?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Emerging from a confluence of events – including Black Lives Matter Movement (BLM) – racial consciousness has intensified in recent years. In the wake of a long declining labor movement, there has also been a surprising upsurge in labor militancy. Are these two currents systematically related? Situating our analysis in the sociological literature on social movement spillover, we ask if there is evidence of racial justice spillover into and stimulating workplace militancy. Employing all known strikes and worker protests during 2021 and 2022, we find: (a) racial justice demands did, indeed, appear as part of workplace militancy during this period; (b) racial justice demands were voiced in both worker protests and strikes launched most heavily by unions but also by alt-labor/SMOs and by unorganized workers; (c) weekly time-series regression models indicate that BLM demonstrations stimulated the frequency of workplace protests and strikes with racial justice demands which, in turn, stimulated wider worker militancy over other issues; and (d) interdependency analysis of worker actions reveals that unionized worker protests served as a key catalyst driving other forms of worker militancy with racial justice demands. We discuss the implications of our findings for social movement spillover theory and for moving racial justice and labor movements forward.

“Black workers have historically been the backbone of this country, its institutions, and innovations. Therefore, it is fully within our rights and dignity that we be treated and compensated fairly. Just as we have the right to live, we also have the right to work.”

--Patrisse Cullors, Black Lives Matter (BLM) Co-founder and past Executive Director of BLM Global Network Foundation.

“Freedom means economic freedom.”

--Angela Angel, BLM Global Senior Advisor

“I think it’s a historic moment, a new level of intersection between our fights. The labor movement is owning that until Black communities can thrive, none of us can thrive.”

--Mary Kay Henry, President, Service Employees International Union (SEIU).

Introduction

In recent years, we have seen Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests help inspire and directly support a union organization drive at an Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, launched in March 2021. In a facility with approximately 80 percent Black workers, key issues coupled demands for worker dignity and respect with union recognition. The first successful union formation at Amazon – the Amazon Labor Union (ALU) – took place at the Staten Island warehouse (JFK8) led by Christian Smalls, Derrick Palmer, Angelika Maldonado, among others in a warehouse comprised largely Black and Latinx employees. Workers Assembly Against Racism (WAAR) assisted the effort by signing up workers and placing pro-union art in key locations. Between May 2021 and February 2022, WAAR mobilized other activists (students, migrant workers, BLM members, housing, unionists) in support of ALU (Murphy Citation2022). Elsewhere, the Philadelphia Labor for Black Lives Coalition led a general protest for racial justice at work on May 25, 2021. AFL-CIO’s hierarchy has called for racial solidarity at work, helped unions drive the “Strike for Black Lives” campaign in July 2020, and sponsored “Black Labor Week” in September 2020. These actions and others have prompted some in the labor press to proclaim that a new vibrancy was being breathed into workplaces and unions by BLM (Elk Citation2018) and that the spirit of BLM and the George Floyd uprising persists in and continues to move the current labor movement. Some have hailed unions as significant supporters of the BLM movement (Green Citation2020), while others see organized labor’s efforts falling short (Elk Citation2020).

Is there a systematic relationship between demands for racial justice and the new labor militancy?Footnote1 In other words, has the Black Lives Matter/Movement for Black LivesFootnote2 started to attain its universalist social justice potential by moving into the workplace? We focus on the intersection of three key social-historical currents: heightened racial consciousness driven primarily by the BLM Movement, innovative forms of labor organizing, and recent surge in labor militancy.

The BLM movement began as a hashtag online movement in the wake of the 2013 acquittal of George Zimmerman in the murder trial of Trayvon Martin. BLM acquired international status in 2014, when the movement took to the streets in response to Michael Brown’s murder by a former police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. Since that point, key BLM activists – including Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, Opal Tomati – have created an international coalition of more than 50 organizations and thousands of participants who constitute the Movement for Black Lives (Ray Citation2020), becoming a universal rally cry for racial justice. The BLM niche space is defined, in part, by activists who are disproportionately Black, Latinx, female, and young (Heany Citation2022). Key tenets of the movement’s political philosophy are grounded in radical Black feminist pragmatism (Woodly Citation2022). As the most recent historical phase of the Black Liberation struggle, BLM features an emphasis on intersectionality unseen in earlier movements (Heany Citation2022).

BLM’s foci and agenda are much broader than racist police brutality. It is about nothing less than the systematic structuring and embedding of racism into the institutional arrangements and cultural fabrics of American life – the ways that Black lives are devalued or do not matter to principle social institutions including the police, criminal justice system, schools, health care, financial systems, and workplaces. BLM vision and goals highlight the significance of economic justice (https://m4bl.org/policy-platforms/economic-justice) and the AFL-CIO has called for unions to be “partners, allies, and fellow community members” with the BLM movement (AFL-CIO Citation2015; Larson Citation2016).

In general, demands for racial justice in the US have been given new life by a confluence of recent contentious eventful developments. On the one hand, the Black Lives Matter movement (e.g., Woodly Citation2022) along with calls for a Third Reconstruction (Barber and Wilson-Hartgrove Citation2016, Joseph Citation2022) and, on the other hand, reactionary white supremacist counter-movements, racist political rhetoric and actions flowing from the Trump administration and reactionary relatives, and continuing history of police violence against Black citizens (including the vicious and highly publicized murder of George Floyd and corresponding uprising in 2020) have all fueled a heightened sense of racial consciousness.

Predicated on weaknesses associated with traditional labor unions, innovative forms of labor organizing have also developed in recent years. Some activists and scholars (e.g., Rolf Citation2016, Rosenblum Citation2017) have argued that unions have declined and become ineffective because they are outmoded, conservative, too narrowly confined to the collective bargaining model and unable to reach many workers in the contemporary labor market. Alternative worker formations taking the shape of labor-community coalitions, worker-based racial civil rights groups, immigrant community-based worker organizations, and faith-based worker rights organizations – also known as worker centers and alt-labor formations – have emerged to ostensibly fill the void in fissured workplaces with unregular workers facing precarious conditions (e.g., Fine Citation2006, Ashby Citation2018, Juravich Citation2018, Cunningham-Cook Citation2021).

With the 2018–19 wave of teacher’s strikes further fueled by the pandemic, labor militancy has surged in surprising ways against the backdrop of long declining trend in strike activity and union formation. Worker militancy has continued to grow since the teacher’s strike wave (Kochan et al. Citation2023) and scholars are pointing to a new labor activism (Cornfield Citation2023). For instance, between 2021 and 2022 the total number of work stoppages increased by 52 percent and the number of workers involved increased by 60 percent (Kallas, Ritchie, and Friedman Citation2023). According to Gallup survey data, public opinion favoring labor unions has increased about 19 percent over the last decade hitting 71 percent approval in 2022, the highest favorability level since 1965, the peak of the civil rights movement (McCarthy Citation2022; Isaac Citation2023).

Building on social movement spillover scholarship (e.g., Meyer and Whittier Citation1994, Isaac and Christiansen Citation2002, Isaac, McDonald, and Lukasik Citation2006), we ask several interrelated questions. First, have demands for racial justice percolating in the wider social environment, notably by BLM’s production of critical discourse (e.g., Dunivin et al. Citation2022) and dual cultural performance (Alexander Citation2017), spilled over into workplaces and animated worker militancy? What evidence is there, beyond the anecdotal, that racial justice forces are stimulating worker militancy in recent years? If racial justice is part of the new worker militancy, where and to what extent has this been occurring? Second, how have workers voiced racial justice demands? That is, what labor organization and contentious collective action vehicles have been deployed? Third, have BLM demonstrations played a systematic spillover role in driving the new workplace militancy? Finally, how, if at all, have these organizational and collective action forms stimulated action in other forms within this wave? That is, what, if any, dynamic interdependencies appear to be driving contentious events initiated by workers? Our analysis should be understood as a first attempt designed to make contributions to: (a) understanding the prevalence and distribution of racial justice in the workplace in recent years; (b) social movement spillover theory conjoining events from BLM and labor movement actions; and (c) the relative role of alt-labor forms of labor organizing in contrast to unions in explicitly fighting for racial justice as a part of the current workers’ rights movement.

