Courageous and Ethical Dialogues That Re-Search, Reenvision, and Reshape

I consider this second editorial a partner to the first, therefore, I will once again turn to bell hooks’s concept of a “love ethic” (Citation2001, p. xix) and Shawn Wilson’s (Opaskwayak Cree) concept of the relational as a grounding concept (Citation2008, p. 7). The relational can hold many dialogic forms, both textual and visual. I introduce a conversation with Diné artist Melanie Yazzie as a welcome to the authors’ manuscripts in this issue. Yazzie’s international print portfolios with Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists partner with the authors’ articles because together they create space for much-needed dialogues.

Yazzie’s print portfolios, as a counternarrative to hierarchy, along with the authors’ articles in this issue aim to “make necessary changes” (hooks, Citation2001, p. 91). Speaking of dialogue, peace builder Daisaku Ikeda observed that

courage and endurance are essential if we are to continue the painstaking work of loosening the knots of attachment that bind people to a particular point of view. The impact of this kind of humanistic diplomacy can move history in a new direction. (Ikeda, Citation2007, para. 16)

Yazzie’s art and portfolios, alongside the authors’ articles here, are just such examples of courage and endurance.

“The Print Portfolios I Curate Are Placed in Collections Which Then Brings Everybody Up”

(personal communication, Melanie Yazzie, April 2024)

The ways in which Melanie Yazzie works reframe research as a collaborative process. Her ways of thinking, feeling, believing, and knowing become an example of joyful resistance, or in her words, “a quiet revolution.” Yazzie notes, “I think of the portfolios as democratic—in that way nobody’s more important than somebody else. I do my community-building through my portfolio exchanges” (personal communication, April 2024).

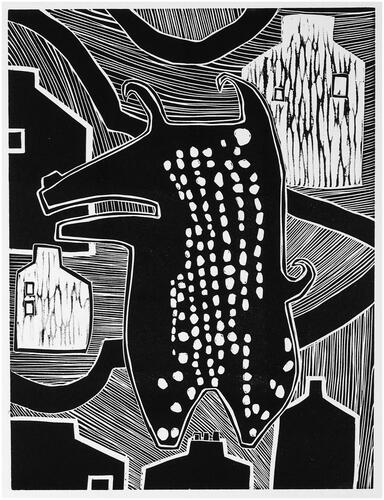

A professor of printmaking in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Colorado Boulder, Yazzie is a printmaker, painter, and sculptor. Her work draws upon her rich Diné (Navajo) cultural heritage by following the Diné dictum “walk in beauty,” of creating beauty and harmony. As an artist, she works to serve as an agent of social change by encouraging others to learn about social, cultural, and political phenomena shaping the contemporary lives of Native peoples in the United States and beyond. Her work incorporates both personal experiences as well as events and symbols from Diné culture ().

Yazzie and I met many years back at a symposium when I was a doctoral student at Teachers College, and where my mentor Graeme Sullivan had organized a Conversations Across Cultures Conference, to which Yazzie was invited as a visiting artist and speaker. Some years later, when I was an art education professor, we invited Yazzie as a visiting artist to both the Northern Illinois University printmaking and art and design education departments for an inspiring visit with our students.

Yazzie’s own artwork and life are focused on making room for many voices. Through her curation of more than 100 international print portfolios, Yazzie has honored many artists by supporting and promoting their work. She states that she began her portfolios to confront and resist the exclusionary practices in academia. Her sense of exclusion from known Native American projects, fellowships, awards, and the mistaken comments that she was a privileged minority catalyzed her creation of inclusive possibilities by curating her own print portfolios. “I thought in my Navajo way, ‘How do I look at this? How do I think it into a better place?… I could be choosing the people… nice people with a good heart” (as cited in Ballengee Morris & Staikidis, Citation2017, p. 165). Recognizing feelings of exclusion enabled her to reflect deeply on the sharing attitude toward life that has informed every aspect of her identity.

The excerpts from our ongoing, most recent dialogue communicate the importance of following individual paths, sharing, collaboration, and community building as composite aspects of Yazzie’s artistry and teaching.

MY: “The place that I create from is my own path based on my own experience. I’ve been inspired by my grandparents and their way of living and making their way in life. That’s what’s inspired the work I do and the community building.”

“With the print exchanges, I noticed that when we need to get ahead in this academic world exhibitions for visual artists are really important. So when I was putting together a project, I would seek out people who might not succeed in a competitive atmosphere. I began to curate these projects with established people as well as those just starting out. The print portfolios are placed in collections, which then brings everybody up.”

KS: “Participating in your print portfolios has been meaningful for me. How did you begin these print exchanges?”

