ABSTRACT

Paid parental leave offerings in the United States are relatively rare and unequal. Yet, little is known about public opinions about paid leave and the factors that distinguish adults’ attitudes about them. With the use of data from the General Social Survey, we investigated attitudes about paid parental leave availability, preferred lengths of paid leave offerings, and government funding of leave in the United States. We found overwhelming support for paid parental leave availability, an average preference for four months of paid leave offerings, and common support for at least some government funding for leaves. Older and more politically conservative individuals were consistently less supportive of paid parental leave availability, longer lengths of leave, and government funding of leave. Women, supporters of dual-earner expectations, black individuals, and those who were not working in paid labor were typically more supportive of generous paid parental leave offerings. These findings suggest that there have been longstanding desires for more widespread and generous paid parental leave offerings in the United States but that this has not yet been sufficient to prompt widely applicable policy changes across the nation.

Researchers are increasingly recognizing the usefulness of paid parental leave. For example, there is evidence that paid parental leave helps to maintain similar levels of household income during spells of caregiving needs surrounding a birth, supports mothers’ continued labor force participation after a birth, and helps to alleviate work-family conflicts (Baum and Ruhm Citation2016; Byker Citation2016; Gault et al. Citation2014; Petts and Knoester Citation2019; Stancyzk Citation2016). Moreover, scholars find that paid parental leave is associated with health benefits for both mothers and infants (Aitken et al. Citation2015; Bullinger Citation2019; Gault et al. Citation2014; Tanaka Citation2005). For instance, empirical evidence indicates that the introduction of the California Paid Family Leave program gave rise to an escalation in exclusive breastfeeding and a decline in infant hospitalization (Hamad, Modrek, and White Citation2019; Huang and Yang Citation2015; Pihl and Basso Citation2019). Furthermore, paid parental leave, when taken by fathers, seems to lead to enhanced levels of paternal involvement in children’s lives, the quality of father-child relations, the quality of parents’ relationships, and parents’ relationship stability (Knoester, Petts, and Pragg Citation2019; Petts, Carlson, and Knoester Citation2020; Petts and Knoester Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2020).

Yet, in spite of the apparent benefits of paid parental leave, its accessibility is rare and uneven in the United States. In fact, the United States is the only Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country in the world that lacks a national mandate for paid leave (Gault et al. Citation2014; Koslowski et al. Citation2020; Raub et al. Citation2018). Relatedly, there are plentiful restrictions on the existing provisions for (both paid and unpaid) parental leave-taking from employers and governments in the United States, so that paid parental leave offerings are largely a function of privilege, disproportionately available to advantaged families of higher socioeconomic status positions (Han, Ruhm, and Waldfogel Citation2009; Harrington et al. Citation2014; Klerman, Daley, and Pozniak Citation2012). For example, fathers who have professional jobs have a higher chance of working for employers that provide paid parental leave, compared to fathers in labor occupations (Bygren and Duvander Citation2006; Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel Citation2007; Williams, Blair-Loy, and Berdahl Citation2013). Although previous research offers a general description of parental leave practices in the United States and its benefits (e.g., Gault et al. Citation2014; Klerman, Daley, and Pozniak Citation2012; Petts, Knoester, and Li Citation2020), scholars have yet to fully investigate public opinions about paid parental leave in the United States and the factors associated with these opinions. Largely, this is because public opinion data about U.S. adults’ support for paid parental leave policies are sparse and overwhelmingly descriptive (Knoester and Li Citation2021; Petts et al. Citation2020; Valarino et al. Citation2018).

The present study uses national data from the General Social Survey (GSS) and draws upon welfare attitudinal theorizing and research (e.g., Blekesaune and Quadagno Citation2003; Chung and Meuleman Citation2017; Mischke Citation2014; Valarino et al. Citation2018) to describe and analyze U.S. public opinions on paid parental leave availability for the parents of a new child, desired lengths of paid leave offerings, and government funding for paid leaves. Specifically, we focus upon the institutional, self-interest, and ideational foundations for leave preferences. In our analysis, we first describe public opinions about the widespread provision of paid parental leaves, how long such offerings should be, and whether or not there should be some government funding for them. Then, we use regression analyses to focus on the extent to which social forces that are linked to gender, work, and family ideologies, commitments, and inequalities predict variation in paid parental leave attitudes. Little is known about the predictors of U.S. public opinions on paid parental leave attitudes; we consider the extent to which gendered expectations, work commitments, and family contexts may shape individuals’ attitudes toward paid parental leave offerings in the United States.

This line of research is particularly necessary due to the seismic shifts in mothers’ labor force participation rates over the past 50–70 years—and the lack of institutional, behavioral, and policy changes that have emerged to adequately support households that are now largely reliant on mothers’ incomes in addition to, or in lieu of, fathers’ incomes (Glynn Citation2016; Pew Research Center Citation2018). Workplaces continue to be gendered institutions that assume male employees can fully commit to working long hours as their female partners are fulfilling caregiving needs at home (Acker Citation1990; Risman Citation1998; Stone Citation2007). Yet, mothers of young children are now nearly twice as likely to be working in paid labor than a generation ago; also, male-solo-breadwinning families have become half as common. In fact, male-solo-breadwinning family structures are a relative rarity nowadays (Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie Citation2006; Cherlin Citation2014; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004).

Although fathers have increased their caregiving contributions substantially over the past few decades (Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie Citation2006; Pew Research Center Citation2019) and increasingly express an interest in paid leave opportunities themselves (Harrington et al. Citation2014; Petts et al. Citation2020), mothers continue to perform the vast majority of childcare and household labor—even while working in paid labor (Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie Citation2006; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004). Furthermore, after a birth, fathers generally take only one week or less of leave compared to ten weeks for mothers, making the unequally gendered division of household labor more uneven after a birth and setting a precedent for an unequal division of domestic labor, moving forward (Hochschild and Machung Citation1989; Petts and Knoester Citation2018; Pragg and Knoester Citation2017; Yavorsky, Kamp Dush, and Schoppe-Sullivan Citation2015). Regardless, work-family conflict is generally amplified for all new parents. Thus, gender inequalities and family strains are frequently substantial after the birth of a newborn, especially for dual-earner households, while the policy solutions that seek to address them are notably absent (Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Raub et al. Citation2018). Paid parental leave is a policy that has the potential to substantially improve the quality of life for families and at least temporarily alleviate work-family conflicts for parents.

Thus, our interest in public opinions about paid parental leave surrounds trying to better understand why the United States is an outlier in its lack of a national mandate for paid leave offerings—and perhaps is willingly missing out on many of the apparent benefits of paid leaves—as well as why and how gendered expectations, work commitments, and family contexts may matter for opinions about family policies such as paid parental leave. That is, does the United States not have a national, paid leave mandate because public opinions do not support such offerings? In order to pursue answers to this question, we need to have a better understanding of public opinions about paid leave offerings and the factors that seem to influence these opinions, first.

The best publicly available data for our analysis is the 2012 GSS, which uniquely asked about paid leave offerings in that year. Although these data are not new, they enable us to pursue answers to our research questions and further trace the extent to which public opinion support for paid leave offerings may have been longstanding—at least, since 2012. The strength and duration of public opinion support for widespread and generous paid leave offerings are both necessary to recognize if there is reason to believe that U.S. adults’ paid leave preferences are not being met, particularly because public support for paid leave has likely only increased since these data were collected.