Social Movement Spillover Theory

Raising questions about the emergence of racial justice demands in workplace contentious actions lead directly into social movement spillover theory. This body of theory moves away from a singular “movement centric” perspective (McAdam Citation1995) to a more fluid field view with a plurality of movements that have the potential for shaping each other at any given historical moment. Analytic focus typically examines the potential for the development of inter-movement relations and diffusion from one movement with the potential for shaping another movement. Our focus is on spillovers from BLM to workplace militancy.

Scholars have identified a variety of inter-movement dynamics. One form of relationship focuses on contemporaneous bleeding into or spillover between two ascendant (or expanding) movements. Meyer and Whittier’s (Citation1994) study of diffusion of frames, organizational forms, and tactics from the women’s movement into the peace movement during the 1960s and 1970s is a prime example of basic spillover processes between ascendant movements. A second form of inter-movement relation highlights the temporal sequencing of movements where one mass movement serves as a major driver or “initiator” spawning subsequent “spin-off” movements (McAdam Citation1995). Building on union revitalization literature (e.g., Voss and Sherman Citation2000), a third variant of spillover identified by Isaac and Christiansen (Citation2002) focuses on the potential of an ascendant movement to revitalize or rejuvenate the militancy of an older, less dynamic, and perhaps partially institutionalized movement. Isaac and Christiansen analyzed the spillover revitalization of labor movement militancy due to diffusion dynamics stemming from the civil rights and Black liberation movements of the 1960s and early 1970s. This model was extended theoretically and empirically by Isaac, McDonald, and Lukasik (Citation2006) to address a family of ascendant movements generating a radical flank effect (New Left movements of the 1960s and 1970s) in reshaping the older labor movement by driving unionization primarily in public sector workplaces. The systematic evidence produced by Isaac and colleagues, along with historical case studies, shows that these anti-racist struggles did variously merge with, penetrate, and stimulate labor militancy, strike activity, and unionization in important but historically contingent ways.

The internal dynamics of these forms of inter-movement relations depend on diffusion processes; that is, the spread of demonstration effects, movement ideas, discursive frames, artistic productions, behaviors, strategies, tactics, and organizational forms (e.g., Isaac Citation2008, Givan, Roberts, and Sarah Citation2010, Soule and Roggeband Citation2019). This sort of diffusion can flow through a variety of mechanisms or channels connecting one movement to another (Meyer and Whittier Citation1994, Isaac and Christiansen Citation2002) such as: (a) Cultural environment—social-political environment and mass culture such as various forms of media; examples would include the emergence of the #BLM movement and M4BL, politics of the Third Reconstruction, police killings of Black citizens including George Floyd and subsequent uprising; (b) Formal organizational channels—social movement organization relations and coalitions; examples include the Philadelphia Labor for Black Lives Coalition; Voces de la Frontera (https://vdlf.org); Day without Immigrants (https://www.california-mexicenter.org); and AFL-CIO’s supports for BLM and push for a racial justice climate in its unions (AFL-CIO website); (c) Informal channels—overlapping movement communities such as “Stop Cop City, Atlanta” (https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/the fight-against-cop-city); and (d) Direct personal contacts—direct relational contacts or overlapping personnel, that is, activists with a foot in each of two movement cultures such as James M. Lawson, Jr., Angela Davis, and Chris Smalls. In general, we believe that racial justice consciousness has been diffusing into workplaces, amplifying worker voice for workplace racial justice among other demands playing an important role in the current upsurge in labor militancy.

Organizational Mechanisms: Unions and the Rise of Alt-Labor Organizations

Over recent decades, new forms of worker organization have emerged in the midst of the assault on and decline in union formation. These worker centers or “alt-labor” organizations have similar goals but different structures and methods in contrast to traditional labor unions (Fine Citation2005, Citation2006). The core of the current alt-labor movement consists of some 200 to 300 worker centers spread across the country (Ashby Citation2018). Advocates for the rights of marginalized, low-wage workers, alt-labor formations have taken the shape of (a) labor-community coalitions, (b) worker-based civil rights organizations, (c) immigrant-community-based workers’ organizations, (d) faith-based worker rights organizations, and (e) extensions of labor unions like Fight for $15.

Much of the literature focusing on alt-labor is premised on the recognition that a growing segment of the U.S. workforce is difficult, if not impossible, for traditional labor organizing approaches to reach. Expanding irregularity and precarity in positions like “independent contractors” (for fare drivers) that comprise the neoliberal “gig economy” with “fissured workplaces” (Juravich Citation2018) are not able to benefit directly from current labor law and union organizing (see Johnston Citation2018 on NYC taxi drivers), and racialization at work is integrally related to these conditions. Race-based disparities in wages and occupational attainment are well documented, and sociologists also know that precarious, dangerous, and social reproduction work has disproportionately been placed on workers of color. During the pandemic, Black workers (essential and in-person) were more likely to experience safety concerns on the job than white workers (Hammonds and Kerrissey Citation2022), and people of color were much more likely to die on the job, according to a recent AFL-CIO report (Citation2023). In general, workplaces with heavier concentrations of Black employees tend to experience lower quality work environments such as the quality of management culture and work–life balance (Zhang Citation2023).

Questions tend to focus on the role of alt-labor organizations relative to labor unions (Juravich Citation2018) and whether unions and alt-labor can work in tandem as allies in strengthening the workers’ rights movement, including racial justice at work. The juxtaposition of union and alt-labor formations raises interesting and important questions as well as opportunities for novel research on racial justice and inter-movement relations. For example, what has the relative role of alt-labor versus unions been in advocating for racial justice during the recent upsurge? To our knowledge, there is no systematic research on this question. However, there are two important conditions that might give the edge to alt-labor groups. First, alt-labor-type organizations are not institutionally embedded in the conventional collective bargaining apparatus as are unions, so they might have greater freedom to advocate and protest for racial justice. Second, some alt-labor groups are organized by and located within worker of color communities (Cunningham-Cook Citation2021). In combination, it seems reasonable to expect that contentious actions such as protests and strikes with racial justice demands would be more frequently articulated by alt-labor mobilizations than by labor unions. With that said, it is possible that the resource advantages of unions ultimately make them more effective in stimulating action for racial justice. We now turn to an outline of our hypotheses.

Hypotheses

Primarily an online movement in its initial phase, #Black Lives Matter (BLM) emerged in July 2013 in response to the shock wave created by the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the murder of Travon Martin. The character of the movement changed with the Ferguson events in October 2014 as the movement became more engaged in street mobilizations, gaining a dual axis of performativity (Alexander Citation2017). Since the first demonstration for Eric Garner on 19 July 2014, the record indicates more than 6,800 BLM demonstrations in the U.S. alone (Elephrame Citation2023). Given the frequency, breadth, and intensity of BLM demonstrations, we suspect the movement’s racial justice culture has spilled over and diffused into workplaces with increasing demands for racial justice at work. This logic leads to our first core hypothesis:

H1:

(BLM impact on workplace racial justice militancy hypothesis): The frequency of BLM demonstrations has served as a catalyst, at least in part, for workplace racial justice militancy.

Given the growing intensity of racial consciousness in recent years, there is reason to believe that worker actions voicing racial justice grievances might be serving as a catalyst for broader workplace militancy. Perhaps parallel to the militancy spillover from the civil rights and Black liberation movements into workplaces during the 1960s and early 1970s (Isaac and Christiansen Citation2002), contemporary racial justice actions could be stimulating other workplace grievances too (Maffea Citation2022). This reasoning leads to our second hypothesis.

