Abstract

Objectives

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal condition. A respectful patient-doctor relationship with good communication is crucial for optimal treatment. Q-methodology is a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods used to study subjectivity. The aim of this study was to compare viewpoints on IBS between patients with IBS and general practitioners (GPs).

Methods

We conducted a Q-methodology study by including 30 patients and 30 GPs. All participants were asked to complete Q- sorting of 66 statements on IBS using an online software program. Data were processed using factor analysis. In addition, 3 patients and 3 GPs were interviewed.

Results

Three factors were extracted from both groups: Patient Factor 1 ‘Question the diagnosis of IBS’, Patient Factor 2 ‘Lifestyle changes for a physical disorder’, Patient Factor 3 ‘Importance of a diagnosis’, GP Factor 1 ‘Unknown causes of great suffering’, GP Factor 2 ‘Lifestyle changes are important, stress makes IBS worse’, GP Factor 3 ‘Recognized the way IBS affects patients’. There was a strong and statistically significant correlation between patient Factor 1 and GP Factor 1, with a Pearson’s r of 0.81 (p < 0.001). Correlations between other factors varied.

Conclusions

There was consensus between patients and GPs that IBS is a physical and not a psychiatric disorder of unknown etiology. They also seemed to agree that IBS has a great negative impact on patients’ lives and that lifestyle changes are beneficial. There were conflicting opinions regarding gender, cultural factors and the use of antidepressants.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional condition of the digestive system affecting approximately 11% of the population globally. It occurs in all age groups, more often in women, but with no clear correlation to socioeconomic factors [Citation1]. A diagnosis of IBS is made using the Rome criteria, a symptom-based classification [Citation2]. Symptoms of IBS include varying degrees of abdominal pain in combination with changes in bowel habits, such as the frequency and appearance of stool. The pathogenesis of IBS is multifactorial, and several underlying mechanisms are believed to contribute to the development of symptoms, including abnormalities in gastrointestinal sensation, motility, microbiota, permeability, and immune activation [Citation3]. It has also been suggested that IBS is primarily a gut-brain disorder or caused by somatization, but recent epidemiological data suggest that psychological symptoms are secondary to pathophysiological changes in the gastrointestinal system in at least a subgroup of patients [Citation4].

Previous studies have shown that patients perceive IBS as a chronic condition that negatively impacts their lives and receive inadequate support or understanding from their healthcare providers. Patients tend to associate IBS with loss of freedom and spontaneity as well as with shame and embarrassment, leading to a decreased quality of life [Citation5,Citation6]. According to a survey, most patients with IBS have a negative view of their healthcare providers, emphasizing the need for better communication [Citation7]. Furthermore, a qualitative study from 2011 revealed a gap between the explanatory models for IBS among general practitioners (GPs) and the expectations of patients with IBS [Citation8].

Q-methodology was first introduced in the 1930s by psychologist W. Stephenson, and it can be described as a mixed method combining both qualitative and quantitative methods. It was developed for the systematic study of subjectivity and has gained popularity in multiple fields, including health care [Citation9,Citation10].

A Q- methodology study from 2000 aimed to discover how IBS patients understand the nature and causality of their condition resulted in seven different subgroups of patients with respect to their viewpoints regarding IBS [Citation11]. A later study from the United Kingdom instead explored the viewpoints of GPs on IBS. In short, they found that GPs share the viewpoint that IBS is a disorder mostly caused by psychological factors [Citation12].

The aim of this study was to compare the views of both patients and GPs regarding IBS in a Swedish primary health care setting by using a Q-methodology design.

