Abstract

Background

Esophageal perforation is a rare and life-threatening condition with several treatment options. The aim was to assess the incidence, type of treatment and mortality of esophageal perforations in Sweden and to identify risk factors for 90-day mortality.

Method

All patients admitted with an esophageal perforation from 2007 to 2017 were identified from the National Patient Register. Mortality was assessed by linkage with the Cause of Death Registry. We analyze the incidence and the impact of age, sex, comorbidities on mortality.

Results

879 patients with esophageal perforation were identified, giving an incidence rate of 1.09 per 100,000 person-years. The median age at diagnosis was 68.8 years and 60% were men. The mortality was 26% at 90 days. Independent risk factors for death within 90 days were age (odds ratio (OR): 6.20; 95% (confidence interval) CI: 2.16–17.79 at 60–74 years and OR: 11.58; 95% CI: 4.04–33.15 at 75 years or older), peripheral vascular disease (OR: 2.92; 95% CI: 1.44–5.92) and underlying malignant disease (OR: 5.91; 95% CI: 3.86–9.03). In patients younger than 45 years, survival was lower among women than among men (at 5 years 73 and 93%, respectively). The cause of death among young women was often drug-related or suicide.

Conclusions

90-day mortality was 26%, old age, vascular disease and underlying malignant disease were risk factors.

Introduction

Esophageal perforation is a rare and life-threatening condition that affects 1–5/100,000 patients per year [Citation1–3]. Perforations are more common among men and the mean age is approximately 65 years [Citation3,Citation4]. The majority of perforations are iatrogenic and occur during endoscopic procedures such as dilatation or endoscopic resection [Citation1,Citation4]. Spontaneous perforation is often due to vomiting against resistance (Boerhaave’s syndrome). Less commonly, perforation may be caused by erosion of an esophageal foreign body, radiotherapy for esophageal cancer, esophageal ulcer, eosinophilic esophagitis, trauma or the ingestion of corrosive substances [Citation5,Citation6].

When the wall of the esophagus perforates, sepsis can occur due to non-sterile material entering the surrounding tissue. Iatrogenic perforation usually results in less contamination than spontaneous perforation because the patient has fasted for the procedure.

Many treatment options have been described for esophageal perforation. Diversion by means of a cervical esophagostomy prevents further contamination, but in modern practice, esophagostomy tends to be reserved for special circumstances (e.g., unstable patient, major disruption of the esophageal wall, severe contamination) due to the morbidity of the procedure [Citation7,Citation8]. Other approaches all try to achieve coverage or closure of the defect (endoluminal, transthoracic or transhiatal) coupled with drainage of any collection. Traditionally, open surgery was first-line, with primary repair ± local flap coverage as well as wide drainage. More recently, endoscopic deployment of a stent has been used as an alternative to cover the defect [Citation9]. In population-based studies from the United Kingdom [Citation10] and Finland [Citation3], it has been noted that more invasive surgical treatments have become less common. Other reports suggest that treatment with stents is becoming more common [Citation11] and in selected patients, the results obtained with stents are similar to more invasive methods [Citation7,Citation9,Citation12]. An alternative endoscopic strategy is negative pressure therapy (e.g., Esosponge®), which evacuates content from the defect and associated cavity with the aim of limiting the infection [Citation13]. Surgical drainage is generally required for contamination of the mediastinum or pleural space/s, while established abscesses and empyema can often be treated with radiological drainage.

Previously reported figures for 30-day mortality range from 10 to 30%, increasing to 22–39% at 90 days [Citation3,Citation10]. Five-year overall survival for esophageal perforation ranges from 54 to 69% [Citation2,Citation3]. Early diagnosis has been associated with decreased mortality. Previously reported risk factors associated with death within 90 days after perforation include age ≥70 years, presence of esophageal cancer or significant end-organ dysfunction (ischemic heart disease, congestive cardiac failure, or chronic liver or kidney disease) [Citation10].

Aim

The aims of this nationwide population-based cohort study are to assess the contemporary incidence and mortality of esophageal perforations in Sweden, to describe outcomes related to different treatments and to identify patient factors predisposing to death.

