Abstract

The aim of this article is to present a pedagogical approach for history education. This approach is called Meaningful History and it outlines the process by which upper-level secondary history students can cultivate historical consciousness. Based on the notion of learning as meaning making and historical consciousness as a disposition to engage with history so as to make meaning of past human experience for oneself, the author describes a possible learning trajectory. Additionally, to show how this trajectory could apply to the classroom, the author offers three guidelines for educators to design and support such learning. These guidelines are: (1) negotiate the presence of the past, (2) inquire into the past with the help of habits of mind, (3) and build a sense of historical being. The guidelines are illuminated by examples that have been extracted from a design-inspired classroom experiment. In conclusion, the author suggests that future history education research investigate Meaningful History’s relevance and practicality in various settings.

Introduction

In an effort to challenge the traditional notion of history education as the transfer of information, history education research over the past decades has privileged a constructivist approach to history teaching and learning (Carretero et al., Citation2017; Chapman & Wilschut, Citation2015; Köster et al., 2014; Metzer & Harris, Citation2018; Stearns et al., Citation2000). It has generally endorsed the view that school history ought to be taught as a way of thinking about, and inquiring into humans’ existence in time. As part of this renewed conversation about what to teach and how to teach it, the field has elaborated the concept of historical consciousness, which is typically understood as a way to orientate in time by linking the past, present and future (Clark & Grever, Citation2018; Clark & Peck, Citation2019; Karlsson, Citation2011; Körber, Citation2015a; Lee, Citation2004; Rüsen, Citation2004, Citation2012; Seixas, Citation2012, Citation2017; van Straaten et al., Citation2016; von Borries, Citation2011; Zanazanian & Nordgren, Citation2019).

Two decades ago, one of the leading researchers in the field stated that the “formation of historical consciousness—not transmission of information about the ‘past’ itself—is the point and purpose of history teaching” (von Borries, Citation2011, p. 284). However, it is still unclear how the concept should apply to the classroom. As an influential history educationalist argues, the field is still faced with the “challenge in moving from the theoretical to an educational program” (Seixas, Citation2017, p. 61). Why is this move so challenging? While there is very little contention about the importance of historical consciousness for history education, there is little consensus when it comes to its definition.

The term in fact appears to be rather broad and elusive. Indeed, questions arise on multiple fronts when it comes to conceptualizing historical consciousness, as can be testified by the recent publication of a special issue (Zanazanian & Nordgren, Citation2019) and an exchange between two scholars in the field on the topic of translating concepts in and out of academic and national contexts (Körber, Citation2015b; Seixas, Citation2015b). For example, whether it is a specific intellectual and cultural achievement of Western modernity or a universal human capacity is still up for debate. It is also unclear how historical consciousness can refer to both a sense of collectiveness and of biographical self. Another crucial issue is that both the terms “history” and “consciousness” are intricate and contested terms that can be approached from different epistemological and ontological perspectives. Finally, an additional ambiguity can be found in the way scholars use historical consciousness in history education not only to study the phenomenon itself, but also as an analytical lens or a theoretical framework to study other topics related to narrative psychology, historiography, collective memory, and citizenship education.

Thus, it is not surprising that historical consciousness is often viewed as “hard to pin down” (Laville, Citation2004, p. 67), as “vague and rather enigmatic” (Grever & Adriaansen, Citation2019, p. 815) and as “a catch-all term which can be used quite differently” (Körber, Citation2015a, p. 6). That being said, the general lack of clarity about its definition does not necessarily need to be resolved by denying the concept’s polysemic and multifaceted nature in order to instead establish a widely accepted, definitive definition. As Nordgren (Citation2019) advises, scholars can instead strive for greater clarity and coherence in this debate by explaining and justifying their normative position, or in other words, by being transparent about the claims they make when they define historical consciousness, namely the values behind those claims and the reasons for making them. In what follows, I attempt to do just that.

The aim of this paper is to present an approach for teaching and learning history with the aim of cultivating students’ historical consciousness. The approach is called Meaningful History, because it offers a definition of historical consciousness that is based on the notion of learning as meaning making. The emphasis on meaning making is suggested as an alternative to competence development. Indeed, in recent years, efforts to operationalize historical consciousness for pedagogy have tended to link historical consciousness to competence in historical thinking or narrative competence (e.g., being able to construct and problematize historical questions, to evaluate and make historical judgments, to assess and interpret historical sources, to understand and apply substantive and second-order concepts) (Duquette, Citation2015; Eliasson et al., Citation2015; Körber & Meyer-Hamme, Citation2015; Seixas, Citation2015a; Waldis et al., Citation2015). In so doing, these efforts have contributed to the view that historical consciousness is not only an abstract “state of mind” but also a pedagogical “set of capabilities” (Körber, Citation2015a, p. 19) with clearly articulated domain-specific developmental processes and explicit, measurable learning achievements. Some of those efforts can be viewed as “competence models” (Körber, Citation2011). The notion of a competence model is grounded in a cognitive developmental perspective; learning refers to higher-order mental processing operations for effectively responding to a situation and thus demonstrating the mastery of knowledge, skills and attitudes for critical thinking, disciplined inquiry, and multiperspectival understanding.

Promoting such learning is undeniably important, but there is perhaps a tension in how the competency-based approach operationalizes historical consciousness. This can be likened to two divergent conceptions of mind and learning, as Bruner (Citation1996) proposed, i.e., the culturalist and the computationalist. On one hand, competence models are founded on the notion that historical consciousness is an existential and hermeneutic form of human meaning making that encompasses a vast, rich and ambiguous array of ways in which people and societies situate themselves in time and represent their past to themselves and others (i.e., culturalism). Yet on the other hand, by their very nature of being competence-driven, they operationalize its pedagogical goals and practices in terms of a precise, narrow set of knowledge, skills and attitudes required to carry out cognitive procedures to conduct and examine interpretations (i.e., computationalism).

In an attempt to deal with this tension, this paper presents a definition and pedagogy of historical consciousness that adopts more of a culturalist conception of mind and learning, based on the notions of learning as meaning making (Jarvis, Citation2018) and historical consciousness as the disposition to engage with history so as to make meaning of past human experience for oneself (Boix-Mansilla & Gardner, Citation2007; Nordgren & Johansson, Citation2015). I describe these notions in the first part of the paper, and building on those notions I also present a learning trajectory designed for upper-level secondary students. Cultivating students’ historical consciousness along this trajectory aims to facilitate meaning-making processes and practices, so students can engage with the material in ways that reflect their own experiences, as well as the interests, questions and concerns about the past that they bring to the classroom.

In the second part of the paper, I elaborate on three pedagogical strategies that aim to guide and support teachers in enacting the learning trajectory. The description of these guidelines is complemented by examples from a classroom study that sought to apply those particular guidelines to an actual classroom setting, which was done in collaboration with a high school teacher in the United States of America. This article does not intend to present the results of that study. The purpose, rather, is to propose a pedagogical approach that encourages the making of meaning toward cultivating historical consciousness. To conclude this article, I suggest areas of research to further investigate the applications of Meaningful History.

