Abstract

Here, I briefly describe the history and activities of the International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS) and its predecessor the International Society of Soil Science (ISSS) in relation to some global soil science developments. The IUSS was founded in 1924 by soil scientists interested in establishing standardized methods of soil analysis and soil classification. In the past 90 years, 20 World Congresses of Soil Science were held, and thousands of smaller conferences, meetings and workshops. The IUSS has 60,000 members who are organized into Divisions, Commissions and Working Groups that deal with all aspects of soil research. The IUSS is a global soil science organization and a member of the International Council for Science (ICSU). The IUSS has initiated projects ranging from the Soil Map of the World to GlobalSoilMap that have sparked numerous global projects and activities. The soil science knowledge base has greatly expanded and research has become much more interdisciplinary and thematic. The increased specialization of soil science is a sign of vigor. The IUSS has a major task in the continued success and expansion of the soil science discipline.

1. INTRODUCTION

Soil science is a vibrant, maturing science that emerged as a discipline in the mid 1800s. The soil science discipline has been built on the fundamental sciences—chemistry, biology, physics and mathematics—and the applied sciences—earth science, hydrology, geostatistics and ecology. In essence, soil science is an applied science based on deep fundamental understandings (Hartemink Citation2015a). The application of soil science has contributed enormously to human welfare, but much of its impact remains unquantified.

Several books and papers describe developments in the various subdisciplines of soil science (e.g., Philip Citation1974; Viets Citation1977; Krupenikov Citation1992; Yaalon and Berkowicz Citation1997; Dobrovolskii Citation2001; Pachepsky and Rawls Citation2005; Brevik and Hartemink Citation2010; Churchman Citation2010). Some of the main soil science developments are: the discovery of the soil profile and the information that can be derived from it; the replacement of descriptive practices by systematic observations coupled with inductive reasoning and deductive experimentation; the massive increase in our knowledge about soil geography, properties and processes; better tools for quantifying soil at all scales; the vast increase in peer-reviewed publications; a large number of handbooks and encyclopedias; soil contributions from all over of the world; and the formation and expansion of a global scientific community. The developments have been different in different parts of the world (Hartemink Citation2002), but soil science has now reached the stage whereby data and information are increasing and widely available, knowledge and technology rapidly expand, and soil knowledge and management strategies can be transferred and applied to all parts of the world (Hartemink Citation2015a). One of the main pillars in the development of the soil science discipline has been the formation of an international learned society. The global soil science community has been formed by 90 years of efforts by the International Society of Soil Science (ISSS) and its successor the International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS). The ISSS/IUSS has played a major role in the development and promotion of soil science as a discipline. In 2000, we analyzed the progress of the past 75 years of IUSS and focused on similarities and differences between countries and continents (van Baren et al. Citation2000). This paper builds on that overview and takes stock of the past 90 years coupled to some scientific developments in the discipline. The overall objective of the paper is to highlight achievements of the IUSS in relation to the soil science discipline. Throughout this paper, the abbreviation “IUSS” is used to cover the entire period 1924–2014.

2. IUSS HISTORY

Humans have been interested in soils ever since sedentary agriculture started. Experiments with irrigation, cropping patterns, terracing and manure were conducted in several areas in the Middle east, Egypt, Greece, the Roman empire, Asia and the Americas (Brevik and Hartemink Citation2010). Although farmers continued to experiment, much of the early scientific work was forgotten by the eighteenth century when the contours of the soil science discipline emerged out of geology and chemistry.

Soil science had a regional as well as a geological or chemical focus until about the 1900s (Hartemink Citation2015a). In Western Europe, soil science largely originated in the laboratory, whereas in the USA and the Russian Empire, soil science started in the field. The amalgamation of these broad soil research groups was fundamental in the establishment of soil science as a scientific discipline (van Baren et al. Citation2000). That amalgamation largely happened because of meetings and congresses that resulted in the establishment of the ISSS in 1924. The ISSS was established at The Fourth International Conference of Pedology held in Rome from May 12 to 19, 1924. The conference was held under the patronage of the King of Italy, and under the auspices of the International Institute of Agriculture. There were 463 participants at the conference, representing 39 countries. The conference in Rome recommended more uniform methods of soil analysis, a definite nomenclature for soil classification, the preparation of agro-geological maps of Europe, the organization of soil investigations in countries where these had not yet started and an introduction to the study of soils into the curricula of intermediary and higher schools. Its primary goal was to encourage soil research worldwide (van Baren et al. Citation2000). That goal is still at the core of the IUSS.

