Abstract

Background and aims

Women with Lynch Syndrome (LS) have a high risk of colorectal and endometrial cancer. They are recommended regular colonoscopies, and some choose prophylactic hysterectomy. The aim of this study was to determine the impact of hysterectomy on subsequent colonoscopy in these women.

Materials and methods

A total of 219 LS women >30 years of age registered in the clinical registry at Section for Hereditary Cancer, Oslo University Hospital, were included. Data included hysterectomy status, other abdominal surgeries, and time of surgery. For colonoscopies, data were collected on cecal intubation rate, challenges, and level of pain. Observations in women with and without hysterectomy, and pre- and post-hysterectomy were compared.

Results

Cecal intubation rate was lower in women with hysterectomy than in those without (119/126 = 94.4% vs 88/88 = 100%, p = 0.025). Multivariate regression analysis showed an increased risk of challenging colonoscopies (OR,3.58; CI: 1.52–8.43; p = 0.003), and indicated a higher risk of painful colonoscopy (OR, 3.00; 95%CI: 0.99–17.44, p = 0.052), in women with hysterectomy compared with no hysterectomy. Comparing colonoscopy before and after hysterectomy, we also found higher rates of reported challenging colonoscopies post-hysterectomy (6/69 = 8.7% vs 23/69 = 33.3%, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Women with hysterectomy had a lower cecal intubation rate and a higher number of reported challenging colonoscopy than women with no hysterectomy. However, completion rate in the hysterectomy group was still as high as 94.4%. Thus, LS women who consider hysterectomy should not be advised against it.

Introduction

Lynch Syndrome (LS) is a hereditary cancer syndrome caused by pathogenic germline variants in the mismatch repair (MMR) genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2. Individuals with LS have up to 60% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). However, risk varies between the different genes, with MSH2 and MLH1 conferring the highest risk of CRC whilst PMS2 presents the lowest [Citation1]. Lifelong surveillance with colonoscopy every second year is recommended from the age of 25, and annually if adenomatous polyps are detected. Due to the high incidence of tumors in the right colon in LS patients, complete colonoscopies including the cecum are crucial. Previous studies have shown that regular colonoscopies reduce the risk and mortality of CRC in patients with LS [Citation2–4]. However, a recent study from the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database could not confirm this risk reduction of CRC [Citation5]. Nevertheless, it was claimed that early CRC detection still is important for survival.

In addition to their high risk of CRC, women with LS have up to 50% lifetime risk of endometrial cancer (EC) [Citation1]. Hence, endometrium surveillance is offered from age 30–35. Prophylactic removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) is an option for women with LS from the age of 40–45 [Citation6, Citation7]. Many also undergo surgery due to cancer.

Studies indicate that prior hysterectomy can make colonoscopy more difficult to perform and more painful for the patient [Citation8, Citation9]. One explanation is that major abdominal and pelvic surgeries may cause adhesions, and that removal of the uterus gives more space in the abdomen, which can cause loop formation of the colon. Painful colonoscopies might have an impact on the completeness of the endoscopy and the adherence of patients to surveillance programs. However, the participants in the previous studies [Citation8, Citation9] were women who had colonoscopy for various reasons, and to our knowledge, they did not include women with LS.

The aim of our study was therefore to determine the impact of hysterectomy on colonoscopy in women with LS.

Materials and methods

All patients who receive genetic counseling and testing for hereditary cancer at the Department of Medical Genetics (DMG) at Oslo University Hospital (OUH) are registered in the Quality Register for Hereditary Cancer (QRHC). An invitational letter with information about the study was sent to women included in the QRHC, aged 35–90, with a pathogenic variant in one of the MMR-genes. Those who consented to inclusion answered a questionnaire regarding their history of hysterectomy or any other earlier abdominal surgeries, place and date for the last colonoscopy, intestinal diseases, weight and height. For those who had undergone hysterectomy, information regarding indication for and year of the surgery was also recorded.

