Abstract

Introduction

To improve oncological outcome in right colon cancer surgery, an extended mesenterectomy (D3) is under evaluation. In this procedure, all tissue anterior and posterior to the superior mesenteric vessels from the middle colic to ileocolic artery origin is removed, causing injury to the superior mesenteric nerve plexus. The aim was to study the effects of this injury on bowel dynamics and quality of life (QoL).

Methods

Patients undergoing right colectomy with conventional D2- and extended D3-mesenterectomy were asked to record stool number and consistency for 60 d after surgery and complete questionnaires regarding QoL and bowel function (BF) before and after recovery from surgery. We compared early postoperative stool dynamics and long-term QoL in the groups and presented graphs depicting the temporal profile of stool numbers and consistency.

Results

Thirty-three patients operated with a D3-resection and 12 patients with a D2-resection participated. The results revealed significantly higher stool numbers in the D3-group until day 26, with significantly more loose-watery stools until day 40. The most pronounced difference was found on day 9 (Mean difference in the total number of stools: 2.25 stools/day, p=.004. Mean difference in loose-watery stools/day: 2.81 p<.001). About 25% in the D2- and 69.7% in the D3-group reported having more than three stools/day in the early postoperative phase. There were no differences in long-term QoL and BF between the groups except in stool consistency (p=.039).

Discussion/conclusions

Denervation following extended D3-mesenterectomy leads to transitory reduced consistency and increased frequency. It does not affect long-term QoL or BF.

Introduction

In surgery for colorectal cancer, the right colon represents a particular challenge. The right colon shares vessels (superior mesenteric artery [SMA] and vein [SMV]), lymphatics and extrinsic nerves (superior mesenteric plexus [SMP]) with the small bowel [Citation1]. The traditional D2-mesenterectomy includes peripheral branches to the right colon with the surrounding lymph nodes [Citation2]. The extended D3-mesenterectomy also removes the tissue with the lymph nodes around the superior mesenteric vessels [Citation3]. Consequently, the SMP in the same area is removed. Since the small bowel continuity is preserved, the extrinsic nerves are affected, not the intrinsic nerves (i.e., enteric nervous system [ENS]).

Two studies concerning bowel function (BF) and quality of life (QoL) after extended D3-mesenterectomy report excellent long-term results [Citation4,Citation5]. A study with wireless motility capsules (WMC) revealed a significantly reduced small bowel transit time 3 weeks after surgery [Citation6]. The clinical correlation to this early postoperative finding is not studied.

This study’s main aim was to compare the immediate postoperative changes in BF after right colectomy with and without extended D3-mesenterectomy. A secondary aim was to compare the BF and QoL in the groups after recovery from surgery.

Material and methods

Patients

Inclusion criteria

Patients with right colon cancer scheduled for right colectomy were invited to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria for participation were: good general condition, regular BF before surgery (not taking cancer-related symptoms into account) and a normal activity level. Patients who had undergone previous bowel resections and patients with pre-existing conditions known to affect the stool pattern (IBD, IBS, Celiac disease, anal incontinence, etc.) were not included in the study. The participation was voluntary.

Exclusion criteria

Extended bowel resection at surgery, postoperative complications affecting the postoperative BF.

The experimental group (D3)

Consecutive patients included in the multicenter trial ‘Safe Radical D3-Right Hemicolectomy for Cancer through Preoperative Biphasic Multi-Detector Computed Tomography’. All patients who were 75 years old or younger were offered the new procedure.

The control group (D2)

Consecutive patients operated with right colectomy with traditional D2-mesenterectomy and fulfilling the inclusion as mentioned above. Since patients 75 years or younger were offered D3 lymphadenectomy, this group of patients is older than 75 years except for those who did not participate in the trial mentioned above.

Surgical procedure

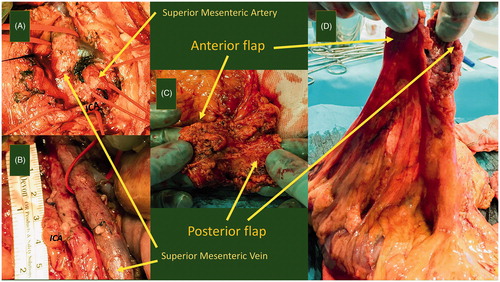

The surgical procedure differs in the central lymphadenectomy and has previously been described [Citation3,Citation7,Citation8]. The plane for the central dissection is between the superior mesenteric vessels and their sheaths. All tissue anterior and posterior to the superior mesenteric vessels from 5 mm proximal to the middle colic artery origin to 10 mm distal to the ileocolic artery origin is removed. The medial border follows the left border of SMA ().

