Abstract

Background

Clinical guidelines on cytomegalovirus (CMV) colitis in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are hampered by the low quality of evidence. In this study, we aim to explore the attitude and management of CMV colitis in IBD among gastroenterologists.

Methods

A web-based survey was distributed to adult and pediatric gastroenterologists and trainees in academic and general hospitals in the Netherlands. The survey comprised data collection on respondents’ demographics, attitudes towards the importance of CMV infection in IBD on a visual analogue scale (from 0 to 100), and diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

Results

A total of 73/131 invited respondents from 32 hospitals completed the survey (response rate of 56%). The importance of CMV infection was scored at a median 74/100. Respondents indicated CMV testing as appropriate in the clinical setting of steroid-refractory colitis (69% of respondents), hospitalized patients with active colitis (64%), immunomodulator or biological refractory colitis (55%) and active colitis irrespective of medication use (14%). CMV diagnostics include histology of colonic biopsies (88% of respondents), tissue CMV PCR (43%), serum CMV PCR (60%), CMV serology (25%) and fecal CMV PCR (4%). 82% of respondents start antiviral therapy after a positive CMV test on colonic biopsies (histology or PCR).

Conclusions

Most Dutch gastroenterologists acknowledge the importance of CMV colitis in IBD. Strategies vary greatly with regard to the indication for testing and diagnostic method, as well as indication for the start of antiviral therapy. These findings underline the need for pragmatic clinical studies on different management strategies, in order to reduce practice variation and improve the quality of care.

The clinical significance of CMV-associated colitis in IBD remains a matter of debate

Recommendations regarding CMV colitis in current international guidelines are based on low to moderate evidence levels and different diagnostic strategies are proposed

Summary of the established knowledge on this subject:

We show that there is a high practice variation of diagnosis and management of CMV colitis in IBD amongst adult and pediatric gastroenterologists

This study underlined the need for pragmatic studies and guidelines on different management strategies including cut-off values to start therapy

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is associated with severe flares of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Especially in the challenging clinical settings of acute severe colitis and therapy refractory colitis, a diagnosis of CMV colitis should be considered. A higher prevalence of CMV infections and CMV disease has been reported in ulcerative colitis as compared to in Crohn’s disease [Citation1]. CMV infection is associated with resistance to immunosuppressive treatment, disease duration and severity, risk of colectomy (in both pediatric and adult patients) and therefore increased costs [Citation2–4]. In addition, the start of antiviral therapy after diagnosis is associated with an improved outcome in adult patients [Citation5]. The prevalence of CMV infection and CMV disease in IBD is unclear, mostly due to the variety of definitions and the variety of (use of) diagnostic tests [Citation1]. In addition, exposure to corticosteroids or thiopurines, but not anti-TNF agents, has been associated with an increased risk of CMV reactivation in IBD patients [Citation6]. In pediatric patients also, steroid resistance is associated with CMV infection [Citation4]. Despite these observations, the clinical significance of CMV-associated colitis in IBD remains a matter of debate. Hypotheses range from CMV as a non-pathogenic innocent bystander to CMV as an important disease-mediating factor perpetuating the disease process [Citation7–9]. The viral load is proposed to differentiate both situations but it remains unclear which diagnostic strategy is most accurate. A high viral load in PCR testing on blood (≥2000 copies DNA/ml) or mucosal biopsies (≥250 copies DNA/mg) and high inclusions in the mucosal biopsies (≥5 positive cells) are associated with steroid resistance and effectiveness of antiviral therapy [Citation8].

As a consequence of the above-mentioned uncertainties, many recommendations regarding CMV colitis in current international guidelines are based on low to moderate evidence levels. In addition, the recommendations on the indication and methods of diagnostic testing are different. Although practical algorithms for the diagnosis and treatment of CMV infection in IBD have been published in addition to the international guidelines [Citation7,Citation8], clinicians are often puzzled by the conflicting recommendations. The objective of this study was to assess the diagnostic and management strategies for CMV colitis in IBD patients among Dutch adult and pediatric gastroenterologists.