An envisioned learning trajectory

Learning as meaning making

The approach to learning taken in this paper draws on an idea that has been elaborated by several theories, such as cultural-historical psychology, pragmatism, constructivism, and social constructionism, namely that learning, as meaning making, is an active process that people engage in to “interpret situations, events, objects, or discourses, in the light of their previous knowledge and experience” (Zittoun & Brinkmann, Citation2012, p. 1806). Particularly, I draw on Peter D. Jarvis’ sketch of a comprehensive theory of human learning. His account attempts to cover educational, psychological, philosophical, neuropsychological and spiritual perspectives, following the assumption that, as Jarvis (Citation2018) wrote, “since learning is human, then every academic discipline that focuses upon the human being has an implicit theory of learning, or at least a contribution to make to our understanding of learning” (p. 18). For Meaningful History, learning refers to:

the combination of processes throughout a lifetime whereby the whole person—body (genetic, physical, and biological) and mind (knowledge, skills, attitudes, values, emotions, beliefs and senses)—experiences social situations, the perceived content of which is then transformed cognitively, emotively, or practically (or through any combination) and integrated into the individual’s biography resulting in a continually changing (or more experienced) person. (Jarvis Citation2018, p. 19)

Essentially, at the heart of learning is a transformation of experience that changes a person. Such an activity is a fundamental phenomenon of everyday life, because it helps us as humans constructively make sense of our experiences in our conscious interaction with the world. For this reason, it also helps us expand our conscious interaction with the world, because the more meaning we make and integrate, the more experience we develop, and thus learn to be and become a whole person, or “learn to be me,” in reference to the surrounding world (Jarvis, Citation2018, p. 24). In this sense, according to Jarvis (Citation2018), there are both “experiential” (i.e., transforming experience) and “existential” (i.e., transforming the person who learns) dimensions to learning.

While such transformations are subjective, they are nevertheless intertwined with intersubjective systems of meaning in Jarvis’ comprehensive understanding of learning. Indeed, his integrated vision accommodates the belief that learning is simultaneously an individual activity (i.e., the learner integrates new information to personal mental structures that include prior learning, tacit knowledge, past experiences, cultural background, personal views, and so on; c.f. Bransford et al., Citation1999; Novak, Citation1998) and a sociocultural activity (i.e., the learner participates in communities and thus mediates their particular discourses, practices and contexts; c.f. Robins, Citation2001; Wells, Citation1999; Wenger, Citation1998; Wertsch, Citation1998). In other words, the internal and interactional features of learning are interrelated rather than differentiable. Furthermore, Jarvis’ account acknowledges that learning is fundamentally a lifelong project (c.f. Bentley, Citation2012; Illeris, Citation2014; Jarvis, Citation2009), which concerns the nature of the person who is learning, and thus underlies an individual’s self-concept, self-development, and self-biography. It also acknowledges that learning is influenced by the learner’s position in and response to the political, ideological, economic, and social contexts in which learning takes place (c.f. Daniels et al., Citation2012; Giroux et al., Citation1988; Lave & Wenger, Citation1991).

Though I have merely outlined a few elements of his view, Jarvis’ account of learning and his embrace of theoretical and methodological diversity serve in a broad manner to define the notion of learning as: an educational endeavor designed to enable a learner to build and negotiate meaning from experience, and such meaning helps them be and become their own person in reference to the surrounding world.

Historical consciousness

The origins of the concept of historical consciousness can be traced back to modern Western thought and historical inquiry, namely, Enlightenment philosophies of history, historicism, hermeneutics, and phenomenology. These traditions distinctly conceptualize history as a form of thought or experience and establish it as a feature of the Western modern mode of existence, distinctively conscious of its temporality, of its being in history. The influence of these ideas is apparent in the works of prominent thinkers and social scientists of the twentieth century, such as Hans-Georg Gadamer, Raymond Aron, Hannah Arendt, John Lukacs, Hayden White, and Reinhart Koselleck, as well as scholars who since the 1970s have been theorizing the concept for the field of research on history education. While this body of literature is rich, my approach toward historical consciousness here does not endorse a particular theorist or school of thought. This is not to say that I ignore the influence of theory on how history education scholars understand the construct.

Rather, because I am interested in how it can be of use in educational practice, the way I articulate historical consciousness ultimately strives to help educators make decisions about design, lesson planning, instruction and assessment. My approach thus is inspired by Boix-Mansilla and Gardner’s (Citation2007) and Nordgren and Johansson’s (Citation2015) conceptualization of historical consciousness, because their work on, respectively, global consciousness and intercultural learning, has focused on the intricacies of teaching and learning.

Boix Mansilla and Gardner define global consciousness as “the capacity and the inclination to place our self and the people, objects, and situations with which we come into contact within the broader matrix of our contemporary world” (p. 57). In their classroom-based study that sought to apply the concept to instruction in different subjects, these authors consider that global consciousness positions the self along an axis of space, just as historical consciousness does along an “axis of time” (p. 59). To cultivate historical consciousness, in their view, is to cultivate three cognitive-affective capacities, which draw on Rüsen’s (Citation2004) theory of historical consciousness and on Damasio’s (Citation1999) neuropsychological understanding of human consciousness as a complex mental capacity that enables the construction of an autobiographical self. Those capacities are: sensitivity “toward objects [and circumstances] in our environment […] with which the self comes into contact”; understanding, or the “organization […] of mental representations” that enable us to “reinterpret experience” thus “conferring new meaning on our experiences;” and self-representation, or “the reflective capacity to understand ourselves as knowers and feelers—and as historical actors” (p. 58).

Nordgren and Johansson (Citation2015) also draw on Rüsen’s (Citation2005) notion of historical consciousness in their conceptual framework of intercultural learning. This framework is meant to be used “to analyse and heuristically raise questions about intercultural dimension in history education, or to guide the practical planning of history lessons” (p. 3). As such, they argue that the basic abilities of historical consciousness are: the ability to experience which is “expressed as sensitivity to the presence of the past around us;” the ability to interpret, which amounts to “mak[ing] sense of the past in the form of history” and thus “understanding the significance (or meaning) of an event, the causes behind a process of change, and the structure of historical narratives;” and the ability to orient, which means utilizing experience and interpretation “for the purpose of making sense of contemporary situations and for identifications” (pp. 4–5).

The overlap between these two views of historical consciousness can be explained by their reliance on ideas developed by Jörn Rüsen, one of the leading theorists in the field of history education. Grounded in the German history didactics tradition (c.f. Körber, Citation2011), his views on orientation in historical culture, his typology of the ontogenetic development of historical consciousness in relation to moral consciousness and narrative competence, his disciplinary matrix of historiography and the everyday life world, and his conception of historical narrative and narration have been especially influential. That being said, I do not seek to elaborate my definition of historical consciousness in relation to Rüsen’s theoretical considerations and the debates that have emerged in response to his work.

What I retain from Rüsen (Citation2004, Citation2005) essentially, via Boix-Mansilla and Gardner (Citation2007) and Nordgren and Johansson (Citation2015), is that historical consciousness refers to “a disposition to engage with history so as to make meaning of past human experience for oneself, or in other words, to make the historical past one’s own” (Popa, Citation2022, p. 4]) and that it is manifested in three interrelated and interdependent meaning-making processes—experiencing historical temporality, interpreting historical material, and orienting in practical life—and such processes can respectively develop three abilities—sensitivity toward the past, understanding of the past, representation of oneself in relation to history.

Underlying the definition of historical consciousness in Meaningful History is the assumption that history represents a lens through which humans can view and understand material and immaterial remnants of the past that have been preserved and given meaning through interactions between people over time; as such, it is also a lens through which we can make meaning in the present moment by building connections with a world beyond our own singular experience (Becker, Citation1932; Lee, Citation2011a; Osborne, Citation2006). In this sense, students come to their lessons already possessing this lens, which makes them think, feel and act in their own particular way. Furthermore, Meaningful History also assumes that consciousness, based on Boix-Mansilla and Gardner’s (Citation2007) reference to Damasio’s work, is the construction of the subjective mind in mutual interaction with the world, which involves a complex, integrated interplay of embodied mental processes, such as memories, knowledge, reflection, motivations, feelings, emotions, and expectations, that relate our experiences of the world to our changing autobiographical self.

Making meaning to cultivate historical consciousness

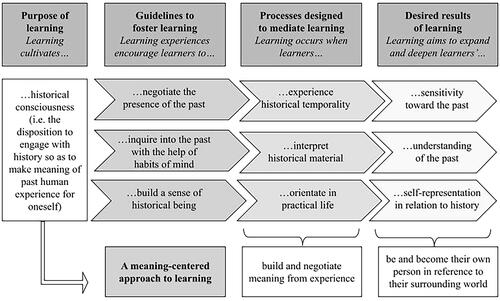

Meaningful History brings the notions of historical consciousness and learning as meaning making together and uses this intersection to envision the following learning trajectory (): to make the historical past their own, students need to build and negotiate meaning from experience, and they do this by experiencing historical temporality, interpreting historical material, and orienting in practical life; such learning can enhance their ability to be sensitive toward the past, to understand the past, and to represent themselves in relation to history, which helps students be and become their own person in reference to their surrounding world.

