Abstract

Background

Gastrointestinal bleeding is a common clinical problem in patients using low-dose acetylsalicylic acid (ASA). It is uncertain whether aspirin should continue to be used in patients who develop acute gastrointestinal bleeding during low-dose ASA therapy.

Aims

To assess whether ASA should be continued in patients who develop GI bleeding during low-dose ASA.

Methods

All patients admitted to an academic hospital for acute gastrointestinal bleeding between 2009 and 2011 were reviewed retrospectively. Clinical characteristics, comorbidities, medications and treatments were recorded from the patient records. Patients were divided into two groups based on continuing or discontinuing ASA after discharge.

Results

A total of 548 patients were included. ASA was continued in 282 (51.5%) (ASAc group) and discontinued in 266 (48.5%) patients (ASAd group). ASAc patients had more often coronary artery disease (57.8% vs. 42.5%, p < .001) and peripheral artery disease (17.4% vs. 9.0%, p = .004) than ASAd patients, whereas no differences were found in other comorbidities. There was no difference in 30-day all-cause mortality between ASAd and ASAc groups. However, after adjustment for age, gender and comorbidities, one-year all-cause mortality was double in the ASAd group (hazard ratio 2.16, 95% confidence interval 1.39–3.35). ASAd and ASAc groups did not differ with respect to cardiovascular mortality (4.9% vs. 5.3%, p = .811, respectively) or re-bleeding (10.2% vs. 9.2%, p = .713, respectively).

Conclusion

Continuing low-dose ASA after gastrointestinal bleeding was associated with lower all-cause mortality during the first year without increasing the risk of re-bleeding.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is one of the most common gastroenterological emergencies [Citation1]. However, with modern diagnostics and therapies, the incidence of peptic ulcers is declining. In Finland, the annual incidence of all peptic ulcers has decreased from 121 per 100,000 person-years in 2000–2002 to 79 in 2006–2008 [Citation2]. Similar findings have been reported in other European countries [Citation3]. The incidence of peptic ulcer has declined, particularly with the use of proton pump inhibitors and eradication of Helicobacter pylori. However, peptic ulcer bleeding remains prevalent due to the increase in the elderly population and the use of antithrombotic medication [Citation4].

Oral antithrombotic therapy is widely used in various therapeutic and prophylactic indications [Citation5]. The main concern linked to these medications is the fear of bleeding complications, especially in elderly patients with several comorbidities [Citation4,Citation6–9]. Consequently, hospitalizations due to upper GI bleeding caused by aspirin (ASA) are on the rise [Citation1]. On the other hand, there is strong evidence that antiplatelet therapy is beneficial in patients with established cardiovascular disease such as coronary artery or cerebrovascular disease [Citation10]. In these patients, discontinuation of ASA has been associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events [Citation11]. Even though there is several novel antithrombotic medications available (such as clopidogrel, ticagrelor, low-dose anticoagulants and anti-inflammatory agents), aspirin is still widely used because of its low price. Thus, in patients using ASA as a secondary prevention, the benefits of antiplatelet activity often outweigh the risk of bleeding [Citation8,Citation9]. However, there is little evidence on the best management strategy in patients using ASA for secondary prevention and recovering from GI bleeding. These patients are at the highest risk of cardiovascular events as well as bleedings. There is some evidence that after GI bleeding, ASA therapy may increase the risk for recurrent bleedings, but reduce all-cause mortality [Citation12]. There is also some evidence that the risk of cardiovascular events increases when antithrombotics are discontinued after peptic ulcer bleeding [Citation13]. The aim of this study was to assess whether ASA should be continued in patients who develop GI bleeding during ASA therapy. The primary outcomes were 30-day, one-year all-cause mortality, one-year cardiovascular mortality and one-year re-bleedings.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 1644 patients aged ≥18 years undergoing urgent or emergency endoscopy for suspected acute GI bleeding between January 2009 and December 2011 were reviewed. This study is a sub-study of Finnish Gastrointestinal Bleeding (Fin-GIB) Study designed to assess treatments of patients with acute gastrointestinal bleedings (GIB). For this sub-study, only patients who were on low-dose ASA (100 mg/day) at the time of admission (n = 548) were included. The patients were divided into those who continued on low-dose ASA when discharged (ASAc group) and those whose ASA treatment was discontinued (ASAd group).

