Abstract

This article examines Swedish civics teachers’ perspectives on difficulties and opportunities that their second-language (L2) students encounter when reading textbook texts in civics. The study is based on individual semi-structured interviews with teachers in Grade 9. Civics teachers report uncertainty about identifying the source of difficulties encountered by L2 students when reading civics texts. A four-field model has been constructed and used to study the complex nature of difficulties with civics texts. The findings suggest that the interdependence among the components in the four-field model, and several additional influential factors, such as teachers’ formal training and their understanding of L2 students’ difficulties, are relevant to consider when supporting L2 students in dealing with challenges posed by civics texts.

1. Introduction

Textbooks in civics are one of the main sources of knowledge and a primary instructional tool for teaching civics in Swedish compulsory schools (Arensmeier, Citation2018). Given the importance of civics texts for students’ knowledge construction and their development into active and informed citizens in a democracy, one could argue that developing reading abilities is an important means to achieve these goals. As Epstein (Citation2020) argues, students as participants in a democracy need not only to read but also to interpret and evaluate vast amounts of information about civics issues retrieved from texts and other sources like the Internet and social media (see also Levine, Citation2007). This line of reasoning could be seen to correspond to the definition of reading literacy as the ability to understand, use, and reflect on written texts in order to develop knowledge and participate actively in society (Mullis & Martin, Citation2019).

Epstein’s reasoning (Citation2020) could also be seen to align with the definition of literacy, grounded in Street (Citation1984) and Gee’s (Citation2001) work, in which literacy is viewed as the process of reading, writing, listening, and oral interaction in a context of socially situated practices. According to this definition of literacy, reading happens in the context of social practices that are historically, socially, and culturally rooted (Frankel et al., Citation2016). This perspective on literacy is relevant when it comes to reading civic texts. The content of civics texts is often presented within a contextual framework that incorporates references to time, places, people, societies, cultures, and events. Consequently, it makes sense to suggest that the understanding of the content in civics texts requires students’ prior knowledge about these references (see also Dong, Citation2017). Another characteristic associated with civics texts is that they often contain abstract and dense content (Chambliss et al., Citation2007). Against this background, it can be suggested that in order to read and critically evaluate the content in civics texts, students would need to develop other sets of reading abilities than basic reading abilities consisting of decoding and understanding single words in texts (see also Wineburg et al., Citation2012).

The perspective on reading abilities described above prompts the idea that reading texts in civics can serve multiple purposes. Developing reading abilities not only facilitates students’ civics learning, but can also enhance students’ engagement, interest, and confidence in using their reading abilities for other meaningful purposes. For instance, reading and learning from texts in civics can support students in communicating their viewpoints, both orally and in written form, when discussing civics issues. In this way, the mutual relationship between civics learning and literacy development could be made clear.Footnote1

The fact that many students who read texts in civics are second-language (L2) learners raises the question of what difficulties L2 students may face when reading and understanding texts in civics. Footnote2 Given the diversity among L2 students in terms of linguistic and cultural backgrounds, levels of language proficiency, and prior knowledge, it is to be expected that they may face different challenges when reading school texts (Schleppegrell & O'Hallaron, Citation2011).

In Sweden, more than 26% of students in compulsory schools carry out their education in a second language, in which, for various reasons, they might have different levels of mastery (SALSA, Citation2021–2022). Moreover, in some schools, newly arrived students are integrated into content-area classes, including civics, without receiving sufficient second-language instruction to prepare them for learning in a language that is a new medium of instruction for them (Nilsson & Bunar, Citation2016; Wedin & Aho, Citation2022). However, despite the presence of L2 students in civics classrooms, there is a limited number of studies elaborating on difficulties that these students may face when reading and understanding texts in civics (Rinnemaa, Citation2023a). Findings from one empirical study, where Swedish L2 students in Grade 9 were asked to describe the challenges they encountered while reading civics texts, indicate that L2 students’ perceived levels of difficulty with texts were largely influenced by various factors and their interplay with each other. Furthermore, the findings suggest that single components, such as L2 students’ insufficient reading abilities or their lack of prior knowledge, were not the only source of difficulties with civics texts. Moreover, L2 students emphasize support from their civics teachers as crucial for comprehending abstract civics texts, as this helps to make the content more concrete (Rinnemaa, Citation2023b). The findings suggest that without teacher support, L2 students run the risk of focusing too much on linguistic aspects of texts, such as looking up difficult words, and missing out on knowledge acquisition (Rinnemaa, Citation2023b).

1.1. Aim and research questions

Considering the important role of teacher support, as underlined by L2 students in the previous study (Rinnemaa, Citation2023b), the aim of this study is to explore L2 students’ opportunities and difficulties with reading and understanding texts in civics from a teacher perspective. By focusing on civics teachers’ views, this study investigates what sources of difficulties, as well as useful resources, emerge in civics teachers’ responses when they talk about their L2 students’ reading and learning from texts in civics. The research questions are as follows:

What language- and content-related difficulties in relation to texts in civics emerge in the civics teachers’ responses when they talk about their L2 students?

What resources do civics teachers consider crucial in general for supporting L2 students’ reading and learning from texts in civics?

2. Previous research

The growing number of L2 students in civics classrooms may bring new challenges for civics teachers. In an ethnographic study aimed at exploring the linguistic aspects of social studies education for L2 students, Wedin and Aho (Citation2022) demonstrate that social studies teachers in the Language Introduction Program in upper secondary school in Sweden adapted their teaching to L2 students by simplifying their instructional methods and the content of textbooks. As a result, the knowledge presented to L2 students was simplified and the prepared lessons and exercises failed to meet L2 students’ needs. The authors argue that despite the qualifications and experiences of the social studies teachers, there appears to be a lack of understanding regarding teaching and learning social studies through a second language. For instance, it appeared that teachers preferred to have students with higher Swedish proficiency, while limited support was provided by them to L2 students with lower Swedish proficiency. Furthermore, the findings by Wedin and Aho (Citation2022) indicate that L2 students are perceived “as deficit when it comes to Social Studies, mainly due to lacking Swedish proficiency” (p. 71). These results are noteworthy, particularly considering the primary purpose of the Language Introduction Program, which is to provide newly arrived immigrant students with the knowledge necessary for further studies in mainstream programs. The authors emphasize the importance of focusing on teaching both content-area knowledge and the language required to convey it effectively within social studies classrooms. This could involve supporting students in developing their ability to read, write, speak, and listen in ways that are relevant to social studies, such as understanding academic or disciplinary language used in social studies texts and discussions (Wedin & Aho, Citation2022). Furthermore, Waagaard (Citation2023), in another ethnographic study focusing on teaching and learning of disciplinary literacy in the social studies, indicates that social studies teaching is mainly oral with few occasions of reading factual texts and textbooks. The focus of the lessons appears to be on oral content building, often though discussing questions and processing of words in texts. Moreover, Waaggard’s findings (Waagaard, Citation2023) show that textbooks are rarely used as a foundation for answering questions, providing evidence, or drawing conclusions in response to writing tasks in social studies classrooms. The author underscores the importance of providing support for the development of more formal language, as everyday language is predominantly used both in teaching and in students’ texts (Waagaard, Citation2023).