Materials and methods

Study design

This is a national survey study among an expert group of adult and pediatric gastroenterologists with an IBD focus in the Netherlands. The survey was sent to the members of the Initiative on Crohn’s and Colitis, the Dutch network of adult gastroenterologists with an IBD differentiation. The survey was also sent to the network of Dutch pediatric gastroenterologists and gastroenterology trainees with IBD differentiation as determined by the supervisor from each academic hospital. It was conducted between 8 April 2019 and 9 June 2019. A targeted email reminder was sent to non-responders. The online survey tool Limesurvey was used to conducting the survey.

Survey design

We created a survey containing 15 open and closed questions (Supplementary Appendix). The survey contained the following 5 topics: a) demographic data on the respondents including sex, age, clinical role, size and type of hospital, years of work experience, b) the general attitude towards CMV, which was tested on a visual analogue scale, ranging from ‘innocent bystander’ (0) to ‘aggravating factor which requires treatment’ (100), c) clinical settings to test for CMV d) diagnostic CMV tests, e) indication for and therapy of CMV infection. Respondents were questioned on their preferred diagnostic and therapeutic approach and were allowed to provide open answers if their preferred approach was not captured by the survey.

Study definitions

Work experience in the field of (pediatric) gastroenterology was split up into two groups: five years or less and more than five years of experience. The consensus was defined as agreement by at least 75% of the respondents.

Statistical analysis

We only included complete surveys in the statistical analysis. The data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25. Continuous variables were reported as median (IQR). Categorical variables were summarized as frequency and percentages. Analyses were performed using descriptive statistics.

The Independent Sample T-test was used to compare continuous variables between subgroups. Chi-square tests or Fisher Exact tests were used to compare categorical data. Statistical significance was defined as p ≤ .05 and all tests were two-sided.

Ethical considerations

No approval from research ethics committees was required to accomplish the goals of this study because the survey did not involve patient material and consent for using data was assumed by participating in the survey.

Results

Respondents profile

A total of 73/131 invited medical professionals completed the survey; the response rate was 56% (). Of the respondents, 38/73 answers were obtained in the first round and 35/73 after a targeted reminder. The median age of the respondents was 42 years (interquartile range 36–49). These specialists are affiliated with 32 different hospitals, and represent 45% of the total of 69 Dutch hospitals. The response rate was lower in non-academic doctors vs academic doctors (non-academic 48.7% vs academic 65.5%, p = .056). There was no difference in response rate between adult and pediatric gastroenterologists (adult 55.9%, pediatric 55.0%, p = .943). Non-respondents were older than respondents (mean age 47 vs. 43 years, p = .017). shows the demographics of the respondents.

Table 1. Details of the respondents.

General attitude towards CMV infection in IBD

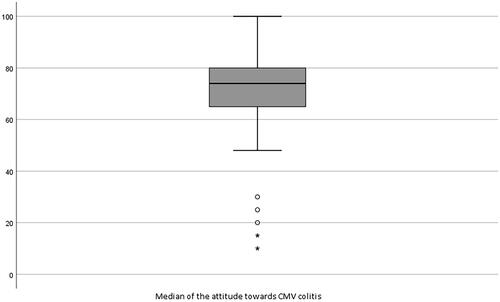

With regard to the general attitude towards CMV infection in IBD, the respondents scored a median of 74 (IQR 63–80) on a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 100 (). No significant differences were found when comparing medians between subgroups, academic versus non-academic (p = .561), shorter versus longer work experience (p = .215) and adult versus pediatric gastroenterologists (p = .422).

Figure 1. The general attitude towards the association of CMV infection in patients with IBD on a visual analogue scale, ranges from ‘innocent bystander’ (0) to ‘aggravating factor which requires treatment’ (100). 〇: mild outliers more than 1.5 times outside the IQR; ★: strong outliers more than 3 times outside the IQR.

Diagnosis

Respondents indicated testing for CMV appropriate in the clinical settings of severe exacerbations (64.4%), corticosteroid refractory exacerbations (68.5%), and immunomodulatory or biological refractory exacerbations (54.8%) (). Again, no significant differences were found between subgroups (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 2. Survey results: indication for diagnostic testing.

