease activity over the past two weeks (Q2). In these 28 patients, there was no significant difference between VAS scores or IBD-control-8 subscores. The mean scores were respectively 12.50 (±4.54) versus 12.54 (±4.11) for the IBD-control-8 (p=.98) and 77.43 (±21.43) versus 81.36 (±20.04) for the VAS score (p=.48). The intra-class correlation was 0.85 for the IBD-control VAS score and 0.93 for the IBD-control-8 subscore.

Construct validity

We found significant moderate-to-strong correlations between the IBD-control-8 subscores and the disease activity and quality of life measures (). As hypothesized we found stronger correlations of IBD-control with disease-specific QoL (SIBDQ) in UC patients than with generic health-related QoL (SF-36). Subgroup analyses with inclusion of exclusively the questionnaires completed within one day of the visit to the clinic yielded similar results (Supplementary File B). The correlation of the IBD-control-8 and other measures in patients with a stoma and patients with (a history of) fistula is shown in Supplementary File B. We repeated all analyses without the patients with a stoma. This led to similar results.

Table 3. Construct validity.

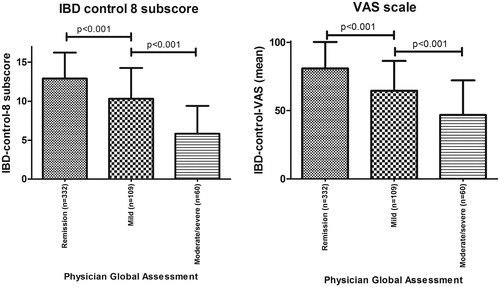

Discriminant ability

As expected, mean IBD-control-8 subscore and VAS score differed significantly between groups with remission, mild and moderate/severe activity according to the PGA. Mean IBD-control-8 subscores were 12.9 (±3.3), 10.3 (±3.9) and 5.8 (±3.6) in patients with remission, mild and moderate/severe (combined) disease activity, respectively. Mean VAS scores were respectively 81 (±19.4), 65 (±21.8) and 47 (±25.3) ().

Responsiveness

Responsiveness analyses showed large effect sizes ranging from 0.81 to 1.87 of the IBD-control-8 subscore (). The effect size of the IBD-control VAS score in the group of patients that improved conform the PGA was small-medium. As expected, the effect size of IBD-control-8 subscore and the IBD-control VAS score in patients with no change on PGA or SIBDQ scores was low. Mean time between subsequent questionnaires was 179 (±83) days.

Table 4. Responsiveness analyses for the IBD-control-8 subscores and VAS scores in patients who improved or worsened according to the short IBDQ and the Physician Global Assessment.

Identifying quiescent patients

A total of 455 patients had simultaneous complete results of (1) HBI/SCCAI, (2) PGA and (3) IBD-control and SIBDQ questionnaires. In total, 48 of 119 (40%) UC and 138 of 338 (41%) CD patients could be categorized as ‘quiescent’ according to our pre-specified criteria. The ROC showed an optimal cut-off point of IBD-control-8 subscore of 14 points (UC: sensitivity 72.9%, specificity 84.5%; CD: sensitivity 73.9%, specificity 81.4%). The AUC was 0.86 for both UC and CD (). A cut-off of 85 on the IBD-control VAS score had a 73.1% sensitivity and 81.3% specificity. Of the 37 patients who scored 14 or higher but did not meet our ‘quiescent’ criteria, no patient needed treatment escalation (i.e., prednisone, start of new medication, surgery) or was hospitalised. Reasons for not meeting the quiescent criteria while scoring >14 on the IBD-control included mild disease according to the PGA (n = 28), a HBI > 4 (n = 5), a short IBDQ score <53 (n = 3) or reporting of worsening of bowel symptoms in the past 2 weeks (n = 1). A total of 200/455 (44%) patients had an IBD-control-8 subscore of ≥14 points.

