ABSTRACT

Cross-linguistically, spatial expressions display a propensity to undergo semantic extensions, thus frequently giving rise to grammatical markers. Drawing on diachronic material derived from the Corpus of Historical American English and synchronic data extracted from the Corpus of Contemporary American English, this study reports on a hitherto unexplored, incipient change of this kind, namely that affecting the multiword string a/one step away from. It is shown that with the conventionalization of the invited inference of closeness, the construction at issue was reanalyzed as a complex preposition, functioning initially as an exponent of prospective aspect, then additionally as a similitude marker, and finally also as an approximator. This chronology further finds reflection in the current functional gradience of a/one step away from, in that among its grammatical instances, which amount to slightly more than half the tokens in the sample, aspectual uses constitute the largest proportion, followed by similative occurrences and degree modifier attestations. At the distributional level, the investigated case of grammaticalization manifests itself in the highly confined determination and modification patterns of the form step, counterbalanced by the entire expression’s compatibility with inanimate subjects as well as host-class expansion to abstract NPs, verbal gerunds, and adjectives.

1. Introduction

Spatial expressions have been cross-linguistically recognized to display a strong propensity to undergo metaphorization, thus frequently developing grammatical meanings (cf. Moore Citation2014). As regards the history of English, a commonly invoked example of the pertinent change is the emergence of the futurate be going to-construction, as in It’s going to rain, from a sequence of words denoting directional movement (cf. Sweetser Citation1988; Budts & Petré Citation2016). Further relevant phenomena include the development of a verbal progressive function in the originally spatial expression on one’s/the way to, as in They’re on their way to stardom (cf. Petré et al. Citation2012), as well as the transition of the word-sequence far from into a minimizer, as in That’s far from certain (cf. Brinton & Inoue Citation2020).

This study seeks to report on yet another, relatively recent and hitherto unexplored change similar to those mentioned above, namely that affecting the multiword string a/one step away from, which originally comprises an NP composed of a determiner and the noun step functioning as a measure modifier of the adverb away taking a PP-complement headed by from,Footnote1 and whose lexical semantics implies a small distance in physical space (cf. (1)). Based on diachronic and synchronic data extracted from two balanced corpora, namely the 475-million-word Corpus of Historical American English (henceforth also COHA, for short), which covers the decades from the 1820s to the 2010s, and the one-billion-word Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), it will be argued that for more than half a century now, the construction at issue, while exhibiting a large proportion of lexical metaphorical uses (cf. (2)),Footnote2 has been undergoing grammaticalization into an aspectual exponent, more precisely, an exponent of prospective, also known as proximative, aspect (cf. (3)), a similative marker (cf. (4)), as well as a degree modifier, more specifically, an approximator (cf. (5)).

(1) Ram was thirty. He lived in a perfect house on Hill Street, only a step away from Berkeley Square, a house decorated by David Hicks in severe bachelor sumptuousness. (COHA, 1980)

(2) She felt a chill. She had supposed it an understood matter that she completely filled his life, his capacity for joy. Was that not the basis for marriage? She thought to herself that this was the traditional first step away from the honeymoon glamour. (COHA, 1930)

(3) The money is a reaffirmation of our agreement: I will not report to the State Department the secret that would surely end her career when she is just a step away from becoming an ambassador. (COHA, 2010)

(4) But when you’re not playing for your employer, it’s a different story. And then because of Christoph’s desire to conduct and record and tour, the Symphony told me that they’d only be able to do four of the seven or eight productions in the season. And that’s when things began to deteriorate. It was not a good time economically in Houston in the early ‘90s, and a lot of the freelance players that we called upon just couldn’t cobble together a living, so they would drift away. It was one step away from a pickup band. (COHA, 2006)

(5) And, lastly, there’s Olivia, who is trying so hard to be normal. To live a normal life, with a man who fits into it. Edison shows up at her apartment, with all the making of a romantic in-home date. Alcohol, food, and movies. He is all smiles and charm. He keeps talking. Olivia’s silent, her face one step away from broken. (COCA, 2012)

In consonance with the foregoing, the pursued inquiry aims to achieve three main goals, i.e. (i) to determine the chronology of emergence of particular types of attestations of a/one step away from, (ii) to establish the expression’s current functional gradience, and (iii) to provide a distributional characterization of each kind of use.

The paper is organized in the following way. Section 2 sets the scene for the empirical examination of novel English data by offering an account of the relevant theoretical notions, particularly those derived from grammaticalization theory, with a focus on the development of spatial expressions, including a/one step away from, into grammatical markers. Section 3 describes the method employed in the study, while Section 4 presents the results of the analysis. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the main conclusions reached in the investigation, at the same time outlining prospects for future research on the topic.

2. Theoretical background

According to Kuryłowicz’s (Citation1965: 69) oft-cited definition, grammaticalization involves ‘an increase of the range of a morpheme advancing from a lexical to a grammatical or from a less grammatical to a more grammatical status’. However, it is actually not only single morphemes, but also larger expressions, that may undergo grammaticalization, as evidenced by all of the previously mentioned examples, including the multiword string a/one step away from.Footnote3 Linked to this observation is the fact that the discussed type of language change is invariably ‘fostered in constructional straitjackets’ (Paradis Citation2008: 336), i.e. a form, or a series of forms, undergoes grammaticalization within specific syntagmatic environments, rather than in isolation (Bybee et al. Citation1994: 11; Croft Citation2001: 261; Traugott Citation2003; Himmelmann Citation2004; Brinton & Traugott Citation2005: 95). As will be shown in Section 4, a/one step away from grammaticalizes in predicative contexts, following copula verbs such as be or seem.

Crucially, the shift towards a grammatical function is licensed by the emergence of a more abstract, procedural meaning in the relevant expression, a change driven by pragmatic inferencing (Heine et al. Citation1991: 103; Evans & Wilkins Citation2000: 550; Hopper & Traugott Citation2003: 82). Thus, a grammaticalization process begins with a semantic generalization of the pertinent unit, attendant upon its loss of discourse prominence (Boye & Harder Citation2012: 7). In other words, the descriptive content of a grammaticalizing expression becomes backgrounded to the benefit of more schematic implications (Sweetser Citation1988: 392; Hopper & Traugott Citation2003: 94).Footnote4 For instance, directional motion verbs, i.e. those denoting purposive movement, tend to be reinterpreted as pointing to the occurrence of future events, thus acquiring the grammatical function of futurity markers (Traugott & Trousdale Citation2013: 219), as exemplified by the English be going to-construction. In a similar vein, the grammaticalization of a/one step away from will be shown to have been enabled by the conventionalization of the closeness inference, originally arising in space-related uses, foregrounded by a frequent employment of reinforcing elements, such as just and only.