Figure 1. The D3-dissection. The figure depicts the radicality of the central dissection. (A) After opening the left side of the mesentery along a line following the medial border of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), the surgeon opens the artery's vascular sheath. Dissecting toward the right in the well-defined plane between the vessels and their sheaths, the surgeon lifts the anterior flap. Here we see that the ileocolic artery (ICA) crosses the superior mesenteric vein in the front. (B) Now, the ICA and the ileocolic vein are ligated and divided at their origins. SMV is carefully pulled to the left as the posterior flap is dissected out from behind the SMA, still in the plane between the artery and the vascular sheath. The dorsal delimitation of this flap is Toldt’s fascia. (C) Pictures the specimen with the vascular groove and the inner surface of the two flaps. (D) Depicts the mesentery, the two flaps, and the vascular groove from another angle.

Perioperative preparation/medication

Bowel preparation was not given. All patients had antibiotic prophylaxis (metronidazole/doxycycline). No laxatives were given after surgery.

Data collection

Diary

The patients were asked to mark all their stools after surgery (preferably 2 months or at least until stabilization) in a diary, choosing one out of three predefined characters depending on the stools’ consistency.

BF and QoL

The patients completed BF and QoL questionnaires twice: preoperative (regarding the status before the onset of any cancer-related symptoms, at least 6 months prior to surgery) and after recovery (1 year after surgery and at least 6 months after finishing adjuvant chemotherapy).

The instruments

Diarrhea assessment scale (DAS)

A validated tool for determining four aspects of diarrhea (frequency, consistency, urgency and abdominal discomfort): 0–12, 12 is worst [Citation9].

Gastrointestinal quality of life index (GIQLI; 0–144) with sub-scores

The following subscales were used: physical role (0–44), colon function (0–32), emotional role (0–32), upper GI function (0–32) and meteorism (0–12) [Citation10].

36-Item short-form health survey (SF-36)

From 36 questions, the following scores were calculated: Physical functioning (0–100), role-physical (0–100), bodily pain (0–100), general health (0–100), vitality (0–100), social functioning (0–100), role-emotional (0–100) and mental health (0–100) [Citation11].

Stool frequency

No separate stool frequency question was included in the interviews before surgery and after recovery. The DAS stool frequency score was used to determine stool frequency. Since the score was truncated at the lower and upper end, this was under the assumption that few patients had stools less than once or more than four times daily.

Degree of disturbance

Additional question: ‘Does your bowel function bother you’? (no: 0, a little: 1, much: 2, very much: 3)

Data analysis

Missing diary data

We instructed the patients to record their stools for 60 d after surgery or at least until stabilization. When a patient stopped recording the stools or started adjuvant chemotherapy earlier than 60 d after surgery, the remaining days were left out.

Missing questionnaire items

In Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI), single missing items were replaced by person-mean imputation. Questionnaires with multiple missing items were excluded. In SF-36, the missing items were dealt with according to the scoring instructions. In DAS, missing items led to the exclusion of the score.

Postoperative stool pattern and dynamics

Graphs representing the temporal profile of stool number and consistency were used to visualize and compare the early postoperative BF. An independent samples t-test (SPSS) was performed to compare the daily stool frequency between the groups.

QoL and BF after recovery

Postoperative QoL- and BF-scores in the groups were compared with linear regression analysis, controlling for preoperative scores.

Ethics committee approval

The multicenter trial for right colectomy with extended D3-mesenterectomy is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov on 9 May 2011 (NCT01351714) and has ethical committee approval from the regional ethical committee (REK Sør-Øst No. 2010/3354). Comparison of BF after D3-and D2-right colectomy was also approved (REK Sør-Øst No. 2015/403-3). Written informed consent was acquired from the patients before inclusion, both for the multicenter trial and the present BF/QoL-study.