Methods

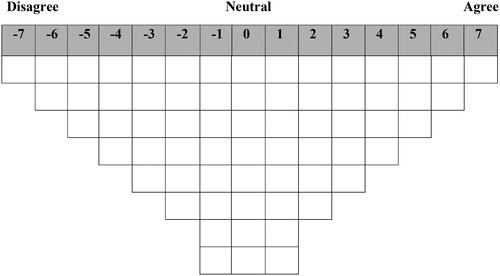

The first step in Q-methodology is the development of a ‘concourse’, i.e., a set of possible statements covering the topic to be studied. The researcher gathers views and opinions from multiple sources, including literature, previous studies, interviews, and internet forums. The statements are then repeatedly evaluated within the research group and scrutinized to avoid ambiguity, repetition and to decrease the risk of bias. After the final selection of statements, the so-called ‘Q-set’ is constructed. Usually, a Q-set consists of 40-80 statements. Once included in the study, participants from the study population are asked to sort these statements according to their own beliefs and to place them on a grid () that can be considered as a forced quasi-normal distribution of statements being ranked from ‘totally agree’ to ‘totally disagree’ [Citation13]. Each participant’s ranked statements are turned into an array of numerical data that is then compared with the arrays of all other participants. The correlation matrix reveals which persons completed their sorts in similar order [Citation14]. Factor analysis is then used to examine the correlation matrix, telling us how many groups of similarly ranked variables there are, i.e., it determines the factors. The extracted factors, usually between 3 and 6, represent different shared conceptions about the subject to be studied [Citation15]. Finally, some participants are usually interviewed to collect further qualitative data about their rankings [Citation13].

We used a total of 66 statements, derived from previous studies [Citation11,Citation12]. Our research group evaluated these statements and translated them into Swedish. Subsequently, they were modified to be relevant for both patients and GPs, and some statements were simplified or altered to be more relevant to the Swedish conditions (see Supplementary Material 2). We transferred this Q-set to www.qmethodsoftware.com, which is a dedicated software program for Q-sorting, and evaluated the statements to confirm that the language was understandable and that the Q-set could be distributed within the forced-choice grid without conflicts.

Subsequently, all participants were asked to perform Q-sorting online via the abovementioned software.

Thirty IBS patients (6 men and 24 women) and 30 GPs (14 men and 16 women) living and working in Region Örebro County (RÖC), respectively, were included in the study. There are no exact rules regarding sample sizes in q-methodology and the number of participants may vary from only a few to 60 [Citation16]. Patients were recruited by advertisements, via direct contact with the researcher, or via colleagues at other primary health care centers in RÖC. We recruited only adult patients, >18 years, of both sexes with an earlier diagnosis of IBS. The patients were required to be fluent in Swedish and to have basic computer knowledge (i.e., able to operate a computer mouse). The GPs were recruited via e-mail that was sent to all 142 GPs in RÖC, and after two weeks, a reminder was sent again by e-mail.

To add further depth and understanding to the factor analysis, we performed brief interviews following the Q-sorting and three patients and three GPs were randomly selected for this interview, lasting approximately 20 min. We selected these participants before all analyses were performed. Hence, they do not necessarily represent all factors. We asked the participants to reflect on their most extreme rankings (see Supplementary Material 3). No standard questionnaire was used for these interviews. The interviewer made field notes that were read back to the participants for verification. The transcripts were not returned to the participants. The notes were anonymized, summarized and translated into English.

Ethical approval was granted by The Swedish Ethical Review Authority in Uppsala (2020-03098). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

We performed data analysis using the Q-methodology software. Factors for both the patient and GP groups were extracted by principal component analysis (PCA), which determined the factor loadings. The extracted factors were then rotated using the Varimax rotation method. The q-sorts for patient and GP groups were analyzed separately. Comparisons of the ranked statements were made both within patient and GP factors as well as between patients and GPs with emphasis on distinguishing statements. We identified statements of consensus and disagreement by analyzing their ranks and z-scores.

Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed using the statistical software SPSS (Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) to assess the relationships of the Z-scores from all statements between both groups.

Results

The patients had a mean age of 40.3 years and had a self-reported duration of IBS-related symptoms of an average of 16.9 years. All GPs had at least five years of experience in general practice (mean of 10.9 years) and a mean age of 48.6 years at the time of participation. Descriptions of the demographics for each factor are listed in and .

Table 1. Demographic data for patient factors.

Table 2. Demographic data for GP factors.

Three factors were extracted from both patient and GP groups. Six factors from both groups had eigenvalues > 1.0, which is a standard requirement for selecting factors in Q-methodology [Citation16]. However, a visual inspection of the scree plot revealed that the slope levelled off after factor 3 for both groups. The first 3 factors explained 54% and 57% of the total variance of the q-sorts, respectively and additional factors would not have contributed further to the analysis. Eigenvalues and percentages of explained variance are listed in .

Table 3. Eigenvalues and explained variances (%) of the top three factors.