MY: “I realized there was a hierarchy and began to question who was deciding my path. I decided I’m not going to wait to get invited, I’ll organize my own portfolios. Then I could bring people into the portfolios who were not well known. In my mind this was a quiet revolution. I realized it was important to help those who might be too shy to break through these cruel barriers. I replaced cruelty with caring. That’s been what’s guided me.”

KS: “A significant moment for me was taking part in your portfolio during COVID. Can you speak about how the idea came to you?”

MY: “Yes. The call to share our experiences during COVID was a love care package going out to all of the participating artists. Everyone could put their experiences into their prints. I wanted to give the artists hope and help them feel connected. I thought, ‘These portfolios are projects that can bring healing and support.’ When you’re actually holding the physical work that somebody has put their heart into, it sends out this powerful feeling that you’re not alone. And that’s what I wanted for that project.”

“Personally, I felt a huge sense of loss in 2020 when my mom got sick and passed on from COVID. She was a very healthy and strong person, and it was devastating. This was happening to a lot of people in Indigenous communities. These print exchanges have kept me going. Because they’re about giving back.”

“The COVID project also helped me to understand what was taking place in our communities with this illness. It was unseen and scientists were telling us what it was, but I thought, ‘Wow this is like when the illnesses that spread across Indigenous Americas killed so many people.’ A lot of those thoughts about contact and colonization came into my mind with this project, which made it all the more important to create connection between people so that people weren’t feeling despair or sadness.”

KS: “I remember opening that particular portfolio so carefully packaged in the navy-blue box. The individual artists’ voices created a community for me that felt like a family space. And the prints were so beautiful as a collective.”

“My next thought is to ask if you see these portfolios as sustaining community over time.”

MY: “I’ve done over 100 now. I see them as a support system for all participating artists. They’re my way to combat the notion of gatekeepers. Creating these portfolios is my quiet way of rebelling against how things are done. I think of it as contributing by bringing people’s work up.”

I ask Melanie if she would talk about her own creative work…

“When I was an undergraduate, I asked my mother and grandmother to draw something and they both drew little homes. After my mother’s death, during COVID, I was just moved to take older prints of mine and cut them up to make collages of houses. These collages made me feel connected to my mom and my grandmother. I just keep making them; they’re 4-inch by 6-inch pieces of paper, and I’m up to over 1,000. When the Marshall fire in Boulder happened, with over 1,000 houses that got burned down, I thought ‘I’m making houses that are tiny prayer flags for the world. I’m sending healing messages through the houses.’ That’s why I make my art: It’s about feeding my soul and it helps me see the world in a more positive way.”

“When I was in grad school I made work about the reality of the history of our people. But these days, I make work that is positive and wonderful with animals and bright colors, which heals me and brings me joy. People see this work as playful. Yet, as part of this process, when I have an artist talk, I’m able to speak about the boarding school experiences. I’m able to speak about Native women who have been sterilized without knowing it. I also use mapping in my work to speak about land-based issues. There are elements of our histories that are always in the work. I can unpack different parts of the story and educate my audience. That’s what drives me to make the work. I’m thinking of my own healing. But, also my own way of educating people and helping them understand” (personal communication, Melanie Yazzie, April 2024).

Melanie Yazzie holds bold dialogues with viewers, fellow artists, students, and scholars. Thank you to Melanie for holding this conversation with me and with all of you as well. It has been a great gift.

Listening as a Bridge to Action: Bringing Everybody Up

Like Yazzie, the authors in Studies in Art Education 65(2) listen in pursuit of dialogue that engenders socially conscious action that can “bring everybody up.”

As an example of listening, bold dialogue with the field, and courageous action in response, this issue of Studies begins with Kevin Jenkins’s exploration of DIY online community spaces as pathways of entry into trans youth and adult lives. Jenkins uses an autoethnographic methodology—in my view, not common enough in art education—as an important tool of inquiry to support relational learning. Jenkins’s is well-done autoethnographic research, connecting personal and social contexts. His research and writing become a site of witness for his trans journey and provide an emic perspective that informs readers about what trans youth and nonbinary students have lived through. Jenkins rightfully asks how anti-trans legislation might alter art classrooms across the country today when trans and nonbinary students and teachers are courageously becoming more visible. He honestly asks much-needed questions, stating that “these inquiries are at the center of relational learning, creating, and doing with others—tenets significant for the future of democratic life, art, and art education practices.” Bravo.

James O’Donnell’s article, whose partial title is “What Is the Truth?,” forms a bridge with Jenkins’s piece. Both speak to the need to hold critical dialogues with students, art educators, and future educators to reshape the field to create a critically conscious citizenry. O’Donnell writes, “This all starts with listening to our students and empowering them to express themselves because the courses of their lives will increasingly be shaped by what happens online.” The author’s mixed-methods study listens to what students reveal through a quantitative survey on critical media literacy followed by arts-based components and assessment. Artmaking leads students to a growing self-awareness about the negative impact of their relationship with online media. The author wants to make sure that at all education levels, critical media literacy becomes an active part of the art education curriculum. O’Donnell, like Jenkins, brings the research home to the art education field.

