Abstract

Background

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is recognized by symptoms of heartburn and acid regurgitation. These gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms (GORS) are common in adults, but data from adolescents are sparse. This study aimed to assess the prevalence and risk factors of GORS among adolescents in a large and unselected population.

Methods

This study was based on the Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT), a longitudinal series of population-based health surveys conducted in Nord-Trøndelag County, Norway. This study included data from Young-HUNT4 performed in 2017–2019, where all inhabitants aged 13–19 years were invited and 8066 (76.0%) participated. The presence of GORS (any or frequent) during the past 12 months and tobacco smoking status were reported through self-administrated questionnaires, whereas body mass index (BMI) was objectively measured.

Results

Among 7620 participating adolescents reporting on the presence of GORS, the prevalence of any GORS and frequent GORS was 33.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] 32.2 − 34.3%) and 3.6% (95% CI 3.2 − 4.0%), respectively. The risk of frequent GORS was lower among boys compared to girls (OR 0.61; 95% CI 0.46 − 0.79), higher in current smokers compared to never smokers (OR 1.80; 95% CI 1.10 − 2.93) and higher among obese compared to underweight/normal weight adolescents (OR 2.50; 95% CI 1.70 − 3.66).

Conclusion

A considerable proportion of adolescents had GORS in this population-based study, particularly girls, tobacco smokers, and individuals with obesity, but frequent GORS was relatively uncommon. Measures to avoid tobacco smoking and obesity in adolescents may prevent GORS.

Introduction

In children, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is defined as present when ‘reflux of gastric contents is the cause of troublesome symptoms and/or complications’ [Citation1], which is in line with the Montreal definition of GORD in adults [Citation2]. The cardinal symptoms of GORD are heartburn and acid regurgitation [Citation3], which is reliably self-reported also among children and adolescents [Citation1]. Gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms (GORS) are associated with reduced quality of life and an increased risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in adults [Citation4].

According to systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the average global prevalence of GORD based on weekly frequency of heartburn or regurgitation in adults is 13–14%, but this varies greatly across geographic locations [Citation5,Citation6]. GORD is also common in adolescents, but the prevalence estimates are uncertain with a wide range due to sparse literature using different tools to assess GORD [Citation7,Citation8]. A French study from 2012 reported the prevalence of GORD among adolescents to be 7.6% [Citation8], and an Indonesian study from 2019 reported the prevalence of GORD among adolescents to range up to 32.9% [Citation7].

In adults, obesity and tobacco smoking are the main environmental risk factors of GORS [Citation9]. The literature on risk factors of GORS in adolescents is scarce as well, but obesity has been associated with GORS in a few studies [Citation10,Citation11], whereas smoking has not [Citation10]. In an Italian study, GORS was more frequent in obese children (61%) compared to normal weight children (22%) [Citation11]. In a British study, obesity increased the risk of acid regurgitation by 3.46 (95% CI 1.24 − 9.69). But smoking was not associated with acid regurgitation or heartburn [Citation10]. Identification of risk factors could identify areas that should be focused on in the prevention of GORS in adolescents.

The aims of this study were to assess the prevalence and risk factors of GORS in a large and unselected general adolescent population.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

The Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) is a population-based longitudinal series of health surveys conducted in Nord-Trøndelag County, Norway, since 1984 [Citation12–14]. It constitutes a large and unselected database for research and includes data from questionnaires, interviews, clinical measurements, and biological samples. Young-HUNT is the adolescent part of the HUNT studies. All inhabitants aged 13–19 years were invited to participate. Young-HUNT4 was conducted in 2017–2019 with 8066 participants (76.0% response rate).

Assessment of GORS

In the questionnaire, the participants were asked: ‘Have you had heartburn or acid regurgitation in the past 12 months?’ with the response alternatives: ‘Never’, ‘sometimes’, or ‘often’. In the analyses, those who reported ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’ were included in the category ‘any GORS’ and those who reported ‘often’ were included in the category ‘frequent GORS’.

Assessment of tobacco smoking

In the questionnaire, the participants were asked: ‘Have you ever tried smoking?’ with the response alternatives: ‘Yes’ and ‘no’ and: ‘Do you smoke?’ with the response alternatives: ‘No, I do not smoke’, ‘former occasional smoker’, ‘former daily smoker’, ‘occasional smoker’, and ‘daily smoker’. Three categories for tobacco smoking status were used: ‘Never smokers’, ‘previous smokers’, and ‘current smokers’. Never smokers included those who answered ‘no’ to ‘have you ever tried smoking?’, those who answered ‘yes’ to ‘have you ever tried smoking?’ but answered ‘no, I do not smoke’ and those who did not answer ‘have you ever tried smoking?’ but answered ‘no, I do not smoke’. Previous smokers consisted of those who answered ‘yes’ to ‘have you ever tried smoking?’ and then answered, ‘former occasional smoker’ or ‘former daily smoker’. Current smokers were those who answered ‘yes’ to ‘have you ever tried smoking?’ and then answered ‘occasional smoker’ or ‘daily smoker’. Finally, those who answered ‘yes’ to the first question ‘Have you ever tried smoking?’ but did not answer the second question ‘Do you smoke?’, were excluded from the analyses of tobacco smoking.

