Abstract

Objectives

To explore the utilization of three-dimensional (3D) endoanal ultrasound (EAUS) for the follow-up of the anal fistula plug (AFP), describe morphological findings in postoperative 3D EAUS, and evaluate if postoperative 3D EAUS combined with clinical symptoms can predict AFP failure.

Materials and methods

A retrospective analysis of 3D EAUS examinations performed during a single-centre study of prospectively included consecutive patients treated with the AFP between May 2006 and October 2009. Postoperative assessment by clinical examination and 3D EAUS was performed at 2 weeks, 3 months and 6–12 months (“late control”). Long-term follow-up was carried out in 2017. The 3D EAUS examinations were blinded and analysed by two observers using a protocol with defined relevant findings for different follow-up time points.

Results

A total of 95 patients with a total of 151 AFP procedures were included. Long-term follow-up was completed in 90 (95%) patients. Inflammation at 3 months, gas in fistula and visible fistula at 3 months and at late control, were statistically significant 3D EAUS findings for AFP failure. The combination of gas in fistula and clinical finding of fluid discharge through the external fistula opening 3 months postoperatively was statistically significant (p < 0.001) for AFP failure with 91% sensitivity and 79% specificity. The positive predictive value was 91%, while the negative predictive value was 79%.

Conclusions

3D EAUS may be utilized for the follow-up of AFP treatment. Postoperative 3D EAUS at 3 months or later, especially if combined with clinical symptoms, can be used to predict long-term AFP failure.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03961984

Introduction

The anal fistula plug (AFP) was introduced in 2005 as a sphincter-preserving treatment option for complex anal fistulas. Reported success rates vary between 13–100%, with declining success rates with longer follow-up time [Citation1–3]. In a small number of studies, follow-up included magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for some of the participants [Citation4,Citation5], but no systematic studies describe the morphological findings related to healing and failure after the AFP. Preoperative three-dimensional (3D) endoanal ultrasound (EAUS) is reportedly accurate and reproducible in defining height and type of anal fistulas, and it has been shown to be better than MRI at detecting internal fistula openings [Citation6–11]. Since 3D EAUS is a rapid examination usually well-tolerated by patients, it should be a feasible alternative for postoperative control after the AFP and other sphincter-preserving fistula procedures. However, documented knowledge is very limited when it comes to radiological follow-up after the AFP, especially with 3D EAUS.

This study aimed to explore the utilization of 3D EAUS for the follow-up of the AFP treatment. We described morphological findings in postoperative 3D EAUS at different time points after the AFP procedure and evaluated if postoperative 3D EAUS combined with clinical symptoms may be used to predict AFP failure.

Materials and method

Study design and patient selection

Inclusion in this single-centre prospective cohort study took place between May 2006 and October 2009. Consecutive patients with complex fistulas in need of surgical treatment at a referral centre were eligible for enrolment. All fistulas where the first-line treatment did not include a simple fistulotomy were considered to be “complex”, i.e., if the tract involved more than 30–50% of the anal sphincter length (depending on fistula orientation), or if the patient had a history of Crohn’s disease, incontinence, or local irradiation. Anterior fistulas in female patients were also considered to be “complex”. Patients with ano/rectovaginal fistulas were excluded. All patients meeting the inclusion criteria were initially assessed by physical examination and 3D EAUS at the out-patient clinic. The patients were treated with a draining loose seton for at least 6 weeks before the AFP procedure. Follow-up included physical examination and 3D EAUS at predefined intervals up to 12 months after surgery. For the purpose of this study, all 3D EAUS examinations were analysed retrospectively as described below.

Ethical considerations

The regional ethics committee approved the study protocol. All patients provided informed consent. Procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committees and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. The study has been retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03961984) with a release date 05/08/2019.

Surgical procedure

A mini enema was used as a preoperative bowel preparation. The lithotomy position was used during the surgical procedure which was performed under general anaesthesia. 3D EAUS was performed perioperatively to guarantee that no further tracts or undrained abscesses were present. The Surgisis (Biodesign) anal fistula plug was placed in the fistula tract using a standardised procedure [Citation12].