H2:

(Racial justice demands as catalyst for wider workplace militancy hypothesis): Contentious collective actions carrying racial justice demands served, at least in part, as a stimulus for more general worker militancy.

Prior to, during, and since the peak pandemic years, analysts and other observers have been referring to worker actions with terms like militancy “upsurge” and “wave” (Furman and Winant Citation2021, Isaac Citation2023, Kochan et al. Citation2023, Sallaz and Trongone Citation2023, Vallas and Johnston Citation2023). Social movement scholars conceptualize movement waves as periods of extensive and intensive protest activity involving multiple mass collectivities that are often diffused across a sizable spatial territory (e.g., Traugott Citation1995, Almeida Citation2008). Likewise, when workers strike in increasingly large numbers and do so across multiple industries and regional locations, we speak of “strike waves,” which have occurred with some frequency and importance in the U.S. since the late nineteenth century (Brenner Citation2009).

Instances of collective contention are not independent events but rather are linked with prior events and then shape subsequent events in various ways. Indeed, one of the most fundamental features of collective action is its inter-connectedness which can become especially intense during waves of contention (Koopmans Citation2007). A major question in the study of protest or strike waves focuses on dynamics internal to the wave that drives the replication of actions. Here, we are interested in contentious actions voicing racial justice and their replication and their diffusion through mechanisms of worker organization and collective action. In other words, we focus on the dynamic inter-connectedness between forms of worker organization (union and alt-labor) and collective action (protests and strikes).

Much of the research on protest waves tends to feature a specific type of protest form such as civil rights sit-ins or Freedom Rides. However, contentious action waves are frequently constituted by heterogeneous forms of collective action (e.g., Tarrow Citation1995 for the mass protest wave in 1960s-1970s Italy; Isaac, McDonald, and Lukasik Citation2006 for new left protests during the 1960s-1970s U.S.). Even strike waves can consist of more than one form of strike (e.g., contract negotiation strike, sit-down strike, sympathy strike, general strike). The organizational forms that launch collective actions can vary too. In the current period, the contrast between unions and alt-labor organizations is an important part of the organizational infrastructure in the contentious mix.

We suspect that protests, more than strikes, have been playing a role as dynamic catalyst in racial justice demands because protests are not coupled to the collective bargaining process as are strikes, nor do they commit workers to possibly long and costly battles like strikes. They can be mobilized and demobilized in relatively short order, often within a day’s duration. But what about the organizational form mobilizing protests?

Because of their resource and power advantage (i.e., relative size, monetary resources, organizational infrastructure, work site connectivity) as well as visibility, unions are most likely to play a key role as dynamic catalyst driving other forms of mobilized collective contention advocating for racial justice. Sometimes worker protest will be linked to a strike at the same site (e.g., Brookline, MA teacher’s union (NEA) who held a protest rally after a strike vote and launched a strike three days later). In other cases, a protest by workers in one site may motivate workers to strike in a different workplace. This is the theoretical foundation for our third hypothesis, which points to the flexibility of the protest form deployed by relatively resource-advantaged unions.Footnote3

H3:

(Dynamics of internal militancy wave mechanisms hypothesis): Union mobilization of protests (more than strikes) has played a greater role than alt-labor (or non-organized workers) in stimulating action for racial justice inside this wave of labor militancy.

By analyzing the relations between collective actions voicing racial justice issued through various mechanisms, we can map the structure of interdependencies (signaling diffusion) across heterogeneous collective actors within this movement wave.

Data and Measures

Testing our hypotheses requires data for BLM Movement actions, forms of labor organization, and labor militancy.

Black Lives Matter Movement

BLM demonstrations began in 2014 with events in Ferguson and, prior to the George Floyd murder, fluctuated annually between 172 (2019) and 794 (2016) averaging 387 per year. During 2020, prior to the Floyd murder, there were only 22 demonstrations; after May 25th (day of the murder) to the end of 2020, demonstrations exploded to approximately 3,672 events. BLM demonstrations continued but at a much lower rate during 2021 (n = 134) and 2022 (n = 142) (Elephrame Citation2023). Although the protest frequency was much lower than the 2020 surge, evidence suggests that the discursive impact (e.g., illuminating forms of “systematic racism”) of BLM protest has legs, that is, it has been sustained beyond protest peaks (Dunivin et al. Citation2022), movement sentiment and infrastructure has not evaporated (Abrams Citation2023). Sustained BLM influence may register in workplaces as well.

Our measure of BLM intensity relies on the Elephrame database which records all known BLM demonstrations, defined as “any public display that is centered on communicating the value of a Black individual or Black people as a whole that occurred in the United States after the first demonstration for Eric Garner on 7/19/2014” (Elephrame Citation2023). For the years 2021–2022, the database shows 276 BLM demonstrations, 262 of which took place in the U.S. We restrict our BLM measure to those events that took place in the U.S.Footnote4

Workplace Militancy

To gauge workplace militancy, we employ data on all known worker strikes and worker protests for calendar years 2021 and 2022 collected by the Cornell University ILR Labor Action Tracker Project (Cornell University Citation2023).Footnote5 Strikes and protests are distinguished by cessation of production; strikes stop production for some period of time, while protests do not. These are high-quality data reporting strikes of all sizes and worker protests that do not involve the cessation of production, far superior in coverage to exclusive BLS data which do not report worker protests and only report strikes that cross the threshold of at least 1,000 strikers.Footnote6 We also examine organizational forms in a three-fold typology (unions, alt-labor, no organizational sponsor) used to launch strikes and protests carrying racial justice demands. There were also a few events launched by non-labor social movement organizations such as the New Jersey NOW chapter which we include in the alt-labor category because they are all advocacy organizations without the collective bargaining power of unions.

Worker demands are defined by the project as the “main demands associated with an event.” The 12 major categories used to organize the data include: (1) $15 minimum wage; (2) COVID-19 protocols; (3) first contract; (4) health and safety; (5) health-care benefits; (6) job security; (7) pandemic relief; (8) pay; (9) retirement benefits; (10) staffing; (11) union recognition; and (12) racial justice. These are the most common demands but not an exhaustive list. Other less frequent demands might be part of a demand set for a contentious event but are not part of the filtering algorithm on the project website (e.g., grievances against sexual harassment). Further details about the project methodology can be found at the ILR website.

We organize the BLM and labor militancy data in the weekly time domain. Our opening unit of analysis appears with the week of 12/27/2020–1/2/2021, and we close with the last week of 2022 which yields a T = 105 weekly observations. Descriptive statistics for all event variables are presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for weekly event variables, 2021–2022.

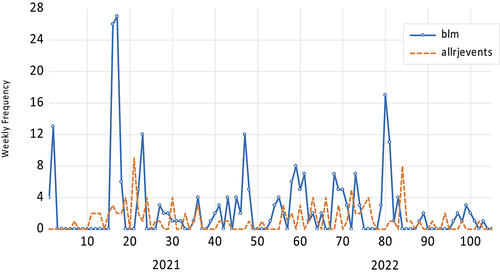

While unusual in sociology, analysis of weekly time-series observations has advantages over more common annual temporal units of analysis. For instance, they are more fine-grained, reduce temporal aggregation bias and permit a closer assessment of potential fast-moving causality among contentious collective actions of interest. They also tend to be less smooth than annual series, resulting in a lower likelihood of time trend-based serial correlation. The weekly series for BLM demonstrations and all labor actions (strikes + protests) with a demand for racial justice are shown in .

Analytic Methods

We focus on both descriptive and inferential assessments to evaluate our major hypotheses. Tests of hypotheses 1–3 draw upon inferential insights gauged from time-series event regression models for percentage change and count variables. OLS is employed for the former. For the count data, we start with the Poisson estimator. Because the restrictive assumption of conditional variance and mean equivalence is likely to be violated in such data, we evaluate the possible presence of significant overdispersion (conditional variance > conditional mean) with the Wooldridge test. If overdispersion is substantial and ignored, standard errors and t-tests will be biased. In such instances, we estimate the magnitude of the overdispersion factor and use it to re-estimate the model with the less restrictive quasi-maximum likelihood negative binomial estimator. We gauge potential problematic serial correlation in the errors of our models with the Ljung-Box Q test.

Because hypothesis 3 attempts to assess the combinational form of worker organization (union, alt-labor, no organization) and collective action (strike, protest) that is most responsible for driving other forms of worker racial justice action inside the militancy wave, questions of exogeneity are central to the specification and estimation process. Therefore, we examine Granger exogeneity tests for these dynamic processes prior to estimating the Poisson or negative binomial regression models. The Granger tests are symmetric distributed lag regression analyses that take the following two equation form for any pair of time-series variates:

The symmetric structure of this specification enables an assessment of whether x or y is likely an exogenous driver of the other, evidence of mutual determination, or a null relationship moving in both directions. The null hypothesis for x → y and y → x is evaluated with Wald F tests for the cumulative distributed lags for x and y in Equationequations (1)(1)

(1) and (Equation2

(2)

(2) ) above (Cromwell et al. Citation1994).

Analysis and Findings

Racial Justice Spillover

The number of sites that incurred strikes and protests for any worker demands over this two-year period totaled 1,031 and 1,224, respectively. Approximately 5 percent of each figure (55 strikes and 56 protests) involved racial justice as part of its demand profile. Both strikes and protests tended to be centered most heavily in various service and transportation/warehousing industries. The industrial sectors with multiple racial justice strike demand events include (in descending order): information, accommodations and food services, education, transportation and warehousing, health care and social assistance, art and entertainment, retail trade; manufacturing, public administration, professional, and other services all had one event each. Industries with multiple racial justice protests included (in descending order): education, accommodations and food services, health care and social assistance, transportation and warehousing, information, other services; waste management, construction, manufacturing, professional, and utilities had one event each. reports the industrial-sector distribution of these events.

Table 2. Industry location of strikes and protests with racial justice as part of demands.

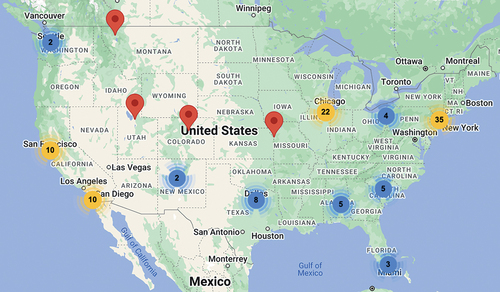

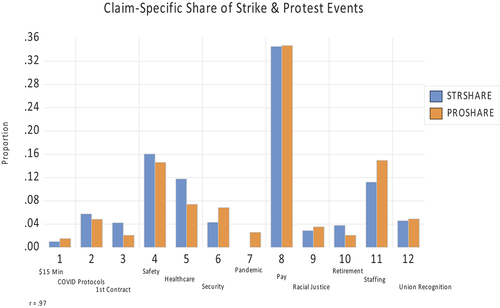

shows the geographic distribution of all strikes and protests calling for racial justice. While high population centers have a greater frequency of contentious events (e.g., New York City, Chicago, West Coast) than others, these actions have occurred to some extent in every major region of the nation over the period. The proportionate claim-specific share by strike and protest events is shown in . For comparison, events containing racial justice demands are small relative to demands for pay increases, but they are approximately equivalent in share to other important workplace grievances, including those calling for first contract negotiations, COVID-19 protocols, job security, retirement benefits, and union recognition. Mobilization by strikes and protests across grievance categories are highly correlated (r = .97).

Figure 2. Geographic distribution of worker contentious collective actions with racial justice demands, 2021–2022.

Figure 3. Claim-specific share by strike and protest events, 2021–2022.

Considering these data collectively tells us that racial justice demands have indeed spilled over into workplace collective contention with employers. However, the extent to which this has occurred is perhaps less than one might have expected given demands for racial justice across the U.S. more generally. But what are the organization-collective action mechanisms that have carried these racial justice demands?

Organization-Collective Action Forms and Racial Justice Mobilization

Organization and collective action formations are key vehicles for expressing racial justice grievances in workplaces.Footnote7 Here, we are interested in organization-collective action couplets (e.g., union strikes, alt-labor protests) through which such actions have mobilized. Over our timeframe, we find that racial justice demands have mobilized at 111 locations. Our data indicate that both unions and alt-labor organizations have mobilized collective actions with racial justice demands. The organization-collective action joint distributions are reported in as cell frequencies and percentages of the total number of events (N = 111).

Table 3. Frequency of racial justice events by organization and collective action forms.

There are several notable patterns in . First, unions account for the largest share of racial justice-based events (32 strikes + 29 protests = 61 events for 55 percent of the total). Second, alt-labor organizations are responsible for almost one-third of the total actions, while the unorganized events had a 13 percent share. This suggests a clear organizational hierarchy with union, alt-labor, and no organizational sponsor in descending order. T-tests for pairwise equality across collective action totals (protests + strikes) indicate that the differences between organizational forms (unions, alt-labor, and no organization) are all statistically significant (p < .001). Consistent with their numerical presence, unions have been the most frequent racial justice mobilizers.

BLM Actions and Racial Justice Demands at Work

Our first core hypothesis highlights the short-term frequency of BLM demonstrations as a cross-movement catalyst for racial justice demands at work. Recall that we anticipate that the greater the weekly BLM frequency, the more likely that strikes and protests will make racial justice demands. This sort of diffusion spillover from one movement to another was implicit in the prior descriptive discussion, but here we make it explicit with direct empirical test.

examines the impact of BLM demonstrations at varying lag lengths (from t to t-2) on change in three dependent variables: racial justice protests as a percentage of all worker protests (models 1–3); racial justice strikes as a percentage of all strikes (models 4–6); and all racial justice events as a percentage of all workplace militancy events (models 7–9). The patterns in signal significant BLM spillover into workplace militancy. BLM demonstrations show significant impact on percentage changes in (a) protests (at t and t-1), (b) strikes (t-3), and (c) both protests and strikes combined (t-1 and t-2). BLM demonstrations register influence faster (i.e., shorter time lags) for workplace racial justice protests than strikes which, based on mobilization flexibility, is precisely what one would anticipate.Footnote8

Table 4. OLS regression estimates of BLM demonstration impact on percentage change in racial justice workplace militancy.

We are led to the same inferences when we examine the number (i.e., weekly count) of racial justice events (protests and strikes). Model 1 in presents Poisson results for racial justice event counts as a function of its lagged value, a measure of exposure to racial justice demands appearing in a strike or protest, and the number of BLM demonstrations lagged one week.Footnote9 Because the Wooldridge test signals significant overdispersion, the Poisson estimates of the standard errors could be biased downward, so we re-estimate with a negative binomial model (model 2). The negative binomial results lead to the same inference as the Poisson: BLM demonstrations significantly influence workplace contention with racial justice content. The coefficient in model 2 tells us that, on average, a one percent increase in weekly frequency of BLM demonstrations is associated with a 4.8 percent increase in racial justice workplace contention in the subsequent week. In combination, we take this as solid support for hypothesis 1: BLM demonstrations increase the proportion and the frequency of workplace contention (strikes and protests) with racial justice demands. But is this spillover impact confined exclusively to contestation expressing racial justice demands, or did BLM have a wider impact on worker militancy over workplace grievances generally?

