Abstract

Background

Prospectively and systematically collected real-world data on the effectiveness of ustekinumab (anti-interleukin-12/23) for treating Crohn’s disease (CD) are still limited.

Aim

To assess the short-term real-world effectiveness of ustekinumab in Swedish patients with active CD.

Methods

Prospective multicentre study of adult CD patients initiating ustekinumab according to recommended doses at 20 hospitals, between January 2017 and November 2018. Data were collected through an electronic case report form (eCRF) linked to the Swedish Inflammatory Bowel Disease Registry (SWIBREG). The primary outcomes were clinical response (≥3-point-decrease of Harvey–Bradshaw index (HBI)) and remission (HBI ≤4 points) at week 16. Secondary outcomes included C-reactive protein (CRP) and haemoglobin (Hb) at baseline compared to week 16.

Results

Of 114 included patients, 107 (94%) had failed ≥ 1 and 58 (51%) ≥ 2 biological agents (anti-tumour necrosis factor [aTNF] agents or vedolizumab). The 16-week ustekinumab retention rate was 105 (92%). Data on HBI at baseline were available for 96 patients. At week 16, response or remission was achieved in 38/96 (40%) patients (25/96 (26%) achieving clinical remission and 23/96 (24%) showing a clinical response). The median CRP concentration (N = 65) decreased from 6 to 4 mg/l (p = .006). No significant changes in Hb were observed. No incident malignancies or infections, requiring antibiotic treatment, were reported.

Conclusions

In this nation-wide prospective real-world study of adult patients with CD, ustekinumab was associated with clinical effectiveness when administered according to clinical practice and seemed to represent a safe treatment option.

Introduction

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic relapsing inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract [Citation1]. The disease is becoming increasingly common worldwide, with more than 20,000 affected individuals in Sweden only [Citation2]. Diagnosis is often at a young age, and the disease course is associated with loss of work productivity, increased morbidity and mortality [Citation2–5]. To minimise disease progression, treatment algorithms of CD aim to induce and maintain remission [Citation6]. Historically, immunomodulators were often used as first-line treatment [Citation7,Citation8]. When this option failed, anti-tumour necrosis factor (aTNF) agents and surgery remained as alternative treatment options. However, the observation that around 30% of aTNF treated patients are primary non-responders and approximately 40% of responders experience secondary failure with loss of response or intolerance [Citation9–13] has triggered a search for new treatment options. Additional biological agents with novel mechanisms of actions have recently been introduced and among these ustekinumab represents an increasingly used option.

Ustekinumab was approved by the European Medicines Agency and by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States in 2016. It is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with moderately to severely active CD who have had an inadequate response with, lost response to or were intolerant to either conventional therapy or aTNF or had medical contraindications to such therapies. The efficacy of ustekinumab to induce and maintain disease remission in patients with moderate to severe CD has been demonstrated in two randomised clinical induction trials (UNITI-1 and UNITI-2) [Citation14], and a maintenance trial (IM-UNITI) [Citation15]. Even though the pivotal trials included both patients with previous aTNF failure and aTNF naïve patients [Citation16–19], they do not accurately reflect real-world clinical practice. In real-world clinical settings, patients with CD are more heterogeneous. Furthermore, many patients seen in clinical practice would not be eligible for inclusion in a clinical trial [Citation18]. To date, there are several observational studies presenting real-world data on the clinical effectiveness of ustekinumab [Citation19–28]. In several of these studies, ustekinumab was administered subcutaneously and/or with various dosing patterns [Citation23–26,Citation29,Citation30], since they were based on compassionate use before the drug was approved for the treatment of CD. Previous studies are also limited by retrospective designs and, to our knowledge, only one study is entirely based on prospectively collected data [Citation22]. Whether the results from these studies can be applied to ustekinumab-treated patients in general remains unknown since data from nation-wide real-world cohorts, with a balanced representation of regional hospitals and university hospitals, are lacking.

The aim of this study was to examine the short-term clinical effectiveness of ustekinumab in CD. We did so through a nation-wide observational study, where real-world data were prospectively and systematically collected. We assessed outcomes 16 weeks after initiation of treatment.

Methods

Study design and endpoints

This was a Swedish nation-wide multicentre prospective non-interventional observational study of patients initiated on ustekinumab according to the standard practice of care between 23 January 2017 and 22 November 2018. Treating physicians independently initiated ustekinumab treatment and assessed clinical and biochemical response during follow-up according to national treatment guidelines [Citation27].

Study participants

We included patients with a confirmed international classification of disease (ICD) diagnosis of CD (ICD-10: K50 all sub-classifications) with active CD, as defined by the treating physician, based on clinical activity, inflammatory markers, endoscopic findings or response to concomitant medication (including corticosteroids). Included patients were (i) naïve to, (ii) had an inadequate response to, (iii) lost response to, (iv) were intolerant to either conventional therapy or aTNF or (v) had medical contraindications to such therapies. All patients began treatment with ustekinumab on or after their 18th birthday.

Patients with previous exposure to ustekinumab or concurrent participation in other clinical studies were excluded. For the included patients from 20 Swedish hospitals, baseline and clinical follow-up data were reported through a standardised study-specific electronic case report form (eCRF) directly linked to the Swedish Inflammatory Bowel Disease Registry (SWIBREG) [Citation28]. SWIBREG is a nation-wide registry for IBD founded in 2005, covering around 80% of the Swedish IBD population (n = 52,003 patients, August 2020) [Citation31]. The registry contains extensive quality data on CD phenotype, treatment (including biologics), surgery and quality of life. To be included in the study, a patient had to be initiated on ustekinumab within the last 2 weeks before inclusion or started treatment <12 months ago if detailed information on the treatment was documented in SWIBREG within 2 weeks of treatment initiation.

The primary objective was to determine the short-time clinical effectiveness of ustekinumab as the proportion of patients with clinical response and remission assessed as a change in Harvey–Bradshaw index (HBI) [Citation32] comparing scores at baseline, i.e. at the initiation of ustekinumab treatment, and at week 16. Clinical response was defined as a reduction of HBI score ≥3 points. Clinical remission was defined as HBI score ≤4 points. Secondary objectives included the impact of ustekinumab on inflammatory biomarkers, C-reactive protein (CRP), haemoglobin (Hb) and faecal (f)-calprotectin, comparing levels at baseline and at week 16.

Ustekinumab

All induction doses of ustekinumab were administered intravenously according to the EU summary of product Characteristics recommendation of 6 mg/kg in steps of 130 mg. A 90 mg subcutaneous injection was administered 8 weeks after the intravenous dose and the next 90 mg subcutaneous dose either 8 or 12 weeks after first subcutaneous injection.

Data collection

Baseline data, including demographics and clinical characteristics such as year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, history of previous CD related bowel surgery, relevant comorbidities and extraintestinal manifestations, disease location and behaviour according to the Montreal Classification [Citation33] and clinically relevant medication for CD (including biologics and reasons for discontinuation) were collected from SWIBREG. Data on clinical and biochemical disease activity were recorded at baseline (±2 weeks) and follow-up visit at week 16 (±2 weeks). We also documented if and why patients discontinued ustekinumab treatment during follow-up. During the scheduled visits, we recorded adverse events of special interest for ustekinumab, such as malignancy and infections. Any such adverse events were promptly reported by the investigating physician directly to Janssen Cilag AB according to the obligations of pharmacovigilance of drug manufacturers and to the Swedish Medical Products Agency.

Statistical analysis

We reported descriptive findings as median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, biochemical and clinical outcomes and as proportions for categorical variables. Calculations of clinical response and remission rates at week 16 were restricted to patients with data on HBI recorded at baseline (±2 weeks). Comparisons of clinical disease activity and inflammatory markers between baseline and week 16 were restricted to patients who had data recorded at both time points. Changes in median HBI, CRP, Hb and f-calprotectin were analysed by the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and tests with p<.05 were considered statistically significant. Data management and statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (MS Office 2016), SAS version 9 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA software version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical considerations

All patients included in PROSE signed an informed consent authorising access to and the use of clinical data collected in this study. This project was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping, Sweden (2017-290-31).

Results

Patient characteristics

We included 114 patients representing 20 different hospitals (Appendix 1) with a geographical coverage of almost all of Sweden (). Patient characteristics at baseline are presented in . Patients were predominately male (n = 60, 53%), nearly all (n = 107, 94%) had previously failed at least one biological drug and approximately one third (n = 37, 32%) had a history of previous CD-related bowel surgery. At baseline, 47 (41%) patients had concomitant treatment with immunomodulators and/or corticosteroids, and 69 (72%) patients had an HBI ≥5 with a median HBI of 6 (IQR 4–11) ().

