Abstract

Background and Aim

Few studies have evaluated risk factors for short-term re-bleeding in patients with colonic diverticular bleeding (CDB). We aimed to reveal risk factors for re-bleeding within a month in patients with CDB.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed clinical course of patients with CDB diagnosed at 10 institutions between 2015 and 2019. Risk factors for re-bleeding within a month were assessed by Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

Among 370 patients, 173 (47%) patients had been under the use of antithrombotic agents (ATs) and 34 (9%) experienced re-bleeding within a month. Multivariate analysis revealed that the use of ATs was an independent risk factor for re-bleeding within a month (HR 2.38, 95% CI 1.10–5.50, p = .028). Furthermore, use of multiple ATs and continuation of ATs were found to be independent risk factors for re-bleeding within a month (HR 3.88, 95% CI 1.49–10.00, p = .007 and HR 3.30, 95% CI 1.23–8.63, p = .019, respectively). Two of 370 patients, who discontinued ATs, developed thromboembolic event.

Conclusions

Use of ATs was an independent risk factor for short-term re-bleeding within a month in patients with CDB. This was especially the case for the use of multiple ATs and continuation of ATs. However, discontinuation of ATs may increase the thromboembolic events those patients.

Introduction

Colonic diverticulosis is found in 20% of Japanese people who undergo colonoscopy, and the incidence has been increasing in the aging of society [Citation1]. Colonic diverticular bleeding (CDB) is a common complication of colonic diverticulosis [Citation2], and it accounts for 30–65% of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) [Citation3]. Furthermore, it has been reported that CDB is a risk factor for severe LGIB [Citation4,Citation5].

Previous studies have indicated that use of antithrombotic agents (ATs) was a risk factor for onset [Citation6–10], severity [Citation11,Citation12] and re-bleeding in patients with CDB [Citation13–16]. In contrast, it is known that permanent discontinuation of ATs to prevent bleeding sometimes results in a fatal thromboembolism [Citation17–20]. In our previous study, the use of ATs was an independent risk factor for re-bleeding within a year in patients with CDB [Citation13]. However, only a few studies have identified risk factors for re-bleeding in the short term, and those prior reports analyzed small cohort of patients with CDB [Citation21,Citation22]. Moreover, the impacts of continuation and discontinuation of ATs on short-term re-bleeding within a month in patients with CDB remain unclear. We thus attempted a retrospective cohort study to identify risk factors for re-bleeding within a month in patients with CDB, with a reference to ATs.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a multicenter, retrospective cohort study for patients with CDB from 10 institutions in Iwate, Aomori and Akita prefectures in Japan. We enrolled patients admitted under a diagnosis of CDB during a period from January 2015 to August 2019. For patients who were hospitalized twice or more because of CDB, we analyzed the first hospitalization. The medical charts of the patients were reviewed to collect their clinical and demographic characteristics. We obtained informed consent from the subject patients via an opt-out system on a website. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Iwate Medical University (MH2019-135) and conducted according to the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Diagnosis of CDB

According to the Japanese guideline of Japan Gastroenterology Association (JGA) [Citation23], we defined CDB as the following; (1) sudden painless visible melena and active bleeding from colonic diverticula observed by colonoscopy and (2) sudden painless visible melena, colonic diverticula observed by colonoscopy, and exclusion of other lower intestinal bleeding diseases. Patients who did not undergo colonoscopy were excluded from the study. Re-bleeding was defined as visible melena at least 24 h after confirming clinical hemostasis.

Antithrombotic agents

In accordance with the guideline of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society (JGES) for the use of antithrombotic treatment in endoscopic intervention [Citation24], we classified ATs into antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants. Antiplatelet agents included aspirin, thienopyridine, cilostazol, eicosapentaenoic acid, sarpogrelate hydrochloride, dipyrudamole and prostaglandin E1 derivatives. Anticoagulants included warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants (DOAC), such as edoxaban, apixaban and rivaroxaban.

Decisions on the use of ATs during hospitalization and after discharge were made at the discretion of the attending physician. We defined ‘discontinuation of ATs’ as the discontinuation of any AT at the time of hospital admission. On some occasions, warfarin therapy was replaced by heparin. We regarded such cases as being under continuation of ATs.

