ABSTRACT

Legal texts comprise the bulk of what has survived of the medieval written legacy in the Frisian language. Texts expounding juridical matters are not usually associated today with creative writing. It is instructive, therefore, to see how in past and present scholars have tried to come to terms with a literary appreciation for the medieval Frisian law codes. An investigation into surveys of Old Frisian literature brings to light that little has changed over the past two hundred years with respect to assessing the laws’ non-legal qualities. Hence, this paper first reviews the state-of-the-art. Next, it shows possibilities which allow an escape from what has long been a stagnant approachto the sources. Recognition of the absence of a division between law and religion opens insights into the persuasive strategies employed by the anonymous authors of laws. Furthermore, when key notions such as imagination and fictionality are brought into play, the laws can be shown to belong much more to the realm of literature than has hitherto been realized.

‘Literary history in any period is a thing made—or rather in the making—and not a thing given’ (Harris Citation2000: 223).

Legal texts comprise the bulk of what has survived of the medieval written legacy in the Frisian language.Footnote1 The production dates of manuscripts that contain these texts range from the second half of the thirteenth century to the beginning of the sixteenth century. Texts expounding juridical matters are not usually associated today with creative writing. It is instructive, therefore, to see how in past and present scholars have tried to come to terms with a literary appreciation for the medieval Frisian law codes. An investigation into surveys of Old Frisian literature brings to light that little has changed over the past two hundred years with respect to assessing the laws’ non-legal qualities.Footnote2 Hence, it is the aim of this paper to first review the state-of-the-art. Next, it shows possibilities which allow an escape from what has long been a stagnant approach to the sources. In order to offer a working perspective of the cultural context in which these laws operated in medieval Frisia, I begin with a short survey of medieval Frisian literature.

1. The nature of the texts

Vernacular pragmatic literacy arrived in the Frisian lands at more or less the same time as, or perhaps a little later than, it did in neighbouring cultural spaces, such as Holland and Lower Germany. In as far as can be assessed, this important cultural game changer made itself manifest in the first quarter of the thirteenth century, probably around 1200.Footnote3 Latinity had made its appearance in Frisia much earlier, with the introduction of Christianity, around 700. Surely, reading and writing Latin was an indispensable skill, because without it the Divine Office could not be celebrated nor could sacred texts be studied. However, no centres with a literate culture flourished within the territories of the Frisians along the North Sea littoral, due to the absence of monasteries, episcopal sees and comital courts, until well into the twelfth century when the first monasteries were founded there.Footnote4 It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the few Latin documents with a Frisian provenance from before 1200 that have escaped the vicissitudes of time clearly point in a religious direction and hence are the result of ‘Latinate’ literacy: a leaf of an eleventh-century manuscript of the Acta Apostolorum from the land of HunsingoFootnote5; a twelfth-century missal, from Hellum in Fivelgo (Gumbert Citation2011: nr. 159); and fragments of two glossed psalters, from the eleventh and late twelfth centuries, respectively, of uncertain origin. The older fragment has been tentatively assigned to Egmond Abbey, on the border between Holland and West-Friesland; the younger one to the land of Fivelgo.Footnote6

So once literacy was diversified in Frisia and applied to pragmatic purposes in the vernacular, to what ends was it used?Footnote7 Some sixteen manuscripts and one incunable, ranging from the second half of the thirteenth century to the second quarter of the sixteenth, form the vehicle for the corpus of Old Frisian, composed between c. 1200 and c. 1500.Footnote8 The majority of the corpus is legal in nature, which is perhaps to be expected for a society that was constantly harassed by violent encounters. Armed conflicts abounded against various counts and bishops from outside the Frisian territories, as they did between neighbouring Frisian lands. Above all, however, violent clashes occurred between feuding factions within the Frisian lands. Freeholding peasants, not tied to the authority of any feodal landlord, established the legal framework. Elected annually on a rotating basis, judges from their ranks also administrated the various lands, and saw to it that the rules were applied and adhered to (Vries Citation2015).

This astonishing abundance of vernacular legal prose is diverse in nature. A handful of the legal codes, notably the Seventeen Statutes and the Twenty-four Landlaws, had pan-Frisian validity, but most of them were only regionally relevant. The corpus also exhibits a proliferation of extensive registers of compensations, itemising in often minute detail how much is owed by the perpetrator for inflicting a physical or social injury on a fellow Frisian.Footnote9 Oaths of varying length and complexity are spelled out in many manuscripts,Footnote10 as are other stray specimens of performative speech acts, such as scripted accusations, curses and an occasional incantation.Footnote11

In addition to a profusion of texts concerned with customary law, legal treatises discuss procedural matters step by step, as exemplified by the popular Foerdgunghe des riuchtis, a late fourteenth-century translation of the late thirteenth-century Romano-canonical manual Summa ‘Antequam’.Footnote12 The well-tested method of question and answer is used to model the didactic Haet is riocht? [What is Law?], a text introducing beginners to the principles of law. Parts of this legal catechism are based on a Latin source, but the translator also added narrative material of which the source has yet to be identified and which for that reason might well be of his own making (Gerbenzon Citation1971a; Citation1971b). Great importance was attached to this textbook, in view of its surviving in both a longer and a shorter version in seven manuscripts.Footnote13 The longer version is the result of a concerted effort to interlace the catechism with references to Roman and Frisian history, ostensibly in an attempt to have the Frisians participate in the translatio imperii or, rather, the translatio legum, from Rome down to their own shores. Once introduced into the traditions and principles of law, a person’s insight into the intricacies of jurisdiction could then be tested by posing them legal riddles (Bremmer Citation2014: 28–30).

2. Past approaches to Old Frisian literature

For an aesthetic appreciation of Old Frisian legal discourse, the tone was set by Jacob Grimm in the early nineteenth century. It proved a tone that has remained dominant in evaluative accounts to the present day. According to Grimm (Citation1816), in his programmatic essay ‘Von der Poesie im Recht’,Footnote14 it was not difficult to believe that poetry and law ‘miteinander aus einem bette aufgestanden waren’ [had risen together from the same bed; § 2], a statement as bold as it is tickling to the imagination. But then, imagination, if anything, is what characterised the Romantic Movement, of which Grimm was an influential exponent.Footnote15 Like poetry, Grimm stated, the language of the ancient laws is ‘voll lebendiger wörter und in seinem gesammten ausdruck bilderreich’ [full of lively words and rich in imagery in its entire expression; § 8]. The poetry that Grimm saw in Germanic legal prose, especially as produced by the medieval Frisians, is manifest in the frequent application of alliteration and the use of imaginative language. Imagination is present, Grimm claimed, for example, in the way spatial distance is expressed not in abstract measures of length but with reference to everyday experience: as far as the cock crows, or as far as the cat jumps. Length of time, Grimm observed, is similarly phrased in concrete descriptions, a statement he exemplified with a passage from Old Frisian law: ‘so lange der wind aus den wolken weht und die welt steht’ [as long as the wind blows from the clouds and the world is standing; § 8].

It is indicative of the persistence of Grimm’s aesthetic opinion, for the first time expressed in 1816, that the title of the most recent textbook of the history of Frisian literature, published in 2006, is called Zo lang de wind van de wolken waait. This is the Dutch translation of the Old Frisian phrase ‘alsoe langhe soe di wynd fan dae vlkenum wayth’ as found, for example, in an eternity formula in the Frethe-eth [Peace-oath] (Buma, Ebel & Tragter-Schubert Citation1977: text XLI.1).Footnote16 The chapter in this textbook devoted to Old Frisian literature was authored by Oebele Vries (Citation2006) and exemplifies the extent to which Grimm stamped the way critics have looked at Old Frisian laws for literary appreciation. Like Grimm had done two centuries earlier, Vries singles out alliteration and the use of metaphors as ‘poetic stylistic devices’ [poëtische stijlmiddelen]. In addition, the visualisation and, simultaneously, the embellishing of abstract legal rules with lively, concrete details is branded as a poetic element by Vries. To illustrate his point, he selected the Second of the Twenty-four Landlaws as the poetic culmination of particularly imaginative and heavy alliterative use of language.Footnote17 This law treats the three dire circumstances which allowed a widow to pawn or sell her minor son’s landed property in order to keep him alive. ‘Unmistakably poetic’ [Onmiskenbaar poëtisch], according to Vries, is furthermore the description of the infinitude of time by way of listing concrete examples of everlasting phenomena, such as the blowing of the wind, just mentioned. Yet, notwithstanding these ‘poetic’ elements, Vries is cautious to add that Old Frisian legal prose obviously does not belong to the domain of ‘literature proper’ [de eigenlijke literatuur]. He would therefore prefer to characterise this legal prose as ‘proto-literature’ [protolite-ratuur] (all quotations Vries Citation2006: 25). Regrettably, Vries neither defined nor even dwelt a little on what he meant by ‘literature proper’; the term ‘proto-literature’ suggests that he assumed the germ of ‘literature’ was already present in the way the laws were textually composed, but had not yet come to fruition.