Guidelines to cultivate historical consciousness

This proposition about learning, however, leaves unanswered the questions of how educators can guide and support such learning and of how practical and feasible it might be to do so. Thus, in addition to defining historical consciousness and envisioning a learning trajectory, Meaningful History also proposes three guidelines for history teachers to facilitate learning (): negotiate the presence of the past, inquire into the past with the help of disciplinary and everyday habits of mind, and build a sense of historical being. These guidelines are grounded in the results of an extensive review and synthesis of literature on historical meaning making in education (Popa, Citation2022).

Moreover, I illustrate these guidelines with examples from a classroom experiment I conducted in 2018, in collaboration with a high school history teacher, Michael, who at the time taught in a public high school located in the suburban circle surrounding Boston (Popa, Citation2021). In this mixed-methods design-inspired study, I sought to answer the following questions: how did students engage in a learning sequence based on Meaningful History; and what were the challenges and affordances of the educational design, as perceived by the students and the teacher? The participants consisted of Michael and 21 of the 24 students enrolled in his Grade 11 Advanced College Preparatory (ACP) U.S. History course. Michael and I developed a unit on the topic of World War II history. We used a variety of pedagogical resources and materials, some of which were provided in the textbook, others from his previous teaching of the unit, and the rest from several resources freely available on the Internet. The purpose of this classroom experiment was to implement Meaningful History and to produce a thick description of student learning and of the educational design. In what follows, I explain the three guidelines that framed the planning and facilitation of learning throughout the unit.

Guideline 1. Negotiate the presence of the past

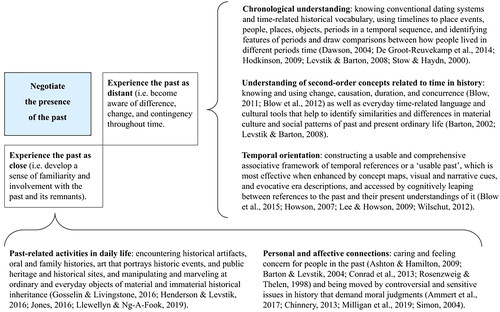

Though the past undeniably lies everywhere around us, its reality is beyond our direct experience, it is by its very nature gone and done, and no longer part of the present. In the ability to see and recognize the fragmentary traces and accounts of the past that are have been left as remnants of past reality, there is a tension, as Wineburg (Citation2001) describes, “between the familiar and the strange, between feelings of proximity and feelings of distance” which underlies “every encounter with the past” (p. 5). Lowenthal (Citation2000, p. 64) also discusses this tension as a negotiation between hindsight on one hand and familiarity on the other hand. To cultivate sensitivity toward the past, students engage in experiencing historical temporality, but this experience involves negotiating the presence of the past (Author), which on one hand means to experience the past as distant, that is, to become aware of difference, change, and contingency throughout time, and on the other hand to experience the past as close, that is, to develop a sense of familiarity and involvement with the past and its remnants (). In our classroom experiment, we implemented this guideline by dedicating the first three lessons of the unit plan to activities that required students to both to cognitively grasp the distinct historical context of the war, including its causes and consequences, and to affectively respond to the past by seeing, feeling, and caring for the people and events that marked the period in big and small ways.

Experience the past as distant

To help students make meaning of the distance in time between the present and the past, learning goals and activities should have them work on their understanding of chronology, thus familiarizing them with conventional dating systems and time-related historical vocabulary, using timelines to help them place events, people, places, objects, periods in a temporal sequence, and helping them identify features of periods and draw comparisons between how people lived in different periods time (Dawson, Citation2004; De Groot-Reuvekamp et al., Citation2014; Hodkinson, Citation2009; Levstik & Barton, Citation2008; Stow & Haydn, Citation2000). It also includes working on students’ understanding of second-order concepts related to time in history, such as change, causation, duration, and concurrence (Blow, Citation2011; Blow et al., Citation2012) as well as their everyday language and cultural tools for grasping similarities and differences in material culture and social patterns of past and present ordinary life (Barton, Citation2002; Levstik & Barton, Citation2008). Additionally, to make meaning of the distance in time between the past and the present, it is useful for students to cultivate temporal orientation, that is, build a usable and comprehensive associative framework of temporal references or a “usable past,” which is most effective when enhanced by concept maps, visual and narrative cues, and evocative era descriptions, and accessed by cognitively leaping between references to the past and their present understandings of it (Blow et al., Citation2015; Howson, Citation2007; Lee & Howson, Citation2009; Wilschut, Citation2012).

In practice, Michael tried several things to engage students in negotiating the presence of the past in this way. One of the more salient examples took place during the first lesson. Michael placed printed images on the walls around the classroom. After ten minutes, students placed their desks in the shape of a half circle. Michael then introduced the lesson’s guiding question: “Why, after the costs of World War 1, did nations want to fight or avoid another world war?.” He told students “we won’t answer it yet, you probably have answers” and then gave students instructions for a guided inquiry activity. This consisted of walking around the classroom in groups of four to examine ten different historical sources (images, some with captions) Michael had posted on the classroom walls. Sources included: a map of territorial rearrangements after the Treaty of Versailles, an extract of Hitler’s speech as part of Austria’s annexation in 1938, a photograph of Chamberlain, a political cartoon of Hitler and Mussolini’s marriage, a map of the League of Nation’s development, a photograph of Japanese troops during the invasion of China in 1937, an image of an Ethiopian stamp with Mussolini and Hitler’s portraits on it, a political cartoon with Uncle Sam in the ocean, a short extract from Hitler’s Mein Kampf, and a photograph of Spanish general and dictator Francisco Franco. Students were handed out a worksheet with ten statements that described specific consequences of World War 1 and causes of World War 2 and were asked to complete the worksheet by matching the correct source with each statement. They took about ten minutes to complete the activity. They walked around the class examining the images and sources out loud with each other. The twenty or so minutes remaining of the lesson were spent as a debrief, going over the answers but also elaborating on them to emphasize students’ chronological understanding, their understanding of temporal concepts, and their associative framework of temporal references. Also, in the following lesson, Michael gave a brief lecture about the role of timelines, periodization, and anachronism in relation to World War Two, and in the third lesson, Michael gave a conventional chronological account of the war in a lecture that included a visual presentation with key images and sound effects.

Experience the past as close

To help students personally connect with environments, objects and circumstances that relate to the past, students should be encouraged to see, feel, and respond to the past. Allowing a sense of connectedness in the study of the past does not imply fostering the belief that the past is the same as the present; rather it involves establishing familiarity with the past, the ease to imagine what things were like and what historical events might have meant for people living them, and also to have certain feelings, beliefs, attitudes and emotions with regards to what happened in the past and how that transfers to the present. As Rosenzweig (Citation2000) suggests, “the most powerful meanings of the past [come] out of the dialogue between the past and the present, out of the ways the past can be used to answer pressing current questions about relationships, identity, mortality, and agency” (p. 280). This is reflected in the results of my literature review (Popa, Citation2022). Indeed, creating pedagogical encounters with historical artifacts, oral and family histories, art that portrays historic events, and public heritage and historical sites, for example, seems to help students feel touched or moved by the past in various ways, because it allows them to manipulate and marvel at ordinary and everyday objects of material and immaterial historical inheritance (Gosselin & Livingstone, Citation2016; Henderson & Levstik, Citation2016; Jones, Citation2016; Llewellyn & Ng-A-Fook, Citation2019). Teaching about aspects that seem more real to students, such as daily life, children or local history (Ashton & Hamilton, Citation2009; Conrad et al., Citation2013; Rosenzweig & Thelen, Citation1998), teaching about how people experienced dramatic or extreme events (Barton & Levstik, Citation2004) and teaching about controversial and sensitive issues in history that require students to make moral judgments of past actions and reflect upon contemporary ethics and their own prejudices (Ammert et al., Citation2017; Chinnery, Citation2013; Milligan et al., Citation2019; Simon, Citation2004), can also promote personal and affective connections to the past.

