Abstract

Background and study aims

Long-time follow-up of sigmoidoscopy screening trials has shown reduced incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer (CRC), but inadequate bowel cleansing may hamper efficacy. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of bowel cleansing quality in sigmoidoscopy screening.

Patients and methods

Individuals 50 to 74 years old who had a screening sigmoidoscopy in a population-based Norwegian, randomized trial between 2012 and 2019, were included in this cross-sectional study. The bowel cleansing quality was categorised as excellent, good, partly poor, or poor. The effect of bowel cleansing quality on adenoma detection rate (ADR) and referral to colonoscopy was evaluated by fitting multivariable logistic regression models.

Results

35,710 individuals were included. The bowel cleansing at sigmoidoscopy was excellent in 20,934 (58.6%) individuals, good in 6580 (18.4%), partly poor in 7097 (19.9%) and poor in 1099 (3.1%). The corresponding ADRs were 17.0%, 16.6%, 14.5%, and 13.0%. Compared to participants with excellent bowel cleansing, those with poor bowel cleansing had an odds ratio for adenoma detection of 0.66 (95% confidence interval 0.55–0.79). We found substantial differences in the assessment of bowel cleansing quality among endoscopists.

Conclusions

Inadequate bowel cleansing reduces the efficacy of sigmoidoscopy screening, by lowering ADR. A validated rating scale and improved bowel preparation are needed to make sigmoidoscopy an appropriate screening method.

Trial registration Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 01538550)

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major health burden with more than 1.9 million annual new cases in 2020 worldwide [Citation1]. The most effective and efficient approach for CRC screening is still unknown and under continuous evaluation. Colonoscopy screening, a resource demanding examination, may be less effective in reducing CRC incidence and mortality than anticipated [Citation2]. Sigmoidoscopy screening may be less burdensome for participants and the healthcare system. Four large randomized controlled trials have shown that sigmoidoscopy screening reduces both CRC incidence and mortality through early cancer detection and removal of adenomas [Citation3–7].

The bowel cleansing quality is a key performance indicator (KPI) for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy [Citation8–12], affecting other KPIs like the adenoma detection rate (ADR) [Citation13–18], examination completeness [Citation18], patients’ experience [Citation19] and costs [Citation17,Citation20]. However, evidence is mainly derived from colonoscopy studies. The impact of inadequate bowel cleansing quality on the different KPIs in sigmoidoscopy has not been satisfactorily explored. Only two previous sigmoidoscopy screening trials have reported the association between ADR and bowel cleansing quality, both showing a positive association [Citation21,Citation22]. Good bowel cleansing quality facilitated the intubation of the splenic flexure during sigmoidoscopy in the English bowel screening programme and thus ensured an optimised ADR [Citation23].

We performed a cross-sectional study of more than 35,000 screening sigmoidoscopies to assess the impact of inadequate bowel cleansing quality on ADR, referral rates to work-up colonoscopy and some other KPIs. We used data from a population-based randomized clinical trial piloting a national CRC screening program in Norway comparing once-only sigmoidoscopy and a biennial faecal immunochemical test [Citation24].

Material and methods

Study design

Between 2012 and 2019, approximately 140,000 individuals aged 50–74 years, living in South-East Norway, were randomly invited, in a 1:1 ratio, to either once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening or biennial faecal immunochemical testing. Details on the design and baseline results are described in a previous article [Citation24]. The present cross-sectional study included all 36,065 attenders in the sigmoidoscopy arm. We then excluded 355 (1%) participants with missing information on bowel cleansing. The sigmoidoscopies were performed at two screening centres in South-East Norway by sixteen consultants in gastroenterology and twenty-four gastroenterology trainees. The trainees completed three to six months of endoscopy training before they performed unsupervised screening sigmoidoscopies. We have previously shown the excellent colonoscopy quality achieved by the trainees, outperforming experienced consultants on several KPIs [Citation25]. KPIs were prospectively registered in an electronic, dedicated screening database. The endoscopists were asked to perform the web-based educational program for the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) [Citation26]. Supplementary to this, endoscopy images and videos with different bowel cleansing qualities were assessed at regular screening centre staff meetings to improve and maintain consensus and reduce inter-endoscopist variations in scoring practice.