Discussion

We translated and cross-culturally validated the IBD-control in a large cohort of Dutch patients with CD and UC. This study provides further evidence for the internal consistency, reliability, construct validity, responsiveness and discriminant ability of the IBD-control, supporting implementation and use in daily IBD practice.

In line with the original study of the IBD control, we observed a good acceptability and internal consistency of the IBD-control in this large cohort of 998 IBD patients who completed the questionnaire. The good acceptability is demonstrated by the short completion time and high completion rates (99.7%). The internal consistency of IBD-control-8 was similar with the English version of IBD-control (Cronbach’s alpha 0.82 versus 0.86).

Our Dutch translation of the IBD-control also proved to be a reliable and valid tool. The validity of the IBD-control questionnaire was assessed by comparing the IBD-control-8 and VAS scores with independent external measures of patient health status. We expected good self-reported disease control to be associated with higher quality of life scores and lower scores on disease activity indices. Indeed, we found moderate to strong correlations between the IBD-control scores and disease activity (SCCAI/HBI and PGA) as well as quality of life measures. The finding that the IBD-control is a reliable tool in both CD and UC patients as well as in IBD patients with a stoma or fistula demonstrates that the IBD-control can be used in different subgroups of IBD patients. Furthermore, as expected we found self-reported disease control to be stronger correlated with disease specific quality of life (SIBDQ) than with generic quality of life (SF36). Previously, two conference abstracts from Ireland and Portugal including small patient samples (<80 patients) reported similar results [Citation19,Citation20].

Responsiveness analyses showed that the IBD-control-8 subscore was responsive to change. However, the IBD-control VAS score was only slightly higher in the patients with improved PGA. This might in part be explained by the small numbers of patients and the wide variation in VAS scores. In addition, it might be difficult for patients to score their disease control on a VAS. Based on these results, we would recommend using the IBD-control-8 subscore instead of the IBD-control VAS in clinical practice for the purpose of detecting a change in disease control.

A recent meta-analysis described the potential of electronic health for promoting self-management and reducing the impact of the burden of IBD on resources [Citation21]. PROMs play an important role in electronic health. There already exist many PROMs that can be used to describe the level of complaints, like the PGA, HBI/SCCAI and SF-36. More recently, a DELPHI consensus of IBD experts resulted into the development of the IBD disk [Citation5]. This tool can be used to illustrate the burden of IBD on different health domains. A strength of the IBD-control is that it is developed in collaboration with patients. While most PROMs in IBD measure the burden or the level of complaints, the IBD-control captures the patient’s perception of their disease control.

The IBD-control may be useful in clinical practice, as it is a short questionnaire that has the ability to identify patients who are in a ‘quiescent’ state, defined using a combined outcome of PGA, disease activity indices and treatment outcomes [Citation1]. This has important clinical implications, as patients with a ‘good’ disease control might not need their face-to-face appointment with the clinician. In contrast to the original study, we found an optimal cut-off at 14 points on the IBD-control-8 subscore (original study: 13 points). We hypothesize that, apart from cross-cultural differences, the use of the validated Dutch version of the short IBD-Q score instead of the Anglicised UK-IBD-QoL score as one of the criteria of ‘quiescent disease’ may have contributed to this difference. In addition, we used an electronic version of the IBD-control whereas in the original study a paper version was used. However, in general, it is believed that PROMs administered on paper are quantitatively comparable with measures administered on an electronic device [Citation22]. In addition to the ability to detect patients with ‘quiescent disease’, the IBD control may stimulate patient-empowerment by capturing the topics that patients want to discuss during their next outpatient visit.

The results of our study provide further evidence of the reliability and validity of the IBD-control. In addition, our results suggest that the IBD-control can be used as a patient-reported tool in triaging IBD patients in addition to regular care in the Netherlands. This could potentially lead to a reduction in the number of regular visits to the outpatient clinic in patients with quiescent disease.

