Abstract

Background

The gastrointestinal tract is the second most involved organ for graft-versus-host disease where involvement of the small intestine is present in 50% of the cases. Therefore, the use of a non-invasive investigation i.e., video capsule endoscopy (VCE) seems ideal in the diagnostic work-up, but this has never been systematically evaluated before.

Objective

The aim of this systematic review was to determine the efficacy and safety of VCE, in comparison with conventional endoscopy in patients who received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Method

Databases searched were PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, and Cochrane CENTRAL. All databases were searched from their inception date until June 17, 2022. The search identified 792 publications, of which 8 studies were included in our analysis comprising of 232 unique patients. Efficacy was calculated in comparison with the golden standard i.e., histology. Risk of bias assessment was performed using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 tool.

Results

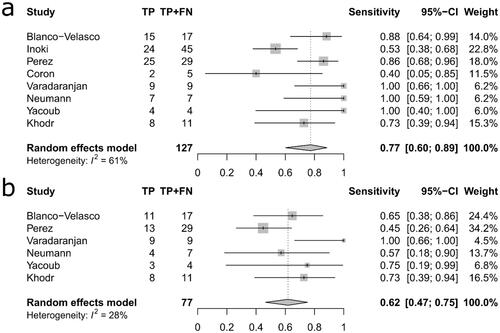

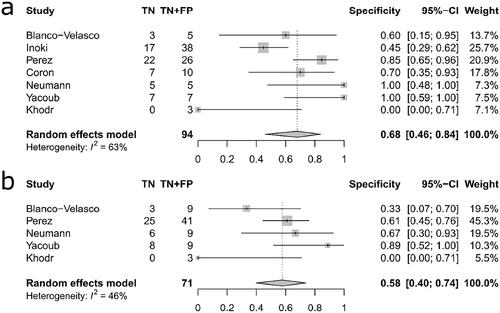

The pooled sensitivity was higher for VCE at 0.77 (95% CI: 0.60–0.89) compared to conventional endoscopy 0.62 (95% CI: 0.47–0.75) but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.155, Q = 2.02). Similarly, the pooled specificity was higher for VCE at 0.68 (95% CI: 0.46–0.84) than for conventional endoscopy at 0.58 (95% CI: 0.40–0.74) but not statistically significant (p = 0.457, Q = 0.55). Moreover, concern for adverse events such as intestinal obstruction or perforation was not justified since none of the capsules were retained in the small bowel and no perforations occurred in relation to VCE. A limitation to the study is the retrospective approach seen in 50% of the studies

Conclusion

The role of video capsule endoscopy in diagnosing or dismissing graft-versus-host disease is not yet established and requires further studies. However, the modality appears safe in this cohort.

Introduction

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) has, since its introduction in clinical practice two decades ago [Citation1], become the golden standard in diagnosing a broad range of small intestinal disorders where other diagnostic approaches have failed to provide a valid diagnosis [Citation2,Citation3]. Recent technical improvements, its increasingly affordable price and above all, its ability to visualize in detail the intestinal segments outside of the reach of traditional endoscopy has turned it into the investigation modality of choice for a growing list of small intestinal disorders [Citation4,Citation5]. In short, VCE is useful in diagnosing occult bleeding and small mucosal lesions (small bowel tumours, vascular malformations) that are otherwise not visible through standard imaging examinations [Citation6,Citation7]. At the same time, the list of contraindications has become shorter, and the only current absolute contraindication is gastrointestinal tract obstruction and known fibrotic strictures. Implantable cardiac devices (pacemakers, internal defibrillators, and left-ventricular assist devices), dysmotility or previous gastrointestinal surgery are no longer considered as absolute contraindications [Citation8,Citation9].