The diagnostic test options to detect CMV consisted of CMV serology, PCR testing on blood, feces or colonic biopsies and histopathology on colonic biopsies (haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and/or immunohistochemistry (IHC)) (). Significantly more respondents from academic hospitals reported the use of PCR on colonic biopsies (18/36 versus 9/37, p = .030). Adult gastroenterologists perform significantly more PCR tests on blood in comparison with pediatric gastroenterologists (41/62 versus 3/11, p = .021; Supplementary Table 1).

Table 3. Survey results: diagnostic tests for CMV colitis.

According to the respondents, endoscopic findings suggestive of CMV colitis were large punched-out ulcers (65.8%), multiple small ulcers (43.8%), small erosions (16.4%) and inflammatory polyps (4.1%). Fourteen respondents (19.2%) mentioned that no specific endoscopic findings are suggestive of CMV colitis.

Treatment

Indications to consider treatment with antiviral therapy according to the respondents were positive PCR testing on blood, colonic biopsies or feces (respectively 43.8%, 24.7% and 1.4% of the respondents) or a positive histopathologic result (74.0%). Eighty-two percent of the respondents consider treatment based on positive colonic biopsies (histopathology or PCR) (). Adult gastroenterologists (32/62 versus 0/11, p = .002) consider treatment more often after a positive PCR on blood compared to pediatric gastroenterologists (Supplementary Table 1).

Table 4. Survey results: indications to start treatment.

Thirty-seven respondents (54%) only consider treatment if the test reaches a certain threshold and 22 respondents (30%) only consider treatment based on a positive qualitative result. Thirty respondents (41%) perform two different tests. Of those, 23 respondents only need one of two tests to be positive before starting treatment, and seven respondents start treatment if both tests are positive. Only three respondents (4%) perform three tests and start treatment if two out of three tests are positive.

In the case of CMV colitis, 82% of the respondents treat patients with ganciclovir intravenous or valganciclovir oral based on the clinical condition of the patient and 15% always start treatment with ganciclovir intravenous and switch to valganciclovir oral depending on the clinical condition of the patient. Another respondent treats a patient orally or intravenously based on the viral load. No significant differences were seen between the subgroups.

Discussion

Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for CMV colitis in IBD patients remain a challenge. In this study, we observed a varying attitude among Dutch adult and pediatric gastroenterologists regarding the importance of CMV colitis in IBD patients. In addition, there is a lack of consensus regarding indications for testing, diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. This high practice variation raises concern for the under- and overuse of diagnostic testing and therapy for CMV-associated colitis in IBD and may be associated with an adversely affected disease course and/or higher costs [Citation3].

With regard to indications, a majority of respondents in our study use diagnostic testing for CMV in case of severe exacerbations requiring hospitalization and in patients with steroid and immunomodulator or biological therapy refractory disease. This approach is consistent with the literature and is recommended in most international guidelines [Citation10–13]. Nonetheless, agreement on the specific indications for CMV diagnostics is still below 75% in this study, and testing is performed less often than recommended in most guidelines. This practice variation may be caused by the dissimilar indications for testing that are recommended in available guidelines. These vary from testing CMV serology at baseline in every patient (ECCO), to moderate to severe, in particular steroid-refractory, active colitis (BSG), immunosuppressive treatment refractory colitis (ECCO), acute severe ulcerative colitis (ACG and ESPGHAN) and biologic resistant active Crohn’s disease (ACG) [Citation9,Citation10,Citation12–14].

In the recently updated version (2021) of the ECCO guideline on opportunistic infections, screening for CMV is recommended in all IBD patients at baseline and especially before starting immunosuppressive therapy [Citation10]. In this study (in which the survey was sent out before the publication of the updated version of the ECCO guideline), 65% of the respondents never or rarely test CMV serology at baseline in newly diagnosed patients. This strategy is not consistent with the ECCO recommendation. However, a study on 699 patients showed that latent CMV infection does not influence long-term disease outcomes in IBD and testing for CMV at baseline was therefore not recommended [Citation15].

The diagnostic method for endoscopic detection and assessment of colonic biopsies varies greatly among respondents. In this study, 65% of the respondents find punched-out ulcers more likely to be associated with CMV, whereas up to 19% of respondents find no specific findings suggestive of CMV colitis. According to the literature, the endoscopic images compatible with CMV colitis are various. Increased awareness may be triggered by findings of irregular ulcerations or wide mucosal defects and longitudinal ulcerations [Citation16,Citation17].