In fact, the inference-driven development may oftentimes be argued to ultimately stem from metaphorization (Bybee & Pagliuca Citation1985: 75), whereby a more abstract notion is understood in terms of a more concrete one (cf. Lakoff & Johnson Citation1980). Indeed, Heine et al. (Citation1991: 160), based on a large body of evidence from language change, propose a metaphor-based hierarchy of abstractness relative to which expressions representative of the more tangible, physical concept of SPACE display a cross-linguistic propensity to evolve into temporal and/or quality markers (cf. (6)).

(6) PERSON > OBJECT > PROCESS > SPACE > TIME > QUALITY

As for a/one step away from, the metaphorical development was actually enabled by metonymy,Footnote5 in that the meaning concerned with the event of taking a step was extended to the distance covered by performing such an action. Equally significant as regards the semantic dimension of grammaticalization is the tendency for grammaticalizing expressions to undergo subjectification, so that they start to mirror a more speaker-centered view (Traugott Citation1989: 34–35; Citation2010: 30; Traugott & Dasher Citation2002: 225). By way of illustration, the English be going to-construction can be employed to convey predictions based on the speaker’s opinion (cf. Budts & Petré Citation2016). Likewise, a/one step away from will be claimed to display an epistemic coloring in some of its uses, reflective of the speaker’s assessment pertaining to the level of probability that a particular event will occur.

Importantly, the above-discussed changes in meaning are accompanied by the decategorialization of the grammaticalizing expression, whereby it loses features typical of its original syntactic category (cf. Hopper Citation1991), and which leads to its formal reanalysis. Be going to, for instance, was syntactically reanalyzed as an auxiliary. A/one step away from, in turn, will be argued to have become a complex preposition, with the element step having given up most of its nominal qualities, including referentiality and the concomitant availability of practically unconstrained determination and modification patterns. Being covert, however, syntactic reanalysis ‘does not involve any immediate or intrinsic modification of its surface manifestation’ (Langacker Citation1977: 58). Even so, it does not in fact happen ‘out of the blue’, and instead occurs in relation to ‘a concrete syntagmatic environment within which a certain linguistic item can be interpreted as belonging to a position differing from its erstwhile positional properties’ (Bisang & Wiemer Citation2004: 9), thus ‘involv[ing] new structural configurations for old material’ (Traugott Citation2008: 225).

It is only later that the aforementioned syntactic change manifests itself in the extended distribution of the reanalyzed unit, labelled by Himmelmann (Citation2004) as host-class expansion and syntactic context expansion. As for the former phenomenon, be going to was certain to have undergone syntactic reanalysis once it started to combine with verbs incompatible with the purposive motion frame, such as stative psychological predicates. What may be taken to instantiate the latter change, on the other hand, is the construction’s compatibility with abstract subjects (Bybee Citation2003: 147; Traugott Citation2011: 25). Similarly, the host-class expansion of a/one step away from finds reflection in the expression’s regular co-occurrence with abstract nominals invoking eventualities/qualities, verbal gerunds, as well as adjectives, while its syntactic expansion consists in the associated copula verb permitting inanimate subjects. Considering a higher number of settings in which a grammaticalizing expression may occur, it further stands to reason that grammaticalization leads to a general increase in the frequency of use of the relevant unit (Traugott Citation2011: 28).Footnote6

Being gradual, grammaticalization, although diachronic in nature, has a synchronic aspect to it, known as gradience (cf. Traugott & Trousdale Citation2010), which means that grammaticalizing expressions synchronically display a layering of grammatical functions (Hopper & Traugott Citation2003: 122). As stated before, the string a/one step away from has been found to have developed an aspectual (more precisely, prospective), a similative, and a degree modifier (more precisely, approximator) function. The very notion of aspect captures ‘different ways of representing the internal temporal constitution of a situation’ (Comrie Citation1976: 52), with prospective, or proximative, aspect pertaining to ‘a temporal phase located close to the initial boundary of the situation’ (Heine Citation1994: 36), and hence signaling ‘an imminently future state’ (Comrie Citation1976: 64). Similitude marking, by contrast, concerns a meaning which

lies somewhere half way between the ‘same’ and ‘different’ poles of the continuum, and this is reflected in the range of expressions involved, which sometimes suggest a closer affinity with the former pole (‘almost the same as’) and sometimes are quite different (‘not really the same as’) (Fortescue Citation2010: 127).

Needless to say, in its similative uses, a/one step away from instantiates the former of the above-mentioned cases. Degree modifiers, in turn, are employed to ‘specify a degree of some property of the element they apply to’ (Paradis Citation1997: 14), i.e. to ‘mark that the extent or degree is either greater or less than usual or than that of something else in the neighboring discourse’ (Biber et al. Citation1999: 554), with approximators communicating that the subject barely fails to reach the degree invoked by the associated predicate, thus ‘imply[ing] a denial of the truth value of what [the predicate] denote[s]’ (Quirk et al. Citation1985: 599).

What all prospective markers, similative expressions, and approximators have in common, though, is an inherently scalar meaning. With respect to scalarity, the aspectual uses of a/one step away from on the one hand and its similative along with degree modifier uses on the other can be conceptualized as indicating, respectively, a point on a temporal scale which slightly precedes the moment when an event occurs or a state starts to hold, or a point on a qualitative scale lying a bit before the reference value. Nevertheless, whereas similative markers externally impose a differential scale and locate two entities close to each other, degree modifiers rely on a scale introduced by the associated gradable element.

3. Method

As already stated in the Introduction, the empirical investigation into the grammaticalization of the expression a/one step away from pursued here encompasses a diachronic study complemented with a synchronic analysis. The diachronic data were extracted from the Corpus of Historical American English (COHA), while the synchronic material was derived from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). In both cases, I employed the command step_n away from, which required that the item step be nominal, at the same time imposing no constraints on its determination and modification patterns.

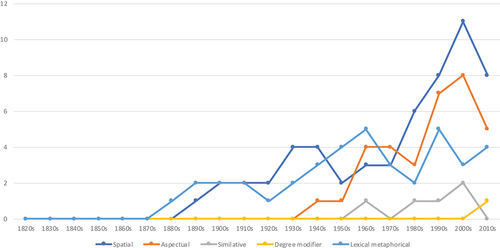

The next stage of the diachronic study involved a removal of seven irrelevant attestations of the string step away from, namely one doublet, one unanalyzable token,Footnote7 and five instances where the form step was actually a verb wrongly tagged as a noun. Based on the remaining attestations, two graphs were constructed, one of which shows the frequency of all relevant tokens over time, and the other specifies the chronology of emergence of particular types of uses, i.e. spatial, lexical metaphorical, aspectual, similative, and degree modifier.