Data collection

Our institution is a tertiary academic hospital with a catchment population of c. 250,000. The hospital utilizes electronic patient records and electronic databases for endoscopic and surgical procedures. Patients were identified retrospectively from these databases. Patient records were used to collect data on clinical characteristic of the patients as well as data on medication on admission, blood products, laboratory values, endoscopy findings, endoscopic and surgical procedures, and other treatment during the hospital stay. We used standardized data collection protocol and an electronic case report form to obtain information on baseline characteristics and medication of the patients, as well as on treatments given during the hospitalization. The patients were followed from the hospital admission until death or to the end of 2012. Survival status and causes of death were retrieved from the National Center for Statistics Finland.

The study protocol was approved by the local institutional review board. Formal informed consent was not required because of the register-based nature of the study. The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical methods

For categorical variables, cross-tabulations were used to compare distributions, and the differences were tested by using the chi-square test (χ2). For continuous variables, the statistical significance in means was determined by ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey. The assumption of normality was assessed graphically and tested with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

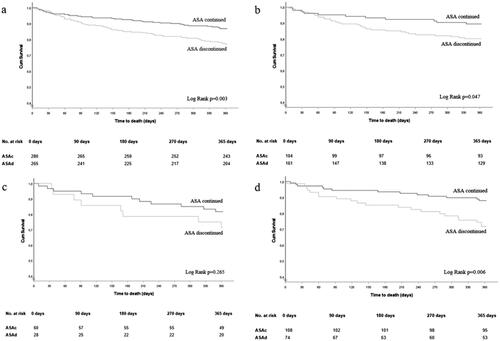

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to illustrate one-year survival (all-cause) between ASAc and ASAd-groups. The statistical significance between survival curves was assessed with the log-rank test. A univariable and multivariable analysis of predictors for all-cause mortality was performed using the Cox proportional hazard model, and the results are reported as crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Data management and analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows, version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 548 suspected GI bleeding patients on low-dose ASA were identified. ASA was discontinued in 266 patients (48.5%, ASAd group) and 282 patients continued to use ASA after discharge (51.5%, ASAc group). The mean age and gender distribution of ASAc and ASAd groups did not differ (). Patients in the ASAc group had more frequently a history of coronary artery disease (57.8% vs. 42.5%, p < .001) and peripheral artery disease (17.4% vs. 9.0%, p = .004) and were more often on clopidogrel than the ASAd patients (21.3% vs. 8.3%, p < .001). No significant differences in other comorbidities and medications were found.

Table 1. Demographics, comorbidities, medication and laboratory values at baseline.

Diagnosis and findings

Upper GI bleeding was more prevalent in the ASAd group (60.8% vs. 37.1%, p < .001), and therefore, more upper GI endoscopies were performed in this group (95.1% vs. 82.9%, p < .001) (). In contrast, there were more bleedings from the lower GI tract in the ASAc group (21.4% vs. 10.6%, p = .001), and thus, more colonoscopies were performed (41.1% vs. 24.5%, p < .001). One patient in the ASAc group underwent angioembolization. Emergency surgery was performed in two patients in the ASAc group and one patient in the ASAd group.

Table 2. Diagnostic procedures and findings.

An identifiable bleeding site was found in 61.4% of patients in the ASAc group and 72.1% of patients in the ASAd group (p = .008). ASAd group had more often bleeding from an ulcer in the stomach or duodenum (32.8% vs. 16.1%, p < .001), whereas the bleeding source was a benign tumor more often in the ASAc group (4.6% vs. 1.1%, p = .015). Most of the ulcers were classified into Forrest class 3 in both groups (). ASAc and ASAd groups did not differ with respect to Forrest classification.

Patients in the ASAd group needed more often transfusions of red blood cells (70.9% vs. 46.4%, p < .001), fresh frozen plasma (8.7% vs. 2.9%, p = .003) and thrombocytes (3.8% vs. 0.7%, p = .015) (). The nadir hemoglobin during the hospital stay was lower in the ASAd group (83 g/l vs. 91 g/l, p < .001). Active bleeding during endoscopy was more common in the ASAd group (19.2% vs. 8.3%, p < .001). The need for and the duration of treatment in the intensive care unit was similar in both groups ().