Mirra (Citation2022) is another researcher who advocates for a closer integration of literacy and civics education. She proposes a concept called “civically engaged literacy,” which suggests that literary texts, in addition to civics texts, can serve as a powerful resource for civics learning. According to her, literary texts have the potential to portray social and political issues within which the authors’ stories are situated. This provides students with opportunities to enhance their understanding of civics while also becoming familiar with the power of the written word in a language that they may still be learning. To achieve this, Mirra (Citation2022) suggests that teachers need to reflect on both the texts they choose and how they teach them, making the selection of texts particularly relevant in this context (see also Mirra & Garcia, Citation2020). Furthermore, the various textual formats that are accessible through digital technology should also be regarded as significant resources for civics learning, where students’ language proficiency plays a crucial role in their ability to access the knowledge offered by these sources (Mirra, Citation2022, see also Jiang, Citation2022).

The significance of language proficiency in acquiring content-area knowledge from texts is evident in research pertaining to the learning of civics by L2 students. Additionally, students’ prior knowledge in relation to the content presented in civics texts is highlighted as another significant factor in their comprehension of civics texts. In their studies, Myers and Zaman (Citation2009) and Deltac (Citation2012) show that civics teachers face new challenges, primarily related to L2 students’ varying levels of proficiency in their first language (L1) and second language (L2), as well as their different levels of prior knowledge concerning civics topics taught in the classroom. Civics teachers in Deltac’s study (Citation2012) report that when they recognize their L2 students’ language-related difficulties, the most common ways of providing support with the language demands of civics texts are decoding and explaining the meaning of difficult words in the texts. However, researchers such as Jaffee (Citation2016, Citation2022) and Dabach (Citation2015) are critical of this way of supporting students, and suggest that L2 students should be trained to understand the content of civics texts without focusing excessively on individual words. The next section presents five challenges with civics texts that are discussed in research.

2.1. Linguistic-oriented and content-oriented aspects of difficulties with civics texts

Although few studies have closely explored civics teachers’ perceptions of L2 students’ difficulties in relation to texts in civics textbooks, it can be observed that difficulties with civics texts appear to be discussed from two main perspectives in research. The first perspective is linguistic-oriented, with particular focus on form, language, and structure in civics texts (e.g., Chambliss et al., Citation2007; Epstein, Citation2020; Kulbrandstad, Citation1998; Rangnes, Citation2019; Reichenberg, Citation2000; Walldén & Nygård Larsson, Citation2022). From a linguistic-oriented perspective, civics texts are studied based on the identification of types of difficult words present in them, the analysis of sentence structures used to present the main themes, and the examination of the cohesion and connections between different parts of the texts. This linguistic-oriented approach allows for a detailed exploration of the language elements and structures within civics texts, providing insights into how they contribute to students’ overall understanding and comprehension of the content in texts.

The second perspective is a content-oriented perspective, which focuses on aspects such as the selection of civics topics within texts and L2 students’ prior knowledge in relation to them. Studies conducted from this perspective, such as the work of Dabach (Citation2015), Dabach et al. (Citation2018), Jaffee (Citation2016, Citation2022), Deltac (Citation2012), Gibson (Citation2017), Di Stefano and Camicia (Citation2018), and Blankvoort et al. (Citation2021), explore how the content of civics texts can impact L2 students’ sense of belonging and inclusion, or alternatively, reinforce feelings of power inequalities and cultural differences among them as readers. However, it is worth noting that separating linguistic-oriented aspects from content-oriented aspects when analyzing the readability issues of civics texts can be challenging, as the two are often related. For instance, when the abstract content of civics texts is made concrete and linked to L2 students’ prior knowledge, the language-related difficulties, such as difficult words and long sentences in texts, seem to be less of a hindrance to understanding of the texts (Rinnemaa, Citation2023b). In her study, Rinnemaa (Citation2023b) demonstrates that there is an interrelation between several components, including L2 students’ literacy abilities, their prior knowledge regarding the civics topics presented in texts, their disciplinary literacy abilities, and their content-area knowledge, that needs to be considered when studying L2 students’ difficulties with reading and understanding of civics texts. These components collectively influence the comprehension of civics texts. The results of this study suggest that individual components, such as complex vocabulary, dense content, and students’ insufficient prior knowledge, do not independently account for the difficulties the students encounter when reading and understanding civics texts (Rinnemaa, Citation2023b).

2.2. Civics teachers’ understanding of L2 students’ difficulties with civics texts

Previous research has also shed light on another relevant factor in this context, namely teachers’ beliefs and expectations regarding their L2 students’ abilities and potential. Teachers’ beliefs and expectations appear to influence how they prepare for and engage with civics texts in their instruction (Dabach, Citation2014; Jaffee, Citation2016; Rangnes, Citation2019; Wedin & Aho, Citation2022). In her study, Dabach (Citation2014) shows that when civics teachers have lower expectations for L2 students based on the students’ lower language proficiency and non-citizenship status, they simplify the content to enhance comprehension.Footnote3 Dabach (Citation2014) argues that simplifying texts is less beneficial for L2 students’ conceptual learning of civics-specific terms and that the reduced content in texts does not provide substantial information upon which students can build new knowledge (Dabach, Citation2014). Similarly, Jaffee (Citation2016) directs attention to civics teachers’ attitudes toward the prior knowledge that L2 students bring to texts in order to understand them. She argues that the value that civics teachers place on students’ prior knowledge is significant for the students’ successful civics learning, their motivation to read texts, and their engagement in civics issues. Moreover, Jaffee (Citation2016) in her study, like Gibson (Citation2017) and Echevarría, Vogt & Short (Citation2017), emphasizes the importance of civics teachers’ understanding of second-language acquisition as a long and complex learning process upon which acquiring and processing new knowledge in civics rely. Similar results are reported by Dong (Citation2017), O’Brien (Citation2011), Cho and Reich (Citation2008), and Beck and McKeown (Citation1991).

2.3. Civics teachers’ views on obstacles to more effective civics teaching to L2 students

Social studies teachers, including civics teachers, pinpoint additional obstacles that impact the quality of their teaching beyond language and content difficulties with texts. These obstacles are the time limitation, the rich content of civics to be covered, and teachers’ need for more knowledge and useful strategies to better support L2 students in civics classrooms (Brown, Citation2007; Cho & Reich, Citation2008; O’Brien, Citation2011; Zhang, Citation2017). These obstacles could be possible reasons why civics teachers tend to focus more on teaching content and give less attention to addressing the language-related needs of their L2 students when teaching civics. According to Rangnes (Citation2019), many social studies teachers, including civics teachers, may feel that they do not provide sufficient support to their L2 students in improving their literacy abilities within the context of social studies. Rangnes (Citation2019) adds that teachers may also feel that they have difficulty in successfully communicating the content of discipline-specific texts in a language that is understandable to their L2 students. Several researchers propose better teacher training as a concrete support for social studies teachers to adapt their teaching for L2 students (Rangnes, Citation2019; Villegas et al., Citation2018).

2.4. The need for other sets of reading abilities for reading and understanding civics texts

Teachers’ expression of a need for adequate strategies for communicating discipline-specific content in texts and their acknowledgement of L2 students’ struggle with discipline-specific texts may have prompted literacy researchers like Shanahan and Shanahan (Citation2008) and Moje (Citation2008, Citation2015) to explore more effective forms of support with discipline-specific texts. It was suggested that learning to read should incorporate using reading abilities to engage in disciplinary learning. According to Shanahan and Shanahan (Citation2008, Citation2012), to engage in social, semiotic, and cognitive practices, consistent with those used by experts such as scholars, teachers, and textbook authors, more advanced sets of reading abilities need to be developed, called disciplinary literacy abilities. From this perspective on literacy, every school subject is a disciplinary discourse recontextualized for educational purposes (Fang & Coatoam, Citation2013). Inspired by this line of reasoning, Fang and Schleppegrell (Citation2010) suggest that literacy practices, such as reading and writing, would be best learned and taught within each school subject. When it comes to reading and understanding civics texts, this view of literacy is relevant. Reading and understanding civics texts are important activities for L2 students, as they serve to support students’ civics learning and civic engagement. Civic engagement could be defined as L2 students’ awareness of, understanding of, and willingness to be informed about civics issues that are concerns of the society in which they live (Chambliss et al., Citation2007; Adler & Goggin, Citation2005).