Joy G. Bertling, Tara C. Moore, and Lauren Farkas share longitudinal research based on a continuing commitment to courageous dialogues about a “world of accelerating ecological devastation.” In this iteration, the research takes the form of a qualitative multiple case study involving three art educators across the United States who demonstrate high levels of ecological integration in their preservice art education curricula and pedagogy. Like Jenkins and O’Donnell, Bertling et al. listen first, in this case, to the Earth. In confronting the reality of the Anthropocene as a pivotal concept, the authors relocate the Earth as the center of consciousness. They create research whose findings hold the potential to reenvision and reshape the field through integrating environmental approaches to teaching in art teacher education to effect change. Longitudinal work such as theirs is rare in art education, and like Jenkins’s autoethnography, much needed. As the authors note, their art teacher research participants have “stay[ed] with the trouble” (Haraway, Citation2016, p. 3) as have the authors. They call art education to action: “We hope this study will serve as a compelling provocation for ecological reenvisionings of programs and opening illustration of the kind of shifts that will be necessary.”

As hooks (Citation2001) observes, “We can collectively regain our faith in the transformative power of love by cultivating courage, the strength to stand up for what we believe in, to be accountable both in word and deed” (p. 92). Jenkins, O’Donnell, and Bertling et al. have not only addressed issues through courageous dialogues, but also through insisting that action be taken to catalyze important change. Continuing, Christine Montecillo Leider, Johanna M. Tigert, Nasiba Norova, Golnar Fotouhi, Julie Sawyer, and Rachel Tianxuan Wang convince through their quantitative study that multilingual learners (MLs) deserve equitable access to arts education, finding that the arts are critical for MLs. The authors observe, “We take the stance that the arts are crucial for the development of an informed, humane citizenry, and that MLs should be equitably entitled to such development.” Again, through listening, researchers examine teachers’ beliefs and practices to provide recommendations about the ways art teacher education can change to ensure the pedagogical needs of multilingual learners.

Beth Link examines the “White habitus” in art education and demonstrates through her case study that when art educators re-search their teaching practices through intentional bold dialogues, antiracist change can take place. In this qualitative ethnographic research inquiry, Link listens to what the two teacher participants say they do, yet helps them see what they actually do. This research constructs space for dialogues to support participants to reconsider their entrenched perspectives and positions relative to race and racial stereotyping. Through listening to and observing participants, Link enables them to begin to tackle their own givens and assumptions. Their resulting teaching practices start to become counternarratives to perpetuating the White habitus in art education. Underlying Link’s research is the author’s belief that “individual teachers have agency to modify or subvert the curriculum through their enactment.” Link connects such a reenvisioning of practice with a potential reshaping of the field.

In their important manuscript, M. Sylvia Weintraub and Andrés Peralta, like Kevin Jenkins, think with the reader about the impact of DIY spaces in and for art education. The authors’ attention to online sites as dynamic spaces illustrates possibilities through which self-directed learning can positively influence the field. In their mixed-methods study, authors examine emergent platforms such as TikTok, YouTube, and Pinterest to discuss the potential of collaborative learning spaces as catalysts for curricular development in formal art education settings. This work listens to the needs of art learners through observing what they actually do, thereby coming to understand what youth cultures actually need. Beginning with a learner-centered curriculum basing research on learner intention and process disrupts a teacher-as-expert model. As Weintraub and Peralta note, “Social media’s participatory nature generates collective learning and knowledge production, an engagement with difference, and a diversity of thought that challenges traditional hierarchies aligning with critical pedagogy.”