Vries’s assessment of the literary nature of Old Frisian texts is representative of the state-of-the-art, which would seem to have brought us to a dead-end street.Footnote18 It is time, therefore, to reappraise what we mean with ‘Old Frisian literature’. Were such phenomena as alliteration, metaphor and imaginative use of language, when they occur in the laws, intended by their authors to ‘embellish’ [verfraaien] their texts, as Vries and others before him would have it?

3. Alliteration

In view of its often-praised presence in Old Frisian laws, it seems appropriate to begin with the stylistic figure of alliteration. From Grimm onwards the alliterative phrase in the Frisian laws was regarded not only as an aesthetic feature, it was also taken as a sign of revered antiquity (Bremmer Citation2011). In the course of the nineteenth century, the conviction took root that the Frisian laws had initially been composed in verse (Kögel Citation1897, 2: 242–259), much like Germanic alliterative poems, such as the Old English secular epic Beowulf or the Old Saxon gospel epic Heliand. In the course of time, it was argued, legal discourse had gradually transformed from the elevated plane of verse to the homely level of prose. Nevertheless, it was believed, traces of the poetic past were still visible, here and there. Some scholars even ventured to restore parts of Frisian laws to their ‘true’ former verse form. One of these passages held to have been originally arranged in verse is precisely the restriction to the validity of the Second of the previously mentioned Twenty-four Landlaws. Having first made a verse reconstruction of the prose passage, the American philologist Francis Wood (Citation1915: 479) beheld the result of his restorative efforts and commented:

This poem could not have been written for the place in which it is found. It must have originated several centuries earlier and indicates that the Frisians, like the other Germanic tribes, had a poetic spirit and a facile use of alliterative verse. It is complete in itself, a finished product of no mean merit, worthy to live in the light of the world.

Wood was so impressed by his wonderful reconstruction that, like Pygmalion, he took his own artefact for real and fell in love with it.Footnote19

As far as alliteration in legal prose is concerned, opinions on its nature started to change in the first decades after World War II. Prominent scholars, such as Stefan Sonderegger and Klaus von See, convincingly demonstrated in the 1960s that the presence of alliteration in Old English, Old Norse, and Old Frisian laws was not a feature of their old age, nor were alliterative word-pairs intended to be aesthetically pleasing, let alone an indication of the text having formerly been cast as alliterative verse. On the contrary, as von See pointed out for the Scandinavian laws, alliteration was almost completely absent from the oldest law texts only to become more common in the later Middle Ages. In other words, the presence of alliteration in a legal text was no longer indicative of its antiquity but rather of its relative novelty (von See Citation1964: esp. 84–92). Sonderegger pointed out that alliterative phrases were not necessarily intended as embellishments; they often functioned as a means to delimit the meaning of specific legal concepts. By way of illustration, the phrase setta and sella [to pawn and to sell] served to express a sliding scale in the transfer of property, while hebba and halda [to have and to hold] put across the notion not just of ownership, but of ownership for unlimited time (Sonderegger Citation1962–63: 263).

Another feature that has been taken as a poetic element in the Frisian laws is the combination, often alliterative, of an ornamental adjective and a noun. Such pairings were seen as instances of a figure of style in which the adjective is traditionally called an epitheton ornans, familiar from Homer and Virgil’s poetry (Borchling Citation1908: 21–22; Buma Citation1949: 81*–82*). Their use, according to Wybren Jan Buma, makes the legal prose so ‘colourful, lively and concrete’ (Buma Citation1961: 72: ‘gloedvol, levendig en concreet’). The following list of combinations may serve to illustrate the phenomenon. A few of the items are alliterative, but clearly alliteration is not a required condition to bind these fixed combinations together. Moreover, not all of them are unique to Old Frisian, suggesting that such collocates date back to earlier Germanic times or were loan-translations from Latin:

salte se ‘salty sea’ (Lendinara Citation2001: 263); nare nacht ‘scary (lit. ‘narrow’) night’ (Szöke Citation2014: 71–78); use Drochten ‘our Lord’Footnote20; hete hunger ‘burning (lit. ‘hot’) hunger’Footnote21; kald irsen ‘cold iron’ (i.e., ‘weapon; chains’)Footnote22; gled is ‘slippery ice’Footnote23; skene wrald ‘beautiful world’Footnote24; rad gold ‘red gold’Footnote25; hwit selver ‘white silver’Footnote26; gren lond ‘green land’Footnote27; wallande weter ‘boiling water’Footnote28; wilde Witsing ‘wild Viking’ (Bremmer Citation2020).

Modern scholarship is reluctant to explain fixed couplings of this type as compositions intended to create an aesthetic effect; instead, it has come to recognise that such collocates are a characteristic of oral expression, called aggregation (Ong Citation2002: 38–39; Bremmer Citation2014: 9). They represent time-honoured mnemonic combinations, many of which date back to long before the time that Frisian emerged as an individual branch of West Germanic (cf. Bremmer Citation2011: 87). Hunger stereotypically burns, just as the sea is stereotypically saline and the night scary. Such fixed combinations are not therefore a feature confined to Old Frisian legal prose designed to aesthetically enhance their contents; they are part and parcel of an ancient Germanic tradition of oral discourse, indeed persisting to the present day.Footnote29 However, consciously or unconsciously, people in Frisia seem to have been aware of the potency of collocates; hence new ones sprang up that seem to be confined to Old Frisian, such as wilde Witsing ‘wild Viking’.

A closer look at the aforementioned Second of the Twenty-four Landlaws will help to gain a good impression of the way Frisian laws could be phrased. It sums up the three urgent situations which allow a widowed mother to alienate her son’s property:

Thio furme ned: sa hwersa thet kind iung is fiterat and fensen nord vr hef iefta suther vr berch, sa mot thio moder hire kindis erue setta an sella an hire kind lesa and thes liwes hilpa.

Thio other ned is: Jefter erga ier wert and thi heta hunger vr thet lond fareth and thet kind hunger stera wel, sa mot thio moder hire kindis erue setta an sella an kapia hire kind kv and corn, ther ma him thet lif mithe behelpe.

Thio thredde ned is: Sa thet kind is stocnakend jefta huslas and thenna ti thiuster niwel- and nedcalda winter and thio longe thiustre nacht on tha tunan hliet, sa faret allera monna hwelic on sin hof an on sin hus an on ine warme winclen and thet wilde diar secht thera birga hli and then hola bam, alther hit sin lif one bihalde. Sa waynat an skriet thet vnierich kind and wepet thenne sine nakene lithe and sin huslase an sinne feder, ther him reda scholde with then hunger and then niwelkalda winter, thet hi sa diape <and> alsa dimme mith fior neilum is vnder eke and vnder ther molda bisleten and bithacht. Sa mot thio moder hire kindis erue setta and sella, thervmbe thet hiu ach ple and plicht, alsa longe sa hit vngerich is, thet hit noder frost ne hunger ne in fangenschip vrfare (Buma & Ebel Citation1972: text IV.2).

[‘The first urgent situation: if the child, still young, is fettered and caught north across the sea or south across the mountain, then the mother is allowed to pawn and sell her child’s patrimony and ransom her child and help it stay alive.

The second urgent situation is: if an evil year comes about and a burning hunger fares over the land and the child is bound to starve to death, then the mother is allowed to pawn and sell her child’s patrimony and buy for the child cow and corn (i.e., meat and bread) with which it can be kept alive.

The third urgent situation is: if the child is stark naked or homeless and when the dark mist and the disastrously cold winter and the long dark night spread over the fences, then each man goes to his yard and his house and his heated room, and the wild beast seeks the lee side of the mountains and the hollow tree where it can save its life. Then the underage child cries and moans and beweeps its naked limbs and its homelessness and its father that he is so deep and so dark with four nails closed in and covered under oak and under earth. Then the mother is allowed to pawn and sell her child’s patrimony, because she has the care and the duty as long as it is a minor to see to it that it perishes neither by frost nor by hunger nor in captivity’.]