Most recent research has only offered descriptive summaries of attitudes (e.g., Pew Research Center Citation2017). Also, previous research that has analyzed the most in-depth U.S. data on paid parental leave preferences, with advanced statistical analyses applied to the most recent publicly available information from the 2012 GSS, has either focused on cross-national comparisons (e.g., Valarino et al. Citation2018) or on paid leave for men (e.g., Petts et al. Citation2020). We advance this work in several important ways. We offer new understandings of U.S. paid parental leave public opinions by more comprehensively analyzing a range of attitudes on paid leave (i.e., support for the availability of paid parental leave, desired months of leave availability, and preferences for government funding of leaves) and highlighting new and more detailed indicators of gender, work, and family ideologies, commitments, and inequalities that shape leave attitudes.

Our work offers new information by assessing the extent to which U.S. adults support any paid leave, more precisely measuring preferred lengths of leave (in contrast to the use of multi-month categories that may not accurately capture American perceptions of “long” leaves), and analyzing differences between individuals who supported some government funding of leave with those who did not. Beyond these distinctions, we utilize more extensive indicators of gender, work, and family ideologies, commitments and inequalities to analyze U.S. adults’ leave preferences. Notably, we also advance research on paid leave preferences in the present study by considering gender ideology as multidimensional and correspondingly using nuanced indicators of multiple dimensions of gendered parenting attitudes instead of utilizing a single construct of gender ideology. Thus, our research offers additional insights into U.S. adults’ public opinions about paid parental leave offerings. This is particularly important because of the uniqueness of the U.S. context and its lack of widespread, generous, and institutionalized paid parental leave supports.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The conceptual framework for this study is adapted from welfare attitudinal theorizing and research that emphasizes institutional, self-interest, and ideational factors. Institutional factors consist of the characteristics, structures, and policies within nations (Blekesaune and Quadagno Citation2003; Mischke Citation2014). Self-interest factors involve circumstances that lead individuals to endorse ideas and practices that they presume will benefit them personally (Chung and Meuleman Citation2017). Ideational factors include subjective perceptions that involve ideologies, attitudes, or perceptions of need (Knijn and van Oorschot, Citation2008; Lewin-Epstein et al. Citation2000; Valarino et al. Citation2018).

In terms of an institutional context, we perceive the United States to be an outlier among nations in its lack of guaranteed paid parental leave offerings due to the rise and prominence of neoliberalism, an emphasis on wealth preservation and corporate profits, and political influence that may be unsympathetic to the usefulness of paid parental leave policies for most Americans. Yet, our analysis in the present study focuses upon the individual-level characteristics of U.S. adults in the general population and how these characteristics are linked to adults’ attitudes about paid parental leave offerings. Based on self-interest and ideational factors, we anticipate that the U.S. public will strongly endorse the provision of generous paid parental leave offerings and will substantially support government funding for at least a portion of the leave offerings. Self-interest and ideational factors that involve gender, work, and family, and are linked to inequalities in these realms, are expected to be especially important factors in predicting attitudes about paid parental leave availability, desired lengths-of-leave offerings, and government funding of leaves.

The U.S. Institutional Context and Paid Parental Leave Offerings

The United States, despite its wealth, is a notable exception among countries throughout the world in failing to legislate a national paid parental leave program (Koslowski et al. Citation2020; Valarino et al. Citation2018). Although a handful of U.S. states provide specific laws that can be used for paid parental leave, the only national provisions for parental leave stem from the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA)—which simply covers unpaid parental leave-taking. FMLA allows employees to take unpaid leave of at most 12 weeks for family or medical issues including childbirth. These benefits are restricted to employees who worked for no less than 1,250 hours for employers of at least 50 employees the previous year (Han and Waldfogel Citation2003; Klerman, Daley, and Pozniak Citation2012; Koslowski et al. Citation2020; Winston Citation2014). Consequently, approximately 40 percent of employees are not eligible to take advantage of FMLA for leave benefits and less than 20 percent of private worksites are covered by FMLA in the United States (Klerman, Daley, and Pozniak Citation2012; Winston Citation2014).

Of course, although unpaid leave can be useful, it does far less to help alleviate work-family conflicts and economic pressures, compared to paid leave. In fact, there is evidence that nearly half of all employees who need to take family or medical leave do not do so because of the economic costs of unpaid leave. Relatedly, leave take-up rates are increased substantially when higher levels of wage replacement are instituted in paid leave offerings (Milkman and Appelbaum Citation2013; Raub et al. Citation2018). However, access to paid parental leave is primarily determined by employers in the United States and paid parental leave benefits provided by employers are extremely restricted, only being offered to around 20 percent of all U.S. employees (Bureau of Labor Statistics Citation2020; Pew Research Center Citation2017). Altogether, around 30 percent of U.S. workers seem to have some access to paid leave-taking through various means that appear to include the use of sick and/or vacation days (Petts et al. Citation2020; Valarino et al. Citation2018).

There is evidence from previous research that Americans are very supportive of paid parental leave offerings (e.g., Petts et al. Citation2020; Pew Research Center Citation2017; Valarino et al. Citation2018). This suggests that the U.S. institutional context is not only unusual because of its scarce availability of paid parental leave and lack of a federal paid parental leave policy, but also that it is unique because the lack of institutionalized leave offerings does not seem to match Americans’ preferences. Although we do not focus our analysis in the present study on why this mismatch may exist, it is nevertheless important to consider why such a mismatch may exist in order to rectify how the public may have become supportive of an important family policy, yet the family policy has not been instituted—even after widespread support for it over many years. Such an exercise can help to clarify the U.S. institutional context and its characteristics. We posit that the expected mismatch between public opinions and policy inaction is a function of the rise of neoliberalism, concerns about wealth preservation and corporate profits, and disproportionate political influence by elites who are less sympathetic to the usefulness of paid parental leave policies.

First, the rise of neoliberalist politics in the United States seems to be a primary reason for the lack of a federal paid parental leave policy. Economic conservatives have continued to push for market and individualist solutions to social challenges in recent decades and have tended to resist calls for federal economic investments in social policies—including family-oriented social policies (Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Peck Citation2010; Pfau-Effinger Citation2005; Valarino et al. Citation2018). Thus, there has been substantial political resistance to paid parental leave policies at the federal level and a lack of consideration of such policy initiatives, generally (Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Petts et al. Citation2020; Stier, Lewin-Epstein, and Braun Citation2001; Valarino et al. Citation2018).

Second, concerns about wealth preservation and corporate profits act as obstacles to instituting federal paid parental leave policies. Economic conservatives, anti-tax advocates, investors, and business owners are generally resistant to proposals to institute paid parental leave offerings because of concerns about their funding costs, potential disruptions to workers’ efficiencies, and financial redistribution implications (Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Milkman and Appelbaum Citation2013; Pfau-Effinger Citation2005). Consistent with this, despite recent increases in the provision of leave offerings, the majority of employers in the United States still do not offer paid parental leave to their employees (Mercer Citation2019).

Third, disproportionate political influence is wielded by elites who may be less sympathetic to the usefulness of paid parental leave policies (Cramer Citation2016; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Petts et al. Citation2020; Valarino et al. Citation2018). Indeed, there is evidence that the institution of social policies depends on the influence of economic and political elites—and does not primarily depend on the will of the people (Gilens and Page Citation2014; Winters and Page Citation2009). Economic and political elites, who are disproportionally neoliberalist, older men, may be less likely to be supportive of federal paid parental leave policies because they have less need to use them and may have less desire than the general public to have such policies be instituted for others’ use, as well. They are also better able, and are more committed, to enacting lobbying efforts to support their values and interests, and often are able to mobilize and integrate their own interests with those who are not elites (Cramer Citation2016; Gilens and Page Citation2014; Newman and Giardina Citation2011; Winters and Page Citation2009). This trend seems to occur across different social welfare programs, too. For instance, a study that focused on the top 1 percent of wealth holders in the United States found that although 61 percent of the public supports tax-financed, national health insurance, only 32 percent of exceptionally affluent Americans is in favor of it (Page, Bartels, and Seawright Citation2013).

