Abstract

Background

Some studies have suggested a reduced life expectancy in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) compared with the general population. The evidence, however, is inconsistent.

Aims

Prompted by such studies, we studied survival of CD patients in Örebro county, Sweden.

Methods

From the medical records, we identified all patients diagnosed with CD during 1963–2010 with follow-up to the end of 2011. We estimated: overall survival, net and crude probabilities of dying from CD, relative survival ratio (RSR), and excess mortality rate ratios (EMRR) at 10-year follow-up.

Results

The study included 492 patients (226 males, 266 females). Median age at diagnosis was 32 years (3–87). Net and crude probabilities of dying from CD increased with increasing age and were higher for women. Net survival of patients aged ≥60 at diagnosis was worse for patients diagnosed during 1963–1985 (54%) than for patients diagnosed during 1986–1999 (88%) or 2000–2010 (93%). Overall, CD patients’ survival was comparable to that in the general population [RSR = 0.98; 95% CI: (0.95–1.00)]. However, significantly lower than expected survival was suggested for female patients aged ≥60 diagnosed during the 1963–1985 [RSR = 0.47 (0.07–0.95)]. The adjusted model suggested that, compared with diagnostic period 1963–1985, disease-related excess mortality declined during 2000–2010 [EMRR = 0.36 (0.07–1.96)]; and age ≥60 at diagnosis [EMRR = 7.99 (1.64–39.00), reference: age 40–59], female sex [EMRR = 4.16 (0.62–27.85)], colonic localization [EMRR = 4.20 (0.81–21.88), reference: ileal localization], and stricturing/penetrating disease [EMRR = 2.56 (0.52–12.58), reference: inflammatory disease behaviour] were associated with poorer survival.

Conclusion

CD-related excess mortality may vary with diagnostic period, age, sex and disease phenotype.

There is inconsistent evidence on life expectancy of patients with Crohn’s disease

Crohn’s disease-specific survival improved over time.

Earlier diagnosis period, older age at diagnosis, female sex, colonic disease and complicated disease behaviour seems to be associated with excess Crohn’s disease-related mortality.

Key summary

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a progressive disease characterised by chronic transmural inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract that may cause chronic diarrhoea, strictures and abscesses. The disease course is heterogeneous and varies from an indolent disease with a few flares to a severe course with repeated surgery.

Previous studies suggest that CD mortality rates may range from 30% lower [Citation1] to 70% higher [Citation2,Citation3] than in the general population and that CD survival may have improved over time [Citation4–10]. Few studies, however, have examined temporal trends in CD survival in the ‘modern era’ of targeted therapies. A recent study by Olen et al. found that inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) related deaths have declined over time [Citation11]. However, given that patients with Crohn’s disease were identified from the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes, it is unknown if the study findings are applicable to all phenotypes of Crohn’s disease.

We conducted a regional, population-based study with the aim to assess the 10-year survival in patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease during 1963–2010 compared with the general population of the same demographic structure and to identify factors associated with excess mortality. We estimated all-cause mortality and Crohn’s disease-specific mortality and also examined whether Crohn’s disease-specific survival had changed over three predefined diagnostic periods.

Materials and methods

Study population and setting

We identified all incident patients diagnosed with CD between January 1, 1963, and December 31, 2010 within the Örebro University Hospital primary catchment area, [Citation12] comprising 189603 inhabitants in the year 2010. The diagnosis was confirmed by evaluation of medical notes. The cohort and the study region have been described in detail previously [Citation12,Citation13]. Briefly, information about sex, date of birth, date of diagnosis, disease location, and clinical characteristics according to the Montreal classification [Citation14] were extracted from the IBD cohort database of Örebro University Hospital and from medical records. A total of 494 patients with CD were identified, of whom two were excluded from the current study due to missing information on disease behaviour.

Mortality and follow-up

Information on the date and the underlying cause of death was obtained from the Cause of Death Register [Citation15] using each patient’s unique personal identity number. Patients were followed from the date of diagnosis until death, emigration, or end of follow-up on December 31, 2011, whichever occurred first.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were tabulated by calendar period of diagnosis and compared using the χ2 test, Fisher exact test, or median test as appropriate based on measurement type and distribution. The calendar periods were chosen in order to obtain a more even patient distribution and to facilitate detection of effects on survival resulting from changes in diagnostic criteria and treatment of CD.