Application of VCE in the field of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is yet to be determined. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a well-established treatment modality for a variety of non-malignant and malignant hematologic disorders with an annual worldwide frequency of approximately 84 000 procedures and 1.5 million procedures performed by 2019 since 1957 [Citation10]. The absolute majority of the transplant recipients receive long term immunosuppressive medications as well as various drugs for transplant-related or other underlying causes. Many of these drugs are known to cause potential gastrointestinal adverse effects. Transplant recipients can also develop transplant-related gastrointestinal complications such as graft versus-host disease (GVHD) [Citation11]. GVHD is the most feared complication following HSCT with an incidence of 40% in matched related donors and 50% in matched unrelated donors. Moreover, the GI tract is the second most commonly involved organ for GVHD with small intestinal involvement in up to 50% of cases [Citation12–14]. The diagnosis of GVHD is based on a combination of symptoms, the exclusion of other causes, and the histologic picture due to the unavailability of a reliable biomarker. However, the optimal endoscopic approach is still under debate and some researchers argue that GI involvement is selective necessitating the need to obtain biopsies from specific sites [Citation15]. This strategy initially requires a better visualization of the entire GI tract prior to adopting an invasive procedure to procure tissue samples. A natural reluctance to employ this strategy would be the risk of exposing the patient for capsule retention and subsequent intestinal obstruction, which may have detrimental consequences in a compromised individual. Nevertheless, a compilation of published data on VCE in this patient population is yet to be done and the benefit and risks of this procedure remains unclear. The objective of this systematic review was therefore to determine the efficacy and safety of VCE, in comparison with conventional endoscopy in patients who received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The endoscopic findings were compared with the reference standard i.e., histology. This systematic review represents the first of its kind in this field and summarizes the current literature on the use of VCE following HSCT and attempts to merge the experience with this investigation in this specific patient population.

Methods

Search strategy

This systematic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines [Citation16]. The search strategy was reviewed for accuracy using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies criteria [Citation17] and the PRISMA extension for searching [Citation18].

The following criteria was stated for inclusion and exclusion of literature. Criteria for inclusion were original peer reviewed scientific papers describing capsule endoscopy after HSCT. Studies were excluded based on the following criteria: (I) non-available full texts, (II) non-peer reviewed publications, including theses, conference papers, abstracts, and book chapters, (III) non-original studies, such as systematic reviews and narrative reviews, (IV) studies with non-extractable data, (V) series less than three cases, (VI) studies with overlapping or duplicated data, (VII) studies in languages other than English.

In November 2021 a literature search was performed by the librarian author (EH) based on a search strategy developed in collaboration with two of the authors (JV, MO). The search strategy was focused on the two key concepts, i.e., capsule endoscopy and transplantation. The term ‘capsule endoscopy’ was searched with a combination of index-terms, free text-terms and well-established abbreviations. The term ‘transplantation’ was combined with ‘re-transplantation’ in an effort to include all relevant articles. Initially, a test search was conducted and evaluated before the final search strategy was applied in PubMed, and thereafter it was translated to three other databases.

Databases searched were PubMed (NLM), Scopus (Elsevier), EMBASE (Ovid), and Cochrane CENTRAL(Wiley) using a protocol designed as priori and registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022291026). All four databases were searched from their respective inception date until 18 November 2021. In June 2022, an update search was conducted covering records added to the databases until 17 June 2022. No restrictions were applied to years searched.

Study selection

The records from the databases were exported to Endnote and duplicates were removed. The remaining records were downloaded into the Rayyan web application for systematic reviews to facilitate the review process [Citation19]. Authors JV and MO screened all titles and abstracts independently to determine whether the studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Thereafter, eligibility assessment was performed i.e., full text reading and critical appraisal. This process was repeated for records that were retrieved in the updated search.

Quality assessment and risk of bias

Two authors (JV, MO) evaluated the risk of bias using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 (QUADAS-2) criteria [Citation20]. Disagreements on scoring were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers (J.V, M.O).

Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis was performed using the R programming language (version 4.1.3) [R Core Team] [Citation21]. The analysis was conducted by comparing macroscopic findings from the video capsule endoscopy or conventional endoscopy with histology, and a positive diagnosis was established if graft-versus host disease was detected on the biopsies or if the diagnosis were made on clinical grounds. The coupled forest plots of sensitivity, specificity, confidence interval (calculated according to Clopper Pearson) as well as assessing publication bias was done using the ‘meta’ R-package version 5.2–0. Due to the low number of studies the sensitivity and specificity were handled separately instead of using a bi-variate model. The heterogeneity was expected to be larger when summarizing diagnostic text accuracy due to thresholding effects [Citation22]. To compensate for the expected heterogeneity, we used a random effects model to summarize the results. Publication bias in the VCE estimates was assessed using Deeks’ test which has been recommended for meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy [Citation23,Citation24]. We used the implementation of Deeks’ test from the ‘meta’ R-package (function metabin, summary using diagnostic odds ratio, and a continuity correction of 0.5 to include all eight studies). Ideally, a minimum of 10 studies are required to reliably assess publication bias based on effect sizes, thus we cannot reliably exclude publication bias among our selected studies. As there were fewer studies for conventional endoscopy no assessment of publication bias was performed for this modality.

Results

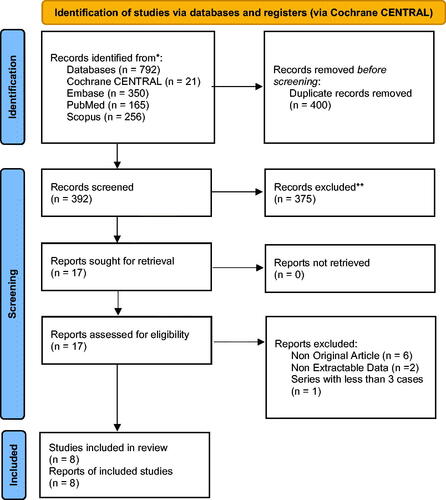

The search using the search algorithm identified 792 publications, of which 8 studies [Citation25–32] were selected for inclusion in our analysis (‘’). Four-hundred publications were excluded due to duplication, and another 384 were excluded after title and abstract review (irrelevant research studies, reviews, reports on 3 or less cases), leaving 8 publications for analysis. The eight publications comprised of 232 unique patients subjected to a total of 289 VCE procedures (‘’). In 75% (218/289) of these cases a conventional endoscopy with biopsy retrieval was also performed, and this procedure was considered as the reference standard test.

Figure 1. Shows the PRISMA flowchart of the study selection and inclusion process. *Consider, if feasible to do so, reporting the number of records identified from each database or register searched (rather than the total number across all databases/registers). **If automation tools were used, indicate how many records were excluded by a human and how many were excluded by automation tools.

Table 1. Study & population characteristics.

Bowel preparation

The use of bowel preparation prior to the examination with 1–2 liters polyethylene glycol solution was reported in four studies (96 patients/96 VCE), while no bowel preparation was administered in one study (94 patients/149 VCE). In the remaining three studies (42 patients/45 VCE), it was not stated whether or not bowel preparation was administered.

Diagnostic accuracy of VCE

The pooled sensitivity estimate was higher for VCE at 0.77 (95% CI: 0.60–0.89) compared to conventional endoscopy 0.62 (95% CI: 0.47–0.75) but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.155, Q = 2.02) (‘’). Similarly, the pooled specificity estimate was slightly higher for VCE at 0.68 (95% CI: 0.46–0.84) than for conventional endoscopy at 0.58 (95% CI: 0.40–0.74) and again no statistically significant difference was observed (p = 0.457, Q = 0.55) (‘’). An assessment of publication bias on the efficacy of VCE yielded a value of p = 0.63 indicating that no publication bias was present.

Completion rate and complication rate of VCE

Gastric retention (defined as capsule remaining in the stomach for 8 h) was reported in 7.6% (22/289) of all examinations with no cases of capsule retention below the pylorus. Occasionally, the administration of metoclopramid or the advancement of the capsule with a polypectomy snare into the duodenum were used to shorten the gastric passage time and save battery time. Other reported complications included emesis, in one study. In total, a complete VCE procedure was obtained in 88% (209/237) of the examinations ranging from 74–95%. The data was retrieved from four studies consisting of totally 237 examinations [Citation26–28,Citation30] (‘’).

