Abstract

Activation of prior knowledge is vital for reading comprehension. However, little is known about students’ perceptions of what prior knowledge they view as significant for improving their learning from textbook texts in civics. This study explores how Swedish ninth-grade students, aged 14–16, with diverse linguistic and educational backgrounds, engage with two grade-level civics textbook texts by drawing on their prior knowledge. A four-field model is used to closely study the possibilities with civics texts, focusing on students’ prior knowledge. Thematic content analysis of the students’ statements from two think-aloud sessions reveals the emergence of seven distinct categories of prior knowledge. For instance, parents’ narratives and teacher explanations are underlined as essential resources for students to enhance their comprehension of the content of civics texts, thereby supporting their civics learning. The findings suggest that challenges with civics texts may not be a result of a lack of prior knowledge but may rather be due to the limited opportunities the students receive to activate their prior knowledge when engaging with civics texts. The students report that they face challenges in activating their prior knowledge when they encounter language- and content-related difficulties with civics texts. This underscores the pivotal role of civics teachers in facilitating prior knowledge activation before, during, and after reading civics texts. The four-field model can be used as a tool for analyzing and understanding the intricacies of reading civics texts. Using the model could support civics teachers in designing instruction to minimize challenges and improve students’ learning in civics.

1. Introduction

Textbooks in civics are an important source of information for both teachers and students, and they have a significant impact on the success of students’ learning in civics (Dianti & Fatihah, Citation2021). In alignment with the modern understanding of reading as an active and complex process, it can be stated that reading and learning from civics textbooks should not be perceived as a passive endeavor where students merely extract information from the text. Instead, this process should be viewed as dynamic and intricate, with students actively engaging with texts in various ways to comprehend and learn from them. One way for students to engage with social studies texts, including civics texts, is through activating their prior knowledge from various sources concurrently to construct a representation of the messages of the texts (De Oliveira & Obenchain, Citation2017; Dong, Citation2017; O’Brien, Citation2011; Wedin & Aho, Citation2022).

A review of fifty-four studies on prior knowledge and its activation by Hattan et al. (Citation2023) reveals that these terms are often vaguely defined in research. The broad definitions of these terms indicate that a wide variety of types of knowledge may be considered as prior knowledge. These implicit and broad definitions are less beneficial in providing a clear understanding of the specific type of knowledge being studied (Hattan et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, while previous research emphasizes the importance of activating prior knowledge for successful reading outcomes, there are few studies that specifically examine the types of prior knowledge that students activate and find meaningful when reading and learning from civics textbooks (Rinnemaa, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). This becomes particularly significant when considering L2 students who are still in the process of learning the language through which the content of civics texts is communicated to them. In this context, it is essential to explore the role of the prior knowledge that second language (L2) students bring to their reading, not only in their understanding of the content of texts but also in enhancing their civics learning.Footnote1 Understanding which types of prior knowledge are relevant for learning from civics textbooks is vital, especially in situations where external support, such as teacher guidance, may be limited or not consistently available.

Another notable gap in research concerning L2 students’ civics learning lies in the predominant reliance on civics teachers’ viewpoints and classroom observations, while there is a distinct lack of in-depth exploration of L2 students’ own perspectives and experiences (Rinnemaa, Citation2023b). This omission of L2 students’ viewpoints presents a challenge, as it leaves civics teachers to rely on assumptions rather than having a well-founded understanding of types of prior knowledge that L2 students find meaningful for their learning from civics textbooks (see also Jaffee, Citation2016; Rinnemaa, Citation2023c). This knowledge is crucial for developing effective teacher support, which, in turn, can scaffold the activation of L2 students’ prior knowledge and improve the quality of their civics learning. Therefore, addressing this research gap by incorporating the perspectives of L2 students is essential for a more comprehensive understanding of the process of civics learning.

This study thus aims to explore, using two textbook texts in civics, how L2 students connect to civics textbook texts by activating their prior knowledge in order to develop disciplinary understanding. The research question is as follows: What resources do L2 students consider to be significant for developing knowledge in civics through the reading of texts in civics textbooks?

2. Previous research

This literature review concentrates on investigating the influence of students’ prior knowledge on their comprehension of civics textbook texts. It specifically explores factors associated with these texts, which can either support or impede the activation of students’ prior knowledge.

2.1. The importance of prior knowledge activation

According to Hattan and Dinsmore (Citation2019), prior knowledge activation, a central component of reading comprehension, seldom occurs automatically or effortlessly. In their study, they aimed to understand how third- and fifth-grade students’ prior knowledge activation influenced their reading outcomes when reading social studies and science texts. They applied think-aloud (TA) as a method to study two types of prior knowledge activation, purposeful and ancillary. The participants were asked to think aloud as they read text passages that were part of third- and fifth-grade standardized tests. Purposeful prior knowledge activation occurs when students intentionally bring what they already know to texts to understand them, such as their previous personal experience or previously learned facts and concepts, while ancillary knowledge activation is when students indirectly use their prior knowledge without always recognizing the ways in which prior knowledge helps them construct meaning from texts. Hattan and Dinsmore (Citation2019) argue that employing instructional techniques, such as having students verbalize or write down their comprehension of the primary topics in a text, a practice referred to as knowledge mobilization, is essential for stimulating students to intentionally activate their prior knowledge while reading texts. The authors suggest that not all students are able, without support, to automatically activate their prior knowledge to fulfill advanced text requirements, such as making inferences and adopting a critical stance toward the text content. They use the analogy of “learning to crawl before learning to walk” to emphasize that purposefully activating prior knowledge during text reading should be scaffolded, in the same way that crawling is necessary to develop the muscles needed for walking (p. 42).

However, in another study, Hattan and Alexander (Citation2020) express criticisms regarding the use of knowledge mobilization to activate students’ prior knowledge. One of their criticisms is that knowledge mobilization is often done before reading, rather than being integrated throughout the entire reading process. They suggest that readers should actively engage their prior knowledge before, during, and after the reading process to strengthen connections between their existing knowledge and the information encountered in both spoken and written texts. Another criticism concerns the tendency of knowledge mobilization to narrow its focus to specific topics within texts. This approach may discourage students with limited prior knowledge in those particular areas. A third criticism pertains to the focus of knowledge mobilization on similarities between students’ prior knowledge and the content of texts, which may neglect encouraging students to think about potential differences. This approach can pose challenges for students whose existing knowledge differs from what teachers consider relevant (Hattan & Alexander, Citation2020).

In their qualitative study on the comprehension of history textbooks among linguistically diverse elementary-school students (fifth and sixth grades), Hattan and Alexander (Citation2020) compared the benefits of the knowledge mobilization method with a new approach known as relational reasoning, based on relational reasoning theory. Relational reasoning involves recognizing patterns in texts, such as analogies (similarity), anomalies (discrepancy), antinomies (exclusivity), and antitheses (opposition). These patterns in texts are considered relevant for helping students connect the content of the text with their own knowledge and experiences. For instance, students were encouraged to find similarities (analogies) between their experiences and the text, identify differences or conflicts (anomalies or antitheses), and recognize situations or ideas that are categorically distinct from what they know (antinomies). The results indicated that these relational patterns were particularly beneficial for students in fifth and sixth grades. This is because, at these grade levels, students are expected to identify important parts within a text, make connections across texts, and relate textual content to their own life experiences and prior knowledge (Hattan & Alexander, Citation2020).

