Abstract

Background

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is increasing. The prevalence of overweight and obesity is increasing in parallel with IBD and could contribute to IBD development. The aim of this study was to assess the relationship between weight change and the risk for IBD.

Methods

Data gathered from 55,896 adult participants in the three first population-based Trøndelag Health Studies (HUNT1-3), Norway, performed in 1984–2008 was used. The exposure was change in body mass index between two HUNT studies. The outcome was a new IBD diagnosis recorded during a ten-year follow-up period after the exposure assessment. The risk of IBD by weight change was assessed by Cox regression analyses reporting hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusted for sex, age, and smoking status.

Results

There were 334 new cases of ulcerative colitis (UC) and 54 of Crohn’s disease (CD). Weight loss decreased the risk of a new UC diagnosis by 38% (adjusted HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.39–0.97) and seemed to double the risk of getting a new CD diagnosis (adjusted HR 2.01, 95% CI 0.91–4.46). Weight gain was not associated with a new diagnosis of neither UC (adjusted HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.78–1.26) nor CD (adjusted HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.56–2.08).

Conclusion

In this study, weight loss was associated with decreased risk of UC. However, no associations were seen between weight gain and the risk of UC or CD, suggesting that the increasing weight in the general population cannot explain the increasing incidence of IBD.

Introduction

The incidence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is increasing worldwide, mostly in westernized countries. A systematic review published in 2011 found the highest prevalence and annual incidence of IBD in Europe and thereafter North America. In Europe, the prevalence of ulcerative colitis (UC) was 505 and of Crohn’s disease (CD) 322 per 100,000 persons and the annual incidence of UC 24.3 and of CD 12.7 per 100,000 person-years [Citation1]. A substantial rise in the prevalence of IBD is predicted as more countries westernize [Citation2].

The exact cause of IBD is unknown, but both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the development. Alterations in the gut microbiome and dysfunctions of both the innate and adaptive immune system are suggested to play a role [Citation3]. Over 230 risk alleles for IBD are identified in large genome-wide association studies [Citation4]. Smoking is well documented for being protective of UC, while increasing the risk for CD. Many other environmental risk factors are suggested, including childhood hygiene, previous infections, diet, appendectomy, breastfeeding, stress, and different drugs as oral contraceptives, non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, and antibiotics. However, studies show inconsistent findings for most environmental risk factors and more research is necessary [Citation5].

A meta-analysis from 2021 of five larger cohorts concluded that obesity is associated with an increased risk of CD, but not for UC6. Studies have also found a link between obesity and other autoimmune diseases, like rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis [Citation6, Citation7]. Obesity is increasingly seen as a state of low-grade inflammation [Citation8], and a study showed that obesity is associated with increased levels of fecal calprotectin, a marker of bowel inflammation [Citation9]. Another study found an association between obesity and increased zonulin levels, a marker of intestinal permeability [Citation10].

There is an increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in the world’s population [Citation11]. In 2016, WHO published that more than 39% of the adult population is overweight and 13% obese [Citation11]. Contrary to conventional beliefs that patients with IBD are malnourished, cross-sectional studies show that about 15–40% of adults with IBD are obese, and an additional 20–40% are overweight [Citation12].

While it is reasonable to believe that obesity can contribute to IBD development, few studies have assessed weight change itself. The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) II, found that weight gain was associated with increased risk of CD, but not for UC, while weight loss did not affect the risk of neither UC nor CD14.

The aim of the present study was to further investigate the relationship between weight change and a new IBD diagnosis in a large prospective cohort study.

Materials and methods

The present study is based on the Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT), a large population-based prospective cohort study of the inhabitants of Nord-Trøndelag County, Norway [Citation13]. Every inhabitant in the county above 20 years of age were invited to participate in the study. The HUNT study includes questionnaires, interviews, clinical measurements, and biological samples. Data was gathered from individuals with repeated participation in the three first studies: HUNT1 performed 1984–86, HUNT2 performed 1995–1997, and HUNT3 performed 2006–2008.