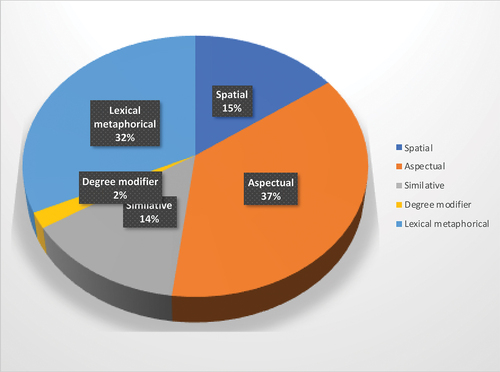

While the diachronic analysis is grounded on exhaustive data, the synchronic one builds on a corpus-generated random sample composed of 200 pertinent attestations.Footnote8 As was the case with the examination of historical material, the initial phase of the synchronic analysis consisted in a filtering out of 23 irrelevant examples (16 instances of verbal step being wrongly tagged as a noun together with 7 repetitions), which were later replaced with the same number of randomly selected pertinent tokens taken from another corpus-generated sample. The relevant uses thus obtained were then classified into the above-listed five categories, which enabled the creation of a pie chart demonstrating the synchronic functional gradience of the expression under scrutiny.

The subsequent parts of the paper present the results of the diachronic analysis and of the complementary synchronic study, respectively. Throughout the text, additional qualitative comments are offered, and each observation is illustrated with authentic examples.

4. Results

4.1. Diachronic analysis

presents changes in the frequency of the word-string step away from over time, as evidenced by the COHA material.

As can easily be noted, the frequency of the analyzed word-sequence has risen considerably, albeit not steadily, from a mere 29 occurrences in the years 1880–1949 to as many as 104 in the years 1950–2019, which already suggests an ongoing change. Indeed, reveals that the first grammatical uses of step away from date back to around the middle of the 20th century.

Interestingly, the earliest attestation of step away from in the material is already metaphorical, with the first spatial uses emerging a bit later. As regards its grammaticalization patterns, step away from first developed aspectual uses, and then similative ones. Finally, the diachronic material reveals one relatively recent degree modifier attestation.

In what follows, I discuss particular types of uses of the analyzed expression in an order reflective of the chronology of their development, i.e. lexical metaphorical, spatial, aspectual, similative, and degree modifier. In particular, I pay attention to the distributional specificity of each type, simultaneously trying to identify possible bridging contexts in the grammaticalization process under examination.

4.1.1. Lexical metaphorical

As stated before, the first attestation of step away from in the historical material, dating back to the 1880s, already exhibits a metaphorical character, yet rather than constituting evidence for an incipient grammaticalization change, it refers to an action performed with the aim of retreating from what the nominal complement stands for (cf. (7)). Thus, the item step retains its nominal status here, as additionally evidenced by its co-occurrence with the definite article as well as the ordinal numeral first, and it may be replaced with abstract nouns such as deviation or departure.

(7) On the whole, in speaking of these patterns I shall be thinking of those that necessarily recur; designs which have to be carried out by more or less mechanical appliances, such as the printing block or the loom. Since we have been considering colour lately, we had better take that side first, though I know it will be difficult to separate the consideration of it from that of the other necessary qualifications of design. The first step away from monochrome is breaking the ground by putting a pattern on it of the same colour, but of a lighter or darker shade, the first being the best and most natural way. (COHA, 1882)

A vast majority of the subsequent attestations representative of the discussed type likewise instantiate the departure sense invoked by step away from, in which case the noun step, apart from combining with the definite article (cf. (8)), may be modified by a variety of qualitative adjectives (cf. (8)–(12)) as well as can be anaphorically referred to by means of a pronoun (cf. (8)). Importantly, given the fact that in such cases, the metaphorical departure tends to be portrayed as large rather than small, coupled with the discourse prominence of the nominal item step, attestations of this sort cannot be seen as potential bridging contexts in the grammaticalization change of interest here.

(8) The way to non-partisan election of judges is hard. Chicago voters will be unable to vote blindly for Municipal Court judges by merely making a mark to indicate whether they prefer Wilson or Hughes. They will have to make a mark on a separate ballot if they wish to vote for judges. But as that ballot also is arranged in party columns, the step away from partisanship is not a very long one. (COHA, 1916)

(9) The Rykov bill of last week could be regarded in one of two lights. It was drawn as an amendment to the Soviet Constitution and it proposed to grant the Russian people the right to practice religion freely. At face value, this seemed a tremendous step away from the Redness of the Founding Fathers. (COHA, 1929)

(10) Their new course is a long step away from the usual N. A. A. C. P. policy, which has believed that enlisting the aid of influential whites was the key to the advancement of the Negro. (COHA, 1947)

(11) The program is wise, realistic, and far sighted. Most certainly it is a courageous, refreshing, and long needed step away from the philosophy of public subsidy of private interests. (COHA, 1955)

(12) Coleman is the one whose work still remains somewhat ‘controversial’ in the fan and trade press. And this is natural, for his music takes the biggest step away from established convention into a real renewal of jazz. (COHA, 1961)

Despite the impossibility of taking the above metaphorical uses to fuel the emergence of grammatical occurrences of step away from, the analyzed material reveals one figurative attestation which builds on an extended spatial metaphor, whereby hate and love are depicted as two objects located very close to each other, at the same time generating the temporal inference that it does not take much time for one to progress from one state to the other, an interpretation strengthened by the use of the noun lull, denoting a short calm interval (cf. (13)). Notably, the closeness implications are additionally foregrounded by means of the adverb just. The hypothesis according to which (13), dating back to the 1930s, constitutes a possible bridging context in the development of aspectual uses is further substantiated by the fact that the earliest grammatical attestation of step away from in the scrutinized data represents the ensuing decade, i.e. 1940s. Equally important here is the finding that, as will be shown in Sections 4.1.3–4.1.5, the grammatical attestations of the scrutinized expression display a very strong tendency to involve reinforcing elements, including just.

(13) You know, psychiatrists say hate’s just a step away from love. Yeah, but it’s the lull in between that drives you crazy. (COHA, 1938)

The conventionalization of the closeness inference is evidenced by yet another metaphorical attestation similar to the one above, namely (14), again involving the emphasizer just. That (14) likewise draws on a creative spatial metaphor is reflected in the use of the stative posture verb lie.