Similarly, Alexander (Citation2005) underlines the significance of supporting students in activating their prior knowledge when engaging with texts that demand deeper processing. According to her, some students may find it challenging to access their accumulated knowledge without teacher guidance. The lack of support may result in students missing opportunities to enhance their abilities in comprehending complex texts, potentially leading to a reduced interest in reading. This, in turn, may limit the students’ abilities to “fulfill their responsibilities in a democratic society that relies on an informed and engaged populace.” (Alexander, Citation2005, p. 432). Alexander’s concept of accumulated knowledge stems from her lifespan developmental perspective on reading, emphasizing its progression through various stages. In this view, students’ language and domain knowledge, such as their ability to grasp main ideas, identify key details, and establish meaningful connections, are considered fundamental elements in the development of reading competence. This competence becomes increasingly significant as children mature, and face changes in the purpose and nature of written texts in higher school grades (see also Shanahan & Shanahan, Citation2022 and Duke et al., Citation2021). This shift necessitates the active application of prior knowledge, which encompasses both domain knowledge and topic knowledge (Alexander, Citation2005). However, one aspect that may appear to be missing in Alexander’s lifelong learning perspective is the inclusion of students’ own experiences and knowledge from living in and/or visiting other countries. These experiences and knowledge, often referred to as personal knowledge (McCarthy & McNamara, Citation2021) or funds of knowledge (Moll et al., Citation1992) are emphasized as integral components of students’ prior knowledge, which can significantly contribute to their understanding of complex texts.

2.2. Textual influences on activating prior knowledge in the reading process

Continuing from the earlier discussion on the significance of activating prior knowledge when tackling complex texts, it is essential to explore the potential factors that either facilitate or hinder students in this activation process while reading. These factors are presented next.

2.2.1. Students’ interests and self-defined goals when reading texts

According to Rosenblatt (Citation1995), reading is not a static occurrence solely determined by the text. From Rosenblatt’s perspective, readers bring their “intellectual baggage,” which includes assumptions, personality traits, memories of earlier events, life experiences, present preoccupations, and cultural backgrounds, to the texts they read in order to make meaning from them. One of Rosenblatt’s major contributions to the field of reading is her emphasis on the active role of readers in constructing meaning by utilizing their prior knowledge and life experiences. Although Rosenblatt’s research primarily focuses on the reading of literary texts, the fundamental concept of considering the interaction between the reader and the text is applicable and valuable when understanding the reading process for other types of texts, for example expository or informational texts, such as civics textbooks.Footnote2

Fox and Parkinson (Citation2017) highlight two important factors for successfully activating prior knowledge when learning from textbook texts: students’ personal interest in the topics presented in texts and their use of effective study techniques. Personal interest can stem from students’ individual underlying needs or desires, deeply connecting students to the topics in texts. It can also be situational, arising temporarily in response to specific topics within the context of a text (Hidi, Citation1990). Additionally, Kintsch (Citation2005) emphasizes that the reader’s self-defined goals and purposes of reading play a significant role in motivating the reader’s efforts to connect information within a text to his/her existing knowledge, thereby making meaning from the text. Similarly, Duke et al. (Citation2021) emphasize that the comprehension process of reading varies based on what and why one is reading. This implies that the type of texts and the purpose of reading can significantly impact comprehension. They further argue that the purpose of reading “is shaped by many facets of the context in which one is reading” (p. 666). For instance, the purpose of reading differs in relation to whether one reads a text as a school assignment or for pleasure. Within this context, Duke et al. (Citation2021) underline the importance of creating instructional practices that encourage reading motivation among readers, simply because more interesting texts require less effort to understand. Duke et al. (Citation2021) further suggest various ways to support students in engaging with texts they read at school, including increasing students’ reading volume outside of school and creating writing activities that enhance reading comprehension beyond simple question-answer activities when working with school texts.

The significance of students’ individual purposes and interests in understanding texts is also illustrated in Tatum’s study (Tatum, Citation2022), focusing on literary texts and involving 3,126 middle- and high-school students from diverse backgrounds. Tatum found that students were more likely to remember and connect with classic literature featuring characters of their own age. This suggests that personal significance enhances students’ engagement with books, allowing them to relate to and gain insights into their peers’ experiences and influencing their own perspectives and emotions. Similarly, Mirra and Garcia (Citation2020) emphasize literary texts as a significant source of civics learning beyond traditional textbooks. They argue that reading and discussing these texts, which depict various social and political issues, allows students to connect these issues to their own reality. Moreover, (Lindholm & Lyngfelt, Citation2015) suggest that engaging in discussions about texts, rather than solely relying on written responses to texts is recommended, since discussions provide a more comprehensive understanding of what L2 students have learned from literary texts.

The potential of literary texts in activating students’ prior knowledge, and facilitating their nuanced understanding of these texts, raises the question of what characteristics in civics textbooks would either facilitate or hinder the activation of students’ prior knowledge during the process of reading. Next, some key characteristics of social studies textbook texts, including civics textbooks, are presented.

2.2.2. Structure and coherence in social studies texts, including civics texts

Beck and McKeown (Citation1991) point out two factors that complicate students’ ability to activate their prior knowledge in relation to social studies texts, including civics texts: the lack of clear structure and the lack of text coherence (e.g., Brown, Citation2007; Cho & Reich, Citation2008; Monte-Sano & De La Paz, Citation2012; Olvegård, Citation2014; VanSledright, Citation2002; Wineburg, Citation1991). Coherence refers to how well the sequencing of ideas in a text makes sense and how the language conveys the nature of ideas and their relationships. Textbooks with simplified content and insufficient explanations to connect ideas make it harder for students to activate their prior knowledge (Clinton et al., Citation2020; see also Brown, Citation2007). Similar findings are presented in a study by Rinnemaa (Citation2023b). In this study, L2 students report that text incoherence in civics texts obliged them to put considerable effort into identifying parts of texts that could be linked together to gain an overall understanding of the texts. This increased effort left students with fewer opportunities to connect what they already knew with new information in the texts, possibly hindering comprehension. According to L2 students, the main goal of reading was to grasp the text structure and understand difficult words, rather than learning from the text. Additionally, the findings revealed a notable preference among L2 students for longer texts, which they found better facilitated their reading comprehension by allowing them to search for clues and explanations in different parts of the text (Rinnemaa, Citation2023b).

Regarding the structures in social studies texts, Beck and McKeown (Citation1991) suggest that the lack of clear structures in social studies texts could make it difficult for students to organize and connect information coherently due to the lack of a predictable structure. This, coupled with students’ insufficient prior knowledge could make comprehending the material difficult for them (Beck & McKeown, Citation1991).

Furthermore, it is important to note that a linguistics-oriented approach, with a particular focus on form, language, and structure in civics texts, is recognized in studies focusing specifically on civics textbooks (e.g., Chambliss et al., Citation2007; Epstein, Citation2020; Kulbrandstad, Citation1998; Rangnes, Citation2019; Reichenberg, Citation2000; Walldén & Nygård Larsson, Citation2022). From this perspective, civics texts are analyzed for difficult words, sentence structures, and cohesion, providing detailed insights into how language elements contribute to students’ understanding of the content. Another perspective, applied by researchers to study the challenges with civics texts, focuses on how the content of civics texts can impact L2 students’ sense of belonging and inclusion or reinforce feelings of power inequalities and cultural differences among students as readers (e.g., Blankvoort et al., Citation2021; Dabach, Citation2015; Dabach et al., Citation2018; Deltac, Citation2012; Di Stefano & Camicia, Citation2018; Gibson, Citation2017; Jaffee, Citation2016, Citation2022). However, separating linguistics-oriented and content-oriented aspects in analyzing civics text readability is challenging, given their interconnected nature.