Table 5. Regression count models for all racial justice events and all non-racial justice events.

Racial Justice Demand Events As Catalyst for Wider Workplace Militancy

While racial justice demands in workplace collective contention have been proportionately smaller than expected, that does not necessarily mean that these events were unimportant for new worker militancy. They could have had an outsized initiating contagion impact on workplace militancy more widely. Our second hypothesis anticipates that this result – the frequency and timing of racial justice demand events played a role, at least in part, for driving worker collective actions more generally.

To test this possibility, we provide evidence in frequency change regression models 3 and 4 in for the influence of racial justice events (protests + strikes with racial justice demands) on all other contentious workplace events (protests + strikes without racial justice demands) and BLM demonstrations. Recall that the dependent variable is a measure of general workplace militancy excluding events with racial justice demands. Model 3 shows significant overdispersion, so we re-estimated with negative binomial regression presented in model 4.

The negative binomial estimates parallel those of the Poisson; racial justice actions show a statistically significant impact on workplace militancy with all grievances: a one-percent increase in racial justice actions leads, on average, to a 5.4 percent increase in total worker militancy. The overall pattern of results in suggests that BLM demonstrations have a direct impact on racial justice militancy at work and an indirect impact on general workplace militancy via workplace racial justice actions; i.e., BLM actions → Workplace racial justice militancy → Generalized workplace militancy.Footnote10

What about the possibility of reverse causation here? The evidence is much weaker for the prospect of general workplace militancy influencing racial justice demand militancy. A parallel change model shows a positive but weaker and statistically marginal (p > .05) coefficient. We also find null results from Granger exogeneity tests.Footnote11 On balance, we read this evidence to be consistent with the support of hypothesis 2. Racial justice demand events in this context of heightened racial consciousness served as a partial indirect catalyst stimulating general workplace militancy in recent years.

Structure of Racial Justice Organization-Collective Action Dynamics

Our final question centers possible internal mechanisms driving the flow of racial justice actions within the current wave of worker militancy. In other words, we ask if there are systematic interdependencies unfolding among organization-action forms mobilizing racial justice demands. Our third hypothesis anticipates that unions have likely been playing a larger stimulating role than alt-labor organizations; and while unions have engaged in both strikes and protests for racial justice, protest actions have been most efficacious in driving other forms of worker racial justice militancy.

Summary evidence on this question is presented in . Because each organization (union, alt-labor, no organization)-action (strike, protest) form could be endogenous with respect to other collective action forms, it is important for specification purposes to gain some leverage on the possible leading form. We do so by first estimating Granger exogeneity tests on all possibilities over the range of three different lags (15 pairs of variables × 2 directions of influence each × 3 different lags = 90 estimates). Because it would be cumbersome to present so many estimates, shows only relations that were (a) consistently significant in the Granger exogeneity tests and (b) significant in at least one of three possible lags (t-1 through t-3) in the Poisson count models.Footnote12 The only form of organization-collective action to meet the rigors of these tests is union protest.

Table 6. Estimates of interdependencies among racial justice actions by organization and collective action form.

reports four models – union strikes, alt-labor strikes, alt-labor protests, and unorganized protests – all of which contain racial justice demands. Each model shows the result of the Granger test (F-value) indicating that union protests are exogenous relative to the dependent variable of interest. For example, in model 1, Granger tests two possibilities against the null hypothesis:

Union protests → Union strikes (F = 3.17*)

Union strikes → Union protests (F = .32)

This example indicates that union protests are likely a driver of union strikes, but there is no evidence for the reverse impact. Granger tests signal that union protests prove to be a driver for all four other forms of action. The impact of union protests on each form is estimated as a function of a constant and union protests at various lags from 1 to three weeks in duration.Footnote13 The temporal location of significant lags varies, but union protests show evidence of influence for increasing union strikes (.184* + .211**), alt-labor strikes (.201***), alt-labor protests (.237***), and unorganized protests (.146***).

What does this pattern of relations suggest? Unions, more than alt-labor or unsponsored actions, are driving worker racial justice militancy in its various forms, and it is due to protests more than strikes that unions are stimulating these other forms of racial justice mobilization at work within the current wave. Overall, the evidence is consistent with H3.

Summary

Our hypotheses and inferences are summarized in .

Table 7. Summary of Hypotheses and Findings.

First, we do find evidence that concerns about racial justice have spread into workplace collective actions in recent years, even if the relative proportion of racial justice in all demands is smaller than expected. However, because we are working with just a two-year period, it is impossible to tell whether the level of racial justice demands has increased across historical time. Second, while there are reasons to expect that alt-labor organizations might be more active in mobilization for racial justice demands, we find instead that unions were out front in the locational frequency of such demands. Third, we tested the hypothesis that BLM demonstrations were driving, in part, racial justice demands at work (H1) which, in turn, were contributing to more general worker militancy (H2). Evidence does indicate that contentious workplace events pushing for racial justice were stimulated by BLM demonstrations and did indeed serve to stimulate other workplace demands. Finally, we hypothesized that unionized workers using the protest tactic played a key role in driving other forms of workplace racial justice contention (H3) and find support for that argument.

Racial justice articulated in union protests appears to be a major driving force for racial justice demands in other collective action forms, and this impact persists through lags up to three weeks in length. Alt-labor and unorganized workers show influence on each other but take more time to develop and do not appear to have a systematic influence on union protests or strikes for racial justice. In other words, union protests reveal an important initiating force not displayed by other workplace organization-collective action forms in recent years.

Conclusions and Implications

The results of this study derive from the Elephrame BLM database and new data collected by the Cornell University ILR Labor Tracker project. The Labor Tracker provides rich and important data with advantages over exclusive reliance on the BLS. But the Labor Tracker has limitations at this point too. For our study, the short analytic window (two years) impedes our ability to establish stable long-term trends due to the changing presence of racial justice demands in American workplaces. It appears that we are still in the midst of an unfolding militancy upsurge. We also relied on explicit claims by workers for racial justice demands. As important as these data are, we do not know precisely how much racial justice consciousness and moral outrage may be influencing workplace demands that were not explicitly tagged as racial justice claims; that is, racial justice sensibilities could be pushing other worker demands for things like job security, pay, safety, and union formation without always being framed in racial justice terms. However, our findings in support of hypothesis 2 suggest that racial justice demands at work have contributed to stimulating other worker demands.

Our findings are obviously rooted in a short span of history. Moving forward, a longer period of empirical observations will help us determine the level of resilience and potency of racial collective action for workplace militancy and the extent to which BLM continues to be a driving force. Next steps should also pay attention to the extent to which racial militancy and labor militancy are getting translated into unionization gains and precisely where and under what conditions such gains might be appearing. Knowledge of prior union revitalization processes will be helpful. For example, Voss and Sherman (Citation2000) illuminated the importance of three key factors: (1) political crisis in a union local leading to new leadership; (2) the presence of leaders with activist experience acquired outside the labor movement; and (3) top-down influences from the international leadership in favor of innovation. Workplace demographic composition (especially race and age) will also likely matter (e.g., Isaac, McDonald, and Lukasik Citation2006; Cha, Holgate, and Yon Citation2018), a point signaled by some of the most dramatic recent racially based workplace mobilizations (e.g., Amazon-Bessemer, AL., Amazon-Staten Island, Philadelphia Labor for Black Lives Coalition).

Our results derive from not only a limited historical period that may or may not generalize across time (see Isaac and Griffin Citation1989) but also from weekly observations. It would be useful to know if patterns are fractal and reproduce across different elemental time periods (e.g., scaling up to months, quarters, or years). These short elemental time periods or weekly units of analysis are useful for gauging quick change-based relations, but they cannot illuminate slow-moving, long-term changes (e.g., Pierson Citation2003). That will require a different form of historical analytic strategy. Despite these data limitations, our findings have important implications for the potential universality of the Movement 4 Black Lives, for social movement spillover theory, and contemporary dynamics of militancy in the contemporary labor field.