Six commissions were established in 1924: (I) soil physics, (II) soil chemistry, (III) soil biology, (IV) nomenclature and classification of soils, (V) soil cartography and (VI) plant physiology in relation to pedology. These commissions formed the structure of the ISSS, which was founded on May 19, 1924. The draft rules were adopted unanimously. The USA was selected as the first meeting place of the ISSS, and J.G. Lipman was elected as the first president of the society. Some of the objectives, activities and administrative and scientific structure of the IUSS have more or less remained the same since 1924. In order to foster all branches of soil science and its applications, the society organizes congresses and conferences, forms commissions and working groups dealing with special issues of soil science, establishes standing committees, publishes, co-operates with organizations in similar fields of work, and is active in general public education and outreach.

The IUSS functions through its officers, and gives an overview of presidents and secretaries general of the past 90 years. The IUSS was headed by D.J. Hissink (1924–1950) and F.A. van Baren (1950–1974) for the first 50 years (). Deputy secretaries general (DSGs) have been elected since 1956, and they have been: P. Buringh (1956–1974), I. Szabolcs (1974–1990), J.H.V. van Baren (1990–2002), A.E. Hartemink (Citation2002–Citation2010) and A.B. McBratney (2010–Citation2014). Hans van Baren summarized the activities of past DSGs as follows: “Previous DSGs were famous soil scientists but had little involvement in the development of the ISSS. They were to replace the Secretary General in case he was incapacitated.” (JHV van Baren, pers. comm., 2002) The task of the officers is the daily management of the union in consultation with other IUSS officers and the council.

Table 1 International Society of Soil Science (IUSS) presidents, secretaries general and deputy secretaries general between 1924 and 2014.

3. IUSS ACTIVITIES

The IUSS provides opportunities for soil scientists to meet, establish contact and exchange ideas through the World Congresses of Soil Science, and the many meetings in between. It is hard to measure and quantify how soil science would be without all those IUSS meetings. It has created and cemented the global soil science community and fostered progress on many fronts. Since 1924, the IUSS has organized 20 World Congresses of Soil Science, each bringing together thousands of soil scientists from all over the globe. In the past 90 years, more than 20,000 papers have been presented at IUSS Congresses. Another purpose of a congress is to handle the business of the IUSS including council meetings, meetings by divisions, commissions and working groups, and various elections.

The society has conferred honorary memberships upon 94 distinguished soil scientists (). Since 2006, the prestigious Dockuchaev and von Liebig Awards have been given out ()—these are commonly seen as the Nobel prizes in soil science and are bestowed upon soil scientists who have made exceptional contributions to the discipline.

Table 2 Honorary members of the IUSS 1924–Citation2014.

Table 3 Dokuchaev and von Liebig Award receipients, 2006–2014.

The IUSS has been active in the dissemination of scientific knowledge about soils through periodicals and publications. In 1925, the periodical Proceedings of the International Society of Soil Science was published by the International Institute of Agriculture in Rome. This publication contained scientific papers and a section with abstracts of new publications. The journal Soil Research was published from 1928 onward. As a supplement to Soil Research, the periodical Official Communications of the ISSS was published from 1939 to 1943. In 1950, when contacts between ISSS members were re-established after World War II, the IUSS Bulletin was introduced and it continues to be published twice per year.

In addition to the publishing of the proceedings of the congresses, organizers of meetings from commissions and working groups are publishing proceedings of their meetings as books or as peer-reviewed journals (special issues). It is estimated that publications from over 800 such conferences have appeared since 1924.

The IUSS cooperates with a number of scientific journals that are published by commercial publishers. In 1967, a new international journal of soil science was established, Geoderma, followed some years later by Soil Biology & Biochemistry. Both have become leading journals in soil science.

The IUSS provided the international framework for the development of a soil map of the World. Soil maps covering Africa, Australia, Asia, Europe, South America and North America were presented at the 7th Congress in Madison, Wisconsin, in 1960 (Dudal and Batisse Citation1978). At the 9th World Congress of Soil Science in 1968, the first draft was presented. The complete set of the Soil Map of the World was presented at the 10th World Congress of Soil Science in 1974. The completion of the Soil Map of the World has been one of the main contributions of the IUSS (van Baren et al., Citation2000). The Soil Map of the World has found wide applications, such as: assessment of desertification, delineation of major agro-ecological zones, evaluation of global land degradation, calculation of population supporting capacity, creation of a World Reference Base for Soil Resources and creation of a global Soils and Terrain Database (Dudal and Batisse Citation1978; Oldeman and van Engelen Citation1993; Hartemink et al. Citation2013). The IUSS has endorsed two international soil classification systems: World Reference Base (IUSS Working Group WRB Citation2014) and Soil Taxonomy (Soil Survey Staff Citation2014). Both are landmarks of international cooperation.