On attendance at the screening centre, participants were asked to provide written informed consent and bowel symptoms were registered; overt rectal bleeding, recent changes in bowel habits, diarrhoea, constipation, bloating, abdominal pain, alternating bowel habits (both diarrhoea and constipation) and other symptoms.

Bowel preparation for sigmoidoscopy was performed using a 240-mL sorbitol enema administered on attendance at the screening centre. All sigmoidoscopies were performed with the Olympus Evis Exera III system, Olympus colonoscopes; CF H180DL, CF-HQ190L, PCF-PH190L, PCF-H190DL and a magnetic imaging system (Scope guide), Olympus Europa, Hamburg, Germany was available for most sigmoidoscopies, but its use was not recorded. CO2 was the standard insufflation gas. During the allocated 20-minute time slot, the endoscope was advanced as far as possible without causing undue pain, until limitations in bowel cleansing did not permit further advancement, the participant wanted to stop, or a neoplastic lesion ≥ 1 cm was detected. Otherwise, smaller lesions were usually removed at sigmoidoscopy.

The randomized screening trial was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics in Southeast Norway (2011/1272) and is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01538550). The trial was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the Helsinki declaration.

Key performance indicators

Bowel cleansing quality

Adenoma detection rate (ADR)

ADR was defined as the proportion of examinations with at least one adenoma detected during sigmoidoscopy (including lesions detected at sigmoidoscopy, but not removed for histopathological diagnosis until work-up of screen-positives at full colonoscopy). In order to ascertain that an adenoma removed at colonoscopy was the one detected at sigmoidoscopy, we used the following criteria [Citation21]: Difference in polyp size estimates should be less than 3 mm for polyps <10 mm and less than 5 mm for polyps ≥10mm. Difference in localization level estimates with a straight endoscope should be less than 5 cm up to level 30 cm from anus, and less than 10 cm for localization levels beyond 30 cm from the anus. Advanced adenomas included adenomas ≥ 10 mm or with villous components or high-grade dysplasia. Non-advanced adenomas were defined as adenomas <10 mm with low-grade dysplasia.

Complete examination rate

The sigmoidoscopy was considered complete if the descending-sigmoid junction was reached as judged by the endoscopist or having reached at least an insertion depth of 35 cm from the anus with straight endoscope.

Colonoscopy referral rate

Proportion of participants referred for a work-up colonoscopy. According to the trial protocol, participants were referred for colonoscopy if sigmoidoscopy showed a lesion larger than 10 mm, CRC, a lesion with high-grade dysplasia or villous component or three or more adenomas. If poor bowel cleansing precluded the removal of detected lesions, the participants were usually referred for colonoscopy rather than having a second sigmoidoscopy.

Duration of examination

Time from the start to the end of the examination in minutes including time spent on polyp removal.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-square test for trend was used to assess the association between bowel cleansing quality and categorical variables. The analysis of variance was used to assess the association between bowel cleansing quality and duration of sigmoidoscopy. Multivariable logistic regression models were applied to identify independent predictors of bowel cleansing quality, and to evaluate the independent effect of bowel cleansing quality on binary outcomes. All models included participants’ age and sex, presence of symptoms, screening centre and the endoscopist experience. For the endoscopist experience variable, we added a category for the missing values. The model for ADR in those referred to colonoscopy included also bowel cleansing quality at colonoscopy. The interaction between age (as a continuous variable) and sex was evaluated by adding the product term in the model. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. To assess the association between the individual endoscopists’ evaluation of bowel cleansing quality (dichotomized in excellent/good vs. partially poor/poor) and their individual ADR, we used a linear regression model with ADR as the dependent variable, and the rate of excellent/good bowel cleansing as the independent variable, weighted for the number of sigmoidoscopies performed.