In the context of the Movement 4 Black Lives, the Third Reconstruction, the uprising surrounding the vicious killing of George Floyd in 2020 registered concrete event universality (Mueller Citation2023). Within days, protests erupted across the country and around the world. Understandably, much of the moral outrage and collective anger targeted the state’s law enforcement arm, leading to calls to defund the police and abolition of criminal justice apparatuses, among others. While the ILR data did not exist at the time of the Floyd killing, we have operated on the premise that the force of that event as well as other racial justice events, and M4BL would continue to register, be amplified, and carried forward in BLM action currents, and diffuse into different institutional spaces, including workplaces. In other words, movement-based events have the power to travel through time, across geographical space, and penetrate institutional arenas (Sewell Citation1996, Isaac Citation2008, Wagner-Pacifici Citation2010).

Worker agitation for racial justice is certainly present in the new militancy for all major regions of the nation but, not surprisingly, most heavily concentrated in major population centers. These demands are also most heavily concentrated in service and transportation/warehousing industries. While we cannot say with any certainty that worker racial justice actions have increased in recent years because of the limited time frame, there is some indication that strikes with racial justice demands increased in 2022 over their 2021 level. At this point, the possibility of longer-term trend remains to be seen. Going forward, it is imperative that organized labor takes racial justice and the movement for the Third Reconstruction seriously, if only for self-interested reasons. The major upsurges with labor gains and failures in U.S. history pivoted heavily on the presence of within-class racial solidarity (e.g., Du Bois Citation1935, Zeitlin and Weyher Citation2001, Isaac Citation2023). Moreover, in an era of political polarization fueled in part by racial antipathy, there is important evidence that union membership dampens racial resentment among white workers (Frymer and Grumbach Citation2021).

We have highlighted six different combinatorial forms of worker organization (unions, alt-labor, unorganized) and collective action (strikes and protests). Unions, alt-labor organizations, and to a lesser extent, unorganized workers have all been active in voicing racial justice demands at work. But there are important differences. Unions have been more active than alt-labor groups or unorganized workers. Thus, while alt-labor has been playing an important role in filling gaps left by traditional union organizing, it would be a mistake to write off union’s voice for racial justice.

We illuminated the dynamics within the wave of worker militancy by examining catalysts for interdependent linkages among the different forms of worker organization-action. The big story here is the following: First, for all worker actions (strikes and protests) in aggregate (not specific to worker organizational form or demand profile), strikes appear to be driving the mobilization of protests in general; second, when limited to events giving voice to racial justice, union protests are the major catalyst for other forms of action including union strikes, alt-labor strikes and protests, and unorganized protests. The volume and visibility of union protests outside the collective bargaining apparatus registers by increasing union strike activity but also those less conventional forms of racial justice actions as well. We believe it is the diffusion of a leading demonstration effect displayed by unionized workers that prompts other workers outside of labor unions to act in their own ways, under conditions that they currently face and with the organizational resources at hand.

We extend social movement spillover theory by revealing the textured specificity of spillover processes from an ascendant movement (M4BL) to a relatively declining movement (labor) by (a) highlighting organization-collective action forms as key mechanisms for giving voice to racial justice at work and (b) mapping the sequential inter-dependencies driving the spread of racial justice contentious actions within the wave of worker militancy. These findings tell us that spillover dynamics work through variegated organizational-action forms with layers of linkages driving upsurge within a highly heterogeneous workforce.

Others have argued that unions must expand and deepen commitment to social movement unionism vibrancy and activism in the larger fight for worker rights and social justice. We wholeheartedly agree. While Black worker centers can and have played an important role in bridging union and community campaigns (Cunningham-Cook Citation2021), the fight for workers’ rights with a social justice core cannot be ignored or left solely to alt-labor groups (Juravich Citation2018). Unions are essential for worker rights, a vibrant democracy, and a more equal and humane society. Social justice organizations, including alt-labor groups, and unions need to combine efforts and resources to advance the interests of working-class communities (Davis-Faulkner and Sneiderman Citation2020).

There is a long distance to travel for most unions. But our findings do hold out hope; on the one hand, BLS data tells us that Black workers were responsible for most new union growth from 2021 to 2022 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Citation2023); and on the other hand, our analysis suggests that unionized worker militancy for racial justice has been leading the way during the last two years of the upsurge.Footnote14 The question is, of course, will these patterns continue to grow? We believe the answer to this question will likely pivot on several conditions: (a) workers’ ability to increasingly forge a social movement unionism centered on social justice with racial justice at the core (Isaac Citation2023) but with broad intersectional sensibilities that focus on identity-based variances within the working-class (Lee and Tapia Citation2023); (b) elevating the most vulnerable beginning with the marginally employed lower-tier Black workers hungry for recognition, support, and dignity (Young Citation2023); and (c) the movement’s ability to out maneuver and withstand state, corporate, and media repression (Wingfield Citation2023).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Cornell University-ILR Labor Action Tracker project team for access to their data and special thanks to Johnnie Kallas for assistance. We are also grateful for open access to the Elephrame BLM data source. The authors also thank two anonymous reviewers and the editor for helpful comments. The senior author gratefully acknowledges research support from the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Endowment, College of Arts and Science, Vanderbilt University. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meetings of the Southern Sociological Society, March 2023.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Larry W. Isaac

Larry W. Isaac is the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Endowed Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Political Economy at Vanderbilt University. He is past senior editor of the American Sociological Review, past president of the Southern Sociological Society, and previously held the Mildred & Claude Pepper Distinguished Professor of Sociology endowed chair at Florida State University. He is the award-winning author of numerous articles and known for contributions to (a) labor movement processes, (b) civil rights and Black Liberation Movement, (c) work on literary emergence and dialogical conflict, and (d) historical sociology and social change. His writing has received awards from American Sociological Association sections on Comparative-Historical Sociology, Cultural Sociology, Labor/Labor Movement Sociology (twice), and Communication, Information Technologies, and Media. His work has also been recognized by ASA/NSF Advancement of the Discipline, National Endowment for the Humanities, the Society for the Study of Social Problems, and the Southern Sociological Society. He is currently working on a co-authored book about the Nashville civil rights movement.

Brittney Rose

Brittney Rose holds an MA in sociology from Vanderbilt University and continues her work as a Ph.D. student. Her primary interests are in the political economy of military processes, especially discourse on “collateral damage.”

Notes

1. By militancy, we mean contentious collective action expressing grievances. Here that takes several forms: Black Lives Matter demonstrations, workplace strikes, and workplace protests.

2. We use Black Lives Matter (BLM) Movement and Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) interchangeably.

3. We highlight the “relative” resource advantage of unions in contrast to alt-labor organizations and completely unorganized workers.

4. The Elephrame dataset is online open-source data collected since 2014, curated by Alisa Robinson and others. Data were retrieved and organized by week from https://elephrame.com/textbook/BLM/chart at various points during 2023.

5. The Cornell ILR Labor Action Tracker project is an ongoing online open-source dataset, wherein data collection for strikes began in late 2020 and labor protests in early 2021 (see: Cornell ILR Labor Tracker methodology; https: www.striketracker.ilr.cornell.edu).

6. The contrasting image of labor militancy resulting from the BLS data on only “big strikes” (at least 1,000 strikers) compared to the Cornell ILR data is remarkable, amounting to approximately a 16-fold difference: 2021: BLS = 16; ILR = 270; 2022: BLS = 23; ILR = 413 (For BLS data, see www.bls.gov/Annual Historical Table).

