Abstract

Objective

Although prophylactic clip closure after endoscopic mucosal resection may prevent delayed bleeding, information regarding colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (CR-ESD) is lacking. Therefore, this study evaluated the effect of prophylactic clip closure on delayed bleeding rate after CR-ESD.

Materials and methods

A total of 614 CR-ESD procedures performed in 561 patients were retrospectively reviewed. The primary outcome, which was delayed bleeding rate, was analyzed between the prophylactic clip closure and non-closure groups. Furthermore, the predictors of delayed bleeding were also evaluated.

Results

The patients were divided into the clip closure group (n = 275) and non-closure group (n = 339). Delayed bleeding rate was significantly lower in the closure group than in non-closure group (6 cases [2.2%] vs. 20 cases [5.9%], p = .026). The univariate logistic regression analyses revealed that delayed bleeding was significantly associated with laterally spreading tumor-granular-nodular mixed type (LST-G-Mix; odds ratio [OR], 3.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.70–8.34; p = .001). By contrast, prophylactic clip closure was significantly associated with low delayed bleeding rate (OR, 0.36; 95%CI, 0.14–0.90; p = .029). The multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed LST-G-Mix as a significant independent delayed bleeding predictor (OR, 3.25; 95%CI, 1.45–7.32; p = .004), whereas, prophylactic clip closure was identified as a significant independent preventive factor of delayed bleeding (OR, 0.39; 95%CI, 0.15–1.00; p = .049).

Conclusions

Prophylactic clip closure after CR-ESD is associated with low delayed bleeding rate. LST-G-Mix promotes delayed bleeding, and performing prophylactic clip closure may be advisable.

Introduction

Currently, endoscopic resection is a widely accepted treatment for neoplasms in the colorectum, as it leads to reduced incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer [Citation1]. Although endoscopic resection is recognized as an easy and effective procedure, it can lead to adverse events, particularly delayed bleeding. Conventionally, prophylactic clip closure for an artificial ulcer wound after endoscopic resection was performed to prevent delayed bleeding; however, the efficacy of prophylactic clip closure has been controversial [Citation2–30].

Recently, three large randomized controlled trials reported that prophylactic clip closure was ineffective in preventing delayed bleeding in lesions ≥10 mm in size [Citation21] but was effective for lesions ≥20 mm in size [Citation22,Citation23]. Moreover, other observational trials also reported a similar result; therefore, prophylactic clip closure is considered effective for lesions ≥20 mm in size [Citation3,Citation4,Citation9,Citation12,Citation22,Citation23,Citation26,Citation28].

Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (CR-ESD) has been increasingly used for en bloc resection of large and depressed colorectal superficial neoplasms, resulting in low local recurrence rates, high-quality pathological specimens for accurate histological diagnosis, and curative resection of early carcinoma [Citation31]. Most lesions suitable for CR-ESD are ≥20 mm in size.

Therefore, we hypothesized that prophylactic clipping may also be useful for preventing delayed bleeding after CR-ESD. Although several studies have reported regarding the efficacy of prophylactic clip closure in artificial ulcer wounds after CR-ESD [Citation5,Citation16,Citation18–20,Citation24,Citation27,Citation29,Citation32], only few studies report decreased delayed bleeding rates [Citation18,Citation19,Citation29]. Additionally, with the exception of the meta-analysis report, these reports had small sample sizes and the analyses were univariate. In this study, we retrospectively investigated the efficacy of prophylactic clip closure after 614 CR-ESDs on delayed bleeding using multivariate logistic regression analyses.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

We retrospectively reviewed the outcomes for 614 cases of CR-ESD performed in 561 patients between May 2012 and September 2020 at Asahi General Hospital, Japan. Indications for CR-ESD were based on the guidelines proposed by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society (JGES) [Citation33]. The indications were as follows: (I) lesions for which en bloc resection with snare endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) was difficult to apply; (II) mucosal tumors with submucosal fibrosis; (III) sporadic tumors in conditions of chronic inflammation such as ulcerative colitis; (IV) local residual or recurrent early carcinomas after endoscopic resection. The uncompleted CR-ESD cases were excluded from review. This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of Asahi General Hospital (21 July 2020), and written informed consent for the procedure was obtained from all the patients.

Antithrombotic medicine

For patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment, the decision to continue or discontinue treatment was made on the basis of the guidelines proposed by the JGES [Citation34,Citation35]. The patients with high risk of thromboembolism who were undergoing aspirin monotherapy continued oral administration. For the patients with low risk of thromboembolism, aspirin was withdrawn for 3 to 5 days.