Each factor was named after its most distinguishing statements and was considered a representation of a general viewpoint. Distinguishing statements as well as their rank scores are shown in supplementary material, and . Factors with their most agreed and disagreed statements are shown in supplementary material, and with their respective Z-scores.

Table 4. Pearson’s correlation coefficients (rs) and p-values between the GPs and patients’ Z-scores.

Pearson’s correlation analysis for the Z-scores showed a strong association between Patient Factor 1 and GP Factor 1 (r = 0.818, P= <0.001). The correlations between the factors are displayed in .

Patient factor 1 – ‘question the diagnosis of IBS’

Thirteen patients (5 male and 8 female) were loaded onto this factor. They seemed to question the diagnosis of IBS as the most distinguishing factor was ‘an IBS diagnosis is made when doctors do not know what is wrong’. They also seemed to believe that IBS is an umbrella term for different unknown conditions and that their symptoms may be caused by something yet to be discovered. One patient said:

“I do not think we know everything about what affects IBS, such as artificial substances that in the future will prove to be contributing to IBS symptoms.”

“I do not think an unhealthy lifestyle is the trigger. IBS affects how you feel, and it is difficult to live a healthy life when you cannot eat what you want or exercise. It affects you negatively when you are not in balance. This will probably lead to a vicious cycle.”

Patient factor 2 – ‘lifestyle changes for a physical disorder’

One male and 8 female patients belonged to this factor which had the lowest average age. They strongly believed in lifestyle changes for IBS and highlighted the importance of diet. The latter statement was most distinguishing in this group. They also recognized that exercise might play a role. These patients also believed that IBS is primarily a physical and not a psychological problem, although patients with IBS may be more prone to depression. Furthermore, they thought that IBS can lead to increased stress. One patient said:

“Anxiety and stress can have an influence. I guess I can only speak for myself and I do not think I have a mental illness. I think it is a defect in the bowels and that stress and anxiety can affect the symptoms.”

This group disagreed most with ‘knowing what causes IBS is not as important as being able to treat symptoms’.

Patient factor 3 – ‘importance of a diagnosis’

This factor included 8 female patients and no males. It had the highest average age (51.8 years) and the longest average duration of symptoms (25.1 years). These patients underlined the importance of a diagnosis and believed IBS is related to abnormal gastrointestinal motility. One patient stated:

“I believe the bowels are not working properly. Sometimes it feels like too much gas is formed and my intestines cannot stand anything.”

GP factor 1 – ‘unknown causes of great suffering’

This factor included 14 doctors and had a perfectly even gender distribution. These doctors believed that there are multiple causes of IBS that have yet to be discovered and that IBS is an umbrella term for many unknown conditions. There was also consensus about IBS being caused by bowel hypersensitivity and excessive gas production. One GP said:

“I am completely convinced that it is because the bowel does not move optimally and causes a lot of unpleasant symptoms. It is a shame that it has not yet been possible to clarify the exact mechanisms and develop an effective treatment. On the other hand, I am not sure if it will ever be possible to clarify completely.”

“I realize we are dealing with great suffering. Patients say they change their eating habits, need to be close to a toilet, cannot leave the house when they want, etc.”

GP factor 2 – ‘lifestyle changes are important, stress makes IBS worse’

This factor included 1 male and 7 female GPs. These doctors agreed that pressure or stress makes IBS worse and that lifestyle factors, including a person’s diet, play an important part. One GP stated:

“I think regular habits and controlled food intake usually make a difference. Additionally, it is important to determine what usually makes the problems worse. Regarding the diet, you can try to figure out what makes you feel good and what makes you feel worse. Treatment of psychosocial issues may also be beneficial.”

GP factor 3 – ‘recognized the way IBS affects patients’

Eight doctors (6 male and 2 female) were loaded onto this factor. They had slightly less experience within primary care (mean of 9.9 years) compared with the other two factors. They believed strongly that IBS has a significant negative impact on peoplés lives. One GP said:

“I think they adapt themselves or limit themselves in everyday life.”

Comparison between patient factors

Factor 1 had the most even gender distribution with 5 male and 8 female participants whereas factor 3 consisted entirely of females. Factor 3 also stood out with the oldest participants and with the longest self-reported duration of IBS-related symptoms.