Assessment of body mass index

Height and weight were objectively measured by a bioimpedance machine (InBody 770). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). Age and sex-adjusted cut-offs for BMI for defining overweight and obesity in adolescents [Citation15] were used to subdivide BMI into the World Health Organization’s classification categories for BMI [Citation16]: ‘underweight/normal weight’, ‘overweight’, and ‘obesity’.

Statistical analyses

The prevalence with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of GORS was separately calculated as the proportion of participants who reported any GORS or frequent GORS, and the analyses were stratified by sex.

The risk of prevalent GORS was calculated by multivariable logistic regression, providing odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs, adjusted for sex, age (continuous), smoking (categorized into never smokers, previous smokers, and current smokers), and BMI (underweight/normal weight, overweight, and obesity). The p value for trend of the categorical BMI variable was assessed by the Wald test for linear trend.

Study approval

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, South East (#115969). All participants signed a written consent when they participated in the Young-HUNT study.

Results

Participants

The questions regarding GORS were completed by 7620 individuals who constituted the final study cohort (). The sex distribution was equal, and the mean age was 16.1 years (standard deviation 1.8). Only 5.3% were current smokers, the mean BMI was 22.2 (standard deviation 4.2), and 6.3% were obese.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants in the fourth young in Trøndelag Health study (Young-HUNT4) 2017–2019.

Prevalence of GORS

The overall prevalence of any GORS was 33.2% (95% CI 32.2 − 34.3%) and of frequent GORS 3.6% (95% CI 3.2 − 4.0%) for the adolescents. The prevalence of any GORS was similar between the sexes; 33.4% (95% CI 32.0 − 34.9%) among girls and 33.0% (95% CI 31.5 − 34.5%) among boys. The prevalence of frequent GORS was higher among girls than for boys; 4.3% (95% CI 3.7 − 5.0%) and 2.8% (95% CI 2.3 − 3.4%), respectively.

Risk factors for GORS

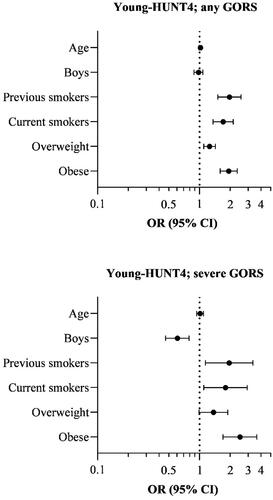

The risk of having GORS by age, sex, smoking, and obesity is presented in and . Age among the adolescents was not associated with GORS. The risk of any GORS was similar in girls and boys, but the risk of frequent GORS was lower among boys compared to girls (adjusted OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.46 − 0.79). Tobacco smoking was associated with an increased risk of GORS (adjusted OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.36 − 2.14 for any GORS and 1.80, 95% CI 1.10 − 2.93 for frequent GORS). Obesity also increased the risk of GORS (adjusted OR 1.93, 95% CI 1.60 − 2.34 for any GORS and 2.50, 95% CI 1.70 − 3.66 for frequent GORS). There was also a dose-response association between increasing BMI category and the risk of GORS (p for trend <0.001).

Figure 1. Risk of any and frequent gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms (GORS) in adolescents (13 − 19 years) in the fourth Young in Trøndelag Health Study (Young-HUNT4), adjusted for the other variables in the figures. Reference values: 13 years of age, girls, never smokers and under-/normal weight. OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval.

Table 2. The risk of any and frequent gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms (GORS) in the fourth young in Trøndelag Health study (Young-HUNT4).

Discussion

This study found that a third of adolescents aged 13 − 19 years had GORS. Boys had lower risk of frequent GORS than girls, and smoking and obesity increased the risk of both any and frequent GORS.

Strengths of the study include the population-based design of an unselected cohort with high participation rate and the large sample size allowing robust results and subgroup analyses. The HUNT study is representative for a Western European population. Limitations include lack of data on the use of antireflux medication. However, the vast majority of patients with GORD using medication still report GORS. The assessment of GORS was subjective, without any objective verification of GORD, and especially the group reporting GORS only ‘sometimes’ probably include individuals with other disorders than GORD. However, the association with smoking and obesity was still present in the group reporting only GORS ‘sometimes’. Moreover, the large majority of those reporting GORS ‘frequently’ are likely to have GORD, as defined by the consensus definition of GORD [Citation1] and as shown in our previous validation study [Citation17]. Other factors have also been associated with GORS, like symptoms of anxiety and depression, but data on these symptoms were not available and could not be assessed.