All tests were two-sided with 5% significance level. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

This study included 35,710 individuals; 18,052 (50.6%) were women, and the mean age was 64 years (). Sex and age were equally distributed between the two screening centres. The average number of screening sigmoidoscopies performed by each endoscopist was 744 (interquartile range 131–1393); 3402 (9.5%) of the endoscopies were performed by consultants, 32,194 (90.2%) by trainees and allocation was missing in 114 (0.3%) sigmoidoscopies. In total 7265 participants (20.3%) reported at least one bowel symptom. The bowel cleansing quality was scored as excellent in 20,934 (58.6%) individuals, good in 6580 (18.4%), partly poor in 7097 (19.9%) and poor in 1099 (3.1%) (). At multivariable analysis, the probability of having an inadequate bowel cleansing (partly poor and poor cleansing) increased with age (OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.11–1.16 for each 5-year category) and was higher in men than in women (OR 1.34; 95% CI 1.28–1.41), while it did not depend on the presence of symptoms (OR 1.03; 95% CI 0.96–1.09). Consultants reported inadequate bowel cleansing more often than trainees (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.23–1.44). The effect of age was stronger in men than in women (p-value for interaction: <0.001): the odds of having an inadequate bowel cleansing increased by 17% every five years of age in men (OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.14–1.20), and by 9% every five years of age in women (OR 1.09; 95% CI 1.07–1.13).

Table 1. Characteristics of study population and endoscopy setting and association with quality of bowel cleansing at sigmoidoscopy.

shows the associations between bowel cleansing quality and KPIs for sigmoidoscopy screening. In 31,580 (88.4%) individuals a complete sigmoidoscopy was performed. Out of 4130 (11.6%) incomplete sigmoidoscopies, 1404 (3.9%) were interrupted because of undue patient-reported pain and 1952 (5.5%) sigmoidoscopies were incomplete because of inadequate bowel cleansing. In total, 2.2% of sigmoidoscopies were incomplete due to other reasons (technical difficulties, the patient’s wish to interrupt the examination or an unmotivated/unprepared patient, equipment failure, stricture, complications, or use of more time than the time slot allowed). More examinations performed by trainees than consultants were incomplete (12.1% vs. 6.5%; p < 0.001), but ADR did not differ (16.4% vs. 15.7%, p = 0.34). A complete sigmoidoscopy was carried out in 90.3%, 89.4%, 88.0% and 50.0% (p for trend <0.001) of examinations with excellent, good, partially poor and poor bowel cleansing quality, respectively. The corresponding sigmoidoscopy ADR was 17.0%, 16.6%, 14.5% and 13.0% (p for trend < 0.001). Among the 32,443 individuals who underwent sigmoidoscopy but no work-up colonoscopy, the corresponding figures were 12.4%, 11.4%, 8.6% and 3.8% (p for trend < 0.001). The bowel cleansing quality significantly affected the detection of non-advanced adenomas, but not the detection of advanced adenomas or cancers.

Table 2. Univariate analysis: endoscopy quality metrics and association with bowel cleansing at sigmoidoscopy.

Among the 3267 individuals referred for colonoscopy, the detection rate for advanced adenomas was 57.3%, 54.0%, 51.0% and 39.6% (p for trend < 0.001) in examinations with excellent, good, partially poor and poor bowel cleansing quality at sigmoidoscopy, respectively. The corresponding figures for non-advanced adenomas were 29.9%, 35.7%, 36.0% and 45.4% (p for trend < 0.001), and for all adenomas 87.1%, 89.7%, 86.9% and 85.0% (p for trend 0.67).

In multivariable analysis, compared to excellent bowel cleansing quality, partially poor and poor bowel cleansing quality were associated with higher colonoscopy referral rates, with ORs of 1.24 (95% CI 1.14–1.36) and 2.10 (95% CI 1.78–2.47), respectively (). Also, compared to excellent bowel cleansing quality, we found that good, partially poor and poor bowel cleansing quality were associated with lower detection rates for neoplastic lesions during sigmoidoscopy, with ORs of 0.89 (95% CI 0.83–0.96), 0.76 (95% CI 0.71–0.82) and 0.66 (95% CI 0.55–0.79). In Supplementary Table 1, we reported the multivariable analysis stratified by sex, age, and screening centre. Trends were consistent in all strata.