2.3. Activating prior knowledge: the role of L2 students’ language repertoires

Research indicates that when L2 students engage with civics texts in their second language, incorporating additional text sources in their first language (L1) plays a critical role in enhancing knowledge development. In Gibson’s (Citation2017) case study, middle-school L2 students were encouraged to draw on their experiences in both Mexican and American communities to explore differences between these communities. Classroom activities involved using news coverage, political documents, and social networks in both languages, Spanish (L1) and English, to help the students understand concepts such as fairness, justice, and human dignity. The importance of utilizing L2 students’ L1 for their prior knowledge activation when encountering relevant civics text sources other than textbooks at school is also emphasized by Jaffee (Citation2016, Citation2022), Deltac (Citation2012), and Dabach (Citation2015).

However, one aspect that remains unclear in the studies referred to here pertains to how civics teachers address differences in students’ proficiency levels in their first language(s) when working with civics texts. This raises questions about the resources and support available to civics teachers, enabling them to assist their L2 students in developing their L1 alongside their civics learning. Given that L2 students are diverse groups of learners with varying language proficiencies, and the organizational dynamics of classrooms can differ across educational settings, it becomes imperative to gather in-depth insights into how L2 students could be supported in developing their L1. For instance, in Deltac’s study (2012), which involved interviews with high-school civics teachers, it was reported that these teachers are often aware of varying levels of L1 language proficiency among their L2 students. However, due to time constraints and the extensive content they need to cover, they are often limited to providing only basic language support, such as word explanations. Similar results were reported by Jaffee (Citation2016), who criticized the lack of systematic assessments of L2 students’ language proficiency in both their L1 and L2, as well as of their level of prior knowledge. This absence of systematic assessment leaves civics teachers making imprecise assumptions about their L2 students’ knowledge levels. Relying on informal perceptions of L2 students’ prior knowledge, including their language proficiency in both their L1 and L2, can result in adjustments that, rather than facilitating L2 students’ civics learning and language development, may complicate the process. This can manifest as either oversimplifying the content or setting overly high expectations for students (Dabach, Citation2015; Jaffee, Citation2016).

Another crucial aspect that deserves more attention in this context is the role of parental support as a fundamental component of the definition of funds of knowledge. Jaffee (Citation2016) contributes to this understanding by constructing a theoretical framework for culturally and linguistically relevant civic education (CLRCE) that highlights the notion of funds of knowledge. In Jaffee’s definition (Citation2016), a fund of knowledge encompasses previous experiences of civic education in the social, emotional, and political contexts that L2 students encounter. This definition also incorporates aspects such as commitment to L2 students’ own community, cultural groups, and parental influences. Parental influences are exemplified as the narratives parents share with their children when discussing civics topics at home. These narratives may include family histories, cultural traditions, personal experiences, and moral lessons through which parents convey their values, beliefs, and cultural heritage (Jaffee, Citation2016).

Additionally, it is important to note that while research has extensively explored the role of parental support in the language development of L2 students within the context of family literacy (e.g., Barton, Citation2017; Cairney, Citation2003; Duek, Citation2017; Rodríguez-Brown, Citation2011), there is a significant gap in the understanding of how parents can facilitate their children’s comprehension of civics textbook content by activating prior knowledge. As parents play a dual role in maintaining their children’s first language(s) and supporting the development of a second language in content areas, it is crucial to conduct further research in this area.

3. Theoretical framework

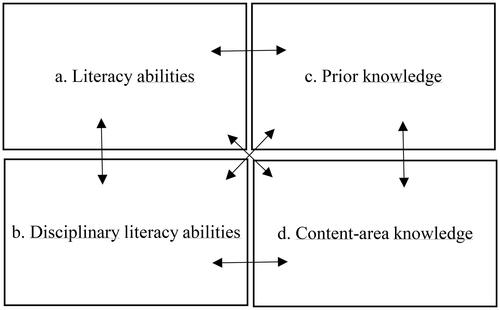

The synthesis of previous research highlights the diverse sets of abilities and knowledge domains required by L2 students when engaging with civics texts. These requisites have been classified by Author 1 into four essential components: (a) literacy abilities, (b) disciplinary literacy abilities, (c) prior knowledge, and (d) content-area knowledge, illustrated in a four-field model (). In this model, literacy abilities encompass fundamental and intermediate reading abilities, building on the definition of Street (Citation1984) and Gee (Citation2001), modified in Mullis and Martin (Citation2019), and Epstein (Citation2020). Taking inspiration from the work of these researchers, literacy, with particular focus on reading abilities, is viewed here as an active process framed within socially situated practices, indicating that literacy is not merely a passive ability but an engaged and context-dependent activity. This study, which focuses on the role of the reader’s prior knowledge in his/her interaction with the text, is influenced by the work of Rosenblatt (Citation1995, Citation2005), and Duke et al. (Citation2021). In particular, compreaction (combining comprehension and action), a term coined by Duke (Citation2020, p. 32), is here emphasized in the context of civics texts, meaning that reading is viewed as an active process in which L2 students make meaning of the content in civics texts that they find interesting and relevant. This line of reasoning could be seen to correspond to Epstein’s (Citation2020) view of literacy. According to Epstein (Citation2020), students as participants in a democracy do not only need to read but also to interpret and evaluate extensive information related to civics issues they read in textbooks and online texts. Disciplinary literacy abilities, aligned with definitions by Shanahan and Shanahan (Citation2008) and Moje (Citation2015), encompass the abilities of reading and interpreting textbook texts in civics. These abilities are critical for acquiring, constructing, and evaluating civics knowledge derived from reading and comprehending civics texts. Prior knowledge involves the diverse sources of knowledge that L2 students bring to civics texts to enhance their understanding. Content-area knowledge specifically refers to the civics knowledge acquired through reading and understanding civics texts. Previous research has separately explored each component or combinations of two components (e.g., literacy abilities and prior knowledge). However, there is a noteworthy lack of exploration of the interplay among the four components (a–d) and the role this interplay might have in supporting L2 students’ reading comprehension and civics learning. Previous studies conducted by Rinnemaa (Citation2023a, Citation2023b) have explored the significance of using the four-field model for investigating potential challenges in reading and understanding civics texts. The findings suggest that an interdependence between the four components a-d needs to be considered when studying the complex nature of difficulties faced by L2 students when reading and understanding civics texts. The interdependence between components a-d is illustrated by the two-headed arrows in the four-field model, and the indicators a-d do not demonstrate any hierarchical order between them.

The findings also indicate that L2 students identify two components from the model () as most significant for their comprehension of civics texts: literacy abilities and prior knowledge (Rinnemaa, Citation2023b). However, many students express hesitation about separating these two components, as they consider their language proficiency in L2 (Swedish) and previous civics knowledge from earlier grades as integral parts of their prior knowledge, contributing significantly to their understanding of civics texts. Another finding (Rinnemaa, Citation2023b) is that most L2 students report that actively drawing on their prior knowledge and using it to build new civics knowledge, acquired from reading civics texts, helps mitigate language- and content-related challenges, making them less of a hindrance to reading comprehension. Building on these findings, the present study specifically focuses on component c, prior knowledge, with the aim of closely examining the types of prior knowledge that L2 students perceive as beneficial for their reading and learning from civics texts. It is challenging to define prior knowledge, as it is a broad term that encompasses many types of knowledge, including the student’s world, textual, and personal knowledge (Hattan et al., Citation2023; Hattan & Alexander, Citation2020). In civics classrooms, where content knowledge is conveyed through diverse resources, including textbooks, students need to activate their prior knowledge to acquire relevant information and discard irrelevant details from texts. This study explores L2 students’ perceptions of significant types of prior knowledge for learning civics from textbooks. Understanding how L2 students view and activate different types of prior knowledge could enable teachers to create opportunities in civics for students to purposefully incorporate their existing knowledge and maximize their learning.