In Norway, dedicated units specialized on endoscopy in patients with Lynch Syndrome do not exist. The women in our study therefore had colonoscopies in their local hospitals. The National Quality Register for Endoscopies, Gastronet, receives endoscopy reports from several hospitals across Norway. In 2019, approximately 500 endoscopists from 50 different units reported to Gastronet. From Gastronet, for the period 2010–2019, information was collected from the women′s last performed colonoscopy about completion of the procedure and how painful it was. Patient perceived pain was categorized as follows: 1= no pain, 2= some pain, 3 = moderate pain, 4 = severe pain. Data on cecal intubation time, the level of experience of the endoscopist, and the type of scope and method used, were not available. For colonoscopies not registered in Gastronet, we collected information from medical records. For all women, we collected detailed information about the colonoscopy procedure from medical records: Use and dose of sedatives and analgesics before and during the colonoscopy, whether polyps or cancers were detected, complications (bleeding, perforation, other), whether cecum had been reached, reason for not reaching cecum (poor bowel preparation, stricture and other reasons) and challenges. A colonoscopy was defined as ‘challenging’ if one of the following was reported in the medical records: (1) difficulties due to probable adhesions (colon tissue stiffness), (2) difficulties due to loop-formation, (3) ‘difficult or challenging colonoscopy’ noted in the medical records but not further specified by the endoscopist. For the women with hysterectomy, we also collected information from colonoscopies performed before the surgery if available. For these women, data from two performed colonoscopies were included: the last colonoscopy before hysterectomy and the last colonoscopy after hysterectomy. In cases of several repeated colonoscopies after performed hysterectomy, the most recent colonoscopy was included. For those with hysterectomy or other prior abdominal surgery, we registered whether the surgery was performed laparoscopically or open. Prior abdominal surgery was categorized as other pelvic surgery, colon resection (colon cancer), rectal cancer, caesarean section and other abdominal surgery. We excluded those who had had a total or partial colectomy (colon resection), or missing medical records. Data were studied in the total cohort, including all participants (women with hysterectomy and women with no hysterectomy), and a sub-cohort, including the women with hysterectomy who had colonoscopies performed both before and after this procedure. We examined rate of completion (cecal intubation rate), challenges and painfulness of the colonoscopies performed.

Ethics

The women provided written informed consent before inclusion in the study. The study was approved as a quality-of-care study by the Data Protection Commissioner at OUH.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of the study participants were described as frequencies (percentages). Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used for the statistical comparison of the categorical variables in the two groups of participants (hysterectomy and no hysterectomy). A p value of less than 0.05 was regarded as significant. For paired data (data on colonoscopies performed before and after the hysterectomy in the same woman), McNemar’s test was used. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for challenging colonoscopy and painful colonoscopy were estimated using multivariate logistic regression analysis with prior hysterectomy, age, BMI, other prior abdominal/pelvic surgeries and use of sedatives/analgesics as independent variables. BMI was categorized as <25kg/m2 or >25kg/m2. Prior abdominal or pelvic surgery was categorized as ‘laparoscopic surgery’, ‘open abdominal surgery’ or ‘caesarean section’. Data on the women’s own pain perception was dichotomized to ‘no pain’ if they answered no pain or some pain, and to ‘painful colonoscopy’ if they answered moderate or severe pain. The statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 17.

Results

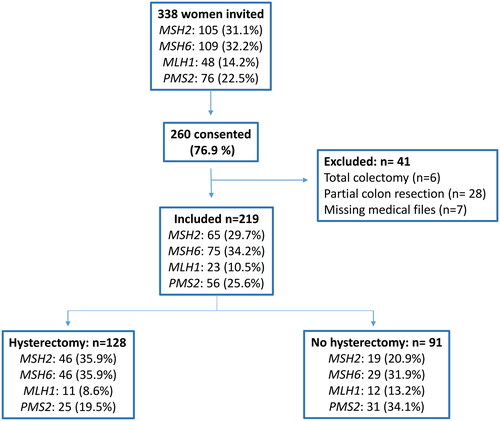

In total, 338 women were invited to participate in the study. After exclusion, 219 consenting patients were included, and of these 128 (128/219 = 58.4%) had a hysterectomy (). Reasons for hysterectomy, description of the participants and previous other abdominal surgery is shown in and .

Figure 1. Study flow chart illustrating included patients according to gene and hysterectomy/no hysterectomy.

Table 1. Description and reasons for hysterectomy in total cohort and according to gene.

Table 2. Prior abdominal and pelvic surgery, bowel disorders and BMI in hysterectomy and no hysterectomy groups.

