Abstract

Objectives

Liver transplantation (LT) is the only available cure for end-stage liver disease and one of the best treatment options for hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC). Patients with known alcohol-associated cirrhosis (AC) are routinely assessed for alcohol dependence or abuse before LT. Patients with other liver diseases than AC may consume alcohol both before and after LT. The aim of this study was to assess the effects of alcohol drinking before and after LT on patient and graft survival regardless of the etiology of liver disease.

Materials and Methods

Between April 2012 and December 2015, 200 LT-recipients were interviewed using the Lifetime Drinking History and the Addiction Severity Index questionnaire. Patients were categorized as having AC, n = 24, HCC and/or hepatitis C cirrhosis (HCV), n = 69 or other liver diseases, n = 107. Patients were monitored and interviewed by transplantation-independent staff for two years after LT with questions regarding their alcohol consumption. Patient and graft survival data were retrieved in October 2019.

Results

Patients with AC had an increased hazard ratio (HR) for death after LT (crude HR: 4.05, 95% CI: 1.07–15.33, p = 0.04) and for graft loss adjusted for age and gender (adjusted HR: 3.24, 95% CI 1.08–9.77, p = 0.04) compared to the other patients in the cohort. There was no significant effect of the volume of alcohol consumed before or after LT on graft loss or overall survival.

Conclusion

Patients transplanted for AC have a worse prognosis, but we found no correlation between alcohol consumed before or after LT and graft or patient survival.

Introduction

Liver transplantation (LT) is the only available cure for patients with end-stage liver disease, and a treatment option for severe acute liver failure and small hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) [Citation1]. In the Nordic Liver Transplant Registry (NLTR) the leading causes of LT are primary sclerosing cholangitis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and alcohol-associated cirrhosis (AC). These three diagnoses comprised almost 50% of all LTs in 2018 in Nordic countries. The 5-year survival rates were approximately 85% in patients with chronic liver disease and 70% in patients with HCC [Citation2].

Alcohol consumption after LT in patients with AC may have an impact on both graft and patient survival and a significant number of LT patients with AC will resume using alcohol after LT [Citation3–7]. All patients referred for LT undergo a thorough work-up including an examination to disclose substance use disorders and to select patients with an expected good adherence to lifelong medication and sobriety [Citation8,Citation9]. Despite the work-up, a significant number of patients with alcohol use disorder will not be detected [Citation10]. Some patients will continue to consume alcohol while on the waiting list for LT [Citation11,Citation12]. In Sweden, patients with a history of substance use disorder are referred for evaluation to an addiction specialist during evaluation for LT. They are interviewed about their history of alcohol, drug and other substance use, but the use of structured instruments varies between the two existing LT-centres in Sweden.

Drinking patterns and risk factors for alcohol relapse after LT are well studied in patients with alcohol-related liver disease and alcohol use disorders [Citation13–16], but data on drinking patterns in LT-recipients of non-alcohol-related liver diseases is limited [Citation13,Citation17].

The aim of this study was to assess the effects of alcohol drinking after LT on patient and graft survival taking background information such as biometrics, age, gender, socioeconomic factors and previous alcohol drinking into account regardless of the etiology of the liver disease.

Methods

The study was designed as a cohort study including 200 adult patients who underwent LT in Sweden at Karolinska University Hospital and at Sahlgrenska University Hospital between April 2012 and December 2015. Patients were included during hospitalization after LT up to three months after the operation. Exclusion criteria were a severe psychiatric disease, unresolved encephalopathy or inability to communicate in Swedish rendering interviewing impossible.

Trained research nurses performed the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) and Lifetime Drinking History (LDH) interviews within three months from LT. All answers referred to the period before LT. All nurses were certified to do the interviews after fulfilling a course approved by the Swedish National Board of Health.

The ASI is an interview used in patients with alcohol and/or drug use disorders. It contains questions regarding physical health, employment and financial support, alcohol and drug use, legal problems, drug use in the close family, family and social relations and psychiatric health. Participants rate the extent of problems in each area from 0 to 4, moderate to severe problems are defined as 2–4. The interviewer rates the severity of problems from 0 to 9, moderate to severe problems are defined as 4–9 [Citation17].