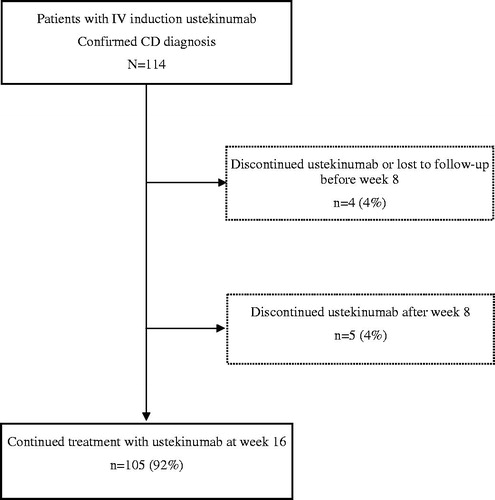

Figure 1. Flowchart of ustekinumab treatment in the PROSE study population. A total of 114 patients with confirmed Crohn’s disease (CD) diagnosis received intravenous ustekinumab induction treatment at week 0. A total of 110 (96%) patients received a subcutaneous injection at week 8. Treatment retention at week 16 was 105 (92%) patients. Of these, four (4%) patients discontinued or were lost to follow-up (lack of response, n = 1; pregnancy, n = 1; lost to follow-up, n = 2) before week 8 and 5 (4%) patients (lack of response, n = 5) between week 8 and 16.

Table 1. Baseline patient characteristics and phenotype according to the Montreal classification.

Dosing and treatment persistence

The 16-week drug retention rate was 105/114 (92%) (). Reasons for termination of ustekinumab before week 16 were lack of response (n = 6), pregnancy (n = 1) and lost to follow-up (n = 2). Of 114 patients receiving an intravenous induction dose, 110 received at least one 90 mg subcutaneous dose of ustekinumab 8 weeks after the induction dose.

Clinical effectiveness

Clinical remission and response

We calculated clinical response and remission based on HBI at week 16 compared to baseline. Data on HBI were available for 96 patients at baseline, and 89 (93%) of these patients remained on ustekinumab treatment after 16 weeks. At week 16, 23/96 (24%) patients had a clinical response (HBI decrease ≥3), 25/96 (26%) were in clinical remission (HBI ≤4), and 38/96 (40%) achieved either clinical response or remission. However, data on HBI at week 16 were missing for 25 patients with ongoing ustekinumab treatment.

Of patients with HBI ≥5 at baseline (n = 50), response at week 16 was achieved in 23 (46%), remission in 13 (26%) and 26 (52%) achieved either clinical response or remission (). Overall, the median HBI was 6 (IQR 4–11) at baseline and 5 (IQR 4–7) at week 16. Among patients with data on HBI at both time points, the median HBI decreased by 1 (IQR −3 to −1, p = .003) from baseline to week 16 ().

Table 2. Harvey–Bradshaw index, clinical remission, response and inflammatory marker levels at baseline and at week 16.

Table 3. Clinical and laboratory parameters at baseline and at week 16 among ustekinumab treated patients with Crohn’s disease.

Biochemical effectiveness

In total, 65 patients had data on CRP at baseline and week 16, and 18 patients had the corresponding information on f-calprotectin (). The median CRP concentration decreased from 6 mg/l at baseline to 4 mg/l at week 16 (p = .006). The median f-calprotectin level decreased from 266 to 189 µg/g (p = .02). No significant changes in Hb were observed.

Adverse events

No incident malignancies or infections requiring antibiotic treatment were recorded during follow-up.

Discussion

In this nation-wide Swedish prospective observational multicentre study, we report patient characteristics, clinical and inflammatory markers of response and remission rates in a cohort of patients with CD initiated on ustekinumab according to clinical practice. We included a total of 114 patients. Of these, 105 were still on treatment with ustekinumab at week 16. Data were collected and reported by treating physicians through an eCRF linked to the Swedish IBD registry SWIBREG. The results represent the real-world clinical practice of ustekinumab treatment in patients with active CD.