Total cohort: colonoscopies in hysterectomy and no hysterectomy women

Observations from five colonoscopies were excluded from the analyses because the procedure had not been completed due to strictures/colon cancer. In the no hysterectomy group, a significantly higher proportion (88/88 = 100%) of the colonoscopies included the cecum compared with 119/126 (94.4%) in the hysterectomy group (p = 0.025). The risk ratio of 0.94 (0.91–0.99) confirms a significantly lower probability for reaching cecum in the hysterectomy group (). The proportion of reported challenging colonoscopies in the hysterectomy group was 44/126 (34.9%), compared with 10/88 (11.4%) in the no hysterectomy group (p < 0.001), giving a risk ratio of 3.1 (1.63–5.77) for challenging colonoscopies in the hysterectomy group. In sub-analyses comparing type of reported challenges in the two groups, the only significant difference was that colonoscopies performed in the hysterectomy group were more likely to be complicated by adhesions (colon tissue stiffness). There was no significant difference in the percentage of women who received analgesics or sedatives in the two groups (). Multivariate regression analysis confirmed that there was an increased risk of challenging colonoscopies in women with hysterectomy (OR, 3.58; CI: 1.52–8.43; p = 0.003) (). Neither BMI, age, prior abdominal surgery or the use of sedatives or analgesics were significant predictors for challenging colonoscopy (data not shown). When excluding the women with any other prior abdominal surgery, we still found an association between reported challenging colonoscopy and hysterectomy (p = 0.004) (), and multivariate regression analyzes also confirmed a significant increased risk of challenging colonoscopy after hysterectomy (OR: 2.99 CI:1.13–7.92; p = 0.027) in this subgroup ().

Table 3. Cecum intubation rate, challenges, use of analgesics/sedatives and pain perception during colonoscopy in hysterectomy and no hysterectomy groups (total cohort).

Table 4. Odds ratio for challenging and painful colonoscopy in women with hysterectomy as compared with women without hysterectomy.

Table 5. Results of colonoscopies in women with no other prior abdominal surgery.

There was no significant difference in self-reported experiences of pain in the hysterectomy group compared with the no hysterectomy group when all four categories (no pain, some pain, moderate pain, and severe pain) were assessed (p = 0.274). However, when dichotomizing the answers to ‘no pain’ (no or some pain) and ‘painful colonoscopy’ (moderate or severe pain), there was a tendency towards a higher proportion of patient reported pain in the hysterectomy group (). Multivariate regression analysis showed that there was a borderline significant higher risk of painful colonoscopy in women with hysterectomy (OR, 3.00; 95%CI: 0.99–17.44, p = 0.052) (). Among the women with hysterectomy, 82/126 (65.1%) received analgesics and/or sedatives before/during the colonoscopy, compared with 51/88 (58%) in the no hysterectomy group (p = 0.257) ().

Sixty-seven (52.3%) of the hysterectomies were performed laparoscopically. When comparing challenging colonoscopy and pain perception for laparoscopic versus open hysterectomy, there was no significant difference.

Sub-cohort: colonoscopies before and after hysterectomy

Sixty-nine (69/128 = 53.9%) of the women with hysterectomy had undergone a colonoscopy both prior to and after the hysterectomy. After hysterectomy, there was a significantly higher number of reported challenging colonoscopies, colonoscopies with loop formations, and a higher proportion of women who received analgesics or sedatives (). One (1.5%) of the colonoscopies performed prior to hysterectomy and three (4.3%) performed after hysterectomy, were not completed to cecum (p = 0.500). The one patient in which cecum was not reached prior to hysterectomy, also had an incomplete colonoscopy after hysterectomy.

Table 6. Results of colonoscopies before and after hysterectomy (the sub-cohort).

Discussion

There is limited knowledge on the impact of hysterectomy on later colonoscopies in women with LS. In this study, we found an increased number of reported challenging colonoscopies in women with prior hysterectomy. We also found a significant lower cecal intubation rate in women with hysterectomy. However, cecal intubation rates in the hysterectomy group of the main cohort were still as high as 94.4%. Skilled endoscopists should be able to intubate the cecum in >90% of all cases and in >95% of the cases when screening is indicated [Citation10]. Despite the increased rate of challenges, these criteria were almost met also in the women who had undergone hysterectomy in our study.

In our study, almost 40% of the women with hysterectomy had undergone the surgery due to cancer. Knowledge of how this surgery affects subsequent colonoscopies is therefore of importance not only for those who consider a hysterectomy to reduce their risk of EC, but also for those who have had cancer.