Most patients seemed to believe that IBS is a physical and not a psychological disorder, although Factors 1 and 2 agreed that patients with IBS might be more likely to develop depression. They also agreed that lifestyle changes can be beneficial in the management of IBS, but opinions regarding exercise differed somewhat. Patients belonging to Factor 1 seemed to be most mistrustful of doctors regarding IBS diagnosis, whereas patients belonging to Factors 2 and 3 were more positive. Patients from Factor 1 also questioned the attitude of their physicians. To some extent, all patients shared the viewpoint that IBS is caused by something unknown to medical science.

Patients belonging to Factors 1 and 2 believed that being treated for any disease within health care can contribute to the development of IBS, but patients from Factor 3 disagreed quite strongly. Patients belonging to Factors 1 and 3 agreed that it is not as important to know the cause of IBS as being able to treat symptoms, whereas patients from Factor 2 disagreed strongly with this statement.

Patients belonging to Factor 1 did not believe in gender differences regarding IBS, but there was no clear consensus among other factors. Patients from Factors 1 and 3 firmly believed that a person’s cultural background has little to do with IBS, whereas patients from Factor 2 were more open to this viewpoint.

Comparison between GP factors

GP factor 1 had an even gender distribution, factor 2 was dominated by females whereas the opposite was true for factor 3. Mean age and mean years of experience within primary care were fairly similar between all factors.

There was a consensus that IBS greatly impacts their patients’ lives, causing much suffering. They all agreed that lifestyle changes as well as antidepressants may be beneficial for patients with IBS. They also believed that IBS might be caused by a disturbance of gut microbiota, gastrointestinal hypersensitivity, and excessive gas production.

GPs belonging to Factor 1 believed strongly that there is a proper medical cause for IBS that has not yet been discovered and that IBS is a collective term for different undefined conditions, whereas GPs from Factor 2 disagreed with both statements. GPs belonging to Factors 1 and 2 believed that inflammation could cause IBS, but GPs from Factor 3 disagreed.

Most GPs also believed that IBS is not a psychological condition, but GPs belonging to Factor 2 recognized that there may be psychological causes. Factors 2 and 3 agreed that worry can trigger IBS, while Factor 1 disagreed.

Self-critical opinions were scarce among GPs other than a slight uncertainty regarding diagnostic abilities among doctors in GP Factor 3.

GPs from Factor 1 did not believe that gender or cultural background play a significant role in IBS, while the other GPs agreed that there may be differences.

Discussion

Mutual understanding between patients and doctors is vital to properly manage most conditions. In this study viewpoints on IBS varied within patients and GPs as well as between the two groups, and there seemed to be a consensus among patients that IBS is primarily a physical and not a psychological disorder, which is a more consistent opinion compared with previous findings of diverse perceptions [Citation11]. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, GPs shared this opinion, in contrast to a previous study where GPs considered IBS mainly as a psychological disorder [Citation12]. Current knowledge suggests bidirectional dysregulation of the gut-brain axis, and it is not clear whether psychological factors drive the development of IBS or if they are secondary to gastrointestinal symptoms [Citation17]. There is also a well-documented benefit of cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with IBS with improvement of symptoms as well as quality of life [Citation18].

To some extent, patients and GPs also shared the opinion that doctors tend to see IBS as a psychological problem only because they do not know the cause (patient factor 1 and GP factor 1). Patients belonging to Factor 1 not only questioned the diagnostic abilities of their GPs but also their attitudes whereas most GPs did not agree with these types of statements. This is consistent with a previous study that showed that most patients have mainly negative perceptions of their health care providers, highlighting the need for empathy and patient education [Citation7].

Patients and GPs had the same perception that IBS prevents people from leading the lives they would like to lead. This was actually one of the highest-ranked distinguishing statements among GPs and one of the statements patients agreed on the most. Even though IBS is a benign condition, it is important to consider how much it impacts the quality of life. However, according to a previous study, GPs are not fully aware of how much IBS affects the lives of their patients [Citation8]. In some aspects, patients with IBS may experience a significantly lower health-related quality of life than patients with diabetes mellitus or even end-stage renal disease [Citation19].