(14) It is typical of Author Moravia that conjugal hell lies just a step away from marital contentment. (COHA, 1955)

4.1.2. Spatial

The 1890s data reveal the first spatial attestation of the analyzed word-string, in which a tidy step refers to a considerable distance (cf. (15)). Notably, despite obviously not giving rise to the closeness inference, the phrase in question may be assumed to function as a modifier of the adverb away, so that the nominal character of step is backgrounded.

(15) Nix Nought Nothing took her comb from her hair and threw it down, and out of every one of its prongs there sprung up a fine thick briar in the way of the giant. You may be sure it took him a long time to work his way through the briar bush and by the time he was well through Nix Nought Nothing and his sweetheart had run on a tidy step away from him. (COHA, 1898)

The subsequent spatial attestations of the expression step away from involving movement can be broadly divided into two kinds. In one of the categories, the item step, referring to a minimal walking event, is discursively primary by virtue of retaining its nominal characteristics, such as compatibility with quantifiers (cf. (16)), the capability of functioning as the direct object of a verb (cf. (17)–(18)), as well as the possibility of participating in ellipsis (cf. (16)). The other class, by contrast, encompasses attestations where a step may be analyzed as a measure modifier equivalent to a bit or slightly, in which case its nouniness is backgrounded (cf. a step was taken away from X vs. *a step was moved away from X; *a step was drawn away from X), and which can therefore be assumed to facilitate the grammaticalization change under scrutiny.

(16) He had never dreamed of the force of his attachment to this dear place, and he turned his face toward the old gray house again and again. Every step away from it seemed more difficult than the last, and his feet became heavy as lead. (COHA, 1900)

(17) He was still good-humored. ‘Look at your hands; it gives me goose-flesh when you touch me.’ ‘Cuttin’ down trees, diggin’, lookin’ after horses don’t leave them very white and smooth.’ ‘Let me go! Let me go!’ He took a step away from the door. His whole manner changed. (COHA, 1914)

(18) SID HUNT I cain't account fer him flarin’ up like he did no other way. Has he ever said anything to you about evenin’ up the score between the Hunts an’ Lowries? (She starts and takes a step away from him with instinctive distrust.) You needn’t be afraid to tell me! JUDE LOWRY I ain’t afraid to tell nobody the truth! (With suppressed emotion.) (COHA, 1923)

(19) Marteau looked about him, moved a step away from the sentries and the corporal and sergeant of the guard, and whispered a word into the ear of the officer. (COHA, 1915)

(20) Slowly the girl’s eyes had widened, as if she saw that new-born thing riding over all other things in his swiftly beating heart. And afraid of it, she drew a step away from him. (COHA, 1921)

(21) ‘Do you promise, Ernest Leonard?’ ‘I promise, Miss Bellamy,’ he said and moved a step away from her. (COHA, 1947)

Notably, cases such as (17)–(21) metonymically allow a resultative stative inference pertaining to (short) distance, in that the action of both taking a step away from X and moving/drawing a step away from X entails being at a step’s distance from X, which, in turn, permits the more subjective interpretation of being ‘close to X’, as already illustrated by the spatial metaphors in (13) and (14). Also noteworthy here is that the initial stative uses producing the closeness inference date back to the 1930s and the 1940s (cf. (22)–(23)), and thus may be claimed to have paved the way for the emergence of the aspectual meaning, whereby proximity in space is mapped onto that in time.

(22) GAYLORD EASTERBROOK (Backs away a few steps from her. Beyond appeal) You can return to gaze at yourself forever in a full-length mirror! (He turns upstage a step away from her) Oh, God – ! (COHA, 1939)

(23) When she had closed the door Elizabeth was only a step away from the straight visitor’s chair slanting at the desk; she sat down and stretched her feet out in front of her. (COHA, 1949)

As already mentioned, it is not infrequent for the proximity implications to be brought to the fore with the help of reinforces such as only (cf. (23)–(24)) and just (cf. (25)), which, as will be shown in the next section, is also a typical feature of the grammatical uses of step away from, and which hence bears additional witness to the facilitating role of such space-related attestations in the grammaticalization of the discussed expression.

(24) That was why I did not see, until I was only a step away from him, that a man lounged against one side of the open doorway. (COHA, 1974)

(25) But her residence is just a step away from Main Street, on the West Danby road, an even smaller hamlet a few miles over the mountain on a high and forlorn plateau. (COHA, 1972)

4.1.3. Aspectual

As suggested above, it is just the conventionalization of the closeness inference that gave rise to the aspectual uses of step away from, whereby the expression indicates that the subject is close to entering a specific eventuality (cf. (26)–(30)). The earliest aspectual attestation of step away from, however, displays a pronounced degree of conceptual persistence, since it relies on an extended movement metaphor depicting the temporal progression of the subject’s career (cf. (26)). Moreover, (26), like some of the later aspectual occurrences, may be said to carry additional epistemic overtones, in that imminence implies a high degree of certainty that the relevant event will occur, as also suggested by the evidential verb seem.

(26) However real she is gone, Toni Harper is obviously going further. A dreamy, fidgety little girl of ten, Toni is one of Hollywood’s about-to-be-discovered wonders. Columbia Records will shortly release her first two records, and last week she was signed up for a Hollywood musical. # When she patters to the center of a stage, smooths down her dress, poises her small hands like a tiny coffee-colored ballerina, and starts out on a husky, whispery ballad, she seems only a step away from being a Maxine Sullivan or an Ella Fitzgerald. (COHA, 1948)

(27) Somewhat sooner than expected, Fidel Castro last week took over direct control of the Cuban government. Premier Jose Miro Cardona resigned, along with his Cabinet. Assuming the premiership. Castro quit as commander of the armed forces, giving that job to his ice-eyed brother Raul, 27. # The move, said Fidel Castro, ‘distressed’ him, but it was ‘necessary for the good of the revolution.’ It put him only a step away from the presidency, now held by his hand-picked choice, Manuel Urrutia. (COHA, 1959)

(28) ‘Take two people,’ he had said. ‘Two people genetically identical. Damage one of them so badly that he is helpless and useless – to himself and to others. Damage him so badly that he is always only a step away from death.’ (COHA, 1963)

(29) A tall man in a small suit is classically funny. It’s been funny for centuries. And you ought to know. Are you making allusions to my age? If the allusion fits, wear it. You are one step away from making Custer’s Last Stand look like a love-in. (COHA, 1968)

(30) Then he said, ‘But how come you never buy any coffee, and yet always have it on hand?’ She smiled at the question, almost with relief. ‘I guess it’s okay to let the cat out of the bag. Melva and Margaret drink it, too. So, every now and then, when anyone’s in Salt Lake, they pick up one or two cans.’ ‘Well, I’ll be darned,’ Clair grinned. ‘This innocent-lookin’ place is just one step away from bein’ a Chinese opium den.’ (COHA, 1974)

A notable characteristic of the aspectual expression step away from is that when accompanied by a stative predicate, it imposes a dynamic telic interpretation on it. Thus, although be itself is stative, a step away from being in (26) and (30) means about to become,Footnote9 and the same applies to (31), which puts emphasis on a swift transition from one state into another, except that it exhibits a stronger modal colouring, as it lists a set of conditions making such a transition likely to occur. The data further indicate that a causative construal may be externally imposed on the investigated construction by means of the verb put, as in (27), which reveals that the subject was caused to find himself in a situation when he was about to become president, but the telic change-of-state event finally did not happen. Similarly, in (32), the relevant decision led to US policy being on the verge of a calamity, which eventually did not occur.