Several studies indicate that prior hysterectomy is a risk factor for incomplete colonoscopy, for prolonged cecal intubation time or for more difficult colonoscopy [Citation8, Citation11–15]. In a meta-analysis of nearly 6000 patients, Clancy et al. [Citation8] found that the colonoscopy completion rate was significantly reduced in patients with a history of hysterectomy compared with those with no history of pelvic surgery (87.1% vs 95.5%). None of these above-mentioned studies included women with known LS. In our study, we found similar differences, however we observed a higher cecal intubation rate in both hysterectomy and no hysterectomy women than in previous studies. One reason might be that the endoscopists are eager to reach the cecum knowing that LS tumours often have a proximal location. Garret et al. [Citation13] found that post hysterectomy adhesions to the sigmoid colon made colonoscopies more difficult and painful. In our study, there was also a significant association (p < 0.001) between colon stiffness/adhesions and hysterectomy. Adhesions might be one of the reasons for the observed higher proportion of reported challenging colonoscopies in women after hysterectomy in our study.

Results from other studies, indicate that different types of surgery may affect colonoscopies differently. Nam et al. [Citation15] reported that a prior gynecological surgery (hysterectomy, myomectomy of the uterus and ovarian or fallopian tube surgery) significantly prolonged cecal intubation time, but other abdominal surgeries did not. Aday et al. [Citation11] found that previous umbilical herniorrhaphy was associated with prolonged cecal intubation time, but that appendectomy and hepatobiliary surgery were not. In a recent meta-analysis [Citation16] they did not find that prior abdominal surgery prolonged cecal intubation time. However, in this study they did not analyze the association between cecal intubation time and the different types of abdominal surgery. Unfortunately, we did not have any data on cecal intubation time in our study. Nonetheless, we did find that the type of surgery affected colonoscopies differently; prior hysterectomy caused challenging colonoscopies, but other prior abdominal surgery did not. Removal of larger organs, like the uterus, may be more likely to cause post-operative adhesions and anatomical changes, which might facilitate loop-formation.

Several studies have examined risk factors for patients’ perception of pain during colonoscopy [Citation9, Citation12, Citation17–19], but the results are conflicting. Dyson et al. [Citation18] found that prior hysterectomy is associated with a significantly greater level of moderate/severe discomfort (18. 8% vs 10.4%), while Lacasse et al. [Citation17] did not. In our study we used data from Gastronet with a four-point scale of patient pain perception. The same method was used in a Norwegian study by Holme et al. showing that prior abdominal surgery is a risk factor for pain during colonoscopy [Citation9]. In Norway, it has not been a standard practice to administer sedation prior to endoscopy. After the study by Holme in 2013 (9) sedation has been more commonly offered. In other countries, sedation is used in all surveillance colonoscopies. In our study, many women did not receive sedatives and/or analgesics. We found that a higher number of women with hysterectomy reported painful colonoscopies compared with women without, but the difference was not statistically significant. In the multivariate regression analysis we did find a borderline significant higher risk of painful colonoscopy in women after hysterectomy (p = 0.052). In this analysis, we adjusted for whether the patients received analgesics and sedatives, but we were not able to adjust for dosage and type of analgesics/sedatives due to several different combinations of medications. We found no significant difference in the percentage of women who received analgesics or sedatives in the two groups. However, due to the smaller sample sizes in each group as defined by the type of challenge or use of analgesics or sedatives, these latter tests might be underpowered. Unfortunately, only 36% of our patients responded to the Gastronet pain perception questionnaire. The low response rate might have biased our results. In summary, we found a tendency towards more painful colonoscopies in women with hysterectomy, and based on these findings, we suggest that women who have gone through hysterectomy should be offered analgesics and sedatives prior to the colonoscopy. However, a larger study population is needed to explore this further.

The high response rate (76.9%) is a strength with our study. Inclusion from several centers across the country also ensures a high degree of external validity. Moreover, data was collected from a national register and cross-checked with the individual patient records. However, our study has some limitations. The participants were invited based on mutation status, and we did not have access to data on hysterectomy at the time of invitation. Therefore, we did not know whether the response rate was related to hysterectomy status. Nonetheless, the distribution of mutations in the four MMR genes was approximately the same in all invited carriers and the final study cohort. A good measure of challenging colonoscopy would have been cecal intubation time. This information was not registered in Gastronet nor medical records. Instead, we used the description of the colonoscopies from medical records. In some cases, the colonoscopies were just described as ‘challenging’ without any further explanations such as loop formation or colon stiffness. Another limitation is that we lack data on the level of experience of the endoscopists, and use of different scopes and methods. These factors could affect the performance of the colonoscopies. Among the women with hysterectomy, the time from hysterectomy to the latest colonoscopy varied, which may have had influence on technical challenges and pain during endoscopy. We also do not know how many colonoscopies the women have undergone. Furthermore, among the women who had had colonoscopies both before and after hysterectomy, the time between the two colonoscopies that were compared varied, which again might have influenced the technical challenges and pain during colonoscopy. By including results from several colonoscopies for each woman, we could possibly get more precise results. Further studies are needed.