Outcome measurements

We first evaluated risk factors for re-bleeding within a month after admission. Second, we investigated the relationship between ATs and re-bleeding during the equivalent period. We dichotomized the use of ATs according to the continuation or discontinuation and to the use of single or multiple ATs.

Statistical analysis

The relationship between re-bleeding within a month and each clinical factor was analyzed by univariate analysis with Cox proportional hazard models. The cutoff value for systolic arterial pressure was determined based on a previous report [Citation21]. Variables with a p value <.1 were analyzed by multivariate analysis with Cox proportional hazard models to identify independent risk factors associated with re-bleeding within a month. In the multivariate analysis, the hazard ratio (HR) was adjusted for age and sex. In each analysis, a p value <.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with JMP version 13 for Mac (Statistical Discovery Program, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient demographics

During the study period, 396 patients were hospitalized with a diagnosis of CDB. Twenty-six patients were excluded from the study, because they were not examined by colonoscopy. There were 370 patients with CDB enrolled in the analysis. summarizes the clinical characteristics of the study population. The median age was 76 years, and there were more men (n = 219) than women (n = 151). The median duration of hospital stay was 8 days. One hundred and thirty-nine patients were treated by blood transfusion and hemostatic treatment was applied to 102 patients. One hundred and seventy-three patients had been taking ATs; 131 patients were taking single ATs and 42 were taking multiple ATs. One hundred and twenty-nine patients discontinued ATs after admission, while 44 patients continued the medication after admission.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients and details of antithrombotic agents.

Clinical course

Among 370 patients, 34 experienced re-bleeding within a month, and 82 experienced re-bleeding within a year. Two patients developed thromboembolic events during hospitalization. In both patients, the event occurred after interrupting AT. A patient dies of brain infarction and the other experienced myocardial infarction, who recovered uneventfully. No patient died of CDB.

Risk factors associated with re-bleeding

Results of univariate analyses for the risk of re-bleeding within a month are summarized in . Significant differences in the re-bleeding were observed with the use of ATs (p = .012). Also, single or multiple use of ATs (p = .012), and continuation or discontinuation of ATs (p = .026) were found to be risk factors associated with the re-bleeding.

Table 2. Univariate analysis for risk factors for re-bleeding within a month.

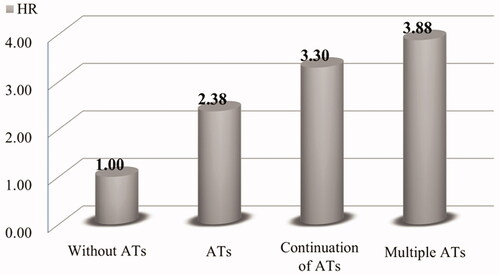

shows the results of the multivariate analysis for risk factors associated with re-bleeding within a month. We performed the multivariate analysis using three models according to the status of ATs use; Model 1 examined the effect of the use of ATs, Model 2 compared single AT and multiple ATs and Model 3 compared continuation and discontinuation of ATs. Model 1 showed that use of ATs was an independent risk factor for re-bleeding within a month (HR 2.38, 95% CI 1.10–5.50, p = .028). Models 2 and 3 showed that use of multiple ATs and continuation of ATs after admission were independent risk factors (HR 3.88, 95% CI 1.49–10.00, p = .007 for multiple ATs; HR 3.30, 95% CI 1.23–8.63, p = .019, for continuation of ATs). Hazard ratios of factors associated with the re-bleeding in each condition of ATs are indicated in .

Figure 1. Hazard ratios of re-bleeding within a month in each condition of ATs at admission compared with patients without ATs.

Table 3. Cox proportional hazards model of risk factors for re-bleeding within a month.

Discussion

In the present study, we searched for risk factors associated with short-term re-bleeding (within a month) among patients with CDB in a retrospective cohort of 10 institution in the northern part of Japan. As a consequence, we found that the use of ATs was an independent risk factor for the re-bleeding. We also found that the use of multiple ATs and continuation of ATs after admission were associated with a significantly higher risk of the re-bleeding. Even though ‘short-term’ re-bleeding has not been clearly defined for patients with CDB, approximately 50% of CDB patients, who rebled during subsequent follow up, experienced re-bleeding within a month in our previous study [Citation13]. We thus consider that short-term re-bleeding within a month is a significant clinical issue in CDB patients.

Most previous studies investigating risk factors for short-term re-bleeding in CDB enrolled a small cohort of study population. Recently, Nigam et al. [Citation25] reported that early colonoscopy for CDB did not reduce the risk of re-bleeding in a retrospective large cohort of a nationwide insurance claims database analysis. However, there have been no other multicenter studies focusing on short-term re-bleeding in CDB patients. It has also been reported in smaller retrospective studies that the alteration in hemodynamics at the time of hospital admission, early colonoscopy, need for blood transfusion and chronic kidney disease were factors associated with re-bleeding within 30–90 days in patients with CDB [Citation21,Citation22,Citation25]. In our study population, it has become evident that factors associated with the use of ATs were the significant items associated with short-term re-bleeding in patients with CDB.

In the international recommendations for patients with LGIB [Citation26,Citation27], it has been recommended that once-discontinued ATs against bleeding should be restarted as soon as possible. Similar recommendations have also been proposed in the guideline for CDB by the Japanese Gastroenterological Association (JGA) [Citation23]. Specifically, guidelines proposed by JGA state that ‘the risk of thromboembolism due to discontinuation of antithrombotic drugs and the risk of bleeding due to continuation varies among patients’. Although these guidelines include detailed statements for the treatment of ATs in patients with LGIB or those with CDB, there have been sparse evidence, which support the statements. Our present study could not provide statistical evidence for the risk of thromboembolism due to discontinuation of ATs. However, we found that continuing ATs and multiple ATs are associated with re-bleeding within a month.

In the present study, we showed that the risk of short-term re-bleeding in patients with CDB with the discontinuance of ATs was not significantly different from that in patients who continued ATs. In addition, two patients developed in thromboembolism after discontinuation of ATs, and one was fatal. On the other hand, no patient died from bleeding, and almost all patients were discharged from the hospital within a month. Previous studies reported that thromboembolism after discontinuation of ATs occurred within 2 weeks on average. It has been calculated that discontinuation of aspirin has a 3-fold increase in the risk of thromboembolism [Citation28], that discontinuation of DOAC has a more than 20-fold increase in the risk of thromboembolism [Citation29], and that cessation of warfarin has a risk of thromboembolism [Citation30–32]. Furthermore, gastrointestinal bleeding has been reported to be a risk factor for thromboembolism in itself [Citation20].

A recent report on LGIB indicated that most causes of hospital death in patients with LGIB did not suffer from severe bleeding, but underlying conditions and complications including thromboembolism during hospitalization were associated with the poor clinical course [Citation33]. Our results clearly indicated that patients taking ATs at the time of admission had a 2.38-fold increase in the risk of short-term re-bleeding. Moreover, even if they continued ATs after admission, the increase in the risk remained to 3.30-fold. Our results thus suggest that ATs should preferably be continued in patients with CBD to avoid potentially fatal thromboembolism.

Our study also clarified that the use of multiple ATs had a higher risk of short-term re-bleeding than the use of a single AT. A previous study of a retrospective analysis of patients with LGIB indicated that dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) was associated with a fivefold increase in the risk of re-bleeding [Citation34]. Another study reported that triple therapy with a combination of dual antiplatelet agents plus anticoagulants was associated with a higher mortality in patients with LGIB [Citation35]. As for overall gastrointestinal bleeding from various sources, antithrombotic therapy with variable combinations of multiple agents has been shown to be a significant risk factor of bleeding when compared to single-agent antithrombotic therapy [Citation36,Citation37]. Based on those observations, discontinuation of a single AT may be a choice for patients with uncontrollable CDB, who has been taking multiple ATs. This should be examined in a larger cohort.

Previous study indicated that endoscopic band legation more prevented re-bleeding than endoscopic clipping [Citation38]. However, our study could not reveal the usefulness of endoscopic hemostasis for re-bleeding. The reason for this may be that the number of patients who underwent endoscopic hemostasis was limited, and the effect of each treatment method on re-bleeding could not be examined. Further evaluation in a large prospective study is warranted to clarify this clinical question.

Several studies reported that NSAIDs had a risk of CDB [Citation9,Citation39], but the patients who took NSAIDs did not have higher re-bleeding rate in this study. We speculate that NSAIDs are associated with the development of CDB, but may have a limited impact on re-bleeding because they are more likely to be withdrawn after onset than ATs. A well-designed, multicenter prospective study is warranted to validate this speculation.

Our study has several limitations. First, the retrospective design seems to have introduced selection bias. For example, timings of colonoscopy and procedures for hemostasis were heterogeneous among the attending institutions. Second, there were not any predetermined principles regarding discontinuation, continuation and restart of ATs, which may have affected the risk of re-bleeding. Alternatively, it can be stated that our results are based on real world data in patients with CDB. Finally, the sample size was too small to evaluate the risk thromboembolic events and death. There were actually only two thromboembolic events among our study population. A large-scale, multicenter, prospective study is warranted to validate our findings.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that the use of ATs was an independent risk factor for re-bleeding within a month in patients with CDB. In addition, continuation of ATs during admission and use of multiple ATs were associated with a significantly higher risk of the re-bleeding. In consideration of actual cases of thromboembolism among our patients with discontinuance of ATs, our results suggest that early discontinuation of ATs should be avoided in patients with CDB.

Acknowledgments

The authors express the deepest appreciation to all of attending physicians and endoscopists who concerned this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The dataset generated during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Yamamichi N, Shimamoto T, Takahashi Y, et al. Trend and risk factors of diverticulosis in Japan: age, gender, and lifestyle/metabolic-related factors may cooperatively affect on the colorectal diverticula formation. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123688.

- Nagata N, Niikura R, Aoki T, et al. Increase in colonic diverticulosis and diverticular hemorrhage in an aging society: lessons from a 9-year colonoscopic study of 28192 patients in Japan. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:379–385.

- Gralnek IM, Neeman Z, Strate LL. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(11):1054–1063.

- Aoki T, Nagata N, Shimbo T, et al. Development and validation of a risk scoring system for severe acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(11):1562–1570.

- Xavier SA, Machado FJ, Magalhaes JT, et al. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: are STRATE and BLEED scores valid in clinical practice? Colorectal Dis. 2019;21:357–364.

- Strate LL, Liu YL, Huang ES, et al. Use of aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increases risk for diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(5):1427–1433.

- Yamada A, Sugimoto T, Kondo S, et al. Assessment of the risk factors for colonic diverticular hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(1):116–120.

- Taki M, Oshima T, Tozawa K, et al. Analysis of risk factors for colonic diverticular bleeding and recurrence. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(38):e8090.

- Yuhara H, Corley DA, Nakahara F, et al. Aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs increase risk of colonic diverticular bleeding: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49(6):992–1000.

- Nagata N, Niikura R, Aoki T, et al. Colonic diverticular hemorrhage associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, low-dose aspirin, antiplatelet drugs, and dual therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1786–1793.

- Joaquim N, Caldeira P, Antunes AG, et al. Risk factor of severity and recurrence of colonic diverticular bleeding. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2017;109(1):3–9.

- Nagata N, Niikura R, Aoki T, et al. Risk factors for adverse in-hospital outcomes in acute colonic diverticular hemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(37):10697–10703.

- Gonai T, Toya Y, Kawasaki K, et al. Clinical impact of antithrombotic therapy on colonic diverticular bleeding. DEN Open. 2022;2(1):e22.

- Vajravelu RK, Mamtani R, Scott FI, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and clinical effects of recurrent diverticular hemorrhage: a large cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1416–1427.

- Niikura R, Nagata N, Yamada A, et al. Recurrence of colonic diverticular bleeding and associated risk factors. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(3):302–305.

- Nishikawa H, Maruo T, Tsumura T, et al. Risk factors associated with recurrent hemorrhage after the initial improvement of colonic diverticular bleeding. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2013;76:20–24.