Table 3. In-hospital treatment.

Mortality and causes of death

The mean follow-up were 337 ± 84 days in the ASAc group and 316 ± 105 days in the ASAd group (p = .008). There was no significant difference in 30-day all-cause mortality between the ASAc and ASAd (3.2% vs. 1.9%, p = .331) groups (). However, at one-year, all-cause mortality was significantly higher in the ASAd group compared to the ASAc group (23.0% vs. 13.2%, p = .003, ). When adjusted for age, gender and comorbidities, all-cause mortality was two times higher in the ASAd group compared to the ASAc group (HR 2.16, 95% CI 1.39–3.35). Cardiovascular mortality in the ASAc and ASAd groups did not differ (5.3% vs. 4.9%, p = .811, respectively), whereas there were more deaths caused by infections (26.2% vs. 13.5%, p = .010) and GI causes (9.8% vs. 2.7%, p = .048) in the ASAd group. Continuing or discontinuing ASA had no effect on re-bleedings (9.2% vs. 10.2% in the ASAc and ASAd groups, p = .713).

Figure 1. All-cause survival in (a) all patients, patients with (b) upper GI tract, (c) lower GI tract and (d) unknown bleeding site and whose ASA treatment was continued or discontinued after GI bleeding.

Table 4. Mortality and causes of death during the follow-up.

In addition, we conducted a sub-group analysis for those with upper-GI bleedings (n = 265), lower-GI bleedings (n = 88) and unknown bleeding site (n = 182) (). Compared to the ASAd group, the one-year all-cause mortality was significantly lower in the ASAc group in patients with upper GI bleeding (10.6% vs. 19.9%, p = .045), unknown bleeding site (12.0% vs. 28.4%, p = .005) and there also was a trend in patients with lower GI bleeding (18.3% vs. 28.6%, p = .277).

In univariate analysis, discontinuation of ASA, age, paracetamol use, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, renal failure and malignancy were all predictors of one-year mortality (). After adjustments for these confounding factors, the difference in one-year all-cause mortality between the ASAd and the ASAc groups remained significant (Models 1–3, ).

Table 5. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis for all-cause mortality.

Discussion

The main findings of the study were that discontinuation of ASA after GI bleeding was associated with two-fold all-cause mortality compared to those continuing ASA. In addition, there was no difference between the groups with respect to recurrent bleedings during the one-year follow-up.

Several randomized studies have demonstrated the benefits of ASA for secondary prevention in patients with coronary artery disease or cerebrovascular disease in which plaque rupture and the following platelet activation and arterial occlusion play a major role [Citation7,Citation8,Citation10,Citation14]. In these patients, the benefits of ASA have outweighed the risks of bleeding associated with ASA [Citation6,Citation12]. On the contrary, due to increased risk of bleeding, low-dose ASA is not beneficial in primary prevention even in subjects with increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, such as the elderly, diabetes, and particularly, those with risk of bleeding [Citation5,Citation7–9,Citation15]. Following the increase in life-expectancy and high incidence of cardiovascular disease among the elderly, the consumption of low-dose ASA and other antithrombotic drugs has increased [Citation16]. In our study, all patients were on low dose ASA at the time of admission and underwent urgent or emergency endoscopy due to suspected GI bleeding. Thus, our patients represent the group with the highest risk of re-bleeding, and a careful evaluation of the risks and benefits of continuing versus discontinuing ASA is of the upmost importance.