Acts of Listening That Move Art Education Into New Spaces

A thematic thread tying together author submissions in this issue came to me when I first read the commentaries. Commentary Editor Tyson Lewis has envisioned commentaries across disciplines in a call-and-response that is truly exciting. In the first commentary, Tran Nguyen Templeton asks that as adults we notice (listen), yet simultaneously “resist reading” and interpreting young children’s artmaking processes. Templeton suggests we learn how to make space for the child in ways that “might take us somewhere new, to other ways of seeing… in ways that are beyond our perception.” In his response to Templeton, Christopher M. Schulte moves us, as adults, into a new space, in which we engage with a “reconsideration of [our] attitudes and values,” which “flatten” children’s actions. Schulte observes, “The way through this problem is not to compel new strategies that will somehow make it all knowable” but instead “to accept earnestly the work of listening, of being attuned, and the uneasy, albeit generative, possibilities of leaning into doubt.” In her media review of Drawing Deportation: Art and Resistance Among Immigrant Children (Rodriguez Vega, Citation2023), Hayon Park, like Templeton and Schulte, requests that as adults who look at children’s art we “attempt to practice the relational act of listening… to listen empathetically, to be keen on their lived experiences.” Drawing more parallels, in the media review by Sue Uhlig, the author notes that editors of Visual Participatory Arts Based Research in the City (Trafí-Prats & Castro-Varela, Citation2022) listened to the “spaces within cities… as sites of solidarity and care through the potentialities of art.” Ideas of solidarity and care circle back to artist Melanie Yazzie, whose art and print portfolios lend both solidarity and care through providing collective spaces of sharing. Authors urge their audience to immerse themselves in the act of listening and dialoguing with self, with others, and with our worlds. Their research inquiries, based on listening, create serious spaces to hold bold dialogues, which result in taking action in the way that hooks (Citation2001) spoke of a “love ethic” (p. xix).

As Media Review Editor David Herman Jr. observes, “Our experiences and histories, far from being linear or isolated, intertwine to form complex involvements that shape our identities and interactions with the world.” From my perspective, such complex involvements require that we interact to create spaces for all. hooks (Citation2001) encouraged her readers, “To begin by always thinking of love as an action rather than a feeling [as] one way in which anyone using the word in this manner automatically assumes accountability and responsibility.” And this accountability and responsibility necessitates bold dialogues to ensure equity. Mutually respectful dialogue is not always easy. Melanie Yazzie and the authors in this issue base themselves on a desire to move art and art education forward through listening, dialogue, action. Dialogue in this sense precipitates action. Paolo Freire (Freire & Macedo, Citation1995) articulated this so beautifully when he said,

Dialogue is a way of knowing and should never be viewed as a mere tactic to involve students in a particular task. We have to make this point very clear. I engage in dialogue not necessarily because I like the other person. I engage in dialogue because I recognize the social and not merely the individualistic character of the process of knowing. In this sense, dialogue presents itself as an indispensable component of the process of both learning and knowing. (p. 379)

As a closing thought, the six manuscripts in Studies 65(2) insist that as art educators we pay close attention to what takes place in our preservice art education programs. Therefore, although the research inquiries in Studies 65(2) speak to research in higher education, they also become sites of research for preK–12 classroom teaching. The research, in its conclusions across the authors’ pieces, makes it clear that we need to raise the critical awareness of future art teachers in our higher education programs. Through their dialogues, authors clearly recognize “the social character of the process of knowing” (Freire & Macedo, Citation1995), and such a recognition insists on the re-searching, reenvisioning, and reshaping of the art education field.

Author Note

Thank you to Christine Ballengee Morris (Cherokee Ancestry) for her review and insightful feedback of this editorial.

Acknowledgments

This time instead of a thank-you, my acknowledgment comes in the form of an apology. I apologize for the omission of tribal affiliations that occurred due to an oversight on my part in my first editorial in Studies in Art Education 65(1): “An Ethics of Care in Art Education” (Staikidis, Citation2024). In revising the editorial for publication, I removed a section at the beginning of the editorial, which included the first mention of Shawn Wilson (Opaskwayak Cree) and Emerging Elder Joseph Naytowhow (Nehihaw). Once this section was removed, their names were later cited without their tribal affiliations. I also neglected to acknowledge and thank three founders of the Indigenous Inquiry Circle (IIC)—Emerging Elder Joseph Naytowhow, Jamie Singson (Waqui/Filipino), and Patrick Lewis. They each read a draft of the editorial to see if I presented information about the IIC correctly. Thank you.

References

- Ballengee Morris, C., & Staikidis, K. (2017). Transforming our practices: Indigenous art, pedagogies, and philosophies. National Art Education Association.

- Freire, P., & Macedo, D. P. (1995). A dialogue: Culture, language, and race. Harvard Educational Review, 65(3), 377–403. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.65.3.12g1923330p1xhj8

- Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

- hooks, b. (2001). All about love: New visions. Harper Perennial.

- Ikeda, D. (2007, January 11). Moving beyond the use of military force. The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2007/01/11/commentary/world-commentary/moving-beyond-the-use-of-military-force

- Rodriguez Vega, S. (2023). Drawing deportation: Art and resistance among immigrant children. New York University Press.

- Staikidis, K. (2024). An ethics of care in art education [Editorial]. Studies in Art Education, 65(1), 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2024.2320042

- Trafí-Prats, L., & Castro-Varela, A. (Eds.). (2022). Visual participatory arts based research in the city: Ontology, aesthetics and ethics. Routledge.

- Wilson, S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood.