ABSTRACT

Kinesic intelligence enables humans to understand physical movements and produce complex meanings out of them and by means of them. Grounded in embodied cognition, it elicits perceptual simulations of sensorimotor events. An attention to perceptual simulations in literature and art helps not only address readers’ and audiences’ cognitive participation in their reception of artworks, it also helps account for historical traces of cognitive acts, perceptual simulations, and kinesic intelligence in the production of artworks. This essay tests this claim in two ways. Its first part studies the text-image relationships in four medieval manuscripts containing illustrations of the psalms (the Utrecht Psalter and its English derivatives, i.e., the Harley Psalter, the Eadwine Psalter, and the Paris Psalter), while its second part focuses on a challenging line in Psalm 16: adipem suum concluserunt, comparing various translations of it over centuries and showing that its core meaning is conveyed by a sensorimotor metaphor that calls for a sustained attention to the perceptual simulations it triggers.

According to William Brown, ‘If the power of biblical poetry stems in part from the poet’s evocative use of imagery, then room needs to be made in exegesis for exploring the iconic dimensions of the psalms’ (Citation2002: 14). The medieval artists of the Utrecht Psalter and its derivatives, i.e., the Harley Psalter, the Eadwine Psalter, and the Paris Psalter (a.k.a. the Great Canterbury Psalter), responded to the iconic dimension of the psalms in remarkable ways. Whether their iconography was inspired by lost models or not, whether they were following their patrons’ instructions or not, their artistic response to the psalms is a manifestation of a remarkable level of kinesic intelligence. By referring to the teams that produced the psalters as ‘the artists’, I mean to emphasise the fact that groups of highly skilled, albeit generally anonymous, persons created the artefacts of the psalters and that the latter evince a deliberate, active, and creative form of kinesic intelligence.Footnote1

Kinesic intelligence enables humans to understand physical movements and produce complex meanings out of them and by means of them. It adapts to historical, environmental, cultural, and social contexts, which vary constantly. The presence of this competence is pervading, even though the form it takes changes (Anderson & Wheeler Citation2019).

Kinesic intelligence is grounded in embodied cognition. The theory of embodied cognition is based on recent neurophysiological and neurocognitive research, which shows that human cognition is deeply rooted in sensorimotricity (Berthoz Citation1997; Jeannerod Citation2006; Coello & Fischer Citation2016). A key aspect in this perspective is the cognitive phenomenon called perceptual simulation. Humans pre-reflectively trigger perceptual simulations when they plan physical actions (e.g., pouring water into a glass, dipping a pen into an inkwell, etc.), when they anticipate the unfolding of a gesture (e.g., moving one’s hand towards someone else’s hand to shake it), and when they process movements represented visually or described verbally (orally or in writing). Perceptual simulations elicit inferences. The sentence s/he hammered a nail into the wall tends to trigger the inference that the nail is horizontal, while the sentence s/he hammered a nail into the floor tends to trigger the inference that the nail is vertical (Stanfield & Zwaan Citation2001; Beilock & Lyons Citation2009). The cognitive acts called perceptual simulations are dynamic and pervade the ways in which we both function in everyday life and process language and pictures (Bolens Citation2012: 1–49, Citation2021: 1–18).

Differences between today’s reception of the psalms (whatever the cultural context) and that of the artists who produced the Utrecht Psalter near Rheims in the ninth century are numerous and critically significant. However, embodied cognition may provide access to a basic common ground that deserves to be explored. Regarding the dating of the psalms, Rosemary Muir Wright explains that ‘The psalms themselves may have been created over seven centuries from as early as the tenth century B.C. and some may indeed date from the time of David who was considered to be their author’ (Wright Citation2000: 1). Clearly, the risk of anachronism is high in analysing such texts and their later interpretations. Because we generally process sensorimotor information by means of perceptual simulations, my claim in this essay is that, in order to avoid anachronistic interpretations, today’s readers of the psalms and viewers of medieval psalters need to pay attention to their cognitive participation and perceptual simulations in the process of reading the psalms and looking at illuminations.

An attention to perceptual simulations in literature and art helps not only address readers’ and audiences’ cognitive participation in their reception of artworks, it also helps account for historical traces of cognitive acts, perceptual simulations, and kinesic intelligence in the production of artworks. This essay tests this claim in two ways. Its first part studies the text-image relationships in four medieval manuscripts containing illustrations of the psalms, while its second part focuses on a particularly challenging line in Psalm 16 (Ps 16:10), comparing various translations of it over centuries and showing that its core meaning is conveyed by a sensorimotor metaphor that calls for a sustained attention to the perceptual simulations it triggers. Focusing on the one hand on translations from Hebrew to Greek and Latin, and on the other hand on translations into French published during the Reformation, my aim is not to consider every existing translation, but to demonstrate the relevance of paying attention to traces of perceptual simulations in illuminated psalters and psalms translations from different historical periods.

I. Perceptual simulations in medieval illuminations of the psalms

The Utrecht Psalter (820–835; Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 32) was probably made at the Benedictine abbey of Hautvillers in the diocese of Rheims.Footnote2 Present in Canterbury by the end of the tenth century, it inspired the Harley Psalter (ca. 1010–1030; London, British Library, Harley MS 603),Footnote3 the Eadwine Psalter (1155–1160; Cambridge, Trinity College Library, MS R.17.1),Footnote4 and the Paris Psalter (ca. 1180–1200; Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS. lat. 8846).Footnote5 The three English psalters were all apparently produced in the Canterbury scriptorium of Christ Church, where the Carolingian psalter was housed for at least two centuries (Horst Citation1996: 33).

In The Utrecht Psalter in Medieval Art, Koert van der Horst writes that

decorating the psalms was not as easy as it might at first seem. Artists from late Antiquity onwards undoubtedly ran into considerable problems when it came to illustrating the psalms. How were they to depict the cries for help or deliverance from enemies, meditations on the judgment to come, prayers, eulogies and lamentations that form the greatest part of the psalms, without breaking with the centuries-old tradition and the predominant design principles of late classical text illustration? The narrative manner of giving concrete, pictorial form to the succession of often turbulent, dramatic and vivid scenes and episodes in classical texts, as well as in the historical books of the Bible and the Gospels, could not be employed for illustrating most of the psalms, for they have a totally different, non-narrative structure, and reflect the many aspects of, and feelings towards every human condition. (Horst Citation1996: 55)

To give a visual form to such feelings, the Carolingian artists of the Utrecht manuscript developed remarkable iconographic strategies.

William Noel and Lucy Freeman Sandler convincingly argue that the Utrecht Psalter as well as other psalters, such as the fourteenth-century Luttrell Psalter, contain images that look as if they were illustrations of events, while they are in fact illustrations of individual words (Noel Citation2000: 35). Sandler shows that in the Luttrell Psalter ‘the creation of images [could be] based not even on phrases, or single words, but on single syllables, which themselves are complete words – a picture-building technique familiar from rebuses and the game of charades’ (Sandler Citation1996: 92). Her conclusion is important..

I believe that the Luttrell imagines verborum represent the artist’s response to the text, not to render the psalms more readily memorable, but to provide a heightened and intensified experience of reading, through the discovery and appreciation of all the riches both apparent and concealed in the words. If the words gave rise to the images, the images disclosed the depths of meaning in the text. (Sandler Citation1996: 97)

In full agreement with Sandler’s conclusion, I wish to explore the possibility that the artists of the Utrecht Psalter made drawings not only of literal translations of phrases or words, but also of perceptual simulations, tapping into their sensorimotor understanding of scriptural similes, gestures, and kinesic interactions, thereby manifesting a heightened and intensified experience of reading the psalms.

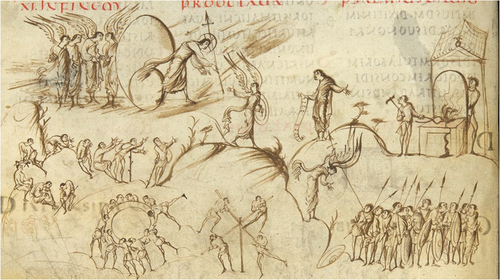

A straightforward and unproblematic trace of perceptual simulation may be found in the illustration of Psalm 11, line 7: Eloquia Domini, eloquia casta; argentum igne examinatum, probatum terræ, purgatum septuplum [The words of the Lord are pure words: (as) silver tried by the fire, purged from the earth, refined seven times].Footnote6 In the upper right section of folio 6v of the Utrecht Psalter, the idea of a purification of metal by fire is translated into the representation of a smithy where the action of melting silver could take place, a smith and his assistant exposing the metal to extreme heat (). The drawing shows the literal implication of the metaphor, meant to account for the quality of divine words as purified and precious metal. In the illustration, the smithy is a representation which provides a space for the sensorimotor association of divine words with molten metal. The representation of the smithy is the outcome of mental imagery, which in turn makes room for the related perceptual simulation of flowing silver. In the illustration of Ps 11:7, molten silver seems to be flowing down from the forge. The fact that the silver is liquid is the outcome of a perceptual simulation: the psalm is not explicit about it. The Carolingian artists turned this underspecified quality into a visible feature in their drawing. The fluidity of heated silver is the equivalent of the fact that a nail hammered into a wall is inferred to be horizontal rather than vertical.