Table 2. Overview of study, population characteristics, and findings from VCE/conventional endoscopy/histopathology.

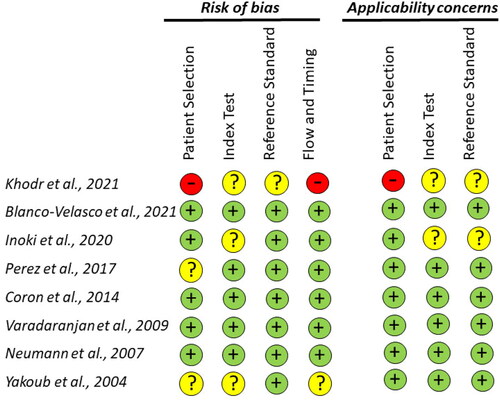

Quadas-2

According to the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 tool, one article scored as having high risk of bias (patient selection bias) [Citation25] whereas further three had an unclear risk, mostly because it did not adequately describe their study population in detail (i.e., how the patients were recruited as well as inclusion and exclusion criteria). In addition, two out of eight studies failed in data management because institutional ethical approval was not reported. The risk of bias for the included studies is detailed in ’’.

Discussion

The current analysis shows that the correlation between histology and VCE findings in these studies were at least comparable to conventional endoscopies. The examinations were also clinically deemed to be useful by the clinicians in the setting it was administered in. Moreover, a concern that often limits the use of VCE is the fear of severe adverse events such as intestinal obstruction due to capsule retention in the small intestine, which may require surgical exploration. In our analysis, none of the capsules were retained in the small bowel although gastric retention due to impaired gastric motility was relatively high.

Furthermore, the frequency of incomplete examinations was at an average of 12% ranging from 5–26%. The data was retrieved from four studies consisting of totally 237 examinations [Citation26–28,Citation30] which is acceptable according to European recommendation [Citation33]. Overall, the retention rate seems to have declined globally over the past two decades [Citation34] it still occurs at varying frequencies, depending on the indications, ranging from 2% in gastrointestinal bleeding [Citation35] to 8–13% in Crohn’s disease [Citation36,Citation37]. However, these patients do not seem to have an elevated risk of retention if other complicating factors are not present. Therefore, the use of VCE in this patient cohort appeared safe since no serious adverse events were detected. The use of patency capsule is therefore not necessary if additional risk factors are not present. Several strategies such as administering propulsive agents prior to the procedure or placing the capsule directly in the duodenum with the help of a gastroscope may increase the completion rate by shortening the time spent in the stomach and saving battery time for the examination of the small and large intestine. Similarly, the use of Simethicone and bowel preparation would likely play a role in improving the visualization of the small bowel [Citation38] but these agents seem to have been used in less than half of the patients.

The role of VCE in GVHD is yet to be determined, even though VCE has become an important investigation and has been used for the evaluation of a variety of small bowel conditions [Citation37]. International standards have been set in both Europe and U.S as when to perform these examinations and how to appropriate quality measures to assess the proficiency of a unit to perform investigations [Citation33,Citation39]. Unfortunately, this experience and recommendations have not been extended to patients who have undergone HSCT and thus this paper represents the first systematic review within this field for this cohort of patients.

The golden standard for diagnosing intestinal GVHD has historically relied on endoscopy with biopsies along with clinical features. Due to the frequent appearance of patchy distribution of endoscopic findings in acute GVHD, the importance to obtain biopsies from multiple sites has been adequately stressed. The American Society of gastroenterology suggests two potential approaches in patients with suspected GVHD. One strategy is to retrieve four samples from the rectosigmoid and the descending colon. If these results are inconclusive a gastroscopy with sampling from the esophagus, antrum, gastric body and duodenum is recommended. Alternatively, an ileocolonoscopy with sampling from each anatomic region along with any sections depicting diffuse findings [Citation40] can be performed.