It is hard to deny a certain beauty to this narrative, depicting the mother’s predicament and the orphan’s misery in such stark, deep elegiac tones,Footnote30 almost as if the author invites us to join the fatherless boy in lamenting his intense grief.Footnote31 According to Conrad Borchling, in his charming little study Poesie und Humor im altfriesischen Recht, ‘nowhere else does such an intimacy and depth of sentiment show itself than in this most exquisite jewel of Frisian legal poetry’.Footnote32 Still, it is unlikely that the one who composed this text ever intended to evoke sentimental feelings or stir up neighbourly compassion as an artistic end in itself or thought his work poetry, if only because of the pragmatic context in which it appears. Put differently, it may strike us as poetical and literary, but that does not make the passage in itself belletristic or even proto-literature. Rather than branding it as an expression of an anonymous legislator’s creative literary talent, the vivid, graphic narrative of the pitiful orphan was much more likely composed with a functional purpose: it facilitated memorising under which circumstances a mother was allowed to take the dramatic measure of pawning or even selling her underaged fatherless son’s patrimony.Footnote33

4. Genre and ideology

Another point featuring in surveys of Old Frisian literature is a tendency to categorise the texts into certain genres. Usually the reader is told what genres are absent: the medieval Frisians gifted with the word seem to have composed neither heroic epic nor courtly romance, neither religious nor secular lyrics, neither saints’ lives nor drama, and so on. In itself, this is undeniably true. Compared to surrounding literary cultures, the Frisian lands, no matter how fertile their clay soil, strike the student by the dominance of laws to such an extent that the result has almost led to a textual monoculture. Consequently, the few items that seem to deviate from this pattern have been eagerly highlighted. One such category, which Vries finds interspersed ‘in between the legal texts’ [(t)ussen de rechtsteksten], comprises ‘Old Frisian adaptations of some religious texts current at the time’ [Oudfriese bewerkingen van enkele destijds gangbare geestelijke teksten] (Vries Citation2006: 25). As the most fascinating representative of this genre Vries chose a description of the horrors that precede the end of times, better known as the Fifteen Signs of Doomsday. Regrettably, the reader is not told by what measuring stick this text can be considered the most fascinating. One could indeed easily argue the contrary: it is a dull piece of text, for its syntax is very basic and its phrasing repetitive.Footnote34 Any contextualisation of such brief texts is absent: we do not learn from Vries to what possible end these specimens of religious discourse are found scattered through the legal codices. A similar opinion is expressed by Buma and Ebel, who state that the Fifteen Signs have nothing at all to do with the manuscript’s accompanying legal contents.Footnote35 The two editors repeat this opinion elsewhere when they state that these religious pieces benefited legal life only very indirectly.Footnote36 Such a view probably rests on their – anachronistic – assumption that at the time when the laws were composed, social life in general, and legal life in particular, can be separated from the religious domain. The two domains, however, were inseparately connected. The purpose of the Fifteen Signs must therefore have been to remind all participants in lawsuits that eventually they have to stand trial themselves before the Great Judge.

In his survey, Vries (Citation2006: 27) – like others before him – also dwells on two ‘ideological motives’: the few poems that have survived are all devoted to the glorification of the Frisian freedom and the Frisian laws. They celebrate how Charlemagne rewarded the Frisians with exemption from feodal vassalship in return for their heroic support in regaining Rome from his enemies. In parenthesis, Vries adds that this conquest is fictive, supposedly to signal that it is historically untrue, i.e., from our point of view. Indeed, we are not dealing with historicity here, but with a strategy that connects the Frisian present with a distant past. It is not history as we understand it today, but ‘a textual tradition that is concerned with textual authority’.Footnote37 Vries closes his survey with a brief mention of a prose narrative, which recounts how Charlemagne outwits Redbad, king of Denmark, in an ordeal and thereupon orders twelve asegas (i.e., legal experts) to inform him of the laws of the Frisians. When they fail to comply, the king has them placed on board a rickety ship and left at the mercy of the waves. The desperate asegas then fall to their knees and pray to God for help. Their supplications are heard and a thirteenth asega appears, none other, it turns out, than Christ himself. He safely steers them to land, teaches the twelve the essentials of law, only to disappear once he has finished his instruction. The thrust of this ‘ideological’ fictional story would apparently be that the Frisians claimed a divine origin for their laws (Vries Citation2006: 28–29). Vries’ implicit suggestion is that this claim is just as fictional as the Frisians pretending to have received their freedom from Charlemagne.

However, there are other ways of approaching such texts. What, for example, if Vries had distinguished between fiction and non-fiction, or between literary prose and utilitarian prose – Gebrauchsprosa, as the Germans call it –, terms that are indispensable when it comes to a critical textual analysis? According to Abrams (Citation1985: 64), ‘fiction is any literary narrative, whether in prose or verse, which is invented instead of being an account of events that in fact happened’. If we accept that fictionality is indeed a valid criterion to help identify literature, then, according to Robert Weisberg (Citation1988–1989: 1), a leading scholar in the law and literature movement, ‘legal texts, such as statutes, constitutions, judicial opinions, and certain classic scholarly treatises’ can be parsed ‘as if they were literary works’. Following this path, new fields of research are opened for exploring the Old Frisian laws.

5. Fictionality of laws

To begin with, much of medieval Frisian law is fictional in that it presents countless instances of imagined socially disturbed situations and cases, followed by the appropriate measures to be taken when the rule is broken. Rules of this kind proliferate to such an extent that conditional constructions have become a favourite topic in Old Frisian syntactic studies (Lühr Citation2007; Brennan Citation2019). Yet, it is not just considered from a linguistic point of view that fictionality abounds in the laws. On several occasions, a collection of regulations is preceded and concluded by shorter or longer introductions and epilogues that themselves reflect a fictional mode of thought. Thus, the pan-Frisian Seventeen Statutes and Twenty-four Landlaws are both always preceded in the surviving manuscripts by a narrative prologue. This introduction informs the reader that the two codes find their origin, via a long line of German, Frankish and Roman Emperors, and from there tracing back, through Old Testament kings and prophets, with Moses the lawgiver and, ultimately, with God (Murdoch Citation1998). The First Statute of the Seventeen Statutes itself runs as follows:

Thet iste forme kest //efter kere allera Fresana andes kenenges Kerles ieft, ther thi keneng Kerl alle Fresem forief and hia mit hira fia kapeden,// thet allera monna huuelc a sinem besitte, alsa longe sa hit vnforwrocht se (Buma & Ebel Citation1967: text III.1).

[‘This is the first statute //according to the (deliberate) choice of all Frisians and King Charles’ gift, which King Charles granted to all Frisians, and (which) they bought with their money/ that each man should remain in possession of his goods, as long as he has not forfeited them’.]

The actual rule is very short, determining that each man is entitled to manage his property in peace until he commits a crime by which he loses this entitlement. What I have placed between slashes is narrative addition. It claims that the rule was decided on by the entire Frisian people as if by plebiscite and was thereupon presented to Charlemagne. In his benevolence, Charlemagne had given his approval for the statute to the entire Frisian people, not least because they had mollified his disposition by opening up their coffers. It would be precarious to explain this transaction as a reminiscence of a distant event that happened in real time, somewhere in the early ninth century, as argued by Algra (Citation1998: 7–9). Rather, the excursus forms part of the cultic memoration of Charlemagne that prevailed throughout the Holy Roman Empire, especially since the twelfth century, with Frisia as one of the principal centres of this cult (Folz Citation1950: 170–176; Johnston Citation1998: 181–182). Consequently, the addition follows a rhetorical strategy aiming to pursuade the audience of a long-time respected tradition upon which this statute reputedly rests.

Equally imaginative as the idea that Charlemagne was the legal benefactor of the Frisians is the notion that our Lord established compensations to be paid for injuries inflicted. This belief is expressed in the introduction to a list of three exceptions to the Sixteenth Statute which stipulates that every Frisian has the right to compensate any breach of the peace with his neighbours:

Tha use Drochten enda tha warld kom, tha sette hi alle firna a fia and a festa, thet thi mon nede na sa ewele den, hi ne muge tha sende mith festa and thet ferech mith fia gefelle, behalua thrim wendum (Buma & Ebel Citation1969: text VI.1).

[‘When our Lord came into this world, then he imposed on all misdeeds (amounts of) money and (periods of) fasting, so that no matter how evil a man may have acted, he can redeem his sin with fasting and his life with money, apart from three exceptions’.]

An explicit relation is constructed here between, on the one hand, Christ’s descent from the heavenly realm to the earthly, the apex of salvation history, and, on the other hand, the Frisian legal system according to which all trespasses are redeemable with fasting and money. It is noteworthy to see how redemption by means of fasting is preferred here over the secular compensation paid to avoid violent retribution. It is an indication, most likely, of their relative priority in the eyes of the man who formulated these introductory lines.

Elsewhere, a similar legislative role is ascribed to Christ in the first of a sequence of four short paragraphs dealing with the distribution and collection of wergild – ‘man-price’, the full compensation to be paid for killing a man (Buma & Ebel Citation1969: text IX.20–23). While the first and the last paragraphs are cast as narratives, the middle two just factually expound the degrees of kinship and who should pay or receive what part of the wergild.Footnote38 The sequence has rarely been commented on, tucked away as it is among some miscellaneous accretions at the end of the Hunsingo Register of Compensations. On the rare occasions it has arisen in discussion, it has been in relation to the workings of the wergild system rather than to the form in which these four paragraphs are presented.Footnote39 The first paragraph is cast as a mini-myth that recounts how the wergild was initially established and how next, in the course of unspecified time, a matrix was designed for distributing the compensation, once it had been delivered, among the next-of-kin:

Tha use Drochten ebern warth, tha warth er alle brekanden to bote ebern. Tha sette use Drochten ene nie ewa and sett’er thet forme ield bi tuelef merkum te ieldane ieftha mith tuelef ethem te vnriuchtane. Tha krungen tha friund sex merk to tha tuelef merkum, to tha setta ielde. Tha stod thiu ewe longe. Tha onesprekaden thet tha friund. Tha stod thiu sziue, wenne mane mon mith fiwertega merkum gald. Tha sette ma sex merk to tha fiwertega merkum, tha friundem te ieuwane, fiwer merk tha federfriunden, tua tha moderfriunden. Tha sette ma tha tuintegeste merk te gergewen tha fedrien. Alsa thi em eslein is, sa clagat thi sustersune and welle sin riucht hebba. Sa scel hi hebba elefta tuede blud of tha fiwertega merkem.

[‘When our Lord was born, he was born as a bot (‘boot’, i.e., remedy, compensation) for all (law)breakers. Then our Lord imposed a new law and he fixed the first wergild to be paid at (the amount of) twelve marks or (if homicide was denied by the defendant) to be exonerated with twelve oaths. Then the next-of-kin obtained six marks of the twelve, to the fixed wergild. Then this law stood for a long time. Then it (i.e., the amount) was contested by the kinsmen. Then the contest lasted until the man (i.e., the victim) was compensated with forty marks. Then they appointed six marks of the forty to be given to the kinsmen, four to the paternal relatives, two to the maternal relatives. Then the twentieth mark (i.e., two marks) was appointed as a spear-gift to the father’s brothers. When the mother’s brother is killed, the sister’s son raises a complaint and wants to have his right. Then he must be given ten two-thirds of a buld (unit of account: 1/16 mark) of these forty marks’.]

The narrator takes his audience back to that momentous event in history, when Christ was born. This moment is here to be understood, I think, not as a point in historic time and place but as a starting point in mythical time at an undetermined place, to which the origin of the most important principle of the Frisian legal system is assigned. Different from what might have been expected, perhaps, the Lord is called here neither a Saviour nor a Redeemer, but in terms congruent with the context: a Compensation for all breakers of the law. Christ himself is the wergild – the ultimate price to be paid to regain peace between two parties in the feuding society that was Frisia (Noomen Citation1999; Vries Citation2005). Next, in a sequence of eight paratactic clauses introduced by the adverb ‘then’ – typically a sign of oral narratives (Ong Citation2002: 37–38; Bremmer Citation2014: 8) – a short history of the wergild unfolds. It begins with Christ’s issuing a new law which first established the institution of the wergild – the ultimate conceivable price in the feuding society that prevailed in Frisia at the time. It is a remarkably strategic move in this introduction and disregards the fact that the New Testament had nothing whatsoever to do with the paying of wergild and the swearing of oaths – did not Christ denounce oaths and admonish his followers to let their yea be yea and nay, nay? (Matt. 5.33–37). Christ’s new law concerned the summary of Moses’ law: ‘Thv skalt minnia God thinne skippere mith renere hirta, and thinne ivinkerstena like thi selua’ (Buma & Ebel Citation1963: text I.10) [You must love God your Creator with a pure heart and your fellow-Christian like yourself]. Instead, loving one’s neighbour in the context of the Frisian legal system entailed that one knew exactly how much wergild must be paid in order to re-establish the balance of peace and justice. Hence Christ, the narrator tells us, stipulated that the proto-wergild amounted to twelve marks unless a defendant denied the accusation, in which case he must solemnly swear an oath of exoneration, supported by eleven oath-helpers. Thereupon, the kinsmen – to be understood as relatives to the second and third degree – secured their part of the wergild, to the satisfaction of all parties, it would seem, for the law was respected for an indeterminate period of time. Eventually, however, the kinsmen of a victim became dissatisfied with the compensation and a period of uncertainty began in which the amount was disputed. In time, the disagreement was settled by increasing the wergild to the amount of forty marks, with further specifications of how the money was to be portioned among the victim’s paternal and maternal kinsmen. Remarkable is the use of gergeve ‘spear-gift’, a hapax in the Old Frisian word hoard.Footnote40 Special attention is given to the sister’s son’s part in receiving the compensation, should his maternal uncle have been killed.Footnote41 The fourth and last paragraph in the sequence of short texts runs as follows:

Tha ma’t alra erest sette thet ield, tha slochma enre frowa hire brother. Tha nelde se’m nowet. Tha setten’t tha Tuelef Apostola, thet se hire brotherdel thermithe urleren hede anti dom scolde stonda a and ti ewa. Tha se tha thene brotherdel urleren hede, tha sette ma’r thene afrethe. Thet is the afrethe, thet ma hire thrimine further beta skele ieftha biriuchta tha ene szeremonne, alsa hi’t edeth.

[‘When they had first fixed it, the (amount of) wergild, then a woman’s brother was killed. Then she did not want to have it (viz., her part of the wergild). Then the Twelve Apostles established that with it (i.e., the refusal) she had lost her brother’s part. And this decree had to last for ever and ay. When she had then lost her brother’s part, then they established for her a special peace. This is the special peace, that she must be compensated one and a half as much as a man (if her brother was killed) or he (i.e., the defendant) must swear one and a half as many oaths of innocence, according to what he (the defendant) does (i.e., chooses)’.]

A few remarks are in order here. The paragraph does not open this time with a reference to Christ, but the scene of action is vaguely situated in some distant, primaeval time, when some otherwise unidentified lawmakers initiated the wergild system. These men, presumably, are indicated with the impersonal pronoun ma. At some point in time, but not too long afterwards it would seem, ‘a woman’ – here representing all women – refused to accept her due share of wergild in compensation for her brother who was killed. We are not told the reason for her refusal, but apparently it was such an enormity for the woman to scoff at the established system that Christ’s Twelve Apostles had to intervene. Their entrance brings us to a more specific mythical past. These founders of the Church here form a kind of tribunal, a body of wise men, if ever there was one. Their elevated office invests them with the authority to deliberate on a suitable solution to the woman’s brazen disturbance of the legal conventions. The Twelve Apostles pronounce that the woman – and with her all future women – was no longer entitled from then on to receive her legal share of her brother’s wergild. Theirs was an irrevocable verdict to last for eternity, that is, time without bounds. This temporal qualification places the Apostles’ decision between the two poles of mythical time, beginning and end, thus lending it an extra dimension of importance. Somehow, however, the stern measure was felt to leave women in undesirable circumstances and therefore eventually required redress. The message underlying this turn of opinion is that progressive insights may justify questioning a verdict’s objectionable outcome and taking appropriate steps to rectify it. It was then decided by, again, unidentified lawmakers, hidden behind the impersonal pronoun ma, that another nameless ‘everywoman’ would be placed under a special protection, a ‘peace’, which entitled her – and with her all future women – to one and a half times the amount of wergild a man would receive if his brother were killed; alternatively, the defendant had to swear one and a half as many oaths to exonerate himself from the accusation than when a man’s brother was concerned.

Both imaginative narratives – Christ founding the wergild system and the Twelve Apostles establishing a woman’s rights within this system – serve a similar purpose. They both communicate in general terms the mythical origin of aspects of the wergild system, around which much of the medieval Frisian legal tradition pivoted. They sandwich two texts that plainly expound the intricacies of the compensation procedures, thus imparting an overarching coherence to their collocation in the Hunsingo Register of Compensations. When read in this light, the two narratives reach a new and important cultural level that has hitherto been overlooked. The genre of compensation registers may take its origin in a Germanic, pre-Christian culture of honour (Wormald Citation2003),Footnote42 yet in the centuries after the conversion it had wholly adapted itself to a Christian world view, perhaps as a way of legitimising and renewing its legality within its new cultural environment.Footnote43

Fictional, too, is a first-person address performed by, presumably, a skilled speaker who functions as the representative of a man who has fallen victim to burglary (Buma & Ebel Citation1969: text XV). The text lacks both a proper introduction and an epilogue, so that it cannot readily be contextualised; it has been said to serve as a form or model for phrasing an accusation in the people’s assembly (van Oosten Citation1938: 19–21). This assumption already implies that the text is an imagined construction. This is how the address begins:

Ik spreke iu to fon tha liudum end fon tha frana end fon thisse selua monne, ther J hir ursien end urhered hebbat on thisse liudwrpena warue, thet hi mi sine spreka befel and wel and min word ieth, thet J ewele deden end riuchte, thet J him toforen an thiaues lestum be slepandere thiade end be vnwissa wakandum end breken sin hus uta in end therto sin inreste helde end urstelen him sines godes alsa god sa fif end fiftech merka, thera merka ec bi achta enzum, thera enzena ec bi tuintega penningum.