The investigated measures of survival and mortality included: overall survival, net survival, relative survival ratio (RSR), and crude mortality due to Crohn’s disease as well as due to other causes.

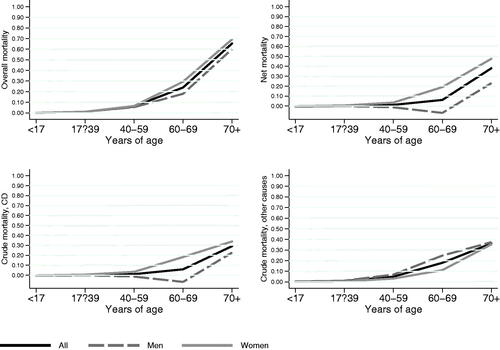

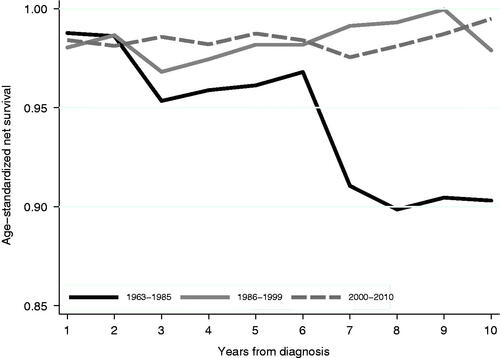

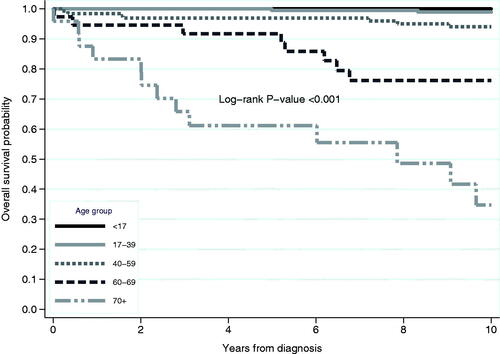

Since survival strongly depends on age, Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival (the probability that a patient is still alive at a certain time point after CD diagnosis) were computed by age groups (<17, 17–39, 40–59, 60–69, and ≥70 years at diagnosis). Net survival, the probability of survival where CD is the only possible cause of death, was estimated using the Pohar Perme estimator of net survival [Citation16]. Crude probabilities of dying of CD or other causes, which take competing risk of death into account, were estimated using the Cronin and Feuer method [Citation17]. While crude probabilities of death could be more informative for patients and clinicians, net survival (or net mortality, which is 1 minus net survival) was used to compare the Crohn’s disease-specific survival across the three diagnostic periods. As it is unaffected by hazard due to other causes, net-survival is the recommended measure for comparing disease-specific survival of different populations defined according to time period, geography, or other characteristics. Since net survival generally depends on age at diagnosis, we computed age-stratified and age-standardised estimates.

Relative survival ratio (RSR), a measure of total excess mortality associated with a diagnosis of CD, compares the overall survival of the CD patients to the expected overall survival in a disease-free but otherwise comparable general population [Citation17]. Cumulative expected survival was estimated using Swedish general population life-tables matched to the CD cohort by age, sex, and calendar year applying the Ederer I method [Citation16,Citation17]. Relative survival analysis was stratified by sex due to inherent sex-based differences in death rates. An RSR of 1.00 implies that the survival of CD patients is just as good or as poor as that of the reference population. An RSR <1.00, indicates a worse survival than expected, and it is assumed that the excess mortality is due to the disease under the study. An RSR >1.00 is observed if the patient group has a lower mortality rate than that expected. A generalised linear model with a Poisson error structure [Citation17,Citation18] was used to model the effect of age at diagnosis, sex, calendar year at diagnosis, as well as disease location and behaviour on the excess mortality rate ratio (EMRR). The analysis was restricted to patients aged ≥40 at diagnosis.

All calculations were performed using STATA software version 14SE (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). The study was approved by the Uppsala Regional Ethics Committee (2010/304 and 2010/304/1).

Results

Characteristics of the patients with Crohn’s disease

Basic demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients with Crohn’s disease (n = 492: 226 men and 266 women) are shown in . Compared with patients diagnosed during the earlier calendar period of 1963–1985, patients diagnosed between 1986–2010 had a higher median age at diagnosis and were more likely to have inflammatory (B1) disease behaviour.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in 1963 to 2010 in Örebro, Sweden.