Nevertheless, these strategies are suboptimal for several reasons. Conventional endoscopy only examines a small segment of the small bowel while biopsies have the potential risk of creating severe intramural hematoma with a wound that may not heal due to defects in epithelial cell regeneration and thrombocytopenia. Additionally, the result may not be conclusive due to the inability to obtain deep biopsies since alterations most often are encountered in the deep portions of the crypts extending to the muscularis mucosa [Citation41]. Regardless of this, tissue sampling is important for the diagnosis of GVHD but should not delay the management of the disease in patients with classical findings [Citation42,Citation43].

The potential role of VCE therefore seems appealing for these patients i.e., to diagnose GVHD based on clinical appearance using a non-invasive technique. However, the drawback of not being able to obtain biopsies is apparent [Citation32,Citation44]. An alternative approach to bridge this discrepancy might have been to rely on typical VCE findings on its own and selectively performing either upper, lower, or deep enteroscopy to secure targeted biopsies in cases where inconclusive findings were observed.

Unfortunately, the methodology to estimate the usefulness of VCE is flawed in present studies due to the fact that histology captured with conventional endoscopy is compared with VCE which may include findings beyond the reach of conventional endoscopy, and thereby underestimating its accuracy. The diagnostic yield of conventional endoscopy when compared to histology has shown to have higher accuracy in lower endoscopy (80–90%) when compared to upper endoscopy (60–70%) with the highest yield being in situations where a combination of both upper and lower endoscopies are performed (>90%) simultaneously [Citation45–47]. This highlights the benefit of visualizing a larger segment of the GI tract since GVHD may occur throughout the tract either localized or diffusely spread [Citation48].

The advantage of VCE should therefore be balanced against the disadvantage of not receiving tissue samples. Previous reports have found histological signs of acute GVHD in 44 to 84% of biopsies sampled from endoscopically normal biopsy sites [Citation46,Citation47], emphasizing the need to biopsy normal as well as abnormal mucosa. In addition, one may consider the refinement of current endoscopic descriptors i.e., the Freiburg Criteria [Citation49]. With added descriptors focusing on milder disease such as loss of vascular markings and/or focal mild erythema the score has a possibility for improvement. To achieve an increased diagnostic yield and compensate for the shortcomings of visual impression, the use of artificial intelligence using deep learning would likely results in an improved interpretation of the given findings and perhaps an earlier diagnosis [Citation50,Citation51].

The current analysis has the shortcomings typical for many systematic reviews, namely a low number of available reports and a small sample size for most of the included studies. Another relative limitation was that many studies were retrospective (50% of the studies and 78% (183/232) of the patients) and endoscopists were likely not blinded to the clinical history. However, VCE readings appeared to have been performed prior to the retrieval of histopathology reports. Another limitation was that VCE examinations were mainly focused to the small intestine whereas the biopsies were sampled from either the proximal GI tract, the colon or both. Moreover, the VCE patients consisted of a selected patient cohort which further lowered the overall study quality.

Additionally, this analysis was exclusively focused on GVHD, it is still necessary to establish the value of VCE in diagnosing and managing other GI complications after HSCT, particularly viral (CMV) enteritis, which represent an important differential and a frequent complication after HSCT [Citation52,Citation53]. As the viral load surveillance through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be used as an adjunct, the role of VCE is perhaps to monitor the treatment response and as a complimentary measure to evaluate the extent of the disease during the initial diagnosis. Moreover, early recognition of severe gut GVHD may also help select adequate treatment promptly.

In conclusion, our systematic review of eight studies consisting of 232 patients undergoing VCE after HSCT refutes the notion that capsule endoscopy is unsafe and leads to obstructive symptoms within this patient cohort. Moreover, when aptly performed the investigation may yield useful information although its place in diagnosing or dismissing GVHD is yet to be established and requires further studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405(6785):417.