In practice, our unit sought to engage students in negotiating the presence of the past in this way and did so especially well in a show-and-tell activity that took place at the start of the second lesson. As homework before this lesson, students were required to find an object or image related to World War Two and to describe in a few words: (a) what it is, (b) what they know or do not know about it, (c) why they chose it, and (d) what emotions they feel when they see or think about it. Students were informed they could choose an old photograph, a letter, a postcard or any other object at home that belonged to someone they know or from the International Museum of World War II’s online collection. They were expected to bring their item, or an image of it, to class. In groups of three, students discussed their items and shared with each other their answers to those four questions. Some students walked around to talk or listen to other groups, while Michael walked around to listen to conversations. This was followed by a debrief session during which three students informally shared with the rest of class their items and their answers to the questions. These items were a copy of the video game Call of Duty, the photo-diary of the uncle of a student’s grandfather who was a British soldier in Norway during the war, and a copy of a photo of the Enola Gay, the Boeing B-29 bomber that dropped the first atomic bomb. Michael then asked students to share their views on the following question: “Do the lives of those who lived in other times matter? How can we understand their lives if we weren’t there to see for ourselves?.” He then explained to them how manipulating and examining artifacts is an opportunity to see “the real stuff” of the past and “interact with it.” This activity was followed by a guided inquiry activity with actual artifacts and documents from World War Two that a local museum educator had been invited to bring to Michael’s class for a special activity.

Guideline 2. Inquire into the past with the help of habits of mind

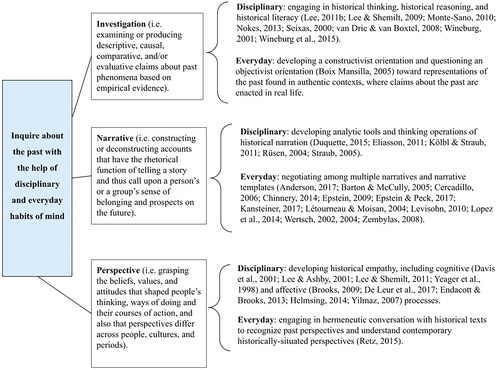

While making meaning of the experience of historical temporality helps to engage with the past that is everywhere around us, we cannot begin to grasp and credibly reconstruct what went on in the past or how things came to be the way they are without historical understanding. To represent and organize meanings about the past in a coherent and communicable way, we need to interpret historical material, or actively turn “what happened” into history. More precisely, this involves inquiring about the past using habits of mind. The term habit of mind goes beyond and encompasses what some view as distinct ways of thinking that historians employ, such as concepts, principles, thinking skills, and cognitive tasks. A habit of mind refers, more generally, to an intellectual disposition that has been developed over time and in social context for the purpose of understanding; it consists of a thought pattern that directs one’s attention and facilitates the perception, comprehension, and evaluation of information. An individual acquires a habit of mind from exposure to existing practices and norms, both in the discipline and in everyday life, and continues to form it through practice. There are mainly three habits of mind at play in developing historical understanding: investigation, narrative and perspective (Popa, Citation2022; ). In our classroom experiment, we implemented this guideline by dedicating five lessons that put students in situations where they had to inquire into the past using these habits of mind.

Investigation

For one, students develop the ability to understand the past by approaching it in terms of an investigation. While the meaning of the term itself is debated, it basically refers to ways of reasoning with sources of information about the past so as to examine or produce descriptive, causal, comparative, and/or evaluative claims about past phenomena based on empirical evidence. Developing students’ ability to reason in such ways is seen by many as one of the most important goals of history education. As Seixas (Citation1999) argues, “good history teaching […] exposes the process of constructing warranted historical accounts so that students can arrive at their own understandings of the past through processes of critical inquiry” (p. 332). Scholars have developed frameworks, empirically based models of progression, and heuristics for historical thinking, historical reasoning, and historical literacy, which are meant for students to gain proficiency in accessing and processing historical information and in constructing knowledge; these generally revolve around educational aims and practices that encourage students to ask appropriate questions, read and contextualize sources, adequately handle substantive and second-order concepts, and comprehend the issues and criteria involved in formulating and substantiating claims (Lee, Citation2011b; Lee & Shemilt, Citation2009; Monte-Sano, Citation2010; Nokes, Citation2013; Seixas, Citation2000; van Drie & van Boxtel, Citation2008; Wineburg, Citation2001; Wineburg et al., Citation2015). By using investigation to understand the past, learners can be mentored and guided into the cognitive conventions of inquiry in the domain (Boix-Mansilla, Citation2005; Lee & Shemilt, Citation2004; VanSledright & Afflerbach, Citation2005), and the metacognitive strategies required for studying texts and solving problems (Poitras & Lajoie, Citation2013). Importantly, understanding the past via investigations depends on how young people encounter traces and accounts of the past in everyday life, whether at school, in popular culture, family stories, news and social media, collective traditions, and public art and architecture. As Lowenthal (Citation2015) suggests, students come across representations of history in several spheres of life, and though they can be quite different and even conflicting, they nonetheless coexist in various ways. Though analyzing sources, formulating and substantiating claims, and producing explanations can promote student historical understanding, teachers need to be aware of their learners’ underlying beliefs about the nature of historical knowledge and inquiry and help them develop a “constructivist” epistemological orientation toward historical accounts, as opposed to an “objectivist” perspective or everyday notion of history as the reproduction of the past (Boix-Mansilla, Citation2005). To support this, teachers’ themselves must endorse beliefs and practices about the interpretive nature of history (Hartzler-Miller, Citation2001; Lévesque & Zanazanian, Citation2016; van Hover et al., Citation2016).

In practice, our unit encouraged students a few times to inquire into the past with the help of investigations. A notable instance of this occurred during the fourth lesson. The activity consisted of examining a given historical source’s usefulness as evidence to answer the question “What was life like for U.S. soldiers at war overseas?.” The instructions provided in the portfolio asked students to imagine that they were helping their grandmother clean out her basement, and found a shoebox containing items from World War Two, which she had kept as memories of her soldier boyfriend but was now unable to recall what his experience might have been. Students were also given a handout that included: an image of their historical source; a brief description about who created it, when it was created, why it was created, and the historical context of its creation; and prompts for judging the authenticity and credibility of the source. Each group of students received one of the following historical sources: a propaganda poster illustrating a muscular topless man on the battlefield with the caption “Man the guns - Join the Navy” produced in 1942; a photograph of a soldier in uniform feeding and brushing a young donkey with a dog next to him; an extract from a soldier’s letter from 1942 to his mother; a photograph, originally printed by LIFE Magazine in 1943, of dead soldiers lying on a beach; a photograph of an African-American Lieutenant with a bandage around his head, clearly injured, but standing and discussing with another military man with civilians in the background; and an extract from the diary of a soldier recounting events from D-Day, June 6, 1945, and his day-to-day life in the twenty days following the event. Students were given eight minutes to conduct the inquiry and respond to the worksheet questions in groups of four, before sharing their results with the rest of class as part of a lively debrief discussion that lasted about 25 minutes. It was followed by Michael’s explanation of the difference between traces and accounts, tips for analyzing primary and secondary sources, as well as the role of evidence in building knowledge about what happened in the war.