Survival and mortality estimates

In over 4,075 person-years of follow-up, 30 patients (13 men and 17 women: 6.1%) with Crohn’s disease died. The leading cause of death was cardiovascular disease followed by complications of Crohn’s disease (Supplementary Table 5). The observed 10-year overall survival was 100% for patients aged <17 years at diagnosis, 99% for patients aged 17–39 years, 94% for patients aged 40–59 years and 76% for patients aged 60–69 (). Patients aged 70 or above at diagnosis () had the lowest overall survival (35%) with a median survival of 7.9 years. Ten-year overall survival improved over the three calendar periods for both younger and older male and female patients ().

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier estimate of overall survival over 10 years of follow-up by age groups for patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in 1963 to 2010 in Örebro, Sweden.

Table 2. Crude and net probability of death by sex and age for patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in 1963 to 2010 in Örebro, Sweden.

The 10-year net survival tended to decline with increasing age, and women had higher net and crude probabilities of dying of CD than men (, ).

Temporal trends of Crohn’s disease-specific survival

The ten-year net survival estimate was worse for patients diagnosed during 1963–1985 compared with patients diagnosed during 1986–1999 or 2000–2010 (, ), indicating that Crohn’s disease-specific survival improved over time.

Relative survival ratio and excess mortality

The overall survival of CD patients was almost equal to that in the general population during the first 10 years of follow-up [RSR = 0.98; 95% CI: (0.95–1.00)]. However, the survival of female patients aged ≥60 years at diagnosis was lower than expected, particularly during the first calendar period (1963–1985) ().

Table 3. Ten-year cumulative relative survival estimates among patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in Örebro county 1963 to 2010 by calendar periods of diagnosis for each combination of age and sex.

After adjusting for age, sex, disease location and behaviour, as well as years of follow-up, there is some evidence that patients diagnosed during 1986–1999 and 2000–2010 experienced 60% and 64% lower excess mortality respectively compared with patients diagnosed during 1963–1985 (). Older age, female sex, colonic localisation compared with ileal localisation, and stricturing/penetrating disease behaviour compared with inflammatory disease behaviour seemed to be associated with excess mortality. However, statistical significance was reached only for age at diagnosis. The estimated excess mortality rate for patients aged 60 years or above at diagnosis was 8.0 times higher than that of patients aged 40–59 years at diagnosis.

Table 4. Excess mortality ratios during the first 10 years after Crohn’s disease diagnosis stratified by calendar period of diagnosis, age group, sex, disease location and behaviour.

Discussion

In this population-based, regional cohort, we found that both overall and Crohn’s disease-specific survival was worse for patients diagnosed with CD during the earlier (1963–1985) calendar period than for patients diagnosed later. Crohn’s disease-specific survival declined with increasing age at diagnosis and was poorer for female patients. The 10-year overall survival of CD patients was largely similar to that in the general population but was reduced in older female patients, particularly in those diagnosed during the 1963–1985 calendar period. The multivariable-adjusted Poisson regression model suggested that earlier diagnostic period, older age, female sex, colonic location, and stricturing/penetrating disease behaviour may be associated with excess mortality, although statistical significance was reached only for older age.

Mortality has been examined in numerous studies of Crohn’s disease, but the findings regarding Crohn’s disease mortality are inconsistent in the existing literature [Citation19]. Inconsistent findings may in part be explained by methodological differences, differences in diagnostic criteria [Citation20], variations in degree of selection bias, and possible temporal changes in disease severity and survival.

The overall survival observed in our study population was comparable to that reported from similar population-based cohorts of CD patients [Citation2,Citation5,Citation7,Citation21]. We found that, compared with the 1963–1985 diagnostic period, disease-specific survival improved during the 1986–1999 and 2000–2010 calendar periods. The Swedish nationwide population-based cohort study also suggested that IBD-related deaths have declined over time [Citation11]. The early period is known for the extensive use of surgical resections [Citation22], and excess mortality early after diagnosis [Citation23]. Advances in medical and surgical therapies probably contributed to these findings [Citation24]. Changes in disease severity [Citation12] and diagnostic criteria [Citation20], as well as decreasing proportion of patients progressing to complications [Citation25] could all contribute to the improvement of disease-specific survival over time.