Nevertheless, consistent with previous research findings, we anticipate that public opinions about paid parental leave offerings will overwhelmingly favor paid parental leave availability, support relatively generous lengths of paid parental leave offerings, and favor substantial government funding of paid leaves. Parenting continues to be a primary aspiration and experience for the vast majority of the population; work-family conflicts are common and challenging, attitudes and experiences regarding women in the workforce and father involvement have shown long-term improvements in support, and economic pressures could be temporarily alleviated through paid parental leaves (Cotter, Hermsen, and Vanneman Citation2011; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Petts et al. Citation2020; Raub et al. Citation2018). Yet, gendered expectations as well as family-related strains and ideologies—that may derive from work commitments, family contexts, and background characteristics—are expected to differentiate levels of support for different types of paid parental leave offerings.

Self-Interests, Ideations, and Paid Parental Leave Offerings

Indeed, gendered expectations and family-related strains and ideologies offer self-interest and ideational reasons for particular preferences for paid parental leave offerings. That is, gendered expectations, such as those connected to gendered inequalities and multidimensional gendered ideologies about parenting roles, are likely to differentiate attitudes about paid parental leave offerings. We follow recent research in recognizing the complexity of gender and considering the potential implication of ideologies about: a) dual-earner couples, b) separate spheres of expertise and devotion, and c) intensive mothering (Cotter, Hermsen, and Vanneman Citation2011; Grunow, Begall, and Buchler Citation2018; Hays Citation1996; Petts et al. Citation2020). In addition, family-related strains and ideologies may shape support for paid parental leave availability, desired length of leave offerings, and government funding of leaves; thus, work commitments and family contexts that may be linked to family-related strains are expected to be salient.

First, gendered expectations are anticipated to influence attitudes about paid parental leave. We consider gender identities and gendered ideologies about dual-earner couples, separate spheres, and intensive mothering, in this regard. Gendered ideologies, identities, and expectations are a part of gendered cultures that direct and encourage women to disproportionately embrace and commit to childrearing and domestic tasks, and men to embrace and commit to paid labor activities. Since these gendering processes occur almost automatically and without much reflection, and are institutionalized throughout society, they are often viewed as natural and appropriate (Ridgeway Citation2009; Ridgeway and Correll Citation2004; Risman Citation1998). Still, gendered ideologies, identities, and expectations are continually challenged and are either transformed or reinforced, in different ways (Risman Citation1998; West and Zimmerman Citation1987).

Because of traditionally gendered expectations and prevalent challenges of being in and succeeding in paid work, as well as the particular need for medical recoveries and breastfeeding interactions, we anticipate that women will be more likely to support paid parental leave availability, longer lengths of paid leave offerings, and government funding of leave, on average, compared to men. Beyond expectations and needs, there is also a self-interest factor in terms of behaviors and options, as women are much more likely to take, and be offered, paid leave than men (Gault et al. Citation2014; Heymann and McNeill Citation2013; Klerman, Daley, and Pozniak Citation2012). There is also previous research that supports these expectations for gender differences in attitudes about paid leave, including a greater desire amongst women to have paid paternity leave offered (Petts et al. Citation2020; Valarino et al. Citation2018). Thus, there are reasons to believe that gendered expectations lead to socially patterned gender differences in support for more widespread and generous paid parental leave offerings; of course, there are circumstances, however, where such gender differences may not exist and where individuals’ support for leaves may otherwise vary (e.g., particular family needs and experiences may modify support for leaves; some men may especially want to take leaves).

We also anticipate that attitudes about dual-earner expectations, separate spheres, and intensive mothering will shape preferences for paid parental leave offerings. Previous work finds that traditional gender ideologies are negatively associated with support for paid paternity leave, but positively associated with support for long, paid parental leave offerings (Petts et al. Citation2020; Valarino et al. Citation2018). Yet, different dimensions of gendered parenting role ideologies may be differentially relevant, and uniquely salient in their combinations, as parents adapt different versions of egalitarian attitudes and practice different combinations of breadwinning (e.g., 1-, 1.5-, and 2-earner combinations), separate spheres (e.g., variations in domestic labor commitments with different breadwinning combinations), and intensive mothering (e.g., realized on top of breadwinning and separate spheres arrangements and/or preferences) (Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie Citation2006; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Li, Knoester, and Petts Citation2021).

Dual-earner expectations may lead to a greater perceived need for paid leave availability and funding, but maybe not a particularly lengthy span of leave, due to the need for parents to return to their paid work commitments. In contrast, support for separate spheres of devotion and expertise may encourage disapproval for the existence of paid leaves but also the existence of longer leave offerings in order to support separate spheres for as long as possible. Finally, intensive-mothering expectations may amplify disapproval for paid parental leave offerings but also support long periods of leave-taking for mothers in particular because of the perceived need for mothers to always be present, engaged, and invested as much as possible in their child’s development (Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie Citation2006; Hays Citation1996; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Stone Citation2007). Related to this, although families and especially mothers have adapted in a variety of ways in response to intensive-mothering pressures and motivations (e.g., spending more quality time with children, hiring well-qualified caretakers and educators), a common outcome and historically frequent expectation is for mothers to reduce their work hours or even stay out of the labor force altogether when they have young children (Hays Citation1996; Petts, Knoester, and Li Citation2020; Stone Citation2007). Furthermore, on balance, we anticipate that gendered expectations may especially determine women’s paid leave preferences, since leave offerings are most likely to impact women’s lives (Petts et al. Citation2020; Yavorsky, Kamp Dush, and Schoppe-Sullivan Citation2015). Also, we expect that combinations of multiple dimensions of traditional gender attitudes may exacerbate these patterns of support, or the lack thereof.

Second, family-related strains and ideologies are expected to be associated with preferences for paid parental leave availability, longer lengths-of-leave offerings, and government funding for leaves. That is, family-related strains and ideologies may shape parental leave preferences because of self-interest or empathetic reasons. Consequently, work commitments, family contexts, and background characteristics that may be linked to enhanced or recognized family strains, and a need for family supports such as paid parental leave offerings, are expected to be salient. For example, heightened work commitments to paid labor and unpaid domestic labor may encourage those with enhanced commitments, or the recognized support from a partner with enhanced commitments, to perceive a need for generous paid parental leave offerings for family well-being (Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie Citation2006; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Petts et al. Citation2020; Winston Citation2014). More disadvantaged workers, such as those who are not professionals and have lower earnings, may also be more in need of paid leave offerings (Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Petts et al. Citation2020; Winston Citation2014).

In terms of family contexts, having more children and experiencing frequent work-family conflict may lead individuals to advocate for more generous paid parental leave offerings. For example, having more children may result in a greater real and perceived need for additional family supports upon the arrival of a new child. Similarly, experiencing more work-family conflict could encourage individuals to be more likely to perceive value in more widespread and generous paid leave offerings that could help offset work-family conflicts that become heightened upon the arrival of a new child. Greater recognition that raising children is expensive may also encourage support for more generous paid parental leave offerings as paid leaves can offer essential financial assistance to families (Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie Citation2006; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Li, Knoester, and Petts Citation2021; Petts et al. Citation2020; Winston Citation2014). Religiosity and self-identified conservatism may also be important components of family contexts and are linked to paid parental leave preferences. Religiosity is associated with family contexts; it often sacralizes family commitments and gender traditionalism, for instance (Petts et al. Citation2020). In addition, social conservatives may be especially reticent to institutionalize support for changing gendered expectations and experiences. Whereas, economic conservatives tend to emphasize low-tax, small government as well as personal responsibility and may be especially unlikely to support family social policies, particularly those that are supported by government funding (Cramer Citation2016; Gault et al. Citation2014; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Valarino et al. Citation2018). Thus, we expect that self-identified political conservatism will be negatively associated with support for paid parental leave availability, desired lengths-of-leave offerings, and government support of leaves (Cramer Citation2016; Gault et al. Citation2014; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Valarino et al. Citation2018).