- Chan FK, Leung Ki EL, Wong GL, et al. Risk of bleeding recurrence and cardiovascular events with continued aspirin use after lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(2):271–277.

- Sengupta N, Feuerstein JD, Patwardhan VR, et al. The risks of thromboembolism vs. recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding after interruption of systemic anticoagulation in hospitalized inpatients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(2):328–335.

- Chai-Adisaksopha C, Hillis C, Monreal M, et al. Thromboembolic events, recurrent bleeding and mortality after resuming anticoagulant following gastrointestinal bleeding. A Meta-analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114(10):819–825.

- Nagata N, Sakurai T, Shimbo T, et al. Acute severe gastrointestinal tract bleeding is associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism and death. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(12):1882–1889.

- Fujino Y, Inoue Y, Onodera M, et al. Risk factors for early re-bleeding and associated hospitalization in patients with colonic diverticular bleeding. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(8):982–986.

- Kitagawa T, Katayama Y, Kobori I, et al. Predictors of 90-day colonic diverticular recurrent bleeding and readmission. Intern Med. 2019;58(16):2277–2282.

- Nagata N, Ishii N, Manabe N, et al. Guidelines for colonic diverticular bleeding and colonic diverticulitis: Japan gastroenterological association. Digestion. 2019;99(Suppl. 1):1–26.

- Fujimoto K, Fujishiro M, Kato M, et al. Guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment. Dig Endosc. 2014;26(1):1–14.

- Nigam N, Ham SA, Sengupta N. Early colonoscopy for diverticular bleeding does not reduce risk of postdischarge recurrent bleeding: a propensity score matching analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(6):1105–1111.

- Strate LL, Gralnek IM. ACG clinical guideline: management of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(4):459–474.

- Oakland K, Chadwick G, East JE, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut. 2019;68(5):776–789.

- Maulaz AB, Bezerra DC, Michel P, et al. Effect of discontinuing aspirin therapy on the risk of brain ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(8):1217–1220.

- Vene N, Mavri A, Gubensek M, et al. Risk of thromboembolic events in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation after dabigatran or rivaroxaban discontinuation – data from the ljubljana registry. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156943.

- Raunso J, Selmer C, Olesen JB, et al. Increased short-term risk of thrombo-embolism or death after interruption of warfarin treatment in patients with atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(15):1886–1892.

- Qureshi W, Mittal C, Patsias I, et al. Restarting anticoagulation and outcomes after major gastrointestinal bleeding in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(4):662–668.

- Nagata N, Sakurai T, Moriyasu S, et al. Impact of INR monitoring, reversal agent use, heparin bridging, and anticoagulant interruption on rebleeding and thromboembolism in acute gastrointestinal bleeding. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0183423.

- Oakland K, Guy R, Uberoi R, et al. Acute lower GI bleeding in the UK: patients characteristics, interventions and outcomes in the first nationwide audit. Gut. 2018;67:654–662.

- Oakland K, Desborough MJ, Murphy MF, et al. Rebleeding and mortality after lower gastrointestinal Bleeding in Patients Taking Antiplatelets or Anticoagulants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(7):1276–1284.

- Patel P, Nigam N, Sengupta N. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with coronary artery disease on antithrombotics and subsequent mortality risk. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33(6):1185–1191.

- Sorensen R, Hansen ML, Abildstrom SZ, et al. Risk of bleeding in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with different combinations of aspirin, clopidogrel, and vitamin K antagonists in Denmark: a retrospective analysis of nationwide registry data. Lancet. 2009;374(9706):1967–1974.

- Yasuda S, Kaikita K, Akao M, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1103–1113.

- Okamoto N, Tominaga N, Sakata Y, et al. Low rebleeding rate after endoscopic band ligation than endoscopic clipping of the same colonic diverticular hemorrhagic lesion: a historical multicenter trial in Saga, Japan. Intern Med. 2019;58(5):633–638.

- Tsuruoka N, Iwakiri R, Hara M, et al. NSAIDs are a significant risk factor for colonic diverticular hemorrhage in elder patients: evaluation by a case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(6):1047–1052.