Figure 1. The Utrecht Psalter (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 32), Psalm 11, folio 6v, https://psalter.library.uu.nl/page/20.

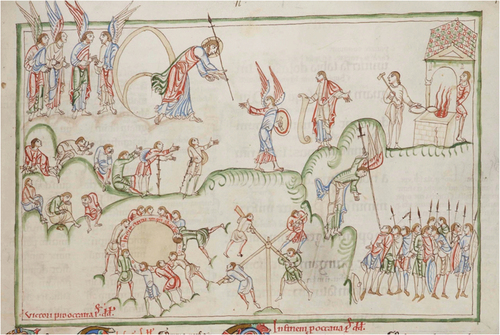

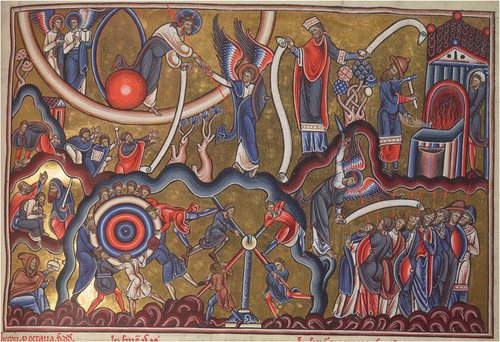

In the Harley Psalter, the flow running down from the anvil is coloured in blue, either to disambiguate the line as a flow or perhaps to specify the fact that the flow is made of water used to cool down the heated metal (). By contrast, the Eadwine Psalter reduces the flow to an almost imperceptible line (). As for the artists of the Paris Psalter, they processed the detail of flowing silver in such a way that they felt the need to add a container to collect it (). The evocation of flowing heated silver may have led to a new perceptual simulation, that of silver spilled onto the ground, which called for an iconographic supplement: a container in the form of a bucket. For, if this silver is the divine word, it must be stored and kept. The four different versions of the smithy thus contain evidence of some perceptual simulations.

Figure 2. The Harley Psalter (The British Library, Harley MS 603), Psalm 11, folio 6v, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/harley-psalter (image n° 7).

Figure 3. The Eadwine Psalter (Cambridge, Trinity College Library, MS R.17.1), Psalm 11, folio 20r, Creative Commons licence, https://mss-cat.trin.cam.ac.uk/manuscripts/uv/view.php?n=R.17.1&n=R.17.1#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=40&xywh=−986%2C-1%2C4831%2C4013).

Figure 4. The Paris Psalter (BnF MS. lat. 8846), Psalm 11, folio 20r.

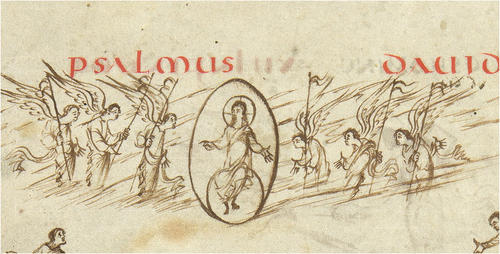

Another section of the same illustration takes such a cognitive process to a more complex level. On the upper left section of Utrecht folio 6v, line 6 of Psalm 11 is represented: Propter miseriam inopum, et gemitum pauperum, nunc exsurgam, dicit Dominus. Ponam in salutari; fiducialiter agam in eo [By reason of the misery of the needy and the groans of the poor, now will I arise, saith the Lord. I will set him in safety: I will deal confidently in his regard]. The action announced by the Lord is that he is to arise now, nunc exsurgam. The idea of surging out (ex-surgere) is visually expressed by the Lord stepping out of his mandorla. This is a notable iconographic innovation.Footnote7 Its powerful effect is based on the inferred dynamic of the Lord’s movement. The inference of intense energy in a represented body is due to a perceptual simulation involving kinaesthesia. The term kinaesthesia denotes the sensations we have when we move. When we infer specific dynamics in a perceived movement, our kinaesthetic experience of what a movement may feel like is involved. It is often the case that art historians refer to the drawings of the Utrecht Psalter as energetic or dynamic.Footnote8 By doing so, they express the outcome of their cognitive processing of movement and the nature of their kinaesthetic inferences.

The mandorla in medieval iconography constitutes a pervading symbol meant to signify holiness. It is the equivalent of the halo or nimbus but for the whole body. When represented, it visually constitutes a frame, encompassing the Lord. As frame, it affords the possibility of crossing its boundaries. What seems rather straightforward in this illumination is in fact quite extraordinary in terms of kinesic intelligence. By means of this simple iconographic solution, i.e., a frame being trespassed, the artists conveyed and visually expressed the ultimate move, that of stepping out of sacredness in order to save. The Lord surges out of his holy space to save the Psalmist or mankind (the move evoking the incarnation), handing a spear to an angel. The angel’s hurried movements are inferred from the fact that his torso is turned back to seize the spear while he keeps walking forward, which further emphasises the intensity of the scene. A decision was made that is striking in as much as it implies kinesic intelligence and an ability to signify urgency visually. The artists thought in terms of kinesis and came up with a decision: they visually translated nunc exsurgam into the Lord dynamically stepping out of his mandorla. They used sensorimotricity, spatial relationships, and the inference of dynamics and kinaesthetic sensations in their response to Psalm 11.

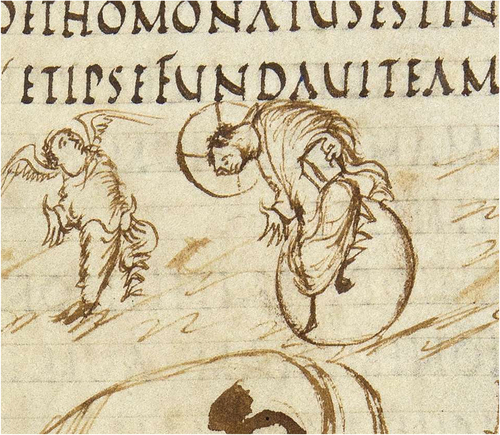

In the Utrecht Psalter, the Lord is often depicted in a mandorla, either in full, standing or sitting, or half-length. His nimbus is either marked with a cross or not. The former case possibly suggests a representation of the Son, and the latter of the Father (Noel Citation1996: 132). One drawing (folio 64v, Ps 109) represents them together sharing a round mandorla, one with a cross nimbus, the other with a plain nimbus (). They are sitting (one on a bench, the other on an orb), turned towards each other as if in conversation, one of them gesturing while presumably speaking, the other apparently listening, his right hand placed on the left knee of his interlocutor. The expressive quality of this drawing exceeds a simple representation of Ps 109:1 Dixit Dominus Domino meo: Sede a dextris meis, donec ponam inimicos tuos scabellum pedum tuorum [The Lord said to my Lord: Sit thou at my right hand: Until I make thy enemies thy footstool]. Even the enemies turned into a footstool are strikingly dynamic.

Figure 5. The Utrecht Psalter (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 32), Psalm 109, folio 64v (detail), https://psalter.library.uu.nl/page/136.

In contrast with the drawing of the Lord stepping out of his mandorla, folio 80r (illustrating Psalm 143) shows the Lord leaning forward to give a sword and shield to a warrior (). This time, his mandorla adapts to his movement and leans forward with him. Only his hands cross the boundaries of his holy space. This drawing shows an attempt at dealing with the Lord’s movements without the radical solution of having him depart from his mandorla.

Figure 6. The Utrecht Psalter (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 32), Psalm 143, folio 80r (detail), https://psalter.library.uu.nl/page/167.

