ABSTRACT

A credible body of research has evolved on resilience and children exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV). This information can be drawn on for resilience-informed approaches specifically aimed at working with children exposed to IPV. Child exposure to IPV has been an area of growing interest with rates in both child welfare and community samples remaining at concerning levels. It is commonly accepted that a number of these children experience harmful effects. However, extant studies also indicate some children show resilience after IPV exposure. Yet little has been written on how resilience can be fostered with exposed children who are negatively affected. The authors offer a working definition of it, discuss related concepts, and summarize the resilience research regarding IPV-exposed children. As well, two case examples are presented for ways to foster resilience with IPV-exposed children. Suggestions are made for a resilience-informed approach with this population, and it is demonstrated how social workers can use this to reinforce a strengths-based framework. Suggestions for future research and practice are also made.

Introduction

With consistently high rates of child exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) being reported, investigated, and substantiated (Fallon et al., Citation2015; Sinha, Citation2010) and heightened risks for harmful effects (Holt, Buckley, & Whelan, Citation2008; Kimball, Citation2016; Wolfe, Crooks, Lee, McIntyre-Smith, & Jaffe, Citation2003), it is timely to propose a resilience-informed lens for working with this vulnerable population. This article summarizes the growing research literature on resilience and IPV-exposed children, offers a working definition of resilience and discussion of related concepts to IPV-exposed children, and provides two case examples to explore ways of understanding and fostering resilience with children and youth exposed to IPV.

The prevalence of child abuse, including childhood exposure to IPV, has been well established through large-scale studies conducted in North America. For example, the Canadian Medical Association Survey (Afifi et al., Citation2014) found one in three adults reports experiencing child sexual abuse, physical abuse, and/or exposure to IPV. In the United States, the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study revealed that 28% of longitudinal study participants experienced physical abuse, 22% reported sexual abuse, and 13% reported seeing their mothers treated violently (Felitti et al., Citation1998). Additionally, the U.S. National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence shows that one in four children reported victimization, including high rates of exposure to IPV (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, Citation2009; Hamby, Finkelhor, Turner, & Ormrod, Citation2010).

Further, American estimates indicate 15.5 million children are exposed to domestic violence annually (McDonald, Jouriles, Ramisetty-Mikler, Caetano, & Green, Citation2006), and in Canada estimates show that children in half a million households are exposed to spousal violence (Hotton, Citation2003; Sinha, Citation2010). IPV exposure is the most frequently reported form of child abuse in Canada, reported at the same rate as neglect and representing 41% of substantiated investigations in 2008 (Lefebvre, Van Wert, Black, Fallon, & Trocmé, Citation2013).

It is now commonly accepted that exposure to IPV can lead to psychosocial difficulties and mental health issues for many children and youth (Holt et al., Citation2008; Wolfe et al., Citation2003). For example, compared with their nonexposed peers, exposed children and youth experience more depression, anxiety, social withdrawal, impairment in regulating emotions, aggression and conduct problems, insecure attachment, and trauma effects (Carpenter & Stacks, Citation2009; Graham-Bermann, Gruber, Howell, & Girz, Citation2009; Herman-Smith, Citation2013; Holt et al., Citation2008; Katz, Stettler, & Gurtovenko, Citation2016; Kimball, Citation2016; Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, Citation2003; Margolin & Vickerman, Citation2011; Moylan et al., Citation2010; Wolfe et al., Citation2003). As well, diminished school performance and compromised academic achievement have been noted in IPV-exposed children (Kimball, Citation2016). These consequences constitute serious psychosocial problems in a child’s functioning that can create vulnerabilities over the life course.

Because of these concerning effects, therapeutic programs have been developed to serve these children and their parents—most often, mothers, the adult victims in the clear majority of investigated cases in child welfare systems (Alaggia, Gadalla, Shlonsky, & Daciuk, Citation2015; Alaggia, Regehr, & Jenney, Citation2012). Children exposed to IPV are seen in community-based domestic violence programs, as well as shelters and generalist services offering child and family therapy, where social workers are at the forefront of providing services. Some are evidence-based manualized programs with rigorous evaluation (Howell, Miller, Barnes, & Graham-Bermann, Citation2015). However, many are not, leaving social work practitioners seeking guidance regarding helpful approaches for intervention in general and resilience promotion.

This article aims to address some of these challenges and assist practitioners in four ways. First, we offer a working definition of resilience to support clinical practice with this population, based on a thorough reading of the theoretical and conceptual material available. We also discuss the related concepts of protective factors, adaptation, and recovery.

Second, we provide a summary overview of research findings on resilience related to children’s exposure to IPV extrapolated from 19 studies. The summary does not constitute a systematic review but rather offers a qualitative synopsis of a developing knowledge base. We searched scholarly databases for peer-reviewed articles on resilience by applying keywords of resilience, exposure to intimate partner violence, exposure to domestic violence, protective factors, and coping to extract publications addressing resilience issues in IPV-exposed children. The results are summarized using a socioecological framework.

Third, using two case studies, we suggest how resilience concepts can be applied to practice with children exposed to IPV. Finally, we discuss the complementarity of resilience and trauma-informed approaches and the compatibility of adopting a resilience-informed approach within social work.