The LDH is a questionnaire regarding patients drinking history [Citation18–20]. It includes questions regarding the frequency and quantity of alcohol use from the first drink up to the time of the interview. Detailed information is obtained for the last year before LT. Information on quantity, frequency and binge drinking are obtained for fixed time intervals during the life-time. Binge drinking is defined as the intake of five or more standard drinks (12 g of ethanol) on one occasion for both women and men. We defined lifetime alcohol intake as the volume of all alcohol consumed (as standard drinks) during the lifetime of each patient. Lifetime binge intake was defined as the volume of alcohol drunk on occasions when the patients reported binge drinking.

Timeline follow-back was performed by the research nurses every third month for two years after LT. This procedure was carried out by phone calls, with patients recalling their drinks day-by-day for the last three months before the phone call, which was reported to the nurse.

We linked all our patients to the NLTR on October 8th, 2019 and retrieved the liver disease diagnoses, dates of LT, dates of re-LT and dates of death. We analysed patients with a diagnosis of HCC and/or HCV together since during the study period HCC was registered as the primary diagnosis even if the patient had more diagnoses, mostly HCV, and the prognosis for HCV during the study period was more or less equalized that for HCC. Outcome measures were patients’ hazard ratio for death defined as the time from LT to date of death and hazard ratio for graft loss defined as the time from LT to date of re-LT or death.

The study was approved by the regional ethical review board in Stockholm, (2009/1454-31/3 2010/1055-32 and 2012/367-32). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized with the median and interquartile range and categorical variables with numbers and percentages. Descriptive statistics were used to illustrate the baseline demographic, clinical and psychological characteristics of the study population. To investigate the differences between patients with AC, HCC and/or HCV and other diagnoses we used Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis (>2 groups) test for continuous variables. Hazard ratios for death were computed with univariable and multivariable Cox proportional-hazards models. The outcomes of our study were the hazard ratio for death calculated with mortality data from the LT date to death and the hazard ratio for graft loss calculated from the LT date to death or re-LT. To investigate the risk factors for outcome measures in the models we present crude hazard ratio (cHR) and adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) adjusted for age and gender as covariates. Hazard ratios (HRs) are presented with 95% confidence intervals and they are compared to all other patients in the cohort. Kaplan-Meier curves were plotted to graphically describe the survival of our population from their first LT, stratified by diagnoses, gender, alcohol consumption after LT and smoking. The comparison of the survival curves was computed with the log-rank test. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. (StataCorp. 2017. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC) was used to perform all analyses. All p-values were two-sided, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

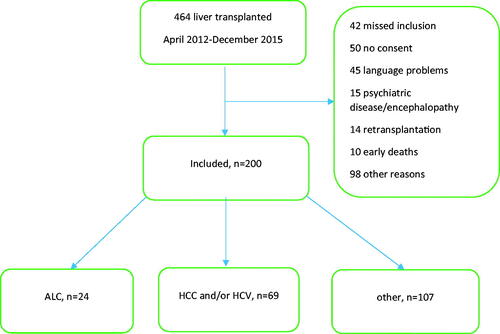

Two hundred patients were included and baseline characteristics are shown in . Forty-two patients were not asked to participate for logistic reasons, 50 patients did not give consent and language difficulties excluded 45 patients. There were 15 exclusions due to psychiatric diagnoses and encephalopathy which rendered interviewing impossible, 10 patients died early before inclusion could be done, 14 retransplanted were excluded erroneously and 98 were not included for other reasons.

Table 1(a). Patient characteristics: biometrics, diagnoses and smoking before liver transplantation.

There were 186 patients included who had their first LT whereas 14 were re-LT. The inclusion process has been reviewed in more detail previously, ten patients did not complete the interviews but were linked to the transplant register for follow-up as shown in [Citation21]. Twenty-four (12.0%) patients were transplanted with AC, 69 patients (34.5%) with HCC and/or HCV and there were 107 (47.5%) patients with other diagnoses. The most frequent other diagnosis was primary sclerosing cholangitis of whom there were 29 (14.5%) patients. Patients with other diagnoses were younger (p = 0.001) and more frequently women (p = 0.001) compared to patients with AC, HCC and/or HCV. More patients with AC smoked (43.5%) compared to the other groups (p = 0.006).