Results

Patients

Forty-one (18 men) were included in the experimental group (D3) and 18 patients (8 men) in the control group (D2).

Exclusion

D3: Anastomotic leakage: 2 men. Five patients (2 men) did not return the diary. One woman stopped recording the stools after having a bleeding ulcer.

D2: Anastomotic leakage: 1 man. Two men underwent reoperation due to postoperative bleeding and bowel obstruction. Three women did not return the diary. When dropouts are in concern, overall rate was 13.6% (D2: 16.7%; D3: 12.2%).

Patients after exclusion

Thirty-three D3-patients (14 men) with a median age of 70 years and 12 D2-patients (5 men) with a median age of 77.3 years completed the study. The groups were comparable for gender (p=.964, Chi-square test of independence). There was a small, but statistically significant difference of 6.77 years between the groups (Mean age: D2 = 73.50 ± 8.91 years, D3 = 66.73 ± 8.57 years, independent samples T-test: 0.03).

Histopathology

The mean length of the resected colon was comparable (D2 = 23.89 cm, D3 = 26.16 cm (formalin-fixed specimens). The difference between the resected ileum mean lengths is: 5.09 cm (Mean length: D2 = 6.94 ± 4.35 cm, D3 = 12.03 ± 4.07 cm, independent samples T-test: 0.01).

Diaries

All patients recorded stools for at least 3 weeks (the period with the most significant postoperative changes). Twenty-five out of 33 D3-patients completed the diary for the whole period (60 d). Three D3-patients stopped due to a stabilization of the stool frequency. Five D3-patients stopped due to the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy. Eight out of 12 D2-patients completed the diary for the whole period. Three patients stopped due to a stabilization of the stool frequency. One patient ended the recording due to the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy.

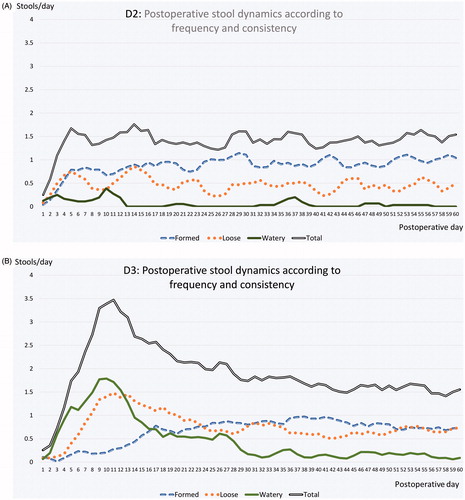

Diary data

The median time from surgery to the first bowel movement was equal in the two groups: 3 d (1–8) for the D3-group and 3 d (2–5) for the D2-group (p=.653, Whitney–Mann). In the first postoperative days, the diaries revealed significantly higher stool frequencies in the D3-group than in the D2 group. The most pronounced difference was found on day 9, with 2.25 more stools per day (mean) in D3-group than in the D2-group (p =.004, CI = 0.740–3.760). At that time, most of the stools in the D3-group were loose or watery. The mean difference in loose or watery stools per day between the groups on day 9 was 2.81 (p<.001, CI = 1.635–3.986). In the early postoperative period, the D2-group presented a regular stool pattern with mainly formed stools (), whereas the D3-group had frequent stools with watery and loose consistency (). In the D2-group, 75% of the patients never had more than three stools per day. 16.7% had a maximal stool frequency between four and six stools per day, and only one patient (8.3%) reported having more than seven bowel movements on 1 d. In the D3-group, 30.3% of the patients never had more than three stools per day in the postoperative period. About 27.3% had a maximal stool frequency between four and six stools per day, and 42.4% of the patients reported having more than seven bowel movements on 1 d. The difference between the groups continued over the next weeks with significantly higher total stool frequency in the D3 group up to day 26 (p< .05) and significantly more loose or watery stools in the D3 group up to day 40 (<0.05). The differences slowly diminished until the frequency and consistency were approximately the same in both groups after 60 d.

Figure 2. (A) The graphs depict the stool trends during the first 60 d after right colectomy with a traditional D2-mesenterectomy using a 3-points moving average. The graphs represent the total number of stools per day, as well as the number of formed, loose and watery stools per day. (B) The graphs depict the stool trends during the first 60 d after right colectomy with extended D3-mesenterectomy using a 3-points moving average. The graphs represent the total number of stools per day, as well as the number of formed, loose, and watery stools per day.