When the Lord is sitting, the mandorla is habitually represented with two combined forms: the main one, almond-shaped, and a smaller one, affording sitting (e.g., ). In the Utrecht illustration of Psalm 11, the Lord’s right foot remains on the border of the mandorla, thereby increasing the impression of movement (). In the Paris Psalter, the smaller orb is fully coloured, hiding the Lord’s foot and reducing the dynamic effects found in the three other psalters, where the foot is placed in, out, or on the mandorla’s frame (). Meanwhile, the variation in the Paris Psalter emphasises the spatiality of the mandorla, suggesting that a foot can be placed behind the smaller orb and therefore be concealed by it within the mandorla.

Figure 7. The Utrecht Psalter (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 32), Psalm 13, folio 7v (detail), https://psalter.library.uu.nl/page/22.

In folio 51r (Psalm 87) of the Utrecht Psalter, spatial relationships and kinaesthetic features are combined in a representation of the Lord sitting on the smaller orb without being protected by a larger mandorla (). His precarious balance induces heightened kinaesthetic inferences, which increases the expressiveness of his solicitude for the Psalmist who is asking for help in the lower section of the illumination. The Utrecht Psalter is filled with iconographic experimentation. François Bœspflug stresses its originality and inventiveness, calling it a ‘psautier laboratoire’ [laboratory psalter] (Citation2017: 150–151). Its inventiveness often manifests itself via kinesic intelligence and an ability to think by means of sensorimotricity and spatial relationships. For William Noel, more than simply copying a model, the artists inspired by the Utrecht Psalter were knowingly transmitting instances of ‘striking, beautiful and poetic visual thinking’ (Citation1996: 132).

Figure 8. The Utrecht Psalter (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 32), Psalm 87, folio 51r (detail), https://psalter.library.uu.nl/page/109.

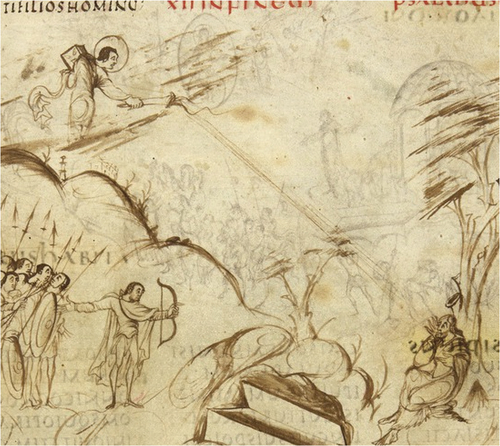

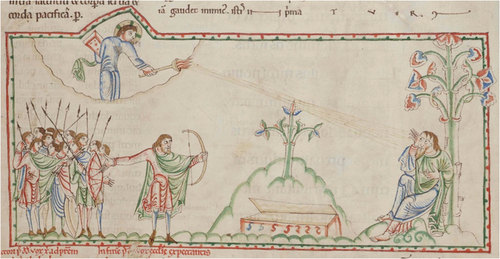

In the left lower section of the illumination of Psalm 11, line 9 is illustrated, leading to an even more remarkable iconographic solution (). Ps 11:9 reads, In circuitu impii ambulant: secundum altitudinem tuam multiplicasti filios hominum [The wicked walk round about: according to thy highness, thou hast multiplied the children of men]. In Hebrew, the first hemistich reads the wicked walk (yiṯ·hal·lā·ḵūn) around (sā·ḇîḇ), strut, or prowl on every side,Footnote9 while in the Septuagint it reads κύκλῳ οἱ ἀσεβεῖς περιπατοῦσιν.Footnote10 The original idea is that the wicked circulate around the Psalmist, maybe even circle down on him. The verb to circulate, cognate of circle, provides the general notion of a circumambient presence. The Septuagint emphasises this notion to the point of making it sound literal: the wicked are walking in circles, κύκλῳ … περιπατοῦσιν, which is echoed by the Latin translations In circuitu … ambulant in the Psalterium Romanum and Psalterium Gallicanum, and In circuitu … ambulabunt in the Psalterium Hebraicum.Footnote11

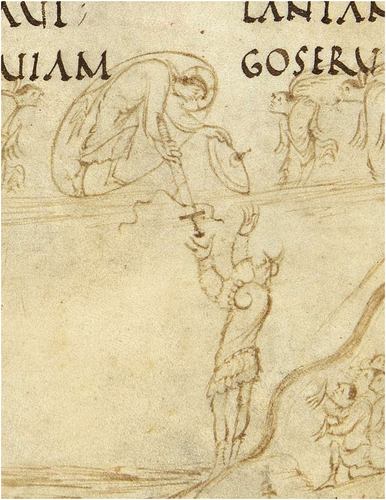

The artists of the Utrecht Psalter dealt with the Latin and the idea of ‘turning around’ by being even more literal. It is notable that they came up with two options and decided to keep them both: several men ‘walk around a circle on the ground and push a turnstile around’. This description comes from the website of the British Library and the page devoted to the Harley Psalter. Interestingly, the authors of the British Library webpage felt the need to specify the fact that the represented people are walking on the ground. This may be seen as a trace of perceptual simulation on their part, in response to a perceptual problem. This problem possibly comes from the two figures holding one leg up in the version of the same illustration in the Harley Psalter (). As viewers, we process the drawing by means of a perceptual simulation that may involve some dynamics, a dynamic strong enough to propel the upper figure in the air at the level of legs and feet. And more so in the Harley Psalter than in the Utrecht Psalter, as if the Harley artists themselves experienced such a perceptual simulation and included it when copying the Utrecht Psalter, taking it one step further, the leg being thrown higher up in the air. By contrast, the artists of the Eadwine Psalter tried to make sure viewers understood that the wicked were walking and not flying, adding a curved line representing the ground under each foot. They shared with the authors of the British Library webpage the need to disambiguate the Utrecht and Harley iconography. And they scripted Ps 11:9, for extra clarity, in the circle held by the turning men.

Medieval artists, the British Library experts, as well as any viewers today are likely to trigger perceptual simulations when responding to Psalm 11 and its illustrations. To bring the outcome of such cognitive responses to the reflective level is important to increase accuracy. A description is all the more accurate that it is transparent about the way information is processed. Verbal translations of Psalm 11 gradually mobilised the meaning of line 9 to the point of creating a newly expressive form, distinct from the original notion of a threatening group of people walking around the Psalmist. The iconographic solutions, meant to convey the idea of turning in circles in two possible ways, are eminently expressive and striking, but they depart from a representation of ill-intentioned people prowling around someone in an unwanted proximity.

Lucy Freeman Sandler notes that the translation of verbal metaphors such as the ‘wicked’ who ‘walk around’ of Psalm 11 ‘have produced direct illustrations that have attracted considerable attention – not unreasonably since they strike the post-medieval mentality as amazing perversions of the “real” meaning of words’ (Sandler Citation1996: 87). Although Sandler does not refer to specific publications, the fact that she uses the term ‘perversion’ indicates that art historians and medievalists have been primarily struck by the discrepancy between the psalm and its visual translation. For instance, Dimitri Tselos writes, ‘As a rule, the words of the Psalms provoke literal illustrations; occasionally they assume a most naïve or unwittingly amusing character’ (Citation1960: 3). And the turning men of Psalm 11 are offered as example. I wish to argue that this iconography is neither a perversion nor a sign of naiveté and witlessness. Rather, it is the trace of kinesic intelligence on the part of medieval artists, the expressive level of their illustration being that of perceptual simulations, not that of literal representations.

Before substantiating this claim further, it is worth noticing another contemporary reading of the iconography of the turning men of Psalm 11. It can be found in the remarkable website which the Utrecht University Library has created for the Utrecht Psalter. The authors of the website foreground the motif of the turning men by placing it on the home page, explaining it by the caption, ‘A drawing of the wicked and the sinners, all freaked out’.Footnote12 ‘All freaked out’ is an interesting interpretation. It is the outcome of an affective inference based on a perceptual simulation of movements, perceived as intense because of the dynamic suggested by the drawing. This is kinesic intelligence at work in response to the kinesic intelligence that presided over the Utrecht Psalter’s illumination. It involves embodied cognition and perceptual simulations in the twenty-first century as much as in the ninth. To be sure, historical, cultural, epistemological variations are paramount to the processing of such verbal and visual data. But, again, the fact that perceptual simulations are part of the processing needs to be taken into account if we are to understand fully the ways in which texts and images interrelate.