The withdrawal of administration was required for non-aspirin antiplatelet agent users. Thienopyridine derivatives were withdrawn for 5–7 days, whereas all the other antiplatelet agents for 1 day. The agents were replaced with aspirin or cilostazol in the patients at high risk of thromboembolism and multiple antiplatelet agent users.

The patients who received anticoagulants such as direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) continued to receive DOAC until the day prior to the procedure and discontinued the therapy in the morning of the procedure. Continued warfarin treatment (maintaining the INR within the therapeutic range), or heparin or DOAC replacement were recommended for warfarin users. For the patients who were taking DOACs in combination with antiplatelet agents, DOAC administration was discontinued in the morning of the procedure. Furthermore, use of aspirin or cilostazol was allowed for antiplatelet therapy.

ESD procedure

All the procedures were performed by three board-certified fellows of the JGES. The patients were admitted 1 day prior to CR-ESD and remained in the hospital for approximately 5–7 days. We performed bowel preparation using 2 L of isotonic polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution (Niflec; EA Pharma Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) in the morning of the ESD procedure. GIF-Q260J (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) for rectal lesions, and PCF-Q260JI (Olympus) or PCF-H290TI (Olympus) for lesions from the sigmoid colon to the cecum was used with carbon dioxide insufflation.

Only for unclear margins such as sessile serrated lesion (SSL), we used an argon plasma coagulation probe for placement of marking dots along the target lesion circumference to indicate the margins. First, we injected 0.4% sodium hyaluronate (MucoUp; Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan) with a small amount of indigo carmine and epinephrine in the submucosal layer by using a 26-gauge injection needle. Next, a circumferential incision was made from the anal side with Stag-Beetle Knife Jr (SB Knife Jr, Sumitomo Bakelite Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). For large lesions, a partial circumferential incision was frequently performed to define the oral end of the lesion. The circumferential incision was extended, and submucosal dissection was performed; these steps were repeated in an alternating sequence until the entire lesion was resected. The current was passed using a high-frequency generator (VIO300D; Erbe Elektromedizin, Tübingen, Germany). No sedatives and antibiotics were routinely used. Zeoclip (ZP-CHS; Zeon Medical Inc., Tokyo, Japan) or EZ Clip (HX-610-135S; Olympus) was used for prophylactic clip closure as needed.

Protocol for artificial ulcer wound after ESD

Prophylactic clip closure was performed as much as possible for the first 368 cases (treated between May 2012 and December 2017), but was not routinely performed for the later 246 cases (treated between January 2018 and September 2020). In the later 246 cases, prophylactic clip closure was performed only for cases of muscle layer injury that occurred during the procedure and high-risk bleeding cases such as antithrombotic medicine use. Prophylactic coagulation for visible vessels was not routinely performed. The clip closure was performed from edge to center. Then, if the wound was too large to be sutured, the clip closure was performed from the contralateral edge toward the center, leaving the center open. The patients were divided into closure and non-closure groups according to wound defect appearance. The patients with complete closure were defined as the closure group, while those with partial closure and non-closure were defined as the non-closure group.

Histopathological assessment

Histopathological diagnosis was performed in accordance with the guidelines for CR-ESD proposed by the JGES [Citation33]. Complete resection was defined as an en bloc resection where both the horizontal and vertical margins were negative. For en bloc resection specimens, we considered adenomas with unclear lateral margins and an expected lateral burning effect as a margin negative. Curative resection was defined as complete resection and fulfillment of all the following characteristics: (I) differentiated or papillary carcinoma; (II) no lymphovascular invasion; (III) submucosal invasion depth < 1000 µm; and (IV) grade 1 budding. We referenced the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer [Citation36].

Outcome definitions

The primary outcome was delayed bleeding rate. The secondary outcomes were predictors of delayed bleeding. Delayed bleeding was defined as hematochezia requiring endoscopic hemostasis or blood transfusion or leading to a reduction of ≥2 g/dL in hemoglobin level.