Methods

All patients over the age of 18 years with a diagnosis of esophageal perforation (ICD code K22.3) between the 1st of January 2007 and 31st of December 2017 were identified from the Swedish National Patient Register and included in the study. The date and cause of death were obtained by linkage with the Cause of Death Registry. Both of these registers are well described and have high validity [Citation14,Citation15]. Comorbidities present at the time of perforation were assessed from discharge diagnoses that were registered within 12 months before the perforation (Appendix A for all ICD codes). Treatment was defined as surgical if the patient had undergone surgical procedures such as thoracotomy, thoracoscopy, laparotomy or laparoscopy for the condition. Endoscopic treatment was defined as the use of therapeutic endoscopy such as stent placement. If neither surgery nor endoscopy was registered the treatment was labeled as best supportive care, which may include antibiotics and nil-by-mouth. The incidence of esophageal perforations was calculated from the annual disease rates and the respective population census of Sweden obtained from Statistics Sweden [Citation16].

The effect of patient factors on survival was analyzed using a logistic regression model calculating odds ratio (OR) with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) and survival was displayed using Kaplan–Meier plots. Possible patient factors affecting mortality as well as potential confounding factors were assessed, including age (categorized into ≤44 years, 45–59 years, 60–74 years and ≥75 years), sex (female/male) and comorbidities (hypertension (yes/no), ischemic heart disease (yes/no), congestive cardiac failure (yes/no), depression (yes/no), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (yes/no), alcohol abuse (yes/no), diabetes mellitus (yes/no), peripheral vascular disease (yes/no), chronic kidney disease (yes/no) and chronic liver disease (yes/no)).

Statistical analysis was done using STATA/IC 14.2 SE (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The study was approved by the local Regional Ethical Board of Linköping, Dnr 2019/00574.

Results

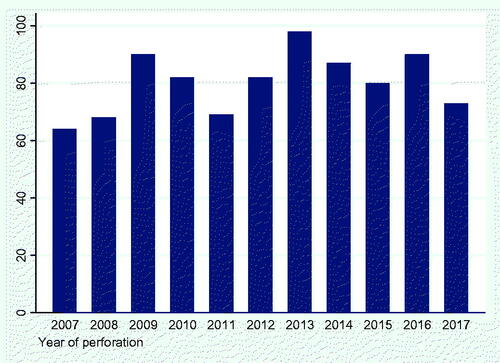

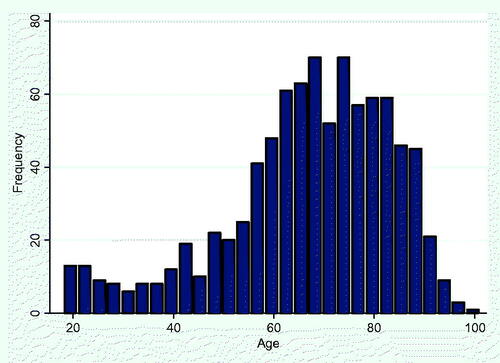

During the years 2007–2017, 879 patients were admitted to Swedish hospitals with the diagnosis ‘esophageal perforation’. The median age at diagnosis was 68.8 years and 59.9% of patients were men (). The incidence of esophageal perforation was 1.09 per 100,000 person-years and was higher among men (1.20 per 100,000 person-years) than among women (0.86 per 100,000 person-years). There was no change in incidence during the study period. The incidence for age is shown in . The most common comorbidities were hypertension (29%) and underlying malignant disease (15%) ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 879 patients diagnosed with esophageal perforation in Sweden between 2007 and 2017.

Best supportive care was provided to 38% of patients (). Endoscopic therapy only was performed on 34% of patients, 15% were treated surgically, and 12% of patients received a combination of surgical and endoscopic therapy for the perforation. The median number of in-patient admissions related to the perforation was 4 (range 1–12).

Table 2. Treatment characteristics of 879 patients diagnosed with esophageal perforation in Sweden between 2007 and 2017.

Comparing patients with malignant disease and those without, male sex was more common among patients with malignant disease (, p = .01). Patients with the malignant disease had more admissions than those without the malignant disease (p < .001).