3D EAUS

The patients were followed up with a standardised 3D EAUS combined with a clinical examination at two weeks, three months and between six to twelve months (“late control”) postoperatively. The ultrasound examinations were performed by using a 3D Pro Focus machine (BK Medical, Herlev, Denmark) and 360° rotating 13 MHz transducer. The ultrasound investigation included the whole anal canal and the distal part of rectum, and the soft tissues with a radius of 47 mm from the centre of the probe. Water-soluble lubricant was applied on a covering condom containing water-soluble contact gel for ultrasound (Lectro Derm 1, Handelshuset Viroderm AB, Solna, Sweden) before introducing the probe into the anal canal.

The ultrasound examinations were coded and retrospectively analysed by a team of two colorectal surgeons with extensive experience in anal fistula surgery and 3D EAUS. First, ultrasound examinations of 10 random patients were analysed exploratory to identify which findings were most prevalent. Based on this, a protocol for the analysis of examinations was set up and used for all examinations. The surgeons were blinded to the outcome. The reviewers analysed the examinations together, and in case of disagreement, consent was resolved by discussion.

Follow-up

After the three postoperative controls with 3D EAUS, patients were advised to contact the clinic at any time if they had symptoms of fluid discharge, perianal infection, or external fistula openings. Healing of the fistula tract was defined by a closed external opening, the absence of discharge and no additional fistula surgery. Patients not known to have undergone any further fistula surgery received a questionnaire regarding symptoms of fistula recurrence in August 2017. Patients reporting any symptoms of recurrence were assessed by 3D EAUS and clinical examination.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics are presented as median (range) or frequency (percent), as appropriate. Comparisons between categorical variables were made using Fisher’s exact test, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All P values correspond to two-sided tests. The parameters that were identified as statistically significant were also analysed with a logistic regression model. The analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Characteristics of the 95 patients included in the study are listed in . Thirty patients had quiescent Crohn’s disease (18 male, 12 female; median age: 34 years; age range 10–66 years), and 65 patients (43 male, 22 female; median age: 46 years; age range: 21–80 years) had been diagnosed with cryptoglandular fistulas.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants in the study at inclusion. Values are given as median (range) or n (%).

Follow-up and fistula healing

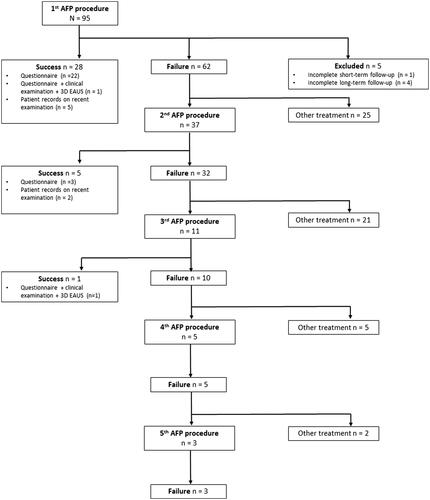

Five patients were lost to follow-up, after participation time ranging from 4 to 30 months. After a median follow-up of 110 (range: 93–138) months, the overall healing rate after one to five AFP procedures was 38% (34/90). No further success was observed after three AFP procedures. summarises the treatment and follow-up process. Since 37 patients received more than one plug during the study period, a total of 151 plug procedures were performed in this study. 146 plug procedures were analysed, as five patients were excluded due to incomplete follow-up.

