Abstract

Background

Vitamin D deficiency is a common finding in chronic liver disease. It has also been linked to the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, hepatic fibrogenesis, decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Aims

We analyzed whether serum vitamin D is associated with incident advanced liver disease in the general population.

Methods

Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D was measured in 13807 individuals participating in the Finnish population-based health examination surveys FINRISK 1997 and Health 2000. Data were linked with incident advanced liver disease (hospitalization, cancer or death related to liver disease). During a follow-up of 201444 person-years 148 severe liver events occurred. Analyses were performed using multivariable Cox regression analyses.

Results

Vitamin D level associated with incident advanced liver disease with the hazard ratio of 0.972 (95% confidence interval 0.943-0.976, p < .001), when adjusted for age, sex, blood sampling season and stratified by cohort.The association remained robust and significant in multiple different adjustment models adjusting sequentially for 22 potential confounders.

Conclusion

Low vitamin D level is linked to incident advanced liver disease at population level.

Introduction

Vitamin D deficiency is a common finding in chronic liver disease [Citation1,Citation2], and implicated in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD; now also known as metabolic-dysfunction associated fatty liver disease), hepatic fibrogenesis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [Citation1]. In addition, lower serum vitamin D levels are associated with higher Child-Pugh scores in alcohol-related liver disease (ALD), and vitamin D supplementation decreases this score [Citation3]. Furthermore, severe vitamin D deficiency predicts hepatic decompensation in liver cirrhosis [Citation4].

Because the majority of studies on the link between vitamin D and liver disease come from patient cohorts, we carried out a prospective study on the association between serum vitamin D level and incident advanced liver disease in two well-characterized and representative general population cohorts.

Methods

Participants of the FINRISK 1997 and Health 2000 (2000–2001) health-examination surveys in Finland with baseline serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) concentrations were included in this study. The FINRISK 1997 and Health 2000 health-examination cohorts are considered representative of the Finnish adult population, and the studies were coordinated by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (previously National Public Health Institute). The study protocols used in both studies have been published previously in detail [Citation5,Citation6]. The blood samples collected at baseline were handled using a standardized protocol.

The study participants were linked with national health registers until 2015 for advanced liver disease (requiring hospital admission, causing liver cancer or liver-related death) as previously described [Citation7].

Follow-up data were obtained from several national registers through linkage using the unique personal identity code assigned to all Finnish residents. Data for hospitalizations were obtained from the Care Register for Health Care (HILMO), which covers all hospitalizations in Finland since 1969. One or several ICD-diagnoses are assigned to each hospitalization at discharge; these diagnosis codes are systematically recorded in the HILMO register. Data for malignancies were obtained from the Finnish Cancer Registry, with nationwide cancer records since 1953. Vital status and cause of death data were obtained from Statistics Finland. In Finland, each person who dies is by law assigned a cause of death to the official death certificate, issued by the treating physician based on medical or autopsy evidence, or forensic evidence when necessary; the death codes are then verified by medical experts at the register and recorded according to systematic coding principle. Data collection to all these registries is mandatory by law and general quality is consistent and virtually 100% complete [Citation8,Citation9]. Follow-up was until the first liver event or death, until December 2015 or until emigration.

Regarding liver death, outcome events comprised ICD10 codes K70-K77 and C22.0, in line with previous studies [Citation7]. Regarding hospitalization, we included events with the following ICD codes reflective of advanced liver disease, cirrhosis or equivalent: K70.1-K70.4, K70.9, K72.0, K72.1, K72.9, K74.0-K74.2, K74.6. Liver cancer was defined by code C22.0. We excluded those with a baseline diagnosis of liver disease in any registry or chronic viral hepatitis at baseline or during follow-up.

The season of withdrawing the samples for serum vitamin D analyses was November-March in 91% and 65% of cases, and April-October in 9% and 35% of cases in FINRISK 1997 and Health 2000, respectively. 25(OH)D was measured with ARCHITECT system (Abbott Diagnostics) in FINRISK 1997 [Citation10], and with radio immunoassay (DiaSorin) in Health 2000 [Citation11].