[‘I accuse you on behalf of the people (i.e., the local community gathered in the assembly) and the frana (legal official) and this very man here, whom you have seen and heard here in this people’s assembly, (to inform you) that he (i.e., the plaintiff) entrusted me with his (right of) address and wholly agrees with my words, (namely) that you (the defendant) have done evil against what is right, (namely) that you went to him as a thief, when people were sleeping and when it was uncertain if anyone was keeping watch, and that you broke from outside into his house and additionally into the innermost storage room and stole from his property as much as fifty-five marks, each mark at (the value of) eight ounces, each ounce at twenty pennies’.]

The accusation is dense with rhetoric: the narrator (assuming the role of forespreka, ‘someone who speaks on behalf of another, advocate’) has carefully constructed his accusation. Moving in successive steps from a large group (assembly), to the legal official (frana) to the plaintiff, he effectively illustrates that the defendant faces a solid and important line of opponents. The defendant cannot deny knowing the plaintiff, the forespreka claims, because he has just seen and heard him in the assembly. These last two verbs denote the sensory acts that are essential for constituting a valid witness (Vries Citation2011). Next, the forespreka declares he is acting with full authority on behalf of the plaintiff, emphasising the illocutionary aspects of the session, and he points out the moral extremes – right and evil – that are at stake. Then he loathes the lowliness of the defendant’s honourless act: as befitting a despicable thief, he operated in the middle of the night, when people were sleeping and off-guard.Footnote44 Vividly, the forespreka allows us to follow the burglar penetrating the plaintiff’s house step by step from outside the house right into its securest place in order to deplete it of its valuables, the worth of which he painstakingly spells out to the last penny.

The forespreka continues his address by outlining the consequences of the malicious act:

Ther brek’i on thene leida liudfrethe, ther biracht end bigripen was mith wedde end mith worde end thes frana allerhageste bon end iuue haudlesne. End biwene mi thes thet J hiude te dei scelen tha thiwede witherweddia end there thiwede bote, alsa ik iu tosocht hebbe, pent end pennegad mith alsa dena penningum, sa ther end tha londe send ieue end genzie, ther ma ku end corn mithe ield. Tha scel’i on thera liuda wera brenzia, end on thes frana, end on thes clageres.

[‘With it (i.e., this act) you have broken the proclaimed people’s peace, which was decided on and confirmed with pledge and word and with the frana’s highest ban of all and with your head ransom. And I expect that you must pledge here today to return the stolen goods and the compensation for the stolen goods, as I have demanded from you, collected and paid with such pennies as are current and accepted in this land, with which one pays cow and corn. These you must bring into the possession of the people, and of the frana and of the plaintiff’.]

In this part of his speech, the forespreka addresses the defendant’s tearing of the social fabric, so carefully constructed with a series of solemn verbal and gestural rituals, the breach of which, he asserts, can only be redeemed by paying the full wergeld. With so much at stake for the defendant, the forespreka is sure that his claim will be paid: he demands not just the return of the stolen goods but also compensation for the furtive deed itself, the latter to be recompensed in currency that is common in social traffic. Both stolen goods and compensation are to be handed over to the three parties with whom the forespreka began his accusation. In this way, the narrator neatly wraps up this part of his address in an envelope pattern (or ring composition), a mnemonic device typical of orality.Footnote45

Despite this form of closure, the forespreka is not yet done with the defendant:

Jef J ach biseke wellat, sa skel’i hiudega te dei an stride withstonda, enne strideth swera end enne otherne hera. To tha mare stride hebbe ik ju begret end thes minnera ne bikenne ik nowet. Enes eftes onderdes bidd’ic there gretene.

[‘If, however, you want to deny this, then you must defend yourself this very day in a duel, swear a duel oath and hear one. I have challenged you to the greater duel and I do not acknowledge the lesser one. I require a legally correct response to this accusation’.]

In principle, every free Frisian has the right to defend himself against an accusation with an oath of innocence. In this case, the forespreka considers the crime to be so serious that not even a trial by hot water – the ‘kettle ordeal’ – is deemed sufficient for the defendant to exonerate himself. He must engage in a legal man-to-man duel, if he insists on his innocence. The winner of the fight will then have justice on his side. The forespreka concludes his long and impressive address by requesting a proper answer from the defendant. Regrettably, we shall never know whether the text’s composer completed his scenario by staging a defendant who employed an advocate as adroit as the one we have just heard making his assertions on the plaintiff’s behalf. One thing that is clear, though, is that here we are dealing with a fine example of legal rhetoric.

6. New openings

So what if we consider legal writing as a species of literature in its own right and develop methods with which to explore its rhetorical and narratological strategies? I therefore suggest that we approach the corpus of Old Frisian legal texts by other routes than the well-trodden paths used to isolate a few aesthetically pleasing alliterations and metaphors, or to categorise the individual textual items into narrow genres and shapes. The laws should rather be taken as an integral collection composed of elements of narrative discourse, instructional writing and speech acts, set out with the intention to persuade. We should widen our expectations of what literature can be, especially medieval Frisian literature. Since the 1970s much has been done to break down established canons of literature, not just of popular literary works, but also of what were considered to be undisputable literary forms. Moreover, critics have become increasingly aware of the alterity of medieval literature.Footnote46

‘Literature’ as a term to indicate a category of ‘written work valued for superior or lasting artistic merit’ only started to be used in the nineteenth century.Footnote47 We have long been familiar with seeing literature as a form of art through which an author expresses his or her individual viewpoints, emotions and ambiguities. If we apply this narrow sense to medieval texts, we will find that precious few works conform to it. The bulk of medieval textual production is anonymous and covers a wide palette of subjects, ranging from history to liturgy, from philosophy to theology, from medicine to alchemy, from law to didactic instruction, to mention just a few polarities. However, where we have become used to keeping such forms apart, the attraction of medieval texts lies partly in that the borderlines between genres are frequently permeable and conventions fluid. Whereas poetry today is almost wholly restricted to personal, lyrical expressions, medieval authors composed world chronicles of tens of thousands of lines in verse. We are accustomed to legal discourse as a non-fiction genre, whereas fiction abounds in medieval law. Law for modern men aims above all to regulate the actions of a given community’s members and imposes penalties if these actions deviate from what is accepted under the law. Medieval Frisian law is very much customary: it claims to pass on rules and obligatory conventions that were shaped by earlier authoritative generations, aldera ‘ancestors’.Footnote48 Law is also natural, that is, a body of principles that is innate in man and endowed by God. Law, finally, is divine, that is God is the source of justice. Medieval men, in the words of John Alford (Citation1977), cherished a ‘profound faith in law as the tie that binds all things, in heaven and in earth’. The implication of this view is that law, taken as a whole, is all encompassing and does not separate secular matters from morality and religion. What better opportunity is there to demonstrate this holistic view than with Old Frisian legal literature?

Hir is eskriuin thet wi Frisa alsek londriuht hebbe and halde, sa God selua sette ande bat, thet wi hilde alle afte thing and alle riuchte thing (Buma & Ebel Citation1963: text I.1).

[‘Here is written that we Frisians have and hold such law in our land, as God himself instituted and commanded, (namely) that we should keep all lawful things and all rightful things’.]

These are the opening lines of the Prologue to the Seventeen Statutes and Twenty-four Landlaws, the two most important and cherished Frisian legal codes. The First Rüstring Manuscript even opens with two versions of the Prologue, a longer and shorter one. The shorter Prologue begins almost the same – you may want to spot the differences:

Hir is eskriuin thet wi Frisa alsek londrivcht hebbe and halde, sa God selua sette ande bat, thet wi alle rivchta thing and alle afta thing hilde and ofnade, alsa longe sa wi lifde (Buma & Ebel Citation1963: text II.1).

[‘Here is written that we Frisians have and hold such law in our land, as God himself instituted and commanded, (namely,) that we should keep all rightful things and all lawful things, and practice them, as long as we would live’.]

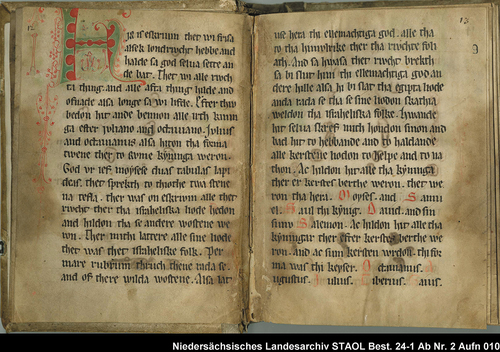

The major difference between the two is the addition in the second version that the law must not just be maintained but also implemented and practiced, emphatically, for as long as Frisians will live. The Prologue continues to relate how God wrote ‘thit riuht’ [this law] – and the only law that has been mentioned so far is the landriuht of the opening sentence – on two stone tables at the time when Moses led the Israelites through the desert. [Plate 1.] The shorter Prologue merely mentions the Ten Commandments, while the longer one spells them out, one by one, first in Latin, the lingua sacra, next in Frisian, the lingua vulgi.Footnote49 In a concluding paragraph to the Decalogue, the audience is reminded of how Moses led the Israelites through the Red Sea into the promised land, to Jerusalem, while the Egyptians were miserably locked up by the waves. Likewise, we are told in a tropological turn, those who keep these commandments will be led to the heavenly kingdom; however, those who break the law will be locked up in hell (Murdoch Citation1998: 224–225). Clearly, no distinguishing line is drawn here between divine law and secular law, an attitude that also prevailed elsewhere in Western Europe. In the words of the Miroir a Justices or Mirror of Justices, a thirteenth-century Anglo-Norman legal treatise, law is ‘nothing else but the rules laid down by our holy predecessors in Holy Writ, for the salvation of souls from eternal damnation’ (qtd. from Green Citation2002: 411). Put differently, people commonly held, whether consciously or unconsciously, that the order of law concurred with the order of salvation.