(31) TOM Everybody’s different! I mean CARTER Come on, be honest! The thing they represent that’s so scary is what we could be, how vulnerable we all are. I mean, any of us. Some wrong gene splice, a bad backflip off the trampoline too many cartons of Oreos! We’re all just one step away from being what frightens us. What we despise. So we despise it when we see it in anybody else. (COHA, 2004)

(32) Though Carter soon denounced the election as ‘totally fraudulent,’ the Carter critic in the delegation said, ‘There is no certainty he would have condemned it if he got into talks with Noriega. The decision to involve Carter put U.S. policy one step away from a calamity.’ (COHA, 1994)

As can be seen, the host-class expansion of the prospective marker step away from manifests itself in its co-occurrence with either verbal gerunds or eventuality-denoting abstract nouns. However, with the entrenchment of the aspectual meaning, which took place around the middle of the 20th century, the temporal expression at issue started to appear alongside concrete nouns, the associated event being retrievable from the context (cf. (33)–(35)).

(33) I’ve had a squad car parked in your driveway all this time. He wouldn’t have called if he was. Where are you going? To my office. This picture, it bothers me. I want to check it out with our files. Uh-uh. Just stretching my legs. Stretch’ em on that side of the room. You sure you could use that gun? Mister, I’m just one step away from $25,000. You’d better believe I’ll use this gun if I have to. (COHA, 1964)

(34) However, if there are budget reasons why the complete system can not go into a new house now, the wise thing is to have the engineering and design phases done. That way, you’ll be ready for simple add-on, later. If you own a house with a ducted warm-air system, you may be only a short step away from CAC: MAY 1970 (COHA, 1970)

(35) She had the sort of pinched face that made a smile look pained and exaggerated. She smelled too strongly of powdery perfume, putting Ahmo in mind of the funeral homes her clients were one step away from. (COHA, 1999)

Another important observation is that in most cases, the aspectual attestations of step away from involve animate (human) subjects, which can be explained with reference to the persistence of the feature of animacy, intrinsic to the original semantics of the noun step. Moreover, the imminence meaning of the investigated expression is usually further reinforced by the use of elements such as only (cf. (26)–(28), (34)), just (cf. (30)–(31), (33)), short (cf. (34)), and one (cf. (29)–(33), (35)), of which the last, by virtue of originally encoding the minimal positive value on a scale of natural numbers, functions here as a kind of emphasizer.Footnote10 Equally noteworthy in this context are the restricted determination and modification possibilities of the largely decategorialized item step, which is only compatible with the indefinite article as well as reinforcers.

4.1.4. Similative

The 1960s data contain the first attestation of step away from in the similative meaning which can be paraphrased as ‘almost the same as X’, ‘very much like X’, ‘very similar to/not very different from X’, ‘qualitatively very close to X’, etc. (cf. (36)–(39)), whereby two entities are compared with each other with respect to an implicit property. Again, similarly to the case with aspectual uses, similative attestations are marked by the employment of elements foregrounding closeness implications, such as only in (36) and (37), just along with one in (38), as well as barely in (39). Besides, the similitude-related occurrences further testify to a high degree of decategorialization of the originally nominal form step, which, no longer being referential, rejects the definite article as well as purely qualitative adjectives.

(36) The Japanese say the Chinese tested missiles with ranges of 450 to 650 miles three years ago. They believe the Chinese are working on satellite launchers with, a 1,200-mile capability, only a step away from the intercontinental missile. (COHA, 1966)

(37) There’s choral singing that’s only a step away from the performances on ‘Mbube’; there’s stark, accordion-driven pop from Lesotho, the independent black-ruled country surrounded by South Africa; there’s sax jive – African funk with saxophone melodies rather than vocals – from the Boyoyo Boys; there’s Zulu pop, with tickling guitars, sliding fiddle riffs and tradititionalist melodies, and there’s the urban, three-chord pop of mbaqanga, with its Westernized four-bar riffs below unmistakably African melodies. (COHA, 1988)

(38) HOLLAND What was that? BOOMP! BOOMP! BOOMP! Somebody is pounding on a piano. HOLLAND Somebody’s fooling around in the gymnasium. IRIS Leave it be, Glen. BOMP! BOMP! HOLLAND No one should be in there. BOMP! BOMP! Holland walks toward the gymnasium. HOLLAND Besides, that piano is just one step away from firewood as it is. (COHA, 1995)

(39) Empirical (though not necessarily experimental) evidence is the only kind of evidence we have in our attempts to understand the workings of the mind and the associated behavior. Empirical evidence is based on experiments or experience. In the hierarchy of scientific inquiry, empirical evidence is barely a step away from pure observation, the foundation of science. (COHA, 2006)

Interestingly, as evidenced by the above examples, the word-sequence step away from in its similative function is typically employed in relation to inanimate, whether concrete (cf. (36), (38)) or abstract, subjects (cf. (37), (39)), which stands in stark contrast to the predilection of the expression’s aspectual uses to involve animate subjects, and which points to its having undergone syntactic context expansion. Likewise, the similative marker step away from may be complemented by concrete (cf. (36), (38)) and abstract nouns (cf. (37), (39)).

It seems that similitude-related attestations such as those cited above have been enabled by the fact that telic events implied by the aspectual uses of step away from oftentimes have qualitative aspects to them. In (26), for instance, the subject already exhibits certain properties of the famous singers, and thus may be said to bear similarity to them. Likewise, in (28), the damage caused to the subject is supposed to lead him to a state reminiscent of that of a dead person.