QoL and BF after recovery

The postoperative QoL- and BF-questionnaires were completed17 months (median; 10–25) after the operation in the D2-group and 18 months (median; 10–24) in the D3-group. The mean time from chemotherapy to completion was 11 months in the D2-group (one patient) and 9.3 months in the D3-group. No forms were completed earlier than 6 months after ended chemotherapy. When controlled for the preoperative scores, we found no significant difference between the groups in SF-36 scores, GIQLI or GIQLI subscores. We found no significant difference in the total DAS-score, even though the consistency score (DAS-item) was 0.48 higher in the D3 group than in the D2 group (p=.036). There was no significant difference in stool frequency. For a complete overview, see .

Table 1. Postoperative scores (after recovery) in the groups (D2/D3), differences between the groups without and with control for preoperative scores

Discussion/conclusion

Whereas the length of the postoperative ileus and the hospital stay after bowel surgery have been well documented [Citation12], there are no publications concerning stool frequency and consistency during the first weeks after right colectomy. This is the first diary-based study to describe BF dynamics throughout the early postoperative period after right colectomy, and the first study to compare the early postoperative BF in two groups operated with right colectomy with and without extrinsic denervation. The study reveals a significantly higher stool frequency and reduced stool consistency in the early postoperative phase in the group operated with extended D3-mesenterectomy. Since both procedures are identical, except for the central mesenterectomy involving the SMP, we conclude that the denervation causes this significantly different stool pattern. Within the first month, the frequency and consistency nearly normalize. This work adds to our general understanding of the consequences of superior mesenteric nerve plexus denervation. Knowing how BF is affected will also be paramount to our patients, should the D3 resection become the recommended preferred operation for right-sided colon cancer. The study design does not allow us to draw any conclusions about the mechanisms of the postoperative diarrhea nor the normalization. A generally accepted hypothesis for diarrhea after extrinsic denervation is a loss of the sympathetic nerves’ dampening effect leading to a parasympathetic overactivity [Citation13]. Given the tremendous complexity that has been revealed in recent decades, this is, of course, a simplification. Since SMP is part of the hard wiring of the microbiome–gut–brain axis, nerve injury could influence this axis in many ways. Moreover, enhanced transit could affect the microbiome. Nevertheless, compensatory mechanisms, not a reinnervation must cause the early rapid improvement observed in the graphs. The bowel is known to have remarkable plasticity. The constant fast renewal of the endothelium enables rapid modifications related to the number and differentiation of the cells. These modulations can change the absorptive and secreting functions within a few days [Citation14]. The early improvement is probably a result of this adaptation, adjusting for the significantly reduced postoperative transit time documented in the study with the WMC [Citation6]. Previous animal studies have shown that the ability to adapt absorptive and morphometric remains after extrinsic denervation [Citation15,Citation16].

Whereas this early rapid improvement most certainly reflects compensatory mechanisms, the late and slow normalization leading up to the results at the second interview (and the last test in the motility study) [Citation6] might be a result of an adaptation of the remaining autonomic nervous system (ENS and/or remaining nerves in the SMP following branches of the SMA emerging proximal to the injury) or even reinnervation [Citation17,Citation18]. Our results reveal that the D3-group still has looser consistency in the long-term follow-up than the D2-group (p=.039), which accords with our previous studies and theory. Nevertheless, it does not affect stool frequency or QoL.

Strengths and limitations

The prospective design and the use of the diary to provide detailed day-by-day information concerning stool frequency and consistency are important strengths. The main limitation of the study was the relatively small control group (D2). The reason is that the extended D3-mesenterectomy has become our standard procedure, limiting the number of D2-patients. All patients who are 75 years or younger are offered the new procedure. Since most of the younger patients receive the extended D3-mesenterectomy, the control group is slightly older than the experimental group. During a lifetime, one can expect a certain change in the bowel pattern. The short period represented by the age difference between the groups (6.77 years), will, in this context, hardly constitute a significant change in intestinal function in such a highly selected group of patients [Citation19]. The small difference in length of the small bowel resection accounts for only about 1% of the total length of the small bowel and is, therefore, not expected to affect the results. The overall dropout rate was high, but was similar between the groups. The age difference can perhaps explain the slightly higher dropout rate in the D2-group.