2.5. Other literacy activities useful for reading comprehension of civics texts

Another perspective that is relevant concerning the multiple purposes of reading civics texts may be seen in Kulbrandstad’s study (Citation1998). She suggests that reading should be seen as a process that involves negotiating meaning between the text and its reader. For this process to be effective, it is important to engage in process-oriented reading, which includes before, during, and after reading (see also Massey & Heafner, Citation2004). Making connections to students’ prior knowledge is necessary during process-oriented reading (Kulbrandstad, Citation1998). In her study, she shows that other literacy activities such as talking should be integrated into work with civics texts. Talking not only allows students to practice their oral language abilities, but also provides them with opportunities to discuss and gain a deeper understanding of the content of the texts, which interaction with others in civics classrooms makes possible. Similarly, Alscher et al. (Citation2022), in their study on the teaching quality in civic education, discuss the importance of creating an open classroom environment where students use their prior knowledge and explore different perspectives to gain a deeper understanding of civics topics beyond what is provided in textbooks. This approach is expected to not only enhance students’ civics knowledge but also stimulate their political interest (Alscher et al., Citation2022). In a similar vein, Wedin and Aho (Citation2022) argue that social studies classrooms are hybrid spaces, where students’ experiences and the school subject meet. They further argue that one of the challenges in teaching and learning social sciences arises when students’ existing frames of understanding, i.e., their experiences, prior knowledge, and perspectives, may not align with the subject content. To address this challenge, it is crucial to relate the content to the students’ earlier experiences and prior knowledge (Wedin & Aho, Citation2022). Additionally, according to Mirra and Garcia (Citation2020), reading and discussing literary texts that are set in various social and political contexts would be an effective way to learn about civics, alongside the use of traditional civics textbooks, since these literary texts provide insights into civic and political issues, making them valuable tools for civics learning (see also Mirra & Garcia, Citation2020).

Writing activities also appear to support L2 students’ reading comprehension of civics texts. By writing their own texts discussing various civics issues such as what people do in democracy and migration policies, L2 students in Jaffee’s study (Jaffee, Citation2016) received meaningful opportunities to internalize and use newly learned civics terms from texts to express their viewpoints more explicitly. In Gibson’s study (Gibson, Citation2017), writing assignments also offered L2 students opportunities to utilize their other language resources to search for information and incorporate the gathered information into their own written texts. As a result, the students’ texts doubled in length and the content became more precise. According to Beck and McKeown (Citation1991, p. 482), “when teachers have an understanding of the barriers created by many content-area textbook selections, they can facilitate the process through alternative reading activities, extensive writing, and discussions.”

3. The conceptual framework and analytical tool

The previous research presented here indicates that separating language and content when studying difficulties with civics texts is almost impossible. It is apparent that challenges with civics texts are not limited to a single aspect or source. It can also be concluded that L2 students’ level of prior knowledge in relation to topics presented in civics texts plays a significant role in their reading comprehension and learning from the texts. Furthermore, teacher support in students’ learning about the discipline-specific characteristics of texts is highlighted by disciplinary literacy researchers as crucial for students’ learning from disciple-specific texts at school.

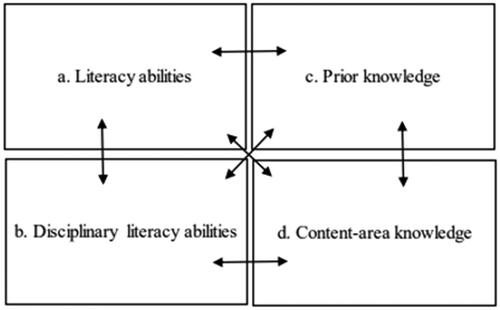

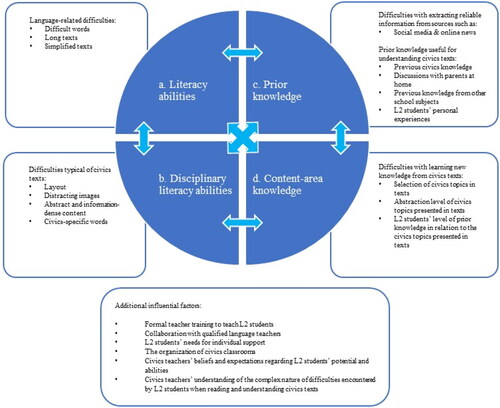

To visualize the complexity of the challenges with civics texts, a four-field model has been constructed by the author (). This model has been used as the conceptual framework and analytical tool in two previous studies (Rinnemaa, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). The model illustrates the interdependence among four components that are argued to be relevant to students’ reading comprehension and learning from discipline-specific texts in civics. These four components are: (a) literacy abilities, (b) disciplinary literacy abilities, (c) prior knowledge, and (d) content-area knowledge.Footnote4 The results from the previous two studies suggest that the interdependence among the four components in the four-field model can be relevant to consider when studying possible sources of difficulties faced by L2 students in relation to civics texts. Moreover, the previous results suggest that there are several additional influential factors, such as teacher support and the organization of civics classrooms, that need to be considered when using the four-field model (Rinnemaa, Citation2023a, Citation2023b).

In this study, the four-field model () is once again used to gain new insights and explore new possibilities that may emerge in civics teachers’ descriptions of their L2 students’ difficulties and opportunities with civics texts. The new insights that may not have been recognized in the previous two studies could contribute to the further development of the four-field model and the validation of its applicability for studying the complexity of difficulties with civics texts.

In this model, literacy abilities refer to sets of reading abilities required to understand, use, and reflect on written texts to develop knowledge and participate actively in society, using the definition of Street (Citation1984) and Gee (Citation2001), modified in Mullis and Martin (Citation2019) and Epstein (Citation2020). Disciplinary literacy abilities, in line with Shanahan and Shanahan (Citation2008) and Moje’s (Citation2015) definition, refer here to reading and interpretation of texts in order to learn, use, and develop civics knowledge. Prior knowledge includes various sources of knowledge that L2 students bring to civics texts to better understand them. These may include L2 students’ language repertoires, prior civics knowledge, and cross-cultural experiences. Content-area knowledge refers particularly to civics knowledge that is to be learned and developed by reading and understanding civics texts.

4. Method

The data in this study were collected within a larger research project in which Swedish second-language students’ opportunities and difficulties with civics texts were studied. The students came from three secondary schools in three different locations within a large city in Sweden. The schools represent low, middle, and high socioeconomic background, based on data retrieved from statistics on parents’ educational background (SALSA, Citation2020–2021). The three civics teachers who have been interviewed in this study are the same teachers whose L2 students in Grade 9 participated in the larger research project (Rinnemaa, Citation2023b).Footnote5 Individual semi-structured interviews with civics teachers were employed. Each interview lasted between 60 and 80 minutes. The teachers were interviewed on one occasion during May–June 2022 at their schools. An interview guide was developed in which eleven main questions, divided into several sub-questions, were constructed to probe the teachers’ responses when talking about their L2 students’ opportunities and difficulties with civics texts (see Appendix Table A1). The questions are organized using the components a-d in the four-field model. The interviews were conducted in a semi-structural way, aiming to invite the teachers to reflect and elaborate further on their experiences and personal views relevant to the study (Brinkmann & Kvale, Citation2015; Holstein & Gubrium, Citation2012). The interview questions were developed through a collaborative process, involving consultation with two colleague researchers who possess expertise in the field. Furthermore, the interview questions underwent a rigorous testing phase, with valuable input provided by a third colleague who has extensive experience of teaching social studies to students of Swedish as a second language in Grade 9. The testing phase focused on assessing the clarity of the interview questions and the time required for the interview. No data from the testing interview are included in the results.