Previous studies that have investigated the prevalence of GORS/GORD in adolescents have used different definitions of GORD and various age ranges. A recent Indonesian study of 520 adolescents aged 12–18 years found a 32.9% prevalence of GORS using a GerdQ cut-off of ≥7 and 10.9% prevalence using a GerdQ cut-off of ≥8 [Citation7]. The GerdQ is a questionnaire about frequency of GORD-related symptoms in the past week, where a cut-off of ≥7 has been suggested for adolescents [Citation18]. This definition corresponds well with this study’s prevalence of any GORS. A Japanese study found a prevalence of GORD of 4.4% (GerdQ ≥8) among individuals aged 6 − 19 years (n = 341) [Citation19] i.e., results in line with the prevalence of frequent GORS in this study. A Taiwanese study conducted among students aged 13–16 years (n = 1745), reported a prevalence of acid reflux and heartburn of 9.4% [Citation20]. In a French study among children and adolescents (n = 10,394), the prevalence of GORD was 7.6% among those aged 12–17 years [Citation8], but GORD was broadly defined, including symptoms less specific for GORD. A US study of students aged 14–18 years (n = 1343) reported a prevalence of at least monthly heartburn and regurgitation of 22.4% and 21.4%, respectively, and at least weekly heartburn and regurgitation of 9.1% and 8.5%, respectively [Citation21]. In a study from Northern Ireland among adolescents aged 12–18 years (n = 1133), the prevalence of at least weekly heartburn and acid regurgitation was 3.2% and 5.1%, respectively [Citation10]. In a US study, conducted in paediatric practices (n = 615; aged 10–17 years), the prevalence of weekly heartburn and acid regurgitation was 5.2% and 8.2%, respectively [Citation22]. These results correspond well with the prevalence of GORS found in the current study. However, in a large study from Israel with data on 17-year-olds (n = 466,855), the prevalence of heartburn or acid regurgitation at least three times a week during three consecutive months was 0.18% [Citation23]. This was considerably lower than the prevalence of frequent GORS in the current study (and other studies) but could be explained by their strict definition of GORD. In summary, the studies that defined GORD as at least weekly symptoms of heartburn or acid regurgitation corresponded well with the prevalence of frequent GORS found in the current study. Except for the Israeli study, the prevalence of GORS among adolescents seems to be similar across different geographical areas.

Few studies have examined risk factors for GORS/GORD in adolescents. In a US case–control study with 236 cases and 101 controls, aged 7–16 years, the prevalence rate of a positive reflux score (≥3 on a scale from 0 to 10 of GORD symptoms in the past week) was not associated with age or sex [Citation24]. However, a positive reflux score was more frequent in obese children (13.1%) compared to the non-obese control group (2.0%) with an adjusted OR of 7.4 (95% CI 1.7–32.5). The reflux symptom score increased from 2.0% in the control group through 11.7% in obese children to 20% in severely obese children. In an Italian study (n = 153; aged 2–18 years), GORS was significantly more frequent in obese children compared to normal-weight children (61.3% vs. 21.8%) and a dose-response relation was suggested between increasing BMI and GORS [Citation11]. However, GORS included oesophageal symptoms not specific of GORD. A study conducted in Northern Ireland (n = 1133) among adolescents aged 12–18 years found a strong association between obesity and at least weekly acid regurgitation (OR 3.46; 95% CI 1.24–9.69), while no association was found between BMI and heartburn [Citation10]. In the Israeli study of 17-year-olds (n = 466,855), higher BMI was associated with higher prevalence rates of GORD [Citation23]. A large cross-sectional study from the US (n = 690,321; aged 2–19 years), where data were obtained from medical records reported that moderate obesity (BMI ≥ 30) (OR 1.16; 95% CI 1.07–1.25) and extreme obesity (BMI ≥ 35) (OR 1.40; 95% CI 1.28–1.52) was associated with GORD among adolescents aged 12–19 years [Citation25]. In agreement with these previous studies, the current study identified obesity and overweight as risk factors for GORS. In contrast to this, the study from Northern Ireland found no associated with neither acid regurgitation nor heartburn and smoking [Citation10].

The current study and previous studies show that GORS are highly prevalent among adolescents. As GORS reduce health related quality of life and increases the risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in adults, GORS should be prevented and treated in adolescents. Especially measures to avoid smoking and obesity in adolescents are warranted.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this large and population-based cohort study found that a considerable proportion of adolescents suffered from GORS. Boys had reduced risk of GORS compared to girls, and the exposure to tobacco smoking and obesity increased the risk of GORS in the adolescents.