4. Method and study design

This study involves exploring the perceptions of L2 students in Grade 9 through think-aloud (TA) sessions with one student at a time on two different occasions in the fall of 2021, with intervals of two to three weeks between occasions. In total, thirty-six TA with eighteen L2 students in Grade 9 were conducted. Two different civics texts (Text 1 and Text 2), taken from two textbooks suitable for teaching civics in Grade 9, have been used as the tasks. Three researcher colleagues with long-term expertise in the field were consulted when choosing the two civics texts.

TA is a method that allows students to express their thoughts verbally while performing a task. However, relying solely on TA transcripts (verbal reports) for data gathering may not be sufficient (Ericsson & Simon, Citation1993; Charters, Citation2003). Therefore, it is beneficial to complement TA with other activities to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the verbal reports. In this way, TA has the potential to generate valuable insights, and integrating these insights into a broader context through additional activities can further amplify their significance (Charters, Citation2003; Ericsson & Simon, Citation1993; Pressley & Afflerbach, Citation2012). The selection of TA tasks and the instructions provided by researchers during TA are also important factors to consider. For instance, Gibson (Citation1997) underlines that the guidance given to participants in TA should not be directive, nor should it steer them toward a particular approach or mindset, allowing for a more open and unbiased exploration of the outcomes. Gibson (Citation1997) also suggests using a pre-task exercise that would briefly explain the purpose of the task and reduce the “cold start effect” when using TA (p. 58). This approach is also recommended by other researchers to enhance the effectiveness of TA by reducing anxiety and promoting open communication, since verbal reporting tasks, such as reading texts and thinking aloud, are unfamiliar to most readers, particularly young readers (Afflerbach & Johnston, Citation1984).

In this study, each TA took approximately 60 minutes and was conducted in three consecutive steps where the participants (a) read and think aloud about the text, (b) summarize the text orally, and (c) answer the interview questions. The interview guide consists of fourteen main questions, divided into four categories, using the components a-d from the four-field model. Each main question is divided into sub-questions under each category (Appendix)Footnote3. Semi-structured interviews allowed for considerable freedom in the sequencing of questions and in the amount of time and attention given to each theme. Each TA was audio recorded. The interviews were conducted in Swedish by Author 1, in a quiet room at the students’ own schools. The students’ statements from all three steps (a–c) were transcribed, resulting in 575 pages of transcripts. The selected excerpts used in the study are translated from Swedish into English by Author 1. Before conducting the TA, the students gave their written and oral consent, the purpose of the study was explained to them, and one short civics text was used as a training task. This was done with the aim of creating a comfortable environment, helping students feel at ease, and mitigating any potential feelings of being tested.

4.1. Participants

The participants were eighteen L2 students, nine girls and nine boys, aged 14–16 in Grade 9. The students came from three different schools located in two municipalities within a large city in Sweden. The three schools represent low, middle, and high socioeconomic status with regard to the parents’ educational background, according to statistics provided by the Swedish National Agency for Education (SALSA, Citation2020–2021, 2021–2022). The L2 students spoke different first languages, including Albanian, Arabic, Dari, Persian, Spanish, Portuguese, Somali, Tagalog, and Thai. Eleven of the participants were born in Sweden and acquired Swedish as their L2 during early childhood, whereas seven participants acquired Swedish as their L2 after immigrating to Sweden. The duration of the residency time in Sweden varied between two and ten years. Civics teachers in Grade 9 from each school, who had given their consent, were asked to select students, from among those who volunteered, who represented low, middle, and high grades in civics in Grade 9. The researcher deliberately chose not to be informed about the participants’ grades. Participation was voluntary, and included the right to withdraw consent to participate at any time. The names of the students given here are pseudonyms and personal details have been changed to prevent identification.Footnote4 Prior to data collection, the Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved the project (Dnr 2021-03734).

4.2. The texts

The texts read by the students are found in textbooks used in civics education for secondary school in Sweden: “Rights and the judicial system” (Text 1) and “Decision-making and political ideas” (Text 2). Each text is one page in length and they are both included in the textbook Utkik [Lookout] but are from different editions: Text 1 was published in 2014 and Text 2 in 2020.Footnote5

Both texts aim at explaining the political system, based on principles of democracy, in Sweden. Visually they differ from each other. Text 1, from 2014, is organized into three sections, each with a heading in bold: “Who decides?,” “What issues are decided together?” and “What do political decisions have to do with us?” The text below these headings consists of main clauses, with conjunctions underpinning the reasoning of the text. In addition, at the end of the text, there are three images showing two children, a 50 kronor note, and food (a piece of salmon), which take up a quarter of the space of the text. The caption below these images encourages reflection about the meaning of elections and emphasizes that general elections should not be taken for granted. In the running text, key concepts are marked in bold: democracy, constitution, monarchy, governance, representatives, and legal rights. Other words like involves, cherish, insult, and reduction are also used in the text.

Text 2, from 2020, is dominated by a photo of a place outdoors where a variety of political parties present themselves. The text resembles a collage: the photo takes up a quarter of the page, and in addition to this, there are two blue-colored boxes, titled “Electoral participation” and “Church election,” and one box framed in blue with a question about possible reasons for taking part, or not taking part, in public elections. In the running text, there are two lists of bullet points, with information about elections in Sweden and voter turnouts. Linguistically, the text consists of several main clauses with few conjunctions. It is centered on six key concepts: citizens, general election, European parliament, electorate, universal suffrage, and general suffrage, and presupposes knowledge about the meaning of these concepts. Knowledge is also demanded from the reader about the meaning of civics-specific words like city council, regional council, turnout, commissioner, and resident, and everyday words like majority, minority, low-income earners, disability, participation, and variety.

To sum up, the two texts differ from each other by demanding different interpretative skills from their readers. Text 1 relies on verbal reasoning, while Text 2 involves multimodal interpretation and inference-making as well. However, these differences do not make either of the texts unsuitable for this study. Since the aim of the study is to be able to understand what resources L2 students consider to be significant in developing knowledge in civics by reading textbooks, the variation between (and within) these texts could be regarded to be an asset (cf. Lindholm & Lyngfelt, Citation2015). Also, the differences between the texts could be considered to create possibilities for students to connect to the texts, by making use of their different prior knowledge.

4.3. Data analysis

Thematic content analysis is applied, following a six-step process, including familiarization, coding, generating themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and writing up (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). However, when analyzing the data, the preconceived theme of prior knowledge was in focus. In the first step, each individual transcript was read and reread several times to identify all parts in which each L2 student reflected on and gave examples of various sources of knowledge that according to them facilitated their reading of Text 1 and Text 2. This step was necessary but time-consuming, since thirty-six transcripts based on the three phases of the TA needed to be scrutinized (verbal reports, oral summaries of the two civics texts, and the students’ statements from the two interviews). In Step 2, all words, phrases, explanations, and examples that could be linked to different types of prior knowledge and that the students perceived as helpful for understanding the two texts were identified and marked with different colors. The third step involved categorizing various types of prior knowledge that emerged in the data, using the color codes. In the fourth step, various categories of prior knowledge were assembled into a collage to enhance transparency and gain a better overview. In the fifth step, extracts and quotations were selected to improve the clarity of each category. In the final step, the categories were reread to assess whether rearrangements or refinements would be needed and to ensure that nothing of significance had been overlooked.