Plate 1. An ornamented initial proudly begins the prologue to the Seventeen Statutes and Twenty-four Landlaws in the First Rüstring Manuscript. The opening sentence states that ‘we Frisians have and hold such law in our land as God himself instituted and commanded’. (Oldenburg, Niedersächsiches Staatsarchiv, STAOL Best. 2, pp. 12–13; ca. 1250–75. Reproduced with permission).

The close relation between divine law as comprised by the Ten Commandments and Frisian law also surfaces in legal fiction, for example, in the so-called Legend and Statutes of Magnus. This brief narrative relates how the Frisians with their leader Magnus captured Rome for Charlemagne. It begins with a call for attention:

Wella J harkia and leta jo rathia fan tha arsta kerum ther tha Fresan kerrin tha hia an Rome thine fristol bicrongen and that strid upehewen ward tuischa thine Koning Karle and tha Romera heran umbe this Pawis agene (Bremmer Citation2009: text XV).

[‘Please listen and be instructed about the first statutes which the Frisians chose when they had won in Rome the free seat of justice and the battle was begun between King Charles and the Roman lords on account of the Pope’s (gouged-out) eyes’.]

The introductory words form an invitation to be instructed about a glorious past, phrased in direct speech by an unannounced narrator who addresses an unspecified audience. The story he goes on to tell is briefly this: in return for the Frisians’ courageously seizing Rome and defeating his enemies, Charlemagne together with Pope Leo, his brother, offer the Frisian standard bearer Magnus and his warriors all manner of material benefits, including promotion to the rank of king. Magnus, though, declines this magnanimous offer and instead prefers as a reward that all Frisians be recognised as free lords, ‘as long as the wind blows from the clouds’. Charlemagne reluctantly grants him this request. Magnus thereupon successfully asks for six more statutes with which to regulate the Frisians’ relations with the king, thus bringing the number of statutes to the solemn number of seven. When the negotiations have finally been concluded, a bishop is summoned to record the results in writing. However, before the document is handed over to Magnus, he must first ‘say it with his mouth from the table that God himself had given to the lord Moses on the mountain at Sinai’. Apparently, Magnus was required to read out the Ten Commandments. In the eyes of the narrator, the statutes that Magnus had obtained were a natural extension of God’s law. What may seem incongruous to us today was apparently self-evident to the medieval Frisians: human law and divine law are ‘merely different aspects of the same ordering principle’ (Green Citation2002: 410–411). This notion also explains why Magnus, as soon as he is handed the document, bursts out in song: ‘Crist si unse nathe, kyrioleys!’ [Christ be merciful to us, Kyrie, eleison!]. With his act of revoicing the chant ‘Christe, miserere nobis; Kyrie, eleison’, Magnus links legal transaction with liturgy, the latter being tantamount to a ritual transaction between the human and the divine. The narrator’s intentions are clear: he wants to instruct his audience and bring them all the way back to a mythical point in time when their freedom from feudal lordship began. The author’s communicating the glorious there and then into the here and now allows the audience to relive and hence to identify with this past. In effect, the purpose of The Legend and Statutes of Magnus is nothing less than to promote the building of a collective identity.

According to contemporary opinion, observing the Ten Commandments was a necessary condition for salvation. Perhaps this explains why versions of the Ten Commandments, sometimes remarkably differing in textual form, are found in no fewer than seven Frisian legal manuscripts. The readers and listeners of the Decalogue could apparently not be reminded too often that attainment of eternal bliss depended on human action – the implication of the words thet londriucht hebba and halda ‘having and (up)holding the law’. Moreover, obeying the Ten Commandments was held to result in prosperity and wealth in this sublunary life. The more people followed the Ten Commandments, the more prosperous the community would be (Buys Citation2017). So even before the man for whom the First Rüstring Manuscript was produced could begin reading the Seventeen Statutes and Twenty-four Landlaws, he had been confronted twice with a condensed version of God’s commandments.

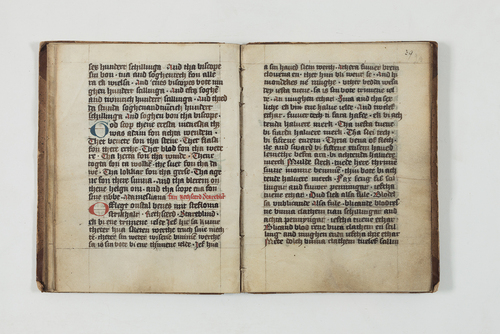

Loving God the Creator, as stipulated in the sum of the Ten Commandments, also makes a man inquisitive: sooner or later he will start to wonder how God created mankind. To satisfy this basic curiosity about where we come from, someone steeped in learning recognised the usefulness of a short Latin imaginative text, explaining how God made Adam out of eight elements and concluded his wondrous work with the creation of Eve. So this anonymous person translated Adam octopartitus, a short tract widely popular in Europe at the time, into Frisian, after which it found its way into a legal codex (Buma & Ebel Citation1967: text V.1; cf. Murdoch Citation1994). [Plate 2] On other occasions religious instruction and legal provisions are woven into one larger textual entity. This is the case with Thet Autentica Riocht (Brouwer Citation1941), a fifteenth-century treatise combining moral theology with native legal provisions, spiced with a generous dose of Roman and canon law and larded with some catechismal titbits, as discussed by Concetta Giliberto (Citation2015).Footnote50

Plate 2. Preceded by Compensations for Priests and followed by the General Register of Compensations the imaginative Adam’s Creation has been given an unobtrusive place in the First Emsingo Manuscript. A coloured Lombardic capital marks its beginning, but otherwise the scribe made no further signal to distinguish its contents from the two legal texts embracing it. (Groningen, Universiteitsbibliotheek, P.E.J.P 13, p. 38; ca. 1400. Reproduced with permission).

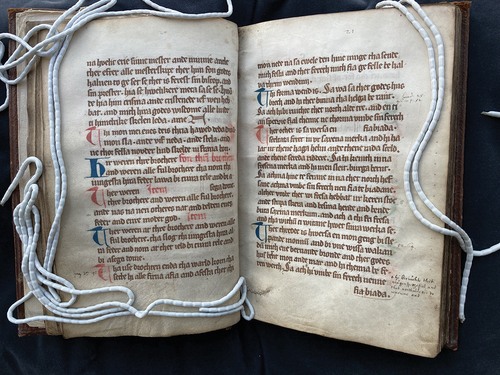

That law and literature can be considered together is also indicated by the art of riddling. [Plate 3.] A cluster of three, sometimes four, legal riddles, included in four manuscripts originating from Frisia east of the Lauwers and in two from west of that river, are another sign of the textual community that united the Frisian lands, and attest to their lasting popularity.Footnote51 Only a late manuscript, Codex Roorda, compiled around 1500, also offers the answers. Riddles have been posed all over the world and typically belong to oral cultures, right up to the present day (Ong Citation2002: 53). Through their, often ambiguous, wording they demonstrate that our reality is complex and that things are often not what they seem to be. Riddles also offer an opportunity to test and assess someone’s knowledge and ingenuity, and as such they belong to wisdom literature (Neumann Citation2003). These legal riddles have never been the subject of scholarly study; only some appreciative remarks were made by Buma and Ebel, in their edition of the Hunsingo manuscripts. They contend that these riddles can hardly be counted ‘among our sources of legal knowledge, but rather belong to folk literature’.Footnote52 Buma and Ebel do not make explicit in what respects the two genres are distinct. In any case, the scribe of the First Emsingo Manuscript clearly held a different opinion, for he begins the first riddle with the words: ‘This is landlaw that there were three brothers … ’. In doing so, he emphatically positioned the riddle within the domain of law (Bremmer Citation2014: 28–30).

Plate 3. This opening of the Second Hunsingo Manuscript shows, top left, the conclusion to Five Keys of Wisdom, followed by four riddles, each announced by a coloured Lombard. The second riddle carries the rubric ‘fon thrim brotherem’ (about three brothers), the third and the fourth have ‘Item’ as their rubric. Then follow the three exceptions, ‘wende’, to the Sixteenth Landlaw, beginning with the claim that Our Lord (‘use drochten’) established compensations and fasts for every crime. The capitals mark no hierarchic distinction for these texts. (Leeuwarden, Tresoar, R3, pp. 20–21; ca. 1325–50. Photo: Riemer Janssen. Reproduced with permission).