Prior to data collection, the Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved the project (Dnr 2021-03734). Aside from confidentiality, anonymity, and informed consent, the other ethical guidelines considered in this study are reliability, honesty, respect, and accountability (Good Research Practice, Citation2017). All interviews are audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The selected excerpts used in the study are translated from Swedish into English by the author. The teachers’ names are omitted and personal information about them is removed to protect their integrity.

4.1. Participants

The participants are three civics teachers working at three different schools within a large city in Sweden. The teachers are of different ages (48, 36, and 30 years old) and their years in the profession vary (20, 8, and 1.5 years). One of the teachers teaches Swedish as a second language in addition to social studies, while the other two teachers primarily teach social studies, including civics, geography, history, and religious education. All three teachers teach in linguistically diverse classrooms and speak Swedish as their first language.

4.2. Data analysis

A thematic content analysis approach is employed to analyze the data obtained from the interviews (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The thematic content analysis presented in this study is based on predefined themes, specifically the four components outlined in the four-field model (). The four-field model is used exploratively with the purpose of studying whether the sources of difficulties that the civics teachers describe and give examples of could be explained by the interdependence among the four components in the four-field model. One concern in utilizing the four-field model for data analysis is the potential omission of other significant themes that may have been addressed by the interviewees. The model is therefore used to explore whether there are additional influential factors, beyond the model, that the civics teachers address in their responses.

Taking inspiration from Braun and Clarke’s six phases of data analysis (Citation2006, p. 87), a systematic analysis process was followed. The first step involved becoming familiar with the data, which included extensive readings and re-readings of the interview transcripts. In the second step, themes that could be linked to each of the four components in the four-field model were identified and marked with different colors. The third step involved underlining and marking words, examples, and explanations provided by the teachers that could be linked to each theme within the four-field model. The fourth step consisted of further studying the specifics of each theme to assess whether rearrangements would be needed. In the fifth step, themes that did not directly align with the four themes in the four-field model, but were relevant to the results and the research questions, were marked. The sixth step involved selecting and marking extracts and quotations that would enhance the clarity and comprehensibility of the analysis. In the final step, the transcript was reread to make sure that nothing significant had been overlooked. In the following section, a more detailed explanation is provided regarding the methodology used to organize each theme within the teachers’ responses.

The first theme, literacy abilities, was studied by searching for responses in which the civics teachers described the language-related aspects of civics texts that they considered would be relevant to the difficulties perceived by L2 students. For instance, the teachers were asked questions like: When reading and understanding texts in civics, what challenges do you think your L2 students often meet? How would you explain these difficulties? When discussing the language-related difficulties with civics texts, the teachers mentioned, for instance, the high frequency of civics-specific words and the use of long sentences with advanced sentence structures in civics texts as factors that complicate reading and understanding of them. When discussing the language-related difficulties with civics texts, words such as language proficiency, Swedish language, vocabulary, grammar, text structures, and reading abilities were frequently used in the teachers’ responses.

When studying the theme of disciplinary literacy abilities, the focus was on responses in which the civics teachers reflected on characteristics that they considered typical of civics texts and made them difficult to understand for L2 students. The civics teachers were asked questions like: How would you describe a typical text in civics? Can you give examples of some elements in civics texts that make the reading of them more difficult for L2 students? For instance, the civics teachers described texts in civics as “information dense,” with abstract and discipline-specific content. The teachers also mentioned the layout and the use of semiotic resources such as images and tables in civics texts as possible sources of difficulties. The civics teachers often discussed the typical characteristics of civics texts when comparing them to texts in other school subjects. For instance, the teachers noted a difference in how images are perceived in science texts compared to civics texts, particularly in terms of precision and their connection to the text. The teachers also considered texts in science when comparing the layout and the frequency of civics-specific words in civics texts. For instance, the teachers reported that the presence of these words in civics texts can make comprehension more challenging, particularly when there is limited explanation provided for these words. Words such as dense content, civics-specific words, abstraction level, layout, images, figures, and tables emerged in the teachers’ responses when they described certain characteristics of civics texts that make them difficult for L2 students to understand.

The theme of prior knowledge was studied by searching for responses in which the civics teachers reflected on the relationship between the civics topics presented in texts and L2 students’ level of prior knowledge in relation to them. The teachers were asked to give examples of meaningful resources that they considered beneficial for L2 students’ understanding of civics texts. The teachers were asked: Can you give examples of contexts or activities both outside and inside the school that you think would benefit L2 students’ understanding of civics texts? For instance, the civics teachers mentioned students’ life experiences and their previous civics knowledge from earlier school grades as meaningful resources. When searching for this theme, words such as students’ previous knowledge, life experiences, digital tools, internet, newspapers, earlier school grades, everyday knowledge, activities outside school, students’ personal interests, and parental support were mentioned by the civics teachers when they talked about useful resources that would facilitate their L2 students’ reading and understanding of civics texts.

The last theme, content-area knowledge, was studied by looking for responses in which the teachers gave examples of civics topics in texts that would complicate or facilitate L2 students’ reading comprehension of texts. The teachers were asked questions like: Do you observe that certain civics topics within civics texts generate more interest among L2 students compare to others? What do you think is the reason for this? For instance, the teachers stated that L2 students had a better understanding of civics texts when the abstract subjects in the texts were made concrete and connected to real-life situations that the students could easily relate to. Words such as useful knowledge, civic engagement, civics topics, current social issues, interest in creating societal change, political interest, and students’ existing knowledge are mentioned by the teachers in their responses.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that certain words, such as abstraction level, difficult words, and students’ prior knowledge and civics topics were discussed by the teachers across multiple themes, rather than being confined to a single theme (for an overview see ). This, in turn, could be an indication of the complexity of the difficulties associated with civics texts.

4.3. Limitations

A limitation of this study is its small sample size. Given the qualitative nature of the study, the findings are not intended for generalization, as they are specific to a particular context and setting. However, the narratives from civics teachers in this study provide valuable insights into the various sources of difficulties they encounter when working with textbook texts in linguistically diverse civics classrooms. These insights might benefit civics teachers working in similar contexts and schools with linguistically diverse students, while the four-field model provides a framework for identifying and addressing challenges in civics texts.

5. Results

It is noteworthy that textbooks are mentioned by all three civics teachers as the main source of information when teaching civics. The teachers also use other types of texts, including newspaper articles, online documents, and official websites to offer more nuanced perspectives about current civics issues that the students read in textbook texts. It is also notable that in discussions about difficulties with civics texts, the teachers primarily focus on print texts rather than digital textbooks. However, when comparing characteristics like multimodality, layout, and text length, the teachers do comment on texts in digital formats. Teachers A and B note that L2 students find it easier to remember content from print texts compared to reading on digital screens. Teacher C suggests that digital texts can feel fragmented and challenging to comprehend due to the need to scroll through multiple pages.