5. Results

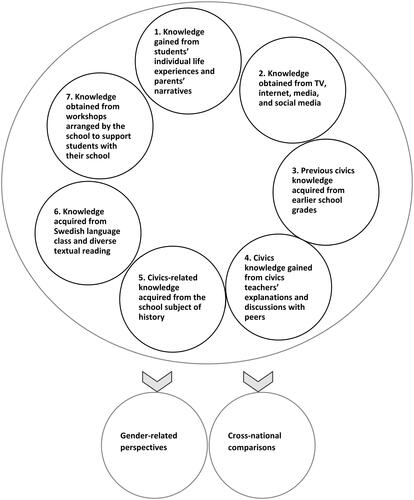

In the analysis of the students’ statements, it becomes evident that there seems to exist a relationship between the topics in the texts and the prior knowledge that L2 students activate and bring to the texts to better understand them. In addition to the topics in the texts, images and parts of the text explaining certain content also seem to support students to draw on their prior knowledge when elaborating on the content of the two texts. For instance, in Text 1, specific topics, such as democracy, freedom of speech, human rights, censorship, freedom of choice, and family finances, and one of the images in particular, that of young children smiling, sparked the student’ interest. This interest led to in-depth discussions about the text, in which the students used their prior knowledge to elaborate further on these topics. In Text 2, topics such as free elections, civic engagement, political decisions, and democratic rights seem to have captured the students’ attention when they discussed the text. The analysis of the results indicate that seven types of prior knowledge emerge when L2 students describe and give examples of the resources that they draw on to enhance their comprehension of Texts 1 and 2. These seven types of prior knowledge are categorized as follows: (1) Knowledge gained from students’ individual life experiences and parents’ narratives, (2) Knowledge obtained from TV, internet, media, and social media, (3) Previous civics knowledge acquired from earlier school grades, (4) Civics knowledge gained from civics teachers’ explanations and classroom discussions with peers, (5) Civics-related knowledge acquired from the school subject of history, (6) Knowledge acquired from Swedish language class and diverse textual reading, Footnote6 and (7) Knowledge obtained from participating in workshops arranged by the school to support students with their school assignments.

The arrangement of these categories (1–7) is based on the frequency of statements from the students during the three phases of TA when discussing various sources of knowledge they bring to Texts 1 and 2 to better understand them, where sources of knowledge that students talked about most frequently were placed in Category 1. The seven categories are presented next (5.1–5.7).

5.1. Knowledge gained from students’ individual life experiences and parents’ narratives

Fifteen of the eighteen students in the study attribute positive effects to parental support in understanding civic topics from Texts 1 and 2. These students outline three main ways through which parental support facilitates their learning: better understanding of civics topics and difficult words in the texts, being engaged with current civic issues like the Swedish election, and receiving support in completing civics-related school assignments, resulting in more satisfactory school results. Additionally, the students highlight that their understanding of their parents’ challenging circumstances before moving to Sweden is greatly enriched by hearing their parents’ personal life stories, providing a depth of insight beyond what can be understood from reading civics texts alone. For instance, Adam says: “Listening to my mom’s stories about her difficult life helps me understand why she moved to Sweden to provide me a better life.” Furthermore, the students in particular refer to the topics democracy, human rights, and free elections from Texts 1 and 2, and acknowledge that their parents’ narratives have played a significant role in deepening their understanding of how political decisions in other countries impact the lives of citizens. For instance, Camilla says: “My mom and I are both very interested in feminism and democratic rights. My mom is active on Facebook, and she sometimes asks me to read the posts with her and we discuss what people write there.” Camilla adds: “My mom always tells me that democracy is about respecting other people’s opinions, even when they don’t agree with you.” Similarly, Julia appreciates her mother’s support and says: “When I struggle with a difficult text in civics, I first summarize it on my own, and then I ask my mom to check if I’ve got it right.” Jesper, another participant, reports that discussions about the election procedures in Sweden with his father made him realize that elections looked completely different in his father’s country of origin. Jesper says: “My dad told me that people in his country don’t have many parties to choose from. There’s only one party and one guy who represents it. I mean, you can’t call it a democracy, can you?” Mikaela explains that discussions with her mother about different parties’ politics offer her better insights into the interests of different parties, and adds: “Sometimes, I realize that what I write in a school assignment is actually the information I’ve learned from my mom during our discussions at home.”

However, it is important to note that not all L2 students in this study report having access to parental support at home. Some students, primarily due to their parents’ limited proficiency in Swedish, lack this support, leading to feelings of frustration and difficulty in achieving satisfactory school results. In contrast, ineffective parental support is also reported by one student who experiences his parents’ support as less effective due to his parents’ use of advanced level of their L1 when explaining abstract civics specific words in civics texts, making it difficult for him to understand.

Regarding language proficiency in L1, the findings reveal another significant aspect. The students indicate that the proficiency of their parents in their L1 significantly influences the narratives shared at home, delving into political and social topics beyond merely explaining difficult vocabulary. It is, however, noteworthy that based on the students’ statements, they do not consider their knowledge of L1 as an asset when engaging with texts at school, including civics texts. According to sixteen out of eighteen students, they seldom use their L1 actively while working with civics texts in the classroom, reserving it as the primary language for use at home. For instance, Benjamin says: “I used to translate everything to my L1 first to understand, but there’s no point in that anymore. I use Swedish for almost everything at school.” Julia says: “No-one else in my classroom speaks my L1 so what’s the point? My classmates won’t understand me anyway.” Similarly, Daniel says that he uses his L1 only at home when he does his homework and refers to Swedish as “the language of school,” while his L1 is referred to as “the language of home.”

5.2. Knowledge obtained from TV, internet, media, and social media

The students report that they regularly use TV, internet, and social media (Instagram and Facebook are frequently mentioned by the students) as supplementary resources along with their school textbooks, including civics textbooks. However, they find it challenging to explicitly determine what specific knowledge or insights gained from these sources contribute to their comprehension of Texts 1 and 2. Their motivation for employing these sources seems to be primarily their curiosity about current social issues like juvenile delinquency and crime in society, which they feel are underrepresented in civics textbooks. However, the students remark that reading online texts does not always lead to a more nuanced understanding of the topics covered in civics textbooks, and they raise concerns about the reliability of online sources. For instance, Tim says: “I don’t trust Wikipedia since I’ve learned that anyone can change the facts there. It’s same with the social media; there’s no guarantee that people writing there don’t spread lies.” Jens, like Tim, says that he does not trust news on the internet and the information written by “ordinary people” on social media. He says: “I only trust what I read in books and hear from my teacher. In books, there’s always an author and the information written there doesn’t suddenly disappear as it does on the internet.”

5.3. Previous civics knowledge acquired from earlier school grades

The students attribute their ability to recognize and activate their prior knowledge of topics such as democracy, family finances, and human rights in Texts 1 and 2 to three main factors in relation to earlier school grades within civics: the development of effective study techniques, exposure to a balanced amount of civics topics, and the peer discussions and explanations provided by civics teachers. Grades 5 through 8 are frequently mentioned by the students. They explain that their ability to recognize the main topics in Texts 1 and 2 from earlier grades depends to a great extent on their use of an effective study technique, which, according to them, involves taking notes and writing down one’s own explanations and summaries while studying civics texts. For instance, Camilla says: “I usually look at my notes from earlier grades when working with new civics concepts. This is much better than searching on Google where you need to go through one thousand pages to find a clear explanation.” Jens says: “I remember better when I look at my notes from earlier grades. I also realize that my Swedish has become better since then.” Similarly, Sara says: “I remember some parts in Text 1 about democracy from Grade 8.”