Defining resilience

Social work as a profession promotes a strengths-based approach, rather than taking a deficit orientation to client casework. Thus, resilience-fostering work is highly compatible with social work practice as it provides a tangible means of operationalizing ways of practicing within a strengths-based framework. A resilience-informed lens emphasizes promoting healthy adaptation and recovery by recognizing and building on strengths to overcome adversity.

First and foremost, it is important to define resilience to appropriately ground our practice for all levels of intervention. Based on a combination of conceptual ideas offered by prominent resilience theorists (Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick, & Yeshuda, Citation2014; Ungar, Citation2013), we have developed and propose the following working definition because it reflects the essential elements of resilience: it involves a process of recovery, occurring over time, in response to an adverse event and/or ongoing adversity, best understood within a socioecological framework (Anderson & Bang, Citation2012; Ungar, Citation2013). The current authors developed this definition of resilience to help guide practice:

Resilience is a process of navigating through adversity, using internal and external resources (personal qualities, relationships, and environmental and contextual factors) to support healthy adaptation, recovery and successful outcomes over the life course (see www.makeresiliencematter.ca).

Protective factors and resilience

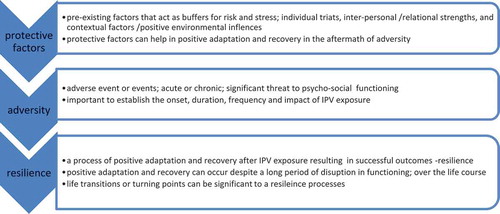

Any discussion of resilience necessitates acknowledging the significance of protective factors as contributors to the resilience process. However, protective factors are not the same as resilience, and even though the two terms have been used interchangeably, this leads to confusion (Benavides, Citation2014). We provide an explanation of these differences to frame this article—especially when considering the case studies.

To clarify, protective factors are those characteristics that are present with the individual and the environment before the onset of adversity and that can contribute to positive adaptation and recovery post adversity (Benavides, Citation2014; see Benavides, Citation2014, for a review of the literature on protective factors with IPV-exposed children). Resilience, on the other hand, is the process of navigating through adversity, where protective factors—indirect, direct, internal, and external—decrease the probability of negative psychosocial outcomes, contributing to overcoming adversity successfully, resulting in resilient responses (Benavides, Citation2014; Gewirtz & Edleson, Citation2007; Suzuki, Geffner, & Bucky, Citation2008). Resilience processes are now generally viewed as context based, expanding the field’s understanding beyond a focus on individual factors. Please see for important distinctions.

Summary of resilience research and IPV exposure

Due to an increased awareness of exposure to IPV as a form of child abuse and the numbers of children exposed, a body of research has been steadily evolving examining resilience within the context of exposure to childhood IPV specifically. Despite the well-documented negative effects (Holt et al., Citation2008), a good number of studies indicate that not all children are negatively affected and that some IPV-exposed children and youth retain healthy functioning or develop positive adaptation and are able to follow normal trajectories of human development (Edleson, Citation1999; Graham-Bermann et al., Citation2009; Herman-Smith, Citation2013; Holt et al., Citation2008; Kimball, Citation2016; Laing, Humphreys, & Cavanagh, Citation2013; Margolin, Citation2005; Stith et al., Citation2000). For example, in a recent extensive review of the literature, Laing and colleagues (Laing et al., Citation2013) found that 26% to 50% of IPV-exposed children were functioning as well as those who were not exposed. Such findings are instrumental in informing practice because we can use them to help identify specific factors associated with resilience. By identifying resilience with IPV-exposed children who are functioning well, practitioners can better help vulnerable children.

To guide the search strategy and review methods, Kiteley and Stogdon’s (Citation2014) literature review framework was used to (a) locate studies in peer-refereed journals to ensure a high quality of rigor; (b) extract and summarize significant findings; and (c) identify the most convincing findings that should be considered for future practice and program planning. Four electronic databases were searched: PsycINFO, Educational Resources Information Center (ERIC), Sociological Abstracts and Social Service Abstracts, and Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (ASSIA). Keywords used were: intimate partner violence, domestic violence, domestic abuse, partner abuse, children exposed to domestic violence, exposure to violence, family conflict, family violence, resilience, coping, emotional stability, emotional adjustment, psychological endurance, child maltreatment, child adjustment, risk, positive adaptation, positive development, turning points, and child development. The “cited by” function in Google Scholar was also used to expand search parameters and ensure that all relevant literature was captured.

The inclusion criteria were: English language quantitative and qualitative studies in peer-refereed scholarly journals for the past decade, 2006–2017, relating to childhood exposure to IPV and resilience. If child exposure to IPV was included in the sample those studies were examined. Conversely, articles investigating general child maltreatment where IPV exposure was not specifically identified were excluded. After exclusion criteria were applied, 19 studies were located for analysis and subjected to a thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). We then organized the extant research results into a socioecological framework—a recommended framework given that resilience is a process, multiply determined by an individual’s social ecology (Anderson & Bang, Citation2012; Ungar, Citation2013). In addition, the person-in-environment framework has long been held as compatible with social work practice with each level of the human ecology being addressed: individual child factors (intrapersonal), relational factors (interpersonal), and contextual and cultural factors (environmental) (Bogo, Citation2006).

summarizes the resilience factors identified in studies finding factors in more than one area of the socioecological framework—in other words, overlapping areas of the ecological categories. For example, Gonzales and colleagues (Gonzales, Chronister, Linville, & Knoble, Citation2012), in their in-depth study, identified intrapersonal, interpersonal, and contextual factors contributing to resilience. Other such examples are seen though this literature, especially when mixed methods were used.

Table 1. Socioecological Resilience Factors for Children Exposed to IPV.

Intrapersonal factors

Studies show positive correlations between specific intrapersonal characteristics and resilience. Individual characteristics cited include self-confidence, greater self-worth, emotion regulation, connection to spirituality, commitment to breaking the cycle of violence, motivation/goal orientation, academic success, internal locus of control, and an easy temperament (Gonzales et al., Citation2012; Howell & Miller-Graff, Citation2014; Martinez-Torteya, Anne Bogat, Von Eye, & Levendosky, Citation2009; Suzuki et al., Citation2008).

Other commonly cited individual characteristics include empathy/compassion, social competence, autonomy, sense of purpose, belief in gender equality, and positivity/positive outlook/optimism (Franklin, Menaker, & Kercher, Citation2012; Graham-Bermann et al., Citation2009; Jenney, Alaggia, & Niepage, Citation2016). Characteristics identified less frequently but of note include: trust in one’s instincts, resourcefulness, positive acceptance of change, humor, agreeableness, and emotional intelligence (Franklin, Menaker, & Kercher, Citation2012; Gonzales et al., Citation2012; Howell & Miller-Graff, Citation2014). Whether these qualities are the result of postadversity adaptation or an extension of protective preexisting factors is less clear. Even so, these findings are noteworthy as sources for fostering resilience.

Interpersonal factors

Having a safe relationship with one adult, one close secure relationship, usually maternal, and being protected by the parent who was victimized by IPV emerge as contributing factors leading to increased resilience (Anderson & Bang, Citation2012; Gonzales et al., Citation2012; Jenney et al., Citation2016; Ungar, Ghazinour, & Richter, Citation2013). Maternal sensitivity and parental warmth have been associated with higher levels of resilience, especially in warding off externalizing and internalizing problems (Graham-Bermann et al., Citation2009; Manning, Davies, & Cicchetti, Citation2014). Further, maternal mental health, positive parenting skills, maternal attunement, and lower levels of maternal trauma have been related to increased resilience in IPV-exposed children (Bogat, DeJonghe, Levendosky, Davidson, & von Eye, Citation2006; Graham-Bermann et al., Citation2009; Laing et al., Citation2013; Martinez-Torteya et al., Citation2009).

Not surprisingly, secure attachment with caregivers has also been associated with resilience in IPV-exposed children. A number of findings place healthy parent–child relationships at the center of positive adaptive functioning (Carpenter & Stacks, Citation2009; Graham-Bermann et al., Citation2009; Herman-Smith, Citation2013), with securely attached children having greater emotion regulation, positive peer and adult relationships, and better school performance. Secure attachment acts as a protective factor; thus, it is important to focus on strengthening attachment relationships and supporting attachment repair to promote resilience.

Further, Miller (Citation2014) found that large in-home social networks were associated with less internalizing and externalizing behaviors, suggesting that the presence of extended family members and other caregivers in the home positively affected children’s adjustment in the aftermath of IPV exposure. Other interpersonal factors of note were peer and social support outside of the family, as these factors have been found to increase resilience in IPV-exposed children (Howell & Miller-Graff, Citation2014; Kassis, Artz, Scambor, Scambor, & Moldenhauer, Citation2013; Owen et al., Citation2008; Tajima, Herrenkohl, Moylan, & Derr, Citation2011).

Contextual and cultural factors (environmental)

Studies focusing on contextual factors as potential sources of resilience is a growing area of interest (Anderson & Danis, Citation2006; Ungar et al., Citation2013). We have defined contextual factors as those influences attributed to the individual’s environment, such as neighborhood, community, culture, and sociopolitical conditions that directly influence resource availability and supports. In one of the few studies conducted on contextual factors originating from the environmental factors, Anderson and Bang (Citation2012) found that mothers’ education and secure, full-time employment were connected to higher resilience in their daughters who had been exposed to IPV and trauma. This is one clear example of how contextual factors contribute to growth opportunities: affordable education, secure employment, and access to affordable daycare for mothers—resource availability that is dependent on enriched environments and sociopolitical conditions—increase the likelihood of higher resilience in their IPV-exposed children.

Another study identified having a safe haven to retreat to and engaging in extracurricular activities as contributing to resilience (Gonzales et al., Citation2012). Access to extracurricular activities is also indicative of an environment (neighborhood, community), one that makes resources available to youth for escaping to, and engaging in, school- and/or community-based activities.

Similarly, investigators studying resilient women exposed to IPV as children found that contextualizing the violence, and developing strategies to exit to safe places to block out the abuser, contributed to their resilience processes as children (O’Brien, Cohen, Pooley, & Taylor, Citation2013). Again, these findings highlight the need for adequate resources and supports outside the home, such as community centers, libraries, and programming for youth offered within their environments, that provide vital avenues for escape, support, and development.