Table 3. Multivariable analysis: referral for colonoscopy and adenoma detection at sigmoidoscopy and follow-up colonoscopy.

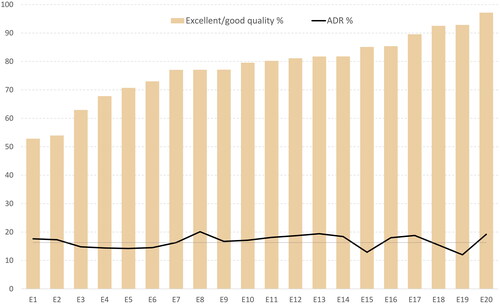

Among the 20 endoscopists who performed more than 500 sigmoidoscopies in the trial, the individual endoscopists’ evaluation of the bowel cleansing quality varied greatly, with rates of excellent/good bowel cleansing quality ranging from 53% to 97% (). However, we could not find an association between the individual endoscopists’ evaluation of bowel cleansing quality and their individual ADR. Endoscopists who rated bowel cleansing as good or excellent in a high proportion of their sigmoidoscopies often had an adenoma detection rate similar to those who less often rated bowel cleansing as good or excellent (0.18% increase in adenoma detection rate for each percentage unit increase in excellent/good bowel cleansing quality; 95% CI −0.91% to 1.26%; p = 0.735).

Figure 1. Quality of bowel cleansing and adenoma detection rate at sigmoidoscopy by individual endoscopists.

Footnote: Twenty endoscopists (E1 to E20) who performed at least 500 flexible sigmoidoscopies were selected. Individuals with adenocarcinomas detected at sigmoidoscopy were excluded from the calculation of ADR (mean ADR 16.3%, dotted horizontal line).

Discussion

In this study we assessed the impact of inadequate bowel cleansing quality on KPIs in sigmoidoscopy screening. We found a rate of 23.4% inadequate bowel cleansing in screening sigmoidoscopy causing a significant reduction in ADR, complete sigmoidoscopy rate and increased referral rate to work-up colonoscopy. Thus, inadequate bowel cleansing potentially reduces both the long-term efficacy of sigmoidoscopy screening and its cost-effectiveness. Male sex and increasing age were predictors for inadequate bowel cleansing consistent with findings regarding inadequate bowel cleansing quality for colonoscopy [Citation27]. One previous study has reported that low ADR at sigmoidoscopy increases the risk of interval cancer [Citation28].

Prior randomized controlled trials assessing bowel cleansing quality during sigmoidoscopy and using comparable enema preparations, showed rates of inadequate cleansing from 7% to 19% [Citation21,Citation29–34]. The variation may partly be explained by variations in volume, substance and timing of the enema and differences between the study populations. However, another plausible explanation for this discrepancy could be that due to the lack of a validated bowel preparation scale for sigmoidoscopy, different scoring systems were used to assess bowel cleansing quality.

In a previous Norwegian trial (NORCCAP), using the same enema preparation and an identical bowel cleansing score as in our trial, bowel cleansing was rated as inadequate in 14% of the sigmoidoscopies, compared to 23%, in our study. Though, the age groups included in the two trials differ from 50–64 years in the NORCCAP trial to 50–74 years in ours. Still, we observed a higher rate of inadequate bowel cleansing of 21.7% even for those younger than 65 years. An important difference is that the endoscopists in our trial were trained to use the validated BBPS during colonoscopy which may cause a more conservative assessment of the bowel cleansing quality and thus, contributing to the difference between the two Norwegian studies. This assumption is supported by a similar ADR in NORCCAP and our trial (any neoplasm in 14% (50–54 years), 19% (55–59 years), 20% (60–64 years) in NORCCAP vs. ADR 11% (55–54 years), 21% (55–59 years), 23% (60–64 years) in our trial.