We observed clinical remission at week 16 in 26% (n = 25/96) patients, and response was achieved in 24% (n = 23/96) and clinical benefit, defined as response or remission at week 16, in 40% (n = 38/96). These results were supported by a statistically significant decrease in median HBI, CRP and f-calprotectin at week 16 compared to baseline but no significant change in levels of Hb ().

These findings can be compared with those of the registration trials UNITI-1 and 2 where response rates of 34 and 56% were reported at 6 weeks [Citation14]. However, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) provide data only on well-defined and selected groups of patients treated under strict protocols. In this study, patients were included independently by physicians and treated according to clinical practice. In such a real-world clinical setting, patient populations are more heterogeneous, and treatment patterns vary depending on patient characteristics and clinical decisions by treating physicians. Furthermore, in UNITI-1 and 2 patients without previous treatment with aTNF and primary or secondary non-response to such treatment were included. In the maintenance study IM-UNITI, 44% of patients had previous aTNF treatment [Citation15]. In our study, 94% (n = 107/114) had failed at least one biological drug (aTNF or vedolizumab). Some 78% (n = 83/107) of those terminated last biological treatment due to lack of response. This is similar to recent real-world observational studies [Citation19–22] and confirms the short-term effectiveness of ustekinumab even when used outside the context of tertiary referral centres, i.e. in a variety of care contexts, including both regional and university hospitals.

One-quarter of the patients in this study recorded a clinical response, and a similar proportion was in clinical remission at week 16. A total of nine patients discontinued or were lost to follow-up. Of these, six terminated ustekinumab treatment due to lack of response. Previous observational real-world single and multicentre studies with comparable patient cohorts and follow-up times have shown short-term response rates between 16 and 84% [Citation19–26,Citation29,Citation34,Citation35]. However, the dosing regimens have varied, not always reflecting the current EU Summary of Product Characteristics for ustekinumab with intravenous induction followed by subcutaneous injections. This may play an important role in the largely varying rates in previous studies along with the use of different assessment scores for response and remission, such as Crohn’s Disease (CD) Activity Index and HBI. When restricting the comparison to real-world studies adhering to the summary of product characteristics, and using the same definitions for response and remission as in our study, short-term (12–16 weeks follow-up) response rates of 16–52% and remission rates of 31–58% have been observed [Citation19–22]. In our study, we show comparable response and remission rates of 24 and 26%, respectively.

Our study has several strengths, such as the nation-wide prospective observational design, which enabled us to capture the real-world clinical effectiveness of ustekinumab. A nation-wide inclusion of patients from 20 Swedish regional and university hospitals based on the individual physician’s independent decision to initiate the patient on ustekinumab according to clinical practice reflects a real-world setting. To our knowledge, no previous prospective studies of ustekinumab have included IBD patients representing both different hospital types and different clinical settings. The quality of the collected data was strengthened by the standardisation of data collection through an eCRF. Furthermore, in contrast to some previous studies where heterogeneous dosing protocols have been applied [Citation23,Citation25,Citation26,Citation30], induction and maintenance dosing adhered to the label and national guidelines in our study. In this study, all patients received one intravenous induction dose followed by subcutaneous doses.

Among the limitations of this study are the inherent limitations of multicentre observational studies, including a lack of compulsory assessment of HBI, inflammatory markers and endoscopic activity. To determine the clinical remission and response rate at week 16, we applied an intention-to-treat methodology and included all patients with data on HBI at baseline, including those who had discontinued treatment (n = 7) before week 16. The number of patients with reported HBI score within the set time-frame was lower than expected, rendering lower statistical power than planned. However, the calculated clinical response and remission were both statistically significant and supported by a reduction in the concentration of CRP. Data on f-calprotectin were available for only 16% of the patients at both time points, making it difficult to assess the overall inflammatory response based solely on f-calprotectin. The low proportion of patients with data on f-calprotectin levels at both baseline and week 16 may in part be explained by the tight time-windows for recording this information. The lack of f-calprotectin assay standardisation further complicates the interpretation of this inflammatory marker. Therefore, the results of f-calprotectin should be interpreted with caution. The nine patients who discontinued or were lost-to follow-up before week 16 did not differ significantly at baseline from those included in the week 16-analyses (data not shown).