7. Names of the unions and alt-labor organizations involved in mobilizing strikes or protests with racial justice demands during this period are listed in Appendix A and B.

8. BLM effects decay to statistical insignificance in the protest models but take longer to influence strikes becoming more potent with time from t-2 (shown) through t-5 (not shown in table): t-2 = .364**, t-3 = .445**, t-4 = .569***, t-5 = .622***, and decay to insignificance at t-6.

9. Standard estimators for count models, such as Poisson and negative binomial, can have difficulty if there is a substantial number of zeros in the distribution of the dependent variable (Long Citation1997), often contributing to overdispersion (Winkelman Citation2010). In such cases, zeros could result from a different underlying process, a possible source of heterogeneity. In the case of racial justice events (strikes + protests) in models 1 and 2 of , strikes and protests must materialize before they can make racial justice demands. To control for this possibility, we include an explicit “exposure” variable to adjust for this sequential process. In , the adjustment factor is in the denominator of the dependent variable measured as a percentage and models are estimated with OLS instead of the Poisson or negative binomial.

10. BLM influences in the count models are significant only at t-1; they decay to insignificance at t-2.

11. Granger F values for the null hypothesis that all labor militancy events do not cause all worker racial justice events for lags t-1, t-2, and t-3 are: F = .16, .39, and .68, all substantially outside the range of statistical significance.

12. All Granger test results are available on request.

13. All union protest influences decay to insignificance at lags beyond three weeks.

14. We also find marginally significant (p = .07) influences of BLM demonstrations and workplace racial justice events in stimulating change in levels of union recognition protests and strikes.

References

- Abrams, Benjamin. 2023. The Rise of the Masses. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- AFL-CIO. 2015. “Labor Commission on Racial and Economic Justice. “BLM and the Labor Movement: Where and How they are the Same.” (https://racial-justice.aflcio.org).

- AFL-CIO. 2023. “Death on the Job: The Toll of Neglect, 2023.” Report/Workplace Health and Safety (https://aflcio.org/reports/death-job-toll-neglect-2023).

- Alexander, Jeffrey. 2017. “Seizing the Stage: Mao, MLK, and Black Lives Matter.” The Drama Review 61(1):14–42.

- Almeida, P.D. 2008. Waves of Protest. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Ashby, S.K. 2018. “‘Traditional’ Labor and ‘Alt’ Labor: Comparisons, Critiques, and Perspectives.” Labor Studies Journal 43(2):101–03. doi:10.1177/0160449X18763440

- Barber, W.J. II and Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove. 2016. The Third Reconstruction: Moral Mondays, Fusion Politics, and the Rise of a New Justice Movement. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Brenner, Aaron. 2009. “Strike Waves.” Pp. 175–76 in The Encyclopedia of Strikes in American History, edited by Aaron Brenner, Banjamin Day, and Immanuel Ness. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Cha, J.M., Jane Holgate, and Karel Yon. 2018. “Emergent Cultures of Activism: Young People and the Building of Alliances Between Unions and Other Social Movements.” Work and Occupations 45(4):451–74. doi:10.1177/0730888418785977

- Cornell University. 2023. ILR School Labor Action Tracker. (https://striketracker.ilr.cornell.edu).

- Cornfield, D.B. 2023. “The New Labor Activism, a New Labor Sociology.” Work and Occupations 50(3):316–34. doi:10.1177/07308884231168042

- Cromwell, J.B., M.J. Hannan, W.C. Labys, and Michel Terraza. 1994. “Multivariate Tests for Time Series Models.” Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 07–100. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cunningham-Cook, Matthew. 2021. “Black Worker Centers: Bridging Workplace Power in the Communities.” The American Prospect. Retrieved May 10, 2024. (https://prospect.org/api/content/2cb36c04-a144-11eb-91b5-1244d5f7c7c6/).

- Davis-Faulkner, Sheri and Marilyn Sneiderman. 2020. “Moneybags for Billionaires, Body Bags for Workers: Organizing in the Time of Pandemics.” New Worker Forum 29(3):82–90. doi:10.1177/1095796020950632.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1935. Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880. New York: The Free Press.

- Dunivin, Z.O., H.Y. Yan, Jelani Ince, and Fabio Rojas. 2022. “Black Lives Matter Protests Shift Public Discourse.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119(10):e2117320119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2117320119

- Elephrame. 2023. “At Least 6,908 Black Lives Matter Protests and Other Demonstrations Have Been Held in the Past 3,271 Days.” Retrieved 2023 (https://elephrame.com/textbook/BLM/chart).

- Elk, Mike. 2018. “Justice in the Factory: How Black Lives Matter Breathed New Life into Unions.” The Guardian, February 10. (https://www.theguardian.com/us-news).

- Elk, Mike. 2020. “America’s Biggest Unions Are Bungling the Current Racial Justice Movement and Failing Their Workers of Color.” The Insider, November 1. (https://www.businessinsider.in/).

- Fine, Janice. 2005. “Community Unions and the Revival of the American Labor Movement.” Politics & Society 33(1):153–99. doi:10.1177/0032329204272553

- Fine, Janice. 2006. Workers Centers: Organizing Communities at the Edge of the Dream. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Frymer, Paul and J.M. Grumbach. 2021. “Labor Unions and White Racial Politics.” American Journal of Political Science 65(1):225–40. doi:10.1111/ajps.12537

- Furman, Jonah and Gabriel Winant. October 18, 2021. “The Strike Wave Shows the Tight Labor Market Is Ready to Pop.” Labor Notes. (https://labornotes.org).

- Givan, R.K., K.M. Roberts, and Sarah A.S. ed. 2010. The Diffusion of Social Movements. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Green, Ken. 2020. “How Unions Have Supported Black Lives Matter.” Union Track, October 13. (https://uniontrack.com).

- Hammonds, Clare and Jasmine Kerrissey. 2022. “At Work in a Pandemic: Black Workers’ Experiences of Safety on the Job.” Labor Studies Journal 47(4):383–407. doi:10.1177/0160449X221121632

- Heany, M.T. 2022. “Who are Black Lives Matter Activists? Niche Realization in a Multimovement Environment.” Perspectives on Politics 20(4):1362–85. doi:10.1017/S1537592722001281

- Isaac, Larry W. 2008. “Movement of Movements: Culture Moves in the Long Civil Rights Struggle.” Social Forces 87(1):33–63. doi:10.1353/sof.0.0086

- Isaac, Larry W. 2023. “Turning Points in U.S. Labor History, Political Culture, and the Current Upsurge in Labor Militancy.” Work and Occupations 50(3):359–67. doi:10.1177/07308884231162944

- Isaac, Larry W. and Lars Christiansen. 2002. “How the Civil Rights Movement Revitalized Labor Militancy.” American Sociological Review 67(5):722–46. doi:10.1177/000312240206700506

- Isaac, Larry W. and Larry J. Griffin. 1989. “Ahistoricism in Time-Series Analyses of Historical Process: Critique, Redirection, and Illustrations from U.S. Labor History.” American Sociological Review 54(6):873–90. doi:10.2307/2095713

- Isaac, Larry W., Steve McDonald, and Greg Lukasik. 2006. “Takin’ it from the Streets: How the Sixties Mass Movement Revitalized Unionization.” American Journal of Sociology 112(1):46–96. doi:10.1086/502692

- Johnston, Hannah. 2018. “Workplace Gains Beyond the Wagner Act: The New York Taxi Workers Alliance and Participation in Administrative Rulemaking.” Labor Studies Journal 43(2):141–65. doi:10.1177/0160449X17747397

- Joseph, P.E. 2022. The Third Reconstruction: America’s Struggle for Racial Justice in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Basic Books.