Many patients believed their symptoms may be caused by inflammation and perhaps they may confuse IBS with inflammatory bowel disease. They also believed that IBS is an umbrella term for different unknown conditions, which is in line with the perception that GPs shared about IBS as a condition that may have multiple causes that have yet to be discovered. Both patients and GPs agreed that IBS might be caused by a disturbance of gut microbiota. GPs also believed that IBS may be caused by gastrointestinal hypersensitivity, and excessive gas production. In a previous study, GPs expressed uncertainty regarding the etiology of IBS [Citation12]. While the exact pathological mechanisms of IBS have not been elucidated, it is well established that IBS is caused by an alteration in brain-gut interaction, leading to gastrointestinal motility disturbances and visceral hypersensitivity [Citation20]. With the increased easy access to medical information online, at least in developed countries, patients are probably more educated than ever before but may also have trouble finding credible sources. This can be challenging for many GPs, as informed patients may want to participate in decision-making while lacking formal medical training [Citation21]. This emphasizes not only the importance of GPs being up-to-date on the latest medical knowledge but also the need for investing in a good patient-doctor relationship.

Patients believed in lifestyle changes, suggesting that most patients want to take responsibility for their physical health and do what they can to decrease symptoms of IBS. GPs also agreed, since there are well-known benefits to e.g. a low fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) diet, as well as physical exercise [Citation22,Citation23]. This should encourage GPs to continue recommending non-pharmacological treatment options for patients with IBS.

There was consensus between patient Factor 1 and GP Factor 1 that gender does not play a role in IBS, which is inconsistent with previous epidemiological findings of a higher prevalence of IBS among women [Citation1]. There were conflicting opinions regarding cultural issues, although these opinions did not truly stand out. Cultural issues may be regarded as a sensitive topic that is not always taken into consideration, but it is known that cross-cultural factors certainly play a part in functional gastrointestinal disorders [Citation24]. Among the participants, there was no support for religious faith in the management of this disorder, which is probably a reflection of the secularized Swedish society [Citation25].

Patients were either neutral or negative toward treatment with antidepressants, which may be explained by their perception of IBS as a somatic disorder. GPs agreed that antidepressants can improve symptoms of IBS, perhaps because of their knowledge of the broader indications of these types of medications. The positive effect of antidepressants in the treatment of IBS has been well established in previous studies [Citation26]. In fact, a recent study strongly supports the use of low-dose tricyclic antidepressants as a second-line therapy for patients with IBS [Citation27]. Possibly, there is still a stigma associated with antidepressants in combination with a lack of awareness of current evidence among patients with IBS.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of Q-methodology is that it allows for quantitative analysis of qualitative data and quantitative correlation analysis between groups, which provides an additional depth to the understanding of subjective opinions from, for example, patients and health care providers. Q-methodology also has limitations. Selection bias may be an issue but is not limited to this research method. GPs with a special interest in IBS or patient-doctor relations may have been more interested to participate. Patients with a more positive or negative view of healthcare providers may also have been more interested to participate. Patients who are reluctant to use computers, patients with certain cultural backgrounds, or those unsure of their language skills may have opted out. Factors such as intellectual functions, socioeconomic status, and previous knowledge of IBS may have further impacted the results. In addition, we do not know how many of the GPs had IBS. External validity is limited in q-methodology, which is why it is difficult to compare results from two groups from different studies regarding the same issue. Two previous q-methodology studies covering the same topic were performed by different researchers almost two decades apart in Great Britain [Citation11, Citation12]. One of the strengths of the present study is the direct comparison of two groups within the same setting.

In this study, there was female dominance among patients but a more even gender distribution among GPs, which may have influenced the results, especially regarding some statements that involved gender issues. There were also gender differences between factors, e.g. patient factor 3 consisted entirely of females. The relatively long average symptom duration among patients might also be a factor that should be taken into consideration since newly diagnosed patients might have less knowledge about IBS. We did not collect data on primary complaint or severity of symptoms which could also have added another depth to the study.

In summary, most patients and doctors view IBS as a physical disorder of unknown etiology with multiple possible explanations that causes a great deal of suffering with a significant impact on patients’ lives. They believe in the positive effects of lifestyle changes. There was some disagreement about gender and cultural factors. Some patients were critical regarding the attitudes and diagnostic abilities of their physicians, but there were also patients with a more positive outlook. Patients and GPs disagreed on the role of antidepressants in IBS treatment. Awareness of the differences in viewpoints regarding IBS is relevant for clinical practice. Clear and open communication about patients’ expectations in relation to the possible causes of their symptoms as well as the management of IBS is imperative for a constructive and mutually respectful patient-doctor relationship. It may also be key to finding a more individually suited therapeutic approach.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (37.4 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6(6):71–80. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S40245.