Figure 1. Flow chart. Legend: Flow chart of patient enrolment and classification by diagnosis. AC: alcohol-associated cirrhosis; HCV: hepatitis C induced liver cirrhosis; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma. "Other" comprised all other liver diseases except AC, HCV and HCC.

A majority of the patients and their interviewers were worried about their physical health according to the ASI interview, 15 (62.5%) of the patients with AC, 45 (63.8%) with either HCC and/or HCV and 75 (72.1%) of the patients with other diagnoses (p = 0.64). No significant differences were found in the ratings of problems by patients or interviewers regarding family or work-related issues, legal or psychiatric problems between the groups as shown in .

Table 1(b). Patient characteristics: socioeconomic, physical and psychiatric data before liver transplantation.

A history of cannabis and amphetamine use before LT was most frequent among patients with HCC and/or HCV (39.1%, p < 0.001) and consuming any alcohol during the last year before LT was most frequent among patients with other liver diseases (47.1%, p < 0.001). Patients with AC had the highest lifetime alcohol intake, 28 030 drinks (IQR: 6 986–89 676, p < 0.001) and they had the highest amount of alcohol drunk as binge drinking during their lifetime, 21 605 (IQR: 926–69 600, p < 0.001) as seen in .

Table 1(c). Patient characteristics: drug and alcohol use before liver transplantation.

Four patients with AC, eight patients with HCC and/or HCV and five patients with other liver diagnoses died during follow-up. Two AC patients, four HCC and/or HCV patients and six patients with other diagnoses were retransplanted. During the two-year follow-up after LT patients with AC had reported more alcohol consumed (120 drinks, SD: 0–208) and more binges, both in numbers of days (3 days, SD: 0–7, p = 0.017) and volume (19 drinks, SD: 0–163, p = 0.008) than the other two groups. In addition, there were few patients with AC who had abstained from alcohol during the follow-up (n = 6, 27.3%, p = 0.05), as shown in .

Table 2. Mortality, retransplantations and alcohol consumption the first two years after liver transplantation.

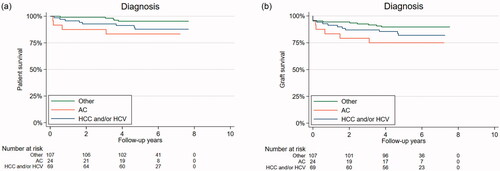

When comparing cHR for death after LT in AC patients with the other diagnoses, the cHR was significantly increased: 4.05, 95% CI: 1.07–15.33, p = 0.04). There was no increase in HRs for overall mortality in relation to lifetime alcohol consumption before LT, total alcohol consumed after LT, binge drinking or complete abstinence after LT even after adjusting for age and gender as shown in . When adjusted for age and gender a significant increase in HR for graft loss in patients with AC was seen (aHR: 3.24, 95% CI: 1.08–9.77, p = 0.04) as shown in .

Table 3. The hazard ratio for overall mortality.

Table 4. The hazard ratio for graft loss.

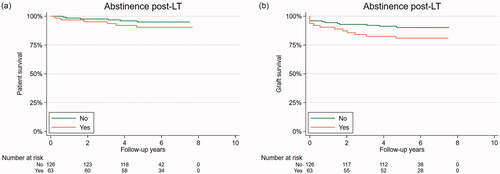

Patients with AC had a trend toward worse overall HR for mortality and graft loss as seen in Kaplan-Meier plots () (2a, log-rank test, p = 0.06 and p = 0.11 respectively) and there was a trend toward increased graft loss for those who reported drinking no alcohol after LT compared to the patients who did report alcohol consumption after LT but it did not reach significance ( and and ) (log-rank test, p = 0.23 and p = 0.07 respectively). In a sensitivity analysis drinking history, age, gender, smoking, alcohol consumed the last year and liver diagnoses before LT were included as covariates but the adjustments did not change any results.