Conclusion

This study shows that patients undergoing right colectomy with extended D3-mesenterectomy – in the early postoperative period – experience significantly higher stool numbers per day with looser consistency than patients undergoing the traditional D2-mesenterectomy. This finding correlates well with the earlier mentioned motility study, which revealed a significantly reduced small bowel transit time 3 weeks after the procedure [Citation5]. The fast, steady improvement beginning around ten days after surgery probably reflects the great plasticity of the bowel to compensate for the reduced transit time. The long-time results concerning BF and QoL are comparable in the groups.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Shinohara H, Hasegawa S, Tsunoda S, et al. Principles of anatomy. In: Sakai Y, editor. Laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. Tokyo: Springer Japan; 2016. p. 1–16.

- Ignjatovic D, Bergamaschi R. Defining the extent of mesenterectomy in right colectomy: a controversy.Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(7):649.

- Nesgaard JM, Stimec BV, Bakka AO, et al. Navigating the mesentery. A comparative pre- and per-operative visualization of the vascular anatomy. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17(9):810–818.

- Thorsen Y, Stimec B, Andersen SN, et al. Bowel function and quality of life after superior mesenteric nerve plexus transection in right colectomy with D3 extended mesenterectomy. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(7):445–453.

- Thorsen Y, Stimec BV, Lindstrom JC et al. The effect of vascular anatomy and gender on bowel function after right colectomy with extended D3-mesenterectomy. Ann Laparosc Endosc Surg. 2019;4:71.

- Thorsen Y, Stimec BV, Lindstrom JC, et al. Bowel motility after injury to the superior mesenteric plexus during D3 extended mesenterectomy. J Surg Res. 2019;239:115–124.

- Gaupset R, Nesgaard JM, Kazaryan AM, et al. Introducing anatomically correct CT-guided laparoscopic right colectomy with D3 anterior posterior extended mesenterectomy: initial experience and technical pitfalls. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018;28(10):1174–1182.

- Willard CD, Kjaestad E, Stimec BV, et al. Preoperative anatomical road mapping reduces variability of operating time, estimated blood loss, and lymph node yield in right colectomy with extended D3 mesenterectomy for cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34(1):151–160.

- McMillan SC, Bartkowski-Doda L “Measuring bowel elimination.” Instruments for clinical research in health care. Wilsonville (OR): Jones & Bartlett Inc.; 1997.

- Sandblom G, Videhult P, Karlson BM, et al. Validation of gastrointestinal quality of life index in Swedish for assessing the impact of gallstones on health-related quality of life. Value Health. 2009;12(1):181–184.

- Jacobsen EL, Bye A, Aass N, et al. Norwegian reference values for the Short-Form Health Survey 36: development over time. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1213–1215.

- Yuan L, O’Grady G, Milne T, et al. Prospective comparison of return of bowel function after left versus right colectomy. ANZ J Surg. 2018;88(4):E242–E247.

- Toukhy ME, Campkin NT. Severe diarrhea following neurolytic coeliac plexus block: case report and literature review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28(7):511–514.

- Le Gall M, Thenet S, Aguanno D, et al. Intestinal plasticity in response to nutrition and gastrointestinal surgery. Nutr Rev. 2019;77(3):129–143.

- Sarr MG, Duenes JA, Walters AM. Jejunal and ileal absorptive function after a model of canine jejunoileal autotransplantation. J Surg Res. 1991;51(3):233–239.

- Libsch KD, Duininck TM, Sarr MG. Ileal resection enhances jejunal absorptive adaptation for water and electrolytes to extrinsic denervation: implications for segmental small bowel transplantation. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(3):502–507.

- Fatima J, Houghton SG, Sarr MG. Development of a simple model of extrinsic denervation of the small bowel in mouse. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(8):1052–1056.

- Ridolfi TJ, Tong WD, Kosinski L, et al. Recovery of colonic transit following extrinsic nerve damage in rats. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(6):678–683.

- Harari D, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, et al. Bowel habit in relation to age and gender. Findings from the National Health Interview Survey and clinical implications. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(3):315–320.