Some previous studies suggested lower [Citation1], while others found higher than expected [Citation2,Citation3] mortality rates in CD patients as compared with the general population. A study by Munkholm [Citation26] did not show excess mortality during the first 10 years after diagnosis. However, an excess mortality was noted over a longer follow-up time. In a study by Olen et al., Crohn’s disease patients diagnosed between 1964–2014 and identified from the national patient register using ICD codes had a higher mortality rate compared with the general population controls [Citation11]. While we confirmed all cases with Crohn’s disease by a review of medical records, some cases in the nationwide Swedish study may not have fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for Crohn’s disease since a previous validation study reported a positive predictive value of 97% when defining Crohn’s disease from ICD codes [Citation27]. Overall, the survival of CD patients in our study was similar to that in the general population during the first 10 years of follow-up, which could partly be due to a high proportion of patients diagnosed under the age of 60 years. Our further analysis; stratified by calendar period of diagnosis, age, and sex; suggested lower than expected survival for female patients aged ≥60 years at diagnosis, particularly if diagnosed during the 1963–1985 calendar period. Estimates from our multivariable-adjusted regression model also suggested that the earlier diagnostic period (1963–1985), older age at diagnosis, female sex, and potentially colonic location and stricturing/penetrating disease behaviour may be independently associated with disease-related excess mortality. Some previous studies have also linked female sex [Citation7,Citation28] and colonic disease at diagnosis [Citation7,Citation21] with poorer survival, while existing data on disease behaviour is more ambiguous. Some studies found that inflammatory disease behaviour was associated with increased mortality risks [Citation7], and that stricturing/penetrating disease was not associated with decreased survival [Citation29]. Others found no difference in disease behaviour between deceased CD patients and survivors [Citation8].

This study has several strengths but also some weaknesses. The strengths of this study include the use of prospectively collected data from medical records, which ensured the inclusion of all patients diagnosed with CD in the specified period and the availability of clinically relevant information. We followed patients using national registers, which enabled a virtually complete follow-up. We applied various measures of survival, which provided different but complementary information and thus a complete picture of CD survival in a given population. Since the cause of death can be misattributed in death certificates, we estimated CD-related survival using relative survival methodology, which does not depend on the cause of death information (the information on underlying cause of death was included only for descriptive purposes). Our study, however, was limited by the small number of patients. Small sample size may increase the impact of unmeasured confounding factors. Due to the low number of events in the predominantly young patient population, statistical power was limited for some analyses, and we could not formally assess statistical significance of possible interaction effects in the regression model. As CD patients are more often smokers compared to general population, the difference between all-cause mortality between CD patients and the general population could be inflated by deaths caused by smoking (cardiovascular disease, cancers, etc). Disease location and behaviour were assessed at diagnosis using medical notes, and changes over time were not taken into account, as this would create even more subgroups with fewer cases.

In conclusion, we found that Crohn’s disease-specific survival improved over time. Overall, the 10-year survival of patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease during 1963–2010 was almost equal to that of the comparable general population. However, older female patients, particularly women diagnosed in the 1963–1985 calendar period, had worse than expected survival. Earlier diagnostic period, older age, female sex, colonic disease, and complicated disease behaviour at diagnosis seemed to be associated with excess CD-related mortality in the multivariable-adjusted regression model.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Uppsala Regional Ethics Committee (2010/304 and 2010/304/1).

Authorship statement

Guarantor of the article

Yaroslava Zhulina.

Financial disclosures

Jonas Halfvarson served as speaker and/or advisory board member for AbbVie, Celgene, Celltrion, Dr. Falk Pharma and the Falk Foundation, Ferring, Hospira, Janssen, MEDA, Medivir, MSD, Olink Proteomics, Pfizer, Prometheus Laboratories, Sandoz/Novartis, Shire, Takeda, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tillotts Pharma, Vifor Pharma, UCB and received grant support from Janssen, MSD, and Takeda.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank David Anderson for language editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Probert CS, Jayanthi V, Wicks AC, et al. Mortality from Crohn's disease in Leicestershire, 1972-1989: an epidemiological community based study. Gut. 1992;33(9):1226–1228.

- Ekbom A, Helmick CG, Zack M, et al. Survival and causes of death in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;103(3):954–960.