4.1.5. Degree modifier

In the diachronic material, there is only one, quite recent attestation which can be analyzed as a degree modifier use of step away from, paraphrasable simply as ‘almost X’, namely (40), where the speaker regards the referent’s behavior as bordering on lunacy. Thus, it is possible for only a step away from lunacy in (40) to be paraphrased as ‘almost lunacy’ or ‘almost lunatic’. Analogously to the case with aspectual and similative uses, the discussed example includes the emphasizers only and one, and simultaneously bears witness to the partially decategorialized status of step. In contrast to similative uses, however, degree modifier attestations rely on a scale introduced by the complement itself, which explicitly invokes a gradable bounded quality. Yet, as will be demonstrated in the analysis of synchronic data, the host-class expansion of step away from in its degree modifier occurrences is not limited to abstract nominals such as lunacy, but also involves verbal gerunds and even adjectives.

(40) ‘Did you go to one of those sites like match dot com? Have you met your perfect match? This is so romantic-’ # ‘It is not romantic,’ I said sternly. ‘In fact it might be only one step away from lunacy. What do you know about this man aside from the fact that he owns a computer?’ (COHA, 2016)

4.2. Synchronic analysis

As shown in , the synchronic functional layering of the expression step away from mirrors the chronology of development of particular types of grammatical uses. In other words, among the 106 grammatical instances detected in the sample (N = 200), there are 74 aspectual attestations, 28 similative occurrences, and 4 degree modifier uses.

Moreover, assuming that the synchronic proportion of grammatical attestations of an expression in language practice reflects its current degree of grammaticalization, the relevant value for the word-sequence step away from lies at 53%, which testifies to an incipient character of the analyzed change.

The findings arrived at based on synchronic data largely concur with those made with reference to the diachronic material. First, the lexical metaphorical attestations of step away from typically exploit the departure meaning, in which case the item step retains its nominal characteristics (cf. (41)). Second, the closeness inference invited by step away from tends to be foregrounded by means of reinforcers, which applies to both spatial and grammatical uses of the investigated expression, with step having undergone a substantial level of decategorialization (cf. (42)–(47)). Third, the persistence of the feature of animacy inherent in the lexical make-up of the noun step translates into a strong tendency for the scrutinized expression’s aspectual uses to involve animate subjects (cf. (43)–(46)), although this apparent constraint does in fact not extend to similative and degree modifier attestations (cf. (47)–(50)). Moreover, the aspectual uses, which reveal a modal tinge every now and then, may involve both concrete (cf. (43)) and abstract NPs (cf. (44)) as well as verbal gerunds (cf. (45)–(46)). And additionally, when accompanied by originally stative predicates, the aspectual marker step away from produces a dynamic construal (cf. (46)). Similarly, the employment of the verb put coerces a causative reading (cf. (44)).

(41) On Friday, the Cardinals unveiled new uniforms, a fauxback alternate jersey, and a change in their road caps. The moves were marketed under the false flag of ‘tradition.’ The problem for DeWitt and the franchise is that one of the reasons Cardinals fans are thought to be amongst baseball’s best is our appreciation of and knowledge about the history of the game and our Cardinals. The uniform changes announced on Friday are a dramatic step away from Cardinals tradition, not an embrace of it. (COCA, 2012)

(42) The Windsor Great House was built in the late 18th century, on a site that may have been used by the British as a military base because of its strategic location on the edge of the forbidding terrain of the Cockpit Country. Just a step away from the great house grounds is an old trail that crosses the Cockpit Country. (COCA, 2012)

(43) I fear that if big business is allowed to getting its way we will keep going backwards. By backwards I mean working in an unsafe atmosphere while big business is allowed to pollute the air we breathe. Newt Gingrich even mentions bringing back child labor. We are one step away from sweatshops and kids going back into mines. (COCA, 2012)

(44) The floodgates for non-winners of majors have been flung open by Retief Goosen’s success at the U.S. Open and David Duval’s at the British Open. # Plus, Woods is desperate to lose a third major in a row, which would put him just one step away from the Unslam – losing all four major title defenses in a row. (COCA, 2001)

(45) He is a gifted psychiatrist. Even if I don’t share your godlike worship of him. Well, I simply have a healthy respect for the man, Niles. It’s hardly worship. Oh, please. You’re one step away from seeing his image appear in a tortilla. (COCA, 2001)

(46) I’m well aware that horses are large animals. But the fodder you got is the fodder you got. They can’t continue on under these circumstances. Yes, they can. That’s what whips are for. No! Jimmie, you are one step away from being fired. Get back to the barn. (COCA, 2019)

(47) ‘Storytelling and story acting will be, I am certain, my most widespread and long-lasting influence upon the early childhood classroom,’ Paley told Judith Wells Lindfors of the NCTE in an online conversation about her career. ‘It is but one step away from play itself and encompasses nearly all the fantasy and imaginative power we find in play.’ (COCA, 2005)

The foregoing notwithstanding, the synchronic material makes it possible to provide a better characterization of the similative and degree modifier occurrences of step away from owing to a larger number thereof in the COCA than was the case with the COHA. The former type has turned out to express comparisons drawn between not least two entities, but also two states of affairs or their effects. Such uses involve abstract subjects, frequently pronouns referring anaphorically to clauses, and complements in the form of verbal gerunds (cf. (48)–(50)). Presumably, what lies at the core of such attestations is the modal potential of the expression under analysis, i.e. the speaker’s estimation that some anterior action is logically very likely to be followed by the eventuality designated by the verbal gerund by dint of them being qualitatively very close to each other.

(48) This is not the first time something like this argument has been advanced in this discussion: to me it seems like in various ways some people are arguing against the very notion that poetry, or any other art, should require any elucidation from critics, reviewers, etc. That seems to be just one step away from arguing that we shouldn’t need any education at all! (COCA, 2012)

(49) I use Notepad. It’s one step away from writing it on yellow sticky-notes, but it meets my needs. The only problem is that I can’t access my to-do list while I’m out of the office (at least not easily.) (COCA, 2012)

(50) Many youngsters are eager to escape the ostracism of this breed of alternative ed. ‘A lot of kids and parents see it as one step away from being in jail,’ says Sunshine Sepulveda-Klus, who coordinates alternative-education programs in the Los Angeles Unified School District. (COCA, 2003)

Uses of the latter kind, in turn, have been shown to involve adjectives (cf. (51) as well as (5)) and verbal gerunds which explicitly introduce a gradable component.Footnote11 In other words, rather than indicating an imminent progression from one state into another, both (52) and (53), like (40), convey that the subject barely fails to reach the bounded property encoded by the complement. In (52), the closed-scale qualitative element is provided by the idiomatic phrase scared to death, while in (53), the verb beg implies an extreme value on a scale of intensity pertaining to the act of requesting.Footnote12 Despite the scarcity of the relevant data, it further appears that attestations such as (52), in which an adjective or an AP occurs within a gerundial phrase, functioning as a complement of the copula be, have had a significant role to play in the emergence of ad-adjectival uses, in that attestations such as (5) and (51) may have arisen due to ellipsis of the form being (cf., e.g., a step away from being broken and a step away from broken).