The context of the violence itself can influence resilience processes. Investigators in one study found that children’s resilience scores were related to the frequency of IPV-exposure events. For example, higher levels of perceived threat resulted in lower levels of child adjustment (Fortin, Doucet, & Damant, Citation2011). In other words, as IPV intensifies, perceived threat elevates, and children are more adversely affected. If early intervention is not available due to a lack of resources (i.e., long wait lists), or because hostile environmental conditions dissuade victimized parents from disclosing or seeking help (Alaggia et al., Citation2012), the context of the abuse must be considered in later interventions. The longer exposure to violence goes on before intervention occurs, the higher is the likelihood that child adjustment has been more affected. Contextual factors have a direct bearing on how long children are exposed to IPV. From a social ecological standpoint, these distal (indirect) factors are often connected to proximal (direct) factors.

Resilience concepts and their role in a strengths-based approach

Protective factors and resilience

Accordingly, identifying protective factors is an important aspect of working with IPV-exposed children and youth within a resilience-informed approach. For example, the literature on protective factors shows the following intrapersonal and interpersonal factors as positively correlated with children’s later resilience in response to their parents’ conflict: ego resilience, optimism, curiosity, hardiness, extraversion, self-efficacy, the ability to detach from problems, emotional self-regulation and positive self-concept, close bond with a caregiver in the first year of life, sociability with a strong sense of independence, intelligence, good health, self-motivation, and engagement in acts of required helpfulness (Benavides, Citation2014; Ungar et al., Citation2013).

Further, in terms of cultural factors, Sirikantraporn (Citation2013) discovered that biculturalism functioned as a protective factor in IPV exposure that contributed to resilience processes. By comparing two groups of IPV-exposed youth from South Asian backgrounds with youth from bicultural backgrounds, study findings showed that youth from bicultural backgrounds scored higher on resilience measures than the youth from unicultural backgrounds. However, the processes involved in this increased resilience have yet to be clearly identified. Overall, it is important for social work practitioners to identify, early on, which protective factors existed prior to IPV exposure so that they can then be elicited in facilitating resilience.

Adaptation and recovery as part of the resilience process

Elaborating on the resilience definition offered here, it is important to recognize that resilience can involve early positive adaptation and/or later recovery (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2013; Gonzales et al., Citation2012). Positive adaptation is a process when an individual adapts in healthy ways to adversity and achieves successful outcomes. Resilience is the outcome of positive adaptation. This usually involves drawing on internal resources while negotiating external resources to navigate through the adversity. Some individuals may even experience postadversity growth (i.e., adopting better coping strategies, learning new problem-solving skills, etc.). In treatment, clients offer surprising accounts of how extremely troubling adversities have made them a stronger person, as well as more compassionate, more independent, and more perceptive. Despite many people believing that adversities are necessarily damaging, we are learning that adverse experiences can have a duality about them, resulting in positive growth.

On the other hand, recovery occurs over a period of time and along various points of the life course. The process of recovery can be activated despite the development of maladaptive behaviors and/or prolonged unhealthy functioning (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2013). Theorists and researchers studying resilience as a dynamic process have cited life transitions, such as attaining higher education, getting married, or having children, as important turning points over the life course. These are points in people’s lives when individuals can either rise above challenging circumstances or, conversely, descend on a downward spiral (Rutter, Citation2012; Ungar et al., Citation2013; Zolkoski & Bullock, Citation2012). Recognizing important turning points and their potential for fostering resilience fits well within a strengths-based approach, offering hope and opportunities for growth over the life course.

Applying resilience concepts to practice: Two case illustrations

What can we learn from this knowledge, and how can we apply it to social work practice through a resilience-informed lens? Considering what we now know, we encourage practitioners to keep two primary tasks in mind when working with children exposed to IPV: (a) identify and promote existing protective factors to foster the resilience process and (b) seek opportunities to foster resilience processes through positive adaptation.

The following case illustrations exemplify ways in which this can be done. In keeping with ethical practices, these cases have been developed as composite illustrations to protect the identities of individual clients.

Optimizing protective factors

The following is an example of how practitioners can use a strengths-based approach to help uncover protective factors to foster the resilience process.

Simone is a 12-year-old whose mother is concerned about her social and emotional withdrawal since leaving Simone’s father after his abusive behavior escalated during the past 2 years. Drawing on a strengths-based assessment completed with Simone and her mother, the social worker discovered that Simone used to enjoy soccer and excelled at it. The importance of this discovery is confirmed by research that indicates extracurricular activities promoting talents and skills, such as sports, can foster a process of resilience with children and youth (Benavides, Citation2014; Gonzales et al., Citation2012; Suzuki et al., Citation2008). However, in the chaos of the separation and ensuing family disruption, Simone had stopped playing. While trying to reactivate Simone’s interest in this positive activity, the social worker found Simone was reluctant to take up soccer again. Through gentle questioning with Simone and her mother, the social worker learned that Simone’s father was a coach in her soccer league. Simone was limiting her contact with him to formally scheduled visits, so the prospect of returning to play soccer had become complicated and emotionally triggering for her.

Trauma effects are not uncommon in IPV-exposed children and triggers are to be expected. If trauma is present, a trauma-informed approach is necessary as described by Howell and colleagues (Howell et al., Citation2015) in their work with young children. When trauma is suspected or confirmed with clients it is advisable to respond to effects by: (a) giving clients choice and control, (b) building in safety wherever possible, (c) engendering trust, (d) working collaboratively, and (e) promoting client empowerment (Harris & Fallot, Citation2001). A trauma and resilience-informed perspective can work hand in hand.