According to the teachers, the primary aim of reading civics texts is to acquire knowledge about civics issues. Although improving Swedish language abilities and developing reading abilities are not explicitly highlighted as the main goals of reading, the civics teachers recognize them as crucial prerequisites for comprehending and learning from civics texts. Good reading abilities are defined by the teachers as being able to read through texts, identify key information, and develop a holistic understanding of the content.

When presenting the results in the next section, the four components in the four-field model () have been used for organizing the four main themes, consisting of literacy abilities, disciplinary literacy abilities, prior knowledge, and content-area knowledge.

5.1. Literacy abilities

The results from the teachers’ responses in which they specifically reflect on language-related difficulties with civics texts are organized into the following sub-themes: difficult words, long texts, and simplified texts.

5.1.1. Difficult words

All three civics teachers report that a large part of civics lessons is devoted to explaining the meaning of civics-specific words in texts. The teachers explain that they often find it hard to identify which words are difficult for L2 students in civics texts since L2 students may be hesitant to ask for explanations in class due to a fear of appearing less knowledgeable than their peers. Teacher B says:

My L2 students seldom raise their hands and ask if they don’t understand a word. I guess they don’t want to appear as less knowledgeable than their peers. It’s not easy for me to know what words they find difficult in texts. For example, I realized the other day that some of my L2 students had misunderstood the whole message in the text about how clothing industry causes water pollution. They hadn’t understood the meaning of the word pollution [förorening in original] and thought pollution meant to clean something.

Based on the teachers’ responses, it is apparent that all three of them acknowledge that having good knowledge of vocabulary is crucial for understanding civics texts. However, while one teacher claims that L2 students should put less focus on understanding every difficult word in civics texts, the other two teachers report that L2 students should put more effort into looking up difficult words in civics texts. For instance, Teacher A says: “I wish my students would pay less attention to every single word in texts and instead try to understand texts as a whole.” In contrast, Teacher C says: “some students miss out on important words in texts when they skip the words they don’t understand just to get through texts as quickly as possible.”

5.1.2. Long texts

According to Teacher A, the combination of long texts (longer than one page) and abstract civics topics being discussed in the texts is often problematic, in the sense that L2 students easily lose track of the main information in the text. Teacher A adds that the existence of several abstract and civics-specific words in civics texts which cover abstract civics topics like economics, family finances, and globalization often slow down L2 students’ reading speed, disrupt their concentration, and consequently affect their understanding of texts negatively. Teacher B shares this view and argues that the slowed-down reading speed also results in the students having lower motivation for and interest in reading through the whole text.

All three teachers also mention having adequate study techniques as crucial for successful reading comprehension of civics texts. For instance, Teacher A explains, “not all long texts are considered difficult by L2 students if they know how to read them.” Teacher C has a slightly different view and argues that it should not be taken for granted by teachers that all students have already been adequately instructed in reading subject-specific texts in civics.

Teacher C says:

L2 students need to exercise their reading abilities in all school subjects and not only in language courses. I think it’s something that we subject teachers have failed with. I often hear from colleagues that L2 students achieve low grades in several school subjects due to insufficient reading abilities.

5.1.3. Simplified texts

Although civics teachers acknowledge that long texts are difficult for L2 students to comprehend, they do not recommend using simplified texts as an alternative. Civics teachers define simplified texts as summarized or rewritten content with simpler language and fewer civics-specific terms. They highlight disadvantages of using simplified texts, such as incomplete understanding of the main message due to the shortened content and the removal or reduction of linguistic nuances that support the students’ language development. Teacher B suggests that the simplistic language in such texts does not adequately prepare L2 students for advanced reading tasks. However, despite these disadvantages, all three teachers acknowledge using simplified texts due to time constraints. Teacher B says: “using simplified texts is not ideal for L2 students’ learning, but the time limitations don’t allow us to fully work through ordinary texts in class. Simplified texts don’t require much teacher support either.”

5.2. Disciplinary literacy abilities

The following results focus on the teachers’ responses in which they reflect on typical characteristics of civics texts that they consider relevant to the difficulties faced by L2 students. These results are categorized into the following sub-themes: layout, distracting images, abstract and informative content, and civics-specific words. It is worth noting that civics-specific words is a recurring theme here.

5.2.1. Layout

According to civics teachers, the layout of texts, i.e., the appearance of texts, matters for how L2 students experience the level of difficulty in them. For instance, Teacher A describes civics texts as “difficult to read” since they often lack headings, subheadings, introductions, and conclusions. Teacher B provides an example and explains: “when I was working with a text about human rights, I just realized that some of my L2 students read the text in the wrong order, because the text was written in columns as in a newspaper article.” According to Teacher A, “the layout is important to encourage L2 students to become motivated and want to read the whole text.” Similarly, Teacher B explains that students often do not see the main theme in civics texts because the layout in them differs from the layout in texts that students meet in other school subjects such as science. According to Teacher B, in science texts, it is easier to see where a new paragraph starts and ends with help of headings and subheadings. Similarly, Teacher C compares texts in civics with texts in history and says: “without a clear layout, civics texts can easily be viewed by L2 students as a large mass of text they easily get lost in.”

5.2.2. Distracting images

All three teachers mention that images in civics texts can both complicate and support L2 students’ reading comprehension. The teachers explain that the number of images, what they illustrate, and where in texts they are placed has relevance for L2 students’ understanding of civics texts. According to Teacher A, “images can be distracting when they draw attention away from the content of texts to themselves.” According to Teacher B, it is not only images but also diagrams, figures, and tables in civics texts that cause difficulties for L2 students. Teacher B suggests that L2 students may struggle with civics texts because they lack practice in interpreting information from multimodal resources such as tables and diagrams. However, unlike Teachers A and B, Teacher C does not report difficulties caused by images or diagrams in civics texts. This is illustrated in the following quote: “I’ve never thought about how my L2 students react to multimodal resources in civics texts.”

5.2.3. Abstract and information-dense content

Typical civics texts are described by the teachers as abstract texts in which the content is more informative rather than argumentative. According to Teacher A, “civics texts are very information dense, with lots of facts embedded in them.” Teacher B mentions the high abstraction level as a typical element in civics text, causing L2 students to find civics texts less interesting to read. When talking about the abstract content of civics texts, the aspect of time once again recurs in the teachers’ responses. Teacher B explains that due to time constraints and large student groups with various individual needs for teacher support, the reading of civics texts is often limited to “reading what is on the line” and “little time is left for reading what is beyond the lines.”

5.2.4. Civics-specific words

The high number of civics-specific terms is mentioned by all three civics teachers as another typical characteristic of civics texts that makes them difficult to understand. The teachers report that they often feel responsible for explaining the meaning of civics-specific words since they are not always well-explained in texts. Explaining the meaning of difficult words takes a great amount of lesson time, which teachers suggest should be put into more important activities. All three teachers wish that they could create more classroom activities that allow L2 students to use civics-specific words in more meaningful ways rather than focusing on understanding difficult words. Teachers’ suggestions for classroom activities mainly pertain to reading-comprehension exercises and classroom discussions. Writing activities, for instance, are seldom mentioned by the teachers. One explanation for this can be recognized in Teacher A’s response: “writing assignments are very time-consuming and there is no lesson time left for working with them.”

5.3. Prior knowledge

This section presents results on how civics teachers reflect on the role of L2 students’ prior knowledge in the students’ comprehension of civics texts. Teachers were asked to provide examples of resources from which L2 students usually brought information to civics texts to understand them better. Five types of resources emerge in the teachers’ responses, including (1) previous classroom discussions about current civics issues, (2) information retrieved from social media and news online, (3) discussions with parents at home, (4) previous knowledge acquired within other school subjects in earlier school grades, and (5) L2 students’ personal experiences from living in or visiting other countries.