(51) Oh no, I don’t wanna be the crutch One step away from down I don’t wanna be the crutch (COCA, 2001)

(52) Whatever she saw scared her so bad her mind couldn’t deal with it and it shut down. It’s one step away from being scared to death. (COCA, 1993)

(53) I looked at myself in the small mirror in the WC. Short black hair, not a bad bod, just wearing plain paper panties, for with all the dust kicked up in the air, why get everything else filthy? Besides, when done, cleaning me and the WC only took a few minutes with a few judicial sprays of water, emphasis on the word judicial. ‘Eva?’ came the voice, just one step away from begging. (COCA, 2009)

5. Conclusion

Drawing on diachronic material derived from the Corpus of Historical American English complemented with synchronic data extracted from the Corpus of Contemporary American English, this paper sought to provide an account of a previously unexplored, ongoing grammaticalization change, namely that affecting the multiword string a/one step away from. It was argued that with its reanalysis as a complex preposition in predicative settings, attendant upon the conventionalization of the closeness inference invited by its stative space-based uses around the middle of the 20th century, the expression first acquired the function of a prospective aspect exponent, then that of a similitude marker, and finally that of a degree modifier, more specifically, an approximator, the last being a very recent development.

Notably, the above-sketched chronology finds reflection in the synchronic gradience of a/one step away from, in that among its grammatical instances, which amount to slightly more than half the tokens in the sample, aspectual uses make up the largest proportion, followed by similative occurrences and degree modifier attestations. The entire dataset further enables a delineation of the investigated expression’s distributional specificity in particular functions, including the extent of its host-class and syntactic context expansion. As for the aspectual attestations, a/one step away from, while occasionally exhibiting an epistemic coloring, is normally employed in relation to animate (human) subjects, which can be elucidated in terms of the persistence of the feature of animacy intrinsic to the lexical profile of the noun step. Moreover, functioning as an aspectual exponent, a/one step away from can be complemented by concrete NPs invoking eventualities, abstract eventuality-denoting NPs, as well as verbal gerunds. Another noteworthy fact is that when accompanied by originally stative predicates, the prospective marker at issue imposes a dynamic construal on the situation. In addition, the application of the verb put to the analyzed construction may coerce a causative reading. In its similative uses, by contrast, a/one step away from displays a preference for inanimate, whether concrete or abstract, subjects, of which the latter frequently include anaphoric pronouns referring back to clauses. As a rule, the similitude marker under discussion combines with concrete inanimate and abstract NPs as well as verbal gerunds. Although rare, the degree modifier tokens of a/one step away from, in turn, reveal its compatibility with concrete inanimate, concrete animate, as well as abstract subjects, and with abstract complements in the form of nominals invoking a gradable feature, verbal gerunds containing a gradable element, as well as gradable adjectives. What all types of grammatical uses nonetheless have in common is the strong tendency for the closeness implications inherent in a/one step away from to be foregrounded by means of reinforcing items, such as just and only. Another important characteristic of the analyzed expression’s grammatical attestations manifests itself in the highly confined determination and modification patterns of the largely decategorialized form step, which is only compatible with the indefinite article and emphasizers, including one, at the same time rejecting definite determiners and purely qualitative adjectives.

As suggested before, the emergence of an approximator function in the expression a/one step away from and the consequent host-class expansion to adjectives is still a nascent phenomenon, whose attestations in the scrutinized empirical material are few and far between. Future research on the topic should therefore include a larger-scale examination based on present-day English data which would make it possible to better characterize the distributional profile of a/one step away from used in the degree modifier function on the one hand, and to verify the hypothesis that the extension to adjectival elements was licensed by uses where the adjective originally appeared within a verbal gerund, itself being a complement of the copular be.

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank an anonymous reviewer and Prof. Merja Kytö for their instructive comments on a first draft of this paper. I am also grateful to my native-speaker informant for sharing with me his intuitions pertaining to some of the linguistic examples analyzed in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Damian Herda

Damian Herda is a Ph.D. candidate in Linguistics at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland. His research interests revolve around grammaticalization theory and lexical semantics.

Notes

1 Alternatively, it is possible to assume that away from constitutes a single complex preposition to start with, in which case the measure NP modifies the PP.

2 In a vast majority of cases, however, the lexical metaphorical uses exhibit a syntactic structure different from that of the spatial attestations, since in the former situation, a/one step typically does not function as a measure modifier.

3 In this respect, grammaticalization bears similarity to lexicalization, in that fixation is a characteristic feature of the latter process (cf. Himmelmann Citation2004).

4 However, since grammaticalization does not entail any ‘sudden emptying of meaning’ (Hopper & Traugott Citation2003: 95), it is expected that as an expression is grammaticalizing, ‘some traces of its original lexical meanings tend to adhere to it’, so that ‘details of its lexical history may be reflected in constraints on its grammatical distribution’ (Hopper & Traugott Citation2003: 96), a phenomenon known as persistence (cf. Hopper Citation1991).

5 For arguments in favor of the view that conceptual metaphors in general tend to have a metonymic basis, see Barcelona (Citation2000).

6 Frequently uttered combinations of forms likewise tend to be automized and hence phonetically reduced in some measure (Traugott & Trousdale Citation2013: 122), as evidenced by the form gonna < going to (Hopper & Traugott Citation2003: 3). However, the string a/one step away from does not yet seem to have been affected by an analogous reduction, the reason being that its grammaticalization is still incipient.

7 This unanalyzable attestation, cited in (i), presumably constitutes an aspectual use of step away from, the omitted complement standing for sexual activity. Thus, the utterance in question may be considered a form of auto-censure.

Cory is going on his . Isn’t that sweet? Yeah. Poor slob. What are you saying? You’re his father. You should be proud. Hey, I’ve been on the guy side of dating. I mean, he’s fine now, but he’s just a little step away from … huh-huh-huh-huh-huh. (COHA, 1994).

8 Since the COHA and the COCA belong to the same family of corpora, they share a fraction of recent material. Nonetheless, synchronic attestations also present in the diachronic data were not treated as doublets.

9 Although originally assigned to the similative category, (30) is felt to constitute an aspectual use by both the anonymous reviewer and my native-speaker informant, and thus it has been reclassified accordingly.

10 Interestingly, one may perform an analogous reinforcing function in relation to so-called small size nouns in negative polarity contexts, e.g. not to have one bit/scrap/shred of X (cf. Brems Citation2007).

11 Note, however, that (51), which is an excerpt from song lyrics, plays on the word crutch, which is why step away from may be perceived as a context-dependent degree expression here.