Another feature that stands out in the Frisian laws is the frequent occurrence of proverbs and maxims. This aspect was duly noted in the past and consequently lists with proverbs were drafted, especially as they were seen as relics of a Germanic heritage. However, scholars did little with them beyond collecting and rubricating them. It now can be demonstrated that these proverbs function as a rhetorical strategy to buttress a legal stipulation, at the same time appealing to the wisdom of both the timeless past and, often enough, to the wisdom embedded in Scripture.Footnote53

7. Conclusion

For a long time, the medieval Frisian laws have been left unexplored for their literary potential beyond such aspects as alliteration and style. However, the line between literature and law is much thinner than critics of Frisian laws have thought, especially when imagination is brought into play. Moreover, I hope to have argued against isolating from the laws the brief imaginative and instructive religious texts found scattered throughout these legal codices, because they allegedly relate only very indirectly to legal matters, if at all. Instead, I have demonstrated that law cannot be separated from religion, but that it is imperative to view the Christian worldview as a vital part of the medieval Frisian legal discourse. Such pieces show at the same time that compilers of Frisian legal manuscripts were not just focused on local or regional legal matters. Rather, they prove themselves to have been in touch with wider European traditions of wisdom and learning. The laws may have been written for the Frisians, at the same time the scribes/compilers of the legal miscellanies often showed themselves to be part of a wider, transnational literary culture, as witnessed by their inclusion of specimens of imaginative Christian literature that was circulating throughout Europe.Footnote54 Consequently, what the medieval Frisian authors and scribes a long time ago joined together should not be separated by modern critics. On the contrary, such texts should make us aware that the ambit of the law was so much wider then and hence more inclusive than it is for us today. Once this awareness is shared, the medieval Frisian legal corpus of texts offers welcome opportunities for new literary interpretations and appreciations.

Acknowledgments

Shorter versions of this paper were read at the First Conference on Frisian Hunamities, Leeuwarden, April 2018, and before an audience at the University of Zurich, October 2021. I have profitted from the feedback at these occasions and am furthermore grateful to Anne Popkema, Oebele Vries, David F. Johnson, Leonard Neidorf and Jenneka Janzen for their welcome comments on earlier drafts of this paper. My thanks are also due to an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rolf H. Bremmer Jr

Rolf Bremmer is emeritus Professor of English Philology at the Leiden University and of Frisian Language and Literature by special appointment of the Fryske Akademy.

Notes

1 All translations in this paper are mine, unless otherwise stated.

2 The following enumeration is fairly complete: Mone (Citation1838); Dirks (Citation1849); Hewett (Citation1879); Siebs (Citation1901); Krogmann (Citation1958; Citation1960; Citation1971); Markey (Citation1981: chap. 2.1 “The Emergence of Frisian as a Literary Language”) (quite uneven in quality); O’Donnell, (Citation1998; innovative); Vries (Citation2004); Di Cesare (Citation2017).

3 The advent of vernacular literacy in medieval Frisia is the subject of Bremmer (Citation2004); cf. Mostert (Citation2010). For Lower Germany: Eastphalia (first half 13C), Northern Germany (middle 13C) and Westphalia (end 13C), see Peters (Citation2001); Peters (Citation2003); Peters (Citation2004).

4 A point partially addressed by Mostert (Citation2021).

5 Budapest, Országos Széchényi Könyvtár (National Library), C 111. The leaf survived as a cover for a late fifteenth-century Middle Dutch/Low German book of hours written in a convent of the Sisters of the Order of St John in Warffum (Hunsingo) in 1505, now Budapest, OSK, Cod. Holl. 6; see Hermans (Citation1988: 74, no. 32).

6 Ghent, MS 3 (interlinear glosses dated to c. 1100–1125; private collection), on which see Langbroek (Citation2015; Citation2017). Groningen, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Hs 404 (interverbal glosses, c. 1200), on which see Langbroek (Citation1990); Bremmer (Citation2007); Lendinara (Citation2014).

7 For the use of either Latin or Frisian for pragmatic texts, see Popkema (Citation2014).

8 For a concise survey of these manuscripts or of early modern, antiquarian copies of manuscripts now lost, see Johnston (Citation2001); Bremmer (Citation2009: §§13–14).

9 For a detailed study of the Frisian registers of compensation, see Nijdam (Citation2008; Citation2013).

10 Extensively surveyed and discussed in Popkema (Citation2007).

11 Curses: notably in the Fia-eth, see Buma & Ebel (Citation1967: text B I.7 and 10); Buma & Ebel (Citation1963: text XII.2a); cf. Bremmer (Citation2010: 543). Incantation: Buma & Ebel (Citation1967: text A VII.159); cf. Nijdam (Citation2001). It concerns a charm against bleeding, widely spread through Western and Northern Europe. To Nijdam’s references add: Forbes (Citation1971: 300).

12 The text has been transmitted five times, see Johnston (Citation2001: 582, no. 19).

13 See the survey in Bremmer (Citation2009: 15, Table 1 [no. 17]).

14 For a discussion of Grimm’s article in the context of its time, see, e.g., Beebee (Citation2012: 58–61).

15 The classic treatment is Bowra (Citation1949). On Grimm and the Romantic Movement, see, e.g., Bisztray (Citation2002); Leerssen (Citation2004).

16 On Old Frisian eternity formulas, see Vries (Citation1986); Bremmer (Citation2019b: 1–4).

17 For a similar opinion – ‘de ereprijs’ [the prize of honor] – in an excursus on Old Frisian literature, see van Oostrom (Citation2006: 69–74).

18 The same approach is taken in Corporaal (Citation2018), a condensed English version of Oppewal et al. (Citation2006).

19 For a similar approach in reconstructing poetry from Old Frisian legal prose, see Baesecke (Citation1943).

20 Evidently a loan translation of ‘Dominus noster’. Remarkable for its fixity, Drohten ‘Lord’ and its synonym Hera, whenever referring to the Lord God or Christ, never appear without the possessive pronoun in Old Frisian texts; see Bremmer (Citation2010: 540).

21 For the combination of ‘hot’ with ‘hunger’ in Old and Middle English, see Deskis (Citation2016: 30–31).

22 The metaphorical association of ‘iron’ with ‘cold’ (i.e., ‘hostile’) was commonplace, in English and Norse, usually in connection with weapons, cf. Salmon (Citation1959: 316–317); in Middle Dutch ‘mijn yser cout’ (i.e., my spear), in Ferguut (Rombauts et al. Citation1994: 106, l. 1825).

23 The combination is also attested for early Middle High German, see Deutsches Wörterbuch online, s.v. Glatt, adj. D, and Middle Dutch, see Middelnederlandsch Woordenboek online, s.v. glat 1.

24 For the widespread notion of the world being beautiful, cf. Middle Dutch ‘scone werelt’: Dirk van Delf (c. 1365–1404), Tafel van den kersten ghelove (Daniëls Citation1937–1939: 2: 139, l. 212; 3: 667, l. 169); Middle Low German ‘schone werlt’ (1445): ‘Spieghel der leyen’ (Roolfs Citation2005: 208, l. 54); Middle English ‘fayre world’: Geoffrey Chaucer, Legend of Good Women (Benson Citation2008: 624: l. 2229).

25 On this combination in various early Germanic languages, see Anderson (Citation2003: 132–136).

26 ‘White silver’ frequently occurs alongside ‘red gold’ in Old English, see DOE online (Cameron et al. Citation2018), s.v. hwit, adj. 7g.

27 On OE grene lond, see Kabir (Citation2001: 143).

28 Cf. OE weallende wæter in Ælfric’s Lives of Saints (Skeat Citation1881–1900: 424, l. 398).

29 For English, see, e.g., Boers (Citation2014: 196–198).

30 Instead of ‘vnder eke and vnder der molde’, some redactions of the three urgencies read the alliterative collocation ‘vnder eke and vnder eerthe’, so Buma & Ebel (Citation1967: text VIII. 20). The collocation of ‘oak’ and ‘earth’ is also found in elegiac contexts in Old English and Old Norse, see Deskis (Citation2020: 386–388).

31 The three urgencies recently received a separate trilingual edition (in Old Frisian, with Modern Frisian and Modern Dutch translations), augmented with thirteen poems and five short stories inspired by the fatherless child (Vries et al. Citation2010).

32 Borchling (Citation1908: 43) ‘Aber nirgends tritt eine solche Innigkeit und Tiefe der Empfindung hinzu, wie in dem köstlichsten Schmuckstücke der friesischen Rechtspoesie’.

33 After all: ‘Colorless personalities cannot survive oral mnemonics’, thus Ong (Citation2002: 69).

34 On this text, see extensively Giliberto (Citation2007).

35 Buma & Ebel (Citation1963: 19): ‘Überhaupt nichts mit einem Rechtscodex zu tun hat […] das Stück über “Die fünfzehn Zeichen vor dem Jüngsten Gericht”’.