Exposure

The exposure was the participants’ change in body mass index (BMI) between two HUNT studies. BMI at each HUNT study was calculated based on the participants objectively and standardized measured weight and height. Weight was measured with the participants wearing light clothes without shoes, and the result was rounded down to the nearest half kilo. Height was measured without shoes, and the result was given in whole centimeters. Those who did not participate in these clinical measurements were excluded from the study.

Outcome

All information from the HUNT studies was linked to the Norwegian 11-digit personal identification number, which again allowed HUNT data to be linked to hospital records. The vast majority of specialist health care in the HUNT population is done at the hospitals in Levanger, Namsos, and Trondheim (St. Olav’s Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital) and data on IBD diagnoses was collected from these hospitals.

Information on the diagnoses was collected from the hospital records from September 1987 to August 2021. The ICD9 code 556 and ICD10 code K51 were used to identify UC and the ICD9 code 555 and the ICD10 code K50 were used to identify CD. In addition, ICD9 558.9 and ICD10 K52.3 were used to identify undetermined colitis. The IBD diagnosis was only included if the patient had at least two IBD diagnoses registered at different occasions. This was done to reduce the number of misclassified cases, a validated approach in similar population-based cohorts [Citation14]. In the data analysis, the time point of the first IBD diagnosis and the last given diagnosis code were used. Patients with an IBD diagnosis before participation in the HUNT second/follow-up study were excluded from the present study.

Confounders

These possible confounding factors were considered: sex, age, and smoking status. Data on sex and age were collected from the National Population Register.

Information on smoking status was collected from self-reported questionnaires. In HUNT1 and HUNT2, the participants responded with the following alternatives: never smoked daily, ex-smoker daily, and current smoker daily. In HUNT3, the response alternatives were: never smoked, ex-smoker, daily smoker, and occasional smoker.

Statistical analyses

The weight change was calculated by the difference in BMI between HUNT1 and HUNT2 or between HUNT2 and HUNT3. Only the weight change between HUNT2 and HUNT3 was used for those who participated in all three studies. The exception was if the participant had missing value for BMI in HUNT3, but not in HUNT1 and HUNT2. In that case, the analysis was based on the weight change between the two first HUNT studies.

Based on the change in BMI, the participants were divided into the following groups: change in BMI by ≤1 kg/m2 (reference group), increase in BMI by >1 kg/m2 and decrease in BMI by >1 kg/m2. A new IBD diagnosis was recorded within 10 years after participation in the second/follow-up HUNT study.

Smoking status was divided into three groups: current (daily, occasional), previous, or never smokers.

The risk of IBD after weight change was assessed by Cox multivariable proportional hazard regression, adjusted for the confounding factors, reporting hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence interval (CIs). The analysis was conducted with UC and CD as separate outcomes. The data management and analyses were performed with Stata/MP 17.0 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical approval and consent

The study was ethically approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research, Central (#237971). All participants gave a written informed consent when participating in the HUNT study, including approval of linkage of data to hospital records.

Results

Selection and characteristics of the study population

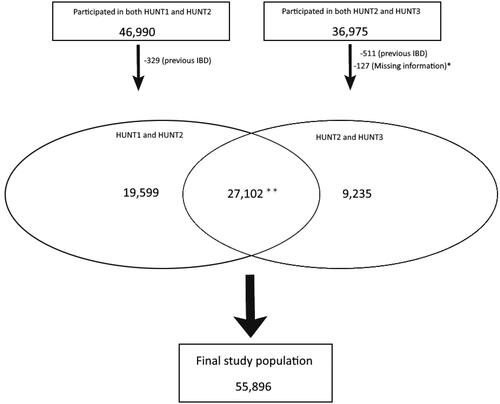

The selection of the study population is shown in . The final study population was 55,896 participants. The characteristics of the study participants are shown in . The percentage of women in the study sample was 54.0% and the median age at the follow-up HUNT study was 60.4 years. Furthermore, 38.9% reported never having smoked, 32.3% had smoked previously, and 24.8% were current smokers at the second/follow-up study. At baseline, the median BMI was 25.6 kg/m2, while 26.8 kg/m2 in the follow-up study. The percentage of obesity increased from 14.2% to 23.0% between baseline and follow-up. In total, there were 388 new cases of IBD during the ten years follow-up period, in which 334 cases were UC and 54 cases CD.