Of course, family- and work-related strains and ideologies that reflect a perceived need for support are also likely to be gendered, based on domestic work burdens and workplace inequalities (Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie Citation2006; Hays Citation1996; Petts et al. Citation2020; Stone Citation2007). In addition, other indicators of disadvantage that include being a racial/ethnic minority and occupying a lower socioeconomic status may enhance family and work-related strains and encourage support for more generous paid parental leave offerings (Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Petts et al. Citation2020; Winston Citation2014). Age is expected to be negatively associated with support for more generous paid parental leave offerings, because of self-interest and family strain reasons; older individuals are less likely to benefit from leave offerings and express a need for them (Petts et al. Citation2020; Valarino et al. Citation2018). Thus, background characteristics such as age, race/ethnicity, and education may predict individuals’ paid parental leave preferences.

Hypotheses

Overall, our conceptual framework and previous research suggests the following hypotheses:

H1: Most respondents will endorse paid parental leave availability, long lengths of paid leave offerings, and government funding of paid leave—despite the unique lack of a federal guarantee of paid parental leave in the U.S.

H2: Gendered expectations will be linked to paid parental leave preferences. Consequently, we anticipate:

H2a: Women, compared to men, will be more likely to support paid parental leave availability, longer lengths-of-leave offerings, and government support for leave.

H2b: Dual-earner expectations will be positively, and separate-spheres and intensive-mothering attitudes will be negatively, associated with support for leave availability and funding; however, separate-spheres and intensive-mothering attitudes will be especially likely to lead to preferences for longer lengths-of-leave offerings.

H3: Family-related strains and ideologies that reflect a need or preference for family policy supports will be positively associated with desires for paid parental leave availability, longer lengths-of-leave offerings, and government funding of leave. Thus, we anticipate:

H3a: Greater paid and unpaid work commitments will encourage support for more generous paid parental leave offerings. Relatedly, more advantaged (e.g., professional and higher-income) workers will be less likely to espouse a need for more generous paid parental leave offerings.

H3b: Family-related contexts and policy-linked factors such as experiencing work-family conflict, recognizing the expense of raising children, and having more children will be positively associated with preferences for generous leave offerings. Self-identified conservatism will be negatively associated with support for paid parental leave availability, longer lengths-of-leave offerings, and government funding of leaves.

H3c: Background characteristics that are expected to be associated with enhanced family strains – such as being a racial/ethnic minority, being younger, and being less educated – are expected to be positively associated with preferences for more generous paid parental leave offerings.

H4: Gendered expectations are expected to interact with one another in predicting paid parental leave preferences. That is, we anticipate that women will be more supportive of leave offerings when they possess attitudes in favor of women’s paid labor. Also, we expect that traditionally gendered attitudes, in combination with one another, will depress support for leave availability and government funding of leaves, but exacerbate support for longer lengths-of-leave offerings.

METHOD

Data come from the 2012 General Social Survey (GSS); the GSS is an annual (or biennial), nationally representative survey of adult Americans. Only the 2012 GSS (N = 1,974) contained a special module on family and changing gender roles, which included questions on attitudes about paid parental leave availability, length of desired leave offerings, and government funding of leaves. To our knowledge, this is the only publicly available data that contain information about adults’ attitudes toward different aspects (e.g., provision, length, funding) of paid parental leave offerings in the United States and further enable detailed analyses of the self-interest and ideational factors that may distinguish adults’ paid parental leave preferences (Petts et al. Citation2020; Valarino et al. Citation2018). Our sample (N = 1,189) was restricted to the random subset of respondents who were asked questions about paid parental leave in the GSS, although respondents who answered “don’t know” about paid parental leave availability (about 5 percent of those asked) were excluded because it was unclear whether or not they supported paid parental leave and they were also not asked the follow-up questions about leave offerings.

Dependent Variables

Our dependent variables include indicators of support for paid parental leave availability, desired lengths of paid leave offerings, and government funding of leaves. In the survey, respondents were asked, “Consider a couple who both work full-time and now have a new born child. One of them stops working for some time to care for their child. Do you think there should be paid leave available and, if so, for how long?” Respondents who supported paid parental leave availability were then asked who should pay for this leave: a) the government, b) the employer, c) both, or d) other sources. Support for paid parental leave availability (1 = yes) represents affirmative responses to the question about whether or not the hypothetical couple should have paid leave available. Desired length of paid leave offerings indicates the number of months of paid leave that respondents reported should be made available to the couple. Finally, government funding of leave signifies whether or not respondents indicated that the government should pay for at least some of the cost of paid leave (1 = yes).

Predictor Variables

Our predictor variables are indicators of gendered expectations and family-related strains and ideologies that reflect the need for more family supports. Gendered expectations are tapped by measures of gender (1 = female) and attitudes about multiple aspects of gendered parenting roles. Parenting role attitudes consist of responses (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) to statements about family life. Dual-earner expectations reflect responses to: “Both the husband and wife should contribute to the household income.” Separate spheres attitudes indicate: “Man’s job is to earn money; a woman’s job is to look after the home and family.” Intensive mothering reveals reactions to: “All in all, family life suffers when the woman has a full-time job.” The parenting role attitudes are modestly to moderately correlated (r’s = .04, .09, and .41; separate-spheres and intensive-mothering attitudes are the most correlated) and do not present collinearity problems into the models, based on the variance inflation factor indicators.

Family-related strains and ideologies that suggest, or encourage recognition of, needs for family supports include measures of work commitments, family contexts, and background characteristics. Paid work measures consist of dummy variables for full-time (35–55 hours), overtime (> 55 hours), part-time (1–34 hours), and no employment. We include measures of whether one has a partner working in paid labor (1 = yes), occupational type (i.e., dummies for professional/service/labor/other), and household income (in $10,000’s – but sensitivity analyses employing logged income, tests for curvilinearity, and categorical thresholds produced nearly identical estimates and no evidence of significant nonlinear results), as well. Unpaid work measures include reports of how many hours per week respondents (and one’s partner, if available) spend on a) housework and b) care of family members. These variables are standardized (M = 0; SD = 1) for the analyses.

Family context variables include reports of work-family conflicts, family structures, and family-related ideologies. We utilize responses to four questions about whether one does or does not experience different aspects of work-family conflict (e.g., family responsibilities lead to trouble concentrating at work; come home from work too tired to do chores, etc.) at least several times a month or more (0 = no work-family conflict, on a monthly basis; 4 = work-family conflict several times per month or more, in all four aspects). Family structure variables include relationship status dummies (i.e., married/cohabiting/single), number of children, and number of children in the household who are under the age of 18 years. For perceptions of the expense of raising children, we use reports (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) of the extent to which respondents think that raising kids is expensive. Finally, our consideration of family-related ideologies involves religiosity and self-identified conservatism. Frequency of religious participation (0 = never; 3 = at least weekly) indicates religiosity. Political conservatism (1 = extremely liberal; 7 = extremely conservative) represents self-identified conservatism.

Background characteristics include age, race/ethnicity and education. Age and education are measured in years. We use mutually exclusive dummy variables (i.e., white, black, latinx, or other) for race/ethnicity.