The increased sigmoidoscopy ADR with improving bowel cleansing quality is in line with the trend in the baseline data from the NORCCAP trial and the UK flexible sigmoidoscopy trial (UKFSST) [Citation21,Citation22]. In NORCCAP, any neoplasm was detected in 18% of the participants with excellent bowel cleansing compared to 15% in the participants with adequate or poor bowel cleansing [Citation21]. In the UKFSST, the ADR in examinations with excellent bowel cleansing was 11.5%, versus 12.0% in examinations with good and 10,7% of examinations with adequate bowel preparation [Citation22]. In the UKFSST, individuals with poor bowel cleansing quality at the initial sigmoidoscopy were excluded from the analysis, since 70% of them (1653 of 2363) had a repeat sigmoidoscopy.

In our study, the referral rate for work-up colonoscopy was 8.3% for participants with excellent bowel preparation, while 18.0% of those with poor bowel preparation were referred for colonoscopy, resulting in an increased burden on participants and higher costs of the screening program. According to the protocol, only participants with advanced adenoma, CRC or at least three non-advanced adenomas at sigmoidoscopy should be referred for colonoscopy. However, our data show that referral to colonoscopy was not in accordance with the protocol. Possibly, if one adenoma was found in a sigmoidoscopy with inadequate bowel cleansing quality, endoscopists were concerned of overlooking further neoplasia or preferred referring to colonoscopy instead of removing a polyp under unfavourable and possibly risky circumstances. In this pragmatic trial, we do not consider this a protocol deviation, but as a pragmatic decision that would have been made also in routine clinics. Furthermore, whether to reschedule to a sigmoidoscopy or refer to colonoscopy in the presence of poor bowel preparation is both a question of cost-benefit and participant burden. The limited incremental cost for a colonoscopy of €60 compared to sigmoidoscopy [Citation35] in Norway may be in favour of scheduling colonoscopy. Nevertheless, it is essential to improve the bowel preparation regimens to improve the diagnostic outcome of sigmoidoscopy and give it justice as a viable screening option when compared to other screening methods.

We found significant differences in the assessment of bowel cleansing quality among endoscopists, but no association with the ADR. We therefore do not believe that the true bowel cleansing differs between the endoscopists but rather the perception and thereby the grading of bowel cleansing. This is contrary to the result of the UK study showing that endoscopists with high ADR judged the quality of bowel cleansing more strictly than those with low ADRs [Citation22]. The variation in sigmoidoscopy ADRs among endoscopists has been previously confirmed [Citation28,Citation36].

Our study demonstrates two important issues; 1. Inadequate bowel cleansing is associated with lower adenoma detection at sigmoidoscopy and higher referral to work-up colonoscopy causing decreased screening benefits for the participants and increasing burden for both participants and the screening programme and lowering cost-effectiveness. 2. Implementation of a validated, reliable, and easily applicable rating scale for bowel cleansing quality is crucial for the improvement of sigmoidoscopy screening. Such a scale may prevent potential confusion and difficulties in comparing the results of clinical trials and may clarify the quality performance of sigmoidoscopies in clinical practice as well as contribute to facilitate the development of improved bowel preparation for sigmoidoscopy.

The strength of this study is the population-based design of the main trial, the high number of examinations, and the high number of endoscopists and two participating centres making the result more valid and generalizable.

The major limitation of this study, as in previous sigmoidoscopy trials, is the lack of a valid and reliable bowel preparation rating scale for sigmoidoscopy. We have previously shown an excellent agreement between the four-point scale and the BBPS in colonoscopies [Citation24]. However, BBPS may not be appropriate in sigmoidoscopies, where endoscopists rarely perform washing to avoid the risk of blockage of the suction channel, and where washing causes more peristalsis and thereby impaired vision due to movement of proximal bowel contents into the distal colon. One previous trial has compared water-assisted intubation with CO2 intubation during screening sigmoidoscopy and reported significantly lower ADR in water-assisted examinations, possibly confirming our assumption [Citation37]. Poorer bowel cleansing was not reported but may be questioned in the absence of a validated rating scale. Another limitation is the challenge to determine the real ADR during sigmoidoscopy as commonly adenoma findings are not confirmed histologically before work-up colonoscopy and referral is based on the endoscopists´ subjective judgement. This might be more important in the presence of poor bowel preparation. Furthermore, possible differences in insertion depths make it difficult to assess the ADR in association with bowel cleansing.