Mortality

We found that all-cause mortality in patients who discontinued ASA therapy was more than two-fold higher when compared to those in whom ASA was continued, however, with no difference in the incidence of re-bleeding between the groups. In addition, the mortality benefit was seen both is patients with upper GI bleeding and in patients bleeding from unknown site. There was also a trend (albeit non-significant) favoring continuing ASA in patients with lower GI bleeding. Recently, a Swedish study reported that discontinuation of low-dose ASA in >600,000 patients using ASA for secondary prevention increased the risk of cardiovascular events by 46% [Citation14]. However, in that study, the reason for discontinuing ASA was not bleeding. Indeed, the impact of ASA discontinuation in patients surviving from first GI bleeding is poorly documented. Two registry-based studies have addressed the issue of the discontinuation antithrombotic therapy after GI bleeding. In the study by Siau et al. on 118 patients with upper GI bleeding, mortality during one-year follow-up was higher in the cohort not taking compared to those continuing on antithrombotic drugs (18% vs. 5%) [Citation17]. In contrast to us, in their study, the antithrombotic was not only ASA but included any antiplatelet agent as well as anticoagulants. In a subgroup of patients on ASA monotherapy, there was also a tendency towards better survival in those continuing ASA. Wang et al. evaluated 167 patients continuing or discontinuing antithrombotics after GI bleeding [Citation18]. Mortality and cardiovascular events were higher in patients discontinuing antithrombotic therapy. However, they did not report whether the antithrombotic therapy was ASA alone or whether other antithrombotics were included [Citation18]. In study by Derogar et al., 118 patients with peptic ulcer bleeding were on low-dose aspirin therapy on admission. The therapy was discontinued in 47 (40%). Patients who had their aspirin therapy discontinued had more than a six-fold increased risk of death or acute cardiovascular events within the first six months of follow-up [Citation19]. The closest counterpart to our study is the only placebo-controlled trial by Sung et al., in which 78 patients were randomized to ASA and 78 patients to a placebo, after GI bleeding [Citation12]. Mortality in the placebo group was significantly higher compared to those on ASA. However, the follow-up was relatively short, only eight weeks. Thus, any conclusions about long-term effects could not be addressed. The findings of our study are also in line with European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline recommendations, suggesting that patients with cardiovascular disease and who would benefit from aspirin should re-institute ASA soon after the bleeding is under control [Citation20,Citation21]. However, the guidelines recommendation is not based on data from large, randomized studies with long follow-up, but refers to the aforementioned study by Sung et al. [Citation11].

Bleeding

The benefits of resuming ASA must be evaluated against the risk of recurrent GI bleedings. In contrary to our expectations, the incidence of re-bleeding in our study was rather low (c. 10%) with no difference between patients on or off ASA. This is in contrast with earlier studies. In the study by Wang et al., re-bleeding risk in patients on antithrombotics was high (18.4%) and three-fold compared to patients discontinuing antithrombotics after GI bleeding [Citation18]. However, antithrombotic medication was not only ASA, but included any antiplatelet agents as well as their combinations. Secondly, they excluded patients who were prescribed proton pump inhibitors. In the studies by Siau et al. and Sung et al., the bleeding risk was also two to three-fold in patients on antithrombotics compared to those in whom it was discontinued [Citation12,Citation17].

Cause of death

In our study, cardiovascular mortality was the leading cause of death in the ASAc group. This finding is most probably not due to ASA continuing or discontinuing, but because the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases (coronary artery disease and peripheral artery disease) was high in the ASAc patients.

Mortality attributed to infections was the leading cause of death in the ASAd patients. Infection may trigger cardiovascular events (e.g. acute coronary syndrome or heart failure), particularly in the elderly, or a cardiovascular event may be complicated by infection (e.g. pneumonia). Therefore, it is often difficult to define the primary cause of death in these cases. This is also in accordance with the randomized study by Sung et al. [Citation22].

Contrary to our expectations, death due to GI disease was lower in the ASAc patients. This may be because of a selection bias since the patients were not randomized to ASAc and ASAd groups, but the selection was based on clinical judgement. On the other hand, our results are in line with Sung et al. In their study, mortality from a GI cause was three-fold in the placebo patients compared to those on ASA [Citation12]. However, although we admit that our study is the largest of its kind, it is still unpowered to address differences in the causes of death.

Limitations

An obvious limitation of our study was the retrospective nature of the study set-up, which does not allow characterization of the study population as accurately as a prospective trial. Nevertheless, the data in our study were collected from hospital registries and electronic patient records, in which the data were stored prospectively using standardized forms, with all information being available that was pertinent for this study. Another strength of this study was that in Finland, each patient has a national identification code which allows for easy follow-up and identification of the patients’ admissions and cause of death.

One source of bias in our study is that there were no information available to verify how well patients followed the instruction for the medication use after discharge. There is a possibility that some patients may have continued to use ASA without prescription, because this medicine is available as an over-the-counter medicine in Finland. On the other hand, there is also a possibility that some patients may have stopped using ASA by their own decision after the GI-bleeding episode.