The second reason given by the students that drawing on their civics knowledge from previous school years gives them a better understanding of Texts 1 and 2 is the balanced exposure to new civics topics. For instance, Jens says: “Texts in Grade 7 were much easier; we learned about one topic at a time, first family finances and then economics. This made it easier to remember what we’ve learned.” Similarly, Jesper explains: “In Grade 7, we read about similar topics [to Text 1], but it’s only now in Grade 9 that I understand what they are about.” The third reason given by students for remembering civics knowledge from earlier school grades and bringing to Texts 1 and 2 is the guidance facilitated by civics teachers and peer discussions. This category is presented next.

5.4. Civics knowledge gained from civics teachers’ explanations and classroom discussions with peers

According to Samuel, one reason that he understood the topics of democracy and types of governance in Text 1 is the classroom discussions with peers and his civics teachers’ explanations. Samuel says: “I usually read the texts we get from our civics teacher alone and silently, but I have realized that I see new things after we have discussed the same text in the classroom.” He adds: “I think these classroom discussions are helpful for both me and my classmates, because it makes it possible to know how different people feel and think about the same things in the text.” Similarly, Amalia states that “discussing interesting topics from different students’ perspectives in the classroom is very educational.” However, she also remarks that when talking about sensitive topics in civics texts, such as war and its consequences, in open classroom discussions, teachers need to be cautious since these topics can evoke thoughts and emotions that not everyone may feel comfortable sharing in the classroom. Amalia raises this as one drawback of open classroom discussions. Camilla, Benjamin, Jens, and Jesper also state that they activate their previous civics knowledge when they read about the main topics in Texts 1 and 2 thanks to their civics teachers’ explanations in Grade 9 and earlier grades. Jens says: “Those occasions when I don’t bother searching for difficult civics-related words on Google are when I remember my teacher’s explanations.” Similarly, Elsa says that “the best way of learning new stuff in civics is by listening carefully during the civics lessons and taking notes when your teacher explains difficult stuff.”

5.5. Civics-related knowledge acquired from the school subject of history

Based on the students’ statements, it is apparent that they not only activate their previous knowledge from the subject of civics in earlier school grades but also incorporate their prior knowledge from the subject of history when interacting with Texts 1 and 2. According to the students, incorporating knowledge from related topics they have read about in history contributes to a more nuanced understanding of civics texts. Martin says: “I like history because I want to know how things were before. This part about taxes reminds me of history lessons where we learned that citizens paid taxes to the king.” In his subsequent statements, Martin is eager to discuss how a similar tax system (paying taxes to the king) would function in Sweden as a modern monarchy. Martin is also interested in reading about dictators in history textbooks and the circumstances and processes that have led a country like North Korea to dictatorship. Similarly, other students emphasize the importance of historical perspectives in discussions about democracy, underscoring its value in understanding the significance of democratic rights and societal progress. For instance, Amalia says: “I think it’s important to be reminded that democracy is not achieved on its own, it required a lot of effort and hard to get to where we are today; we’ve learnt about this in history lessons.”

5.6. Knowledge acquired from Swedish language class and diverse textual reading

Another type of prior knowledge that L2 students bring to Texts 1 and 2 is, according to them, their Swedish language knowledge, acquired from the Swedish language classes. For instance, Viktoria says, “Good support from my Swedish teacher has not only helped me read civics texts systematically to find the main parts, but it has also guided me in structuring my own texts and oral presentations.” Viktoria, as well as Daniel, Martin, Camilla, Simon, Elsa, Sara, and Julia, remark that reading different types of texts in Swedish helps them become better at identifying the central parts of the texts, which they find to be an effective and time-saving strategy. For instance, Daniel says: “Reading novels with my mom when I was younger has taught me to become a quicker reader by finding the clues in texts.” Similarly, Viktoria says: “While reading this text [Text 1], it reminded me of Romeo and Juliet, which we read in our Swedish class. It made me think about cause and effect when considering the consequences of our own actions.” According to Camilla, Elsa, and Sara, reading and writing in Swedish language classes not only helped them improve their proficiency in the Swedish language but also taught them how to identify important elements, which they often refer to as “clues,” in texts they read within various school subjects, including civics. Learning how to find the clues in complex school texts also seem to facilitate understanding of difficult words by guessing their meaning from the context in which they are embedded.

5.7. Knowledge obtained from participating in workshops arranged by the school to support students with their school assignments

Only three students report that they actively participate in the workshops arranged by the school, aimed at supporting students with their school assignments. These three students give insufficient parental support as their primary reason for attending these workshops in addition to receiving support from their civics teachers and other teachers in the classroom. Adam, one of these three students, mentions that despite finding the workshops beneficial, not all students participate in them due to the fear of being labeled as a less proficient student by their classmates.

5.8. Additional observations from the analysis

In addition to the seven categories previously discussed, it is noteworthy that two unexpected and intriguing patterns emerge when analyzing the students’ statements about Texts 1 and 2. These two approaches, here called gender-related reflections and cross-national comparisons, appear to be central to the students’ engagement with the texts. Gender-related reflections center on issues of gender and equity, topics that students find particularly engaging when discussing topics such as freedom of choice in Text 1 and democratic rights in Text 2. Cross-national comparisons pertain to comparisons between Sweden and other countries in relation to topics like democracy, censorship, and human rights in Text 1, and free elections, political engagement, democratic rights, and voting procedures in Text 2. Additionally, it is important to highlight that, when reflecting on gender-related issues and making cross-national comparisons in Texts 1 and 2, the students draw on various types of prior knowledge and do not confine themselves to a single type at a time. They appear to engage with multiple forms of prior knowledge simultaneously. This diverse activation of prior knowledge appears to be a result of the students’ accumulated knowledge across various areas (Categories 1–7) throughout their school years. The quotations from students provided in the following two sections (5.8.1. and 5.8.2.) can be seen as supporting this statement.

5.8.1. Gender-related reflections

Several students bring their existing knowledge of the circumstances faced by women and young girls to Texts 1 and 2 when they talk about topics such as freedom of choice and human rights, with which they associate the central concept of democracy in the texts. For instance, Tim and Samuel discuss the plight of women and girls in countries like Iran and Afghanistan, while Amalia reflects on gender inequality in Sweden which, according to her, is not extensively addressed in Text 1. Amalia expresses her dissatisfaction with Text 1, which, according to her, has omitted important concepts, particularly those related to gender inequality in Swedish society. She says: “I’m disappointed with this text because it doesn’t teach me effective argumentations that I can use to stand up for my rights as a woman when my classmates make stupid remarks about women in the classroom.” In Text 2, Emma, Amalia, and Daniel focus on the low participation of single mothers in Swedish elections, attributing it to various factors such as lack of confidence in politicians and single mothers’ prioritization of everyday challenges. These students advocate for political engagement and empowerment of marginalized groups, such as single mothers to address societal injustices within society. For instance, Emma says: “Single moms who are bearing all responsibilities alone may feel that politicians have no understanding of their difficult situation, […] they have no confidence in the politicians, and therefore they don’t vote.” Similarly, Daniel explains that by acknowledging the hardships that many single mothers face, politicians would potentially gain more votes. He says: “Maybe parties which value feminism should target single moms to win more votes.”