- Enns RA, Hookey L, Armstrong D, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the use of video capsule endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(3):497–514.

- de Sousa Magalhães R, Rosa B, Marques M, et al. How should we select suspected crohn’s disease patients for capsule enteroscopy? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(8):991–997.

- Hosoe N, Takabayashi K, Ogata H, et al. Capsule endoscopy for small-intestinal disorders: current status. Dig Endosc. 2019;31(5):498–507.

- Eliakim R, Magro F. Imaging techniques in IBD and their role in follow-up and surveillance. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11(12):722–736.

- Pennazio M, Spada C, Eliakim R, et al. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: european society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) clinical guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47(4):352–376.

- Robertson AR, Yung DE, Douglas S, et al. Repeat capsule endoscopy in suspected gastrointestinal bleeding. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(5):656–661.

- Rondonotti E, Spada C, Adler S, et al. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: european society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) technical review. Endoscopy. 2018;50(4):423–446.

- Bolwell JG, Wild D. Indications, contraindications, and considerations for video capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2021;31(2):267–276.

- Niederwieser D, Baldomero H, Bazuaye N, et al. One and a half million hematopoietic stem cell transplants: continuous and differential improvement in worldwide access with the use of non-identical family donors. Haematologica. 2022;107(5):1045–1053.

- Cox GJ, Matsui SM, Lo RS, et al. Etiology and outcome of diarrhea after marrow transplantation: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(5):1398–1407.

- Ghimire S, Weber D, Mavin E, et al. Pathophysiology of GvHD and other HSCT-Related major complications. Front Immunol. 2017;8:79.

- Altun R, Gökmen A, Tek İ, et al. Endoscopic evaluation of acute intestinal graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2016;27(4):312–316.

- Zeiser R, Blazar BR. Acute graft-versus-Host Disease - Biologic process, prevention, and therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(22):2167–2179.

- Daniel F, Hassoun L, Husni M, et al. Site specific diagnostic yield of endoscopic biopsies in gastrointestinal graft-versus-Host disease: a tertiary care center experience. Curr Res Transl Med. 2019;67(1):16–19.

- Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160.

- McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–46.

- Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, PRISMA-S Group, et al. PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):39.

- Ouzzani. 2016. www.rayyan.ai

- Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, QUADAS-2 Group, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–536.

- R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2022. https://www.R-project.org/

- Lee J, Kim KW, Choi SH, et al. Systematic review and Meta-Analysis of studies evaluating diagnostic test accuracy: a practical review for clinical Researchers-Part II. Statistical methods of Meta-Analysis. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16(6):1188–1196.

- Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L. The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(9):882–893.

- van Enst WA, Ochodo E, Scholten RJ, et al. Investigation of publication bias in meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy: a meta-epidemiological study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:70.

- Khodr J, Zerbib P, Rogosnitzky M, et al. Diverting enterostomy improves overall survival of patients With severe steroid-refractory gastrointestinal acute Graft-Versus-Host disease. Ann Surg. 2021;274(5):773–779.

- Blanco-Velasco G, Palos-Cuellar R, Dominguez-Garcia MR, et al. Utility of capsule endoscopy in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (Engl Ed). 2021;86(3):215–219.

- Inoki K, Kakugawa Y, Takamaru H, et al. Capsule endoscopy after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can predict Transplant-Related mortality. Digestion. 2020;101(2):198–207.

- Perez-Cuadrado-Robles E, Castilla-Llorente C, Queneherve L, et al. Short article: capsule endoscopy in graft-versus-host disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(4):423–427.

- Coron E, Laurent V, Malard F, et al. Early detection of acute graft-versus-host disease by wireless capsule endoscopy and probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy: results of a pilot study. United European Gastroenterol J. 2014;2(3):206–215.

- Varadarajan P, Dunford LM, Thomas JA, et al. Seeing what’s out of sight: wireless capsule endoscopy’s unique ability to visualize and accurately assess the severity of gastrointestinal graft-versus-host-disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(5):643–648.