The association of vitamin D level on the risk for liver events was analyzed by multivariable Cox regression analyzes stratified by cohort. Confounders included sex, age, education, employment, marital status, leisure-time physical activity, smoking status, number of cigarettes per day, alcohol use, binge drinking, body mass index, waist-hip-ratio, type 2 diabetes, homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome components, fatty liver index, cholesterol (total, LDL, HDL), triglycerides, gamma-glutamyltransferase, and blood sampling season (November-March vs. April-October). The functional form of the association between vitamin D level and incident liver events in the Cox model was evaluated using restricted cubic splines. p < .05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed with R software version 3.6.0.

Results

The combined data included 13807 subjects with 148 incident severe liver events during a 201444 person-year follow-up. From the observed 148 advanced liver disease cases, 67 were from Health 2000 and 81 from FINRISK 1997, respectively. Median follow-up was overall 13.4 years (interquartile range, IQR 13.0–17.8); for the Health 2000 cohort 13.1 years (IQR 12.9–13.2), and for the FINRISK 1997 cohort 17.8 years (IQR 17.8–17.9), respectively. Among the individuals who developed incident advanced liver disease during follow-up, the median time to first record of liver disease was 9.5 years from baseline (IQR 4.9–12.3).

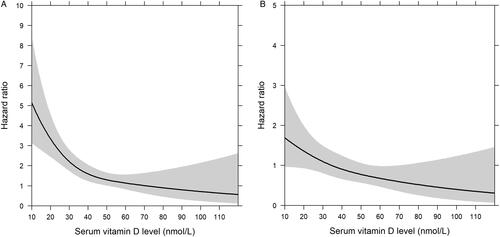

Characteristics are shown in . Vitamin D level was associated with incident advanced liver disease (): the hazard ratio (HR) per 1 nmol/L was 0.972 (95% CI 0.943–0.976, p < .001), when adjusted for age, sex and blood sampling season, and stratified by cohort. The HR remained fairly stable, varying between 0.969 and 0.984 in other multivariate models (). When excluding the first 3 years (23 cases occurred within 3 years from study baseline, and 125 beyond 3 years) of follow-up to minimize possible reverse causation, the adjusted HR remained significant (HR 0.988, 95% CI 0.976–1.000, p = .049). After exclusion of individuals with incident advanced liver disease within 3 years after baseline, the annual event rate was 77.9 per 100 000 person-years.

Figure 1. The functional form of the association between serum vitamin D level and incident advanced liver disease by Cox regression analysis with vitamin D modelled non-linearly using restricted cubic splines, and adjusted for age, sex and season and stratified by cohort (A), or age, sex, waist-hip ratio, body-mass index, type 2 diabetes, alcohol use (grams per week), smoking (current, former, never), exercise, season and stratified by cohort (B).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the whole study population.

Table 2. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for incident severe liver events (hospitalization, liver cancer or liver deaths) according to serum vitamin D based on Cox regression analyses in the combined FINRISK 1997 and Health 2000 cohorts. Cox regression analyses are stratified by cohort.

When including milder forms of liver disease in the outcome events (245 events, ICD10: K70-K77), the HR for vitamin D level was 0.984 (95% CI 0.975–0.993, p < .001).

Discussion

We found that a low serum vitamin D level predicts incident liver-related outcomes in the general population, and this association remained robust and significant in different multivariable models. The risk for advanced liver disease started to increase substantially at vitamin D levels below 40–50 nmol/L, which resembles the cut-off for inadequate levels according to Institute of Medicine [Citation12] (). Our findings were in line with one previous Danish population-based study, where the authors studied the association between vitamin D status and incident liver disease [Citation13]. However, we focused on clinically more relevant advanced liver diseases (e.g. cirrhosis, liver failure and HCC), whereas the Danish study included also milder liver diseases, including for example fatty liver [Citation13]. We adjusted our analyses for multiple social, lifestyle and metabolic-health factors. We did not adjust for vitamin D supply from diet, but the previous study did not find confounding effect from unhealthy diet (based on Healthy Food Index) to the association between vitamin D and liver disease [Citation13]. Vitamin D levels have been associated with several health indicators [Citation11], and therefore, despite our adjustments for various confounders, residual confounding cannot be excluded. Thus, it is possible that vitamin D level at the population level reflects overall health and healthy habits.