A close attention to this dimension in the illustration of Ps 11:9 may shed light on the decisions made by the medieval artists. In the present case, the iconographic solution extant in the four psalters may be meant to express the fact that the Psalmist’s enemies are not so much ‘all freaked out’ as freakish.Footnote13 Indeed, the four drawings show people making intense and pointless movements, turning around in one way or another, and each time meaninglessly, irrationally, their strenuous gestures leading nowhere (they are literally turning in circles). While it seems at first glance that the artists misunderstood the poetic idea conveyed by the psalm, it may well be that their drawings are in fact an astute way of responding to its poetry: not in the form of a representation (which would show a group of menacing people prowling around the Psalmist), but at the level of what it may feel like to see such people move in one’s space.

It is extremely difficult to describe a gait and the impact it has on others. The Psalmist refers to people walking around him. The translations emphasised the idea of circles and circuits. The medieval artists went one step further and gave a shape to the reason why it could make sense to translate the line thus. The wicked are moving in a fashion that is at once absurd and predictable for being repetitive (turning in circles as they are); their movements are strenuous, senseless, and for that very reason alarming and distressing. Subtle nuances in the copies suggest that the artists of the Christ Church scriptorium over decades grasped the point of this iconographic solution and added their own inflection to it, either in the Harley Psalter by increasing the dynamic of a leg flung high, in the Eadwine Psalter by placing a ground under every foot, or by straining the men’s efforts to the point of having their limbs intersect, as is the case in the Paris Psalter. Such aspects are so many traces of a real engagement with the psalms and of kinesic intelligence presiding over pictorial strategies.

Kinesic intelligence is even more manifest in the illustration of lines 1 and 4 of Psalm 12. Following the Psalmist’s question addressed to the Lord in line 12:1, Usquequo, Domine, oblivisceris me in finem? usquequo avertis faciem tuam a me? [How long, O Lord, wilt thou forget me unto the end? How long dost thou turn away thy face from me?], the Lord looks back in a posture that suggests a sudden turn. While doing so, he answers the Psalmist’s request in line 12:4, Respice, et exaudi me, Domine Deus meus. Illumina oculos meos, ne umquam obdormiam in morte [Consider, and hear me, O Lord my God. Enlighten my eyes that I never sleep in death]. It is astounding to see how the artists processed the two lines (). Firstly, the relationship between the Lord and the Psalmist is once again strikingly dynamic. The suddenness of the Lord's movement is conveyed by the fact that both his back and face are represented, the rotation being performed at the level of the neck. In the English psalters, the artists diversely managed the turn of the neck, but they all maintained the revolving posture.

Figure 9. The Utrecht Psalter (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, MS 32), Psalm 12, folio 7r (detail), https://psalter.library.uu.nl/page/21.

Figure 10. The Harley Psalter (The British Library, Harley MS 603), Psalm 12, folio 7r (detail), https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/harley-psalter (image n° 8).

Figure 11. The Eadwine Psalter (Cambridge, Trinity College Library, MS R.17.1), Psalm 12, folio 21r, Creative Commons licence, https://mss-cat.trin.cam.ac.uk/manuscripts/uv/view.php?n=R.17.1&n=R.17.1#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=42&xywh=27%2C862%2C2419%2C2009.

Figure 12. The Paris Psalter (BnF MS. lat. 8846), Psalm 12, folio 21r (detail).

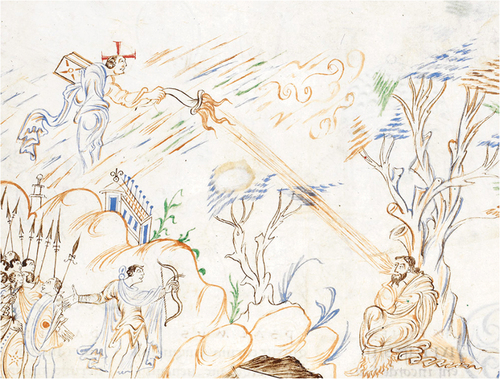

Secondly, the challenge of line 4 (Enlighten my eyes) was answered by imagining an object capable of projecting light downwards, which fire cannot be made to do (flames necessarily spring upwards). A section of folio 44v (Ps 27) of the Paris Psalter includes the two features that were merged in the illustration of Psalm 12, placing in close proximity rays projected downward by God’s hand and a torch carrying flames rising upwards (). The illustration of Ps 12:4 combines both elements into what may look today like a flashlight, that is, a pragmatically inconceivable object before the advent of electricity and batteries.Footnote14 Kinesic intelligence is manifest in the ability to use one’s sensorimotor knowledge to imagine a pragmatically impossible artefact. Rays projected by God’s hand and a torch carrying flames were merged into an object looking like a torch capable of projecting rays of light downwards, in the direction of the Psalmist’s face and eyes.

Figure 13. The Paris Psalter, Psalm 27, folio 44v (detail).

A comparison between the drawings in the four psalters shows a progression from horizontal flames projecting rays of light downward (Utrecht), to flames turned downward and extended by rays (Harley), flames slanted upward and rays running downward (Eadwine), and finally a flame-less torch with very distinct and straight rays of light streaming downward. Each version evinces an attempt at coming to terms with such an impossible device, all the more so that the Lord can send out light without any device and that such an object is never referred to in the Scriptures.

Finally, the representation of the Psalmist’s right hand is striking. His hand looks like a reaction expressive of light. This remarkably conveys the complexity of the psalm. Once again, it presupposes perceptual simulations on the part of the artists since nothing is said of the Psalmist’s hand in the text. The artists designed a gesture that looks like light, and which is expressive as gesture of the dynamic of a flash. The Psalmist asks the Lord to save him from death, which is symbolised by the sarcophagus lying open in front of him. Expressing the force of their interaction, the Psalmist’s hand gestures light as a response to the rays cast by the Lord towards his face. He reacts with this facial response, which is made manifest by a hand gesture looking like light. Such an iconographic solution is the trace of a deep understanding of the psalm, elicited by active reading. Its form evinces the activation of perceptual simulations turned into art, and it calls in turn for an active reception of the drawings by the viewers.Footnote15 This iconography is neither a narrative representation nor a charade. It is the visual trace of perceptual simulations and kinesic intelligence on the part of the medieval artists who were able to communicate about their experience of the psalm and its deepest implications. The reception of God’s light is an event which the Psalmist actively experiences and responds to in a gesture of face and hand that looks like light shining in reaction to salvific rays of light. Thus are his eyes illuminated.

The artists of the Canterbury scriptorium reproduced this iconography, increasing its readability in the Harley Psalter and the Eadwine Psalter, and replacing the hand gesture by a scroll rising in direction of God in the Paris Psalter. The blank (or un-inscribed) scroll in the latter functions like an address, the words, implied by the scroll, rising towards God while being projected from the Psalmist’s hand. This iconographic solution, which is prevalent in the Paris Psalter, interestingly corresponds to the concept of ‘visible action as utterance’ that Adam Kendon (Citation2004) applies to the concept of gesture.

In the Psalmist’s gesture of the Utrecht Psalter, reproduced in the Harley Psalter and Eadwine Psalter, the specific configuration and suggested dynamic of the hand, fingers outstretched, is the trace of a reflective perceptual simulation, similar in that respect to the horizontality of a nail in a wall or the fluidity of molten silver. It is reflective in the sense that the artists made the decision to draw it. There is strictly no reason to decide that they were not fully aware of what they were doing (whether the ideas belonged to them or had been inspired by prior sources or religious patrons). To see their illustrations as perversions of the text or signs of naiveté is to miss an important point. The illuminators were able to turn their sensorimotor perceptual simulations into artworks, and the reception of their work, manifest in later psalters, confirms the relevance of their iconographic strategies. A comparison between psalters proves instrumental to an understanding not only of the iconographic strategies that were so brilliantly developed by these medieval artists, but also of the cognitive engagement they elicited in other artists who, like their Carolingian predecessors, were clearly kinesically intelligent and trusted their readers to be so too.

II. Perceptual simulations in translations of Psalm 16:10 (Adipem suum concluserunt)

The retrieval of sensorimotor meanings in the readerly reception of a text involves perceptual simulations. When a sentence is particularly challenging, sensorimotor hypotheses are prompted, inducing a high level of cognitive effort. The various translations of the first hemistich of Ps 16:10 illustrate such a phenomenon.

The textual context of the line is the following:

8: A resistentibus dexteræ tuæ custodi me ut pupillam oculi. Sub umbra alarum tuarum protege me

9: a facie impiorum qui me afflixerunt. Inimici mei animam meam circumdederunt;

10: adipem suum concluserunt: os eorum locutum est superbiam.