Figure 2. (A) Overall survival is stratified by liver diagnoses. Legend: Overall survival stratified by liver diagnoses as a Kaplan-Meier plot during follow-up. Alcohol-associated cirrhosis, AC (orange), hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC, and/or hepatitis C, HCV (blue) and other diagnoses, Other (green). Log-rank test, p = 0.07. (b) Graft loss is stratified by liver diagnoses. Legend: Graft loss stratified by liver diagnoses as a Kaplan-Meier plot during follow-up. Alcohol-associated cirrhosis, AC (orange), hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC, and/or hepatitis C, HCV (blue) and other diagnoses, Other (green). Log-rank test p = 0.23.

Figure 3. (a) Overall survival stratified by alcohol consumption or no alcohol consumption after liver transplantation. Legend: Overall survival stratified by alcohol consumption after liver transplantation as a Kaplan-Meier plot during follow-up. Abstinence post-LT = yes (orange), any alcohol consumption post-LT = no (green). Log-rank test, p = 0.11. (b) Graft loss is stratified by alcohol consumption or no alcohol consumption after liver transplantation. Legend: Graft loss stratified by alcohol consumption after liver transplantation as a Kaplan-Meier plot during follow-up. Abstinence post-LT = yes (orange), any alcohol consumption post-LT = no (green). Log-rank test, p = 0.07.

Discussion

This study gives detailed information about patient mortality and graft loss for liver transplantation (LT) in relation to their alcohol intake before and after LT. It included patients with both alcohol and non-alcohol-related liver diseases. The most important findings are the increased hazard ratio for death among patients with AC and the lack of association between alcohol consumed before and after LT and survival in the whole cohort of patients.

The increased hazard ratio for death among patients with AC compared to patients with other chronic liver diseases is well in line with earlier studies on patients with liver diseases who did not undergo LT [Citation22]. Compared to transplanted patients with chronic liver diseases our patients’ impaired survival correlates well with overall results from the Nordic countries and Estonia. Patients with HCC have the worst prognosis in the Nordic Liver Transplant Registry [Citation2]. In a case-control study from Gothenburg, there were no differences in survival and graft loss between AC patients and their matched control after 10 years of follow-up, both groups having a 75% survival rate [Citation7]. In a study with data from European transplant centres 1-, 3-, 5-, and 10-years graft survival rates after LT in patients transplanted for alcohol-related liver diseases were 84%, 78%, 73%, and 58% which is comparable to our findings [Citation23]. Thus the prognosis for our patients is well in line with similar European patients.

The lack of association between mortality or graft loss and the amount of alcohol consumed before LT in the whole cohort is intriguing. It may seem contradictory to the poorer prognosis in patients with AC. However, it could be attributed to the fact that there are strict vetting procedures in place for patients with AC. Only patients with no recent reported alcohol consumption and a stable psychosocial background are registered on the waiting list. This is reflected in the patient characteristics: AC patients did not drink much the last year before LT and they did not differ significantly in the assessment of serious problems regarding work, legal, physical or psychological problems in the interviewer’s or the patients’ own assessments. In addition, many other aspects may influence the survival after LT that we did not control for, such as other comorbidities, medication, post-LT infections and another peri- and postoperative complications. Our AC patients were few but they drank more than HCC/HCV patients and patients with other liver diagnoses the first two years after LT. Hence, the vetting procedure selects patients with AC that have a fair prognosis after LT which may explain the lack of association between previous alcohol consumption and the prognosis after LT.

In our study there seemed to be a trend, albeit non-significant, towards an increased risk of graft loss for patients who abstained from alcohol after LT, as demonstrated in the Kaplan-Meier curve in . Previous studies have shown impaired survival in those with excessive alcohol consumption after LT irrespective of the underlying LT indication [Citation5]. A meta-analysis showed a three-fold increase in mortality risk for patients transplanted with AC (3.67: 95% CI: 1.42–9.50) at 10 years, but no difference after 5 years in a heterogeneous data set [Citation24]. These studies were performed in Japan, France, Spain and the US and alcohol use was only registered in the medical files or by self-reporting [Citation4–6,Citation25,Citation26]. None of the studies used a structured interview performed by someone not related to the direct follow-up of the patient and no one used timeline follow-back interviews. We suggest that the trend in our study should be interpreted with caution but it could be related to medication or complications after LT that we did not control for. In our opinion focus should be on the poorer prognosis for AC patients. Further studies should try to elucidate whether it is the post-LT alcohol consumption in AC or other factors that contribute to their poor prognosis.