36 Buma & Ebel (Citation1969: 15): ‘… diejenigen Stücke der Hunsingoer (und anderen) Handschriften, die, geistlichen oder gar sagenhaften Gegenstandes, nur sehr mittelbar dem Rechtsleben zugute kamen’.

37 As argued for similar features in Irish law, see Qiu (Citation2021: 134–135).

38 Paragraph 21 is also found almost verbatim as the last paragraph of a collection of miscellaneous stipulations involving wergild, headed by the rubric ‘fon daddel’ [about homicide] in a later, fifteenth-century manuscript originating from the neighbouring land of Fivelgo, see Buma & Ebel (Citation1972: text XIII.7). Apparently such short texts were like building blocks, easily taken from one list of stipulations into another.

39 E.g., Phillpots (Citation1913: 151–154) discusses the Frisian wergild tradition in relation to other such Germanic traditions. The sequence in the Hunsingo Register of Compensations is not mentioned once in Henstra’s studies of the Frisian wergild-tradition, e.g., Henstra (Citation2000; Citation2006).

40 Compounded of gēr ‘spear’ and ieve ‘gift’. The patrilateral relatives were often indicated with a weapon–the spear- or sword-side; the matrilateral relatives with a tool associated with women–the spindle- or distaff-side; see, e.g., Deutsches Wörterbuch online, s.v. spindel 1g; Lévi-Strauss (Citation1969: 472).

41 On the intimate relationship between a mother’s brother and his sister’s son, see Bremmer (Citation1980).

42 Cf. Wormald (Citation1999b: 39): ‘To deny the Germanic origin of feud-centred law verges on perversity’.

43 As argued in Bremmer (Citation2010).

44 The phrase an thiaves lestum (in the footsteps of a thief, i.e., as a thief) can be compared with Old English bryde laste (in a bride’s footstep, as a bride), idese laste (in the footsteps of a lady, as a lady), Genesis A, ll. 2716 and 2249, respectively (Krapp Citation1931), and wræccan lastum (in the footsteps of an exile, as an exile), Seafarer, l. 16 (Krapp & Dobbie Citation1936).

45 For other examples of this narrative device in Old Frisian texts, see Bremmer (Citation2014: 22–23), with references to secondary literature.

46 See, e.g., the contributions to Cohen (Citation1979); Borsa et al. (Citation2015); with a focus on Britain: Zacher (Citation2014).

47 Oxford English Dictionary online, s.v. literature 3b.

48 E.g., Buma & Ebel (Citation1963: text III.10): ‘Nu skilu wi Frisa halda usera aldera kest and kera’ [Now we Frisians must keep the statutes and regulations of our ancestors].

49 On the prominent place of the Decalogue in the leges barbarorum, see Wormald (Citation1999a: 31–34).

50 See, too, Cataldi (Citation2022). On the term and nature of Autentica Riocht, see Gerbenzon (Citation1956: 135–143).

51 On textual communities in Frisia, see Bremmer (Citation2021).

52 Buma & Ebel (Citation1969: 16): ‘obwohl sie kaum zu unseren Rechtskenntnisquellen zu rechnen sind, vielmehr zur volkstümlichen Literatur gehören’. The riddles are text V in their edition.

53 Bremmer (Citation2018). The Anglo-Saxon laws, on the other hand, feature only a handful of proverbs, see Bremmer (Citation2019a).

54 As is also borne out by Frisian scribes in diplomatic and scribal practices, see Bremmer (Citation2015). For the international aspect of the Old Frisian incantation against bleeding, see note 11 above.

References

- Abrams, M. H. 1985. A glossary of literary terms. 6th edn. Fort Worth: Wadsworth Publishing.

- Alford, John A. 1977. Literature and law in medieval England. PMLA 92(5), 941–951.

- Algra, N. E. 1998. The relation between Frisia and the Empire from 800–1500 in the light of the Eighth of the Seventeen Statutes. In Bremmer, Johnston & Vries (eds.), 1–79.

- Anderson, Earl R. 2003. Folk-taxonomies in early English. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

- Baesecke, Georg. 1943. Die altfriesischen Gesetze und die Entwicklung der friesisch-deutschen Stabverskunst. Deutsche Vierteljahrschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte 21, 1–22; repr. in his Kleine metrische Schriften. Nebst ausgewählten Stücken seines Briefwechsels mit Andreas Heusler, ed. Werner Schröder, 188–206. Munich: Fink, 1968.

- Beebee, Thomas O. 2012. Citation and precedent: Conjunctions and disjunctions of German law and literature. London: Bloomsbury.

- Benson, Larry D. (ed.). 2008. Geoffrey Chaucer, The Riverside Chaucer. 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bisztray, George. 2002. Awakening peripheries: The Romantic redefinition of myth and folklore. In Angela Estherhammer (ed.), Romantic poetry, vol. 7, 225–48. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Boers, Frank. 2014. Idioms and phraseology. In Jeannette Littlemore & John R. Taylor (eds.), The Bloomsbury companion to cognitive linguistics, 185–201. London: Bloomsbury.

- Borchling, Conrad. 1908. Poesie und Humor im friesischen Recht. Aurich: D. Friemann.

- Borsa, Paolo et al. 2015. What is medieval European literature? Interfaces: A Journal of Medieval European Literatures 1, 7–24.

- Bowra, Cecil M. 1949. The Romantic imagination. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 1980. The importance of kinship: Uncles and nephews in Beowulf. Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 15, 21–38.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2004. ‘Hir is eskriven’. Lezen en schrijven in de Friese landen rond 1300. Hilversum: Verloren.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2007. Footprints of monastic instruction: A Latin psalter with interverbal Old Frisian glosses. In Sarah Larratt Keefer & Rolf H. Bremmer Jr (eds.), Signs on the edge: Space, text and margin in medieval manuscripts, 203–233. Leuven: Peeters.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2009. An introduction to Old Frisian: History, grammar, reader, glossary. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2010. From alien to familiar: Christ in language and law of medieval Frisia. In Jitse Dijkstra, Justin Kroesen & Yme Kuiper (eds.), Myths, martyrs and modernity: Studies in the history of religions in honour of Jan N. Bremmer, 531–552. Leiden: Brill.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2011. Dealing dooms: Alliteration in the Old Frisian laws. In Jonathan Roper (ed.), Alliteration in culture, 74–92. Basingstoke: PalgraveMacMillan.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2014. The orality of Old Frisian law texts. In Bremmer, Laker & Vries (eds.), Directions, 1–48.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2015. Isolation or network: Arengas and colophon verse in Frisian manuscripts around 1300. In Aidan Conti, Orietta Da Rold & Philip Shaw (eds.), Writing Europe, 500–1450: Texts and contexts, 83–100. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2018. ‘The fleeing foot is the confessing hand’: Proverbs in the Old Frisian laws. In Marina Cometta et al. (eds.), La tradizione gnomica nelle letterature germaniche medievali, 70–100. Milan: di/segni.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2019a. ‘Qui brecht ungewaldes, betan gewaldes’: Proverbs in the Anglo-Saxon laws. In Stefan Jurasinski & Andrew Rabin (eds.), Languages of the law in early medieval England: Essays in memory of Lisi Oliver, 179–92. Leuven: Peeters.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2019b. The mysterious dog in two Old Frisian eternity formulas. Us Wurk 68, 1–12.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2020. Thi Wilde Witsing: Vikings as otherness in the Old Frisian laws. Journal of English and Germanic Philology 119(1), 1–16.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H. 2021. More than language: Law and textual communities in medieval Frisia. In Thom Gobbitt (ed.), Law, book, culture in the Middle Ages, 98–125. Leiden: Brill.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H., Geart van der Meer & Oebele Vries (eds.). 1990. Aspects of Old Frisian philology (Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 31–32). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H., Thomas S., B. Johnston & Oebele Vries (eds.). 1998. Approaches to Old Frisian philology (Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 49). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H., Stephen Laker & Oebele Vries (eds.). 2007. Advances in Old Frisian philology (Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 64). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Bremmer Jr, Rolf H., Stephen Laker & Oebele Vries (eds.). 2014. Directions for Old Frisian philology (Amsterdamer Beiträge zur älteren Germanistik 73). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Brennan, Roland. 2019. Conditional sentences in the Old East Frisian Brokmonna Bref. NOWELE 72(1), 11–41.

- Brouwer, Jelle (ed.). 1941. Thet Autentica Riocht: Met inleiding, glossen, commentaar en woordenlijst. Assen: van Gorcum.

- Buma, Wybren Jan. 1949. Die Brokmer Rechtshandschriften. The Hague: M. Nijhoff.

- Buma, Wybren Jan. 1961. De Eerste Riustringer Codex. The Hague: M. Nijhoff.

- Buma, Wybren Jan & Wilhelm Ebel (eds. & trans.). 1963. Das Rüstringer Recht. Göttingen: Musterschmidt.