3D EAUS parameters

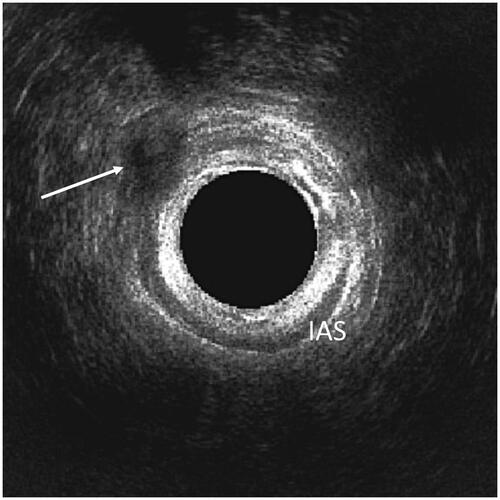

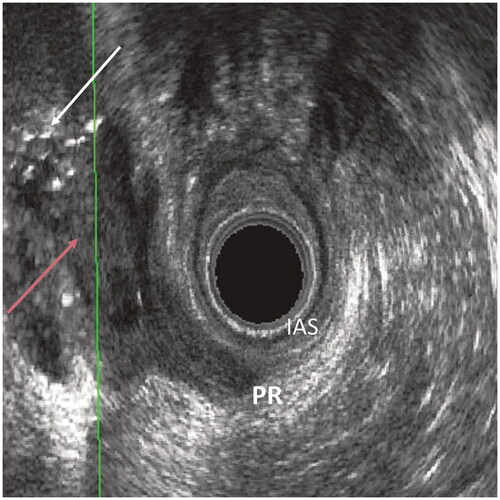

The 3D EAUS findings identified as relevant for all the three-time points in the analysis of examinations from ten random patients were the presence of gas or residual fluid in the fistula tract. The presence of inflammatory reaction at the operation site was analysed for the 3D EAUS examinations at two weeks and three months. Visible sutures were noted for examinations at two weeks and three months. The examinations at three months and late control were also analysed for any signs of the fistula still being visible. and show examples of the relevant 3D EAUS findings.

Postoperative 3D EAUS

summarises the relevant 3D EAUS findings related to the results of the plug procedure as identified in the long-term follow-up. Gas in fistula, surgical site inflammation, and visible fistula at 3 months were statistically significant findings for AFP failure. At the late control, gas in fistula and visible fistula were significantly associated with AFP failure.

Table 2. The relevant 3D EAUS findings related to the results of the AFP procedure as identified in the long-term follow-up. Values are given as n(positive parameter)/n(plugs in group) and (%).

None of the parameters at 2 weeks were statistically significant for AFP failure. Sutures were visible in 105 of 118 examinations (89%) at 2 weeks and in 22 of 90 examinations (24%) at 3 months, with no statistically significant differences between the groups for failure and healing. Residual fluid in the fistula tract was identified in 7 of 126 examinations (6%) at 2 weeks, 4 of 98 examinations (4%) at 3 months, and 1 of 63 examinations (2%) at late control, with no statistically significant differences between the groups.

Diagnostic probabilities for AFP failure based on the relevant 3D EAUS findings are summarised in . A logistic regression model was used to analyse these parameters, and the results are shown in .

Table 3. Diagnostic probabilities for AFP failure based on 3D EAUS findings. PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value.

Table 4. Odds for AFP failure based on logistic regression model analysis of the relevant 3D EAUS findings. 95% CI = 95% Confidence Interval.

Plug failure: clinical symptoms and 3D EAUS

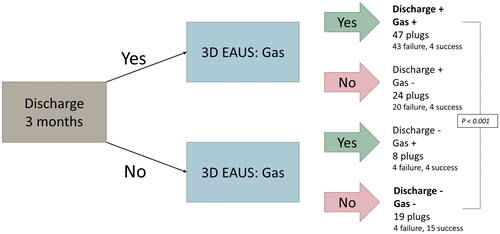

When the 3D EAUS finding of the presence of gas in the fistula tract was combined with the clinical symptom of the presence of fluid discharge through the external fistula opening 3 months postoperatively, 47 plugs (43 failure, 4 success) were reported to be positive for both. 19 plugs (15 success, 4 failure) were reported to be negative for both parameters. The relationship between “the double positive plugs” and “the double negative plugs” was statistically significant (p < 0.001). presents the result algorithm for this part of the study. The presence of both gas and discharge 3 months after the AFP procedure had 91% sensitivity and 79% specificity for AFP failure. The positive predictive value (PPV) for plug failure was 91%, while the negative predictive value (NPV) was 79%.

Figure 4. Result algorithm for the relationship between the clinical symptom of fluid discharge through the external fistula opening combined with the 3D EAUS parameter of gas in fistula 3 months after the AFP procedure analysed in relation to AFP failure for “the double positive” and “double negative” plugs (Fischer’s exact test, p < 0.001).

Discussion and conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report the most prevalent morphological findings at postoperative 3D EAUS that can be utilized for the follow-up of the AFP treatment. We found that the 3D EAUS finding of the presence of gas in the fistula tract may be combined with the clinical symptom of the presence of fluid discharge through the external fistula opening 3 months postoperatively to predict long-term AFP failure with 91% sensitivity and 79% specificity.