In 1972, the IUSS became a Scientific Associate of the International Council of Scientific Unions (now International Council for Science, ICSU) which is the premier world representative body of the sciences. The IUSS became a Scientific Union Member of ICSU in 1993, representing a major scientific recognition of the soil science discipline.

Through the activities of the IUSS commissions and working groups, a large number of soil science activities have been initiated. These include the formation of a paleopedology and pedometrics commission, the revamping of soil survey programs through the activities of the Digital Soil Mapping Working Group, and the initiation of the GlobalSoilMap project that sparked a series of global soil projects and initiatives (e.g., Global Soil Partnership, Global Soil Week, Global Soil Biodiversity Initiative, Global Soil Wetness Project, etc.). There is renewed and considerable international and global cooperation that has the potential to enhance the regional impact of soil research in all parts of the world (Hartemink Citation2015a). Other initiatives of the IUSS include the World Soil Day (December 5) and contributions to the International Year of Soil 2015. The IUSS also had a formative role in the International Year of Planet Earth triennium (2007–2009) in which soils were a major theme. The international year had a large outreach program that included soil brochures and information leaflets in many languages.

4. IUSS CHANGES

The IUSS structures remained almost unchanged for 75 years, during which time the world, and science in particular, have changed considerably. In 1998, the ISSS was changed to the International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS), to stress the new status, and the recognition that there are many aspects of soil science. The IUSS statutes defined full members as the national soil science societies, their members being thereby members of IUSS also. In 2014, there were over 60,000 soil scientists in the IUSS. Until 1998, the IUSS was organized subdisciplinarily: (I) soil physics, (II) soil chemistry, (III) soil biology, (IV) soil fertility and plant nutrition, (V) soil genesis classification and cartography, (VI) soil technology, and (VII) soil mineralogy. From 1998, the IUSS has been structured with four divisions, under each of which are grouped several commissions. Divisions I and II cover the study of soils in time and space and their properties and processes, whereas Division III embraces all soil management and Division IV deals with soils and society at large. The limited number of divisions ensures that each of these is a large and active body, and makes it easier to maintain close links between the officers and the divisions. The commissions and working groups do most of the scientific work, with the support of the respective division.

A major change that has occurred in the past years is the decoupling of the position of the president from the organization of the World Congress of Soil Science. Now, the IUSS has an elected president who serves for 6 years (2 years as President Elect, 2 years as President and 2 years as Past President). The advantage is that any member can now stand for the IUSS presidency, regardless of where the congress is held.

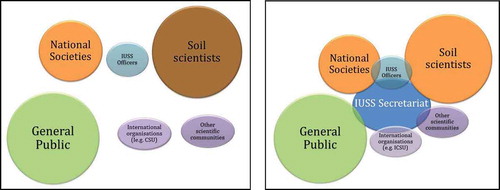

As of 2015, the IUSS has a permanent secretariat based in Vienna. After 90 years, the positions of secretary general and DSG ceased to exist, as a result of this structural reorganization. The scientific duties have been taken over by the presidential committee, whereas the administrative duties are handled by the secretariat. This is part of the increased professionalization and global service of the IUSS ().

Figure 2 Hypothetical position of IUSS and its stakeholders before the secretariat (left) and after the establishment of the secretariat (right).

In 2013, the IUSS was incorporated in the USA (IUSS Inc.) This incorporation was needed so that the IUSS could invest US $320,000 of savings into bonds and equity in the USA that provided the IUSS with a steady source of income. The IUSS doubled its net worth between 2010 and 2014.

5. SOME SOIL SCIENCE DEVELOPMENTS

Many developments have occurred in soil science in the past 90 years. At the risk of ignoring numerous aspects, I shall try to summarize some of the major developments and the way soil science is being conducted.

First, the soil science knowledge base has largely expanded. This can be measured by the vast increase in peer-reviewed publications, and the large number of new handbooks and encyclopedias summarizing and synthesizing decades of research (Hartemink Citation2012). It can be assumed that the increase reflects an increase in knowledge and scientific progress, although there is probably some repetition and recycling of ideas (more of the same, and the same but then elsewhere). A study of the impact of soil science through the analysis of peer-reviewed publications needs to be conducted. If one thing has become clear in the past decades, it is that there has been emancipation—we now have papers from all corners of the world and everyone who has a new finding or can write a paper may find a journal that will publish it.