Analytic Strategy

For our analysis, we initially scrutinize the descriptive characteristics and focus on the extent to which respondents espouse support for paid parental leave availability, relatively long paid leave offerings, and government funding of leaves. Then, we model paid parental leave attitudes, using logistic regressions to predict support for paid leave availability and government funding of leave, and ordinary least-squares regression to predict desired lengths-of-leave offerings. We test for potential interaction effects involving gendered expectations by entering the relevant interaction terms into our full additive models, in separate models. We then graph and present significant interaction effects in our results. If interaction effects emerge, we display illustrations of them with predicted probabilities based on marginal effects. We use multiple imputation results from ten models to address missing data; yet, the findings are consistent with the use of listwise deletion of missing data.

RESULTS

The descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in . As expected, despite the lack of a national paid parental leave policy and sparse access to paid parental leave, there is evidence of overwhelming support for paid parental leave availability. Among respondents who reported a preference for paid parental leave availability for a hypothetical couple, 82 percent indicated support for paid leave availability; 18 percent responded that there should be no paid leave. On average, respondents desired lengths of paid leave offerings to be just over four months in duration; 66 percent of all respondents advocated for between 1–6 months of paid leave and 16 percent of all respondents advocated for more than 6 months of paid leave. In terms of government funding, few respondents (i.e., 6 percent) supported a complete reliance on government funding, but a plurality (i.e., 41 percent) of all respondents indicated that both government and employers should share the costs of paid parental leave; thus, 47 percent of all respondents supported paid parental leave availability as well as at least some government funding of the leave (18 percent supported no funding; 35 percent supported funding from entirely non-government sources). Therefore, there is abundant support for paid parental leave availability, desires for substantial (i.e., over 4 months long, on average) lengths of paid parental leave offerings, and common endorsements of some government funding for paid leaves. To supplement the descriptive findings that are presented in , distributions of adults’ reported preferences for lengths-of-leave offerings and sources of funding for paid leaves are included in the Appendix.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for all Variables Used in the Analysis

Next, we turn to predicting attitudes about paid parental leave. First, as shown in Model 1 of , we predict support for paid parental leave availability. Consistent with our second hypothesis, there is evidence that the odds that women (OR = 1.76, p < .01) support paid parental leave availability are 76 percent higher than those for men. Also, dual-earner expectations (OR = 1.27, p < .01) appear to lead to increased support for paid parental leave. In terms of work commitments, those who are not working have odds of supporting paid parental leave (OR = 2.76, p < .01) that are more than 2.5 times as large as those from adults who are employed full time. This finding was unexpected but may reflect an unfulfilled desire to be active in paid labor, due to family caregiving responsibilities and a recognition that paid leave could facilitate maintaining both paid and unpaid work commitments (Stone Citation2007). As far as family-related predictors, only the ideational indicator of conservatism is significant; conservatism (OR = .76, p < .001) is negatively associated with support for paid parental leave availability, as expected. Finally, background characteristics seem to shape parental leave preference; older (OR = .97, p < .001) respondents are less likely than younger respondents to support paid leave availability, as anticipated. Also, compared to white respondents, black respondents are significantly more likely to support paid parental leave (OR = 2.36, p < .05). There is no evidence of interaction effects between gendered expectations in predicting leave availability.

Table 2. Regression Results Predicting Support, Length, and Government Funding of Paid Parenta Leave

In Model 2 of , we display the results from predicting desired lengths of paid parental leave offerings. In contrast to expectations and cross-national results from other studies (Li, Knoester, and Petts Citation2021; Valarino et al. Citation2018), we find that separate-spheres expectations are associated with shorter desired paid leave offerings (b = −.25, p < .05). Yet, consistent with our second hypothesis, there is some evidence that intensive-mothering expectations are associated with a desire for longer leave offerings (b = −.20, p < .10). In terms of work commitments, not working in paid labor (b = 1.10, p < .05) is once again positively associated with a desire for more generous paid parental leave. We also find that a partner’s hours of housework (b = . 40, p < .05) are positively associated with a preference for longer lengths of leave. Once again, conservatism (b = −.48, p < .001) is the only significant family-related predictor; it is negatively associated with preferred lengths of paid parental leave offerings, as expected. Finally, in terms of background characteristics, age (b = −.02, p < .05) is once again negatively associated, as expected. Also, we find that compared to white individuals, black individuals (b = 1.32, p < .001) desire longer lengths of leave; there is also some evidence that other (b = .86, p < .10) racial/ethnic minorities prefer longer lengths of leave, as well. There is no evidence of interaction effects between gendered expectations in predicting preferred length of leave offerings, either.

Finally, we present the results from predicting support for at least some government funding of paid parental leave, in Model 3 of . In terms of gendered expectations, as hypothesized, there is some evidence that dual-earner expectations are positively associated with support for government funding of paid parental leaves (OR = 1.13, p < .10). Yet, more convincing evidence exists that compared to professionals, labor workers are more likely to support government funding for paid leaves (OR = 1.87, p < .05). As far as family-related predictors, work-family conflict (OR = 1.20, p < .05) and the number of minor children in the household (OR = 1.25 p < .01) are positively associated with supporting government funding of paid parental leave, consistent with expectations. Further, conservatism (OR = .75, p < .001) is negatively associated with supporting government funding of paid parental leave. Finally, in terms of background characteristics, age (OR = .99, p < .05) is negatively associated with support for government funding. Also, there is some evidence that, compared to being white, identifying as latinx (OR = 1.41, p < .10) or another nonblack and nonwhite race/ethnicity (OR = 1.68, p < .10) leads to a greater likelihood of supporting government funding of paid parental leave.

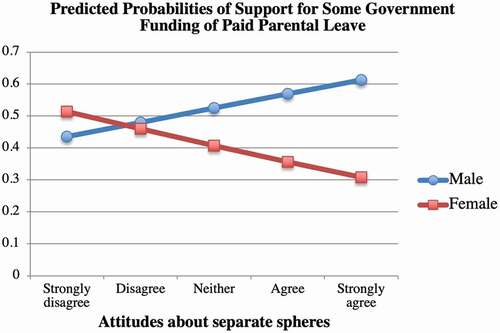

Consistent with our fourth hypothesis, there is evidence of one interaction effect, involving gendered expectations, in predicting government funding of leave. This is displayed in Model 4 of , and its implications are illustrated with predicted probabilities, using marginal effects, in . It seems that the association between beliefs about separate spheres and support for government funding varies by gender; that is, support for separate spheres is positively associated with support for government funding for leave among men, but it is negatively associated with support for government funding among women. One interpretation of this effect is that men who prefer separate spheres may still want to use paid leave themselves and/or see the value in government funding to enable women to stay at home with newborn children—particularly in an era where having two working parents is common. In contrast, women who prefer separate spheres may be less attached to the labor force and consequently may not be as supportive for government funding for leave—especially if they do not perceive such a policy to be personally beneficial. Moreover, due to the history of traditionally gendered divisions of labor, women who believe in separate spheres may perceive childrearing as their natural and appropriate responsibility and may disagree on principle with being rewarded or compensated by the government for fulfilling this task (England Citation2010). It seems that we did not discover interaction effects between gender and either dual-earning or intensive-mothering attitudes because the implications of these for men’s and women’s leave preferences are more aligned with one another (e.g., dual-earning expectations boosts leave desires; in the U.S. context, intensive mothering appears to encourage longer leave offerings to encourage staying home). Relatedly, compared to the near even split in support for government funding of leaves, there is little variance in adults’ preferences for leave availability and an apparent lack of systematically different preferences for lengths-of-leave offerings, in the United States

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the patterns and predictors of U.S. attitudes about paid parental leave. In our analysis, we described the extent of support for paid parental leave availability, different lengths of paid leave offerings, and government funding of paid leaves. Then, we considered the extent to which gender, work, and family ideologies, commitments, and inequalities shape attitudes about paid parental leave availability, desired lengths-of-leave offerings, and government funding of leaves. Our findings indicate overwhelming support for paid parental leave availability, preferences for an average of about four months of paid leave offerings, and common support for at least some government funding of leaves. In addition, there is evidence that gendered expectations are related to paid parental leave preferences. However, predominantly, U.S. attitudes about paid parental leave appear to be associated with age, race/ethnicity, and self-identified conservatism. Unexpectedly, on balance, there was sparse evidence that work and family contexts distinguished respondents’ paid parental leave preferences. Below, we recap the support for our hypotheses and contextualize our findings.