In this study, a visible fistula at 3D EAUS both 3 months and late control after the AFP procedure was associated with AFP failure. This had high sensitivity for fistula recurrence (95% or more), but the specificity was only 20% at 3 months and 53% at late control, indicating that the fistula is still seen as a hypoechogenic area even at the 3D EAUS investigations performed on patients who show no signs of AFP failure in the long-term follow-up. In 2019, Garg reported a study of 702 patients who had been investigated with a preoperative MRI and after that operated on either with fistulotomy or transanal laying-open of intersphincteric tract [Citation13]. A postoperative MRI was performed in 108 (15%) of these patients. The author noticed that granulation tissue and postsurgical inflammation were difficult to differentiate from active fistula as both looked hyperintense on T2-weighted images and short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences, especially during the first 8 weeks after surgery. After complete healing, the fistula tract became hypointense on T2 and STIR, but was still visible.

Few studies discuss radiological healing after the AFP, and documented knowledge is very limited. A retrospective analysis of 63 patients who had been treated with the AFP reported 81% clinical healing rate one year after surgery [Citation4]. Eight out of 51 patients with healing volunteered to undergo MRI, and no evidence of fistula or presence of fluid in the area of previous fistula was seen in 6 (75%) patients. Two patients had residual fluid and fistula tract but showed no signs of clinical recurrence after 14–17 months. Another study had 106 patients with Crohn’s disease drained with a seton and then randomized to either the AFP or seton removal after more than one month of drainage [Citation5]. Fistula closure rate of 32% was reported after 12 weeks for 54 patients treated with AFP compared to 23% in the control group (seton removal alone), p = 0.19. MRI was performed in 25 patients in the AFP group 12 weeks after surgery, and fistula tract healing was observed in 6 patients (24%). This was defined by the absence of T2 hyperintensity, cavities and/or abscesses and no sign of rectal wall involvement. In the present study, residual fluid in the area of fistula was diagnosed in a limited extent (2–6% of AFP procedures) and had no statistical significance in identifying AFP failure. Our interpretation is that fluid residuals should not be the main morphological focus of postoperative 3D EAUS after sphincter-preserving anal fistula procedures since there are other findings that are more appropriate.

Our study identifies the presence of gas in the fistula tract as a morphological postoperative 3D EAUS finding associated with long-term AFP failure. Gas is a strong ultrasound reflector and is readily identified, as seen in . It has relatively high specificity and PPV for AFP failure, but low sensitivity. One study has documented the use of 3D EAUS to follow-up patients who underwent ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT), but the authors do not list gas in fistula as a parameter that has been investigated [Citation14]. Since no previous studies report the use of 3D EAUS after the AFP surgery, more studies are needed on the presence of postoperative gas in fistula tract after sphincter-preserving treatments, especially in procedures leading to refilling the fistula tract.

The results of this study show that the presence of gas in the fistula tract at 3D EAUS could be combined with the presence of fluid discharge through the external fistula opening 3 months after the AFP procedure to identify patients at high risk for AFP failure. Our previous paper has reported that the presence of discharge alone 3 months after the AFP procedure in the same study cohort had 76% sensitivity and 77% specificity for plug failure, with PPV 90% and NPV 58% [Citation12]. Focusing on the double positive (both gas and discharge) and the double negative (neither gas nor discharge) patients strengthens the possibility to identify patients at high risk for AFP failure with 91% sensitivity and 79% specificity. The NPV of 79% makes it also easier to predict that the double negative patients have a relatively good chance of AFP success.

This study has some limitations that should be addressed. Since no previous studies were available, we were obliged to analyse 3D EAUS examinations for several morphological findings at different time points in order to find the most prevalent ones. Some 3D EAUS examinations were difficult to analyse for a specific parameter or due to generally poor picture quality, and some examinations were missing due to technical reasons, leading to the risk of information bias. Also, the limited number of plugs in AFP success group contributed to large confidence intervals in the logistic regression models which in turn led to a conclusion that the association is too unspecific to allow multiple regression analysis on the data. It should also be noted that the new generation of 3D EAUS machines and probes used today have higher image quality and resolution that the equipment used in the current study.