Narrative

A second interpretive habit of mind that helps students understand the past is narrative. Narratives are accounts that have a rhetorical function (i.e., telling a story) and thus call upon a person’s or a group’s sense of belonging and prospects on the future. There are two main themes for narrative as a habit of mind in history education. On one hand, students can be taught analytic tools and thinking operations of historical narration (Kölbl & Straub, Citation2011; Rüsen, Citation2004; Straub, Citation2005), which can be viewed as the “operations by which the human mind realizes the historical synthesis of the dimensions of time simultaneous with those of value and experience lie in narration: the telling of a story” (Rüsen, Citation2004, p. 69). Because the ways in which historical narration realizes its orienting function has implications for a persons’ moral consciousness, teachers can pay attention to how students identify with certain historical narratives and accordingly the moral values and moral reasoning they endorse, and thus support learners’ cognitive development in Rüsen’s narrative sense-making procedures, from more primary types that stress “traditions” or “exempla,” to more disciplinary types that stress “critique” or “change and difference” (Duquette, Citation2015; Eliasson, Citation2011). In addition to cognitive narration capacities, students can be taught on the other hand to examine the sociocultural nature of the narrated stories they know and tell as everyday interpreters of history. Students indeed come to their history classes possessing knowledge of stories, often about the nation they belong to, which they encountered throughout their lifetime from a wide array of sources, such as textbooks, teachers, family and community members, politicians, memoirs, novels, films, videos, exhibitions, historical monuments, newspaper articles, social media, and so on (Levisohn, Citation2010; Wertsch, Citation2002, Citation2004). These stories, whether big or small, vie for their attention against the ones they study, scrutinize and construct as part of their lessons. Teachers can help their students to negotiate among these various, multiple and sometimes competing narratives and narrative templates, by asking students to examine the stories they know and/or believe, how they are performed in the public realm, the form and function of storytelling, the political and ideological position of the storyteller, and how collective memory attributes significance to certain aspects while leaving out others and thus how a story might be commemorated differently (Anderson, Citation2017; Barton & McCully, Citation2005; Cercadillo, Citation2006; Chinnery, Citation2014; Epstein, Citation2009; Epstein & Peck, Citation2017; Kansteiner, Citation2017; Létourneau & Moisan, Citation2004; Lopez et al., Citation2014; Zembylas, Citation2008). Focusing on the sociocultural process of negotiation of multiple narratives, by contrast to cognitive psychological narrative meaning making, teachers can engage students in discussions and debates that allow their diverse voices and backgrounds to take center stage.

In practice, Michael and I designed activities in which students were asked to inquire into the past with the help of narrative. One particular guided inquiry activity stands out, which took place during the fifth lesson of the unit. It focused on “unpacking Rosie the Riveter.” To set up this activity, Michael first played a three-minute video clip on the white screen from History.com called American Women in World War II: Rosie the Riveter, which students watched in silence. The video introduced the origins and significance of the image, and thus represented the “typical Rosie narrative” that was described in the portfolio as follows: “WWII represented a major turning point for American women who eagerly supported the war effort, proving to themselves and the country they could do a “man’s job” and could do it well. Economic opportunities abounded for women willing and able to seize them during the war, and paved the way for female-empowerment social movements that would take center stage in postwar generations.” Then, Michael projected the famous Rosie the Riveter poster on the big screen, which represented both a historical document and a familiar symbol of American culture. Students were asked to do a think-pair-share analysis of the image and to reflect on what it symbolizes. About a minute later they engaged in a whole-class open-ended discussion about the image. Students reported their thoughts and observations and Michael participated in the exchange but also scaffolded student thinking. Students did not seem worried about answering incorrectly but were rather interested in uncovering details about the image. Several even seemed eager to talk about the image’s meaning as a propaganda poster, to situate it in its context and to contrast it with a poster they examined in the prior lesson. Having hooked students through this activity that lasted about thirteen minutes, Michael proceeded to read out loud short passages of four oral history testimonies of women who had experienced the war first-hand, both on the combat and home front, as well as extracts from three secondhand interpretations about women’s wartime experience. The extracts were also projected on the big screen while Michael was reading them. It took him twelve minutes. During this time, students listened and wrote down information that challenged the typical Rosie narrative. Then, for approximately eight minutes, Michael and his students engaged in a whole class debrief about what they wrote down and tried to answer the questions “how are historical stories different from other stories, and who decides what the stories are?.” After the debrief session, Michael asked his students to read a three-page explanation about the elements that typically constitute a narrative, how different societies rely on narratives and storytelling to establish their collective identities, the importance of the selective process underlying historians’ narrative interpretations of events, and the dynamics between dominant narratives and counter-narratives in US culture since 1945.

Perspective

The third interpretive habit of mind that can help students understand the past is perspective (Popa, Citation2022). To meaningfully interpret historical material, a rigorous intellectual effort is needed to grasp personal and social perspectives (i.e., the beliefs, values, and attitudes that shaped people’s thinking, ways of doing and their courses of action) and also that perspectives differ across people, cultures, and periods. The notion that people from the past had needs, feelings and aspirations due to circumstances that differ from those of today is indeed a challenge and makes explaining past people’s decisions, practices and institutions a risky task (Lee & Ashby, Citation2001). Over the past decades, researchers have thus been defining historical empathy, examining how students display it, and suggesting instructional methods and strategies to foster it in the history classroom. For some, historical empathy is a distinctly rational ability (Davis et al., Citation2001; Lee & Ashby, Citation2001; Yeager et al., Citation1998) and developing it involves progression through developmental cognitive levels of explanatory reasoning capacities from novice to expert, so that students learn not to judge past beliefs and actions as irrational, unreasonable, evil, or backward (Lee & Shemilt, Citation2011). For others, the view of historical empathy as purely analytic is problematic because it discounts affective processes (Brooks, Citation2009; De Leur et al., Citation2017; Endacott & Brooks, Citation2013; Helmsing, Citation2014; Yilmaz, Citation2007). Yet, situations that ask students to put themselves in a past person’s shoes do not, according to de Leur, van Boxtel & Wilschut (Citation2017), “necessarily have to lead to excessive fantasy” (p. 16). By implicating their own emotions, such as joy, pity or surprise in the attempt to interpret how historical actors experienced their lives, students can feel motivated to contextualize the past (Logtenberg et al., Citation2011) and also to articulate, examine, challenge, and develop their own emotional world (Husbands & Pendry, Citation2000). Similarly, by invoking feelings related to guilt, injustice and responsibility toward past crimes, tragedies, wrongdoings, trauma, and so on, students can engage in serious moral reasoning about “who if any[one] was accountable for the unjust actions in the past, who has a moral right to speak on behalf of the perpetrators and the victims of past injustices now, and can people of a distant past be judged by today’s moral standards, and on what premises?” (Löfström & Myyry, Citation2017, p. 69). Thus, the empathetic process is “fluid and cross-functional” and integrates “cognitive, emotional, moral and social structures,” as Retz (Citation2015) argues. To empathize in history in this integrative way, students can engage in a hermeneutical “conversation” or a “dialogical exchange” with sources (Retz, Citation2015, p. 224) that helps them recognize past perspectives, how their own position both shapes and is shaped by the encounter and understanding of a historical other. In sum, teachers can encourage students to imagine themselves in the lived experiences, situation or actions of the past, to try to relate to others’ values and emotions, to explain them in reference to the epoch’s “mentalités” or “forms of life” in which material, social and symbolic cultures are “symbiotically linked and mutually sustaining” (Lee & Shemilt, Citation2011, pp. 41–48), and to recognize that their own perspectives are historically and culturally situated without trying to deny them. Simulations, dialogic questioning, and written essay tasks constitute meaningful learning experiences in this respect (DiCamillo & Gradwell, Citation2012).