Conclusion

Inadequate bowel cleansing reduces the efficacy of sigmoidoscopy screening by lower adenoma detection at sigmoidoscopy and increases the referral rate to work-up colonoscopy. Although the main finding was as expected, the study is of relevance due to the lack of conclusive data at this regard. Implementation of a validated and reliable rating scale for sigmoidoscopy and improved bowel preparation is crucial for further investigation within this field.

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design: KRR, GH, TdL.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: KRR, EB, ALS, MN, DHN, ØH, MB, GH, TdL.

Drafting of the manuscript: KRR, ALS, EB

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: KRR, EB, ALS, MN, DHN, ØH, MB, GH, TdL.

Statistical analysis: EB, KRR

All authors approved the final report and are accountable for all aspects of this work.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (57 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s). The bowel preparation was provided free of charge by Ferring Pharmaceuticals; none of the authors disclose relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Data availability statement

Access to research data for external investigators, or use outside of the current protocol, will require approval from the Norwegian Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethic and the Bowel cancer screening in Norway steering committee (information available on the project website https://www.kreftregisteret.no/screening/Tarmscreeningpiloten/). Research data are not openly available because of the principles and conditions set out in articles 6[1] (e) and 9 [2] (j) of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Questions regarding data access should be directed to the corresponding author, Anna Lisa Schult, [email protected].

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660.

- Bretthauer M, Løberg M, Wieszczy P, et al. Effect of colonoscopy screening on risks of colorectal cancer and related death. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(17):1547–1556. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2208375.

- Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, et al. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9726):1624–1633. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60551-x.

- Holme Ø, Løberg M, Kalager M, et al. Effect of flexible sigmoidoscopy screening on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(6):606–615. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8266.

- Juul FE, Cross AJ, Schoen RE, et al. 15-year benefits of sigmoidoscopy screening on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: a pooled analysis of randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(11):1525–1533. doi: 10.7326/m22-0835.

- Segnan N, Armaroli P, Bonelli L, et al. Once-only sigmoidoscopy in colorectal cancer screening: follow-up findings of the Italian randomized controlled trial–SCORE. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(17):1310–1322. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr284.

- Schoen RE, Pinsky PF, Weissfeld JL, et al. Colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality with screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(25):2345–2357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114635.

- Hassan C, East J, Radaelli F, et al. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) guideline - Update 2019. Endoscopy. 2019;51(8):775–794. doi: 10.1055/a-0959-0505.

- Rembacken B, Hassan C, Riemann JF, et al. Quality in screening colonoscopy: position statement of the European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE). Endoscopy. 2012;44(10):957–968. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325686.

- Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(1):31–53. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.07.058.

- Kaminski MF, Thomas-Gibson S, Bugajski M, et al. Performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) quality improvement initiative. Endoscopy. 2017;49(4):378–397. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-103411.

- Levin TR, Farraye FA, Schoen RE, et al. Quality in the technical performance of screening flexible sigmoidoscopy: recommendations of an international multi-society task group. Gut. 2005;54(6):807–813. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.052282.

- Clark BT, Rustagi T, Laine L. What level of bowel prep quality requires early repeat colonoscopy: systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of preparation quality on adenoma detection rate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(11):1714–1723; quiz 1724. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.232.

- Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, et al. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European panel of appropriateness of gastrointestinal endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(3):378–384. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02776-2.

- Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58(1):76–79. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.294.

- Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(19):1795–1803. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907667.

- Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, et al. The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(6):1207–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.051.

- Rai T, Navaneethan U, Gohel T, et al. Effect of quality of bowel preparation on quality indicators of adenoma detection rates and colonoscopy completion rates. Gastroenterol Rep . 2016;4(2):148–153. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gov002.