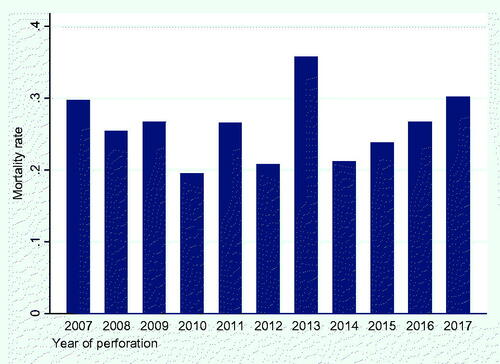

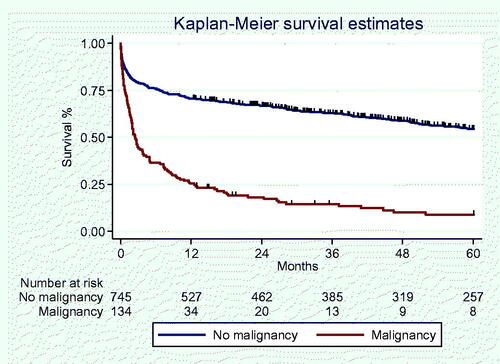

Thirty-day mortality was 17% and 90-day mortality was 26% (), with no significant change seen across the study period in either (). 5-year overall survival was 48%. Mortality was higher among patients with malignant disease. Resection was more common in patients with malignant disease than in patients without the malignant disease (19.4 vs. 5.1%, p < .001, ).

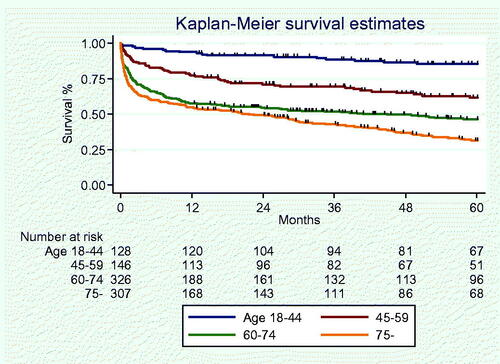

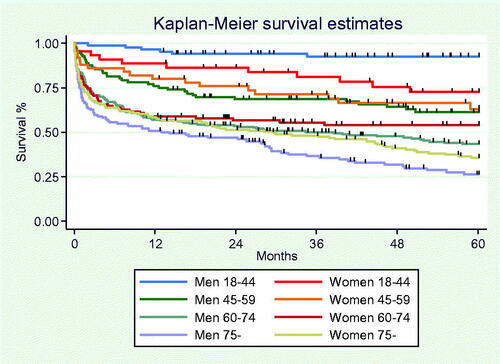

Old age was a significant risk factor for death within 90 days (age: 60–74; OR: 6.20; 95% CI: 2.16–17.79; ≥75 years OR: 11.62; 95% CI: 4.04–33.15) using age ≤44 years as reference. Comorbidities associated with increased mortality were; malignant disease (HR: 5.91; 95% CI: 3.86–9.03) and peripheral vascular disease (HR: 1.84; 95% CI: 1.13–3.00), as shown in . To illustrate the impact of age and underlying malignancy on survival, Kaplan–Meier survival curves are shown in and .

Table 3. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence limits (CI) from logistic regression for the outcome death from any cause within 90 days from diagnosis of perforation.

The combined impact of age and sex on survival is shown as a Kaplan–Meier survival curve in . Analysis showed that women under the age of 45 years had a worse outcome compared to men of the same age, with a 5-year survival of 73% compared with 93% for men (p = .005). We assessed the causes of death, which were more likely to be suicide, drug overdose and trauma among young women when compared with young men with esophageal perforation.

Discussion

The widespread utilization of therapeutic endoscopy has resulted in this modality becoming the commonest cause of esophageal perforation [Citation17]. Endoscopic management of endoscopic perforation is first-line [Citation8], although cervical perforations will usually respond to conservative care [Citation18]. Predictors of treatment failure using a stent are a very proximal or distal perforation (such that a seal could not be achieved) or a long injury (>6 cm) [Citation19]. Increased risk of complications (migration, dysphagia, hemorrhage, stent fracture) may be seen if a stent is left in place for more than 4 weeks [Citation20]. In that cohort, a 95% success rate was achieved with a stent and drain/s in 117 patients with benign intrathoracic perforation (excluding anastomotic leak), and using the above criteria the stent was removed at a mean of 19 days (range 7–51), with no patients required stent replacement. Surgery to address an endoscopic injury is generally reserved for circumstances where endoscopic treatment is not available, for injuries that are not likely to be controlled with endoscopic methods, if the injury is recognized late, or if endoscopic treatment has failed. Regardless of treatment modality, iatrogenic perforation seems to have quite good short- and long-term morbidity (including dysphagia at comparable levels to a reference population), but overall health-related quality of life is reduced even beyond 5 years [Citation21].