First, despite the lack of a national paid parental leave policy and only scarce access to paid parental leave availability in the United States (Petts et al. Citation2020; Valarino et al. Citation2018), we found overwhelming support for paid parental leave availability, a desire for somewhat generous lengths of paid leave offerings, and common support for government funding of paid leaves. About 80 percent of all respondents reported that a hypothetical couple with a newborn child should have paid parental leave made available to them. On average, there was a preference for four months of paid leave offerings. Finally, nearly 50 percent of the national sample of U.S. adults endorsed at least some government funding of paid parental leaves.

These descriptive results significantly add to the limited research that has been done on attitudes about paid parental leave in the United States. For example, we offer unique indications of support for any paid parental leave availability, precise estimates of preferred months of leave offerings, and evidence of support for some government funding of leaves, compared to previous research that has considered either attitudes about the relative support for different lengths of leave in the United States with these data, in a cross-national comparison, or focused on support for paid paternity leave, specifically (Petts et al. Citation2020; Valarino et al. Citation2018). Our findings from the 2012 GSS also seem to be in line with comparable survey results from late 2016, suggesting that support for paid parental leave has been more longstanding than many people may assume (Pew Research Center Citation2017).

We can further contextualize our descriptive findings by noting that U.S. respondents support lengths-of-leave offerings that are about one month longer—and paid—compared to the existing FMLA guarantee for unpaid leave in the United States This finding is informative for policymakers and parental leave advocates as it portrays a considerable gap between how much leave is currently offered versus desired by the public. It clearly shows that the United States has a long way to go to adequately satisfy people’s needs for paid parental leave, given that even FMLA is not widely accessible to all people and is not paid (Klerman, Daley, and Pozniak Citation2012; Koslowski et al. Citation2020; Winston Citation2014). Yet, there has been increasing awareness of the need for more widespread and generous paid leave offerings in the United States and even some encouraging evidence that marked changes could finally occur. For example, a global pandemic has seemingly shocked substantial numbers of people into recognizing that there are inadequate family supports in place in the United States, and the federal government responded by implementing a paid leave policy. The Families First Coronavirus Response Act passed in March 2020 provided employees with up to 10 weeks of emergency paid family and medical leave. Although the paid leave provision expired at the end of 2020, there are other signs that paid leave policies are gaining momentum. President Trump signed a provision for up to 12 weeks of paid parental leave for federal employees that went into effect in October 2020. In addition, nine states and Washington, DC, passed paid family leave policies with numerous other states proposing similar laws (Gardner Citation2021; Koslowski et al. Citation2020).

Yet, our findings indicate that even though 82 percent of respondents seem to support access to paid leave, only 47 percent of respondents appear to think the government should be involved in the financing of some of the leave offerings. This reluctance to endorse state provisions of benefits reflects a dominant ideology of market fundamentalism in the U.S, which involves a preference for self-regulating markets free from governmental interference (Somers and Black Citation2005). Relatedly, employers express strong opposition against government funding of social programs, such as paid leave, because they are concerned that governments will increasingly influence other aspects of their business after a particular mandate is allowed to be enforced (Milkman Citation2009). This mistrust of state intervention can help to explain why the United States differs from the rest of the world in its lack of a federal mandate for paid leave, despite substantial public support for leave offerings. It also suggests that there is likely to be continued resistance to the passage of more widespread and generous family policy supports, such as paid parental leaves – despite the recent signs of progress (Gardner Citation2021; Koslowski et al. Citation2020). Indeed, in sensitivity analyses, we included a four-item scale of support for state responsibility in providing childcare and elder care (see Valarino et al. Citation2018, for details) and this was positively associated with support for government funding of leaves, as expected.

Second, we found support for our hypotheses about gendered expectations being linked to paid parental leave attitudes. On average, women were much more likely than men to support paid parental leave availability. Dual-earner expectations were positively associated with support for paid leave availability and there was some evidence (i.e., p < .10) that they also increased support for government funding of leaves. There was also some evidence that intensive-mothering attitudes lead to preferences for longer lengths-of-leave offerings. Somewhat unexpectedly, we found that separate-spheres attitudes were negatively associated with preferred lengths-of-leave offerings; this is in contrast to cross-national findings of the opposite association (Li, Knoester, and Petts Citation2021; Valarino et al. Citation2018). It seems that because the lengths of leave preferences are so much shorter in the United States than in other nations, there is little encouragement among U.S. adults who endorse separate spheres to advocate for long leaves if they believe that mothers should be out of the labor force, with young children. In fact, relatedly, we found that gender determines the extent to which separate-spheres attitudes support government funding of paid leaves such that support for separate spheres was negatively associated with support for government funding among women, but positively associated with support for government funding of leave among men.

In sum, because women are thought to especially benefit from paid parental leave offerings (since they are more likely to take leave than men and are more likely to attempt to equally invest in work and family obligations), these findings are notable in highlighting how gendered expectations shape the needs and desires for generous paid leave offerings (Bianchi, Robinson, and Milkie Citation2006; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Stone Citation2007). Yet, they are also notable because men, who also expressed more traditionally gendered expectations for separate spheres and intensive mothering (see ), are overrepresented in positions of power as economic and political elites who disproportionately shape public policies – including policies involving paid parental leave-taking (Cramer Citation2016; Gilens and Page Citation2014; Winters and Page Citation2009). That is, the persons primarily shaping policies are less sensitive to the needs and desires for paid leaves.

Finally, in terms of other family-related strains and ideologies, we found rather sparse and inconsistent evidence that work commitments and family contexts in the United States distinguish support for paid parental leave offerings. Yet, one thing to note is that we find that both number of children in the household and work-family conflicts are positively associated with support for government funding of paid parental leaves. This suggests that individuals who have greater family burdens and strains most recognize a need for more government support of family polices, such as paid parental leaves.

Instead, background characteristics such as age and race/ethnicity were more consistent predictors of leave preferences, compared to family-related strains and ideologies. For example, self-identified conservatism and our continuous indicator of age were consistently and negatively associated with desires for more generous paid parental leaves, as expected. These findings offer new information from the GSS data but are in line with party-affiliation associations from Pew Research Center (Citation2017) and general age-category findings from Valarino et al. (Citation2018). We also found new evidence that compared to whites, black respondents were far more likely to support paid parental leave availability and longer leave offerings. In addition, there was also evidence that not having a job in paid labor increases support for more generous leave offerings, compared to having a full-time job. This may reflect the need for more income and, potentially, the possibility that some workers, among those who are not currently working, left a job because of family responsibilities. In all, as with our gendered-expectations findings, these results are more broadly significant because substantial proportions of especially influential economic and political elites are older and politically conservative (Gilens and Page Citation2014; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Winters and Page Citation2009). Similarly, racial-ethnic minorities and those who are not in paid labor are not well represented by economic and political elites and may especially benefit from paid parental leave offerings; they are disadvantaged in the marketplace and may be especially reticent to take or be able to take leaves (Cramer Citation2016; Knoester, Petts, and Pragg Citation2019; Petts et al.Citation2020; Winters and Page Citation2009).