Statistical analyses

Patient characteristics and treatment outcomes were compared using the Fisher exact and chi-square tests, as appropriate. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to clarify the risk factors of delayed bleeding after CR-ESD. These analyses were conducted at the Clinical Research Support Center of Asahi General Hospital. A two-sided p value < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP version 14.0.2 software (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Patients’ clinical characteristics between the closure and non-closure groups

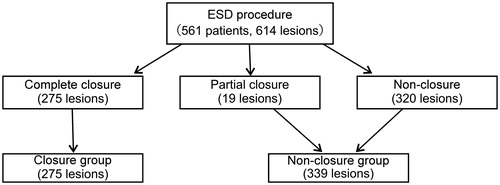

The comparison of the patients’ clinical characteristics between the closure and non-closure groups is presented in . Furthermore, the patient flowchart regarding the wound defect appearance is shown in . Overall, 561 patients were treated with 614 cases of ESD. Regarding wound defect appearance, 275 cases were complete closure, 19 cases were partial closure, and 320 cases were non-closure. Lastly, the patients were divided into the closure (n = 275) and non-closure groups (n = 339). Antiplatelet agent and anticoagulant users were not significantly different between the groups. The number of patients who had heparin replacement was higher in the closure group than in the non-closure group (2.9% vs. 0.3%, p = .013).

Table 1. Patient clinical characteristics between the closure and non-closure groups.

Tumor characteristics between the closure and non-closure groups

The comparison of tumor characteristics between the closure and non-closure groups is shown in . The tumor was predominantly located in the rectum in the non-closure group than in the closure group (31.6% vs. 23.6%, p = .031). With regard to the macroscopic type, the prevalence of the laterally spreading tumor-non-granular-pseudo-depressed type (LST-NG-PD) and protruding lesion was higher in the closure group, whereas laterally spreading tumor-non-granular-flat-elevated type (LST-NG-F) was higher in the non-closure group (p <.001). A high prevalence of SSL was found in the non-closure group (p = .025). The tumor depth of invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and budding grade showed no significant differences between the groups.

Table 2. Tumor characteristics between the closure and non-closure groups.

Treatment outcome between the closure and non-closure groups

The treatment outcomes compared between the closure and non-closure group are listed in . The longer procedure time (p <.001), larger tumor and specimen size (p <.001), and more severe fibrosis (p <.001) were found in the non-closure group. The resection speed, en bloc resection rate, complete resection rate, curative resection rate, and perforation rate showed no significant differences between the groups. The delayed bleeding rate was significantly lower in the closure group than in the non-closure group (2.2% vs. 5.9%, p = .026). All the cases were treated with emergency endoscopic hemostasis using clips, and surgery or blood transfusion were unnecessary. Among 62 aspirin users, 30 patients continued oral administration, while 32 patients discontinued oral administration. Delayed bleeding occurred in two patients in the continued group (6.7%), whereas one patient in the discontinued group (3.1%) showed no significant difference in delayed bleeding. The numbers of patients who felt abdominal tenderness and had post-ESD coagulation syndrome were not significantly different between the groups.

Table 3. Treatment outcomes between the closure and non-closure groups.

Predictors of delayed bleeding after CR-ESD

The analyses of the predictors that induced delayed bleeding after CR-ESD are shown in . To identify the factors that led to the frequency of delayed bleeding after CR-ESD, the occurrence rate of delayed bleeding was compared between the closure (n = 6) and non-closure groups (n = 20). The univariate logistic regression analyses revealed that delayed bleeding after CR-ESD was significantly associated with the laterally spreading tumor-granular-nodular mixed type (LST-G-Mix; odds ratio [OR], 3.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.70–8.34; p = .001). By contrast, prophylactic clip closure was significantly associated with a low occurrence rate of delayed bleeding (OR, 0.36; 95%CI, 0.14–0.90; p = .029).

Table 4. Predictors of delayed bleeding after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection.

Furthermore, the multivariate logistic regression analyses revealed that LST-G-Mix was a significant independent predictor of delayed bleeding (OR, 3.25; 95%CI, 1.45–7.32; p = .004). On the other hand, prophylactic clip closure was identified as a significant independent preventive factor of delayed bleeding (OR, 0.39; 95%CI, 0.15–1.00; p = .049). Tumors ≥20 mm in size were not a significant risk factor of the occurrence rate of delayed bleeding.

Discussion

In this study, we observed that the delayed bleeding rate was significantly lower in the closure group than in the non-closure group. Moreover, the multivariate analyses using logistic regression revealed that the prophylactic clip closure after CR-ESD was an independent factor that significantly reduced the delayed bleeding rate, while LST-G-Mix was identified as a significant independent promotive factor of delayed bleeding.