11: Projicientes me nunc circumdederunt me; oculos suos statuerunt declinare in terram.

(Ps 16:8–11)

[8 From them that resist thy right hand keep me, as the apple of thy eye. Protect me under the shadow of thy wings: 9 from the face of the wicked who have afflicted me. My enemies have surrounded my soul; 10 they have shut up their fat: their mouth hath spoken proudly. 11 They have cast me forth and now they have surrounded me: they have set their eyes bowing down to the earth.]

The hemistich adipem suum concluserunt (Ps 16:10) [they have shut up their fat] is, to say the least, intriguing. To come to terms with the sensorimotor metaphor that constitutes it, a study of its translations from Hebrew to Greek and Latin is necessary, along with a comparison with other occurrences of ‘fat’ in the Scriptures. Then, a second cluster of translations, produced during the Reformation, will provide evidence of the cognitive acts performed by translators and theologians striving to make sense of the metaphor. An attention to perceptual simulations helps account for cognitive processes presiding over such translations.

The sentence adipem suum concluserunt describes a general attitude on the part of the wicked in the same way as the reference to turning men in Psalm 11 does. In Ps 16:10, the emotional and behavioural identity of the wicked is surprisingly conveyed by a metaphor involving an action related to fat. The retrieval of this metaphorical meaning involves sensorimotor perceptual simulations, which became gradually more problematic as centuries passed. Such interpretive difficulties highlight the very cognitive acts performed when metaphors are processed: sensorimotor hypotheses are tried out. The more challenging the trope, the more obvious the readers’ cognitive participation is.

Over centuries, the processing of Ps 16:10 led to various solutions, which tended to focus on what the wicked look like. Learning from the artists of the psalters studied in the first section of this essay, I propose that a more compelling option might be to focus on the feelings produced by an interaction with the wicked. Rather than what the wicked look like, the psalm may be referring to what an interaction with the wicked feels like, regardless of their looks.

In Hebrew, the term used in Ps 16:10 to refer to fat is ḥê·leḇ. It occurs repeatedly in the Old Testament in contexts manifesting its eminently positive value. It is part of Abel’s primordial offering to God in Genesis, ‘Abel also offered of the firstlings of his flock, and of their fat (ū·mê·ḥel·ḇê·hen): and the Lord had respect to Abel, and to his offerings’ (Genesis 4:4). The Septuagint translates ‘and of their fat’ by καὶ ἀπὸ τῶν στεάτων αὐτῶν, using the same term στέαρ in Ps 16:10, τὸ στέαρ αὐτῶν συνέκλεισαν [they have enclosed their fat]. Jerome’s three Latin translations systematically opt for the term adeps. In Genesis 4:4, the dative plural is used: et de adipibus eorum. In Psalm 16:10, the Psalterium Gallicanum and Psalterium Romanum read adipem suum concluserunt, while the Psalterium Hebraicum has adipe suo concluserunt. Rather than the accusative singular, the Hebraicum uses the ablative singular of adeps ‘fat’. The verb concludere means ‘to close, shut up, confine, contain, limit’. In the Gallicanum and Romanum, the wicked ‘closed their fat’; in the Hebraicum, ‘they closed (something) by means of their fat’.

The term ḥê·leḇ is used in idioms conveying a sense of abundance and density – for instance, ‘the marrow (ḥê·leḇ) of the land’ (Genesis 45:18, medullam terræ); ‘the fat (ḥê·leḇ) of corn’ (Ps 147:14, adipe frumenti); ‘the fat (mê·ḥê·leḇ) of wheat’ (Ps 80:17, adipe frumenti). A remarkable occurrence of ḥê·leḇ is extant in Psalm 62. The Psalmist addresses God, saying, ‘Let my soul be filled as with marrow (ḥê·leḇ) and fatness (wā-ḏe-šen): and my mouth shall praise thee with joyful lips’ (Ps 62:6), Sicut adipe et pinguedine repleatur anima mea, et labiis exsultationis laudabit os meum. Interestingly, the Douay-Rheims Bible here translates adipe by ‘marrow’. In the translation of this line, the Septuagint opts again for στέαρ: ὡσεὶ στέατος (fat) καὶ πιότητος (fattiness) ἐμπλησθείη ἡ ψυχή μου, καὶ χείλη ἀγαλλιάσεως αἰνέσει τὸ στόμα μου (62:6).

The notion conveyed by ḥê·leḇ seems to be that of a quintessential and nourishing substance, which may be found in plants as well as animals. Idan Dershowitz argues that the idiom regularly translated by ‘a land flowing with milk and honey’ would be more accurately translated by ‘a land flowing with fat and honey’ (Citation2010: 172–176). Indeed, ḥê·leḇ (fat) rather than ḥā·lāḇ (milk) ought to be read in the idiom, vowels being unscripted in Hebrew. The term is synonymous with abundance, a meaning that is maintained even in negative contexts. For example, in Ps 73:7 mê·ḥê·leḇ, extant in ‘the fat (mê·ḥê·leḇ) of wheat’ (Ps 80:17, adipe frumenti), is used to describe the facial expression of the wicked: ‘Their eyes bulge with abundance (mê·ḥê·leḇ); they have more than their heart could wish’.Footnote16 In Job 15:26–27, Eliphaz describes the wicked man running against God, stretching his hand in acts of defiance, his face covered with bə·ḥel·bōw (fatness, richness, abundance) and his sides made heavy (pî·māh). In the Vulgate, this passage reads, Cucurrit adversus eum erecto collo, et pingui cervice armatus est. Operuit faciem ejus crassitudo, et de lateribus ejus arvina dependet [He (the wicked) hath run against him (the Lord) with his neck raised up, and is armed with a fat neck. Fatness (crassitudo) hath covered his face, and the fat (arvina) hangeth down on his sides] (Job 15:26–27). Negative connotations attributed to ḥê·leḇ are misleading. The context in Job 15 is clearly negative but the meaning of ‘abundance’ remains positive. A face and flanks covered with ḥê·leḇ suggest a behaviour of arrogant exhibition whereby wealth is used by the wicked as a form of interpersonal and blasphemous aggression.

The same applies to oil (še·men), that is, the very substance of anointment, libation, and consecration (e.g., Genesis 28:18; Exodus 29:7; Exodus 40:9; Leviticus 8:10; Leviticus 21:12, and many more). Although the term may occur in negative contexts and metaphors, it does not turn oil into a negative substance. Rather, it suggests that its superlative and vital qualities are perverted by the behaviour of the wicked. Nevertheless, the Vulgate adapts the translation of še·men to its contexts of use. In Jeremiah 5:28, the term šā·mə·nū becomes Incrassati sunt et impinguati [They are grown gross and fat], whereas the term miš·šā·men (also from še·men) is translated as oil (oleo) in Ps 103/104:15, ‘that he may make the face cheerful with oil (miš·šā·men)’ (ut exhilaret faciem in oleo). Similarly, in Ps 108/109:24, when the Psalmist suffers from deprivation, ‘My knees are weak through fasting and my flesh is feeble from lack of fatness (miš·šā·men)’ (109:24),Footnote17 the Vulgate reads Genua mea infirmata sunt a jejunio, et caro mea immutata est propter oleum [My knees are weakened through fasting: and my flesh is changed for oil] (108:24). The original meaning of oil is maintained.

Instead of turning the concept of abundance (ḥê·leḇ) into an anachronistic sense of negative physical fatness, more attention should be paid to the type of action involving ḥê·leḇ which is being described in the Scriptures. In the idiom ‘a land flowing with milk/fat and honey’, the act of flowing (zā·ḇaṯ) is central to the simile (e.g., Exodus 3:8; Deuteronomy 26:9). To return to Ps 16:10, the verb translated by closing up (sā·ḡə·rū) may be meant to evoke the opposite of flowing, that is, the way in which a fluid thickens and solidifies. Evidence of such a meaning may be found in the Septuagint and its translation of Ps 119:70. While the Hebrew in Ps 119:70 refers to fat (ka·ḥê·leḇ), the Greek refers to curdled milk: ἐτυρώθη ὡς γάλα ἡ καρδία αὐτῶν (Ps 118:70) [Their heart is curdled like milk]. This solution led to the Latin Coagulatum est sicut lac cor eorum (Ps 118:70) [Their heart is curdled like milk]. Beside the proximity between the nouns ḥê·leḇ (fat) and ḥā·lāḇ (milk), there is an analogy between congealed fat and curdled milk: both are substances of which consistency can transform and thicken. The metaphors bear on the sensorimotor aspect of this transformation, and the way the changed substance feels to touch, sight, and perhaps taste.