In conclusion, ustekinumab achieved both clinical remission and response, as well as biochemical response in patients with active CD who were almost exclusively aTNF refractory. Ustekinumab proved safe in this real-world setting of CD patients. Our results give further support to previous studies showing evidence for ustekinumab as a valuable, efficient and safe treatment of CD.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: JFL, JH, FH. Acquisition of data: AF, JFL, JH, HS, CS, AW, DA. Statistical analyses: AF, MC. First draft of the manuscript: AF, JFL, JH. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: JH, JFL, AF, OO, PM, HS, CS, AW, DA, FH. Funding: FH. Study supervision: JFL.

| Abbreviations | ||

| CD | = | Crohn’s disease |

| HBI | = | Harvey–Bradshaw Index |

| IBD | = | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| ICD | = | International classification of disease |

| SWIBREG | = | Swedish Inflammatory Bowel Disease Registry |

| aTNF | = | Anti-tumour necrosis factor |

Acknowledgements

Ida Gustavsson, Kristin Klarström-Engström and Mariam Lashkariani.

Disclosure statement

P Myrelid served as speaker and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Ferring, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, Baxter and Tillotts Pharma.

H Strid served as speaker and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Ferring, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, Gilead and Tillotts Pharma.

D Andersson served as speaker and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Janssen and Takeda. O.

F Hjelm is an employee of Janssen Cilag AB.

Olén has been PI on projects at Karolinska Institutet, partly financed by investigator-initiated grants from Janssen and Ferring, and Karolinska Institutet has received fees for lectures and participation on advisory boards from Janssen, Ferring, Takeda, and Pfizer.

O Olén also reports a grant from Pfizer in the context of a national safety monitoring programme.

J Halfvarson served as speaker and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Celgene, Celltrion, Dr. Falk Pharma and the Falk Foundation, Ferring, Hospira, Janssen, MEDA, Medivir, MSD, Olink Proteomics, Pfizer, Prometheus Laboratories, Sandoz/Novartis, Shire, Takeda, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tillotts Pharma, Vifor Pharma, UCB and received grant support from Janssen, MSD, and Takeda. No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1590–1605.

- Olen O, Erichsen R, Sachs MC, et al. Colorectal cancer in Crohn’s disease: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(5):475–484.

- Olen O, Askling J, Sachs MC, et al. Mortality in adult-onset and elderly-onset IBD: a nationwide register-based cohort study 1964–2014. Gut. 2020;69(3):453–461.

- Everhov Å, Sachs MC, Ludvigsson JF, et al. Work loss in relation to pharmacological and surgical treatment for Crohn’s disease: a population-based cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2020;12:273–285.

- Khalili H, Everhov Å, Halfvarson J, et al. Healthcare use, work loss and total costs in incident and prevalent Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: results from a nationwide study in Sweden. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52(4):655–668.

- Gomollon F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(1):3–25.

- Everhov AH, Halfvarson J, Myrelid P, et al. Incidence and treatment of patients diagnosed with inflammatory bowel diseases at 60 years or older in Sweden. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(3):518–528.

- Zhulina Y, Udumyan R, Henriksson I, et al. Temporal trends in non- stricturing and non-penetrating behaviour at diagnosis of Crohn’s disease in Örebro, Sweden: a population-based retrospective study. J Crohn Colitis. 2014;8(12):1653–1660.

- Ben-Horin S, Kopylov U, Chowers Y. Optimizing anti-TNF treatments in inflammatory bowel disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(1):24–30.

- Allez M, Karmiris K, Louis E, et al. Report of the ECCO pathogenesis workshop on anti-TNF therapy failures in inflammatory bowel diseases: definitions, frequency and pharmacological aspects. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4(4):355–366.

- Papamichael K, Gils A, Rutgeerts P, et al. Role for therapeutic drug monitoring during induction therapy with TNF antagonists in IBD: evolution in the definition and management of primary nonresponse. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(1):182–197.

- Ding NS, Hart A, De Cruz P. Systematic review: predicting and optimising response to anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease – algorithm for practical management. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43(1):30–51.

- Gisbert JP, Panes J. Loss of response and requirement of infliximab dose intensification in Crohn’s disease: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):760–767.

- Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(20):1946–1960.

- Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Gasink C, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of ustekinumab for Crohn's disease through the second year of therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48(1):65–77.