Strengths of our study include the rigorous approach of translation and validation in a prospective multicentre setting, including a large number of patients from both academic and non-academic hospitals. This study also comes with limitations. There is always a certain degree of selection bias in patients willing to complete questionnaires or participating in a registry such as IBDREAM. In addition, the proportion of patients using biological therapy was high, since this was the initial focus at the initiation of the IBDREAM registry. However, our patient cohort was large and contained patients with a wide range of disease activity and manifestations. Second, responsiveness analyses were performed in a relatively small group of patients. However, even in this small group, the IBD-control-8 proved to be responsive with effect sizes >0.81.

Conclusions

In conclusion, in a large prospective multicentre cohort, the Dutch version of the IBD-control showed to be a reliable and valid tool to capture the patient’s perspective on disease control. Moreover, using a cut-off value of 14 points on the IBD-control-8 subscore, the questionnaire was able to identify patients with quiescent disease, allowing it to be a potential and rapid tool for identifying IBD patients with good disease control in regular IBD care in the Netherlands.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (458.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients, research nurses and inflammatory bowel disease gastroenterologists of the five departments of gastroenterology and hepatology in the Netherlands for their participation in the data collection.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bodger K, Ormerod C, Shackcloth D, et al. Development and validation of a rapid, generic measure of disease control from the patient's perspective: the IBD-control questionnaire. Gut. 2014;63(7):1092–1102.

- Ware JE Jr., Kosinski MA, Dewey JE. How to score version 2 of the SF-36® health survey. Lincoln, R: QualityMetric Inc.; 2000.

- Guyatt G, Mitchell A, Irvine EJ, et al. A new measure of health status for clinical trials in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96(3):804–810.

- Irvine EJ, Zhou Q, Thompson AK. The Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire: a quality of life instrument for community physicians managing inflammatory bowel disease. CCRPT Investigators. Canadian Crohn's Relapse Prevention Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91(8):1571–1578.

- Ghosh S, Louis E, Beaugerie L, et al. Development of the IBD disk: a visual self-administered tool for assessing disability in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(3):333–340.

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cieza A, Sandborn WJ, et al. Development of the first disability index for inflammatory bowel disease based on the international classification of functioning, disability and health. Gut. 2012;61(2):241–247.

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186–3191.

- Hak T, van der Veer K, Jansen H. The Three-Step Test-Interview (TSTI): an observation-based method for pretesting self-completion questionnaires. Surv Res Methods. 2008;2(3):143–150.

- de Jong ME, Smits LJT, van Ruijven B, et al. Increased discontinuation rates of anti-TNF therapy in elderly inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:888–895.

- Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn's-disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1(8167):514.

- Walmsley R, Ayres R, Pounder R, et al. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43(1):29–32.

- Russel MG, Pastoor CJ, Brandon S, et al. Validation of the Dutch translation of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ): a health-related quality of life questionnaire in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 1997;58(3):282–288.

- Ware JE Jr. SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3130–3139.

- Bullinger M, Alonso J, Apolone G, et al. Translating health status questionnaires and evaluating their quality: the IQOLA Project approach. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(11):913–923.

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334.

- Field AP. 2014. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS. London: Sage Publications.

- Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Barton JR, et al. The short inflammatory bowel disease questionnaire is reliable and responsive to clinically important change in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(10):2921–2928.

- Swets JA. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 1988;240(4857):1285–1293.

- Keogh A, Burke M. N809 IBD control questionnaire: validation and evaluation as part of a virtual biologic clinic in Galway University Hospital, Ireland. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(Suppl. 1):S495–S496.

- Ribeiro F, Fernandes C, Silva J, et al. P370. IBD-Control Questionnaire: validation and evaluation in clinical practice. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9(Suppl. 1):S264.

- Jackson BD, Gray K, Knowles SR, et al. EHealth technologies in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(9):1103–1121.

- Muehlhausen W, Doll H, Quadri N, et al. Equivalence of electronic and paper administration of patient-reported outcome measures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies conducted between 2007 and 2013. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(1):167.