Author contributions

Mrs. Ellen Sylvia Visnes conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Mr. Andreas Hallan, Dr. Maria Bomme, Dr. Dag Holmberg, Dr. Jane Møller-Hansen, and Dr. Jesper Lagergren critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Dr. Eivind Ness-Jensen conceptualized and designed the study, supervised the analyses, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

| Abbreviations | ||

| BMI: | = | body mass index |

| CI: | = | confidence interval |

| GORD: | = | gastro-oesophageal reflux disease |

| GORS: | = | gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms |

| HUNT: | = | Trøndelag Health Study |

| OR: | = | odds ratio |

| US: | = | United States |

Acknowledgments

The Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) is a collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology NTNU), Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Regional Health Authority, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data is available through application to HUNT Research Centre: https://hunt-db.medisin.ntnu.no/hunt-db/#/

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sherman PM, Hassall E, Fagundes-Neto U, et al. A global, evidence-based consensus on the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the pediatric population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(5):1278–1295; quiz 1296. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.129.

- Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et al. The montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(8):1900–1920; quiz 1943. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x.

- Klauser AG, Schindlbeck NE, Müller-Lissner SA. Symptoms in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 1990;335(8683):205–208. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90287-f.

- Wiklund I, Carlsson J, Vakil N. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and well-being in a random sample of the general population of a swedish community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(1):18–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00343.x.

- Eusebi LH, Ratnakumaran R, Yuan Y, et al. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2018;67(3):430–440. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313589.

- Nirwan JS, Hasan SS, Babar ZU, et al. Global prevalence and risk factors of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD): systematic review with meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5814. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62795-1.

- Artanti D, Hegar B, Kaswandani N, et al. The gastroesophageal reflux disease questionnaire in adolescents: what Is the best cutoff score? Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2019;22(4):341–349. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2019.22.4.341.

- Martigne L, Delaage PH, Thomas-Delecourt F, et al. Prevalence and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children and adolescents: a nationwide cross-sectional observational study. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171(12):1767–1773. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1807-4.

- Hallan A, Bomme M, Hveem K, et al. Risk factors on the development of new-onset gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. A population-based prospective cohort study: the HUNT study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(3):393–400; quiz 401. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.18.

- Murray LJ, McCarron P, McCorry RB, et al. Prevalence of epigastric pain, heartburn and acid regurgitation in adolescents and their parents: evidence for intergenerational association. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19(4):297–303. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32802bf7c1.

- Quitadamo P, Buonavolontà R, Miele E, et al. Total and abdominal obesity are risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55(1):72–75. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182549c44.

- Åsvold BO, Langhammer A, Rehn TA, et al. Cohort profile update: the HUNT study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2023;52(1):e80–e91. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyac095.

- Åsvold BO, Langhammer A, Rehn TA, et al. Cohort profile: the HUNT study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;52(1):e80–e91. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyac095.

- Holmen TL, Bratberg G, Krokstad S, et al. Cohort profile of the Young-HUNT study, Norway: a population-based study of adolescents. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):536–544. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys232.

- Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, et al. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320(7244):1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240.

- Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i-xii1–253.

- Ness-Jensen E, Lindam A, Lagergren J, et al. Changes in prevalence, incidence and spontaneous loss of gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a prospective population-based cohort study, the HUNT study. Gut. 2012;61(10):1390–1397. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300715.

- Chiu JY, Wu JF, Ni YH. Correlation between gastroesophageal reflux disease questionnaire and erosive esophagitis in school-aged children receiving endoscopy. Pediatr Neonatol. 2014;55(6):439–443. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2014.01.004.

- Okimoto E, Ishimura N, Morito Y, et al. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children, adults, and elderly in the same community. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(7):1140–1146. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12899.

- Chen JH, Wang HY, Lin HH, et al. Prevalence and determinants of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in adolescents. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(2):269–275. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12330.

- Gunasekaran TS, Dahlberg M, Ramesh P, et al. Prevalence and associated features of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in a caucasian-predominant adolescent school population. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(9):2373–2379. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-0150-5.

- Nelson SP, Chen EH, Syniar GM, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during childhood: a pediatric practice-based survey. Pediatric practice research group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(2):150–154. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.2.150.

- Landau DA, Goldberg A, Levi Z, et al. The prevalence of gastrointestinal diseases in israeli adolescents and its association with body mass index, gender, and jewish ethnicity. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(8):903–909. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31814685f9.

- Pashankar DS, Corbin Z, Shah SK, et al. Increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in obese children evaluated in an academic medical center. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(5):410–413. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181705ce9.

- Koebnick C, Getahun D, Smith N, et al. Extreme childhood obesity is associated with increased risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease in a large population-based study. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(2–2):e257-63–e263. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.491118.