The main strength of this study is the use of structured interviews, meticulous follow-up in combination with the use of a high-quality health register. Lifetime Drinking History gives extensive information about the frequency and quantity of alcohol intake during different periods of life. The ASI allows for a detailed description of the burden of dependence and socio-economical situation before LT and ASI have been validated in patients with dependence disorders both in the US and in Sweden [Citation27–29]. All interviews at inclusion and at follow-up were performed by nurses not involved in the clinical follow-up and the prognosis after LT correlates well with the prognosis seen in European data.

This study has some limitations. The patients’ information on alcohol consumption was not verified with blood or urine tests. The information about the patient's alcohol consumption is self-reported and could be underestimated. Most of the scores are to some degree subjective. We missed forty-two patients during 7 months at a screening at one center for logistic reasons. They did not differ in age, sex or primary diagnosis for their LT compared to the included patients. A separate analysis between the two participating centers of the different variables on alcohol consumption did not show any difference (data not shown). Another limitation is the use of registry data for diagnoses. We retrieved only the primary diagnosis from NLTR but some patients may receive only one diagnosis when they in fact have two or more liver diseases as the indication for the LT. This may especially be the case when HCC or HCV is the primary diagnosis for LT. Alcohol use as the main etiological agent causing liver disease may have been missed in some of the patients with HCV or HCC as harmful alcohol use is known to be associated with both [Citation30,Citation31].

In conclusion, this study shows that patients with AC have a worse prognosis after LT compared to other chronic liver diseases. AC patients used less alcohol the year before LT but significantly more the first two years after LT compared to the other patients after LT. We could not find a negative impact on either overall survival or graft survival of alcohol consumed before or during two years after LT. We recommend a continuous focus on the overall health of patients with AC and that the recommendation for abstinence still should remain an important part of the continuous care for all LT patients despite the negative findings in our study.

Author contributions

Study design: KS, AS, MC. Data collection: KS, MC. Data analysis: KS, AS, MIK, MB. Drafting manuscript: KS, AS, MC. Revising manuscript: all.

| Abbreviations | ||

| ASI | = | Addiction Severity Index |

| aHR | = | Adjusted hazard ratio |

| AC | = | Alcohol-associated cirrhosis |

| AIH | = | Autoimmune hepatitis |

| cHR | = | Crude hazard ratio |

| HCV | = | Hepatitis C cirrhosis |

| HCC | = | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| LDH | = | Lifetime Drinking History |

| LT | = | Liver transplantation |

| MELD | = | Model of end-stage liver disease |

| NLTR | = | Nordic Liver Transplant Registry |

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients for their participation. We also want to thank the research staff at Karolinska and Sahlgrenska University Hospitals: Micaela Viss, Rebecka Broman, Bianca Billing-Werner, Camilla Palmgren, Cickie Holmén (Stockholm), Marita Rosenberg, Ingela Broman and Christina Wibeck (Göteborg) for their commitment in interviewing and documenting. We are grateful for Espen Melum’s contribution at Scandiatransplant for providing data from the Nordic Liver Transplant Registry (NLTR), for professor Rolf Hultcrantz invaluable support and for the support from the Nordic Liver Transplantation Group (NLTG).

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adam R, Vincent K, Delvart V, et al. Evolution of indications and results of liver transplantation in Europe. A report from the european liver transplant registry (ELTR). J Hepatol. 2012;57(3):675–688.

- Mehlum E. The Nordic Liver Transplant Registry (NLTR) Annual report 2018. Available from: http://www.scandiatransplant.org/members/nltr/TheNordicLiverTransplantRegistryANNUALREPORT2018.pdf2018.

- Russ KB, Chen NW, Kamath PS, et al. Alcohol use after liver transplantation is independent of liver disease etiology. Alcohol Alcohol. 2016;51(6):698–701.

- Cuadrado A, Emilio F, Casafont F, et al. Alcohol recidivism impairs long-term patient survival after orthotopic liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Liver Transpl. 2005;11(4):420–426.