In practice, Michael and I designed several learning experiences that engaged students in dealing with historical questions and interpreting historical material by reflecting in terms of perspective. One especially insightful experience, a guided inquiry activity, took place during the eighth lesson, which Michael opened with the questions “Why did people think or act the way they did, what values, beliefs, worldview, motivations, and practices drove them, and how do our own ways of thinking and doing influence how we understand them?.” The activity was designed as a role-playing discussion with the aim of exploring the decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki from multiple perspectives. Michael set this activity up, first, by lecturing about different perspectives, expressed during the war period, in favor and against the bombing. He projected a table on the white screen and explained six different arguments, three for each side. Then Michael handed out different worksheets to students. On each handout was an extract from a primary source and questions to reflect on the author’s perspective. In total, there were twenty-four sources and four groups of perspectives. Three handouts provided a primary source that showed the Japanese point of view: an article published in the Nippon Times in 1945, an eyewitness testimony by Yoshitaka Kawamoto of the bombing of Hiroshima; and the Imperial Rescript of Surrender speech by Emperor Hirohito. Three handouts provided a primary source that showed the point of view of ordinary Americans: an oral history interview in 1995 with Nancy Potter who worked as a volunteer during WWII in a hospital in Boston to relieve civilian nurses; a letter written by William M. Hinds to the editors of Life magazine, and an article by Lester Bernstein published in the New York Times in 1965. Three more handouts provided a primary source that showed the point of view of scientists and others involved in the Manhattan project: The Franck Report, The Recommendations on the Immediate Use of Nuclear Weapons, and an interview in 2003 with Joseph Rotblat who was a Manhattan Project scientist. Finally, three handouts provided a primary source that showed a political and military point of view: a paper published in The Harpers in 1947 written by Henry L. Stimson who was Secretary of War from 1940 to 1945, the Memoirs (1955) of Harry S. Truman, and the memoirs (I Was There, 1950) of Admiral William E. Leahy. Individually, students first examined their source and answered the questions on the handout. Then, Michael asked students who had the same perspective to come together as a group and to share their thoughts about what they had just read with their classmates. Then each group presented their sources and group’s perspective. During the debrief, Michael encouraged his students to see the nuance and complexity of each perspective. Michael wrapped up the discussion by asking students who they thought was accountable for the dropping of the bomb.

Guideline 3. Build a sense of historical being

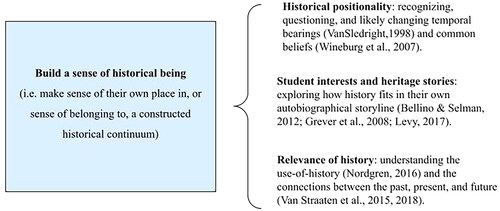

The third and final ability of historical consciousness is self-representation in relation to history. In our unit, we dedicated two lessons to this. Meaningful History holds that making meaning about the past and history can, and often does, involve making meaning about who we are, where we are situated in time, and how we act as participants in ongoing history. Such meaning is shaped by needs for orientation in present daily life. As such, historical meaning making is not only a matter of “knowing,” it is also a matter of “being” (Seixas, Citation2012). To view themselves in relation to ongoing historical developments for the purpose of navigating their everyday life, students engage in building a sense of historical being (Popa, Citation2022; ).

A notable dimension of this has to do with becoming aware of “historical positionality,” which is, as VanSledright (Citation1998) describes, a frame of reference that is comprised of culturally-mediated but internalized memories, codes, and contexts that influences what images, ideas, and conceptions about the past students bring to the learning context. These “temporal bearings” must be taken into account in the history classroom, since they constitute prior knowledge and background experience to build on in the process of developing historical understanding; teachers can thus pose questions that encourage learners to interrogate and self-reflect on the temporal bearings of their identities and life stories and can include in their teaching disorienting dilemmas or issues that raise perplexity or doubt in this respect (VanSledright, Citation1998). Teachers can also make more room in their instruction for “common beliefs,” that is, widely shared cultural references and beliefs students have acquired from home, school, their community and popular culture, such as movies, photographs, and family stories (Wineburg et al., Citation2007). To teach in this way, educators need to value a culturally responsive learning environment and recognize that historical meaning making occurs not only at the hands of historians, but also at an intergenerational level in the complex interplay of “forces that act to historicize today’s youth” (Wineburg et al., Citation2007, p. 40).

Indeed, researchers have been focusing on forms of pedagogy that are community-based or support more personalized and curiosity-driven forms of engagement. Some promote the integration of film media (Paxton & Marcus, Citation2018), digital simulations and games (Wright-Maley et al., Citation2018), and museums and public sites (Stoddard et al., Citation2018) in history lessons. Some suggest incorporating heritage education activities that invite students to “place themselves in a longer intergenerational historical narrative” (Clark, Citation2014, p. 93) and to explore how history fits in their own autobiographical storyline (Bellino & Selman, Citation2012; Grever et al., Citation2008; Levy, Citation2017). Some support relating the history curriculum to the heritage students are familiar with as members of ethnic, racial and cultural groups (Barton & McCully, Citation2005, p. 20; Epstein, Citation2009; Levstik, Citation2008; Peck, Citation2010; Zanazanian, Citation2015) and to explore identity issues and student interests in darker aspects of national histories and minority voices (den Heyer & van Kessel, Citation2016; Grever et al., Citation2011). Some also consider the relevance of exploring disjunctive epistemological and ontological stances toward the past and scrutinizing the power dynamics in western/white historical knowledge production (King, Citation2019; Seixas, Citation2017). Some suggest specific teaching strategies to help students see the relevance of learning history, namely “enduring human issues,” “long-term developments” and “historical analogies” (van Straaten et al., Citation2016; Van Straaten et al., Citation2018). What these various pedagogical approaches have in common is that they emphasize historical culture that students likely encounter outside the classroom in order to engage them to communicate something about who they are, what they like, what they believe in, the lives they are living, and the world they live in.

In practice, our unit tried to achieve this in several ways. For example, there were two homework assignments that required students to brainstorm ways in which the history covered by the unit relates to them. The first consisted of listing elements of history that connect to who they are and the life they are living or expect to live, taking into account their background (e.g., family, community, home, life story), their interests (i.e., what and who they care about), their thoughts and feelings about the world, the values and principles that guide their actions, their fears and dreams, and their relationships with others. It encouraged them to include any of the following: events (e.g., battles, turning points in the war, events in a person’s life); individuals or groups of people (e.g., political leaders, someone they know, a social group, someone famous); objects (e.g., that belong to them or someone they know, that they have seen in a museum or in a movie); places they have visited or heard about (e.g., historic sites, memorials); themes, developments, or issues that extend over many years (e.g., war and peace, social justice, scientific discoveries and technological innovations, specific ideologies, food, work, medical treatments). Students were asked to represent those connections in a diagram, using lines or arrows to show links or influences among different elements and different shapes and colors to signal different categories of elements. The second brainstorm task consisted of picking one connection from that diagram and coming up with different ways in which that connection shapes their sense of who they are as individuals and as members of social groups, that is, how they define themselves and how others define them. They were encouraged to brainstorm and concept map along the lines of: how they think, how they behave, where they stand on big and small issues, what choices they make, and their views on the future.

Final remarks

Education begins with a vision of learning, but how to concretely realize that vision can be rather tricky. The vision proposed in this article, to summarize, is to engage in three meaning-making processes (i.e., experiencing historical temporality, interpreting historical material, and orienting in practical life to foster) to cultivate three abilities for making meaning (i.e., sensitivity toward the past, understanding of the past, and self-representation in relation to history). The processes help students build and negotiate meaning from experience and the abilities help students be and become their own person in reference to their surrounding world. Educators can facilitate those processes, respectively, by putting students in situations where they negotiate the presence of the past, inquire into the past with the help of habits of mind, and build a sense of historical being. Such learning is meant to make students better disposed to make the historical past their own. What all this might actually look like in a particular setting with specific people will depend on the learners, the teacher, the content, the goals, the activities, the resources, and the context.

Indeed, enacting the vision of learning promoted by Meaningful History will look differently in each classroom precisely because it endorses a conception of learning as meaning making rather than competence development. In no way are these conceptions opposed or mutually-exclusive; in fact, Meaningful History incorporates several historical thinking skills and second order concepts that are promoted by the competency approach. Where they differ is not so much in their content as in their purpose. Emphasizing meaning making is arguably more appropriate to promote sense-making and engagement with the learning content, whereas competence development can more aptly promote mastery of the content according to disciplinary structures and norms. A pedagogy that focuses on meaning making could contribute to pushes for curriculum change, as well as to finding meaningful ways of teaching the subject and producing learning experiences that are more relevant to students’ lives (De Julio, Citation2019; van Straaten et al., Citation2016).