The social worker supported Simone, with the help of her mother, in identifying another enjoyable activity creating safety and supporting the clients’ choice in moving forward. Simone loved swimming, so the social worker then assisted in finding affordable lessons at a public facility. Over time, Simone and her mother became “regulars” at the local pool and Simone later won a place on her school swimming team. Part of resilience-informed work includes important practical case management, as noted in this case study, an often minimized but nonetheless highly valuable function of social work.

As Simone’s story illustrates, finding a past strength and reactivating it is not always a straightforward process. Simone attached a negative meaning—perhaps a trauma reaction to having contact with her father—to what was once an esteem-building activity. Further, access to community resources was a challenge: because Simone’s neighborhood did not have a community center, she had to travel to find a pool. The social worker helped them locate a facility and, had it been necessary, was prepared to find a subsidy for Simone’s lessons. Resilience-informed approaches require working through a socioecological lens with every intervention. Therefore, being aware of the client’s environment assets and limitations should remain a priority for the practitioner to ensure successful followthrough.

Fostering resilience through adaptation

The following case description is an example of working with a young boy toward positive adaptation, resulting in a resilience fostering process. Paolo is a serious 9-year-old who looks young for his age. His teachers observed that he was on the periphery of his peer group interactions. Since his parents’ separation, due to his stepfather’s abusive behavior toward his mother, he had become even more awkward in his social interactions. Of note, Paolo’s mother exhibited a positive outlook on life, and although beleaguered by the challenges of single parenting and being harassed by her ex-partner, she had a wonderful sense of humor. Facilitators for the mothers’ group she attended also noted how much her demeanor contrasted with her son’s serious nature.

One of the group facilitators for the children’s group Paolo attended took it upon himself to teach Paolo to tell jokes and deliver them in funny ways. Over time, Paolo became quite proficient at telling jokes and loved the positive attention it garnered. The facilitator also encouraged Paolo’s mother to teach him jokes at home and read humor,s with him. Not only did Paolo develop a skill in telling jokes, but the shared joking and reading activities also acted as an attachment-reparation activity. It should be noted that an evaluation of attachment was not conducted, so that the shift to a more secure attachment between mother and son was based on observational data. Future programming should consider administering attachment measures to be able to collect more reliable data.

During the marriage, Paolo’s stepfather had been so demanding of his mother’s attention that she was left with little emotional energy for nurturing her relationship with Paolo. This was a significant issue to be addressed in their relationship. Research shows that a relationship with a safe adult, especially a parent, combined with secure attachment, fosters resilience in the face or aftermath of adversity (Anderson & Bang, Citation2006; Carpenter & Stacks, Citation2009; Graham-Bermann et al., Citation2009; Herman-Smith, Citation2013; Manning et al., Citation2014; Martinez-Torteya et al., Citation2009).

In this scenario, the practitioners made important observations about mother and son. One of the children’s workers then used creativity and spontaneity to help Paolo develop a skill, the teaching of which was then transferred to his mother to continue at home. Without a doubt, there were specific factors at play in favor of a positive outcome. The mother’s warmth and sensitivity toward her son were evident. These maternal characteristics are identified in the research literature as resilience-promoting factors (Manning et al., Citation2014). Good maternal mental health is essential, yet the negative effects of IPV can undermine mental health (Howell & Miller-Graff, Citation2014). Clearly, this situation would have been further complicated had maternal capacity been compromised. If this had been the case, individual treatment for the parent may have been necessary to address mental health problems and to shore up her capacity to respond to her child’s needs.

Limitations

This article focuses on a specific aspect of the life course dealing with children and preadolescents through the case studies provided. It does not cover adolescents or transitional age youth, which would be valuable to include in future practice considerations.

Adversity in this article is presented in a fixed and static way—the exposure described in these vignettes has a beginning, middle, and end. However, many children are born into adverse conditions, and some children are exposed to IPV in utero, thus experiencing chronicity of exposure running over the course of their infancy, childhood, and adolescence. The case examples used for this article present clinical cases from programs and services where the exposure has largely ceased for the clients, because the IPV survivors have left the abusive relationship. In addition, children who have been exposed to IPV may have other adversities with which they are dealing. It is difficult to completely tease out the effects of IPV exposure from other forms of child abuse that may co-occur. As with all good social work practice, assessments are critical to conduct to be clear about the multiplicity of issues and the source of problem behaviors and symptoms.

Implications for practice with IPV-exposed children through a resilience-informed lens

A rapidly developing knowledge base on resilience factors and processes can serve as a catalyst for re-thinking practice with vulnerable children. To date, little has been written on how to utilize resilience concepts, or a resilience-informed lens in practice with this population. Only one case study is available on promoting resilience in a child exposed to IPV. In that study, Howell and colleagues (Howell et al., Citation2015) provide a case analysis of a 6-year-old who received a group intervention, the Preschool Kids Club (PKG), an evidence-based, manualized program for IPV-exposed preschoolers (Graham-Bermann, Citation2000; Howell et al., Citation2015).

Howell and colleagues (Howell et al., Citation2015) recommend that, together with a developmentally informed and trauma-focused orientation, it is equally important to assess strengths to assist in resilience promotion to guide comprehensive treatment planning. Despite these important findings, the practice reality is such that not all practitioners have access to or the means to provide manualized interventions such as PKG. Working effectively within a strengths-based perspective requires practitioners to have tools to assess protective factors, strengths, and sources of resilience (Grych, Hamby, & Banyard, Citation2015; Howell et al., Citation2015). However, resilience measures that focus on evaluating protective and resilience factors to target positive adaptation interventions are difficult to find.