- Faure S, Herrero A, Jung B, et al. Excessive alcohol consumption after liver transplantation impacts on long-term survival, whatever the primary indication. J Hepatol. 2012;57(2):306–312. Aug

- Pageaux G-P, Michael B, Perney P, et al. Alcohol relapse after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease: does it matter? J Hepatol. 2003;38(5):629–634.

- Lindenger C, Castedal M, Schult A, et al. Long-term survival and predictors of relapse and survival after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(12):1553–1561.

- EASL clinical practice guidelines: liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2016;64(2):433–484.

- Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, et al. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the study of liver diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1144–1165.

- Day E, Best D, Sweeting R, et al. Detecting lifetime alcohol problems in individuals referred for liver transplantation for nonalcoholic liver failure. Liver Transpl. 2008;14(11):1609–1613.

- Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Hafeezullah M, et al. Failure to fully disclose during pretransplant psychological evaluation in alcoholic liver disease: a driving under the influence corroboration study. Liver Transpl. 2008;14(11):1632–1636.

- Carbonneau M, Bain AJ, Kelly VG, et al. Alcohol use while on the liver transplant waiting list: a single-center experience. Liver Transpl. 2010;16(1):91–97.

- Stokkeland K, Hilm G, Spak F, et al. Different drinking patterns for women and men with alcohol dependence with and without alcoholic cirrhosis. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;43(1):39–45.

- DiMartini A, Crone C, Dew MA. Alcohol and substance use in liver transplant patients. Clin Liver Dis. 2011;15(4):727–751.

- Rustad JK, Stern TA, Prabhakar M, et al. Risk factors for alcohol relapse following orthotopic liver transplantation: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(1):21–35.

- Perney P, Michael B, Sigaud H, et al. Are preoperative patterns of alcohol consumption predictive of relapse after liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease? Transpl Int. 2005;18(11):1292–1297.

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients. The addiction severity index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;168(1):26–33.

- Koenig LB, Jacob T, Haber JR. Validity of the lifetime drinking history: a comparison of retrospective and prospective quantity-frequency measures. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(2):296–303.

- Skinner HA, Sheu WJ. Reliability of alcohol use indices. The lifetime drinking history and the MAST. J Stud Alcohol. 1982;43(11):1157–1170.

- Jacob T, Ann SR, Bargeil K, et al. Reliability of lifetime drinking history among alcohol dependent men. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20(3):333–337.

- Schult A, Stokkeland K, Ericzon BG, et al. Alcohol and drug use prior to liver transplantation: more common than expected in patients with non-alcoholic liver disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(9):1146–1154.

- Stokkeland K, Ebrahim F, Ekbom A. Increased risk of esophageal varices, liver cancer, and death in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(11):1993–1999.

- Burra P, Senzolo M, Adam R, et al. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease in Europe: a study from the ELTR (european liver transplant registry). Am J Transplant. 2010;10(1):138–148.

- Kodali S, Kaif M, Tariq R, et al. Alcohol relapse After liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis—impact on liver graft and patient survival: a meta-analysis. Alcohol Alcohol. 2018;53(2):166–172.

- Rice JP, Jens E, Agni R, et al. Abusive drinking after liver transplantation is associated with allograft loss and advanced allograft fibrosis. Liver Transpl. 2013;19(12):1377–1386.

- Egawa H, Katsuji N, Yamamoto M, et al. Risk factors for alcohol relapse after liver transplantation for alcoholic cirrhosis in Japan. Liver Transpl. 2014;20(3):298–310.

- McLellan AT, Metzger HK, Peters D, et al. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199–213.

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al. New data from the addiction severity index. Reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173(7):412–423.

- Nyström S, Andrén A, Zingmark D, et al. The reliability of the swedish version of the addiction severity index (ASI). J Substance Use. 2010;15(5):330–339.

- Ramadori P, Cubero FJ, Liedtke C, et al. Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma: adding fuel to the flame. Cancers. 2017;9(12):130.

- Younossi ZM, Zheng L, Stepanova M, et al. Moderate, excessive or heavy alcohol consumption: each is significantly associated with increased mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(7):703–709.