We observed that the delayed bleeding rate was significantly lower in the closure group than in the non-closure group (2.2% vs. 5.9%, p = .026). Prophylactic clip closure after CR-ESD was the only independent factor that significantly reduced the delayed bleeding rate. Several previous studies regarding EMR reported that prophylactic clip closure was likely to be associated with low delayed bleeding rate for large lesions such as those ≥20 mm in size [Citation3,Citation4,Citation9,Citation12,Citation22,Citation23,Citation26,Citation28]. ESD for a large lesion takes a longer procedure time, which induces enlarged post-ESD ulcers due to a lot of thermal damage during dissection. Furthermore, large lesions have more multiple vessels; therefore, these factors may cause delayed bleeding and efficacy of prophylactic clip closure. In this study, the mean tumor and specimen sizes were 28.7 ± 14.1 and 39.4 ± 14.3 mm, respectively. These lesions were ≥20 mm, appropriate for CR-ESD; therefore, prophylactic clip closure after CR-ESD was expected to lead to decreased delayed bleeding rate. On the other hand, as precoagulation and prophylactic hemostasis could be performed during ESD, delayed bleeding might be prevented as compared with EMR; therefore, the necessity of prophylactic clip closure after CR-ESD remains controversial.

Although four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) validated the efficacy of prophylactic clip closure after CR-ESD, no trials have set delayed bleeding rate as the primary endpoint. No significant difference was found in delayed bleeding rate [Citation24,Citation27,Citation32]. Only Zhang et al. set adverse events as the primary endpoint and reported that prophylactic clip closure after ESD and EMR significantly decreased the delayed bleeding rate [Citation9]. However, as the study included not only ESD but also EMR cases, its limitation was its small sample size of ESD cases. Therefore, the hemostatic effect of prophylactic clip closure after only ESD remains controversial [Citation10]. However, according to our data, including ESD-only cases, we revealed that prophylactic clip closure after ESD was associated with low delayed bleeding rate; therefore, we recommend that prophylactic clip closure should be performed also after ESD.

Although the previous reports suggested that tumor size, location, and use of antiplatelet agents are the risk factors of delayed bleeding, these were not relevant [Citation37–40]. This study validated CR-ESD using scissor-type knives such as SB Knife Jr. SB Knife Jr also has a function as hemostatic forceps and enables hemostasis or precoagulation without device replacement and may lead to low delayed bleeding rate as compared with the conventional needle-type knife [Citation41,Citation42]. These facts might be the reason for the small number of delayed bleeding cases, which did not result in significant differences in risk factors. Alternatively, our multivariate analyses using logistic regression revealed LST-G-Mix as a significant independent promotive factor of delayed bleeding. LST-G-Mix has abundant blood flow in the nodal area, which may have affected the delayed bleeding. In the future, performing prophylactic clip closure may be advisable, especially in LST-G-Mix. Furthermore, nodular lesions such as LST-G-Mix or protruding lesions induce fibrosis attributed to the mechanical force generated between the submucosa and the muscle layer as a result of intestinal peristalsis, which lead to extreme difficulty of the procedure [Citation43]. Therefore, it may be preferable to treat LST-G-Mix by experts.

This study has several limitations. First, differences in tumor characteristics and treatment outcomes between the closure and non-closure groups were observed owing to policies such as performing prophylactic clip closure as much as possible for the first 368 cases, while not performing prophylactic clip closure in the later 246 cases. The learning curve might have led to the many cases of high difficulty level, such as large and severe fibrotic lesions to the later period. As a result, more cases in the non-closure group might be observed in the later period, which leads to a high delayed bleeding rate. Additionally, larger lesions were difficult to close, and as a result, high-risk bleeding cases such as those with larger lesions were designated into the non-closure group. Second, the difference in patient characteristics between the closure and non-closure group was also observed. The closure group tended to have high-risk bleeding cases such as those with heparin replacement. The endoscopists’ potential desire might lead to perform prophylactic clip closure in high-risk cases. Although antithrombotic drugs were withdrawn or continued in accordance with the guidelines proposed by the JGES, discontinuation or continuation of antithrombotic drugs may have been biased by the presence or absence of medical history such as cardiovascular disease. Third, the number of rectal lesions was lower in the closure group. The rectal mucosa was tense owing to the wide lumen, which led to the highly difficult prophylactic clip closure. This was expected to have led to non-closure or partial closure. From these reasons, selection bias was unavoidable. However, the multivariate analyses revealed that tumor size, fibrosis, antithrombotic user, and rectal lesion were not independent factors that significantly induced delayed bleeding. Therefore, we believe these problems are acceptable.