In esophageal perforation due to non-endoscopic causes, an attempt at non-operative management of non-endoscopic perforation can be considered under specific circumstances [Citation22]. There is an evolving role for classifications such as the Pittsburgh scoring system to predict morbidity, mortality and treatment strategy, including identifying patients eligible for non-operative management [Citation8,Citation12]. Therapeutic endoscopic procedures and percutaneous drainage remain important components of non-operative management. The evidence for non-operative management of non-endoscopic perforation remains sparse but clinical uptake is likely to continue to increase because of the perceived advantages over surgery. The gold standard for non-iatrogenic perforation arguably remains operative repair. In experienced centers, minimally-invasive techniques may be utilized safely [Citation23]. Whilst surgical treatment has been associated with lower survival compared with non-operative management in some non-randomized cohorts [Citation24], there are major potential confounders. For example, it is possible only the most severe presentations, or those who have failed non-operative management, are offered surgical treatment.

Surgical treatment was utilized in 20% of our cohort, which is similar to the 25% reported in a Danish study conducted between 1997 and 2005 [Citation4] but lower than a Finnish cohort [Citation3].

Esophageal perforation remains a rare condition in Scandinavian countries (0.31–0.95 per 100,000 person-years [Citation23]. In our cohort, men were more frequently affected, in keeping with other reports. For example, the aforementioned Finnish cohort had a median age of 65 with 62% men. They reported a 90-day mortality of 22%, which is similar to the 26% in the present study, while a meta-analysis of 75 studies on esophageal perforation (2971 patients) had a pooled mortality of 11.9% [Citation25]. This apparently low rate may be due to methodological issues; the other datasets were nationwide cohorts reporting overall mortality, rather than mixed national or sub-national datasets where only deaths attributed directly to esophageal perforation were included. The 5-year survival in the Finnish cohort was 54%, which is similar to our finding of 49%. In their cohort, early mortality was similar with benign and malignant causes while unsurprisingly, the malignancy had a worse prognosis at later time points. We also showed higher mortality when there was an underlying malignancy. In comparison, a study from the United Kingdom showed patients with esophageal cancer had inferior 30-day and 90-day survival, although strikingly, only 5.9% of patients in this cohort had an iatrogenic (endoscopic) etiology [Citation10].

In our cohort, the strongest predictor of mortality was age >75, with peripheral vascular disease also an independent predictor (as well as malignancy).

The inferior survival of esophageal perforation in young women compared with young men is a novel finding that prompted further investigation. It was not the esophageal perforation per se that caused the difference in survival between sexes but that these women have other factors that affect survival. We found indications that drug abuse or psychiatric disease leading to death through suicide, trauma or drug overdose was more common among young women with esophageal perforations. It is possible that the perforation may be related to drug abuse or self-harming behavior, for instance by ingesting foreign bodies.

There are several limitations to our study. The registry-based nature of the study meant it was not possible to determine the etiology of the perforation. Finally, as many as 17% of cases are not diagnosed until the autopsy and so the incidence in the present study may still be an underestimation [Citation2]. However, being a nationwide validated register allowed a large number of patients with well-defined clinical characteristics (i.e., patient risk factors) to be included for analysis.

In conclusion, esophageal perforation is rare but mortality is high. A spectrum of treatment options are available but randomised trials are needed to inform clinicians as to the best approach. Old age, underlying malignant disease and peripheral vascular disease predict an increased risk of dying. Young women appear to be a special subset of patients that warrant particular attention to co-existing psychiatric illness or substance abuse.

Author contributions

David Edholm devised the project. Roland E. Andersson and David Edholm performed the statistical analysis. David Edholm, Adam Frankel and Roland E. Andersson wrote the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Søreide JA, Konradsson A, Sandvik OM, et al. Esophageal perforation: clinical patterns and outcomes from a patient cohort of Western Norway. Dig Surg. 2012;29(6):494–502.

- Vidarsdottir H, Blondal S, Alfredsson H, et al. Oesophageal perforations in Iceland: a whole population study on incidence, aetiology and surgical outcome. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;58(8):476–480.

- Khan J, Laurikka J, Laukkarinen J, et al. The incidence and long-term outcomes of esophageal perforations in Finland between 1996 and 2017 - a national registry-based analysis of 1106 esophageal perforations showing high early and late mortality rates and better outcomes in patients treated at high-volume centers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(4):395–401.