- Schmulson MJ, Drossman DA. What is new in rome IV. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;23(2):151–163. doi:10.5056/jnm16214.

- Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313(9):949–958. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.0954.

- Holtmann GJ, Ford AC, Talley NJ. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1(2):133–146. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30023-1.

- Bertram S, Kurland M, Lydick E, et al. The patient’s perspective of irritable bowel syndrome. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(6):521–525.

- Drossman DA, Chang L, Schneck S, et al. A focus group assessment of patient perspectives on irritable bowel syndrome and illness severity. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(7):1532–1541. doi:10.1007/s10620-009-0792-6.

- Halpert A, Godena E. Irritable bowel syndrome patients’ perspectives on their relationships with healthcare providers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(7-8):823–830. doi:10.3109/00365521.2011.574729.

- Casiday RE, Hungin AP, Cornford CS, et al. GPs’ explanatory models for irritable bowel syndrome: a mismatch with patient models? Fam Pract. 2009;26(1):34–39. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmn088.

- Millar JD, Mason H, Kidd L. What is Q-methodology? Evid Based Nurs. 2022;25(3):77–78. doi:10.1136/ebnurs-2022-103568.

- Churruca K, Ludlow K, Wu W, et al. A scoping review of Q-methodology in healthcare research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):125.

- Stenner PH, Dancey CP, Watts S. The understanding of their illness amongst people with irritable bowel syndrome: a Q-methodological study. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(3):439–452. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00475-x.

- Bradley S, Alderson S, Ford AC, et al. General practitioners’ perceptions of irritable bowel syndrome: a Q-Methodological study. Fam Pract. 2018;35(1):74–79. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmx053.

- Damio SM. Q methodology: an overview and steps to implementation. Asian J Univ Educ. 2016;12(1):105–122.

- Valenta AL, Wigger U. Q-methodology: definition and application in health care informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 1997;4(6):501–510. doi:10.1136/jamia.1997.0040501.

- Brown SR. A primer on Q methodology. osub. 1993;16(3/4):91–138. doi:10.22488/okstate.93.100504.

- Watts S, Stenner P. Doing Q methodology: theory, method and interpretation. Qual Res Psychol. 2005;2(1):67–91. doi:10.1191/1478088705qp022oa.

- Black CJ, Drossman DA, Talley NJ, et al. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: advances in understanding and management. Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1664–1674. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32115-2.

- Kisinger SW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome: current insights. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2017;19(10):231–237.

- Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, et al. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(3):654–660. doi:10.1053/gast.2000.16484.

- Ford AC, Sperber AD, Corsetti M, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 2020;396(10263):1675–1688. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31548-8.

- Terrero Ledesma NE, Nájera A, Reolid-Martínez RE, et al. Internet health information seeking by primary care patients. Rural Remote Health. 2022;22(4):6585. doi:10.22605/RRH6585.

- Van Lanen A-S, de Bree A, Greyling A. Efficacy of a low-FODMAP diet in adult irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60(6):3523–3523. doi:10.1007/s00394-021-02620-1.

- Johannesson E, Simrén M, Strid H, et al. Physical activity improves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(5):915–922. doi:10.1038/ajg.2010.480.

- Fang X, Francisconi CF, Fukudo S, et al. Multicultural aspects in functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs). Gastroenterology. 2016;15(6):1344–1354.

- Jänterä-Jareborg M.Jr Religion and the secular state: national report of Sweden. In: Martínez-Torron J, Cole Durham W, Thayer DT, editors. Religion and the secular state: national reports prepared on the occasion of the 18th congress of the international academy of comparative law. Madrid: Universidad de Complutense; 2015. p. 2–31.

- Ford AC, Lacy BE, Harris LA, et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(1):21–39. doi:10.1038/s41395-018-0222-5.

- Ford AC, Wright-Hughes A, Alderson SL, et al. Amitriptyline at low-Dose and titrated for irritable bowel syndrome as Second-Line treatment in primary care (ATLANTIS): a randomised, double-blind, placebocontrolled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;402(10414):1773–1785. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01523-4.