A heart that becomes like congealed fat or curdled milk is a heart that loses its intersubjective fluency. Communication with it is blocked like a generous and fluid substance becoming clotted or clogged. The register of the metaphors is part of the message. In a pastoral culture such as that which created the psalms, fat and milk are wholesome and intensely beneficial substances. To think in terms of their transformation is deeply relevant, more so than an association of fat with a person’s physical weight and appearance (‘weight issues’ were probably rare in those days). The register of the metaphors is sensorimotor and kinesic: sensorimotor as it is grounded in the way a substance feels to the touch, and kinesic because the metaphors qualify the way the Psalmist experiences all interactions with the wicked as occluded, hampered, and deadening. This applies to Ps 16:10 as much as Ps 118:70. In the former, ‘They have shut up their fat’ (adipem suum concluserunt) is akin to ‘Their heart is curdled like milk’. Fluency in interactions has been closed off. The abundance of ḥê·leḇ has been blocked out, not because the wicked hide their wealth, nor because excessive food consumption made them overweight, but because their behaviour impedes the profuse, soul-sustaining and marrow-like richness of fluent intersubjectivity. Abundance is with them an external attribute, something they own and use, something they exhibit with pride to attack and harm.

In Seeing the psalms: A theology of metaphor, William Brown discusses what he calls the poetics of the psalmic imagination, referring to Ricoeur:

Cast metaphorically, an image need not deny reality. Rather, it can prompt new levels of discernment. Ricoeur refers to the power of the metaphor [to] broaden the horizons of perception as iconic augmentation. In the composing and reading of poetry, creation is also discovery. By reinscribing the world, the poetic metaphor expands it.(Brown Citation2002: 9; Ricoeur Citation1984: 80)

The poetics of the psalms is intensely sensorial, its creative force eliciting a heightened understanding and expansive discovery of perceptual and emotional experiences. The psalms brim with similes grounded in meaningful sensorimotricity, communicating with great acuity about the way complex interactions may feel, whether they are positive or negative. The metaphorical meaning of Ps 16:10 stands in stark contrast with the divine response that illuminates the Psalmist’s eyes in Ps 12:4. In the former, interactions with the wicked feel deadening like a rich substance turned stale. Interactional violence is expressed by means of such a metaphor in a context where the Psalmist finds himself – and his soul – surrounded by enemies whose bullying gaze, prowling gait, and arrogant utterances make him stumble. The difference between emotions and sensorial feelings is porous, one dimension constantly feeding on the other. To express how an interaction feels, sensorimotricity, embodied cognition, and kinesic intelligence played a significant role, as they may still do today, at the level of both poetical creation and reception.

Over the centuries, the multiple translations that were written of Ps 16:10 suggest that the metaphor became gradually opaque, as negative connotations were associated with fat. Some of the French translations produced during the Reformation constitute an interesting cluster in that respect, providing evidence of the translators’ cognitive efforts when trying to make sense of the first hemistich of Ps 16:10.Footnote18

La Bible d’Olivétan (Neuchâtel: Pierre de Vingle 1535).Footnote19 Ils sont serrés de graisse et de leur bouche parlent orgueilleusement [They (the wicked) are tight with fat and speak arrogantly with their mouth].

La Bible de Châteillon (Bale: Iehan Hervage 1555).Footnote20 … Qui ont la bouche farcie de graisse, et parlent orgueilleusement [… (The wicked) Who have their mouth stuffed with fat, and speak arrogantly].

Les Pseaumes mis en rime francoise, Par Clement Marot & Theodore de Beze (Genève: François Duron 1563).Footnote21 Ils sont si gras que plus n’en peuvent/Fiers en propos & orgueilleux [They are so fat that they cannot carry on/Proud in speech & arrogant].

Jean Calvin, La Bible des pasteurs de l’Église de Genève (Genève: Jérémie des Planches 1588).Footnote22 Last major revision of the Protestant Bible in the sixteenth century. La graisse leur cache le visage, ils parlent fièrement de leur bouche [Fat covers/conceals their face, they speak arrogantly with their mouth].

In these four translations, the reference to fat is meant to vilify the verbal and behavioural pride of the wicked. But each solution offers a different reason why the fat metaphor could be meaningful. In the first, the sensorimotor hypothesis is that of a tightness induced by excessive weight; in the second, the focus is on the mouth, stuffed with fat, out of which words are blurted; in the third, fatness is a physical impediment symptomatic of arrogant excess; finally, in the fourth, fat obstructs the access to the face. Facial communication is impeded, matching the inflated speech coming out of it. All four solutions are the result of reflective perceptual simulations on the part of the translators. They are the outcome of a cognitive attempt at making sense of a contextually awkward reference to fat. They carry the trace of sixteenth-century minds grappling with perceptual hypotheses and sensorimotor possibilities as to how fat could be a defining feature of the wicked. Rather than focusing on the transformation of the substance, they place fat somewhere in or on the body of the wicked (e.g., in the mouth or on the face), notwithstanding the figural meaning attributed to the substance thus situated.

The history of theological commentaries played a part in such interpretive orientations. Negative connotations attached to fat are already suggested in Jerome’s Psalterium Hebraicum, in which Ps 118:70 reads incrassatum est velut adeps cor eorum [Their heart is like thickened fat]. The term incrassatum, from incrasso, ‘to fatten, make thick, make stout’,Footnote23 is not a priori negative, just like the term congealed is not. Yet its connotations became gradually more debasing. In Augustine’s commentary on Ps 16:10, adeps is turned into grease and slimy feelings synonymous with sinfulness: Laetitia sua pingui cooperti sunt, postea quam cupiditas eorum de scelere satiata est (Citation1956: 93) [They are entirely covered with their greasy joy (laetitia pingui), after their greed has been satiated with wickedness].

John Calvin wrote a commentary on Ps 16:10, in which ‘greasy feelings’, instead of covering the body, hides within it. In his explanation, Calvin argues that the word graisse (fat) signifies orgueil (pride, arrogance), the wicked being ‘remplis & enflez comme de graisse’ [filled and bloated as if with fat]. Emphasising the relevance of the simile, he unwraps it thus: ‘their heart is occluded with pride (estouppé de fierté) in the same way as plump people (les gens replets) find themselves seized within by their own fat (se trouvent saisis de leur graisse au dedans)’. He concedes that David may be referring to wealth rather than weight, as the wicked are all the more arrogant that they are opulent. However, he thinks (je pense) that the use of the word ‘fat’ is meant to denote a vice hidden within (un vice caché au dedans): ‘being swollen all around with presumptuousness (étant de tous côtés rebondis d’outrecuidance), the wicked know nothing of humanity (ils ne savent aucunement que c’est d’humanité)’. Indeed, ‘they burst within with arrogance (au dedans ils crèvent d’orgueil), all the more so when, instead of keeping it hidden inside, they disgorge with full mouth words of pride (dégorgent à pleine bouche paroles de fierté)’ (Calvin Citation1558: 88).

Calvin’s stylistic choices are insistently sensorial, conveying a disgust he craves to communicate. He thinks and decides what is meant in the psalm on the basis of his association of fat with excess and vices, activating negative connotations by means of idiosyncratic perceptual simulations. Fat is an interesting concept for testing the presence of perceptual simulations because it often comes with connotations, generally positive in the Scriptures and negative in exegesis.Footnote24 In 1972, to explain Ps 16:10, A. A. Anderson still asserts, ‘In the OT [Old Testament] obesity is often linked with a rebellious spirit’ (Citation1972: 150). I hope to have shown that obesity is probably not at stake, and that any negative assessment related to this notion is likely to be an anachronism.

III. Conclusion

As must be clear by now, I fully agree with William Brown’s remark that ‘room needs to be made in exegesis for exploring the iconic dimensions of the psalms’ (Brown Citation2002: 14). In this essay, I have addressed this issue from the vantage point of kinesic intelligence and perceptual simulations, showing evidence of such cognitive processes in early medieval iconography as well as in translations of the psalms from different historical periods. The kind of intelligence at work in such instances is grounded in sensorimotricity and an ability to create and understand novel configurations and art forms (verbal and visual) which, while much else may have changed, can still be grasped by human beings living centuries later. For this to be the case, we need to be lucid about the nature of our own perceptual simulations so as to avoid projecting anachronistic assumptions and biases onto the past.