- Ryom P, Ravn JB, Penninga L, et al. Aetiology, treatment and mortality after oesophageal perforation in Denmark. Dan Med Bull. 2011;58(5):A4267.

- Zwischenberger JB, Savage C, Bidani A. Surgical aspects of esophageal disease: perforation and caustic injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(8):1037–1040.

- Runge TM, Eluri S, Cotton CC, et al. Causes and outcomes of esophageal perforation in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(9):805–813.

- Abbas G, Schuchert MJ, Pettiford BL, et al. Contemporaneous management of esophageal perforation. Surgery. 2009;146(4):749–756.

- Chirica M, Kelly MD, Siboni S, et al. Esophageal emergencies: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:26.

- Freeman RK, Van Woerkom JM, Ascioti AJ. Esophageal stent placement for the treatment of iatrogenic intrathoracic esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(6):2003–2008.

- Markar SR, Mackenzie H, Wiggins T, et al. Management and outcomes of esophageal perforation: a national study of 2,564 patients in England. Official J Am Coll Gastroenterol. 2015;110(11):1559–1566.

- Thornblade LW, Cheng AM, Wood DE, et al. A nationwide rise in the use of stents for benign esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(1):227–233.

- Schweigert M, Santos Sousa H, Solymosi N, et al. Spotlight on esophageal perforation: a multinational study using the Pittsburgh Esophageal Perforation Severity Scoring System. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;151(4):1002–1011.

- Alakkari A, Sood R, Everett SM, et al. First UK experience of endoscopic vacuum therapy for the management of oesophageal perforations and postoperative leaks. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019;10(2):200–203.

- Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):450.

- Johansson LA, Westerling R. Comparing Swedish hospital discharge records with death certificates: implications for mortality statistics. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(3):495–502.

- Statistics Sweden. 2021 [cited 2022 Feb 1]. Available from: www.scb.se

- Lampridis S, Mitsos S, Hayward M, et al. The insidious presentation and challenging management of esophageal perforation following diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(5):2724–2734.

- Paspatis GA, Arvanitakis M, Dumonceau J-M, et al. Diagnosis and management of iatrogenic endoscopic perforations: European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) position Statement - Update 2020. Endoscopy. 2020;52(9):792–810.

- Freeman RK, Ascioti AJ, Giannini T, et al. Analysis of unsuccessful esophageal stent placements for esophageal perforation, fistula, or anastomotic leak. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(3):959–965.

- Freeman RK, Ascioti AJ, Dake M, et al. An assessment of the optimal time for removal of esophageal stents used in the treatment of an esophageal anastomotic leak or perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(2):422–428.

- Hauge T, Kleven OC, Johnson E, et al. Outcome after iatrogenic esophageal perforation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(2):140–144.

- Altorjay A, Kiss J, Vörös A, et al. A nonoperative management of esophageal perforations. Is it justified? Ann Surg. 1997;225(4):415–421.

- Elliott JA, Buckley L, Albagir M, et al. Minimally invasive surgical management of spontaneous esophageal perforation (Boerhaave’s syndrome). Surg Endosc. 2019;33(10):3494–3502.

- Zimmermann M, Hoffmann M, Jungbluth T, et al. Predictors of morbidity and mortality in esophageal perforation: retrospective study of 80 patients. Scand J Surg. 2017;106(2):126–132.

- Biancari F, D’Andrea V, Paone R, et al. Current treatment and outcome of esophageal perforations in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of 75 studies. World J Surg. 2013;37(5):1051–1059.

Appendix A

ICD codes

Comorbidities

Renal failure – N189

Cirrhosis – K70.3, K74.x, B18.2

Cardiac failure – I50.x

Ischemic heart disease – I20.x–I25.x

Hypertension – I10.x

Chronic obstructive lung disease – J44.x

Diabetes – E1x.x

Peripheral vascular disease – I7.x

Alcohol abuse – F10.x

Esophageal cancer – C15.x, C16.x

Cancer – Cxx

Lung cancer – C34.x

Treatments

Esophagostomy – JCB00

Esophageal resection – JCCxx

Thoracotomy – GAB10, GAB11

Thoracic drain – GAAxx

Stent – JCF12, JCF00

Surgery – JAH00, JAH01, JCB00, JCCxx, JDDxx, JCE00, JCE01, GAB10, GAB11, JCW96, JCW97, JCD00, JCD03, JCD10, JCD11, JCD96, JCD97, JCE40, JCE50, JCE96, and JCE97