The Resilience Portfolio Model is one newly conceptualized model, developed as an approach to assess protective factors and processes to promote resilience when vulnerabilities have become apparent in IPV-exposed children (see Grych et al., Citation2015). Other potential measures used by the authors of this article include the Strengths and Difficulties Scale (Goodman, Citation1997), the Child Emotion Management Scale (Zeman, Shipman, & Suveg, Citation2002), and the Connors Davidson-RISC (CD-RISC) measure of resilience for children 10 years and older (Connor & Davidson, Citation2003). These measures can be completed by children with the assistance of trained facilitators. The one drawback with the CD-RISC is that children under the age of 10 cannot participate, and with the other measures, very young children under 6 years of age would be unable to give direct information about their strengths and emotion regulation.

Further, interventions need to be tailored to each client based on a thorough assessment of resilience-fostering opportunities. In recalling Paolo, the practitioner set out a deliberate intervention to promote a sense of humor, which then increased Paolo’s sense of self-efficacy and social skills. The practitioner then suggested attachment-reparation activities to bolster the mother–child relationship. As well as fostering intrapersonal skills for her son and addressing attachment ruptures in the mother–son relationship, the group program offered Paolo’s mother opportunities for shoring up interpersonal support and located additional resources to provide material support.

In collaboration with children and their families, identifying and locating avenues for esteem-promoting activities are important undertakings. Simone’s case exemplifies this—the practitioner addressed the challenge of reactivating Simone’s motivation through a positive activity and then helped to find an affordable facility for Simone to take swimming lessons. The practitioner was also prepared to access financial subsidies if necessary. Social workers have specialized knowledge on how to work with systems to benefit their clients, underscoring the value of case management. As Simone’s and Paolo’s situations demonstrate, the process of identifying and fostering resilience came about through community-based services and supports.

In addition, the two cases offer examples of creative resilience-fostering activities (joke-telling and swimming), which, when understood within the context of the research on children’s exposure and resilience, suggest that as practitioners, we need to be open to unique and uncommon sources for fostering resilience. At the same time, identifying resilience fostering activities must include determining the nature, duration, and frequency of IPV exposure to understand in what ways and how deeply the client’s worldview has been affected, especially when IPV exposure has been determined to be traumatic. Acute, short-term exposure to IPV effects can differ from chronic, long-term exposure effects (Herman-Smith, Citation2013). It is important to establish an understanding of the context because the details of the abuse environment can have specific impacts on each individual (O’Brien et al., Citation2013).

Developing this understanding involves the parent and child discussing some of the details of the violence and the coping strategies they may have adopted, including those that were maladaptive or were initially adaptive but have become problematic over time. Understanding that problematic behaviors may have started as coping strategies is important in helping to eliminate and replace them with positive adaptations. This is often the case when trauma symptoms become apparent, necessitating the use of a trauma-informed approach as mentioned earlier, and reinforcing the importance of using dual, complementary lenses, such as trauma- and resilience-informed approaches.

Conclusion

Practitioners can now take advantage of a growing knowledge base concerning resilience and children’s exposure to IPV when working with vulnerable children identified and referred for therapeutic services. This article has demonstrated how to apply resilience concepts to clinical practice to help social work practitioners use research in practical ways to becoming resilience informed. In addition, the authors have articulated how using a resilience-informed lens for assessment and intervention supports practice from a strengths-based framework and a socioecological approach. However, there is more work to be done in developing the use of a resilience-informed lens to foster resilience with children exposed to IPV. One area of note is in the lack of clinical assessment tools. While some tools and models have been offered in this article, overall, current assessment approaches are in stages of early development of focusing on identifying protective factors and sources of resilience to facilitate resilience-fostering interventions.

Building on the available research literature, we have provided a working definition of resilience, discussed associated concepts, and, through two case illustrations, provided material from which to conceptualize and operationalize resilience processes to consider for application in practice with children and youth exposed to IPV. Finally, working within a socioecological framework will help social workers retain this resilience-informed lens in planning support strategies and treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate the critical input and feedback from practitioners working in this area in the initial phases of this project.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for their generous support of this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ramona Alaggia

Ramona Alaggia, PhD, MSW, is associate professor in social work and the Factor-Inwentash Chair in Children’s Mental Health, University of Toronto. Her teaching and research focus on gender-based violence, sexual abuse disclosures, domestic violence exposure, and resilience processes.

Melissa Donohue

Melissa Donohue, MSW, is a social worker in the child and adult mental health field working in community- and hospital-based settings. As a research associate with the University of Toronto, her clinical research is focused on supporting healthy human development and resilience-promoting processes.

References

- Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H. L., Boyle, M., Taillieu, T., Cheung, K., & Sareen, J. (2014). Child abuse and mental disorders in Canada. Canadian Medical Association, April 22, 2014, cmaj.131792. doi:10.1503/cmaj.131792

- Alaggia, R., Gadalla, T., Shlonsky, A., Jenney, A., & Daciuk, J. (2015). Does differential response make a difference: Examining domestic violence cases in child protection services. Child and Family Social Work, 20(1), 83–95.