The extent to which Meaningful History is practical and effective as a pedagogical approach needs to be better understood, ideally through educational design investigations that enact it and fine-tune it to meet particular classroom needs and purposes. A first area of interest for the research community, in this sense, would be to explore how learning occurs when teaching utilizes Meaningful History in different countries, examining similarities and differences. Even within the same country or within the same school district, exploring the influence of contextual features on the use of Meaningful History could also reveal valuable insights. What happens in terms of learning and instructional development, for instance, when students resist new teaching methods that push them out of their comfort zone? Or when there are numerous cultural, ethnic and class differences or intellectual abilities within the same student group, and multiple modes of engagement are required to reach all students? Or when the state or school curriculum discourages students, especially from historically underrepresented groups, to learn to make meaning for themselves about the distribution of power and authority within the culture? Another interesting avenue to explore is the extent to which the meaning-making processes and abilities of Meaningful History are interdependent or more precisely how they influence each other. And what factors and conditions are required for change in historical consciousness to happen? How should change in this disposition, as a result of learning, be assessed? Future research in these different directions would help to shed light on ways in which Meaningful History could be applied to a variety of learning environments.

Acknowledgements

I thank Michael and his students for opening their classroom to my inquiry. I also thank Paul Zanazanian (McGill University), Lynn Butler-Kisber (McGill University), Kenneth Nordgren (Karlstad University) and Veronica Boix-Mansilla (Harvard University) for insightful discussions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ammert, N., Edling, S., Löfström, J., & Sharp, H. (2017). Bridging historical consciousness and moral consciousness: Promises and challenges. Historical Encounters, 4(1), 1–13.

- Anderson, S. (2017). The stories nations tell: Sites of pedagogy, historical consciousness, and national narratives. Canadian Journal of Education | Revue Canadienne de L’éducation, 40(1), 1–38.

- Ashton, P., & Hamilton, P. (2009). Connecting with history: Australians and their pasts. In P. Ashton & H. Kean (Eds.), People and the pasts: Public history today (pp. 23–41). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barton, K. C. (2002). “Oh, that’s a tricky piece!”: Children, mediated action, and the tools of historical time. The Elementary School Journal, 103(2), 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1086/499721

- Barton, K. C., & Levstik, L. S. (2004). Teaching history for the common good. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Barton, K. C., & McCully, A. W. (2005). History, identity, and the school curriculum in Northern Ireland: An empirical study of secondary students’ ideas and perspectives. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 37(1), 85–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000266070

- Becker, C. (1932). Everyman his own historian. The American Historical Review, 37(2), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.2307/1838208

- Bellino, M. J., & Selman, R. (2012). The intersection of historical understanding and ethical reflection during early adolescence: A place where time is squared. In M. Carretero, M. Asensio, & M. Rodriguez-Moneo (Eds.), History education and the construction of national identities (pp. 189–202). Information Age Publishing.

- Bentley, T. (2012). Learning beyond the classroom: Education for a changing world. Routledge.

- Blow, F. (2011). “Everything flows and nothing stays”: How students make sense of the historical concepts of change, continuity and development. Teaching History, 145, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01591-8

- Blow, F., Lee, P., & Shemilt, D. (2012). Time and chronology. Conjoined twins or distant cousins? Teaching History, 147, 26–34.

- Blow, F., Rogers, R., Shemilt, D., & Smith, C. (2015). Only connect: How students form connections within and between historical narratives. In A. Chapman & A. Wilschut (Eds.), Joined-up history: New directions in history education research (pp. 279–315). Information Age Publishing.

- Boix-Mansilla, V. (2005). Between reproducing and organizing the past: Students’ beliefs about the standards of acceptability of historical knowledge. In R. Ashby, P. Gordon, & P. Lee (Eds.), International review of history education (Vol. 4, pp. 98–115). Routledge.

- Boix-Mansilla, V., & Gardner, H. (2007). From teaching globalization to nurturing global consciousness. In M. M. Suarez-Orozco (Ed.), Learning in the global era: International perspectives on globalization and education (pp. 47–66). University of California Press.

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A., & Cocking, R. (1999). How people learn: Mind, brain, experience, and school. National Research Council.

- Brooks, S. (2009). Historical empathy in the social studies classroom: A review of the literature. Journal of Social Studies Research, 33(2), 213–234.

- Bruner, J. S. (1996). The culture of education. Harvard University Press.

- Carretero, M. Berger, S., & Grever, M. (Eds.). (2017). Palgrave handbook of research in historical culture and education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cercadillo, L. (2006). ‘Maybe they haven’t decided yet what is right:’ English and Spanish perspectives on teaching historical significance. Teaching History, 125, 6–9.

- Chapman, A. & Wilschut, A. (Eds.). (2015). Joined-up history: New directions in history education research. Information Age Publishing.

- Chinnery, A. (2010). “What good does all this remembering do, anyway?” On historical consciousness and the responsibility of memory. Philosophy of Education, 2010, 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2013.878083

- Chinnery, A. (2013). Caring for the past: On relationality and historical consciousness. Ethics and Education, 8(3), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2013.878083

- Chinnery, A. (2014). On Timothy Findley’s The Wars and classrooms as communities of remembrance. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 33(6), 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-014-9406-7

- Clark, A. (2014). Inheriting the past: Exploring historical consciousness across the generations. Historical Encounters, 1(1), 88–102.

- Clark, A., & Grever, M. (2018). Historical consciousness: Conceptualizations and educational applications. In S. A. Metzer & L. M. Harris (Eds.), The Wiley international handbook of history teaching and learning (pp. 177–201). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Clark, A., & Peck, C. (2019). Contemplating historical consciousness. Notes from the field. Berghahn Books.

- Conrad, M., Ercikan, K., Friesen, G., Létourneau, J., Muise, D., Northrup, D., & Seixas, P. (2013). Canadians and their pasts. University of Toronto Press.

- Damasio, A. (1999). The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. Harcourt.

- Daniels, H., Lauder, H., & Porter, J. (Eds.). (2012). Educational theories, cultures and learning: A critical perspective. Routledge.

- Davis, O. L., Yeager, E. A., & Foster, S. J. (Eds.). (2001). Historical empathy and perspective taking in the social studies. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Dawson, I. (2004). Time for chronology? Ideas for developing chronological understanding. Teaching History, 117, 14–24.

- De Groot-Reuvekamp, J. M., Van Boxtel, C., Ros, A., & Harnett, P. (2014). The understanding of historical time in the primary history curriculum in England and the Netherlands. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 46(4), 487–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2013.869837

- De Julio, A. (2019, April 15). How can we truly bring history to life? [Paper presentation]. Reflections and Takeaways from the Annual Conference 2019. EuroClio. https://www.euroclio.eu/tag/bringing-history-to-life/

- De Leur, T., Van Boxtel, C., & Wilschut, A. (2017). ‘I saw angry people and broken statues’: Historical empathy in secondary history education. British Journal of Educational Studies, 65(3), 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2017.1291902

- den Heyer, K., & van Kessel, C. (2016). Evil, agency, and citizenship education. McGill Journal of Education, 50(1), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.7202/1036107ar

- DiCamillo, L., & Gradwell, J. (2012). Using simulations to teach middle grades U.S. history in an age of accountability. Rmle Online, 35(7), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404476.2012.11462090

- Duquette, C. (2015). Relating historical consciousness to historical thinking through assessment. In E. Ercikan & P. Seixas (Eds.), New directions in assessing historical thinking (pp. 51–63). Routledge.