- Neumann S, Schoppmeyer K, Lange T, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy for diagnosis of acute intestinal graft-versus-host disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(3):403–409.

- Yakoub-Agha I, Maunoury V, Wacrenier A, et al. Impact of small bowel exploration using Video-Capsule endoscopy in the management of acute gastrointestinal graft-versus-Host disease. Transplantation. 2004;78(11):1697–1701.

- Spada C, McNamara D, Despott EJ, et al. Performance measures for small-bowel endoscopy: a european society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) quality improvement initiative. Endoscopy. 2019;51(6):574–598.

- Wang YC, Pan J, Liu YW, et al. Adverse events of video capsule endoscopy over the past two decades: a systematic review and proportion meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20(1):364.

- Cheifetz AS, Lewis BS. Capsule endoscopy retention: is it a complication? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40(8):688–691.

- Cheifetz AS, Kornbluth AA, Legnani P, et al. The risk of retention of the capsule endoscope in patients with known or suspected crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2218–2222.

- Rezapour M, Amadi C, Gerson LB. Retention associated with video capsule endoscopy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85(6):1157–1168.e2.

- Keuchel M, Kurniawan N, Bota M, et al. Lavage, simethicone, and Prokinetics-What to swallow with a video capsule. Diagnostics. 2021;11(9):1711.

- Wang A, Banerjee S, Barth BA, ASGE Technology Committee, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78(6):805–815.

- Sharaf RN, Shergill AK, Odze RD, ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, et al. Endoscopic mucosal tissue sampling. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78(2):216–224.

- Shulman HM, Kleiner D, Lee SJ, et al. Histopathologic diagnosis of chronic graft-versus-host disease: national institutes of health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-Host disease: II. Pathology working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(1):31–47.

- Martin PJ, Rizzo JD, Wingard JR, et al. First- and second-line systemic treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease: recommendations of the American society of blood and marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(8):1150–1163.

- Dignan FL, Clark A, Amrolia P, British Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute graft-versus-host disease. Br J Haematol. 2012;158(1):30–45.

- Naymagon S, Naymagon L, Wong SY, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease of the gut: considerations for the gastroenterologist. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(12):711–726.

- Scott AP, Tey SK, Butler J, et al. Diagnostic utility of endoscopy and biopsy in suspected acute gastrointestinal graft-versus-Host disease after hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(6):1294–1298.

- Thompson B, Salzman D, Steinhauer J, et al. Prospective endoscopic evaluation for gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease: determination of the best diagnostic approach. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(5):371–376.

- Rajan AV, Trieu H, Chu P, et al. Assessing the yield and safety of endoscopy in acute graft-vs-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplant. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;12(10):341–354.

- Kreft A, Neumann H, Schindeldecker M, et al. Diagnosis and grading of acute graft-versus-host disease in endoscopic biopsy series throughout the upper and lower intestine in patients after allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a systematic approach. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60(6):1512–1521.

- Kreisel W, Dahlberg M, Bertz H, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis of acute intestinal GVHD following allogeneic hematopoietic SCT: a retrospective analysis in 175 patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47(3):430–438.

- Wang X, Qian H, Ciaccio EJ, et al. Celiac disease diagnosis from videocapsule endoscopy images with residual learning and deep feature extraction. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;187:105236.

- Soffer S, Klang E, Shimon O, et al. Deep learning for wireless capsule endoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(4):831–839.e8.

- Teira P, Battiwalla M, Ramanathan M, et al. Early cytomegalovirus reactivation remains associated with increased transplant-related mortality in the current era: a CIBMTR analysis. Blood. 2016;127(20):2427–2438.

- Gilioli A, Messerotti A, Bresciani P, et al. Cytomegalovirus reactivation after hematopoietic stem cell transplant with CMV-IG prophylaxis: a monocentric retrospective analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93(11):6292–6300.