Most respondents (88%) use histopathology on colonic biopsies as a diagnostic method and acknowledge that H&E staining only is insufficient. IHC on colonic biopsies is considered the golden standard for diagnosing CMV colitis [Citation18]. Although several respondents choose this test, many respondents still do not know how their pathologist assesses the presence of CMV on biopsies and most respondents do not use a cut-off value as a diagnostic tool. PCR testing on colonic biopsies is performed by only 37% of respondents. However, a high viral load of PCR in tissue is associated with steroid resistance and response to antiviral therapy and it is suggested that less biopsies are needed for a diagnosis as compared to IHC [Citation19,Citation20]. Current guidelines do not specify a treatment cut-off value for the different recommended diagnostic tests, although patients with higher loads in both PCR and IHC on biopsies benefit more from antiviral therapy than patients with lower values [Citation7,Citation8]. Several cut-off values have been proposed, but we show in this study that clinicians are often unaware of these treatment strategies and therefore do not use them in clinical practice.

More than 60% of the respondents, 66% of adults and 27% of pediatric gastroenterologists perform a CMV PCR test on blood as a diagnostic test for CMV colitis. Although this test has a high specificity (87–100%) for CMV colitis, the sensitivity of this test is low (44–60%) when using H&E and/or IHC and PCR testing on biopsies as the reference standard even with a low cut-off level 250 copies/mL [Citation21,Citation22]. Based on these studies, the ECCO guideline recommends not relying on a blood-based test solely for a diagnosis of CMV colitis. Since most respondents choose only one diagnostic test for a diagnosis of CMV colitis, it is important for clinicians to acknowledge the low sensitivity of a blood PCR CMV test even with a low cut-off level [Citation8]. The limited use of a blood test by pediatric gastroenterologists is likely caused by a consensus paper in which 19 pediatric IBD experts agree that detection of CMV in the blood is not clinically meaningful in a child with acute severe ulcerative colitis [Citation23].

Only a few respondents use PCR testing on feces in patients with a suspicion of CMV colitis, despite several studies showing the high diagnostic value of this test using IHC and H&E staining on biopsies as a reference [Citation24,Citation25]. More studies are needed to add feces PCR to the arsenal of diagnostic tests for CMV colitis in IBD, but it could be a promising non-invasive alternative to other invasive test options.

Although this survey provides a good nationwide representation of clinical practice from IBD specialists working in various academic and non-academic hospitals, a few limitations need to be addressed. Potentially, non-responders to the survey, which were older and more often non-academic, find the subject of CMV colitis in IBD patients less relevant and therefore did not participate in this survey. This may have led to a non-response bias, resulting in a higher mean attitude towards CMV and respondents being more likely to choose diagnostic testing and treatment. However, a response rate of 56% is consistent with the mean response rate in survey studies by physicians and acceptable when taking non-response bias into account [Citation26]. Another possible limitation is that there may be a discrepancy between the answers from the respondents in the survey and real practice, due to a lack of knowledge amongst gastroenterologists on the practice of the pathologists and microbiologists in their hospitals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we show that variability in diagnosis and indication for treatment of CMV colitis is high. This lack of consensus raises concern about practice variation, which could lead to under- and over-treatment of a potentially severe complication in (pediatric) IBD patients. More strategic studies are needed to provide a more detailed recommendation for the diagnosis and treatment of CMV colitis in IBD patients in future guidelines, and may preferably include a combination of diagnostic tests including cut-off values to start therapy.

Author contributions

Conception and design of this report: RG, ACV. Statistical analysis: LB, RG. Drafting of the manuscript: RG, LB. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. All co-authors read, edited and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Supplemental material

Download MS Word (23.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all members of the Dutch Initiative on Crohn’s and Colitis (ICC) for their contribution to this study.

Disclosure statement

R.L. Goetgebuer, L. Bakker, A.A. van der Eijk: nothing to declare.

C.J. van der Woude: has served on advisory boards and/or received financial compensation from the following companies: Pfizer, MSD, FALK Benelux, Abbott laboratories, Janssen, Takeda and Ferring during the last 3 years.