Previously, low vitamin D levels have been associated with chronic liver diseases [Citation1,Citation2], and also with HCC risk in cirrhosis [Citation1]. Interestingly, vitamin D has reported to inhibit proliferation and expression of fibrotic markers in hepatic stellate cells in rats [Citation14]. The mechanism of the role of vitamin D on fatty liver disease is unknown, but vitamin D supplementation has distinct effects on fecal microbiota [Citation15]. In addition, it reduces inflammatory cytokines [Citation16], and decreased triglyceride levels in patients with metabolic syndrome [Citation17]. However, vitamin D supplementation for those with NAFLD have not been proved to decrease liver enzymes, although it might improve lipid profile and inflammatory mediators [Citation18]. Furthermore, vitamin D supplementation has been reported to decrease Child-Pugh scores in patients with ALD [Citation3]. Thus, vitamin D supplementation in vitamin D deficiency might be beneficial for the liver. However, overall quality of evidence supporting vitamin D supplementation to reduce the risk of chronic liver disease or its progression is still very low [Citation19], and further interventional studies are needed. Repeated measurements of vitamin D level would have provided additional information to our study, but unfortunately such data were unavailable.

In conclusion, a low serum vitamin D level was associated with an increased risk for incident advanced liver disease in the general population.

| Abbreviations | ||

| ALD | = | alcoholic liver disease |

| HCC | = | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| IQR | = | interquartile range |

| NAFLD | = | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

Acknowledgement

The data used for the research were from THL (obtained from THL Biobank). We thank all study participants for their generous participation in the FINRISK 1997 and Health 2000 studies.

Disclosure statement

VS has received honoraria for consulting from Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. He also has ongoing research collaboration with Bayer (all unrelated with the present study). SB reports grants and personal fees from Abbott Laboratories, Bayer, Siemens, and Thermo Fisher Scientific, grants from Singulex, and personal fees from Astra Zeneca, Amgen, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Roche, outside the submitted work.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Elangovan H, Chahal S, Gunton JE. Vitamin D in liver disease: current evidence and potential directions. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863(4):907–916.

- Anty R, Canivet CM, Patouraux S, et al. Severe vitamin D deficiency may be an additional cofactor for the occurrence of alcoholic steatohepatitis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39(6):1027–1033.

- Savic Z, Vracaric V, Milic N, et al. Vitamin D supplementation in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a prospective study. Minerva Med. 2018;109:352–357.

- Kubesch A, Quenstedt L, Saleh M, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with hepatic decompensation and inflammation in patients with liver cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207162.

- Borodulin K, Tolonen H, Jousilahti P, et al. Cohort profile: the national FINRISK study. Int J Epidemiol. 2018;47(3):696–696.

- Heistaro S. Methodology report: health 2000 Survey. Helsinki, Finland: Publications of the National Public Health Institute; 2008.

- Aberg F, Helenius-Hietala J, Puukka P, et al. Binge drinking and the risk of liver events: a population-based cohort study. Liver Int. 2017;37(9):1373–1381.

- Pukkala E. Biobanks and registers in epidemiologic research on cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;675:127–164.

- Sund R. Quality of the Finnish hospital discharge register: a systematic review. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(6):505–515.

- Vogt S, Wahl S, Kettunen J, et al. Characterization of the metabolic profile associated with serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D: a cross-sectional analysis in population-based data. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(5):1469–1481.

- Jaaskelainen T, Knekt P, Marniemi J, et al. Vitamin D status is associated with sociodemographic factors, lifestyle and metabolic health. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52:513–525.

- Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):53–58.

- Skaaby T, Husemoen LL, Borglykke A, et al. Vitamin D status, liver enzymes, and incident liver disease and mortality: a general population study. Endocrine. 2014;47(1):213–220.

- Wu DB, Wang ML, Chen EQ, et al. New insights into the role of vitamin D in hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12(3):287–294.

- Naderpoor N, Mousa A, Fernanda Gomez Arango L, et al. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on faecal microbiota: a randomised clinical trial. Nutrients. 2019;11(12):2888.

- Mansouri L, Lundwall K, Moshfegh A, et al. Vitamin D receptor activation reduces inflammatory cytokines and plasma MicroRNAs in moderate chronic kidney disease - a randomized trial. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):161–017.

- Salekzamani S, Mehralizadeh H, Ghezel A, et al. Effect of high-dose vitamin D supplementation on cardiometabolic risk factors in subjects with metabolic syndrome: a randomized controlled double-blind clinical trial. J Endocrinol Invest. 2016;39(11):1303–1313.

- Hariri M, Zohdi S. Effect of vitamin D on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10(14):14–21.

- Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Bjelakovic M, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for chronic liver diseases in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(11):CD011564.