- Alaggia, R., Regehr, C., & Jenney, A. (2012). Risky business: An ecological analysis of intimate partner violence disclosure. Research on Social Work Practice, 22(3), 301–12.

- Anderson, K., & Danis, F. (2006). Adult daughters of battered women. Affilia, 21(4), 419–432. doi:10.1177/0886109906292130

- Anderson, K. M., & Bang, E. (2012). Assessing PTSD and resilience for females who during childhood were exposed to domestic violence. Child & Family Social Work, 17(1), 55–65. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2011.00772.x

- Benavides, L. E. (2014). Protective factors in children and adolescents exposed to intimate partner violence: An empirical research review. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32(2), 93–107. doi:10.1007/s10560-014-0339-3

- Bogat, G. A., DeJonghe, E., Levendosky, A. A., Davidson, W. S., & Von Eye, A. (2006). Trauma symptoms among infants exposed to partner violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30, 109–125. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.09.002

- Bogo, M. (2006). Social work practice: Concepts, processes, & interviewing. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77–101.

- Carpenter, G. L., & Stacks, A. M. (2009). Developmental effects of exposure to domestic violence in early childhood: A review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(8), 831–839. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.03.005

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. T. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18, 76–82. doi:10.1002/da.10113

- Edleson, J. L. (1999). Children’s witnessing of adult domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 14(8), 839–870. doi:10.1177/088626099014008004

- Fallon, B., Van Wert, M., Trocmé, N., MacLaurin, B., Sinha, V., Lefebvre, R., … Goel, S. (2015). Ontario incidence study of reported child abuse and neglect – 2013, Major findings. Retrieved from http://cwrp.ca/sites/default/files/publications/en/ois-2013_final.pdf

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2009). Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 403–411.

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2013). Psychological resilience: A review and critique of definitions, concepts, and theory. European Psychologist, 18(1), 12–23. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000124

- Fortin, A., Doucet, M., & Damant, D. (2011). Children’s appraisals as mediators of the relationship between domestic violence and child adjustment. Violence and Victims, 26(3), 377–392. doi:10.1891/0886-6708.26.3.377

- Franklin, C. A., Menaker, T. A., & Kercher, G. A. (2012). Risk and resiliency factors that mediate the effect of family-of-origin violence on adult intimate partner victimization and perpetration. Victims & Offenders, 7(2), 121–142. doi:10.1080/15564886.2012.657288

- Gewirtz, A. H., & Edleson, J. L. (2007). Young children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: Towards a developmental risk and resilience framework for research and intervention. Journal of Family Violence, 22, 151–163. doi:10.1007/s10896-007-9065-3

- Gonzales, G., Chronister, K. M., Linville, D., & Knoble, N. B. (2012). Experiencing parental violence: A qualitative examination of adult men’s resilience. Psychology of Violence, 2(1), 90–103. doi:10.1037/a0026372

- Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. doi:10.1111/jcpp.1997.38.issue-5

- Graham-Bermann, S. A. (2000). Preschool Kids’ Club: A preventive intervention program for young children exposed to violence. Ann Arbor, MI: Department of Psychology, University of Michigan.

- Graham-Bermann, S. A., Gruber, G., Howell, K. H., & Girz, L. (2009). Factors discriminating among profiles of resilience and psychopathology in children exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV). Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(9), 648–660. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.01.002

- Grych, J., Hamby, S., & Banyard, V. (2015). The resilience portfolio model: understanding healthy adaptatin in victims of violence. Psychology of Violence, 5(4), 343–354. doi:10.1037/a0039671

- Hamby, S., Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., & Ormrod, R. (2010). The overlap of witnessing partner violence with child maltreatment and other victimizations in a nationally representative survey of youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(10), 734–741. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.03.001

- Harris, M., & Fallot, R. D. (2001). Using trauma theory to design service systems. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Herman-Smith, R. (2013). Intimate partner violence exposure in early childhood: An ecobiodevelopmental perspective. Health & Social Work, 38(4), 231–239.

- Holt, S., Buckley, H., & Whelan, S. (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 797–810. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004

- Hotton, T. (2003). Childhood aggression and exposure to violence in the home. Crime and Justice Research Paper Series, Statistics Canada. Catalogue No. 85-561-MWE2003002.

- Howell, K. H., Miller, L. E., Barnes, S. E., & Graham-Bermann, S. A. (2015). Promoting resilience in children exposed to intimate partner violence through developmentally informed intervention: A case study. Clinical Case Studies, 14(1), 31–46. doi:10.1177/1534650114535841

- Howell, K. H., & Miller-Graff, L. E. (2014). Protective factors associated with resilient functioning in young adulthood after childhood exposure to violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(12), 1985–1994. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.010

- Jenney, A., Alaggia, R. & Niepage, M. (2016). “The lie is that it’s not going to get better”: Narratives of resilience from childhood exposure to intimate partner violence. International Journal of Child and Adolescent Resilience, 4(1), 64–76.