Figure 1. The selection of the final study population included participants with follow-up between HUNT1 and HUNT2 (left side) or HUNT2 and HUNT3 (right side), respectively. Participants with a previous inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) diagnosis were excluded.*The participants were excluded because of missing values on BMI in HUNT3. **Data from the two latest HUNT studies was used when there were observations from all three HUNT studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study participants.

Risk of IBD

Weight loss decreased the risk of a new UC diagnosis (adjusted HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.39 − 0.97) () and seemed to increase the risk of av new CD diagnoses (adjusted HR 2.01, 95% CI 0.91 − 4.46) (). Weight gain was not associated with a new UC (adjusted HR 1.00, 95% 0.78 − 1.26) () or CD diagnosis (adjusted HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.56 − 2.08) (). Similar results were for also found for the subgroups that were normal weight, overweight, and obese at baseline (results not shown), but this could not be assessed in the subgroup that were underweight at baseline due to few participants and few new IBD cases in this subgroup.

Table 2. The risk of a new UC diagnosis after change in BMI (kg/m2).

Table 3. The risk of a new CD diagnosis after change in BMI (kg/m2).

Discussion

In this population-based prospective cohort study, weight loss was associated with decreased risk of a new UC diagnosis and possibly an increased risk of a new CD diagnosis. However, weight gain was not associated with neither a new UC nor CD diagnosis.

Most previous studies on the relationship between weight and IBD look at absolute BMI categories and not the change in BMI itself. In 2021, a meta-analysis of five larger cohorts was conducted to assess obesity and the risk of IBD. In total there were 601,009 participants with 10,110,018 person-years of follow up and 1047 new cases of UC and 563 new cases of CD. The pooled analysis concluded that obesity is associated with an increased risk of CD (adjusted HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.05–1.71), but not for UC (adjusted HR 0.88, 95% CI 0.72–1.08). However, the pooled analysis did not include weight change, as compared to the present study [Citation15]. The only other larger study that assessed weight change and the risk for IBD with a prospective cohort design is the NHS II.

The NHS II began in 1989 and followed 111,498 US female nurses (median age 35 years) for over 18 years, including 229 new cases of UC and 153 of CD based on self-reported questionnaires. The study found that weight gain was associated with increased risk of CD (adjusted HR 1.52, 95% CI 0.87–2.65), but not for UC (adjusted HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.60–1.40). Furthermore, weight loss did not affect the risk of neither UC nor CD. These results differ from the present study. However, the NHS II included self-reported data only, which reduces validity and was not representative for men [Citation16].

A strength of the present study is the prospective cohort design, with assessment of the exposure before the outcome. This population-based design also minimizes the risk for selection bias. Furthermore, the study sample included both women and men, and all adults from the age of 20 and above. However, as the median age at the HUNT follow up study was 60.4 years, the studied population is mostly representative for late-onset IBD. The height and weight were measured objectively and standardized, assuring their reliability. In addition, the study was adjusted for the important confounders sex, age, and smoking status. For patients with both an UC and CD diagnosis, only the last diagnosis given was used. This increased the probability for a correct diagnosis as some might have been misdiagnosed initially.