- Eliasson, P. (2011). In search of historical consciousness – A classroom research project of history education. In K. Nordgren, P. Eliasson, & C. Rönnqvist (Eds.), The processes of history teaching. An international symposium held at Malmö University, March 5th–7th 2009 (pp. 43–67). Karlstad University Press.

- Eliasson, P., Alven, F., Yngveus, C. A., & Rosenlund, D. (2015). Historical consciousness and historical thinking reflected in large-scale assessment in Sweden. In K. Ercikan & P. Seixas (Eds.), New directions in assessing historical thinking. (pp. 171–182). Routledge.

- Endacott, J., & Brooks, S. (2013). An updated theoretical and practical model for promoting historical empathy. Social Studies Research and Practice, 8(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/SSRP-01-2013-B0003

- Epstein, T. (2009). Interpreting national history: Race, identity, and pedagogy in classrooms and communities. Routledge.

- Epstein, T., & Peck, C. (Eds.). (2017). Teaching and learning difficult histories in international contexts: A critical sociocultural approach. Routledge.

- Giroux, H. A., Freire, P., & McLaren, P. (1988). Teachers as intellectuals: Toward a critical pedagogy of learning. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Gosselin, V., & Livingstone, P. (2016). Introduction. In V. Gosselin & P. Livingstone (Eds.), Museums and the past: Constructing historical consciousness (pp. 3–17). UBC Press.

- Grever, M., & Adriaansen, R. J. (2019). Historical consciousness: The enigma of different paradigms. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(6), 814–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2019.1652937

- Grever, M., Haydn, T., & Ribbens, K. (2008). Identity and school history: The perspective of young people from the Netherlands and England. British Journal of Educational Studies, 56(1), 76–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2008.00396.x

- Grever, M., Pelzer, B., & Haydn, T. (2011). High school students’ views on history. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(2), 207–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2010.542832

- Hartzler-Miller, C. (2001). Making sense of the “best practice” in teaching history. Theory & Research in Social Education, 29(4), 672–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2001.10505961

- Helmsing, M. (2014). Virtuous subjects: A critical analysis of the affective substance of social studies education. Theory & Research in Social Education, 42(1), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2013.842530

- Henderson, A. G., & Levstik, L. S. (2016). Reading objects: Children interpreting material culture. Advances in Archaeological Practice, 4(4), 503–516. https://doi.org/10.7183/2326-3768.4.4.503

- Hodkinson, A. (2009). To date or not to date, that is the question: A critical examination of the employment of subjective time phrases in the teaching and learning of primary history. History Education Research Journal, 8(2), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.18546/HERJ.08.2.04

- Howson, J. (2007). Is it the Tuarts and then the Studors or the other way round? The importance of developing a usable big picture of the past. Teaching History, 127, 140–147.

- Husbands, C., & Pendry, A. (2000). Thinking and feeling. Pupils’ preconceptions about the past and historical understanding. In J. Arthur & R. Phillips (Eds.), Issues in history teaching (pp. 125–135). Routledge.

- Illeris, K. (2014). Transformative learning and identity. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jarvis, P. (2009). Learning to be a person in society. Routledge.

- Jarvis, P. (2018). A comprehensive understanding of human learning. In K. Illeris (Ed.), Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists… In their own words (2nd ed., pp. 15–28). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

- Jones, S. (2016). Unlocking essences and exploring networks: Experiencing authenticity in heritage education settings. In C. Van Boxtel, M. Grever, & S. Klein (Eds.), Sensitive pasts? Questioning heritage in education (pp. 130–152). Berghahn Books.

- Kansteiner, W. (2017). Film, the past, and a didactic dead end: From teaching history to teaching memory. In M. Carretero, S. Berger, & M. Grever (Eds.), Palgrave handbook of research in historical culture and education (pp. 169–190). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Karlsson, K. G. (2011). Processing time—On the manifestations and activations of historical consciousness. In H. Bjerg, C. Lentz, & E. Thorstensen (Eds.), Historicizing the uses of the past. Scandinavian perspectives on history culture, historical consciousness and didactics of history related to World War II (pp. 129–143). Transcript Verlag.

- King, L. J. (2019). Interpreting black history: Toward a black history framework for teacher education. Urban Education, 54(3), 368–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085918756716

- Kölbl, C., & Straub, J. (2011). Historical consciousness in youth. Theoretical and exemplary empirical analyses. Forum: Qualitative Social Research/Sozialforschung, 2(3), 9. http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/904

- Körber, A. (2011). German history didactics: From historical consciousness to historical competencies – and beyond? In H. Bjerg, C. Lenz, & E. Thorstensen (Eds.), Historicizing the uses of the past. Scandinavian perspectives on history culture, historical consciousness and didactics of history related to World War II (pp. 145–164). Transcript Verlag.

- Körber, A. (2015a). Historical consciousness, historical competencies – and beyond? Some conceptual development within German history didactics (pp. 1–56). DIPF.

- Körber, A. (2015b). Translation and its discontents II: A German perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 48(4), 440–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1171401

- Körber, A., & Meyer-Hamme, J. (2015). Historical thinking, competencies, and their measurement. In K. Ercikan & P. Seixas (Eds.), New direction in assessing historical thinking (pp. 89–101). Routledge.

- Köster, M., Thunemann, H., & Zulsdorf-Kersting, M. (Eds.). (2014). Researching history education: International perspectives and disciplinary traditions. Wochenschau Verlag.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Laville, C. (2004). Historical consciousness and historical education: What to expect from the first for the second. In P. Seixas (Ed.), Theorizing historical consciousness. (pp. 165–182). Univeristy of Toronto Press.

- Lee, P. (2004). ‘Walking backwards into tomorrow’. Historical consciousness and understanding history. History Education Research Journal, 4(1), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.18546/HERJ.04.1.03

- Lee, P. (2011a). Historical thinking and transformative history. In L. Periklous & D. Shemilt (Eds.), The future of the past. Why history education matters (pp. 129–154). Association for Historical Dialogue and Research.

- Lee, P. (2011b). History education and historical literacy. In I. Davies (Ed.), Debates in history teaching (pp. 77–86). Routledge.

- Lee, P., & Ashby, R. (2001). Empathy, perspective taking and rational understanding. In O. Davis, E. Yeager, & S. Foster (Eds.), Historical empathy and perspective taking in the social studies. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Lee, P., & Howson, J. (2009). Two out of five did not know that Henry VIII had six wives: Historical literacy and historical consciousness. In L. Symcox & A. Wilschut (Eds.), National history standards: The problem of the canon and the future of teaching history (pp. 211–264). Information Age Publishers.

- Lee, P., & Shemilt, D. (2004). “I just wish we could go back in the past and find out what really happened”: Progression in understanding about historical accounts. Teaching History, 117, 25–31.

- Lee, P., & Shemilt, D. (2009). Is any explanation better than none? Over-determined narratives, senseless agencies and one-way streets in students’ learning about cause and consequence in history. Teaching History, 137, 42–49.

- Lee, P., & Shemilt, D. (2011). The concept that dares not speak its name: Should empathy come out of the closet? Teaching History, 143, 39–49.

- Létourneau, J., & Moisan, S. (2004). Young people’s assimilation of a collective historical memory: A case study of Quebeckers of French-Canadian heritage. In P. Seixas (Ed.), Theorizing historical consciousness (pp. 109–128). University of Toronto Press.

- Lévesque, S., & Zanazanian, P. (2016). Developing historical consciousness and a community of history practitioners: A survey of prospective history teachers across Canada. McGill Journal of Education, 50(2–3), 389–412. https://doi.org/10.7202/1036438ar

- Levisohn, J. A. (2010). Negotiating historical narratives: An epistemology of history for history education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 44(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2010.00737.x

- Levstik, L. S. (2008). Crossing the empty places: Perspective taking in New Zealand adolescents’ understanding of national history. In L. S. Levstik & K. C. Barton (Eds.), Researching history education. Theory, method and context (pp. 366–389). Routledge.

- Levstik, L. S., & Barton, K. C. (2008). Researching history education: Theory, method, and context. Routledge.