Still, like all studies, this study has limitations. Clearly, since our data come from 2012, more updated information is needed to extend our inquiries and analyses. Moreover, we are unable to obtain detailed explanations for why respondents expressed support, or a lack thereof, for different aspects of paid parental leave offerings; relatedly, we were unable to inquire about support for unpaid leave policies. In addition, the situation described to respondents in the GSS presents paid parental leave as a family entitlement as it is often characterized in countries with statutory leave policies; however, parental leave generally exists as an individual entitlement in the United States (FMLA, state-level, and most company policies). Further, we would have liked to have a better understanding of respondents’ identities, aspirations, work-family challenges, workplace characteristics, and options for meeting their perceived needs. Similarly, we would have also liked to have more comprehensive measures and more complete understandings of respondents’ gendered expectations. Finally, we do not seek to disentangle attitudes about paid maternity and paid paternity leave, analyze macro-level factors, or further delve into other specific contexts (e.g., mental health, medical, and special needs) that may lead to in-group differences in the present study. These are all fruitful avenues for future research but beyond the scope of this study.

Nonetheless, this study advances research on parental leave in the United States by theorizing about, observing, and describing an enormous disjuncture between public opinions about paid parental leave availability, lengths-of-leave offerings, and government funding of leaves—and extant policies that support paid parental leaves. Through drawing upon welfare attitudinal theorizing and research, we were motivated to closely examine the institutional context under which U.S. adults’ leave preferences and the United States’ unique lack of widespread and generous paid parental leave offerings have emerged (Blekesaune and Quadagno Citation2003; Mischke Citation2014. We were also encouraged to identify and consider the roles that self-interest and ideational factors may be playing in predicting attitudes toward paid parental leave offerings in the United States As part of this focus, we emphasized the significance of gendered expectations, family strains and ideologies, and their links to background characteristics (Chung and Meuleman Citation2017; Knijn and van Oorschot Citation2008; Lewin-Epstein et al. Citation2000; Valarino et al. Citation2018).

The United States is the only OECD country, and one of only a few countries in the world, that has not implemented a national paid parental leave guarantee. Furthermore, in the United States, only a minority of employees work for an employer, or live in a state, that offers paid parental leave (Koslowski et al. Citation2020; Petts et al.Citation2020; Raub et al. Citation2018; Winston Citation2014). Yet, the results from this study suggest that, since 2012, about 80 percent of U.S. adults have supported paid parental leave availability and have endorsed an average paid leave offering of about four months in duration. Furthermore, nearly half of U.S. adults have supported some government funding of paid parental leave, although most endorse also having employers make financial contributions to fund paid leave offerings. Compared to individuals in other wealthy nations, U.S. respondents are only about 10 percent less likely to support paid parental leave availability; however, their desired lengths-of-leave offerings is about one-third of the average preferred length of leave offerings from individuals in comparable nations. Also, U.S. respondents are about 60 percent as likely to support some government funding of leave compared to individuals in countries that have national paid parental leave policies (Knoester, Li, and Petts Citation2021; Petts et al. Citation2020; Valarino et al. Citation2018). Still, a desire for more generous paid parental leave offerings in the United States is apparent.

Related to this, the study improves our understanding of paid parental leave attitudes and policies by finding that older, white men, who are politically conservative, are especially unlikely to support paid parental leave availability, generous lengths-of-leave offerings, and government funding of leaves. Not coincidentally, political and economic elites in the United States are disproportionately older, white, men, who advocate for more economically conservative policy approaches and have used political strategies to garner support to stay in power from citizens who seem to be overwhelmingly in support of paid parental leave, on average (Cramer Citation2016; Gilens and Page Citation2014; Jacobs and Gerson Citation2004; Winters and Page Citation2009). Perhaps, if Americans wish to implement more widespread and generous paid parental leave policies that are consistent with their expressed preferences, they would be more likely to accomplish such goals with elected representatives that are more sensitive to paid parental leave needs. The findings of this study suggest that that may require a shift in the background characteristics and ideologies of a large segment of the political leadership in the United States

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Qi Li

Qi Li is a doctoral student in the Department of Sociology and the Institute of Population Research at The Ohio State University. Her research uses quantitative methods to investigate the intersection of family, health, and incarceration, with a particular emphasis on intergenerational ties. Her work has been published in journals such as Social Science Research, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, and Community, Work & Family.

Chris Knoester

Chris Knoester is associate professor of sociology at The Ohio State University. His research has traditionally focused on the effects of children on parents’ lives and on the patterns and implications of fathering, specifically. This paper is an extension of his research on leave-taking that has been published in Social Forces, Journal of Marriage and Family, Sex Roles, Journal of Family Issues, Journal of Social Policy, and Community, Work, & Family.

Richard J. Petts

Richard J. Petts is a professor of sociology at Ball State University. His research focuses on family inequalities, with a specific emphasis on parental leave, father involvement, and workplace flexibility as policies and practices that can reduce gender inequality, promote greater work-family balance, and improve family well-being. He is a member of the International Network on Leave Policies & Research and co-editor of the journal Community, Work & Family, and his work has been featured in numerous media outlets such as The New York Times, CNN, USA Today, and Bloomberg. His website is www.richardpetts.com.

References

- Acker, Joan. 1990. “Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies: A Theory of Gendered Organizations.” Gender & Society 4(2):139–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/089124390004002002.

- Aitken, Zoe, Cameryn C. Garrett, Belinda Hewitt, Louise Keogh, Jane S. Hocking, and Anne M. Kavanagh. 2015. “The Maternal Health Outcomes of Paid Maternity Leave: A Systematic Review.” Social Science & Medicine 130:32–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.001.

- Baum, Charles L., II, and Christopher J. Ruhm. 2016. “The Effects of Paid Family Leave in California on Labor Market Outcomes.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 35(2):333–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21894.

- Bianchi, Suzanne M., John P. Robinson, and Melissa A. Milkie. 2006. Changing Rhythms of American Family Life. New York: Russell Sage.

- Blekesaune, Morton, and Jill Quadagno. 2003. “Public Attitudes toward Welfare State Policies: A Comparative Analysis of 24 Nations.” European Sociological Review 19(5):415–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/19.5.415.

- Bullinger, Lindsey R. 2019. “The Effect of Paid Family Leave on Infant and Parental Health in the United States.” Journal of Health Economics 66:101–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.05.006.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2020. “Employee Benefits in the United States–March 2020.” https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/ebs2.pdf.

- Bygren, Magnus, and Ann-Zofie Duvander. 2006. “Parents’ Workplace Situation and Fathers’ Parental Leave Use.” Journal of Marriage and Family 68(2):363–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00258.x.

- Byker, Tanya S. 2016. “Paid Parental Leave Laws in the United States: Does Short-Duration Leave Affect Women’s Labor-force Attachment?” American Economic Review 106(5):242–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20161118.

- Cherlin, Andrew J. 2014. Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-Class Family in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Chung, Heejung, and Bart Meuleman. 2017. “European Parents’ Attitudes toward Public Childcare Provision: The Role of Current Provisions, Interests and Ideologies.” European Societies 19(1):49–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2016.1235218.

- Cotter, David, Joan M. Hermsen, and Reeve Vanneman. 2011. “The End of the Gender Revolution? Gender Role Attitudes from 1977 to 2008.” American Journal of Sociology 117(1):259–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/658853.

- Cramer, Katherine J. 2016. The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- England, Paula. 2010. “The Gender Revolution: Uneven and Stalled.” Gender & Society 24(2):149–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243210361475.

- Gardner, Akayla. 2021. “Pandemic Drives Business Support for Paid Leave, Study Finds.” Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-26/covid-19-pandemic-drives-up-support-for-u-s-national-paid-leave.