- Juravich, Tom. 2018. “Constituting Challenges in Differing Arenas of Power: Worker Centers, the Fight for $15, and Union Organizing.” Labor Studies Journal 43(2):104–17. doi:10.1177/0160449X18763441

- Kallas, Johnnie, Kathryn Ritchie, and Eli Friedman. 2023. Labor Action Tracker: 2022 Annual Report. Cornell University, ILR School. https://www.ilr.cornell.edu/faculty-and-research/labor-action-tracker/annual-report-2022.

- Kochan, T.A., Fine, J R., Bronfenbrenner, K., Naidu, S., Barnes, J., Diaz-Linhart, Y., Kallas, J., Kim, J., Minster, A., Tong, Di and Townsend, P. 2023. “An Overview of US Workers’ Current Organizing Efforts and Collective Actions.” Work and Occupations 50(3):335–50. doi:10.1177/07308884231168793

- Koopmans, Ruud. 2007. “Protest in Time and Space: The Evolution of Waves of Contention.” in pp. 19–46, The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by David Snow, Sarah Soule, and Hanspeter Kriesi. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Larson, E.D. 2016. “Black Lives Matter and Bridge Building: Labor Education for a ‘New Jim Crow’ Era.” Labor Studies Journal 41(1):36–66. doi:10.1177/0160449X16638800

- Lee, Tamara and Maite Tapia. 2023. “Intersectional Organizing: Building Solidarity Through Radical Confrontation.” Industrial Relations 62(1):78–111. doi:10.1111/irel.12322

- Long, J.S. 1997. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Maffea, Carmin. 2022. “From BLM to Generation U: How the Spirit of the Uprising Persists in Today’s Labor Movement.” Left Voice, October 22. (https://www.leftvoice.org/).

- McAdam, Doug. 1995. “‘Initiator’ and ‘Spin-Off’ Movements: Diffusion Processes in Protest Cycles.” Pp. 217–39 in Repertoires & Cycles of Collective Action, edited by Mark Traugott. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- McCarthy, Justin. 2022. “U.S. Approval of Labor Unions at Highest Point Since 1965.” Gallup Poll. (https://news.gallup.com/poll/12751/labor-unions.aspx).

- Meyer, David and Nancy Whittier. 1994. “Social Movement Spillover.” Social Problems 41(2):277–98. doi:10.2307/3096934

- Mueller, J.C. 2023. “Universality, Black Lives Matter, and the George Floyd Uprising.” Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 24(3):361–82. doi:10.1080/1600910x.2023.218717

- Murphy, Tony. 2022. “Amazon Union Victory Part of Growing Workers’ Solidarity Movement.” Workers World, April 5. (https://workers.org).

- Pierson, Paul. 2003. “Big, Slow-Moving, and … Invisible: Macrosocial Processes in the Study of Comparative Politics.” Pp. 177–207 in Comparative Historical Analysis in the Social Sciences, edited by James Mahoney and Dietrich Rueschemeyer. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ray, Rashawn. 2020. “Setting the Record Straight on the Movement for Black Lives.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 43(8):1393–401. doi:10.1080/01419870.2020.1718727

- Rolf, David. 2016. The Fight for $15: The Right Wage for a Working America. New York: The New Press.

- Rosenblum, Jonathan. 2017. Beyond $15: Immigrant Workers, Faith Activists, and the Revival of the Labor Movement. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Sallaz, J.J. and S.G. Trongone. 2023. “Toward a Field of Labor Activism.” Work and Occupations 50(3):428–35. doi:10.1177/07308884231165077

- Sewell, W.H. Jr. 1996. “Historical Events as Structural Transformations: Inventing Revolution at the Bastille.” Theory and Society 25(6):841–81. doi:10.1007/BF00159818

- Soule, S.A. and Conny Roggeband. 2019. “Diffusion Processes within and Across Movements.” Pp. 236–51 in The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by D.A. Snow, S.A. Soule, H. Kriesi, and H.J. McCammon. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Son.

- Tarrow, Sidney. 1995. “Cycles of Collective Action: Between Moments of Madness and the Repertoire of Contention.” Pp. 89–116 in Repertoires & Cycles of Collective Action, edited by Mark Traugott. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Traugott, Mark ed. 1995. Repertoires & Cycles of Collective Action. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2023. “Annual Historical Table: 1947-Present.” www.bls.gov

- Vallas, S.P. and Hannah Johnston. 2023. “Labor Unbound? Assessing the Current Surge in Labor Activism.” Work and Occupations 50(3):376–84. doi:10.1177/07308884231162929

- Voss, Kim and Rachel Sherman. 2000. “Breaking the Iron Law of Oligarchy: Union Revitalization in the American Labor Movement.” American Journal of Sociology 106(2):303–49. doi:10.1086/316963

- Wagner-Pacifici, Robin. 2010. “Theorizing the Restlessness of Events.” American Journal of Sociology 115(5):1–36. doi:10.1086/651299

- Wingfield, A.H. 2023. “Race, Repression and the Future of New Labor Activism.” Work and Occupations 50(3):351–58. doi:10.1177/07308884231162962

- Winkelman, Rainer. 2010. Econometric Analysis of Count Data. 5th ed. Berlin: Springer.

- Woodly, D.R. 2022. Reckoning: Black Lives Matter and the Democratic Necessity of Social Movements. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Young, A.A., Jr. 2023. “Resurfacing Dignity as a Tool for the Unionization of African American Lower-Tier Workers.” Work and Occupations 50(3):385–92. doi:10.1177/07308884231167082

- Zeitlin, Maurice and L.F. Weyher. 2001. “‘Black and White, Unite and Fight’: InterracialWorking-Class Solidarity and Racial Employment Equality.” American Journal of Sociology 107(2):430–67. doi:10.1086/324682

- Zhang, Letian. 2023. “Racial Inequality in Work Environments.” American Sociological Review 88(2):252–83. doi:10.1177/00031224231157303

Appendix A.

Organizations initiating strikes including racial justice demands

Unions:

Amazonians United

Communication Workers of America (CWA)

United Auto Workers (UAW)

Warehouse Workers for Justice

Brookline Educators Union (NEA)

Strippers United

Minneapolis Federation of Teachers (AFT)

National Union of Healthcare Workers

Writers Guild of America, East

Teamsters (IBT)

UNITE HERE

Alt-Labor & Other SMOs:

Fight for $15 (SEIU)

Community Change Action

Day Without Immigrants

The Atwood Center

Voces de la Frontera

Mayorales Union

Juiceland Workers Rights

Cops Off Campus

Appendix B.

Organizations initiating protests including racial justice demands

Unions:

AFL-CIO

Service Employees International Union (SEIU)

Communication Workers of America (CWA)

American Federation of Government Employees (AFGE)

Teamsters (IBT)

United Electrical (UE)

United Domestic Workers (AFSCME)

UNITE HERE

Minnesota Nurses Association (NNU)

Art Institute of Chicago Workers United (AFSCME)

City College of San Francisco (AFT)

Colorado Education Association (NEA)

Chicago Teachers Union (AFT)

Brookline Educators Union (NEA)

United Graduate Workers of UNM (UE)

UHarvard Grad Student Union (UAW)

Graduate Organized Laborers at Dartmouth

Alt-Labor & Other SMOs:

Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance

Black Lives Matter (BLM)

Coalition of Immokalee Workers

Fight for 15 (SEIU)

Fight for Our Future

Fund Excluded Workers Coalition

Immigrant Alliance for Justice and Equity

New Hampshire Alliance for Immigrants & Refugees

NOW of New Jersey

Philadelphia Labor for Black Lives Coalition

Poor Peoples Campaign

Recovery for All

Souls to the Polls

Teach the Truth – Zinn Education Project

The Food Empowerment Project

Workers Assembly Against Racism (WAAR)

Workers Defense Project