To this end, philological studies, art history, and cognitive studies can join forces, doing justice to some of the most remarkable creations of artistic minds over centuries. The importance of the Book of Psalms in western cultures cannot be overrated. Its poetical force is grounded in a form of intelligence that cannot be dissociated from human embodied cognition and artists’ ability to translate sensations and feelings into meaningful sentences and drawings. In such works, the significance of kinesis is palpable in verbal and visual metaphors that express the deadening impact that senseless behaviour may have. Rather than the way the wicked look, it is the way they make the Psalmist feel that has been the focus of attention. Sensorimotor metaphors of curdled milk, congealed fat, and people turning in circles have been crafted, requiring that we pay attention to the way we process them.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Thierry Dubois, Cédric Giraud, and Greg Walker for their precious help.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Guillemette Bolens

Guillemette Bolens is Professor of Medieval English Literature and Comparative Literature at the University of Geneva. Her research interests are in the history of the body and kinesic analysis in literature and art.

Notes

1 For an excellent discussion of originality and creativity in medieval art, see Lawrence Nees: ‘In the sphere of new expression it would be easy to cite many examples in Carolingian art alone which embody a fundamentally novel and deliberate evocation of emotional and psychological intensity. One immediately thinks of the wonderfully expressive figures of the Utrecht Psalter, or of Anglo-Saxon drawings stemming from the same tradition of rapid linear draughtsmanship. Even if certain aspects of this style owe something to an earlier model or models, as has frequently been suggested, it seems to me impossible to deny the freshness and impact of such works’ (Citation1992: 93).

2 The Utrecht Psalter contains the Psalterium Gallicanum. For more on this manuscript, see Panofsky (Citation1943), Wormald (Citation1952), Tselos (Citation1959, Citation1960), Horst, Noel and Wüstefeld (Citation1996), Chazelle (Citation1997), and the website of Utrecht University Library, Curator Dr Bart Jaski: https://www.uu.nl/en/utrecht-university-library-special-collections/the-treasury/manuscripts-from-the-treasury/the-utrecht-psalter (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

3 The Harley Psalter contains the Psalterium Romanum. For more on this manuscript, see Temple (Citation1976), Backhouse (Citation1984), Gameson (Citation1993), Noel (Citation1995), and the British Library webpage: https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/harley-psalter (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

4 The Eadwine Psalter is a psalterium triplex: the three translations of the psalter attributed to Jerome are juxtaposed (Romanum, Gallicanum, Hebraicum), along with interlinear translations in Old English and Anglo-Norman French. For more on this manuscript, see Gibson, Heslop and Pfaff (Citation1992) and Karkov (Citation2015). It is available in open access at: https://www.trin.cam.ac.uk/news/wren-display-the-eadwine-psalter/ (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

5 The Paris Psalter is also a psalterium triplex. It was begun in Canterbury with fully painted miniatures instead of drawings, and it was finished in Spain around 1340–1350. It is also known as the Great Canterbury Psalter and the Anglo-Catalan Psalter. It is available in open access at: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10551125c/f1.item (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

6 Unless specified, Latin quotations of the psalms are from the Vulgate, and the English translation of the Vulgate is from the Douay-Rheims Bible.

7 In his discussion of the Utrecht Psalter, Bœspflug provides several examples of surprising representations of the Lord, who ‘is even depicted rising from his seat and departing from his mandorla which stays behind him like the back of a seat, in order to hand a spear to an angel already equipped with a shield’ (allant jusqu’à se lever de son siège et à quitter sa mandorle, laquelle reste sur place derrière lui comme le dossier d’un siège, pour tendre une lance à un ange déjà muni d’un bouclier) (Citation2017: 151). Bœspflug does not offer further comments on this iconography, but it is clear that he considers it to be unusual.

8 Evans describes the style of the Utrecht illuminations as ‘full of nervous energy’ (Citation1969: 7). For Holcomb, ‘the pages [of the Utrecht Psalter] are endowed with a palpable dynamism created by a restless line that seems to vibrate with excitement and by sprawling compositions brimming with commotion’ (Citation2009: 7). According to the authors of the Utrecht Psalter website, the style of the Utrecht drawings ‘could be described as “nervous,” “dynamic,” “surrealistic,” and “baroque”’. (https://www.uu.nl/en/utrecht-university-library-special-collections/the-treasury/manuscripts-from-the-treasury/the-utrecht-psalter) (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

9 https://biblehub.com/interlinear/psalms/12-8.htm (last accessed on 15 February 2022). Same reference for all quotations in Hebrew.

10 https://www.academic-bible.com/en/online-bibles/septuagint-lxx/read-the-bible-text/bibel/text/lesen/stelle/19/110001/119999/ch/b7ebfa0071e86280e986b6ad6e602cb7/ (last accessed on 15 February 2022). Same reference for all quotations of the Septuagint. On the Septuagint Psalter, see Schaper (Citation2014).

11 On the three Latin translations attributed to Jerome, see Horst (Citation1996: 36–37), Goins (Citation2014) and Leneghan (Citation2017). The versions are available at http://www.liberpsalmorum.info (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

12 www.uu.nl/en/utrecht-university-library-special-collections/the-treasury/manuscripts-from-the-treasury/the-utrecht-psalter (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

13 On the Utrecht website, ‘freakish’ would not have the same appealing and humorous effect as ‘all freaked out.’ The authors of the website were of course right to opt for the latter in their caption.

14 William Noel provides the following description: ‘ … the Lord holds a book and shines a torch at the hunched psalmist, who has outspread the fingers of the hand that he has risen to his cheek’ (Citation1996: 131).

15 Referring to the Utrecht Psalter, Nees writes: ‘Whether or not its unknown patron ever accorded it such attention, the imagery seems to expect, demand, and reward intimate and prolonged consideration from its beholder’ (Citation2002: 201). On the issue of reception, see Carruthers (Citation2010).

16 This translation comes from Bible Hub: https://biblehub.com/interlinear/psalms/73-7.htm (last accessed on 15 February 2022). It differs from the Vulgate, Prodiit quasi ex adipe iniquitas eorum; transierunt in affectum cordis, and the Douay-Rheims Bible, ‘Their iniquity hath come forth, as it were from fatness: they have passed into the affection of their heart’ (Ps 72:7).

17 This translation comes from Bible Hub: https://biblehub.com/interlinear/psalms/109-24.htm (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

18 On the numerous translations of the psalms written during the sixteenth century, see Jeanneret (Citation1969); on Marot’s translation of the psalms, see Reuben (Citation2000) as well as Wursten (Citation2010), chap. 3: ‘Translating the psalms’ and chap. 13: ‘Calvin and Marot on the psalms’; on the importance of the psalms for Calvin and on his role in their translation, see Pitkin (Citation1993), Weeda (Citation2002), de Greef (Citation2004), and Beeke (Citation2004).

19 https://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/doi/10.3931/e-rara-5690, p. 329 (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

20 https://www.e-rara.ch/bau_1/doi/10.3931/e-rara-7524, p. 570 (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

21 https://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/doi/10.3931/e-rara-5807, p. 35 (last accessed on 15 February 2022). The first edition came out in 1562.

22 https://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/doi/10.3931/e-rara-5871, p. 719 (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

23 https://www.online-latin-dictionary.com/ (last accessed on 15 February 2022).

24 In vol. VII: Psalms 1–72 of Reformation Commentary on Scripture, edited by Herman J. Selderhuis in Citation2015, pages 127–143 are devoted to Psalm 16(17), but line 10 is translated by ‘They close their hearts to pity; with their mouths they speak arrogantly’. The reference to fat is avoided and the line is not discussed.

References

- Anderson, Arnold Albert. 1972. The Book of Psalms. Vol. 1: Psalms 1–72. The new century Bible commentary. Ronald E. Clements & Matthew Black ( general editors). Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans and London: Marshall, Morgan & Scott.

- Anderson, Miranda & Michael Wheeler (eds.). 2019. Distributed cognition in medieval and Renaissance culture. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Augustinus. 1956. Sancti Aurelii Augustini. Enarrationes in Psalmos, vol. 1. E. Dekkers & J. Fraipont (eds.), Corpus Christianorum Series Latina (CCSL 38), Turnholt: Typograph Brepols Editores Pontificii.

- Backhouse, Janet. 1984. The making of the Harley Psalter. The British Library Journal 10(2), 97–113.