5.8.2. Cross-national comparisons

Cross-national comparisons occur when students compare specific topics in Text 1 and 2 that interest them. They try to recontextualize these topics within the context of other countries that they have some knowledge of. When doing this, the students strive to identify differences and similarities between different national contexts. The comparisons are initiated when students come across an image or an explanation in the texts that reminds them of something similar in other geographical and cultural contexts with which they are familiar. For instance, Simon refers to one of the images in Text 1, illustrating two young children and says that this picture reminds him of children in other parts of the world who might not have a smile on their lips due to the poverty and hardships they struggle with daily ().

Figure 2. This image in Text 1 is linked to a section in the text about the freedom of choice in Sweden regarding the number of children in families.

Censorship is another topic in Text 1 that several students engage with. For instance, Samuel expresses his concern about the consequences of not being able to express one’s thoughts freely due to censorship and says: “Dictators love censorship, because they can control things being said about them that they don’t approve of.” Similarly, Tim is worried about young people his age in Iran and North Korea who cannot listen to the music they like or watch a movie without someone cutting out the scenes they find inappropriate.

In Text 2, the section about the low participation rate in elections among specific social groups is a recurring topic to which the students draw several cross-national connections. For instance, Simon raises concerns about the omission of important factors, such as the rate of literacy abilities among marginalized social groups, listed in Text 2. Simon emphasizes the importance of being able to read and understand the ballots and political advertisements from various parties as a critical factor in making informed voting decisions. He further explains that illiterate people in his father’s country of origin are excluded from elections because of their inability to read and write. Simon says: “These individuals genuinely need improvements in their lives, but unfortunately their voices won’t be heard because they don’t vote.” He further says, “people who cannot read and write are easier targets for propaganda, potentially leading them to vote for a party they may later regret.”

Furthermore, from the students’ statements above, it can also be understood that their engagement with Texts 1 and 2 extends beyond gender-related and cross-national perspectives. Their interest in political and societal issues, desire for positive societal changes, and personal goals, such as improving civics knowledge and academic success, also facilitate activation of their prior knowledge to enhance comprehension of civics texts. An overview of the results is presented in .

6. Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that L2 students utilize various types of prior knowledge when engaging with Texts 1 and 2, facilitating their understanding of these civics textbook texts. Each type of knowledge (Categories 1–7) plays a significant role in facilitating the students’ comprehension of Texts 1 and 2. However, not all types of prior knowledge prove equally influential in supporting students to activate the necessary knowledge for understanding the civics texts. According to the students, it is not always easy for them to discern what prior knowledge they should activate and bring to civics texts to better understand them. This suggests the need for targeted guidance from civics teachers to help students activate pertinent prior knowledge effectively when engaging with civics texts. On a practical level, teacher support would involve the integration of civics-related literacy activities (e.g., reading, writing, listening, and speaking activities) tailored to encourage L2 students in leveraging their prior knowledge from various sources when encountering civics texts. As articulated by the students in this study, engagement in pre-, during-, and after-reading activities under the guidance of civics teachers would facilitate the students in making connections between new information in civics texts and their prior knowledge. As an example of such activities, the students highlight classroom discussions, through which they can exchange knowledge and experiences with their peers and civics teachers. According to the students, open classroom discussions not only support them in gaining in-depth understanding of key civics concepts in the texts by exploring these concepts from various perspectives but also enable them to engage with civics texts more confidently. The students’ confidence was palpable when they utilized their prior knowledge and integrated new information from Texts 1 and 2 to effectively communicate their viewpoints during the TA sessions. Furthermore, there appears to be a relationship between the civics topics in Texts 1 and 2 and the extent to which L2 students activate their prior knowledge. For example, during the TA sessions, students actively engaged in discussions about topics such as democracy, human rights, gender equity, and justice with Author 1, showcasing their initiative and autonomy in exploring complex concepts which sparked their curiosity and interest. Despite facing language-related challenges in Texts 1 and 2 (e.g., difficult vocabulary and complex sentence structures), the students were able to comprehend the content by building upon their prior knowledge. Furthermore, the findings show that it is not only the exchange of knowledge and experiences through open classroom discussions that L2 students find beneficial for their comprehension of civics texts. The findings also emphasize the importance of after-reading activities, such as writing assignments and oral presentations that enable the students to apply newly acquired civics knowledge, retrieved from the civics texts, in their own language production. The students report that engaging in these classroom activities provides them with valuable opportunities to deepen their grasp of civics concepts and develop a more nuanced and articulate approach to expressing their viewpoints when discussing civics issues in their written assignments and oral presentations. The findings further suggest that civics teachers can effectively bridge the gap between abstract concepts and the practical application of these concepts in civics by designing activities that foster meaningful discussion and reflection. Additionally, such approaches have the potential to improve the literacy abilities of L2 students, including writing and speaking. Furthermore, it is evident that L2 students show a strong preference for civics topics that resonate with their own interests and experiences. This preference became apparent during the TA sessions when the students engaged with cross-national comparisons, such as reflecting on electoral processes in Sweden compared to other nations. Through these comparisons, students demonstrated a keen ability to apply the content from the civics texts in their reasoning about the diverse expressions of democratic principles within practical contexts familiar to them. The findings also indicate that previous knowledge and education from earlier school years, particularly in subjects like history, play a significant role in students’ understanding and interpretation of civics texts in Grade 9. In line with previous research, the findings suggest that students draw upon their accumulated knowledge from previous grades to better comprehend civics texts (Alexander, Citation2005). Specifically, the students rely on knowledge from history and civics lessons from earlier grades, as well as notes and explanations provided by teachers, to navigate complex civics texts effectively. This underscores the importance of building a strong foundation of knowledge in related subjects throughout a student’s education, as this appears to serve as a valuable resource for understanding and engaging with civics content in later grades. This, in turn, underscores the indispensable role of teachers in earlier school grades in conveying and contextualizing knowledge, thereby facilitating students’ ongoing development in civics throughout Grade 9. Additionally, parental narratives emerge as another influential factor in shaping students’ perspectives on civics topics presented in the civics texts, highlighting the need for educators to acknowledge and leverage these narratives to enrich students’ civics learning (see also Duek, Citation2017).

In conclusion, the findings of this study highlight the significance of tailored instructional methods that harness prior knowledge, integrate meaningful activities, and foster a supportive learning environment to enhance L2 students’ engagement with and comprehension of civics texts. The insights gleaned from L2 students during the TA sessions underscore the effectiveness of activating prior knowledge, drawn from various sources, in mitigating language and content-related challenges encountered with civics texts. Significantly, as students effectively tapped into their prior knowledge, their reasoning about the civics topics presented in Texts 1 and 2 became more nuanced, allowing them to overcome language-and content-related obstacles with greater ease. The students actively expressed a desire for the incorporation of civics-related literacy activities within civics classrooms. Such activities facilitate students’ acquisition of the discipline-specific language commonly encountered in civics texts, with the guidance and support of their civics teachers (see also Rinnemaa, Citation2023a, Citation2023b). Moreover, by recognizing the linguistic proficiency of L2 students, civics teachers can leverage this asset by constructing assignments that foster collaboration between students and their parents, who offer valuable insights from their experiences from living in different countries. With the support of bilingual resources and parental engagement, students can delve into civics topics from diverse viewpoints, thereby enhancing their comprehension of civic issues. This approach not only supports L2 students but also facilitates the learning of L1 students, who gain insights into alternative perspectives through their peers.