A.C. de Vries: has participated in advisory board and/or received financial compensation from the following companies: Janssen, Takeda, Abbvie and Tramedico.

L. de Ridder: collaboration (such as involved in industry sponsored studies, investigator initiated study, consultancy, grant) with Celltrion, Abbvie, Ei Lilly, Takeda and Pfizer.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Römkens TEH, Bulte GJ, Nissen LHC, et al. Cytomegalovirus in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(3):1321–1330.

- Zhang WX, Ma CY, Zhang JG, et al. Effects of cytomegalovirus infection on the prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12(5):3287–3293.

- Hendler SA, Barber GE, Okafor PN, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with worse outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease hospitalizations nationwide. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35(5):897–903.

- Cohen S, Martinez-Vinson C, Aloi M, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in pediatric severe ulcerative Colitis-A multicenter study from the pediatric inflammatory bowel disease Porto group of the European Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018;37(3):197–201.

- Jones A, McCurdy JD, Loftus EV Jr, et al. Effects of antiviral therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease and a positive intestinal biopsy for cytomegalovirus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(5):949–955.

- Shukla T, Singh S, Tandon P, et al. Corticosteroids and thiopurines, but not tumor necrosis factor antagonists, are associated with cytomegalovirus reactivation in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51(5):394–401.

- Beswick L, Ye B, van Langenberg DR. Toward an algorithm for the diagnosis and management of CMV in patients with colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(12):2966–2976.

- Siegmund B. Cytomegalovirus infection associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(5):369–376.

- Lawlor G, Moss AC. Cytomegalovirus in inflammatory bowel disease: pathogen or innocent bystander? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16(9):1620–1627.

- Kucharzik T, Ellul P, Greuter T, et al. ECCO guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and management of infections in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(6):879–913.

- Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68(Suppl 3):s1–s106.

- Lichtenstein GR. New ACG guideline for the management of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;14(8):451.

- Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384–413.

- Turner D, Ruemmele FM, Orlanski-Meyer E, et al. Management of paediatric ulcerative colitis, part 2: acute severe colitis-an evidence-based consensus guideline from the European Crohn's and colitis organization and the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;67(2):292–310.

- van der Sloot KWJ, Voskuil MD, Visschedijk MC, et al. Latent cytomegalovirus infection does not influence long-term disease outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease, but is associated with later onset of disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(8):891–896.

- Suzuki H, Kato J, Kuriyama M, et al. Specific endoscopic features of ulcerative colitis complicated by cytomegalovirus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(10):1245–1251.

- Yang H, Zhou W, Lv H, et al. The association between CMV viremia or endoscopic features and histopathological characteristics of CMV colitis in patients with underlying ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Dis. 2017;23(5):814–821.

- Kandiel A, Lashner B. Cytomegalovirus colitis complicating inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(12):2857–2865.

- Roblin X, Pillet S, Oussalah A, et al. Cytomegalovirus load in inflamed intestinal tissue is predictive of resistance to immunosuppressive therapy in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(11):2001–2008.

- Pillet S, Williet N, Pouvaret A, et al. Distribution of cytomegalovirus DNA load in the inflamed colon of ulcerative colitis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(3):439–441.

- Kim JW, Boo SJ, Ye BD, et al. Clinical utility of cytomegalovirus antigenemia assay and blood cytomegalovirus DNA PCR for cytomegaloviral colitis patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. J Crohn's Colitis. 2014;8(7):693–701.

- Tandon P, James P, Cordeiro E, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of blood-based tests and histopathology for cytomegalovirus reactivation in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(4):551–560.

- Turner D, Travis SP, Griffiths AM, et al. Consensus for managing acute severe ulcerative colitis in children: a systematic review and joint statement from ECCO, ESPGHAN, and the Porto IBD working group of ESPGHAN. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(4):574–588.

- Herfarth HH, Long MD, Rubinas TC, et al. Evaluation of a non-invasive method to detect cytomegalovirus (CMV)-DNA in stool samples of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(4):1053–1058.

- Magdziak A, Szlak J, Mroz A, et al. A stool test in patients with active ulcerative colitis helps exclude cytomegalovirus disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(6):664–670.

- Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(10):1129–1136.