Furthermore, this study did not refer to cost-effectiveness and labor. Although this study revealed that prophylactic clip closure significantly reduced delayed bleeding, all bleeding cases were not fatal, and hemostasis was successful using endoscopy. The previous report suggested that prophylactic clip closure after endoscopic resection of large colon polyps, particularly those in the right colon segment, was cost saving but requires clips that cost < $100 [Citation44]. However, multiple clipping is frequently essential for complete closure of CR-ESD ulcers. Therefore, the meaning of prophylactic clip closure remains controversial with regard to cost-effectiveness and labor.

In conclusion, prophylactic clip closure after CR-ESD is associated with low delayed bleeding rate. LST-G-Mix is a promotive factor of delayed bleeding, and performing prophylactic clip closure may be advisable, especially for LST-G-Mix. Multicenter prospective studies are needed to confirm its efficacy.

Author contributions

A.M. and T.K designed the study, and wrote the draft of the manuscript. Y.S. contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. M.K., A.N., E.I., H.S., Y.S., and K.S. assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Clinical Research Center at Asahi General Hospital, Asahi, Japan. We thank all support team members.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O'Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(8):687–696.

- Shioji K, Suzuki Y, Kobayashi M, et al. Prophylactic clip application does not decrease delayed bleeding after colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57(6):691–694.

- Matsumoto M, Fukunaga S, Saito Y, et al. Risk factors for delayed bleeding after endoscopic resection for large colorectal tumors. Jpn J Clin Oncol.2012;42(11):1028–1034.

- Liaquat H, Rohn E, Rex DK. Prophylactic clip closure reduced the risk of delayed postpolypectomy hemorrhage: experience in 277 clipped large sessile or flat colorectal lesions and 247 control lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77(3):401–407.

- Fujihara S, Mori H, Kobara H, et al. The efficacy and safety of prophylactic closure for a large mucosal defect after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Oncol Rep. 2013;30(1):85–90.

- Feagins LA, Nguyen AD, Iqbal R, et al. The prophylactic placement of hemoclips to prevent delayed post-polypectomy bleeding: an unnecessary practice? A case control study. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(4):823–828.

- Dokoshi T, Fujiya M, Tanaka K, et al. A randomized study on the effectiveness of prophylactic clipping during endoscopic resection of colon polyps for the prevention of delayed bleeding. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:490272.

- Mori H, Kobara H, Nishiyama N, et al. Simple and reliable treatment for post-EMR artificial ulcer floor with snare cauterization for 10- to 20-mm colorectal polyps: a randomized prospective study (with video). Surg Endosc. 2015;29(9):2818–2824.

- Zhang QS, Han B, Xu JH, et al. Clip closure of defect after endoscopic resection in patients with larger colorectal tumors decreased the adverse events. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82(5):904–909.

- Burgess NG, Bourke MJ. Mucosal colonic defect post EMR or ESD: to close or not? Endosc Int Open. 2016;4(10):E1073–E1074.

- Matsumoto M, Kato M, Oba K, et al. Multicenter randomized controlled study to assess the effect of prophylactic clipping on post-polypectomy delayed bleeding. Dig Endosc. 2016;28(5):570–576.

- Boumitri C, Mir FA, Ashraf I, et al. Prophylactic clipping and post-polypectomy bleeding: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Ann Gastroenterol. 2016;29(4):502–508.

- Park CH, Jung YS, Nam E, et al. Comparison of efficacy of prophylactic endoscopic therapies for postpolypectomy bleeding in the colorectum: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(9):1230–1243.

- Albéniz E, Fraile M, Ibáñez B, et al. A scoring system to determine risk of delayed bleeding after endoscopic mucosal resection of large colorectal lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(8):1140–1147.

- Nishizawa T, Suzuki H, Goto O, et al. Effect of prophylactic clipping in colorectal endoscopic resection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. United European Gastroenterol J. 2017;5(6):859–867.

- Harada H, Suehiro S, Murakami D, et al. Clinical impact of prophylactic clip closure of mucosal defects after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endosc Int Open. 2017;05(12):E1165–E1171.

- Mangira D, Ket SN, Majeed A, et al. Postpolypectomy prophylactic clip closure for the prevention of delayed postpolypectomy bleeding: a systematic review. JGH Open. 2018;2(3):105–110.