12 The native speaker whom I have consulted agrees with a degree modifier interpretation of (52)–(53) as well as (40), even though the anonymous reviewer considers the possibility of the pertinent examples being aspectual in nature.

References

- Barcelona, Antonio. 2000. On the plausibility of claiming a metonymic motivation for conceptual metaphor. In Antonio Barcelona (ed.), Metaphor and metonymy at the crossroads: A cognitive perspective, 31–58. Berlin and New York, NY: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad & Edward Finegan. 1999. Longman grammar of spoken and written English. London: Longman.

- Bisang, Walter & Björn Wiemer. 2004. What makes grammaticalization? An appraisal of its components and its fringes. In Bisang et al. (eds.), 3–20.

- Bisang, Walter, Nikolaus Himmelmann & Björn Wiemer (eds.). 2004. What makes grammaticalization? A look from its fringes and its components. Berlin and New York, NY: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Boye, Kasper & Peter Harder. 2012. A usage-based theory of grammatical status and grammaticalization. Language 88(1), 1–44.

- Brems, Lieselotte. 2007. The grammaticalization of small size nouns: Reconsidering frequency and analogy. Journal of English Linguistics 35(4), 293–324.

- Brinton, Laurel J. & Tohru Inoue. 2020. A far from simple matter revisited: The ongoing grammaticalization of far from. In Merja Kytö & Erik Smitterberg (eds.), Late Modern English: Novel encounters, 271–293. Amsterdam and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Brinton, Laurel J. & Elizabeth C. Traugott. 2005. Lexicalization and language change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Budts, Sara & Peter Petré. 2016. Reading the intentions of be going to: On the subjectification of future markers. Folia Linguistica 37(1), 1–32.

- Bybee, Joan. 2003. Cognitive processes in grammaticalization. In Michael Tomasello (ed.), The new psychology of language: Cognitive and functional approaches to language structure, vol. 2, 145–167. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Bybee, Joan & William Pagliuca. 1985. Cross-linguistic comparison and the development of grammatical meaning. In Jacek Fisiak (ed.), Historical semantics and historical word- formation, 59–83. Berlin and New York, NY: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Bybee, Joan, Revere Perkins & William Pagliuca. 1994. The evolution of grammar: Tense, aspect, and modality in the languages of the world. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- COCA = Davies, Mark. 2008. The Corpus of Contemporary American English. https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/ (accessed on October 26, 2021).

- COHA = Davies, Mark. 2010. The Corpus of Historical American English. https://www.english-corpora.org/coha/ (accessed on October 11, 2021).

- Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect: An introduction to the study of verbal aspect and related problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Croft, William. 2001. Radical construction grammar: Syntactic theory in typological perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Evans, Nicholas & David Wilkins. 2000. In the mind’s ear: The semantic extensions of perception verbs in Australian languages. Language 76(3), 546–592.

- Fortescue, Michael. 2010. Similitude: A conceptual category. Acta Linguistica Hafniensia 42(2), 117–142.

- Heine, Bernd. 1994. On the genesis of aspect in African Languages: The proximative. In Kevin E. Moore, David A. Peterson & Comfort Wentum (eds.), Proceedings of the twentieth annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: Special session on historical issues in African linguistics, 35–46. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

- Heine, Bernd, Ulrike Claudi & Friederike Hünnemeyer. 1991. Grammaticalization: A conceptual framework. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Himmelmann, Nikolaus. 2004. Lexicalization and grammaticization: Opposite or orthogonal? In Bisang et al. (eds.), 21–42.

- Hopper, Paul J. 1991. On some principles of grammaticization. In Elizabeth C. Traugott & Bernd Heine (eds.), Approaches to grammaticalization, vol. 1, 17–35. Amsterdam and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Hopper, Paul J. & Elizabeth C. Traugott. 2003. Grammaticalization, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kuryłowicz, Jerzy. 1965. The evolution of grammatical categories. Diogenes 51, 55–71.

- Lakoff, George & Mark Johnson. 1980. The metaphorical structure of the human conceptual system. Cognitive Science 4, 195–208.

- Langacker, Ronald. 1977. Syntactic reanalysis. In Charles N. Li (ed.), Mechanisms of syntactic change, 57–139. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Moore, Kevin E. 2014. The spatial language of time: Metaphor, metonymy, and frames of reference. Amsterdam and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Paradis, Carita. 1997. Degree modifiers of adjectives in spoken British English. Lund: Lund University Press.

- Paradis, Carita. 2008. Configurations, construals and change: Expressions of DEGREE. English Language and Linguistics 12(2), 317–343.

- Petré, Peter, Kristin Davidse & Tinne Van Rompaey. 2012. On ways of being on the way: Lexical, complex preposition and aspect marker uses. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 17(2), 229–258.

- Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech & Jan Svartvik. 1985. A comprehensive grammar of the English language. London: Longman.

- Sweetser, Eve. 1988. Grammaticalization and semantic bleaching. In Shelley Axmaker, Annie Jaisser & Hellen Singmaster (eds.), Proceedings of the fourteenth annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 389–405. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

- Traugott, Elizabeth C. 1989. On the rise of epistemic meanings in English: An example of subjectification in semantic change. Language 65(1), 31–55.

- Traugott, Elizabeth C. 2003. Constructions in grammaticalization. In Brian D. Joseph & Richard D. Janda (eds.), The handbook of historical linguistics, 624–647. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Traugott, Elizabeth C. 2008. Grammaticalization, constructions and the incremental development of language: Suggestions from the development of degree modifiers in English. In Regine Eckhart, Gerhard Jäger & Tonjes Veenstra (eds.), Variation, selection, development: Probing the evolutionary model of language change, 219–250. Berlin and New York, NY: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Traugott, Elizabeth C. 2010. (Inter)subjectivity and (inter)subjectification: A reassessment. In Kristin Davidse, Lieven Vandelanotte & Hubert Cuyckens (eds.), Subjectification, intersubjectification and grammaticalization, 29–71. Berlin and New York, NY: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Traugott, Elizabeth C. 2011. Grammaticalization and mechanisms of change. In Bernd Heine & Heiko Narrog (eds.), The Oxford handbook of grammaticalization, 19–30. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Traugott, Elizabeth C. & Richard B. Dasher. 2002. Regularity in semantic change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Traugott, Elizabeth C. & Graeme Trousdale. 2010. Gradience, gradualness and grammaticalization: How do they intersect? In Elizabeth C. Traugott & Graeme Trousdale (eds.), Gradience, gradualness and grammaticalization, 19–44. Amsterdam and Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Traugott, Elizabeth C. & Graeme Trousdale. 2013. Constructionalization and constructional changes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.