Conclusions

Continuing low-dose ASA after GI bleeding was associated with lower one-year all-cause mortality independently of age, gender and comorbidities. Our study suggests that ASA can be continued without increasing the risk of re-bleeding. The results of this study should be confirmed in a randomized controlled trial.

Guarantor

Sami Miilunpohja.

Author contributions

SM, JJ, JMK, HK, MHe, HP, TR, JH have no personal interests to declare. All authors were designing the study and wrote the paper. SM and JJ analyzed the data and organized the collection of data. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Marja-Liisa Sutinen, RN, and medical students (Olli Pöntinen, Laura Ryhänen, Jukka Voutilainen, Sami Heikkinen, Jenna Ilmavirta, Anna Salminen, Johanna Weitz and Jenni Sipola) for their efforts in collecting data from hospital electronic databases. The authors thank Professor Emeritus Hannes Enlund, and Head of Assessment Vesa Kiviniemi in Finnish Medicines Agency for their help in planning the study concept and data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Thomopoulos KC, Vagenas KA, Vagianos CE, et al. Changes in aetiology and clinical outcome of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding during the last 15 years. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16(2):177–182.

- Malmi H, Kautiainen H, Virta LJ, et al. Incidence and complications of peptic ulcer disease requiring hospitalisation have markedly decreased in Finland. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(5):496–506.

- Hreinsson JP, Kalaitzakis E, Gudmundsson S, et al. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: incidence, etiology and outcomes in a population-based setting. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(4):439–447.

- Higuchi T, Iwakiri R, Hara M, et al. Low-dose aspirin and comorbidities are significantly related to bleeding peptic ulcers in elderly patients compared with nonelderly patients in Japan. Intern Med. 2014;53(5):367–373.

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(10):e177–e232.

- Burger W, Chemnitius JM, Kneissl GD, et al. Low-dose aspirin for secondary cardiovascular prevention – cardiovascular risks after its perioperative withdrawal versus bleeding risks with its continuation – review and meta-analysis. J Intern Med. 2005;257(5):399–414.

- McNeil JJ, Wolfe R, Woods RL, ASPREE Investigator Group, et al. Effect of aspirin on cardiovascular events and bleeding in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(16):1509–1518.

- McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, ASPREE Investigator Group, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(16):1519–1528.

- McNeil JJ, Woods RL, Nelson MR, ASPREE Investigator Group, et al. Effect of aspirin on disability-free survival in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(16):1499–1508.

- Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Antithrombotic Trialists' (ATT) Collaboration, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: Collaborative Meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1849–1860.

- Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspirin among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27(22):2667–2674.

- Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, et al. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic ulcer bleeding: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(1):1–9.

- Kim SY, Hyun JJ, Suh SJ, Jung SW, Jung YK, et al. Risk of vascular thrombotic events following discontinuation of antithrombotics after peptic ulcer bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(4):e40–e44.

- Sundstrom J, Hedberg J, Thuresson M, et al. Low-dose aspirin discontinuation and risk of cardiovascular events: a Swedish nationwide, population-based cohort study. Circulation. 2017;136(13):1183–1192.

- Zheng SL, Roddick AJ. Association of aspirin use for primary prevention with cardiovascular events and bleeding events: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2019;321(3):277–287.

- Luepker RV, Steffen LM, Duval S, et al. Population trends in aspirin use for cardiovascular disease prevention 1980–2009: the Minnesota heart survey. JAHA. 2015;4(12):e002320. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.115.002320.

- Siau K, Hannah JL, Hodson J, et al. Stopping antithrombotic therapy after acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding is associated with reduced survival. Postgrad Med J. 2018;94(1109):137–142.

- Wang XX, Dong B, Hong B, et al. Long-term prognosis in patients continuing taking antithrombotics after peptic ulcer bleeding. WJG. 2017;23(4):723–729.

- Derogar M, Sandblom G, Lundell L, et al. Discontinuation of low-dose aspirin therapy after peptic ulcer bleeding increases risk of death and acute cardiovascular events. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(1):38–42.

- Laine L, Jensen DM. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(3):345–360; quiz 361. 60; quiz 361.

- Gralnek IM, Stanley AJ, Morris AJ, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline – update 2021. Endoscopy. 2021;53(3):300–332.

- Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Ma TK, et al. Causes of mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a prospective cohort study of 10,428 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):84–89.