- Mayberry JF, Newcombe RG, Rhodes J. Mortality in Crohn's disease. Q J Med. 1980;49(193):63–68.

- Prior P, Gyde S, Cooke WT, et al. Mortality in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1981;80(2):307–312.

- Loftus EV, Jr., Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, et al. Crohn's disease in Olmsted county, Minnesota, 1940-1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(6):1161–1168.

- Farrokhyar F, Swarbrick ET, Grace RH, et al. Low mortality in ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease in three regional centers in England. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(2):501–507.

- Wolters FL, Russel MG, Sijbrandij J, European Collaborative study group on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD), et al. Crohn's disease: increased mortality 10 years after diagnosis in a Europe-wide population based cohort. Gut. 2006;55(4):510–518.

- Romberg-Camps M, Kuiper E, Schouten L, et al. Mortality in inflammatory bowel disease in The Netherlands 1991-2002: results of a population-based study: the IBD South-Limburg cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16(8):1397–1410.

- Jess T, Loftus EV, Jr., Harmsen WS, et al. Survival and cause specific mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a long term outcome study in Olmsted county, Minnesota, 1940-2004. Gut. 2006;55(9):1248–1254.

- Hovde Ø, Kempski-Monstad I, Småstuen MC, et al. Mortality and causes of death in Crohn's disease: results from 20 years of follow-up in the IBSEN study. Gut. 2014;63(5):771–775.

- Olén O, Askling J, Sachs MC, et al. Mortality in adult-onset and elderly-onset IBD: a nationwide register-based cohort study 1964-2014. Gut. 2020;69(3):453–461.

- Zhulina Y, Udumyan R, Henriksson I, et al. Temporal trends in non-stricturing and non-penetrating behaviour at diagnosis of Crohn's disease in Orebro, Sweden: a population-based retrospective study. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8(12):1653–1660.

- Eriksson C, Cao Y, Rundquist S, et al. Changes in medical management and colectomy rates: a population-based cohort study on the epidemiology and natural history of ulcerative colitis in Orebro, Sweden, 1963-2010. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(8):748–757.

- Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a working party of the 2005 Montreal world congress of gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A:5A–36A.

- Brooke HL, Talbäck M, Hörnblad J, et al. The Swedish cause of death register. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(9):765–773.

- Pohar Perme M, Estève J, Rachet B. Analysing population-based cancer survival - settling the controversies. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):933.

- Dickman PW, Coviello E. Estimating and modeling relative survival. The Stata Journal. 2015;15(1):186–215.

- Dickman PW, Sloggett A, Hills M, et al. Regression models for relative survival. Stat Med. 2004;23(1):51–64.

- Bewtra M, Kaiser LM, TenHave T, et al. Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are associated with elevated standardized mortality ratios: a meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(3):599–613.

- Lockhart-Mummery HE, Morson BC. Crohn's disease (regional enteritis) of the large intestine and its distinction from ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1960;1:87–105.

- Hellers G. Crohn's disease in Stockholm county 1955-1974. A study of epidemiology, results of surgical treatment and long-term prognosis. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1979;490:1–84.

- Fazio VW, Aufses AH. Jr. Evolution of surgery for Crohn's disease: a century of progress. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42(8):979–988.

- Weterman IT, Biemond I, Peña AS. Mortality and causes of death in Crohn's disease. Review of 50 years' experience in Leiden university hospital. Gut. 1990;31(12):1387–1390.

- Gustavsson A, Magnuson A, Blomberg B, et al. Endoscopic dilation is an efficacious and safe treatment of intestinal strictures in crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(2):151–158.

- Zhulina Y, Udumyan R, Tysk C, et al. The changing face of Crohn's disease: a population-based study of the natural history of Crohn's disease in Orebro, Sweden 1963-2005. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(3):304–313.

- Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, et al. Intestinal cancer risk and mortality in patients with crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1993;105(6):1716–1723.

- Shrestha S, Olén O, Eriksson C, SWIBREG Study Group, et al. The use of ICD codes to identify IBD subtypes and phenotypes of the Montreal classification in the Swedish national patient register. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(4):430–435.

- De Dombal FT, Burton IL, Clamp SE, et al. Short-term course and prognosis of Crohn's disease. Gut. 1974;15(6):435–443.

- Selinger CP, Andrews J, Dent OF, et al. Cause-specific mortality and 30-year relative survival of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(9):1880–1888.