Finally, the significant role of teachers in L2 students’ civics learning cannot be overstated. L2 students’ reservations about online discussions underscore the importance of having access to civics teachers who provide accurate information, clarify misconceptions, and foster critical thinking skills among their students. The findings indicate that L2 students rely on their teachers not only for correct information but also for guidance and encouragement to engage in thoughtful conversations on civics issues (see also Jaffee, Citation2016, Citation2022; Wedin & Aho, Citation2022). In contrast to previous research indicating that L2 students struggle with reading comprehension due to their insufficient level of prior knowledge (Beck & McKeown, Citation1991; Clinton et al., Citation2020), our study suggests that challenges with civics texts may arise not from a lack of prior knowledge among L2 students, but rather from the few opportunities they receive to activate and build upon their prior knowledge when engaging with civics texts. It also suggests that an interplay between the four components, illustrated in the four-field model (), could be pertinent for civics teachers to consider when identifying possible difficulties posed by civics texts (see also Rinnemaa, Citation2023c).

Ethical approval

The Swedish Ethical Review Authority has approved this study (Dnr 2021-03734).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the students who participated in the study despite the restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Catherine MacHale Gunnarsson for offering suggestions regarding the language. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available upon request.

Notes

1 Second language (L2) refers to the language that students acquire in addition to their first language(s) either during early childhood or after immigrating to a new country. In Sweden, Swedish is the official language for education. Since L2 students in some classroom settings in parts of the world other than Sweden may be homogenous with regard to their L1, for instance in Spanish-English bilingual classrooms in the U.S.A. where all L2 students may have Spanish as their common L1, the term linguistically diverse students is used in the title of this paper to emphasize the variety of linguistic backgrounds among the L2 students in question here. The group of students in this study speak nine different L1s in total.

2 Expository texts are non-fiction and are meant to inform, explain, or describe a topic or theme to the reader. They are typically written in a clear and organized manner, presenting facts, information, and concepts in an objective way (Clinton et al., Citation2020).

3 The same interview guide has been used in another study by Author 1 (2023b) to explore possible sources of L2 students’ language- and content-related difficulties with reading and understanding Texts 1 and 2.

4 When the participants were orally informed that their real names would be removed in the study due to the ethical principles, some of them wished to be called by names similar to their classmates who had Swedish as a first language. This wish has been respected when choosing pseudonyms.

5 Both textbooks are published by Gleerups, which is a Swedish educational publishing company that produces a wide range of educational materials, including textbooks, digital resources, and other learning materials.

6 Diverse textual reading refers to the practice of engaging with a variety of texts that encompass different genres, styles, perspectives, and topics.

References

- Afflerbach, P., & Johnston, P. (1984). Research methodology on the use of verbal reports in reading. Journal of Reading Behavior, 16(4), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/10862968409547524

- Alexander, P. A. (2005). The path to competence: A lifespan developmental perspective on reading. Journal of Literacy Research, 37(4), 413–436. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/ https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3704_1

- Barton, D. (2017). Literacy: An introduction to the ecology of written language. John Wiley & Sons.

- Beck, I. L., & McKeown, M. G. (1991). Research directions: Social studies texts are hard to understand: Mediating some of the difficulties. Language Arts, 68(6), 482–490. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41961894 https://doi.org/10.58680/la199125316

- Blankvoort, N., van Hartingsveldt, M., Laliberte Rudman, D., & Krumeich, A. (2021). Decolonising civic integration: A critical analysis of texts used in Dutch civic integration programmes. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(15), 3511–3530. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2021.1893668

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brown, C. (2007). Strategies for making social studies texts more comprehensible for English language learners. The Social Studies, 98(5), 185–188. https://doi.org/10.3200/TSSS.98.5.185-188

- Cairney, T. H. (2003). Literacy within family life. In Hall, N., Larson, J., & Marsh, J. (Eds.), Handbook of early childhood literacy (pp. 85–98). Sage

- Chambliss M., Richardson W., Torney-PurtaJ., & Wilkenfeld B. (2007). Improving textbooks as a way to foster civic understanding and engagement (CIRCLE Working Paper 54). Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE).

- Charters, E. (2003). The use of think-aloud methods in qualitative research an introduction to think-aloud methods. Brock Education Journal, 12(2), 68–82. https://doi.org/10.26522/brocked.v12i2.38

- Cho, S., & Reich, G. A. (2008). New immigrants, new challenges: High school social studies teachers and English language learner instruction. The Social Studies, 99(6), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.3200/TSSS.99.6.235-242

- Clinton, V., Taylor, T., Bajpayee, S., Davison, M. L., Carlson, S. E., & Seipel, B. (2020). Inferential comprehension differences between narrative and expository texts: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Reading and Writing, 33(9), 2223–2248. https://link.springer.com/article/ https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-020-10044-2

- Dabach, D. B. (2015). "My student was apprehended by immigration”: A civics teacher’s breach of silence in a mixed-citizenship classroom. Harvard Educational Review, 85(3), 383–412. https://doi.org/10.17763/0017-8055.85.3.383

- Dabach, D. B., Fones, A., Merchant, N. H., & Adekile, A. (2018). Teachers navigating civic education when students are undocumented: Building case knowledge. Theory & Research in Social Education, 46(3), 331–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2017.1413470

- Deltac, S. M. (2012). Teachers of America’s immigrant students: Citizenship instruction for English language learners [Doctoral dissertation]. Emory University. Emory University Theses and Dissertations Archive. https://etd.library.emory.edu/concern/etds/6q182k28d?locale=en.

- De Oliveira, L. C., & Obenchain, K. M. (Eds.). (2017). Teaching history and social studies to English language learners: Preparing pre-service and in-service teachers. Springer.

- Di Stefano, M., & Camicia, S. P. (2018). Transnational civic education and emergent bilinguals in a dual language setting. Education Sciences, 8(3), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8030128

- Dianti, P., & Fatihah, H. (2021). The effectiveness of the use of contextual-based textbook on civic education course [Paper presentation]. 4th Sriwijaya University Learning and Education International Conference (SULE-IC 2020) (pp. 157–160). Atlantis Press.

- Dong, Y. R. (2017). Tapping into English language learners’ (ELLs’) prior knowledge in social studies instruction. The Social Studies, 108(4), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377996.2017.1342161

- Duek, S. (2017). Med andra ord: Samspel och villkor för litteracitet bland nyanlända barn [In other words: Exploring newly arrived children’s participation in literacy practices] [Doctoral dissertation]. Karlstads University.

- Duke, N. K. (2020). When young readers get stuck. Educational Leadership, 78(3), 26–33. https://surreyschoolsone.ca/cms-data/depot/depot/When-Young-Readers-Get-Stuck.pdf.

- Duke, N. K., Ward, A. E., & Pearson, P. D. (2021). The science of reading comprehension instruction. The Reading Teacher, 74(6), 663–672. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1993

- Epstein, S. E. (2020). Supporting students to read complex texts on civic issues: The role of scaffolded reading instruction in democratic education. Democracy and Education, 28(2). 1−12 https://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol28/iss2/3/.

- Ericsson, K. A., & Simon, H. A. (1993). Protocol analysis: verbal reports as data. London: MIT Press.

- Fox, E., & Parkinson, M. M. (2017). Domain explorations of the model of domain learning-reading. In H. Fives & D. L. Dinsmore (Eds), The model of domain learning: Understanding the development of expertise (pp. 89–107). Routledge.

- Gee, J. P. (2001). Discourse and sociocultural studies in reading. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Methods of literacy research (pp.129–142). Routledge.

- Gibson, M. L. (2017). De los derechos humanos: Reimagining civics in bilingual & bicultural settings. The Social Studies, 108(1), 10–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377996.2016.1237465

- Gibson, B. (1997). Talking the test: Using verbal report data in looking at the processing of cloze tasks. Edinburgh Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 8, 54–62. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED409713.pdf.