- Beeke, Joel R. 2004. Calvin on piety. In Donald K. McKim (eds.), The Cambridge companion to John Calvin, 125–152. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Beilock, Sian L. & Ian M. Lyons. 2009. Expertise and the mental simulation of action. In Keith D. Markman, William M. P. Klein & Julie A. Suhr (eds.), Handbook of imagination and mental simulation, 21–34. New York and Hove: Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Berthoz, Alain. 1997. Le sens du mouvement. Paris: Odile Jacob.

- Bœspflug, François. 2017. Dieu et ses images: Une histoire de l’Éternel dans l’art. 3e éd. Montrouge: Bayard.

- Bolens, Guillemette. 2012. The style of gestures: Embodiment and cognition in literary narrative. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Bolens, Guillemette. 2021. Kinesic humor: Literature, embodied cognition, and the dynamics of gesture, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Brown, William P. 2002. Seeing the psalms: A theology of metaphor. Louisville and London: Westminster John Knox Press.

- Brown, William P. (ed.). 2014. The Oxford handbook of the psalms. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Calvin. Le livre des Pseaumes exposé par Jehan Calvin. Avec une table fort ample des principaux points traittez és Commentaires, Genève: Conrad Badius, 1558, https://www.e-rara.ch/gep_g/doi/10.3931/e-rara-5758

- Carruthers, Mary. 2010. The concept of ductus, or journeying through a work of art. In Mary Carruthers (ed.), Rhetoric beyond words: Delight and persuasion in the arts of the middle ages, 190–213. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chazelle, Celia. 1997. Archbishops Ebo and Hincmar of Reims and the Utrecht Psalter. Speculum 72(4), 1055–1077.

- Coello, Yann & Martin H. Fischer (eds.). 2016. Foundations of embodied cognition, vol. 1: Perceptual and emotional embodiment; vol. 2: Conceptual and interactive embodiment. London & New York: Routledge.

- De Greef, Wulfert. 2004. Calvin’s writings. In Donald K. McKim (ed.), The Cambridge companion to John Calvin, 41–57. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dershowitz, Idan. 2010. A land flowing with fat and honey. Vetus Testamentum 60, 172–176.

- Douay-Rheims Bible. 1609/1955/1963. London: Catholic Truth Society.

- Evans, Michael W. 1969. Medieval drawings. London: Paul Hamlyn.

- Gameson, Richard. 1993. The Romanesque artists of the Harley 603 Psalter. In Peter Beal & Jeremy Griffiths (eds.), English manuscript studies 1100–1700, vol. 4, 24–61. London and Toronto: The British Library and University of Toronto Press.

- Gibson, Margaret, T.A. Heslop & Richard W. Pfaff. 1992. The Eadwine Psalter: Text, image, and monastic culture in twelfth-century Canterbury. London and University Park: The Modern Humanities Research Association in conjunction with The Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Goins, Scott. 2014. Jerome’s psalters. In William P. Brown (ed.), The Oxford handbook of the psalms, 185–198. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hebrew Bible: Bible Hub: https://biblehub.com

- Holcomb, Melanie. 2009. Pen and parchment: Drawing in the Middle Ages. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

- Horst, Koert van der, William Noel & Wilhelmina C.M. Wüstefeld (eds.). 1996. The Utrecht Psalter in medieval art: Picturing the psalms of David. Utrecht: HES Publishers.

- Horst, Koert van der. 1996. The Utrecht Psalter: Picturing the psalms of David. In Koert van der Horst, William Noel, and Wüstefeld (eds.), The Utrecht Psalter in medieval art: Picturing the psalms of David, 22–84. Utrecht: HES Publishers.

- Jeanneret, Michel. 1969. Poésie et tradition biblique: Recherches stylistiques sur les paraphrases des psaumes de Marot à Malherbe. Paris: José Corti.

- Jeannerod, Marc. 2006. Motor cognition: What actions tell the self. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Karkov, C. 2015. The scribe looks back: Anglo-Saxon England and the Eadwine Psalter. In Martin Brett & David A. Woodman (eds.), The long twelfth-century view of the Anglo-Saxon past, 289–306. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate.

- Kendon, Adam. 2004. Gesture: Visible action as utterance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leneghan, Francis. 2017. Introduction: A case study of psalm 50.1–3 in Old and Middle English. In Tamara Atkin & Francis Leneghan (eds.), The psalms and medieval English literature: From the conversion to the Reformation, 1–33. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer.

- McKim, Donald K. (ed.). 2004. The Cambridge companion to John Calvin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nees, Lawrence. 1992. The originality of early medieval artists. In Celia M. Chazelle (ed.), Literacy, politics, and artistic innovation in the early medieval West, 77–109. Lanham, New York and London: University Press of America.

- Nees, Lawrence. 2002. Early medieval art. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nees, Lawrence. 2021. The European context of manuscript illumination in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, 600-900. In Claire Breay & Joanna Story (eds.) with Eleanor Jackson, Manuscripts in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms: Cultures and connections, 45–65. Chicago: Four Courts Press.

- Noel, William. 1995. The Harley Psalter ( Cambridge Studies in Paleography and Codicology). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Noel, William. 1996. The Utrecht Psalter in England: Continuity and experiment. In Koert van der Horst, William Noel, and Wüstefeld (eds.), The Utrecht Psalter in medieval art: Picturing the psalms of David, 120–165. Utrecht: HES Publishers.

- Noel, William. 2000. Medieval charades and the visual syntax of the Utrecht Psalter. In Brendan Cassidy & Rosemary Muir Wright (eds.), Studies in the illustration of the psalter, 34–41. Stamford: Shaun Tyas.

- Panofsky, Dora. 1943. The textual basis of the Utrecht Psalter illustrations. The Art Bulletin 25(1), 50–58.

- Pitkin, Barbara. 1993. Imitation of David: David as a paradigm for faith in Calvin’s exegesis of the psalms. The Sixteenth Century Journal 24(4), 843–863.

- Reuben, Catherine. 2000. La traduction des psaumes de David par Clément Marot. Paris: Honoré Champion.

- Ricoeur, Paul. 1984. Time and narrative. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sandler, Lucy Freeman. 1996. The word in the text and the image in the margin: The case of the Luttrell Psalter. The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 54, 87–99. Reprinted in Sandler 2008, 45–75.

- Sandler, Lucy Freeman. 2000. The images of words in English Gothic psalters. In Brendan Cassidy & Rosemary Muir Wright (eds.), Studies in the illustration of the psalter, 67–86. Stamford: Shaun Tyas. Reprinted in Sandler 2008, 150–194.

- Sandler, Lucy Freeman. 2008. Studies in manuscript illumination 1200-1400. London: The Pindar Press.

- Schaper, Joachim. 2014. The Septuagint Psalter. In William P. Brown (ed.), The Oxford handbook of the psalms, 173–184. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Selderhuis, Herman J. (ed.). 2015. Old Testament VII: Psalms 1–72. In Reformation commentary on Scripture. Timothy George (gen. ed.) & Scott M. Manetsch (associate gen. ed.). Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP Academic.

- Septuagint. 2006. Online edition of the Septuagint based on the Septuagint edited by Alfred Rahlfs, second revised edition by Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. https://www.academic-bible.com/en/online-bibles/septuagint-lxx/copyright/

- Stanfield, Robert A. & Zwaan, Rolf A. 2001. The effect of implied orientation derived from verbal context on picture recognition. Psychological Science 12, 153–156.

- Temple, Elzbieta. 1976. Anglo-Saxon manuscripts 900–1066. Vol. 2 of A survey of manuscripts illuminated in the British Isles, J.J.G. Alexander (gen. ed.). London: Harvey Miller.

- Tselos, Dimitri. 1959. English manuscript illustration and the Utrecht Psalter. The Art Bulletin 41(2), 137–149.

- Tselos, Dimitri. 1960. The sources of the Utrecht Psalter miniatures. Minneapolis, MN and New York: Wittenborn.

- Vulgate: Biblia Sacra juxta Vulgatam Clementinam Clementine Vulgate Project: http://vulsearch.sourceforge.net/gettext.html

- Weeda, Robert. 2002. Le psautier de Calvin. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Wormald, Francis. 1952. English drawings of the tenth and eleventh centuries. London: Faber and Faber.

- Wright, Rosemary Muir. 2000. Introduction to the psalter. In Brendan Cassidy & Rosemary Muir Wright (eds.), Studies in the illustration of the psalter, 1–11. Stamford: Shaun Tyas.

- Wursten, Dick. 2010. Clément Marot and religion: A reassessment in the light of his psalm paraphrases. Leiden & Boston: Brill.