According to Teacher A, “it’s difficult to evaluate the students’ prior knowledge without having dialogues with them about texts they read.” Based on the teachers’ responses, it seems that conversations about the content of texts often occur before the students read texts. It is not clear whether students receive opportunities to talk about the content of texts during and after reading them as well. The main activities after reading texts seem to be limited to answering the reading comprehension questions and looking up the difficult words in texts.

The second resource used by L2 students is, according to the teachers, social media and online news. Teacher B explains that using social media as a resource can be challenging since it is not always easy for teachers to determine the reliability and credibility of the information obtained by resources online. All three teachers underline that students need guidance and teacher support in finding reliable resources online that provide them with accurate information about civics issues. The teachers also state that it is not always easy for them to know whether the students have read the information online or if they have heard it from someone else. The teachers also raise concerns about the students’ vulnerability to propaganda, misinformation, and fake news, and argue that the information circulated online plays a significant role in how young students perceive reality.

Discussions with parents constitute the third resource used by L2 students, according to the teachers. Those L2 students who have opportunities to discuss the content of civics texts at home with their parents show better understanding of texts, the teachers report. Teacher C says:

[…] what prior knowledge L2 students have depends on their situation at home. Those students who have highly educated parents receive more support at home and generally have better grades at school, whereas I have L2 students who have been traveling around before they settled down in Sweden, and then I have students with less educated parents who don’t get much support at home. It’s tough for them.

L2 students’ personal experiences are mentioned as the fifth resource by the teachers. According to Teacher C, understanding civic issues in texts that L2 students can relate to and have personal experiences of is perceived as less difficult by students. L2 students are also more motivated to read about civics topics that they have some preunderstanding of. Teacher B raises another important aspect in this context and argues that L2 students may struggle to recognize the correlation between new civics knowledge in texts and their prior knowledge without teacher support.

Moreover, when reflecting on L2 students’ prior knowledge, none of the teachers explicitly raise L2 students’ first language (L1) as a resource for understanding texts in civics. L1 is instead referred to as an asset for supporting L2 students’ development of the Swedish language. The only time teachers talk about the students’ L1 as a part of their prior knowledge is when they describe the importance of having access to bilingual teacher assistants in civics classrooms. Bilingual teacher assistants are primarily portrayed by civics teachers as useful resources for translating and explaining difficult words for L2 students in their first language.

5.4. Content-area knowledge

The following section presents results from civics teachers’ responses, in which they reflect on and give examples of the civics topics in civics texts that, according to them, complicate the learning of new knowledge for L2 students. All three teachers highlight that their choice of civics topics in texts often aligns with the central content specified in the civics curriculum in Grade 9. According to the teachers, civics texts in Grade 9 generally cover subjects such as human rights, democracy, electoral systems, forms of government, and laws and regulations in Sweden.

The teachers indicate that there seems to be a relationship between the level of difficulty in texts and the civics topics presented in them, and they provide two reasons for this. Firstly, civics texts are experienced as less difficult by L2 students when they find the civics topics presented in them interesting and relevant to their everyday life. Secondly, the interesting civics topics in texts are the subjects that L2 students have some prior knowledge of, and they can therefore easily relate to. One example of this correlation is illustrated in Teacher B’s explanation. According to Teacher B, economics, including family finances, is a civics topic in texts that most L2 students find less interesting since they often struggle with understanding abstract concepts like taxing and inflation. However, once L2 students receive teacher support in making the abstract content of texts on family finances more concrete, and connecting it to real-life situations, they find the same text less difficult to understand. Teacher B says:

I’ve realized that asking specific questions about real-life scenarios, for example, what happens if someone in your household becomes unemployed, can make abstract topics like family finances more concrete for the students. It can be difficult for some students to make such connections on their own […] so I use real-life examples to lay a common foundation before introducing my students to advanced civics concepts.

Moreover, the results indicate that the main purpose of reading civics texts, according to all three teachers, is to provide students with civics knowledge. “Sufficient reading abilities” and “having good knowledge of Swedish language” are acknowledged by all three teachers as crucial prerequisites for students’ understanding of civics texts. However, two teachers explain that due to L2 students’ varying level of reading abilities and language proficiency in the Swedish language, it is difficult to identify the precise sources of difficulties with civics texts. Teacher A says:

[…] what I’m evaluating as a civics teacher is the students’ civics knowledge […] I’m not always sure what reading difficulties L2 students face when reading civics texts. I’d know better if I could listen to students when they read a text to me, and if I could cooperate with a colleague who’s qualified in teaching L2 students, but these things take time to organize.

5.5. Additional influential factors

The three teachers comment on several factors that go beyond the language and content challenges associated with civics texts, which, according to them, are relevant to the extent of their support for L2 students when working with civics texts. Teacher C, like Teacher A, expresses a need for formal training in teaching L2 students, and regular collaborations with qualified language teachers to better support their L2 students with civics texts. Teacher C also pinpoints the organization of civics classrooms as another possible obstacle to providing sufficient support to L2 students and expresses concern about separating L2 students from their L1 peers as a less beneficial way of organizing civics classrooms. According to Teacher C, such groupings create a subtractive schooling environment and lead to L2 students feeling excluded from the teaching. Teacher C’s concern is mirrored in the following quote: “my L2 students sometimes ask me why they can’t be in the same class as their Swedish friends. I really hope our principals put an end to separating students from each other. It’s not optimal for anyone.” An overview of the results is presented in .

6. Discussion

This study sought answers to two research questions. The results for the first research question revealed several sources of difficulties that emerged in the civics teachers’ responses regarding L2 students’ reading and understanding of texts in civics. An interdependence among the four themes, (a) literacy abilities, (b) disciplinary literacy abilities, (c) prior knowledge, and (d) content-area knowledge, can be identified in the teachers’ descriptions of L2 students’ different types of difficulties with civics texts. The results in this study confirm the findings from the two previous studies (Rinnemaa, Citation2023a, Citation2023b) demonstrating the complex nature of L2 students’ difficulties with reading and understanding of civics texts. For instance, the language-related difficulties in texts (e.g., simplified texts and complex civics-specific words) in addition to content-related difficulties (e.g., abstract civics topics) seem to complicate understanding of civics texts for L2 students, according to the teachers. The important role of L2 students’ prior knowledge in understanding of civics texts is repeatedly underlined in the results as well. Based on the results, it is not always L2 students’ insufficient prior knowledge that complicates their understanding of civics texts. The difficulties can also arise when L2 students struggle to connect their prior knowledge with new information encountered in civics texts, especially when support from civics teachers is missing. Also, the important role of civics teachers in concretizing the content of civics texts for supporting L2 students’ reading comprehension is acknowledged (see also Walldén & Nygård Larsson, Citation2022; Wedin & Aho, Citation2022). This is illustrated in the example provided by Teacher B, showing how abstract civics concepts such as tax regulation and family finances could be more easily understood by L2 students when they were supported in relating these concepts to real-life situations.

It is also apparent that when L2 students have encountered the civics topics in texts in non-Swedish contexts, they show more interest and engagement in reading texts covering such subjects. This could be observed in Teacher C’s example where L2 students asked their teacher for more texts about gender equality. Another explanation for L2 students’ increased interest in such civics topics could be that their teacher and peers recognize and value their prior knowledge when discussing these subjects in the civics class. This corresponds well with findings from previous studies focusing on L2 students’ civics learning (Blankvoort et al., Citation2021; Di Stefano & Camicia, Citation2018; Jaffee, Citation2016, Citation2022; Mirra, Citation2018).