Local factors, such as economic issues, clinical traditions, and availability, may largely affect the radiological follow-up of the AFP treatment. Besides this, it may be difficult to motivate patients with no symptoms of fistula recurrence to undergo MRI for postoperative control. The benefits of 3D EAUS are that the investigation is readily accessible and easy to perform as a part of the clinical examination at the out-patient clinic. Our results show that there is no need for routine for early 3D EAUS at 2 weeks postoperatively. Three months after the AFP procedure it is possible to identify patients with both fluid discharge through external fistula opening and the presence of gas in the fistula tract. These patients have >90% risk for AFP failure and should be planned for a follow-up clinical examination and 3D EAUS. Reintervention is recommended if the fluid discharge does not cease during the upcoming months. Early reintervention is recommended should there be obvious signs of AFP failure. On the other hand, patients with completely dry external openings and no sign of gas in the fistula tract are at low risk for AFP failure. There is no need for further follow-up of these patients since eventual fistula recurrence may take years to develop [Citation12]. The double negative group should only be informed to contact the clinic if any signs of AFP failure occur. Patients with either gas in the fistula tract or discharge through the external opening are suggested to be booked for a follow-up clinical examination and 3D EAUS.

This study shows that 3D EAUS can be used for the radiological follow-up of the AFP treatment. We identify the presence of gas in the fistula tract at three months and late control as an appropriate and easily identified morphological finding for AFP failure. Although the use of AFP treatment has reduced over the past years, we believe that the results of this study are highly relevant for the evaluation of novel regenerative fistula treatment methods, such as Obsidian RFT. Further systematic studies are needed to explore the role of 3D EAUS in postoperative follow-up of anal fistula treatments. In conclusion, this study demonstrates that 3D EAUS can be utilized for the follow-up of the AFP treatment. Postoperative 3D EAUS at three months or later, especially if combined with clinical symptoms, may be used to predict long-term AFP failure.

Parts of the study have been presented as a poster at the meeting of European Society of Colorectal Surgery, Wien, Austria, 25–27 September 2019.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kontovounisios C, Tekkis P, Tan E, et al. Adoption and success rates of perineal procedures for fistula-in-ano: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18(5):441–458.

- O’Riordan JM, Datta I, Johnston C, et al. A systematic review of the anal fistula plug for patients with Crohn’s and non-Crohn’s related fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(3):351–358.

- Tan KK, Kaur G, Byrne CM, et al. Long-term outcome of the anal fistula plug for anal fistula of cryptoglandular origin. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15(12):1510–1514.

- Ellis CN, Rostas JW, Greiner FG. Long-term outcomes with the use of bioprosthetic plugs for the management of complex anal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(5):798–802.

- Senejoux A, Siproudhis L, Abramowitz L, et al. Fistula plug in fistulising ano-perineal Crohn’s disease: a randomised controlled trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10(2):141–148.

- Kołodziejczak M, Santoro GA, Obcowska A, et al. Three-dimensional endoanal ultrasound is accurate and reproducible in determining type and height of anal fistulas. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19(4):378–384.

- Siddiqui MR, Ashrafian H, Tozer P, et al. A diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis of endoanal ultrasound and MRI for perianal fistula assessment. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(5):576–585.

- Subasinghe D, Samarasekera DN. Comparison of preoperative endoanal ultrasonography with intraoperative findings for fistula in ano. World J Surg. 2010;34(5):1123–1127.

- Brillantino A, Iacobellis F, Di Sarno G, et al. Role of tridimensional endoanal ultrasound (3D-EAUS) in the preoperative assessment of perianal sepsis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30(4):535–542.

- Sudoł-Szopińska I, Geśla J, Jakubowski W, et al. Reliability of endosonography in evaluation of anal fistulae and abscesses. Acta Radiol. 2002;43(6):599–602.

- Kim Y, Park YJ. Three-dimensional endoanal ultrasonographic assessment of an anal fistula with and without H(2)O(2) enhancement. World J Gastroenter ol. 2009;15(38):4810–4815.

- Aho Fält U, Zawadzki A, Starck M, et al. Long-term outcome of the Surgisis(®) (Biodesign(®)) anal fistula plug for complex cryptoglandular and Crohn’s fistulas. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23(1):178–185.

- Garg P. Comparison of preoperative and postoperative MRI after fistula-in-ano surgery: lessons learnt from an audit of 1323 MRI at a single centre. World J Surg. 2019;43(6):1612–1622.

- Murad-Regadas SM, Regadas Filho FSP, Holanda EC, et al. Can three-dimensional anorectal ultrasonography be included as a diagnostic tool for the assessment of anal fistula before and after surgical treatment? Arq Gastroenterol. 2018;55 (Suppl 1):18–24.