- Kassis, W., Artz, S., Scambor, C., Scambor, E., & Moldenhauer, S. (2013). Finding the way out: A non-dichotomous understanding of violence and depression resilience of adolescents who are exposed to family violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(2–3), 181–199. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.11.001

- Katz, L. F., Stettler, N., & Gurtovenko, K. (2016). Traumatic stress symptoms in children exposed to intimate partner violence: The role of parent emotion socialization and children’s emotion regulation abilities. Social Development, 25(1), 47–65. doi:10.1111/sode.2016.25.issue-1

- Kimball, E. (2016). Edleson revisited: Reviewing children’s witnessing of domestic violence 15 years later. Journal of Family Violence, 31, 625–637. doi:10.1007/s10896-015-9786-7

- Kiteley, R., & Stogdon, C. (2014). What is a literature review? In K. Wharton & E. Milman (eds.), Literature reviews in social work (pp. 5–22). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Kitzmann, K. M., Gaylord, N. K., Holt, A. R., & Kenny, E. D. (2003). Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 339–352. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.339

- Laing, L., Humphreys, C., & Cavanagh, K. (2013). Social work & domestic violence: Developing critical & reflective practice. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Lefebvre, R., Van Wert, M., Black, T., Fallon, B., & Trocmé, N. (2013). A profile of exposure to intimate partner violence investigations in the Canadian child welfare system: An examination using the 2008 Canadian Incidence Study of reported child abuse & neglect (CIS-2008). International Journal of Child and Adolescent Resilience, 1(1), 142–181.

- Manning, L. G., Davies, P. T., & Cicchetti, D. (2014). Interparental violence and childhood adjustment: How and why maternal sensitivity is a protective factor. Child Development, 85(6), 2263–2278.

- Margolin, G. (2005). Children’s exposure to violence: Exploring developmental pathways to diverse outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(1), 72–81.

- Margolin, G., & Vickerman, K. A. (2011). Post-traumatic stress in children and adolescents exposed to family violence: I. Overview and issues. Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice, 1(S), 63–73. doi:10.1037/2160-4096.1.S.63

- Martinez-Torteya, C., Anne Bogat, G., Von Eye, A., & Levendosky, A. A. (2009). Resilience among children exposed to domestic violence: The role of risk and protective factors. Child Development, 80(2), 562–577. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01279.x

- McDonald, R., Jouriles, E. N., Ramisetty-Mikler, S., Caetano, R., & Green, C. E. (2006). Estimating the number of American children living in partner-violent families. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 137–142. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.137

- Miller, L. E. (2014). In-home social networks and positive adjustment in children witnessing intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Issues, 35(4), 462–480. doi:10.1177/0192513X13478597

- Moylan, C. A., Herrenkohl, T. I., Sousa, C., Tajima, E. A., Herrenkohl, R. C., & Russo, M. J. (2010). The effects of child abuse and exposure to domestic violence on adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 53–63. doi:10.1007/s10896-009-9269-9

- O’Brien, K. L., Cohen, L., Pooley, J. A., & Taylor, M. F. (2013). Lifting the domestic violence cloak of silence: Resilient Australian women’s reflected memories of their childhood experiences of witnessing domestic violence. Journal of Family Violence, 28(1), 95–108. doi:10.1007/s10896-012-9484-7

- Owen, A. E., Thompson, M. P., Mitchell, M. D., Kennebrew, S. Y., Paranjape, A., Reddick, T. L., & Kaslow, N. J. (2008). Perceived social support as a mediator of the link between intimate partner conflict and child adjustment. Journal of Family Violence, 23(4), 221–230.

- Rutter, M. (2012). Resilience as a dynamic concept. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 335–344. doi:10.1017/S0954579412000028

- Sinha, M. (2010). Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile. Statistics Canada (Catalogue No. 85-224-X) Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada.

- Sirikantraporn, S. (2013). Biculturalism as a protective factor: An exploratory study on resilience and the bicultural level of acculturation among Southeast Asian American youth who have witnessed domestic violence. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4(2), 109–115. doi:10.1037/a0030433

- Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338

- Stith, S. M., Rosen, K. H., Middleton, K. A., Busch, A. L., Lundeberg, K., & Carlton, R. P. (2000). The intergenerational transmission of spouse abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family and Marriage, 62(3), 640–654. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00640.x

- Suzuki, S. L., Geffner, R., & Bucky, S. F. (2008). The experiences of adults exposed to intimate partner violence as children: An exploratory qualitative study of resilience and protective factors. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 8(1–2), 103–121. doi:10.1080/10926790801984523

- Tajima, E. A., Herrenkohl, T. I., Moylan, C. A., & Derr, A. S. (2011). Moderating the effects of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: The roles of parenting characteristics and adolescent peer support. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(2), 376–394. doi:10.1111/jora.2011.21.issue-2

- Ungar, M. (2013). Resilience, trauma, context, and culture. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14(3), 255–266. doi:10.1177/1524838013487805

- Ungar, M., Ghazinour, M., & Richter, J. (2013). Annual research review: What is resilience within the social ecology of human development? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 348–366. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12025

- Wolfe, D. A., Crooks, C., Lee, V., McIntyre-Smith, A., & Jaffe, P. (2003). The effects of children’s exposure to domestic violence: A meta-analysis and critique. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6(3), 171–187. doi:10.1023/A:1024910416164

- Zeman, J., Shipman, K., & Suveg, C. (2002). Anger and sadness regulation: Predictions to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 393–398.

- Zolkoski, S. M., & Bullock, L. M. (2012). Resilience in children and youth: A review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(12), 2295–2303. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.009