The second research question was aimed at exploring civics teachers’ reflections about resources that they considered crucial for supporting L2 students’ reading comprehension of civics texts. Civics teachers highlight five resources that according to them could have relevance for understanding of civics texts and learning from them (). When it comes to using external sources like social media and online news or understanding civics texts at school, the teachers, on one hand, pinpoint the difficulties of evaluating the reliability of the information retrieved from such sources and express concern over the students’ exposure to propaganda and fake news when searching for further information online (see also Gibson, Citation2017). On the other hand, the teachers emphasize the importance for L2 students’ civics knowledge development of employing online sources in which civics issues are discussed from various perspectives. This, in turn, raises the idea that what L2 students read and learn about civics issues outside school should be brought in and discussed in civics classrooms, enabling teachers to support the students in distinguishing reliable information from misinformation.

Moreover, the extent to which civics teachers include L2 students’ prior knowledge in their civics teaching seems to be crucial. Teachers in this study report that they seldom have time left for building on students’ prior knowledge after reading texts. This is problematic since comprehensive understanding of new information in texts requires opportunities for students to connect the new information with what they already know, facilitated through interactions in the civics class (see also Kulbrandstad, Citation1998; Wedin & Aho, Citation2022).

Another aspect worth nothing here is that in the teachers’ responses, L2 students’ first language (L1) is not mentioned as a resource for understanding civics texts but rather as an asset for developing Swedish language abilities. The teachers recognize the benefits of having bilingual teacher assistants, primarily for translating and explaining difficult words in L2 students’ first languages. However, the specific involvement of bilingual teacher assistants in working with civics texts is not explicitly explained by any of the teachers. Due to the significant linguistic diversity among L2 students in Swedish classrooms, organizing bilingual teacher assistants in civics classrooms can be challenging. This could also be a possible reason for the absence of discussions about translanguaging as a useful resource for understanding civics texts in the teachers’ responses.

Furthermore, while the teachers in the study mention “knowing how to read civics texts” as crucial for improving L2 students’ understanding of civics-specific texts, they do not explain specific details of reading instructions in their responses. It can be suggested that civics teachers, being well-equipped with knowledge of the language- and content-related characteristics of civics texts, are the ideal candidates to provide explicit reading instructions in this regard.

Finally, the teachers consistently highlight two recurring themes when reflecting on obstacles to effective language- and content-integrated instruction when working with civics texts: time constraints and the wide range of civics content. They acknowledge spending a significant amount of lesson time explaining complex vocabulary, which they believe may not necessarily enhance L2 students’ civics learning. Instead, the teachers wish L2 students could engage with civics concepts in more meaningful ways, such as through their own language production (e.g., oral and writing assignments). However, a contradiction can be recognized in the teachers’ reasoning here. On one hand, they express concerns about L2 students’ limited understanding of civics concepts beyond memorizing definitions of the difficult words. On the other hand, a considerable part of civics lessons appears to be focused on word explanations and answering comprehension questions about the texts. Moreover, the teachers’ suggestions for additional literacy activities primarily pertain to oral presentations, which, according to them, require less time for preparation and follow-up work compared to writing assignments. This contradiction may suggest a need to create more activities in civics classrooms though which L2 students receive several opportunities to use and develop what they learn from civics texts in meaningful ways. One example is through writing civics assignments. This conclusion is supported by findings from previous research, in which L2 students expressed a need for more writing assignments (e.g., writing debate articles) that offer them meaningful opportunities to reflect and communicate their thoughts on civics issues that they read about in texts (Rinnemaa, Citation2023b).

7. Conclusion

It is apparent that the complex nature of difficulties with civics texts presents challenges for both L2 students and their civics teachers. The teachers express uncertainty about identifying the source of difficulties encountered by L2 students. However, in the teachers’ detailed narratives, an interdependence between the four components a–d in the four-field model () can be identified when they talk about language- and content-related difficulties associated with civics texts. The results imply that utilizing the four-field model to identify specific areas of difficulty and focusing on improving those areas could support civics teachers in facilitating L2 students’ acquisition of better strategies to cope with the challenges posed by civics texts. As a result, L2 students can become more confident and proficient learners in civics. This study also emphasizes the importance of integrating L2 students’ prior knowledge into civics teaching. Civics teachers report that they find it challenging to allocate sufficient lesson time for building on this knowledge after reading texts. This missed opportunity hinders the comprehensive understanding of civics texts, as it is essential to connect new information with the existing knowledge that L2 students bring to the texts. This, in turn, underscores the need to diversify classroom activities, allowing L2 students to apply what they learn from civics texts more meaningfully, including through oral and written assignments. These activities provide opportunities for L2 students to communicate and deepen their thoughts regarding civics issues encountered in texts. Finally, the teachers’ narratives draw attention to factors that go beyond the four-field model, which were not initially included when constructing the model, but which appear to be essential for supporting L2 students in reading and understanding civics texts. For instance, the individual needs of L2 students, the organization of civics classrooms, and the civics teachers’ beliefs and expectations regarding their L2 students’ abilities, are crucial factors in the teachers’ preparation of civics texts and teaching in multilingual instruction settings.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the civics teachers who participated in the study despite the restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The author would also like to thank Dr. Catherine MacHale Gunnarsson for offering suggestions regarding the language. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Literacy development involves four abilities: reading, writing, listening, and talking.

2 Second language (L2) refers to the language that students acquire in addition to their first language(s) either during early childhood or when migrating to a new country. In Sweden, Swedish is the official language in school and society.

Since L2 students in some classroom settings in other parts of the world than Sweden can be homogenous, for instance in Spanish-English bilingual classrooms in the U.S.A. where all L2 students may have Spanish as their common L1, the term linguistically diverse students is used in the title of this paper to emphasize the variety of linguistic backgrounds among L2 students taught by the teachers in this study.

3 Non-citizen status refers to students who had not yet received their citizenship as they were newly arrived in the USA.

4 The indicators a-d in the model do not designate any hierarchical order between the components, and the two-headed arrows illustrate the interplay between them.

5 Grade 9 is selected since it is the final year within the compulsory school system in Sweden where students are expected to have acquired the fundamental knowledge in civics before entering other stages in life.

References

- Adler, R. P., & Goggin, J. (2005). What do we mean by “civic engagement”? Journal of Transformative Education, 3(3), 236–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344605276792

- Alscher, P., Ludewig, U., & McElvany, N. (2022). Civic education, teaching quality and students’ willingness to participate in political and civic life: Political interest and knowledge as mediators. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(10), 1886–1900. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01639-9

- Arensmeier, C. (2018). Different expectations in civic education: A comparison of upper-secondary school textbooks in Sweden. Journal of Social Science Education, 17(2), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.4119/jsse-868

- Beck, I. L., & McKeown, M. G. (1991). Research directions: Social studies texts are hard to understand: Mediating some of the difficulties. Language Arts, 68(6), 482–490. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41961894.

- Blankvoort, N., van Hartingsveldt, M., Laliberte Rudman, D., & Krumeich, A. (2021). Decolonising civic integration: a critical analysis of texts used in Dutch civic integration programmes. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(15), 3511–3530. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1893668

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brinkmann, S., & Kvale, S., (2015). InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications Inc.