- Khanna R, Preiss JC, MacDonald JK, et al. Anti-IL-12/23p40 antibodies for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(5):CD007572.

- Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, et al. Ustekinumab Crohn’s disease study G: a randomised trial of Ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(4):1130–1141.

- Ha C, Ullman TA, Siegel CA, et al. Patients enrolled in randomized controlled trials do not represent the inflammatory bowel disease patient population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(9):1002–1007.

- Eberl A, Hallinen T, Af BC, et al. Ustekinumab for Crohn’s disease: a nationwide real-life cohort study from Finland (FINUSTE). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:718–725.

- Liefferinckx C, Verstockt B, Gils A, et al. Long-term clinical effectiveness of ustekinumab in patients with Crohn’s disease who failed biologic therapies: a national cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13(11):1401–1409.

- Iborra M, Beltran B, Fernandez-Clotet A, et al. Real-world short-term effectiveness of ustekinumab in 305 patients with Crohn’s disease: results from the ENEIDA registry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50(3):278–288.

- Biemans VBC, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, van der Woude CJ, et al. Ustekinumab for Crohn’s disease: results of the ICC registry, a nationwide prospective observational cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(1):33–45.

- Kopylov U, Afif W, Cohen A, et al. Subcutaneous ustekinumab for the treatment of anti-TNF resistant Crohn’s disease-the McGill experience. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(11):1516–1522.

- Khorrami S, Ginard D, Marin-Jimenez I, et al. Ustekinumab for the treatment of refractory Crohn’s disease: the Spanish experience in a large multicentre open-label cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(7):1662–1669.

- Battat R, Kopylov U, Bessissow T, et al. Association between ustekinumab trough concentrations and clinical, biomarker, and endoscopic outcomes in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(9):1427–1434.

- Wils P, Bouhnik Y, Michetti P, et al. Subcutaneous ustekinumab provides clinical benefit for two-thirds of patients with Crohn’s disease refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor agents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(2):242–250.

- Swedish Medical Products Agency: Läkemedelsbehandling vid inflammatorisk tarmsjukdom – ny rekommendation. Information från Läkemedelsverket. 2:2012.

- Ludvigsson JF, Andersson M, Bengtsson J, et al. Swedish inflammatory bowel disease register (SWIBREG) – a nationwide quality register. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(9):1089–1101.

- Ma C, Fedorak RN, Kaplan GG, et al. Long-term maintenance of clinical, endoscopic, and radiographic response to ustekinumab in moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease: real-world experience from a multicenter cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(5):833–839.

- Ma C, Fedorak RN, Kaplan GG, et al. Clinical, endoscopic and radiographic outcomes with ustekinumab in medically-refractory Crohn;’s disease: real world experience from a multicentre cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(9):1232–1243.

- SWIBREG yearly report 2019 (SWIBREG Årsrapport för 2019). 2020.

- Harvey RF, Bradshaw JM. A simple index of Crohn’s-disease activity. Lancet. 1980;1(8167):514.

- Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, et al. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55(6):749–753.

- Macaluso FS, Maida M, Ventimiglia M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of Ustekinumab for the treatment of Crohn's disease in real-life experiences: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2020; 20(2):193–203.

- Saman S, Goetz M, Wendler J, et al. Ustekinumab is effective in biological refractory Crohn’s disease patients-regardless of approval study selection criteria. Intest Res. 2019;17(3):340–348.

Appendix 1

List of Swedish hospitals including patients in the PROSE study

Blekinge Hospital, Karlskrona

Danderyd University Hospital, Stockholm

Kalmar County Hospital, Kalmar

Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm

Linköping University Hospital, Linköping

NÄL Hospital Trollhättan, Trollhättan

Ryhov County Hospital, Jönköping

Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg

Skaraborgs Hospital Lidköping, Lidköping

Skåne University Hospital, Lund

Skåne University Hospital, Malmö

Stockholm Gastro Center, Stockholm

Capio St Göran Hospital, Stockholm

Sunderby Hospital, Luleå

Sundsvall Regional Hospital, Sundsvall

Södra Älvsborg Hospital, Borås

University Hospital of Umeå, Umeå

Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala

Västerås Central Hospital, Västerås

Örebro University Hospital, Örebro