- Ogiyama H, Tsutsui S, Murayama Y, et al. Prophylactic clip closure may reduce the risk of delayed bleeding after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6(5):E582–E588.

- Yamamoto K, Shimoda R, Ogata S, et al. Perforation and postoperative bleeding associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection in colorectal tumors: an analysis of 398 lesions treated in Saga, Japan. Intern Med. 2018;57(15):2115–2122.

- Yamasaki Y, Takeuchi Y, Iwatsubo T, et al. Line-assisted complete closure for a large mucosal defect after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection decreased post-electrocoagulation syndrome. Dig Endosc. 2018;30(5):633–641.

- Feagins LA, Smith AD, Kim D, et al. Efficacy of prophylactic hemoclips in prevention of delayed post-polypectomy bleeding in patients with large colonic polyps. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(4):967–976.

- Pohl H, Grimm IS, Moyer MT, et al. Clip closure prevents bleeding after endoscopic resection of large colon polyps in a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(4):977–984.

- Albéniz E, Álvarez MA, Espinós JC, et al. Clip closure after resection of large colorectal lesions with substantial risk of bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(5):1213–1221.

- Lee SP, Sung IK, Kim JH, et al. Effect of prophylactic endoscopic closure for an artificial ulceration after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(10):1291–1299.

- Forbes N, Frehlich L, James MT, et al. Routine prophylactic endoscopic clipping is not efficacious in the prevention of delayed post-polypectomy bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2019;2(3):105–117.

- Ayoub F, Westerveld DR, Forde JJ, et al. Effect of prophylactic clip placement following endoscopic mucosal resection of large colorectal lesions on delayed polypectomy bleeding: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(18):2251–2263.

- Nomura S, Shimura T, Katano T, et al. A multicenter, single-blind randomized controlled trial of endoscopic clipping closure for preventing coagulation syndrome after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(4):859–867.

- Forbes N, Hilsden RJ, Lethebe BC, et al. Prophylactic endoscopic clipping does not prevent delayed postpolypectomy bleeding in routine clinical practice: a propensity score-matched cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(5):774–782.

- Liu M, Zhang Y, Wang Y, et al. Effect of prophylactic closure on adverse events after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35(11):1869–1877.

- Inoue T, Ishihara R, Nishida T, et al. Prophylactic clipping not effective in preventing post-polypectomy bleeding for < 20-mm colon polyps: a multicenter, open-label, randomized controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36(2):383–390.

- Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47(9):829–854.

- Osada T, Sakamoto N, Ritsuno H, et al. Closure with clips to accelerate healing of mucosal defects caused by colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(10):4438–4444.

- Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y, et al. Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society guidelines for colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal resection. Dig Endosc. 2020;32(2):219–239.

- Fujimoto K, Fujishiro M, Kato M, Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society, et al. Guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment. Dig Endosc. 2014;26(1):1–14.

- Kato M, Uedo N, Hokimoto S, et al. Guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment: 2017 Appendix on Anticoagulants Including Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Dig Endosc. 2018;30(4):433–440.

- Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25(1):1–42.

- Suzuki S, Chino A, Kishihara T, et al. Risk factors for bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of colorectal neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(7):1839–1845.

- Terasaki M, Tanaka S, Shigita K, et al. Risk factors for delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal neoplasms. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29(7):877–882.

- Ogasawara N, Yoshimine T, Noda H, et al. Clinical risk factors for delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal tumors in Japanese patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(12):1407–1414.

- Seo M, Song EM, Cho JW, et al. A risk-scoring model for the prediction of delayed bleeding after colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89(5):990–998.

- Kuwai T, Yamaguchi T, Imagawa H, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early colorectal neoplasms with a monopolar scissor-type knife: short- to long-term outcomes. Endoscopy. 2017;49(9):913–918.

- Miyakawa A, Kuwai T, Sakuma Y, et al. Learning curve for endoscopic submucosal dissection of early colorectal neoplasms with a monopolar scissor-type knife: use of the cumulative sum method. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(10):1234–1242.

- Toyonaga T, Tanaka S, Man-I M, et al. Clinical significance of the muscle-retracting sign during colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3(03):E246–E251.

- Shah ED, Pohl H, Rex DK, et al. Valuing innovative endoscopic techniques: prophylactic clip closure after endoscopic resection of large colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(6):1353–1360.