- Gault, Barbara, Heidi Hartmann, Ariane Hegewisch, Jessica Milli, and Lindsey R. Cruse. 2014. “Paid Parental Leave in the United States: What the Data Tell Us about Access, Usage, and Economic and Health Benefits.” Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/B334-Paid-Parental-Leave-in-the-United-States.pdf.

- Gilens, Martin, and Benjamin I. Page. 2014. “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens.” Perspectives on Politics 12(3):564–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592714001595.

- Glynn, Sarah J. 2016. Breadwinning Mothers are Increasingly the U.S. Norm. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2016/12/19/295203/breadwinning-mothers-are-increasingly-the-u-s-norm//.

- Grunow, Daniela, Katia Begall, and Sandra Buchler. 2018. “Gender Ideologies in Europe: A Multidimensional Framework.” Journal of Marriage and Family 80(1):42–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12453.

- Hamad, Rita, Sepideh Modrek, and Justin S. White. 2019. “Paid Family Leave Effects on Breastfeeding: A Quasi-Experimental Study of U.S. Policies.” American Journal of Public Health 109(1):164–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304693.

- Han, Wen-Jui, Christopher Ruhm, and Jane Waldfogel. 2009. “Parental Leave Policies and Parents’ Employment and Leave-Taking.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 28(1):29–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20398.

- Han, Wen-Jui, and Jane Waldfogel. 2003. “The Impact of Recent Legislation on Parents’ Leave Taking.” Demography 40(1):191–200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2003.0003.

- Harrington, Brad, Fred V. Deusen, Jennifer S. Fraone, Samantha Eddy, and Linda Haas. 2014. The New Dad: Take Your Leave. Boston: Boston College Center for Work and Family. (https://www.fatherly.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/BCCWF20The20New20Dad20201420FINAL.pdf).

- Hays, Sharon. 1996. The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Heymann, Jody, and Kristen McNeill. 2013. Children’s Chances: How Countries Can Move from Surviving to Thriving. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Hochschild, Arlie, and Anne Machung. 1989. The Second Shift: Working Parents and the Revolution at Home. New York: Viking.

- Huang, Rui, and Muzhe Yang. 2015. “Paid Maternity Leave and Breastfeeding Practice before and after California’s Implementation of the Nation’s First Paid Family Leave Program.” Economics and Human Biology 16:45–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2013.12.009.

- Jacobs, Jerry A. and Kathleen Gerson. 2004. The Time Divide: Work, Family, and Gender Inequality (The Family and Public Policy). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Klerman, Jacob A., Kelly Daley, and Alyssa Pozniak. 2012. “Family and Medical Leave in 2012: Technical Report.” Cambridge, MA: Abt Associates Inc. Retrieved June 1, 2020 (https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/legacy/files/FMLA-2012-Technical-Report.pdf).

- Knijn, Trudie, and van Oorschot, Wim. 2008. “The Need for and the Societal Legitimacy of Social Investments in Children and Their Families: Critical Reflections on the Dutch Case.“ Journal of Family Issues 29(11):1520–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X08319477.

- Knoester, Chris and Qi Li. 2021. “Preferences for Paid Paternity Leave Availability, Lengths of Leave Offerings, and Government Funding of Paternity Leaves in the United States.” Sociological Perspectives. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/07311214211001892.

- Knoester, Chris, Qi Li, and Richard J. Petts. 2021. “Attitudes about Paid Parental Leave: Cross-National Comparisons and the Significance of Gendered Expectations, Family Strains, and Extant Leave Offerings.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 62(3):181–202. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00207152211026705.

- Knoester, Chris, Richard J. Petts, and Brianne Pragg. 2019. “Paternity Leave-Taking and Father Involvement among Socioeconomically Disadvantaged U.S. Fathers.” Sex Roles 81(5–6):257–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0994-5.

- Koslowski, Alison, Sonja Blum, Ivana Dobrotić, Gayle Kaufman, and Peter Moss. 2020. “16th International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research 2020.” (https://ub-deposit.fernuni-hagen.de/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/mir_derivate_00002067/Koslowski_et_al_Leave_Policies_2020.pdf).

- Lewin-Epstein, Noah, Haya Stier, Michael Braun, and Bettina Langfeldt. 2000. “Family Policy and Public Attitudes in Germany and Israel.” European Sociological Review 16(4):385–401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/16.4.385.

- Li, Qi, Chris Knoester, and Richard Petts. 2021. “Cross-National Attitudes about Paid Parental Leave Offerings for Fathers.” Social Science Research 96:102540. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2021.102540.

- Mercer. 2019. The Pressure Is on to Modernize Time-off Benefits: 6 Survey Findings. New York: Mercer. (https://www.mercer.us/our-thinking/healthcare/the-pressure-is-on-to-modernize-time-off-benefits-6-survey-findings.html).

- Milkman, Ruth, and Eileen Appelbaum. 2013. Unfinished Business: Paid Family Leave in California and the Future of U.S. Work-Family Policy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Milkman, Ruth. 2009. “Class Disparities, Market Fundamentalism and Work-Family Policy: Lessons from California.” Pp. 339–64 in Gender Equality: Transforming Family Divisions of Labor (The Real Utopia Project Volume VI), edited by J. G. Gornick and Marcia K. Meyers. New York: Verso,

- Mischke, Monika. 2014. Public Attitudes Towards Family Policies in Europe. Linking Institutional Context and Public Opinion. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer VS.

- Nepomnyaschy, Lenna, and Jane Waldfogel. 2007. “Paternity Leave and Fathers’ Involvement with Their Young Children: Evidence from the American Ecls-B.” Community, Work & Family 10(4):427–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800701575077.

- Newman, Joshua I. and Michael D. Giardina. 2011. Sport, Spectacle, and NASCAR Nation: Consumption and the Cultural Politics of Neoliberalism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Page, Benjamin I., Larry M. Bartels, and Jason Seawright. 2013. “Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealth Americans.” Perspectives on Politics 11(1):51–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S153759271200360X.

- Peck, Jamie. 2010. Constructions of Neoliberal Reason. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Petts, Richard J., and Chris Knoester. 2018. “Paternity Leave-Taking and Father Engagement.” Journal of Marriage and Family 80(5):1144–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12494.

- Petts, Richard J., and Chris Knoester. 2019. “Are Parental Relationships Improved if Fathers Take Time off of Work after the Birth of a Child?” Social Forces 98 (3):1223–56.

- Petts, Richard J., and Chris Knoester. 2020. “Are Parental Relationships Improved if Fathers Take Time off of Work after the Birth of a Child?” Social Forces 98 (3):1223–56.

- Petts, Richard J., Chris Knoester, and Qi Li. 2020. “Paid Paternity Leave-Taking in the United States.” Community, Work & Family 23(2):162–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2018.1471589.

- Petts, Richard J., Daniel L. Carlson, and Chris Knoester. 2020. “If I [Take] Leave, Will You Stay? Paternity Leave and Relationship Stability.” Journal of Social Policy 49(4):829–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279419000928.

- Pew Research Center. 2017. Access to Paid Family Leave Varies Widely across Employers. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/03/23/access-to-paid-family-leave-varies-widely-across-employers-industries/.

- Pew Research Center. 2018. About One-Third of U.S. Children are Living with an Unmarried Parent. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/27/about-one-third-of-u-s-children-are-living-with-an-unmarried-parent/.

- Pew Research Center. 2019. 8 Facts about American Dads. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/12/fathers-day-facts/.

- Pfau-Effinger, Birgit. 2005. “Culture and Welfare State Policies: Reflections on a Complex Interrelation.” Journal of Social Policy 34(1):3–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279404008232.