Conclusions

In our study, we found a significant higher cecal intubation rate in women with LS who had not undergone hysterectomy compared with those who had a prior hysterectomy. However, cecal intubation rates in the hysterectomy group were still as high as 94.4%. We also found that having undergone hysterectomy was associated with a higher number of reported challenging colonoscopies. Nonetheless, the high cecal intubation rate indicates that women with LS who wish to undergo hysterectomy should not be advised against it.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients that consented to inclusion in this study, and Foundation Dam/Norwegian Women’s Public Health Association for funding.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Dominguez-Valentin M, Sampson JR, Seppälä TT, et al. Cancer risks by gene, age, and gender in 6350 carriers of pathogenic mismatch repair variants: findings from the prospective Lynch Syndrome database. Genet Med. 2020;22(1):15–25. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0596-9.

- de Jong AE, Hendriks YMC, Kleibeuker JH, et al. Decrease in mortality in Lynch Syndrome families because of surveillance. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):665–671. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.032.

- Järvinen HJ, Aarnio M, Mustonen H, et al. Controlled 15-year trial on screening for colorectal cancer in families with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(5):829–834. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70168-5.

- Guillén-Ponce C, Molina-Garrido MJ, Carrato A. Follow-up recommendations and risk-reduction initiatives for Lynch syndrome. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12(10):1359–1367. doi: 10.1586/era.12.114.

- Møller P, Seppälä T, Dowty JG, et al. Colorectal cancer incidences in Lynch syndrome: a comparison of results from the prospective lynch syndrome database and the international mismatch repair consortium. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2022;20(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13053-022-00241-1.

- Crosbie EJ, Ryan NAJ, Arends MJ, et al. The Manchester International Consensus Group recommendations for the management of gynecological cancers in Lynch syndrome. Genet Med. 2019;21(10):2390–2400. doi: 10.1038/s41436-019-0489-y.

- Seppälä TT, Dominguez-Valentin M, Crosbie EJ, et al. Uptake of hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in carriers of pathogenic mismatch repair variants: a prospective Lynch Syndrome database report. Eur J Cancer. 2021;148:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.02.022.

- Clancy C, Burke JP, Chang KH, et al. The effect of hysterectomy on colonoscopy completion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(11):1317–1323. doi: 10.1097/dcr.0000000000000223.

- Holme O, Bretthauer M, de Lange T, et al. Risk stratification to predict pain during unsedated colonoscopy: results of a multicenter cohort study. Endoscopy. 2013;45(9):691–696. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344239.

- Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(1):31–53. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.07.058.

- Aday U. Impact of prior different abdominal or pelvic surgery on cecal intubation time: a prospective observational study. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2020;83(4):541–548.

- Chung YW, Han DS, Yoo K-S, et al. Patient factors predictive of pain and difficulty during sedation-free colonoscopy: a prospective study in Korea. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39(9):872–876. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.04.019.

- Garrett KA, Church J. History of hysterectomy: a significant problem for colonoscopists that is not present in patients who have had sigmoid colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(7):1055–1060. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181d569cc.

- Wang H-M, Chan H-H, Wu M-J, et al. Not only hysterectomy but also cesarean section can predict incomplete flexible sigmoidoscopy among patients with prior abdominal or pelvic surgery. J Chin Med Assoc. 2014;77(3):122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2013.11.007.

- Nam JH, Lee JH, Kim JH, et al. Factors for cecal intubation time during colonoscopy in women: impact of surgical history. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(6):377–383. doi: 10.4103/sjg.SJG_9_19.

- Jaruvongvanich V, Sempokuya T, Laoveeravat P, et al. Risk factors associated with longer cecal intubation time: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33(4):359–365. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-3014-x.

- Lacasse M, Dufresne G, Jolicoeur E, et al. Effect of hysterectomy on colonoscopy completion rate. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24(6):365–368. doi: 10.1155/2010/319623.

- Dyson JK, Mason JM, Rutter MD. Prior hysterectomy and discomfort during colonoscopy: a retrospective cohort analysis. Endoscopy. 2014;46(6):493–498. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1365462.

- Takahashi Y, Tanaka H, Kinjo M, et al. Prospective evaluation of factors predicting difficulty and pain during sedation-free colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(6):1295–1300. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0940-1.