We have better tools for quantifying soil properties and processes, although sometimes the developments in technology appear to outpace the development of sound theory. Nonetheless, the new tools and techniques provide an enormous opportunity for discoveries, breakthroughs and insights. We should encourage creativity in our teaching so that these technologies are used to the maximum. It seems that the use of soil classification is on the decline (Hartemink Citation2015b), but the development of the IUSS-led “Universal Soil Classification System” enhances efforts to the classification and understanding of soils (Hempel et al. Citation2013).

The soil science discipline has been organized by subdiscipline (e.g., soil chemistry, soil physics, pedology). These structures still exist in some soil science departments and research centers, and this is also the way the IUSS was structured until 1998. Soil science has always had strong ties to geology, earth sciences and agronomy in particular. Since the 1970s, much soil science has been conducted as part of the environmental sciences (Tinker Citation1985; Janzen et al. Citation2011; Bouma and McBratney Citation2013). Since the late 1990s, research has become much more interdisciplinary and thematic (e.g., climate, food, bioenergy), with soil security now at the center (McBratney et al. Citation2014). There is a need for more intra-disciplinary projects (e.g., soil microbiologists working with soil physicists) just as there is a need to enhance inter-disciplinary and trans-disciplinary work.

Following a decline in the 1980s, soil science departments have been merged with other departments and relabelled into, for example, the Department of Environmental Sciences or Department of Land and Water. Much of our teaching is still subdisciplinary with courses in soil physics or soil biology, whereas projects and external funding are largely thematic. There is soil science done in non-traditional soil science departments or research centers, and examples of this are the mapping work by geologists, geographers and hydrologists, and the work that is commonly labelled as biogeochemistry. This increased specialization and fragmentation of the soil science discipline is a sign of the vigor and vibrancy of the discipline. The IUSS should bring these groups into the union. It will foster the strength of the IUSS and enhance the soil science discipline.

A trend that has been discussed is the tension between applied and fundamental work (e.g., Ruellan Citation1997; Bouma Citation2010). It seems that more applied work is conducted in soil science, with many short-term funded projects (McKenzie Citation2006). Short-term projects are the result of short-term funding, and the increase in the knowledge base on soils which requires evaluation and research at different sites. Some fundamental soil research often takes place as part of applied and short-term research (Bouma Citation1998). The need for fundamental research will steadily become apparent when the increase in data and information exceeds the basic understanding of soils.

There has been a debate about declining student numbers, but it is different in different parts of the world, and overall it seems that numbers of soil science students are on the increase (Hartemink et al. Citation2008, Citation2014). Currently, very few of our soil science students have a farm background, which provided an almost natural placement to study soil science (Kemper Citation1970). The good news is that soil science is one of the most wanted professions for jobs in the UK (NERC Citation2012). But we need to provide students with sufficient field skills (Philip Citation1991), and rethinking soil science curricula is an arduous but essential task for many universities.

6. SOIL SCIENCE AND THE IUSS

The developments in soil science rapidly continue, and the IUSS as a global soil science organization has a major charge in supporting the continued success and expansion of the discipline. Soil science should develop the disciplinary base while at the same time addressing the global environmental challenges for humanities. There is a risk of becoming too applied, fragmented and harder to recognize. The IUSS should therefore embrace and invite scientists and groups that study soils (e.g., biogeochemists) but are not necessarily labelled as such. The IUSS should further increase the interaction with the general public, national soil science societies, international organizations and global projects. New alliances and structures may be needed to feed the bottom-up approach that is characteristic of the current era. The IUSS also needs to rejuvenate and have a better gender balance of its officers. Soil science expertise is now recognized to be essential at all scales and on all continents for studies on environments, agriculture, forestry, climate change and biodiversity. There are areas where information and science is needed urgently—for example, in hot spots of change and in parts of the tropics. There are also subdisciplines that need to work on scientific breakthroughs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am most thankful to my IUSS colleagues and friends for fruitful discussions and everything we do to move the soil science discipline and IUSS onward and upward.

REFERENCES

- Bouma J 1998: Realizing basic research in applied environmental research projects. Journal of Environmental Quality, 27, 742–749.

- Bouma J 2010: Implications of the knowledge paradox for soil science. Advances in Agronomy, 106, 143–171.