There were also a few limitations in this study. The study is based on a population-based sample of adults above 20 years of age, so it is not representative of the pediatric and adolescent IBD population. The study had a high ratio of newly diagnosed UC to CD patients, which could partly be explained by the inclusion of participants above 20 years of age only and the high median age of the study population. The IBD diagnosis was based on diagnostic codes and not verified by hospital record searches. However, the risk of misclassification was reduced by only including patients with at least two IBD diagnoses registered at different occasions. Undiagnosed IBD could have contributed to weight loss, as this is a common symptom of IBD, challenging causality. However, the reduced risk of a new UC diagnosis with weight loss, cannot be explained by this. Another issue with this study was the small sample size with few new IBD cases, which reduced the accuracy of the estimated hazard ratios and increase the risk of type II statistical error, especially for CD. This could explain the statistically non-significant increased risk of a new CD diagnosis with weight loss. Furthermore, the study did not assess loss of follow-up. Some cases of IBD might have been lost as the hospital records were only acquired from the hospitals in Trøndelag County. However, the vast majority of specialist health care of the study population is performed within the county. Selection bias might have occurred as the patients diagnosed with IBD between the two HUNT studies (baseline and follow-up) were excluded. The participation rate in the HUNT study has dropped during the decades of follow-up, but the relatively high participation rate in this population-based setting still indicates a low concern for selection bias. However, it should be noted that the prevalence of chronic diseases is higher among the non-participants, and they have lower socioeconomic status and higher mortality than the participants [Citation13]. Lastly, other confounders like diet and physical activity were not accounted for, nor alternative reasons for weight changes such as pregnancy.

The present study suggests that the increasing weight in the general population cannot explain the parallel increase in IBD incidence. However, this result should be confirmed in other large prospective cohort studies from other populations before any conclusions can be made. The increasing incidence of IBD probably has multiple causes, both genetic and environmental, with complex interactions which need to be addressed in these future studies.

In conclusion, weight loss decreased the risk for a new diagnosis of UC and seemed to increase the risk of a new diagnosis of CD. However, no associations were seen for weight gain and UC or CD.

Authors’ contributions

MC, ENJ and AKS contributed to the study concept and design. MC and ENJ drafted the first manuscript. All authors have contributed to the interpretation of the data. All authors have contributed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) is a collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology NTNU), Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Regional Health Authority and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data is available through application to HUNT Research Centre: https://hunt-db.medisin.ntnu.no/hunt-db/#/

Additional information

Funding

References

- Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(1):46–54.e42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001.

- Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(12):720–727. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150.

- Zhang YZ, Li YY. Inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(1):91–99. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.91.

- Turpin W, Goethel A, Bedrani L, et al. Determinants of IBD heritability: genes, bugs, and more. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(6):1133–1148. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy085.

- Molodecky NA, Kaplan GG. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2010;6(5):339–346.

- Sterry W, Strober BE, Menter A, International Psoriasis Council. Obesity in psoriasis: the metabolic, clinical and therapeutic implications. Report of an interdisciplinary conference and review. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(4):649–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08068.x.

- Qin B, Yang M, Fu H, et al. Body mass index and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0601-x.

- Winer DA, Luck H, Tsai S, et al. The intestinal immune system in obesity and insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2016;23(3):413–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.01.003.

- Poullis A, Foster R, Shetty A, et al. Bowel inflammation as measured by fecal calprotectin: a link between lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(2):279–284. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-03-0160.

- Kim JH, Heo JS, Baek KS, et al. Zonulin level, a marker of intestinal permeability, is increased in association with liver enzymes in young adolescents. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;481:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.03.005.

- Obesity and overweight. Accessed September 4, 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Singh S, Dulai PS, Zarrinpar A, et al. Obesity in IBD: epidemiology, pathogenesis, disease course and treatment outcomes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(2):110–121. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.181.

- Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K, et al. Cohort profile: the HUNT study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):968–977. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys095.

- Jakobsson GL, Sternegård E, Olén O, et al. Validating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the swedish national patient register and the swedish quality register for IBD (SWIBREG). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(2):216–221. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1246605.

- Chan SSM, Chen Y, Casey K, et al. Obesity is associated with increased risk of crohn’s disease, but not ulcerative colitis: a pooled analysis of five prospective cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;20(5):1048–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.06.049.

- Khalili H, Ananthakrishnan AN, Konijeti GG, et al. Measures of obesity and risk of crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(2):361–368. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000283.