- Brown, C. L. (2007). Strategies for making social studies texts more comprehensible for English-language learners. The Social Studies, 98(5), 185–188. https://doi.org/10.3200/TSSS.98.5.185-188

- Chambliss, M., Richardson, W., Torney-Purta, J., & Wilkenfeld, B. (2007). Improving textbooks as a way to foster civic understanding and engagement. CIRCLE Working Paper 54, Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED497604.pdf.

- Cho, S., & Reich, G. A. (2008). New immigrants, new challenges: High school social studies teachers and English language learner instruction. The Social Studies, 99(6), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.3200/TSSS.99.6.235-242

- Dabach, D. (2014). “You can’t vote, right?” When language proficiency is a proxy for citizenship in a civics classroom. Journal of International Social Studies, 4(2), 37–56. https://www.iajiss.org/index.php/iajiss/article/view/149.

- Dabach, D. B. (2015). “My student was apprehended by immigration”: A civics teacher’s breach of silence in a mixed-citizenship classroom. Harvard Educational Review, 85(3), 383–412. https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.85.3.383

- Dabach, D. B., Fones, A., Merchant, N. H., & Adekile, A. (2018). Teachers navigating civic education when students are undocumented: Building case knowledge. Theory & Research in Social Education, 46(3), 331–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2017.1413470

- Deltac, S. M. (2012). Teachers of America’s immigrant students: Citizenship instruction for English language learners [Doctoral dissertation]. Emory University, USA. Emory University Theses and Dissertations Archive. https://etd.library.emory.edu/concern/etds/6q182k28d?locale=en.

- Di Stefano, M., & Camicia, S. P. (2018). Transnational civic education and emergent bilinguals in a dual language setting. Education Sciences, 8(3), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8030128

- Dong, Y. R. (2017). Tapping into English language learners’ (ELLs’) prior knowledge in social studies instruction. The Social Studies, 108(4), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377996.2017.1342161

- Echevarría, J., Vogt, M., & Short, D. (2017). Making content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP Model (Fifth ed.). Pearson Education, Inc.

- Epstein, S. E. (2020). Supporting students to read complex texts on civic issues: The role of scaffolded reading instruction in democratic education. Democracy and Education, 28(2), 1-12. https://democracyeducationjournal.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1475&context=home

- Fang, Z., & Coatoam, S. (2013). Disciplinary literacy: What you want to know about it. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 56(8), 627–632. https://doi.org/10.1002/JAAL.190

- Fang, Z., & Schleppegrell, M. J. (2010). Disciplinary literacies across content areas: Supporting secondary reading through functional language analysis. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53(7), 587–597. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.53.7.6

- Frankel, K. K., Becker, B. L., Rowe, M. W., & Pearson, P. D. (2016). From “what is reading?” To what is literacy? Journal of Education, 196(3), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205741619600303

- Gee, J. P. (2001). Discourse and sociocultural studies in reading. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Methods of literacy research (pp.129–142). Routledge.

- Gibson, M. L. (2017). De los derechos humanos: Reimagining civics in bilingual & bicultural settings. The Social Studies, 108(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377996.2016.1237465

- Good Research Practice. (2017). Swedish Research Council. https://www.vr.se/download/18.5639980c162791bbfe697882/1555334908942/Good-Research-Practice_VR_2017.pdf.

- Jaffee, A. T. (2016). Social studies pedagogy for Latino/a newcomer youth: Towards a theory of culturally and linguistically relevant citizenship education. Theory & Research in Social Education, 44(2), 147–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2016.1171184

- Jaffee, A. T. (2022). “Part of being a citizen is to engage and disagree”: Operationalizing culturally and linguistically relevant citizenship education with late arrival emergent bilingual youth. The Journal of Social Studies Research, 46(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssr.2021.11.003

- Holstein, J. A., & Gubrium, J. F., (2012). Establishing a Balance. In Holstein, J. A., & Gubrium, J. F. (3rd ed.). Varieties of narrative analysis (pp.1-12). Sage Publications Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506335117

- Jiang, L. (2022). Facilitating EFL students’ civic participation through digital multimodal composing. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 35(1), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2021.1942032

- Kulbrandstad, L. I. (1998). Lesing på et andrespråk. En studie av fire innvandrerungdommers lesing av lærebokstekster på norsk [A study on four immigrant students’ reading of textbooks in the Norwegian language] [Doctoral dissertation]. Acta Humaniora 30 Universitetsforlaget, Oslo University, Norway.

- Levine, P. (2007). Collective action, civic engagement, and the knowledge commons. Hess.

- Massey, D. D., & Heafner, T. L. (2004). Promoting reading comprehension in social studies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 48(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.48.1.3

- Mirra, N. (2018). Educating for empathy: Literacy learning and civic engagement. Teachers College Press.

- Mirra, N. (2022). The union of civics and ELA. Council Chronicle, 32(2), 10–11. https://doi.org/10.58680/cc202232194

- Mirra, N., & Garcia, A. (2020). “I hesitate but I do have hope”: Youth speculative civic literacies for troubled times. Harvard Educational Review, 90(2), 295–321. https://doi.org/10.17763/1943-5045-90.2.295

- Moje, E. (2015). Doing and teaching disciplinary literacy with adolescent learners: A social and cultural enterprise. Harvard Educational Review, 85(2), 254–278. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1691427618?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.85.2.254

- Moje, E. B. (2008). Foregrounding the disciplines in secondary literacy teaching and learning: A call for change. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52(2), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.1598/JAAL.52.2.1

- Mullis, I. V., & Martin, M. O. (Eds.). (2019). PIRLS 2021. Assessment frameworks. International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement. TIMSS & PIRLS Lynch School of Education. Boston College. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED606056.pdf

- Myers, J., & Zaman, H. (2009). Negotiating the global and national: Immigrant and dominant-culture adolescents’ vocabularies of citizenship in a transnational world. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 111(11), 2589–2625. Florida State University Digital Library. https://diginole.lib.fsu.edu/islandora/object/fsu:209947/datastream/PDF/view https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810911101102

- Nilsson, J., & Bunar, N. (2016). Educational responses to newly arrived students in Sweden: Understanding the structure and influence of post-migration ecology. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 60(4), 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2015.1024160

- O’Brien, J. (2011). The system is broken and it’s failing these kids: High school social studies Teachers’ attitudes towards training for ELLs. Journal of Social Studies Research, 35(1), 22–38. https://www.proquest.com/docview/866771318?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true.

- Rangnes, H. (2019). Facilitating second-language learners’ access to expository texts: Teachers’ understanding of the challenges involved. L1-Educational Studies in Language and Literature, 19, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.17239/L1ESLL-2019.19.01.16

- Reichenberg, M. (2000). Röst och kausalitet i lärobokstexter. En studie av elevers förståelse av olika textversioner [Voice and causality in textbook texts. A study of students’ understanding of different versions of texts] [Doctoral dissertation]. Gothenburg studies in educational sciences, Gothenburg University.

- Rinnemaa, P. (2023a). Adolescents’ learning of civics in linguistically diverse classrooms: A thematic literature review. The Journal of Social Science Education, 22(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.11576/jsse-4768

- Rinnemaa, P. (2023b). Linguistically diverse students’ perceptions of difficulties with reading and understanding texts in civics. ERL Journal, 2(8), 116–135. https://doi.org/10.36534/erlj.2022.02.11

- SALSA. (2020-2021, 2021-2022). Statistisk modell utgiven av Skolverket [A statistical model published by the Swedish National Agency for Education]. https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/salsa-statistisk-modell.