- Bouma J, McBratney A 2013: Framing soils as an actor when dealing with wicked environmental problems. Geoderma, 200–201, 130–139. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2013.02.011

- Brevik EC, Hartemink AE 2010: Early soil knowledge and the birth and development of soil science. Catena, 83, 23–33. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2010.06.011

- Churchman GJ 2010: The philosophical status of soil science. Geoderma, 157, 214–221. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2010.04.018

- Dobrovolskii GV 2001: Soil science at the turn of the century: Results and challenges. Eurasian Soil Science, 34, 115–119.

- Dudal R, Batisse M 1978: The soil map of the world. Nature and Resources, 14, 2–6.

- Hartemink AE 2002: Soil science in tropical and temperate regions - Some differences and similarities. Advances in Agronomy, 77, 269–292.

- Hartemink AE 2012: Soil science reference books. Catena, 95, 142–144. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2012.02.010

- Hartemink AE 2015a: On global soil science and regional solutions. Geoderma Regional, 5, 1–3. doi:10.1016/j.geodrs.2015.02.001

- Hartemink AE, 2015b. The use of soil classification in journal papers between 1975 and 2014. Geoderma Regional (in the press).

- Hartemink AE, Balks MR, Chen Z-S et al. 2014: The joy of teaching soil science. Geoderma, 217–218, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2013.10.016

- Hartemink AE, Krasilnikov P, Bockheim JG 2013: Soil maps of the world. Geoderma, 207–208, 256–267. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2013.05.003

- Hartemink AE, McBratney A, Minasny B 2008: Trends in soil science education: Looking beyond the number of students. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 63, 76a–83a. doi:10.2489/jswc.63.3.76A

- Hempel J, Micheli E, Owens P, McBratney A 2013: Universal soil classification system report from the international union of soil sciences working group. Soil Horizons, doi:10.2136/sh12-12-0035.

- IUSS Working Group WRB, 2014. World reference base for soil resources 2014. International soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps World Soil Resources Reports no. 106. FAO, Rome.

- Janzen HH, Fixen PE, Franzluebbers AJ, Hattey J, Izaurralde RC, Ketterings QM, Lobb DA, Schlesinger WH 2011: Global prospects rooted in soil science. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 75, 1–8.

- Kemper WD 1970: Environment and its role in the development of a scientist. Soil Science Society of America Proceedings, 34, 365–368.

- Krupenikov IA 1992: History of Soil Science From its Inception to the Present. Oxonian Press, New Delhi.

- McBratney AB, Field DJ, Koch A 2014: The dimensions of soil security. Geoderma, 213, 203–213. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2013.08.013

- McKenzie NJ 2006: A pedologist’s view on the future of soil science. In Ed. Hartemink, A.E., The Future of Soil Science, 89–91. IUSS, Wageningen.

- NERC 2012: Most Wanted Postgraduate and Professional Skill Needed in the Environment Sector. National Environment Research Council, Swindon, UK.

- Oldeman LR, van Engelen VWP 1993: A world soils and terrain digital database (SOTER) - an improved assessment of land resources. Geoderma, 60, 309–325. doi:10.1016/0016-7061(93)90033-H

- Pachepsky Y, Rawls WJ Eds., 2005: Developments of Pedotransfer Functions in Soil Hydrology. Developments in soil science 30Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Philip JR 1974: Fifty years progress in soil physics. Geoderma, 12, 265–280. doi:10.1016/0016-7061(74)90021-4

- Philip JR 1991: Soils, natural science, and models. Soil Science, 151, 91–98. doi:10.1097/00010694-199101000-00011

- Ruellan A 1997: Some reflections on the scientific basis of soil science. Eurasian Soil Science (Pochvovedenie), 30, 347–349.

- Soil Survey Staff, 2014. Keys to Soil Taxonomy, 12th ed. USDA National Resources Conservation Services, Washington DC.

- Tinker PB 1985: Soil science in a changing world. Journal of Soil Science, 36, 1–8. doi:10.1111/ejs.1985.36.issue-1

- van Baren H, Hartemink AE, Tinker PB 2000: 75 years the international society of soil science. Geoderma, 96, 1–18. doi:10.1016/S0016-7061(99)00097-X

- Viets FG 1977: A perspective on two centuries of progress in soil fertility and plant nutrition. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 41, 242–249.

- Yaalon DH, Berkowicz S Eds., 1997: History of Soil Science - International Perspectives. Catena Verlag, Reiskirchen.