- Valori RM, Damery S, Gavin DR, et al. A new composite measure of colonoscopy: the performance indicator of colonic intubation (PICI). Endoscopy. 2018;50(1):40–51. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-115897.

- Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, et al. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(7):1696–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05827.x.

- Gondal G, Grotmol T, Hofstad B, et al. The Norwegian colorectal cancer prevention (NORCCAP) screening study: baseline findings and implementations for clinical work-up in age groups 50–64 years. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(6):635–642. doi: 10.1080/00365520310003002.

- Thomas-Gibson S, Rogers P, Cooper S, et al. Judgement of the quality of bowel preparation at screening flexible sigmoidoscopy is associated with variability in adenoma detection rates. Endoscopy. 2006;38(5):456–460. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925259.

- Bevan R, Blanks RG, Nickerson C, et al. Factors affecting adenoma detection rate in a national flexible sigmoidoscopy screening programme: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(3):239–247. doi: 10.1016/s2468-1253(18)30387-x.

- Randel KR, Schult AL, Botteri E, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with repeated fecal immunochemical test versus sigmoidoscopy: baseline results from a randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(4):1085–1096.e1085. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.11.037.

- Schult AL, Hoff G, Holme Ø, et al. Colonoscopy quality improvement after initial training: a cross-sectional study of intensive short-term training. Endosc Int Open. 2023;11(1):E117–e127. doi: 10.1055/a-1994-6084.

- Calderwood AH, Logan JR, Zurfluh M, et al. Validity of a web-based educational program to disseminate a standardized bowel preparation rating scale. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(10):856–861. doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000000028.

- Gandhi K, Tofani C, Sokach C, et al. Patient characteristics associated with quality of colonoscopy preparation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):357–369 e310. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.08.016.

- Rogal SS, Pinsky PF, Schoen RE. Relationship between detection of adenomas by flexible sigmoidoscopy and interval distal colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(1):73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.002.

- Atkin WS, Hart A, Edwards R, et al. Single blind, randomised trial of efficacy and acceptability of oral picolax versus self administered phosphate enema in bowel preparation for flexible sigmoidoscopy screening. BMJ. 2000;320(7248):1504–1508; discussion 1509. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7248.1504.

- Fincher RK, Osgard EM, Jackson JL, et al. A comparison of bowel preparations for flexible sigmoidoscopy: oral magnesium citrate combined with oral bisacodyl, one hypertonic phosphate enema, or two hypertonic phosphate enemas. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(8):2122–2127. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01308.x.

- Gidwani AL, Makar R, Garrett D, et al. A prospective randomized single-blind comparison of three methods of bowel preparation for outpatient flexible sigmoidoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(6):945–949. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9111-x.

- Osgard E, Jackson JL, Strong J. A randomized trial comparing three methods of bowel preparation for flexible sigmoidoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(7):1126–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00342.x.

- Underwood D, Makar RR, Gidwani AL, et al. A prospective randomized single blind trial of Fleet phosphate enema versus glycerin suppositories as preparation for flexible sigmoidoscopy. Ir J Med Sci. 2010;179(1):113–118. doi: 10.1007/s11845-009-0403-8.

- Weissfeld JL, Schoen RE, Pinsky PF, et al. Flexible sigmoidoscopy in the PLCO cancer screening trial: results from the baseline screening examination of a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(13):989–997. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji175.

- Aas E. Kostnader vedscreening av tykk- og endetarmskreft basert på tall fra piloten i Østfold og Bærum. https://www.kreftregisteret.no/globalassets/publikasjoner-og-rapporter/tarmkreftscreening/kostnadsanalyse_pilot_screening_tykk-endetarmskreft.pdf.

- Bretthauer M, Skovlund E, Grotmol T, et al. Inter-endoscopist variation in polyp and neoplasia pick-up rates in flexible sigmoidoscopy screening for colorectal cancer. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38(12):1268–1274. doi: 10.1080/00365520310006513.

- Rutter MD, Evans R, Hoare Z, et al. WASh multicentre randomised controlled trial: water-assisted sigmoidoscopy in English NHS bowel scope screening. Gut. 2021;70(5):845–852. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321918.